Seasonal Variation of Shoreline Fish Assemblages at Two Stations in the Southern Branch of the Yangtze River Estuary

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Sites and Fishing Gears

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Biodiversity Index

2.2.2. Ecological Guild Classification

2.2.3. Dominant Species

2.2.4. Composition Similarity

2.2.5. Community Seasonal Alternation and Migration Indices

2.2.6. Abundance Biomass

3. Results

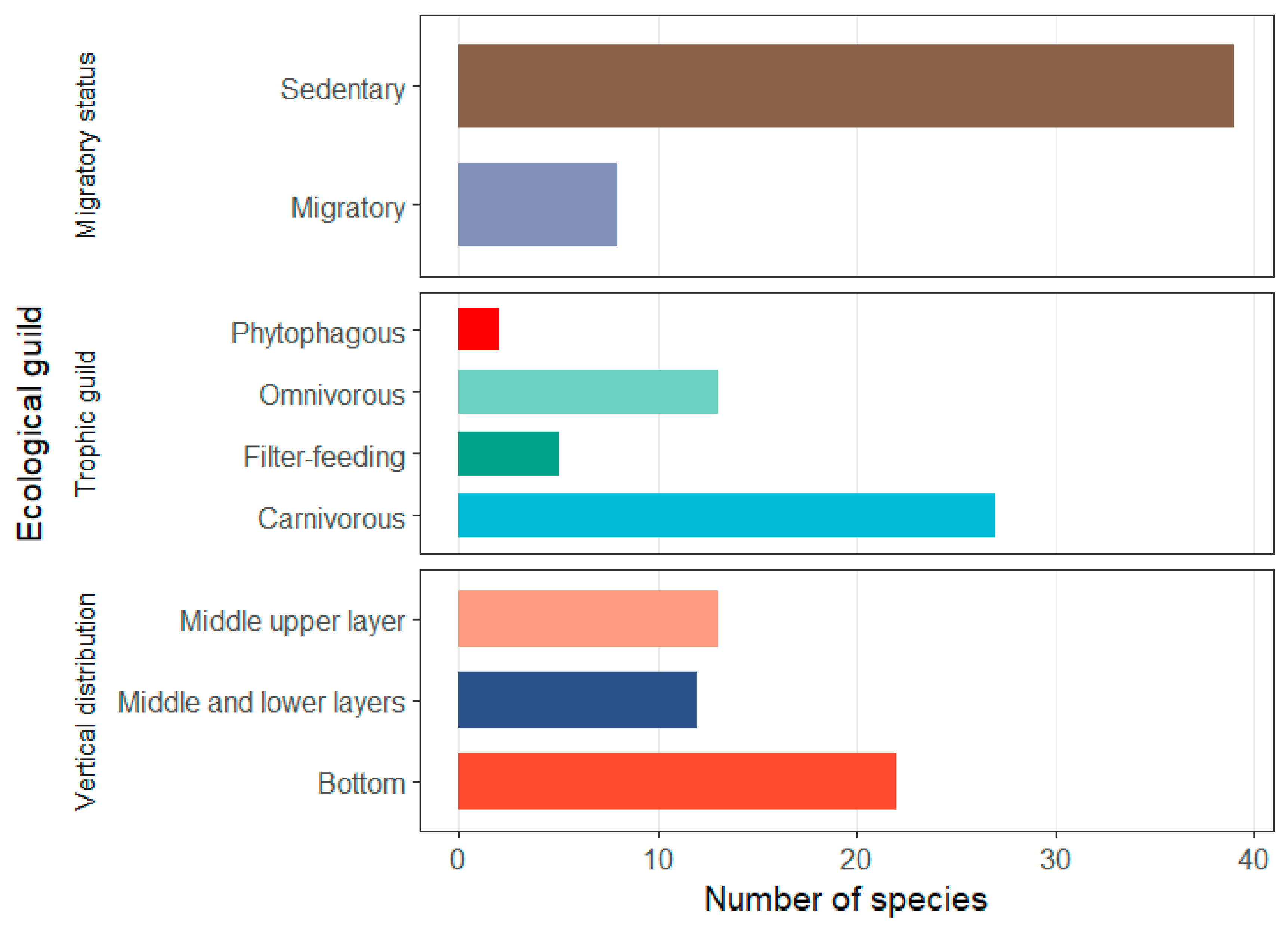

3.1. Species Composition and Ecological Guilds of Intertidal Fish Assemblages

3.2. Analysis of Dominant Fish Species

3.3. Intertidal Fish Assemblages

3.4. Seasonal Similarity of the Fish Assemblages

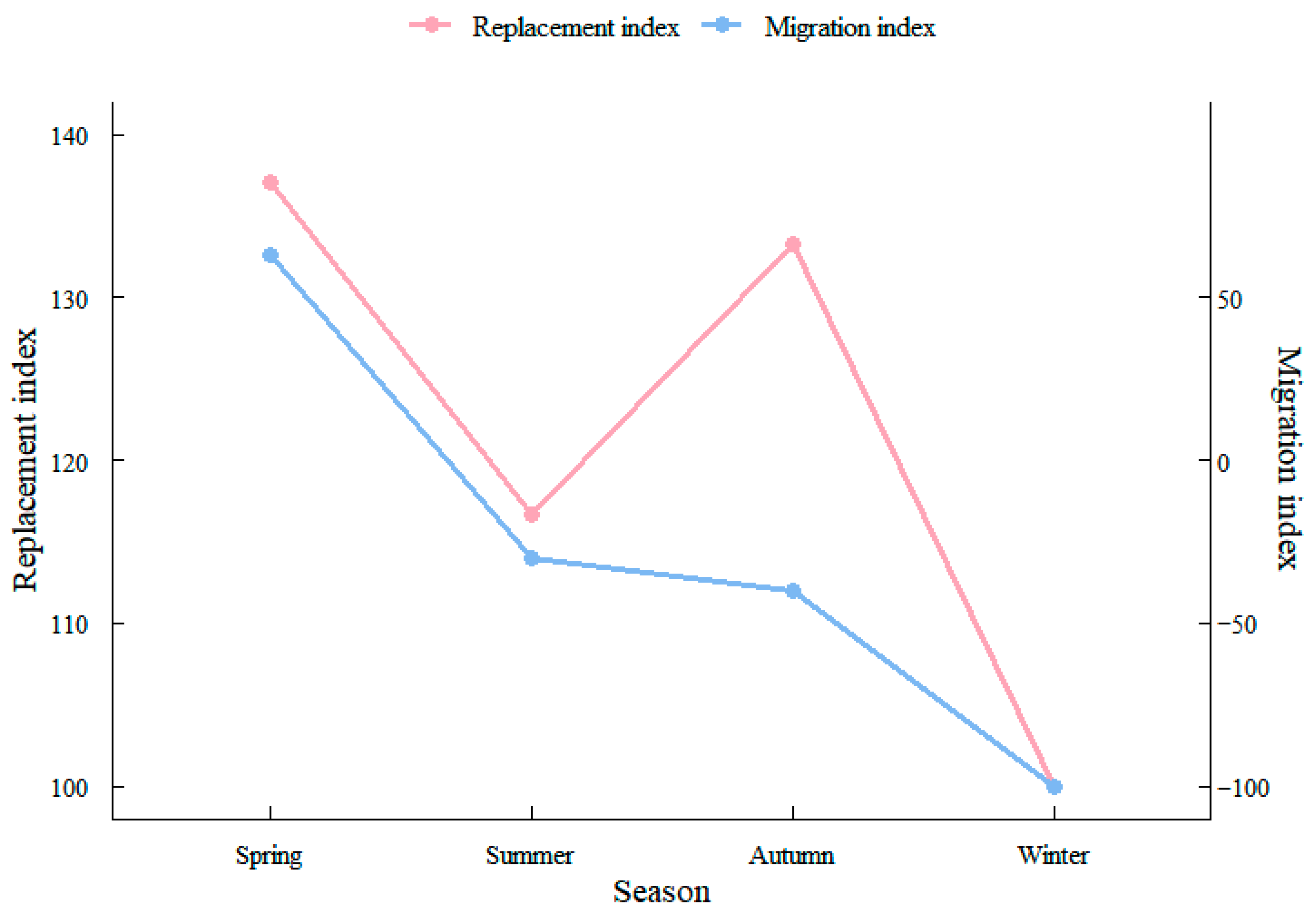

3.5. Seasonal Changes in Fish Assemblages

