Comparative Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis Revealed Key Pathways and Hub Genes Related to Gill Raker Development in Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish Preparation and Experimental Design

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

2.4. Total RNA Isolation and Sequencing

2.5. Analysis of RNA-Seq Data

2.6. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Changes in Gill Rakers of Silver Carp Across Developmental Stages

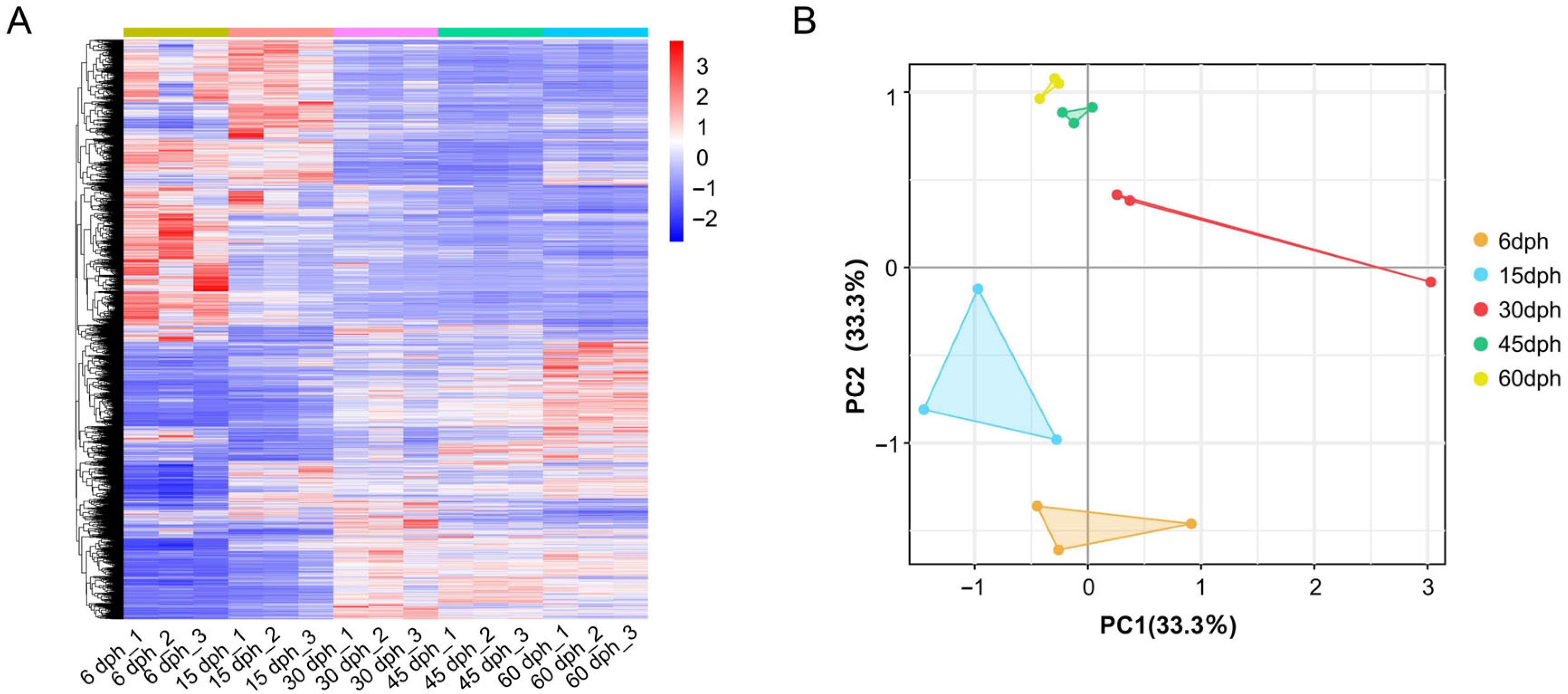

3.2. The Quality Assessment of Transcriptome Data

3.3. Differential Gene Expression Analysis During Gill Raker Development

3.4. GO Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

