Trophic Duality: Taxonomic Segregation and Convergence in Prey Functional Traits Driving the Coexistence of Apex Predators

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

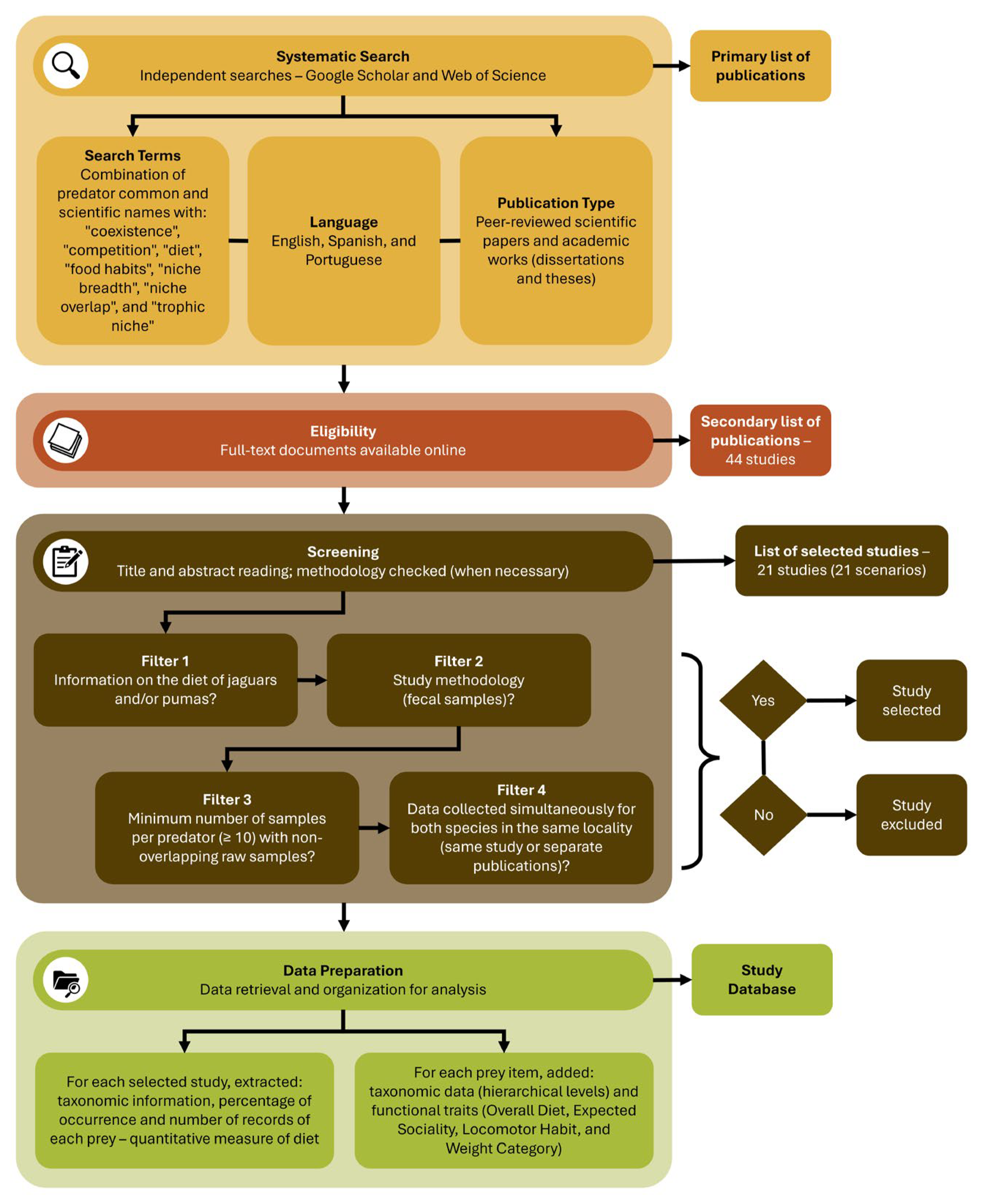

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Prey Classification and Data Treatment

