Enhancing Pollinator Support: Plant–Pollinator Dynamics Between Salvia yangii and Anthidium Bees in Anthropogenic Landscapes

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.1.1. The Urban Area

2.1.2. The Rural Area

2.2. The Plant Species

2.2.1. Visual Display and Flower Morphology

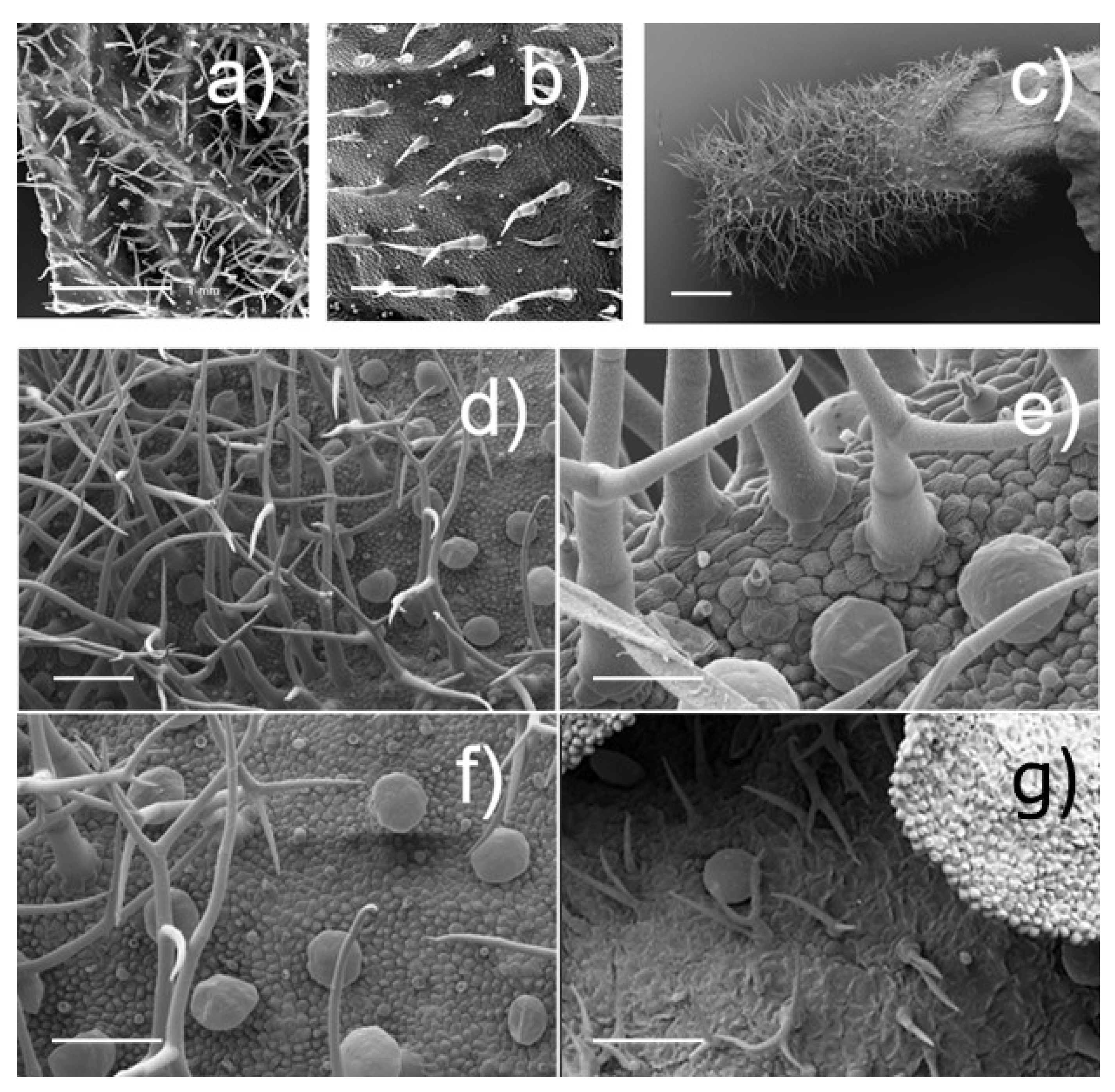

2.2.2. Trichome Analyses

2.3. Bee Records

2.3.1. Bees at the Urban Area

2.3.2. Bees at the Rural Area

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