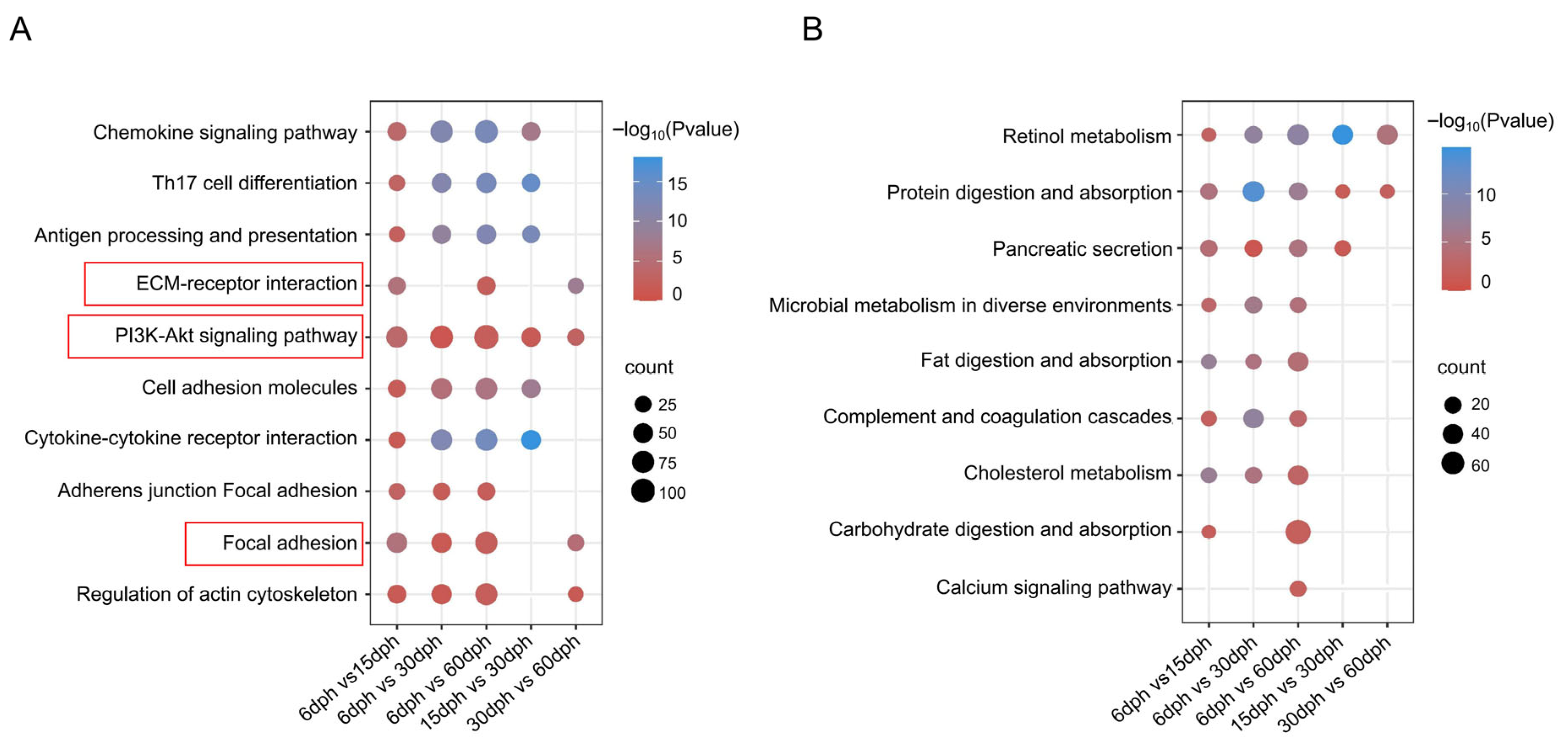

3.5. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

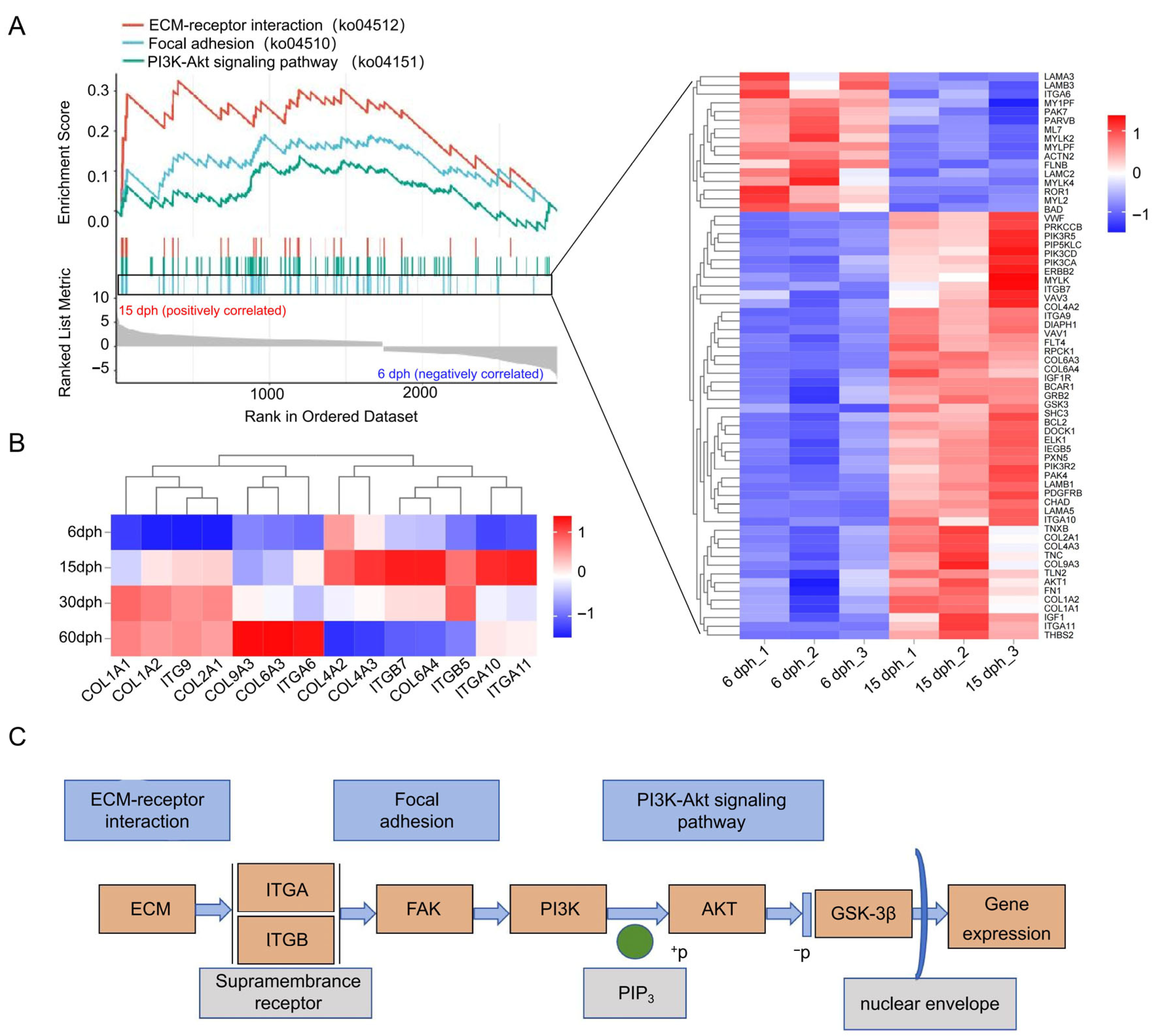

3.6. GSEA of Focal Adhesion, ECM-Receptor Interaction, and PI3K-Akt Signaling Pathway

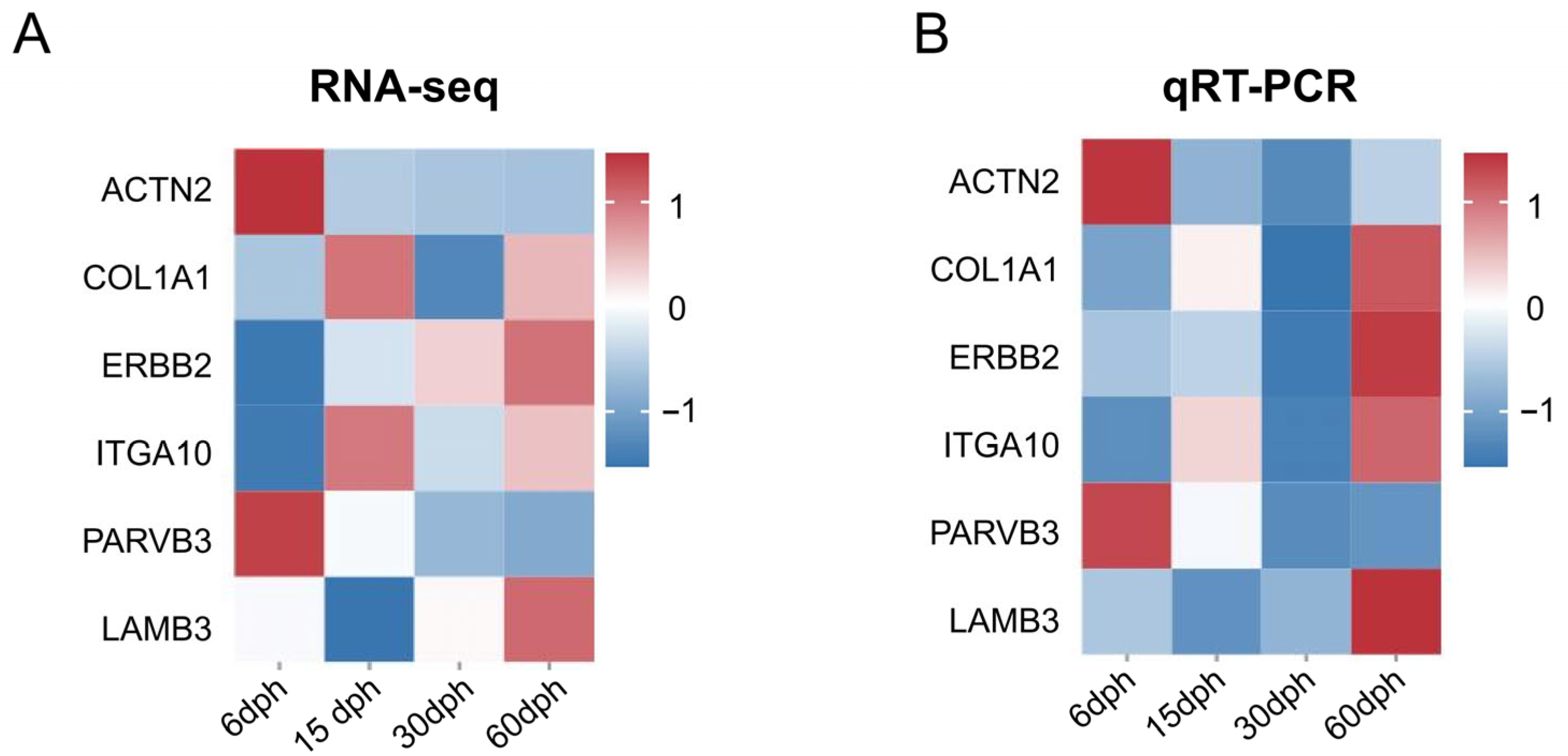

3.7. Valadation of RNA-Seq by Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| dph | days post-hatching |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| GR | Gill raker |

| GF | Gill filament |

| GA | Gill arch |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| COL | Collagen |

| ITG | Integrins |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| CNCB | China National Center for Bioinformation |