2.2.2. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

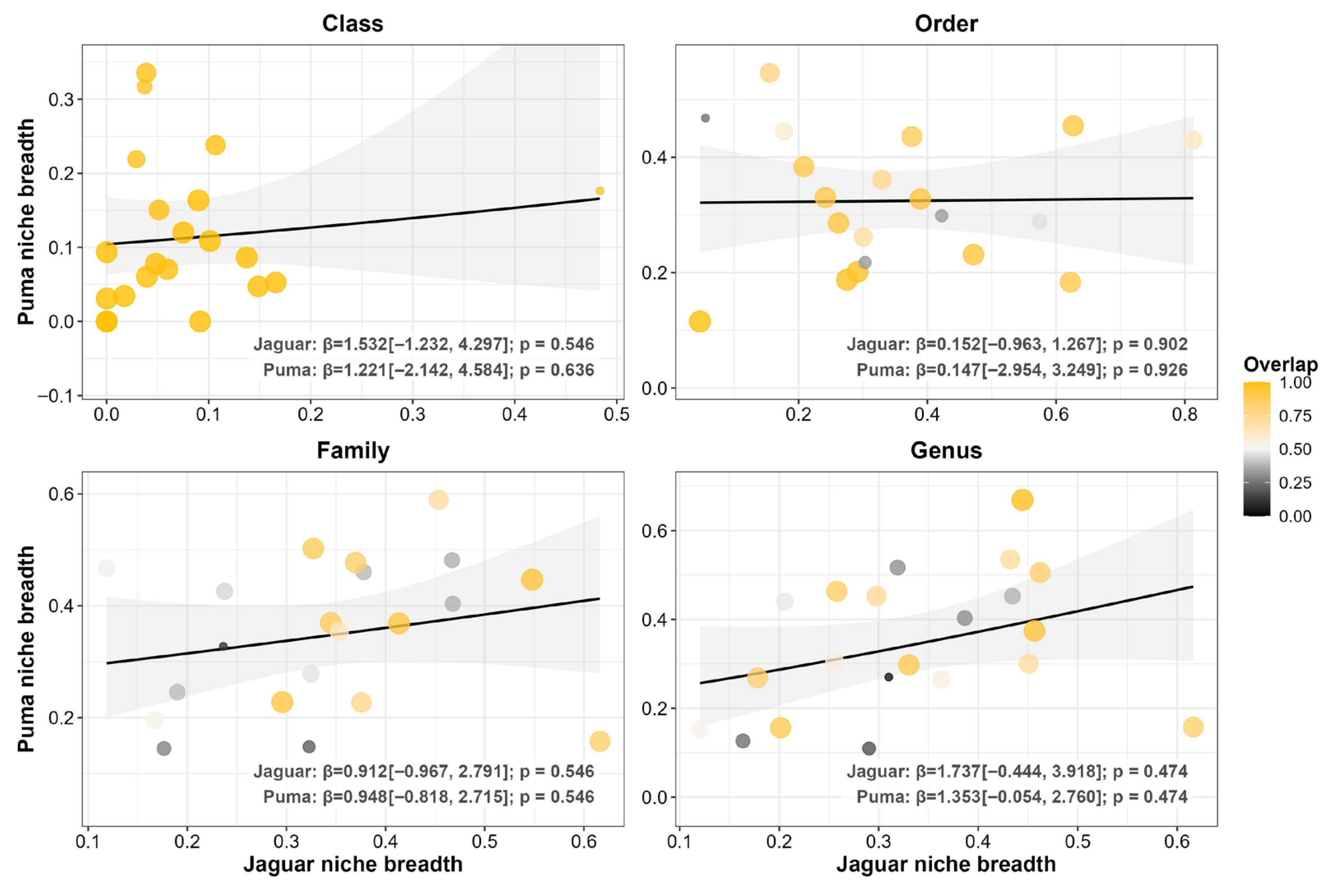

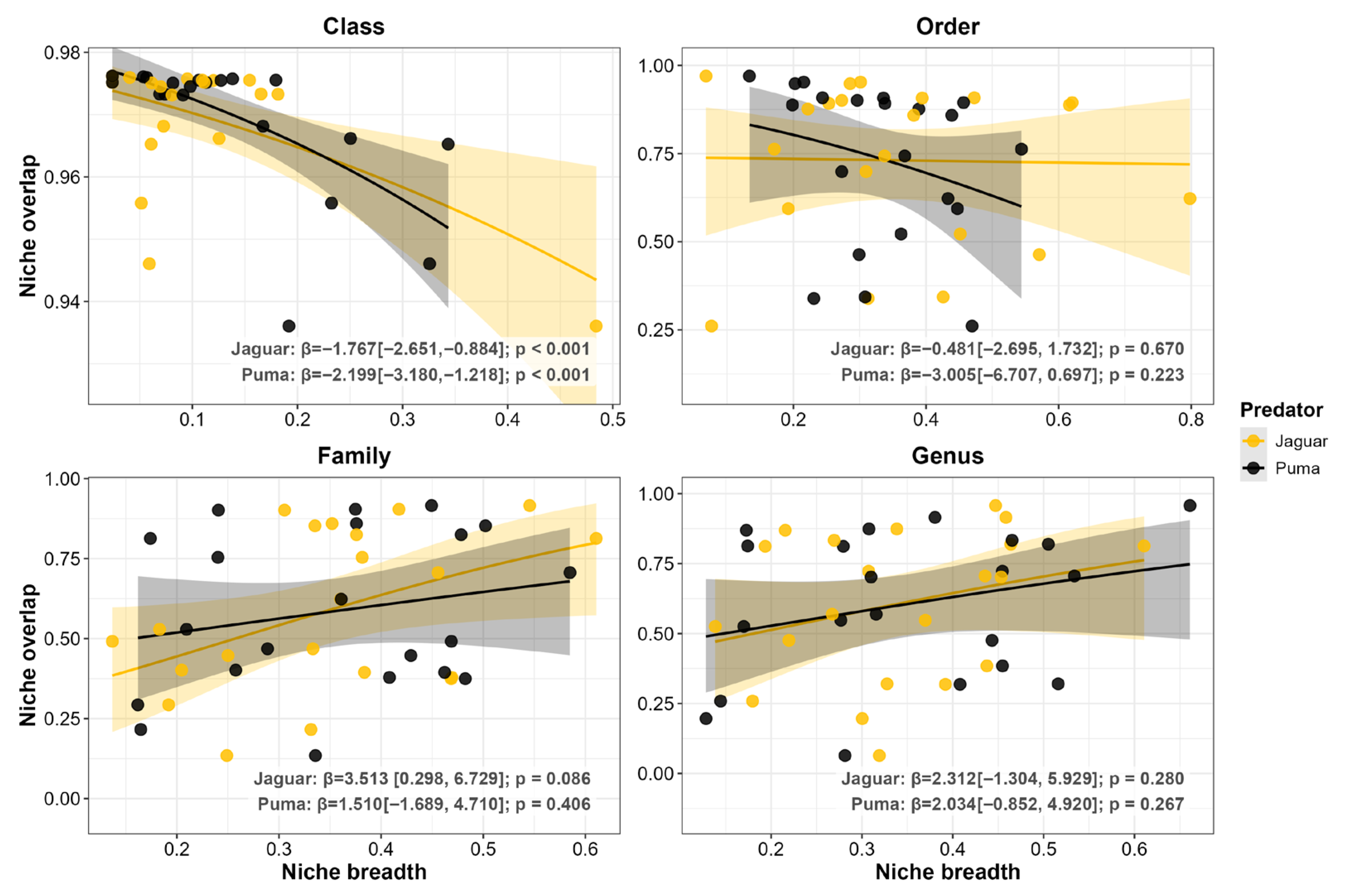

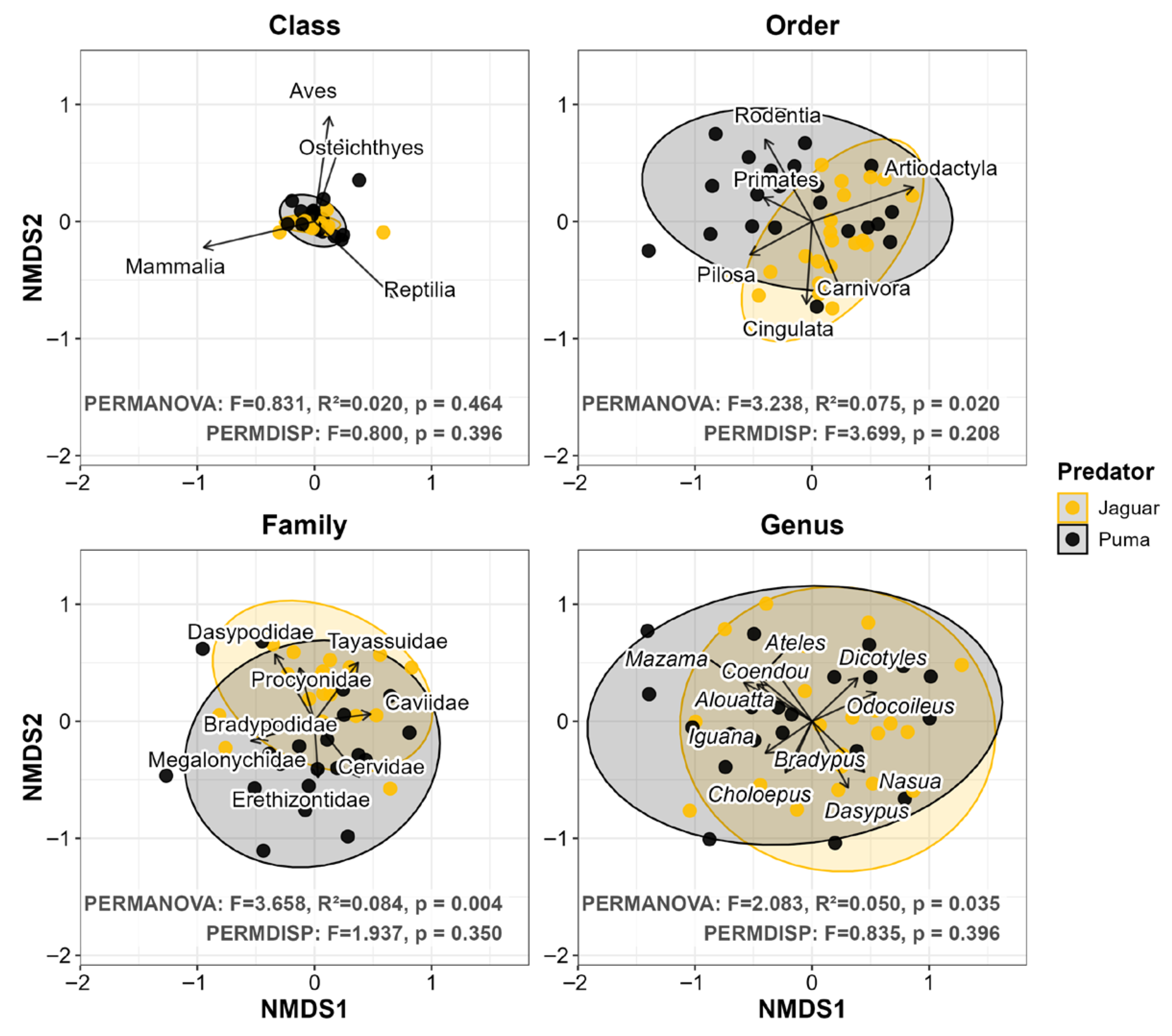