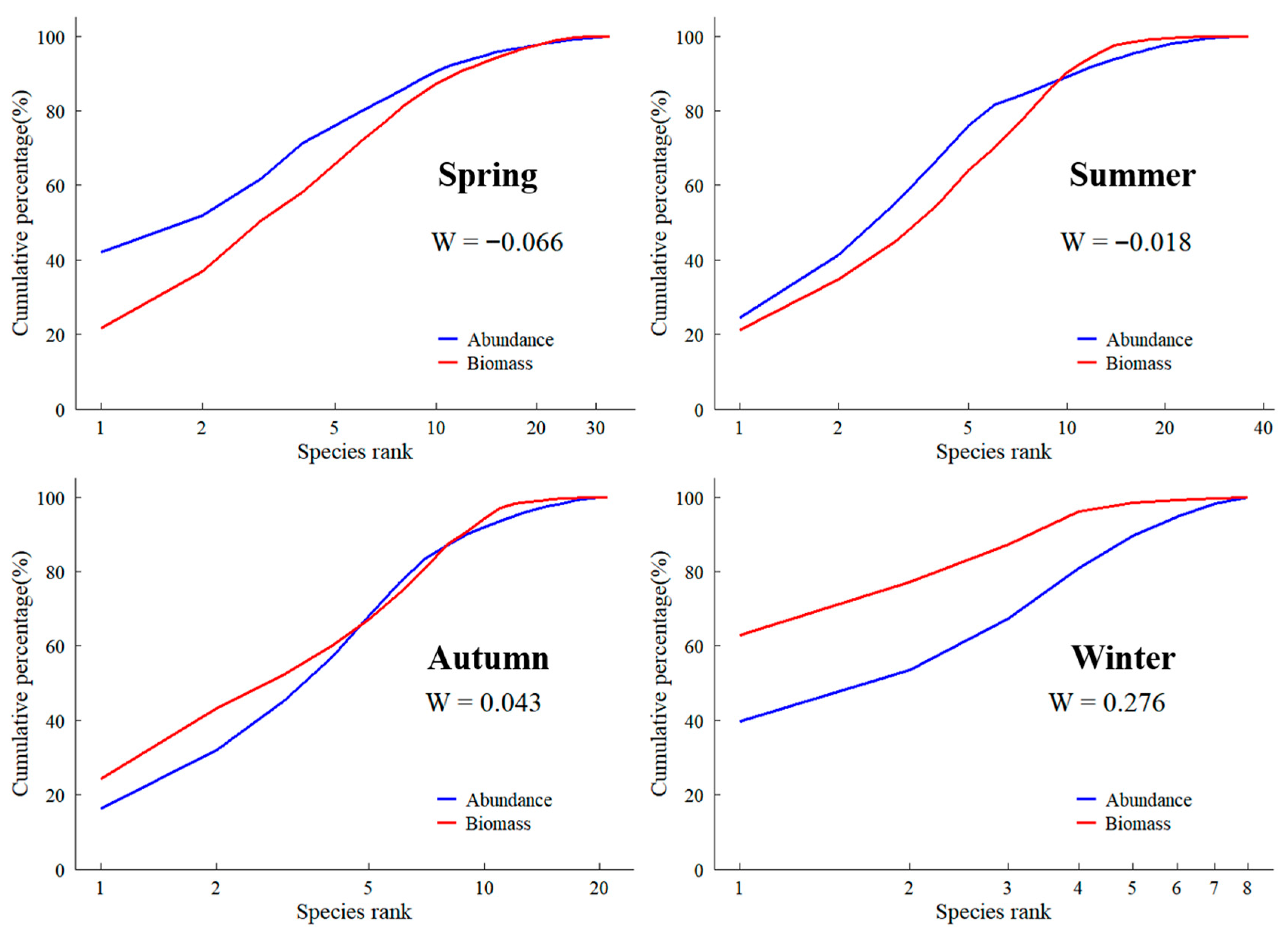

3.6. Abundance-Biomass Comparison (ABC) Curves

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Species Composition and Ecological Types

4.2. Fish Diversity, Community Stability, and Potential Relevance to Habitat Assessments

4.3. Study Significance and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, S.; Wang, H.; Liang, D.; Li, Y.; Shen, Z. How the Yangtze River transports microplastics to the East China Sea. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindong, R.; Chen, J.; Dai, L.; Gao, C.; Han, D.; Tian, S.; Wu, J.; Ma, Q.; Tang, J. The effect of environmental conditions on seasonal and inter-annual abundance of two species in the Yangtze River estuary. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2021, 72, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.J.; Chen, X.Z.; Cheng, J.H.; Wang, Y.L.; Shen, X.Q.; Chen, W.Z.; Li, C.S. Biological Resources and Environment of the East China Sea Continental Shelf; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G. Fish Community Structure in the Yangtze Estuary and Its Correlation with Key Environmental Factors. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. Food web structure and energy flow in the Yangtze River Estuary: Implications for ecosystem management. Ecol. Model. 2019, 403, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.B.; Cao, W.X. History and prospects of Acipenser sinensis species conservation. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 1999, 23, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/categories-and-criteria (accessed on 12 December 2004).