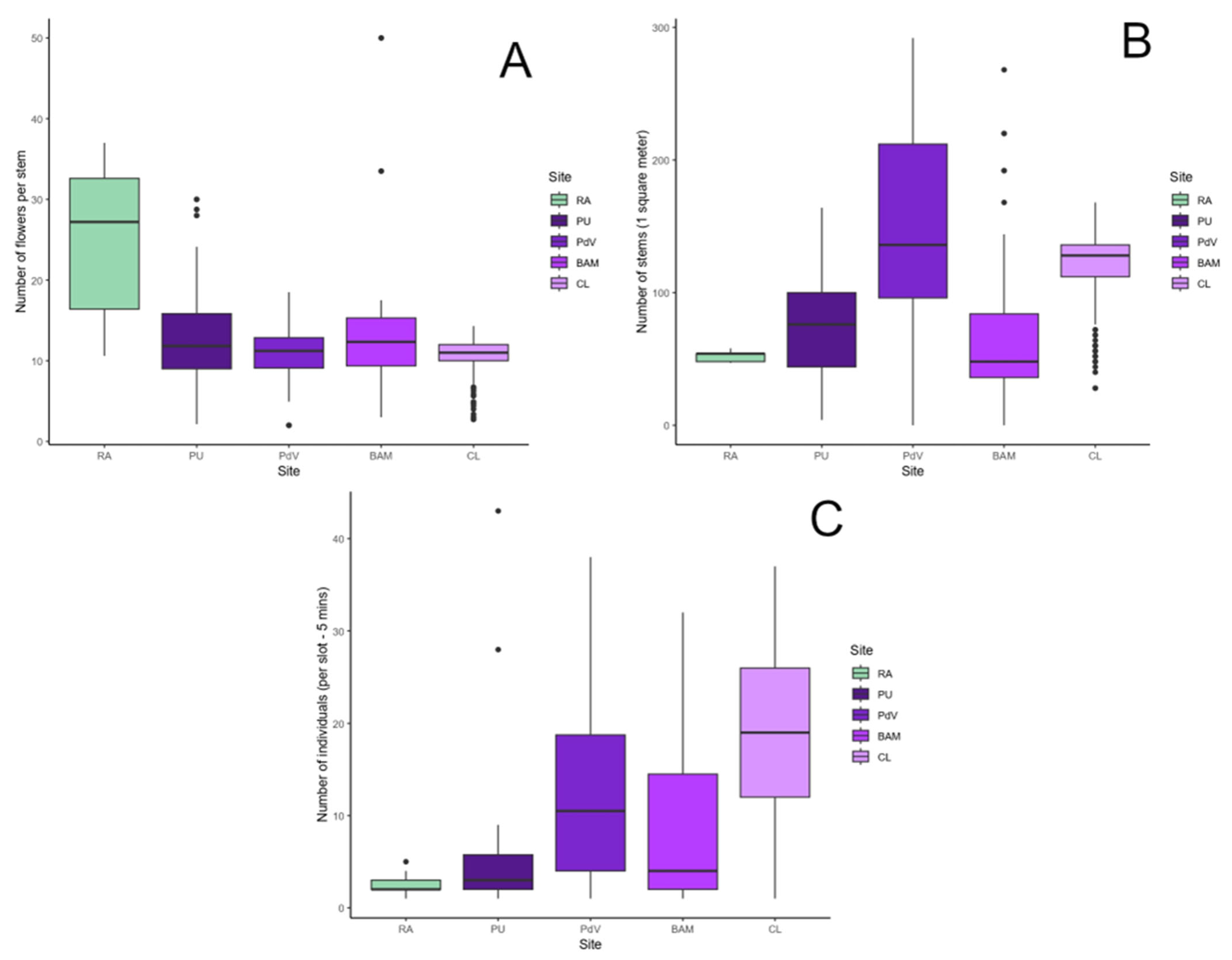

3.1. The Plant Species

3.1.1. Visual Display and Flower Morphology

3.1.2. Trichome Analyses

3.2. Bee Records

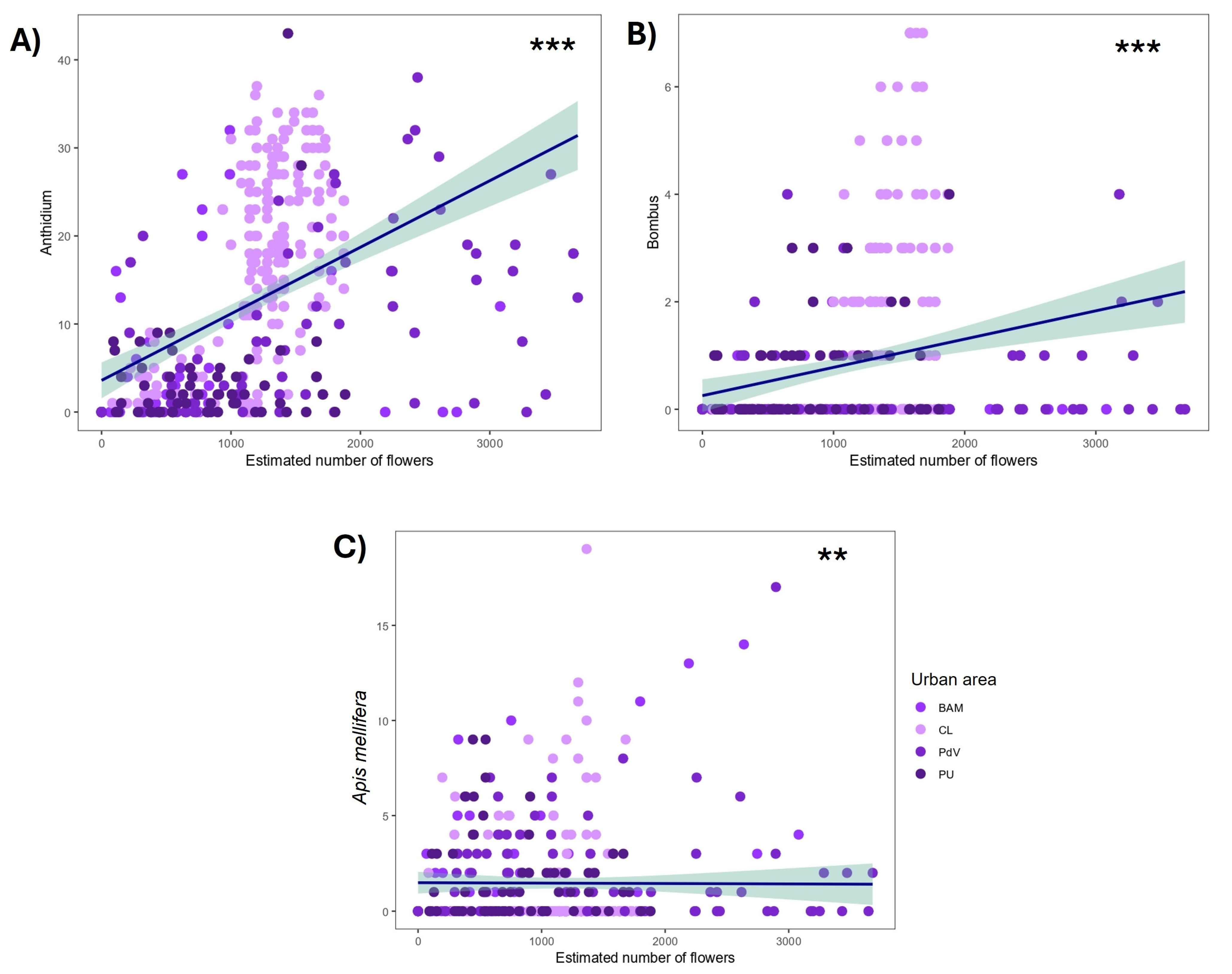

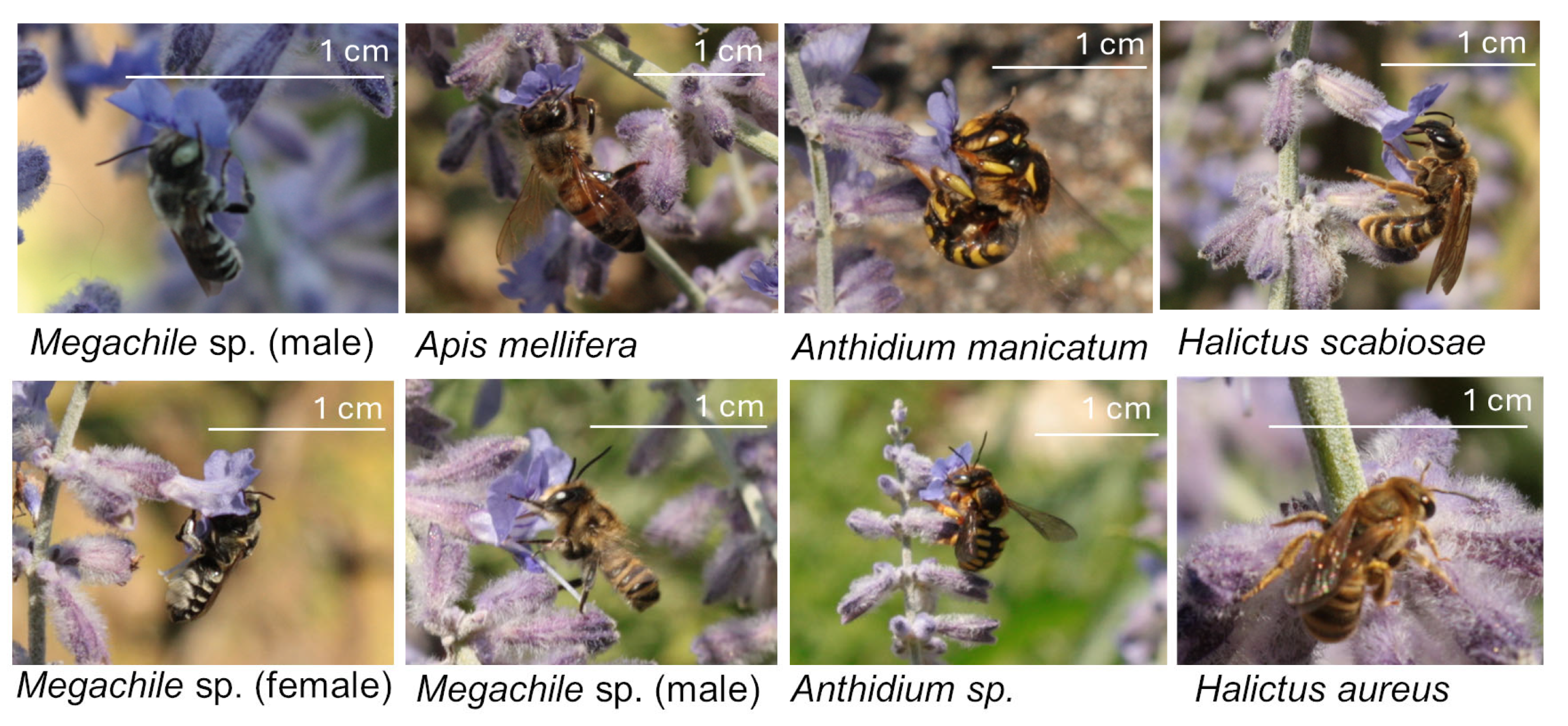

3.2.1. Bee Records at the Urban Area

3.2.2. Bee Records at the Rural Area

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Negative (−): none of the observed trichomes or ducts showed the presence of the targeted substances, which the test was designed to detect;