3.1. Taxonomic Patterns of Prey

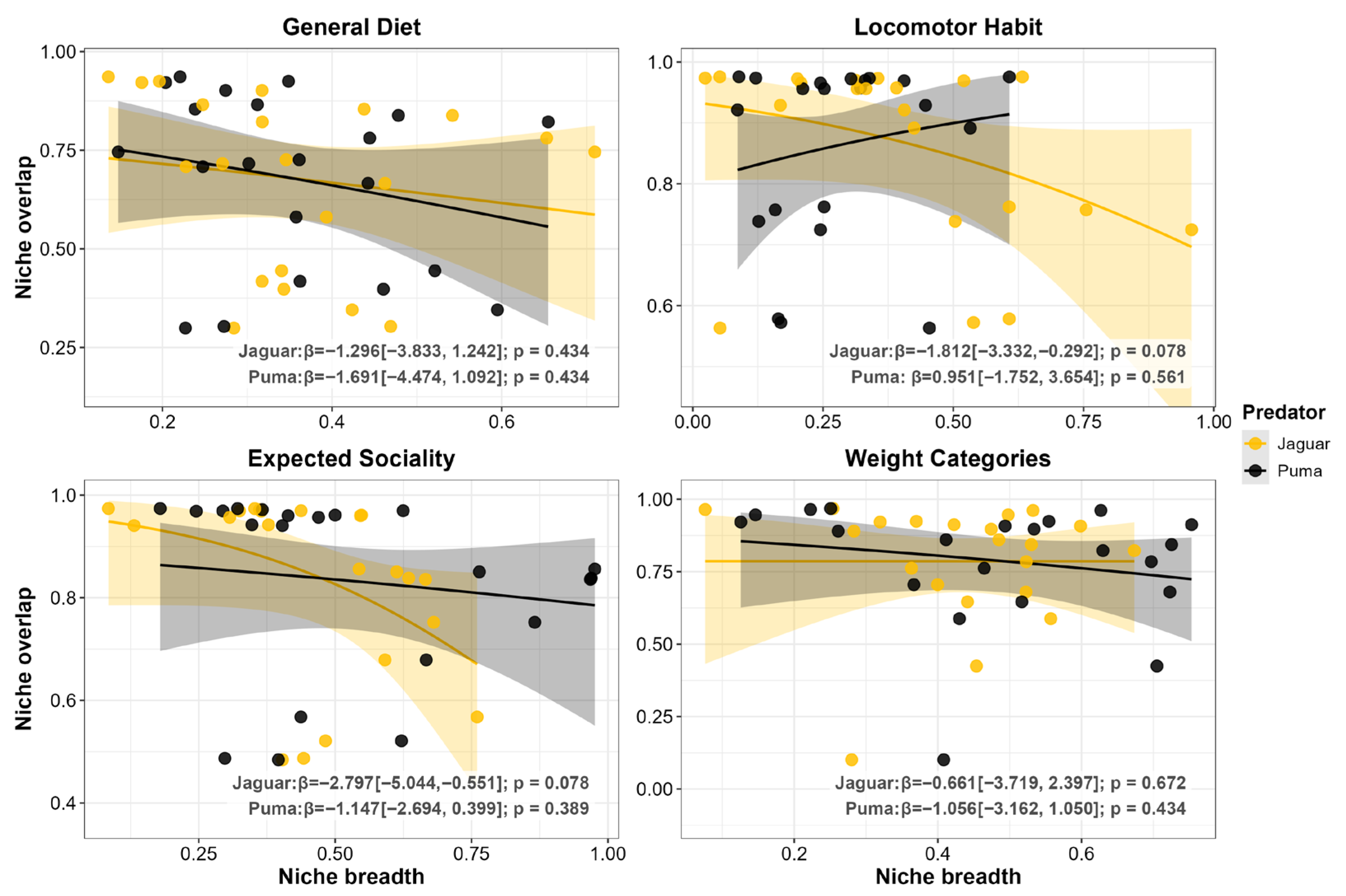

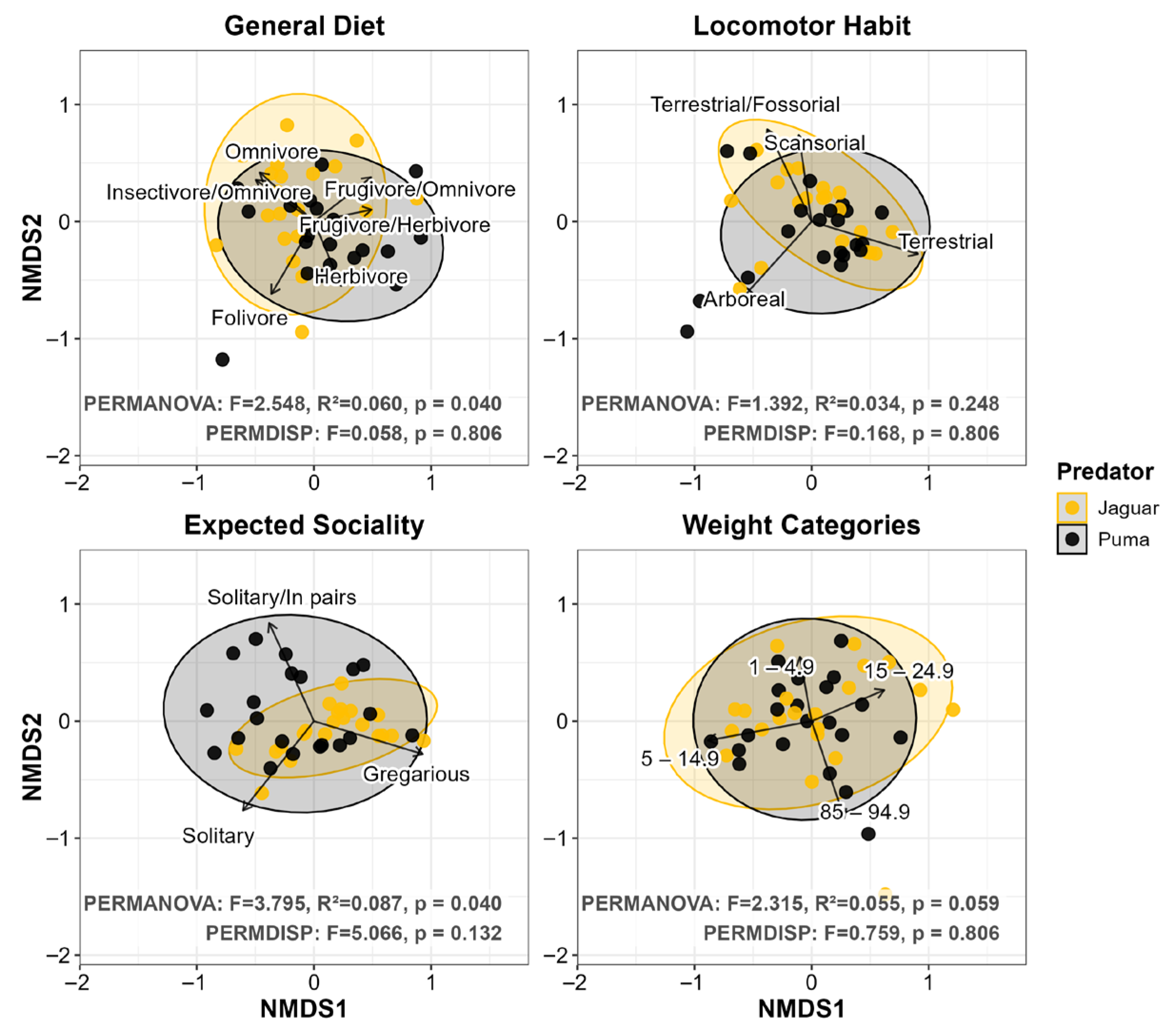

3.2. Prey Functional Traits

4. Discussion

4.1. Taxonomic Segregation: A Predominantly Stabilizing Force in Coexistence

4.2. Functional Convergence: Patterns Consistent with an Equalizing Effect on Coexistence

4.3. From Coexistence Mechanisms to Conservation Actions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMDS | Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| PERMDISP | Permutational Analysis of Multivariate Dispersion |