- Wei, Q.W. Reproductive Behavioral Ecology and Resource Assessment of Acipenser Sinensis. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, F.; Fang, D.D.; Zhang, H.; Li, J. Protection and development after the ten-year fishing ban in the Yangtze River. J. Fish. China 2023, 47, 245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Zhuang, P.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, L.Z. Impacts of habitat fragmentation on the migration and population dynamics of Chinese sturgeon (Acipenser sinensis). Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2021, 31, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, T.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhuang, P. Migration and feeding habits of juvenile Chinese sturgeon (Acipenser sinensis, Gray 1835) in the Yangtze Estuary: Implications for conservation. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2018, 28, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhuang, P.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.L.; Hou, J.L.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, L.Z. Isosmotic points and their ecological significance for juvenile Chinese sturgeon (Acipenser sinensis). J. Fish Biol. 2015, 86, 1416–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, L.Z.; Kynard, B. New evidence may support the persistence and adaptability of the near-extinct Chinese sturgeon. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 193, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Zhuang, P.; Zhang, L.Z.; Wang, Y. Food composition and feeding habits of juvenile Acipenser sinensis in the Yangtze Estuary. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008, 19, 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, P.; Luo, G.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y. Feeding habits and food competition between juvenile Acipenser sinensis and six major economic fish species in the Yangtze Estuary. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2010, 30, 5544–5554. [Google Scholar]

- Grenouillet, G.; Pont, D.; Seip, K.L. Abundance and species richness as a function of food resources and vegetation structure: Juvenile fish assemblages in rivers. Ecography 2002, 25, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.O.; Henderson, B.A.; Bax, N.J.; Marshall, T.R.; Oglesby, R.T.; Christie, W.J. Concepts and methods of community ecology applied to freshwater fisheries management. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1987, 44, S448–S470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.S. Spatial and Temporal Distribution Patterns of Fish Diversity in Salt Marsh Creeks of the Yangtze Estuary. Master’s Thesis, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Loreau, M.; de Mazancourt, C. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability: A synthesis of underlying mechanisms. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, M.W.; Heck, K.L.; Able, K.W.; Childers, D.L.; Eggleston, D.B.; Gillanders, B.M.; Halpern, B.; Hays, C.G.; Hoshino, K.; Minello, T.J.; et al. The identification, conservation, and management of estuarine and marine nurseries for fish and invertebrates. BioScience 2001, 51, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P. Fish of the Yangtze Estuary; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, M.; Dewailly, F. The structure and components of European estuarine fish assemblages. Neth. J. Aquat. Ecol. 1995, 29, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, P. The distribution of the flora in the alpine zone.1. New Phytol. 1912, 11, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Jia, X.; Li, Y.; He, M.; Tan, X.; Wang, C.; Jiang, W. Evolvement and diversity of fish community in Xijiang River. J. Fish. Sci. China 2010, 17, 298–311. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.J.; Zhu, X.H.; Wu, H.Z.; Xu, F.S.; Ye, M.Z. Study on the diversity of swimming animal communities and related factors in the coastal waters of the Yellow and Bohai Seas. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 1994, 16, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation, 2nd ed.; PRIMER-E Ltd.: Plymouth, UK, 2001; pp. 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Huang, J.L.; Chen, J.H.; Li, B.; Zhao, J.; Gao, C.X.; Wang, X.F.; Tian, S.Q. Spatio-temporal distribution and influencing factors of fish resources in the Yangtze Estuary based on GAM. J. Fish. China 2020, 44, 936–946. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.P.; Xu, B.D.; Ye, Z.J.; Li, X. Preliminary study on the structural characteristics of fishery resource communities in spring and autumn in the coastal waters of Qingdao. J. Ocean Univ. China (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2005, 35, 792–798. [Google Scholar]