- Faintly positive (±): up to 10 trichomes and up to 10 ducts displayed a weak or moderate positive reaction of the secreted materials (in terms of both colour intensity and extent), implying that a low level of the targeted substances was present;

- Positive (+): 11–20 trichomes and 11–20 ducts showed the presence of the targeted substances in the form of multiple small droplets or as a single large cluster in the subcuticular spaces and within the lumen, respectively;

- Intensely positive (++): 21–30 trichomes and 21–30 ducts exhibited a very strong and clear reaction of the secreted materials, indicating the presence and high concentration of the targeted substances in the form of multiple small droplets or as a single large cluster.

References

- Fortel, L.; Henry, M.; Guilbaud, L.; Guirao, A.L.; Kuhlmann, M.; Mouret, H.; Rollin, O.; Vaissiere, B.E. Decreasing abundance, increasing diversity and changing structure of the wild bee community (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) along an urbanisation gradient. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldock, K.C.R.; Goddard, M.A.; Hicks, D.M.; Kunin, W.E.; Mitschunas, N.; Osgathorpe, L.M.; Potts, S.G.; Robertson, K.M.; Scott, A.V.; Stone, G.N.; et al. Where is the UK’s pollinator biodiversity? The importance of urban areas for flower-visiting insects. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20142849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, D.M.; Camilo, G.R.; Tonietto, R.K.; Ollerton, J.; Ahrné, K.; Arduser, M.; Ascher, J.S.; Baldock, K.C.R.; Fowler, R.; Frankie, G.; et al. The city as a refuge for insect pollinators. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michener, C.D. The Bees of the World, 2nd ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ascher, J.S.; Pickering, J. Discover Life bee species guide and world checklist (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila). 2020. Available online: http://www.discoverlife.org/mp/20q?guide=Apoidea_species (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Kasparek, M. The Resin and Wool Carder Bees (Anthidiini) of Europe and Western Turkey: Identification, Distribution, Biology; Chimaira Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, A.; Schildroth, D.A.; Starks, P.T. Nest site selection in the European wool-carder bee, Anthidium manicatum, with methods for an emerging model species. Apidologie 2011, 42, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, K.K.; Brown, S.; Clarke, S.; Röse, U.S.; Starks, P.T. The European wool-carder bee (Anthidium manicatum) eavesdrops on plant volatile organic compounds (VOCs) during trichome collection. Behav. Process. 2017, 144, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latini, A.; Papagni, I.; Gatti, L.; De Rossi, P.; Campiotti, A.; Giagnacovo, G.; Mirabile Gattia, D.; Mariani, S. Echium vulgare and Echium plantagineum: A comparative study to evaluate their inclusion in Mediterranean urban green roofs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.; Beenaerts, N.; Artois, T. Green roofs and pollinators, useful green spots for some wild bee species (Hymenoptera: Anthophila), but not so much for hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorvillo, C.; Malabusini, S.; Holzer, E.; Frasnelli, M.; Giovanetti, M.; Lavazza, A.; Lupi, D. Urban green areas: Examining honeybee pathogen spillover in wild bees through shared foraging niches. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanetti, M.; Giuliani, C.; Boff, S.; Fico, G.; Lupi, D. A botanic garden as a tool to combine public perception of nature and life-science investigations on native/exotic plants interactions with local pollinators. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, C.; Giovanetti, M.; Lupi, D.; Mesiano, M.P.; Barilli, R.; Ascrizzi, R.; Flamini, G.; Fico, G. Tools to tie: Flower characteristics, voc emission profile, and glandular trichomes of two mexican salvia species to attract bees. Plants 2020, 9, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittlesey, J. The Plant Lover’s Guide to Salvias; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Salerno, G.; Rebora, M.; Piersanti, S.; Saitta, V.; Gorb, E.; Gorb, S. Coleoptera claws and trichome interlocking. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 2023, 209, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, D.; Chakraborty, A.; Biswas, T.; Meher, D.; Singh, A.P. Role of trichomes in plant defence–A crop specific review. Crop. Res. 2022, 57, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, C.; Ascrizzi, R.; Lupi, D.; Tassera, G.; Santagostini, L.; Giovanetti, M.; Flamini, G.; Fico, G. Salvia verticillata: Linking glandular trichomes, volatiles and pollinators. Phytochem 2018, 155, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, C.; Ascrizzi, R.; Tani, C.; Bottoni, M.; Bini, L.M.; Flamini, G.; Fico, G. Salvia uliginosa Benth.: Glandular trichomes as bio-factories of volatiles and essential oil. Flora 2017, 233, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wester, P.; Claßen-Bockhoff, R. Pollination syndromes of New World Salvia species with special reference to bird pollination. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2011, 98, 101–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geslin, B.; Le Féon, V.; Kuhlmann, M.; Vaissière, B.E.; Dajoz, I. The bee fauna of large parks in downtown Paris, France. Ann. Soc. Entomol. 