References

- Gause, G.F. The Struggle for Existence; Williams & Wilkins Company: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Chesson, P. Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, R.; Levins, R. The limiting similarity, convergence, and divergence of coexisting species. Am. Nat. 1967, 101, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, J.M.; Leibold, M.A. Ecological Niches: Linking Classical and Contemporary Approaches; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, G.E. Concluding remarks. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1957, 22, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoener, T.W. Resource partitioning in ecological communities. Science 1974, 185, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pianka, E.R. Niche overlap and diffuse competition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 2141–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, P.B.; HilleRisLambers, J.; Levine, J.M. A niche for neutrality. Ecol. Lett. 2007, 10, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terborgh, J.; Estes, J.A. Trophic Cascades: Predators, Prey, and the Changing Dynamics of Nature; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, J.A.; Terborgh, J.; Brashares, J.S.; Power, M.E.; Berger, J.; Bond, W.J.; Carpenter, S.R.; Essington, T.E.; Holt, R.D.; Jackson, J.B.C.; et al. Trophic downgrading of planet Earth. Science 2011, 333, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Estes, J.A.; Beschta, R.L.; Wilmers, C.C.; Ritchie, E.G.; Hebblewhite, M.; Berger, J.; Elmhagen, B.; Letnic, M.; Nelson, M.P.; et al. Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science 2014, 343, 1241484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, F.G.; Du Toit, J.T. Large predators and their prey in a southern African savanna: A predator’s size determines its prey size range. J. Anim. Ecol. 2004, 73, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, C.; Teacher, A.; Rowcliffe, J.M. The Costs of Carnivory. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durant, S.M. Competition refuges and coexistence: An example from Serengeti carnivores. J. Anim. Ecol. 1998, 67, 370–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares, F.; Caro, T.M. Interspecific killing among mammalian carnivores. Am. Nat. 1999, 153, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donadio, E.; Buskirk, S.W. Diet, morphology, and interspecific killing in Carnivora. Am. Nat. 2006, 167, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, E.G.; Johnson, C.N. Predator interactions, mesopredator release and biodiversity conservation. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 982–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanak, A.T.; Gompper, M.E. Dietary niche separation between sympatric free-ranging domestic dogs and Indian foxes in central India. J. Mammal. 2009, 90, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.; Thompson, D.; Kelly, M.; Lopez-Gonzalez, C.A. Puma concolor (Errata Version Published in 2016). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: E.T18868A97216466. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/18868/97216466 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Quigley, H.; Foster, R.; Petracca, L.; Payan, E.; Salom, R.; Harmsen, B. Panthera onca (Errata Version Published in 2018). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: E.T15953A123791436. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/15953/123791436 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Seymour, K.L. Panthera onca. Mamm. Species 1989, 340, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, M.J.P. Felis concolor. Mamm. Species 1983, 200, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broggi, P.; Teixeira, A. Felinos: A Luta Pela Sobrevivência/Wild Cats: The Struggle for Survival; Abook Publishing: São Paulo, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Monterroso, P.; Díaz-Ruiz, F.; Lukacs, P.M.; Alves, P.C.; Ferreras, P. Ecological traits and the spatial structure of competitive coexistence among carnivores. Ecology 2020, 101, e03059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, F.; Lovari, S.; Lucherini, M.; Hayward, M.W.; Stephens, P.A. Continent-wide differences in diet breadth of large terrestrial carnivores: The effect of large prey and competitors. Mammal Rev. 2024, 54, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Rosas, O.C.; Bender, L.C.; Valdez, R. Jaguar and puma predation on cattle calves in northeastern Sonora, Mexico. Rangeland Ecol. Manag. 