- Buchheister, A.; Bonzek, C.F.; Gartland, J.; Latour, R.J. Patterns and drivers of the demersal fish community of Chesapeake Bay. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2013, 481, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Reich, P.B.; Knops, J.M.H. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability in a decade-long grassland experiment. J. Nat. 2006, 441, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, R.M. A new method for detecting pollution effects on marine macrobenthic communities. Mar. Biol. 1986, 92, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Gao, C.X.; Tian, S.Q.; Li, Y. Interannual variation in fish community structure diversity in Dianshan Lake. J. Shanghai Ocean Univ. 2014, 23, 403–410. [Google Scholar]

| Species | 2024 | Ecological Guild | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | ||

| Cyperiniformes | |||||

| Parabramis pekinensis | 80 | 327 | 58 | 0 | Fr, S, C, U |

| Culter alburnus | 38 | 271 | 32 | 0 | Fr, S, C, U |

| Saurogobio dumerili | 4 | 42 | 5 | 0 | Fr, S, C, D |

| Pseudobrama simoni | 22 | 6 | 2 | 0 | Fr, S, O, L |

| Cyprinus carpio | 6 | 21 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, O, L |

| Hemiculter bleekeri | 17 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, O, U |

| Squaliobarbus curriculus | 8 | 7 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, C, U |

| Hypophthalmichthys molitrix | 3 | 18 | 6 | 0 | Fr, S, H, U |

| Aristichthys nobilis | 2 | 27 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, Fi, U |

| Culter oxycephalus | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, O, U |

| Xenocypris davidi | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fr, R, O, L |

| Elopichthys bambusa | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, C, D |

| Carassius auratus | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, O, D |

| Ctenopharyngodon idella | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, H, D |

| Hemibarbus maculatus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, C, L |

| Pseudobrama simoni | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, O, L |

| Myxocyprinus asiaticus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fr, R, C, L |

| Xenocyprisargentea | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, O, L |

| Cultrichthys erythropterus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, C, U |

| Culter mongolicus | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, C, L |

| Mylopharyngodon piceus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, O, L |

| Perciformes | |||||

| Lateolabrax japonicus | 25 | 108 | 80 | 23 | Es, R, C, U |

| Odontamblyopus lacepedii | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 | Es, S, O, D |

| Channa argus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, C, D |

| Chaemrichthys stigmatias | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Es, S, C, D |

| Tridentiger trigonocephalus | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | Es, S, C, D |

| Eleutheronema tetradactylum | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | Es, S, C, D |

| Caranx sexfasciatus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Ma, S, C, U |

| Collichthys lucidus | 0 | 0 | 78 | 5 | Ma, S, C, D |

| Miichthys miiuy | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | Ma, S, C, D |

| Acanthogobius ommaturus | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | Es, S, C, D |

| Boleophthalmus pectinirostris | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Es, S, Fi, D |

| Siluriformes | |||||

| Pelteobaggrus nitidus | 34 | 12 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, C, D |

| Leiocassis longirostris | 7 | 34 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, C, L |

| Silurus asotus | 22 | 38 | 8 | 2 | Fr, S, C, D |

| Tetraodontiformes | |||||

| Takifugu xanthopterus | 2 | 14 | 0 | 0 | Es, S, C, D |

| Takifugu obscurus | 0 | 14 | 9 | 1 | Mi, S, C, D |

| Herring order | |||||

| Coilia nasus | 344 | 475 | 66 | 3 | Mi, R, C, U |

| Coilia mystus | 78 | 26 | 0 | 0 | Mi, R, C, U |

| Pleuroniformes | |||||

| Cynoglossus gracilis | 82 | 224 | 54 | 8 | Es, S, Fi, D |

| Cynoglossus purpureomaculatus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ma, S, Fi, D |

| Mugiliformes | |||||

| Liza haematocheila | 8 | 177 | 18 | 8 | Es, S, C, L |

| Mugil cephalus | 12 | 33 | 44 | 8 | Es, R, O, D |

| Cucurbitaceae | |||||

| Salanx ariakensis kishinouye | 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | Fr, S, Fi, U |

| Anguilliformes | |||||

| Anguilla japonica | 2 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Mi, R, O, D |

| Sturgeons | |||||

| hybrid sturgeon | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Fr, S, O, L |

| Acipenser sinensis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Mi, S, C, L |

| Species Name | IRI | Dominance Rank (by IRI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | |||

| Summer | Coilia nasus | 6339.41 | 2999.38 | 595.66 | Spr. Sum. Aut. | |

| Cynoglossus gracilis | 1477.01 | 1672.79 | 1602.60 | Spr. Sum. Aut. Win. | ||

| Liza haematocheila | 722.10 | 3005.06 | 7666.47 | Sum. Win. | ||

| Parabramis pekinensis | 2519.28 | 2630.96 | — | Spr. Sum. Aut. | ||

| Coilia mystus | 1044.24 | 139.98 | — | — | Spr. | |

| Culter alburnus | 924.78 | 2290.19 | 914.46 | — | Sum. | |

| Lateolabrax japonicus | 605.59 | 1576.38 | 2163.89 | 4855.04 | Sum. Aut. Win. | |