2013, 49, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, L.; Park, M.; Gibbs, J.; Danforth, B. The challenge of accurately documenting bee species richness in agroecosystems: Bee diversity in eastern apple orchards. Ecol. Evol. 2013, 3, 3125–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layek, U.; Das, N.; Samanta, A.; Karmakar, P. impact of seasonal atmospheric factors and photoperiod on floral biology, plant–pollinator interactions, and plant reproduction on Turnera ulmifolia L. (Passifloraceae). Biology 2025, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. 2020. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Burgos, E.; Ceva, H.; Perazzo, R.P.; Devoto, M.; Medan, D.; Zimmermann, M.; Delbue, A.M. Why nestedness in mutualistic networks? J. Theor. Biol. 2007, 249, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harder, L.D. Functional differences of the proboscides of short- and long-tongued bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea). Can. J. Zool. 1983, 61, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenster, C.B.; Armbruster, W.S.; Wilson, P.; Dudash, M.R.; Thomson, J.D. Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 35, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Topfl, W.; Amiet, F. Collection of extrafloral trichome secretions for nest wool impregnation in the solitary bee Anthidium manicatum. Naturwissenschaften 1996, 83, 230–232. [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie, J.E.; Forrest, J.R. Interactions between bee foraging and floral resource phenology shape bee populations and communities. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2017, 21, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanelles-Abella, J.; Fontana, S.; Fournier, B.; Frey, D.; Moretti, M. Low resource availability drives feeding niche partitioning between wild bees and honeybees in a European city. Ecol. Appl. 2023, 33, e2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severinghaus, L.L.; Kurtak, B.H.; Eickwort, G.C. The reproductive behavior of Anthidium manicatum (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) and the significance of size for territorial males. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1981, 9, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, P.; Kopka, S.; Schmoll, G. Phenology of two territorial solitary bees, Anthidium manicatum and A. florentinum (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). J. Zool. 1992, 228, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, L.; Buian, F.M.; Chiesa, F.; Zandigiacomo, P. Note biologiche su Anthidium florentinum nell’Italia nord-orientale (Hymenoptera, Megachilidae). Boll. Soc Nat. Silvia Zenari Pordenone 2013, 37, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Seidelmann, K. Territoriality is just an option: Allocation of a resource fundamental to the resource defense polygyny in the European wool carder bee, Anthidium manicatum (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2021, 75, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, K.K.; Eaton, K.; Obrien, I.; Starks, P.T. Anthidium manicatum, an invasive bee, excludes a native bumble bee, Bombus impatiens, from floral resources. Biol. Invasions 2019, 21, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staab, M.; Pereira-Peixoto, M.H.; Klein, A.M. Exotic garden plants partly substitute for native plants as resources for pollinators when native plants become seasonally scarce. Oecologia 2020, 194, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, K.; Thomas, F.; Bekessy, S. The role of ‘nativeness’ in urban greening to support animal biodiversity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 205, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, M.E.; Awbi, A.J.; Franco, M. Going native? Flower use by bumblebees in English urban gardens. Ann. Bot. 2014, 113, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, J.C.; Morales, C.L. Ecological impacts of invasive alien species on bees. Apidologie 2009, 40, 388–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Castaño, A.; Vilà, M. Impact of landscape alteration and invasions on pollinators: A meta-analysis. J. Ecol. 2012, 100, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verloove, F. Perovskia. In Manual of the alien plants of Belgium; Botanic Garden of Meise: Meise, Belgium, 2014; Available online: http://alienplantsbelgium.be/content/perovskia (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Soper, J.; Beggs, J. Assessing the impact of an introduced bee, Anthidium manicatum, on pollinator communities in New Zealand. N. Z. J. Bot. 2013, 51, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggar, A.K.; McGrath, E.; Despland, E. Competition between a native and introduced pollinator in unmanaged urban meadows. Biol. Invasions 2021, 23, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, C.; Bottoni, M.; Milani, F.; Spada, A.; Falsini, S.; Papini, A.; Fico, G. An integrative approach to selected species of Tanacetum L. (Asteraceae): Insights into morphology and phytochemistry. Plants 2024, 13, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Calyx Length | Flower Length | Upper Lip Length | Lower Lip Length | Length of the Corolla Tube | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 5.90 | 8.85 | 3.86 | 2.69 | 4.99 |