2008, 61, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-SaintMartín, A.D.; Rosas-Rosas, O.C.; Palacio-Núñez, J.; Tarango-Arambula, L.A.; Clemente-Sánchez, F.; Hoogesteijn, A.L. Food habits of jaguar and puma in a protected area and adjacent fragmented landscape of northeastern Mexico. Nat. Areas J. 2015, 35, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, P.; Mendoza, G.D.; Martínez, D.; Rosas-Rosas, O.C. Determination of the jaguar (Panthera onca) and puma (Puma concolor) diet in a tropical forest in San Luis Potosí, Mexico. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2013, 41, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, R.; Miller, B.; Lindzey, F. Food habits of jaguars and pumas in Jalisco, Mexico. J. Zool. 2000, 252, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ortiz, Y.; Monroy-Vilchis, O. Feeding ecology of puma (Puma concolor) in Mexican montane forests with comments about jaguar (Panthera onca). Wildl. Biol. 2013, 19, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ortiz, Y.; Monroy-Vilchis, O.; Mendoza-Martínez, G.D. Feeding interactions in an assemblage of terrestrial carnivores in central Mexico. Zool. Stud. 2015, 54, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña-Covarrubias, E.; Chávez, C.; Chapman, M.A.; Morales, M.; Elizalde-Arellano, C.; Doncaster, C.P. Ecology of large felids and their prey in small reserves of the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. J. Mammal. 2023, 104, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, M.; Sánchez-Cordero, V. Prey spectra of jaguar (Panthera onca) and puma (Puma concolor) in tropical forests of Mexico. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna Environ. 1996, 31, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shedden-González, A.; Solórzano-García, B.; White, J.M.; Gillingham, P.K.; Korstjens, A.H. Drivers of jaguar (Panthera onca) and puma (Puma concolor) predation on endangered primates within a transformed landscape in southern Mexico. Biotropica 2023, 55, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novack, A.J.; Main, M.B.; Sunquist, M.E.; Labisky, R.F. Foraging ecology of jaguar (Panthera onca) and puma (Puma concolor) in hunted and non-hunted sites within the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Guatemala. J. Zool. 2005, 267, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.J.; Harmsen, B.J.; Valdes, B.; Pomilla, C.; Doncaster, C.P. Food habits of sympatric jaguars and pumas across a gradient of human disturbance. J. Zool. 2010, 280, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scognamillo, D.; Maxit, I.E.; Sunquist, M.; Polisar, J. Coexistence of jaguar (Panthera onca) and puma (Puma concolor) in a mosaic landscape in the Venezuelan llanos. J. Zool. 2003, 259, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchilla, F.A. La dieta del jaguar (Panthera onca), el puma (Felis concolor) y el manigordo (Felis pardalis) en el Parque Nacional Corcovado, Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 1997, 45, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, D.M.D. Dieta e relação de abundância de Panthera onca e Puma concolor com suas espécies-presa na Amazônia Central. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA), Manaus, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, B. Ecologia alimentar da onça-parda (Puma concolor) na Mata Atlântica de Linhares, Espírito Santo, Brasil. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Garla, R.C.; Setz, E.Z.; Gobbi, N. Jaguar (Panthera onca) food habits in Atlantic Rain Forest of southeastern Brazil. Biotropica 2001, 33, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renata, P.; Leite, M.; Galvao, F. El jaguar, el puma y el hombre en tres áreas protegidas del bosque atlántico costero de Paraná, Brasil. In El jaguar en el nuevo milenio; Medellín, R.A., Equihua, C., Chetkiewicz, C.L.B., Crawshaw, P.G., Jr., Rabinowitz, A., Redford, K.H., Robinson, J.G., Sanderson, E., Taber, A.B., Eds.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Wildlife Conservation Society/Fondo de Cultura Económica: México City, Mexico, 2002; pp. 237–251. [Google Scholar]