| GSA | Genome Sequence Archive |

References

- Hochstrasser, J.M.; Collins, S.F. Assessing the direct and indirect effects of bigheaded carp (Hypophthalmichthys spp.) on freshwater food webs: A meta-analysis. Freshw. Biol. 2024, 69, 1399–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, L.; Schreiber, K.; Hagenmeyer, J.; Eduardo, S.; Spanke, T.; Blanke, A. Diversity of filter feeding and variations in cross-flow filtration of five ram-feeding fish species. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1253083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, K.E.; Hernandez, L.P. Making a master filterer: Ontogeny of specialized filtering plates in silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix). J. Morphol. 2018, 279, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheer, A.; Cheung, S.; Hung, T.-C.; Piedrahita, R.H.; Sanderson, S.L. Computational Fluid Dynamics of Fish Gill Rakers During Crossflow Filtration. Bull. Math. Biol. 2011, 74, 981–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, S.L.; Cheer, A.Y.; Goodrich, J.S.; Graziano, J.D.; Callan, W.T. Crossflow filtration in suspension-feeding fishes. Nature 2001, 412, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangelosi, A.A.; Mays, N.L.; Balcer, M.D.; Reavie, E.D.; Reid, D.M.; Sturtevant, R.; Gao, X. The response of zooplankton and phytoplankton from the North American Great Lakes to filtration. Harmful Algae 2007, 6, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, R.J.; Mayzaud, P. Utilization of Phytoplankton by Zooplankton during the Spring Bloom in a Nova Scotia Inlet. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1984, 41, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahilainen, K.K.; Siwertsson, A.; Gjelland, K.Ø.; Knudsen, R.; Bøhn, T.; Amundsen, P.-A. The role of gill raker number variability in adaptive radiation of coregonid fish. Evol. Ecol. 2010, 25, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, P.A.; Bøhn, T.; Vaga, G.H. Gill raker morphology and feeding ecology of two sympatric morphs of European whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus). Ann. Zool. Fenn. 2004, 41, 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Cui, Y.; Li, Z. Dietary-morphological relationships of fishes in Liangzi Lake, China. J. Fish Biol. 2001, 58, 1714–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkli, K.; Østbye, K.; Kahilainen, K.K.; Amundsen, P.; Præbel, K. Diversifying selection drives parallel evolution of gill raker number and body size along the speciation continuum of European whitefish. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 2617–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, D.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhu, S. Analysis of Fish Community Structure and Environmental Impact in the Xijiang River Southern. Fish. Sci. 2020, 16, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Witkop, E.M.; Van Wassenbergh, S.; Heideman, P.D.; Sanderson, S.L. Biomimetic models of fish gill rakers as lateral displacement arrays for particle separation. Bioinspiration Biomim. 2023, 18, 056009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P. Silver Carp and Bighead Carp, and Their Use in the Control of Algal Blooms; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, F.; Zou, G.; Feng, C.; Sha, H.; Liu, S.; Liang, H. Physiological responses and molecular strategies in heart of silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) under hypoxia and reoxygenation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2021, 40, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Zhu, W. Research on the Postembryonic, Development Biology of the Filtering-feeding organs of Silver carp. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 1993, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Battonyai, I.; Specziár, A.; Vitál, Z.; Mozsár, A.; Görgényi, J.; Borics, G.; Tóth, L.G.; Boros, G. Relationship between gill raker morphology and feeding habits of hybrid bigheaded carps (Hypophthalmichthys spp.). Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2015, 416, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, K.E.; George, A.E.; Chapman, D.C.; Chick, J.H.; Hernandez, L.P. Developmental ecomorphology of the epibranchial organ of the silver carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix. J. Fish Biol. 2020, 97, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ling, C.; Wang, Q.; Feng, C.; Luo, X.; Sha, H.; He, G.; Zou, G.; Liang, H. Hypoxia Stress Induces Tissue Damage, Immune Defense, and Oxygen Transport Change in Gill of Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix): Evaluation on Hypoxia by Using Transcriptomics. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 900200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, F.; Bao, M.; Liu, F.; Hu, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, C.; Qiu, X.; et al. Transcriptome profiling of tiger pufferfish (Takifugu rubripes) gills in response to acute hypoxia. Aquaculture 2022, 557, 738324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Li, F.; Lu, J.; Wen, Y.; Li, Z.; Liao, J.; Cao, J.; He, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, Q. Transcriptome analysis in gill reveals the adaptive mechanism of domesticated common carp to the high temperature in shallow rice paddies. Aquaculture 2024, 578, 740107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondeau-Bidet, E.; Tine, M.; Gonzalez, A.A.; Guinand, B.; Lorin-Nebel, C. Coping with salinity extremes: Gill transcriptome profiling in the black-chinned tilapia (Sarotherodon melanotheron). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Zhu, S.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Elevated Temperatures Shorten the Spawning Period of Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) in a Large Subtropical River in China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 708109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q. Experimental observation on the effects of bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) on the plankton and water quality in ponds. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 56658–56675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Li, X.; Sha, H.; Luo, X.; Zou, G.; Zhang, J.; Liang, H. A 5′ Promoter Region SNP in CTSC Leads to Increased Hypoxia Tolerance in Changfeng Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix). Animals 2025, 15, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Q.; Vickers, K.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Samuels, D.C.; Koues, O.; Shyr, Y.; Guo, Y. Multi-perspective quality control of Illumina RNA sequencing data analysis. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2016, 16, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, S.J. Read trimming has minimal effect on bacterial SNP-calling accuracy. Microb. Genom. 2020, 6, e000434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, R.V.; Pongor, L.S.; Mariño-Ramírez, L.; Landsman, D. TPMCalculator: One-step software to quantify mRNA abundance of genomic features. Bioinformatics 2018, 35, 1960–1962. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Wang, F.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y. Three Differential Expression Analysis Methods for RNA Sequencing: Limma, EdgeR, DESeq2. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2021, 175, e62528. [Google Scholar]