| SD | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.46 |

| Min | 4.81 | 7.85 | 3.25 | 2.45 | 4.01 |

| Max | 6.87 | 9.87 | 4.25 | 2.96 | 5.82 |

| Stainings | Target Compounds | Capitate Trichomes | Peltate Trichomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoral Yellow-088 | Total lipids | − | ++ |

| Nile Red | Neutral lipids | − | ++ |

| Nadi reagent | Terpenoids | − | ++ |

| PAS reagent | Total polysaccharides | + | − |

| Ruthenium Red | Acid polysaccharides | ± | − |

| Alcian Blue | Muco-polysaccharides | + | − |

| FeCl3 | Polyphenols | ++ | − |

| AlCl3 | Flavonoids | + | − |

| PdV | CL | BAM | PU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthidium spp. | 12.54 ± 9.68 Ba | 18.91 ± 9.49 Aa | 9.15 ± 9.39 BCa | 5.19 ± 7.47 Ca |

| Apis mellifera | 3.45 ± 2.80 Ab | 5.54 ± 3.66 Ab | 4.76 ± 4.11 Aab | 2.89 ± 2.23 Aa |

| Bombus spp. | 1.45 ± 0.94 Ab | 2.96 ± 1.74 Ab | 1.17 ± 0.41 Ab | 1.29 ± 0.71 Aa |

| Resource collected | Nectar and Pollen | Nectar | Nectar | Nectar and Pollen |

| Number of bee genera | 7 | 3 | 5 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lupi, D.; Giuliani, C.; Fico, G.; Malabusini, S.; Sorvillo, C.; Giovanetti, M. Enhancing Pollinator Support: Plant–Pollinator Dynamics Between Salvia yangii and Anthidium Bees in Anthropogenic Landscapes. Biology 2025, 14, 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081084

Lupi D, Giuliani C, Fico G, Malabusini S, Sorvillo C, Giovanetti M. Enhancing Pollinator Support: Plant–Pollinator Dynamics Between Salvia yangii and Anthidium Bees in Anthropogenic Landscapes. Biology. 2025; 14(8):1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081084

Chicago/Turabian StyleLupi, Daniela, Claudia Giuliani, Gelsomina Fico, Serena Malabusini, Carla Sorvillo, and Manuela Giovanetti. 2025. "Enhancing Pollinator Support: Plant–Pollinator Dynamics Between Salvia yangii and Anthidium Bees in Anthropogenic Landscapes" Biology 14, no. 8: 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081084

APA StyleLupi, D., Giuliani, C., Fico, G., Malabusini, S., Sorvillo, C., & Giovanetti, M. (2025). Enhancing Pollinator Support: Plant–Pollinator Dynamics Between Salvia yangii and Anthidium Bees in Anthropogenic Landscapes. Biology, 14(8), 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081084