- De Azevedo, F.C.C. Food habits and livestock depredation of sympatric jaguars and pumas in the Iguaçu National Park area, south Brazil. Biotropica 2008, 40, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Turdera, C.; Ayala, G.; Viscarra, M.; Wallace, R. Comparison of big cat food habits in the Amazon piedmont forest in two Bolivian protected areas. Therya 2021, 12, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, A.B.; Novaro, A.J.; Neris, N.; Colman, F.H. The food habits of sympatric jaguar and puma in the Paraguayan Chaco. Biotropica 1997, 29, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuercher, G.L.; Owen, R.D.; Torres, J.; Gipson, P.S. Mechanisms of coexistence in a diverse Neotropical mammalian carnivore community. J. Mammal. 2022, 103, 618–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF. Global Biodiversity Information Facility. 2025. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- IUCN. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2025. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/en (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Pianka, E.R. The structure of lizard communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, S.H. The measurement of niche overlap and some relatives. Ecology 1978, 59, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribari-Neto, F.; Zeileis, A. Beta regression in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 34, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA). In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Balakrishnan, N., Colton, T., Everitt, B., Piegorsch, W., Ruggeri, F., Teugels, J.L., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Package ‘vegan’. Community Ecology Package, Version 2.7-2. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Forbes, R.E.; Everatt, K.T.; Spong, G.; Kerley, G.I. Diet responses of two apex carnivores (lions and leopards) to wild prey depletion and livestock availability. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 292, 110542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, B.P.; Kindlmann, P. Interactions between Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris) and leopard (Panthera pardus): Implications for their conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 2075–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karandikar, H.; Serota, M.W.; Sherman, W.C.; Green, J.R.; Verta, G.; Kremen, C.; Middleton, A.D. Dietary patterns of a versatile large carnivore, the puma (Puma concolor). Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, J.W.; Binder, W.J.; Anton, C.B.; Meyer, C.J.; Metz, M.C.; Smith, B.J.; Ruth, T.K.; Murphy, K.M.; Bump, J.K.; Smith, D.W.; et al. Prey size mediates interference competition and predation dynamics in a large carnivore community. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanak, A.T.; Fortin, D.; Thaker, M.; Ogden, M.; Owen, C.; Greatwood, S.; Slotow, R. Moving to stay in place: Behavioral mechanisms for coexistence of African large carnivores. Ecology 2013, 94, 2619–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, J.S. Functional redundancy in ecology and conservation. Oikos 2002, 98, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheel, D. Profitability, encounter rates, and prey choice of African lions. Behav. Ecol. 1993, 4, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prugh, L.R.; Stoner, C.J.; Epps, C.W.; Bean, W.T.; Ripple, W.J.; Laliberte, A.S.; Brashares, J.S. The rise of the mesopredator. Bioscience 2009, 59, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergio, F.; Caro, T.; Brown, D.; Clucas, B.; Hunter, J.; Ketchum, J.; McHugh, K.; Hiraldo, F. Top predators as conservation tools: Ecological rationale, assumptions, and efficacy. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Entringer, H., Jr.; Srbek-Araujo, A.C. Trophic Duality: Taxonomic Segregation and Convergence in Prey Functional Traits Driving the Coexistence of Apex Predators. Biology 2026, 15, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010031

Entringer H Jr., Srbek-Araujo AC. Trophic Duality: Taxonomic Segregation and Convergence in Prey Functional Traits Driving the Coexistence of Apex Predators. Biology. 2026; 15(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleEntringer, Hilton, Jr., and Ana Carolina Srbek-Araujo. 2026. "Trophic Duality: Taxonomic Segregation and Convergence in Prey Functional Traits Driving the Coexistence of Apex Predators" Biology 15, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010031

APA StyleEntringer, H., Jr., & Srbek-Araujo, A. C. (2026). Trophic Duality: Taxonomic Segregation and Convergence in Prey Functional Traits Driving the Coexistence of Apex Predators. Biology, 15(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010031