- Van Aken, B. Response to the note to editor: Comments on “transcriptomic response of Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls (OH-PCBs)”. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2019, 22, 224–225. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Hu, E.; Cai, Y.; Xie, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhan, L.; Tang, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, R.; et al. Using clusterProfiler to characterize multiomics data. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 3292–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhou, T.; Cao, J.; Zou, G.; Liang, H. Comparative transcriptome sequencing and weighted coexpression network analysis reveal growth-related hub genes and key pathways in the Chinese soft-shelled turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis). Water Biol. Secur. 2024, 3, 100286. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Auwera, G.A.; Carneiro, M.O.; Hartl, C.; Poplin, R.; Del Angel, G.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Jordan, T.; Shakir, K.; Roazen, D.; Thibault, J.; et al. From FastQ Data to High-Confidence Variant Calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit Best Practices Pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2013, 43, 11.10.1–11.10.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.; Pham, A.K.; Gonen, A.; Navia-Pelaez, J.M.; Xia, K.; Park, S.; Osterman, A.L.; Bacon, K.; Beaton, G.; Kurten, R.C.; et al. Reduced AIBP expression in bronchial epithelial cells of asthmatic patients: Potential therapeutic target. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2022, 52, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Xie, P.; Xu, J.; Ke, Z.; Guo, L. Growth and food availability of silver and bighead carps: Evidence from stable isotope and gut content analysis. Aquac. Res. 2009, 40, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, M.C.; Smitherman, R.O. Food habits and growth of silver and bighead carp in cages and ponds. Aquaculture 1980, 20, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, H.R.; Johal, M.S. Food and feeding habits of silver carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Val. 1844) in Gobindsagar Reservoir, India. Int. J. Aquat. Biol. 2015, 3, 225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Walleser, L.R.; Howard, D.R.; Sandheinrich, M.B.; Gaikowski, M.P.; Amberg, J.J. Confocal microscopy as a useful approach to describe gill rakers of Asian species of carp and native filter-feeding fishes of the upper Mississippi River system. J. Fish Biol. 2014, 85, 1777–1784. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Xavier, J.; Tamhankar, S.P.; Amin, R. Discovery of novel small molecule Asparaginyl endopeptidase inhibitors via dual approach-based virtual screening and molecular simulation studies. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, e093291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Schenk, R.; Collins, N.L.; Schenk, N.A.; Beard, D.A. Integrated Functions of Cardiac Energetics, Mechanics, and Purine Nucleotide Metabolism. Compr. Physiol. 2023, 14, 5345–5369. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Xie, N.; Illes, P.; Di Virgilio, F.; Ulrich, H.; Semyanov, A.; Verkhratsky, A.; Sperlagh, B.; Yu, S.-G.; Huang, C.; et al. From purines to purinergic signalling: Molecular functions and human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, S.; Zhai, H.; Tang, M.; Xue, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, L.; Zhong, T.; Dai, D.; Cao, J.; Guo, J.; et al. Profiling and Functional Analysis of mRNAs during Skeletal Muscle Differentiation in Goats. Animals 2022, 12, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balseiro, P.; Moreira, R.; Chamorro, R.; Figueras, A.; Novoa, B. Immune responses during the larval stages of Mytilus galloprovincialis: Metamorphosis alters immunocompetence, body shape and behavior. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2013, 35, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonz, M.G. Cell proliferation and regeneration in the gill. J. Comp. Physiol. B-Biochem. Syst. Environ. Physiol. 2024, 194, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, M.; Bruno, D.; Brilli, M.; Gianfranceschi, N.; Tian, L.; Tettamanti, G.; Caccia, S.; Casartelli, M. Black Soldier Fly Larvae Adapt to Different Food Substrates through Morphological and Functional Responses of the Midgut. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laronha, H.; Caldeira, J. Structure and Function of Human Matrix Metalloproteinases. Cells 2020, 9, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelse, K.; Pöschl, E.; Aigner, T. Collagens—Structure, function, and biosynthesis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2003, 55, 1531–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, S.; Lovisa, S.; Ambrose, C.G.; McAndrews, K.M.; Sugimoto, H.; Kalluri, R. Type-I collagen produced by distinct fibroblast lineages reveals specific function during embryogenesis and Osteogenesis Imperfecta. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Nowlan, N.C. Initiation and emerging complexity of the collagen network during prenatal skeletal development. Eur. Cells Mater. 2020, 39, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estêvão, M.D.; Silva, N.; Redruello, B.; Costa, R.; Gregório, S.; Canário, A.V.M.; Power, D.M. Cellular morphology and markers of cartilage and bone in the marine teleost Sparus auratus. Cell Tissue Res. 2011, 343, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanawong, P.; Calderwood, D.A. Organization, dynamics and mechanoregulation of integrin-mediated cell–ECM adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeser, R.F. Integrins and chondrocyte–matrix interactions in articular cartilage. Matrix Biol. 2014, 39, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Roy, S.R.; Jin, C.; Li, G.; Zhang, Q.; Asano, N.; Asahina, S.; Kajiwara, T.; Takahara, A.; Feng, B.; et al. Control cell migration by engineering integrin ligand assembly. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Guo, L.; Zhang, H.; Ge, J.; Luo, J.; Song, K.; Zhao, L.; Yang, S. Hypoxia induces reversible gill remodeling in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) through integrins-mediated cell adhesion. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 154, 109918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnoodi, J.; Pedchenko, V.; Hudson, B.G. Mammalian collagen IV. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2008, 71, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrullo, G.; Filomeni, G.; Rizza, S. Redox regulation of focal adhesions. Redox Biol. 2025, 80, 103514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, G.B.; Zaharias, R.; Seabold, D.; Stanford, C. Integrin-associated tyrosine kinase FAK affects Cbfa1 expression. J. Orthop. Res. 2011, 29, 1443–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, J.T. Focal adhesion kinase: The first ten years. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelman, J.A.; Luo, J.; Cantley, L.C. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006, 7, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, B.D.; Cantley, L.C. AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating Downstream. Cell 2007, 129, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | 6 dph | 15 dph | 30 dph | 45 dph | 60 dph |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total length (mm) | 7.74 ± 0.55 | 11.82 ± 0.92 | 16.58 ± 2.46 | 28.94 ± 3.93 | 48.43 ± 5.29 |

| Body weight (mg) | 1.50 ± 0.90 | 11.03 ± 1.94 | 84.07 ± 4.39 | 376 ± 31.63 | 1026.27 ± 297.35 |

| Feeding styles [16] | Swallowing stage (Zooplankton) [16] | Dietary transition stage (Zooplankton & phytoplankton) [16] | Filter-feeding stage (Phytoplankton) [16] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Geng, Z.; Feng, C.; Liang, H. Comparative Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis Revealed Key Pathways and Hub Genes Related to Gill Raker Development in Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix). Biology 2025, 14, 1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121797

Li X, Geng Z, Feng C, Liang H. Comparative Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis Revealed Key Pathways and Hub Genes Related to Gill Raker Development in Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix). Biology. 2025; 14(12):1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121797

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaohui, Ziyang Geng, Cui Feng, and Hongwei Liang. 2025. "Comparative Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis Revealed Key Pathways and Hub Genes Related to Gill Raker Development in Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix)" Biology 14, no. 12: 1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121797

APA StyleLi, X., Geng, Z., Feng, C., & Liang, H. (2025). Comparative Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis Revealed Key Pathways and Hub Genes Related to Gill Raker Development in Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix). Biology, 14(12), 1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121797