| Mugil cephalus | 927.70 | 769.68 | 3273.45 | 2809.52 | Aut. Win. | |

| Pelteobaggrus nitidus | 524.85 | 68.00 | — | — | ||

| Saurogobio dumerili | 65.88 | 249.83 | 107.96 | — | ||

| Leiocassis longirostris | 383.25 | 568.93 | — | — | ||

| Pseudobrama simoni | 381.62 | 33.77 | 47.65 | — | ||

| Cyprinus carpio | 1452.87 | 1462.72 | — | — | Spr. Sum | |

| Hemiculter bleekeri | 276.79 | 17.98 | — | — | ||

| Odontamblyopus lacepedii | 25.59 | 20.74 | 64.48 | — | ||

| Squaliobarbus curriculus | 165.03 | 61.83 | — | — | ||

| Anguilla japonica | 72.75 | 79.67 | 51.42 | — | ||

| Salanx ariakensis kishinouye | 36.35 | 51.64 | — | — | ||

| Hypophthalmichthys molitrix | 800.20 | 257.19 | 866.43 | — | ||

| Aristichthys nobilis | 204.02 | 615.77 | — | — | ||

| Culter oxycephalus | 81.06 | — | — | — | ||

| Xenocypris davidi | 63.66 | 5.18 | — | — | ||

| Elopichthys bambusa | 18.69 | 237.43 | — | — | ||

| Takifugu xanthopterus | 30.66 | 83.42 | — | — | ||

| Silurus asotus | 354.45 | 444.28 | 856.63 | 1354.02 | Win. | |

| Carassius auratus | — | 42.52 | — | — | ||

| Ctenopharyngodon idella | 41.34 | 184.54 | — | — | ||

| Cynoglossus purpureomaculatus | 14.42 | — | — | — | ||

| Channa argus | 93.92 | — | — | — | ||

| Hemibarbus maculatus | 56.00 | 13.36 | — | — | ||

| Pseudobrama macrops | 60.21 | — | — | — | ||

| Myxocyprinus asiaticus | 17.27 | — | — | — | ||

| Xenocyprisargentea | 49.90 | 19.80 | — | — | ||

| Cultrichthys erythropterus | — | 6.24 | — | — | ||

| Chaemrichthys stigmatias | — | 5.39 | — | — | ||

| Culter mongolicus | — | 38.16 | — | — | ||

| Mylopharyngodon piceus | — | 7.66 | — | — | ||

| Tridentiger trigonocephalus | — | 5.44 | 64.20 | — | ||

| Takifugu obscurus | — | 105.55 | 201.87 | 195.95 | ||

| Eleutheronema tetradactylum | — | 12.37 | 91.81 | — | ||

| Caranx sexfasciatus | — | 6.97 | — | — | ||

| hybrid sturgeon | — | — | 731.36 | — | ||

| Acipenser sinensis | 180.48 | — | — | — | ||

| Collichthys lucidus | — | — | 1862.76 | 920.72 | Aut. | |

| Miichthys miiuy | — | — | 490.56 | — | ||

| Acanthogobius ommaturus | — | — | 327.48 | — | ||

| Boleophthalmus pectinirostris | — | — | 20.52 | — | ||

| Season | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | 100.00% | |||

| Summer | 50.00% | 100.00% | ||

| Autumn | 31.71% | 37.50% | 100.00% | |

| Winter | 17.14% | 18.92% | 38.10% | 100.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, B.; Feng, G.; Gu, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Q. Seasonal Variation of Shoreline Fish Assemblages at Two Stations in the Southern Branch of the Yangtze River Estuary. Biology 2025, 14, 1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121785

Feng B, Feng G, Gu X, Yang J, Zhang Q. Seasonal Variation of Shoreline Fish Assemblages at Two Stations in the Southern Branch of the Yangtze River Estuary. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121785

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Bo, Guangpeng Feng, Xuzhe Gu, Ju Yang, and Qingbo Zhang. 2025. "Seasonal Variation of Shoreline Fish Assemblages at Two Stations in the Southern Branch of the Yangtze River Estuary" Biology 14, no. 12: 1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121785

APA StyleFeng, B., Feng, G., Gu, X., Yang, J., & Zhang, Q. (2025). Seasonal Variation of Shoreline Fish Assemblages at Two Stations in the Southern Branch of the Yangtze River Estuary. Biology, 14(12), 1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121785