Dinner Date: Opposite-Sex Pairs of Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) Forage More than Same-Sex Pairs

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Animals

2.2. Foraging Preference for Rich Versus Poor Patch Qualities

2.3. Social and Solitary Foraging Across Different Sex Pairings

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

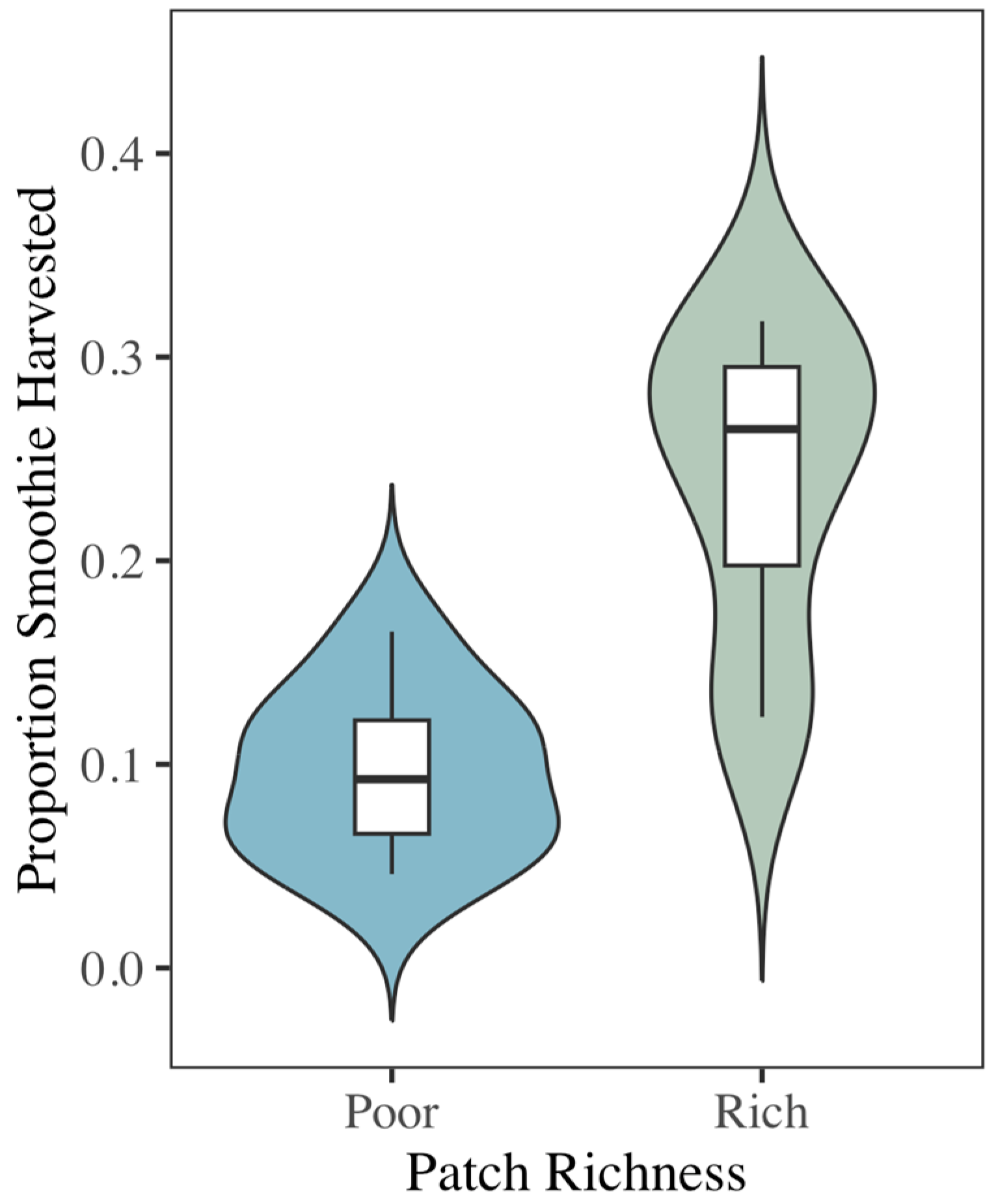

3.1. Egyptian Fruit Bats Prefer to Forage from Rich Food Patches

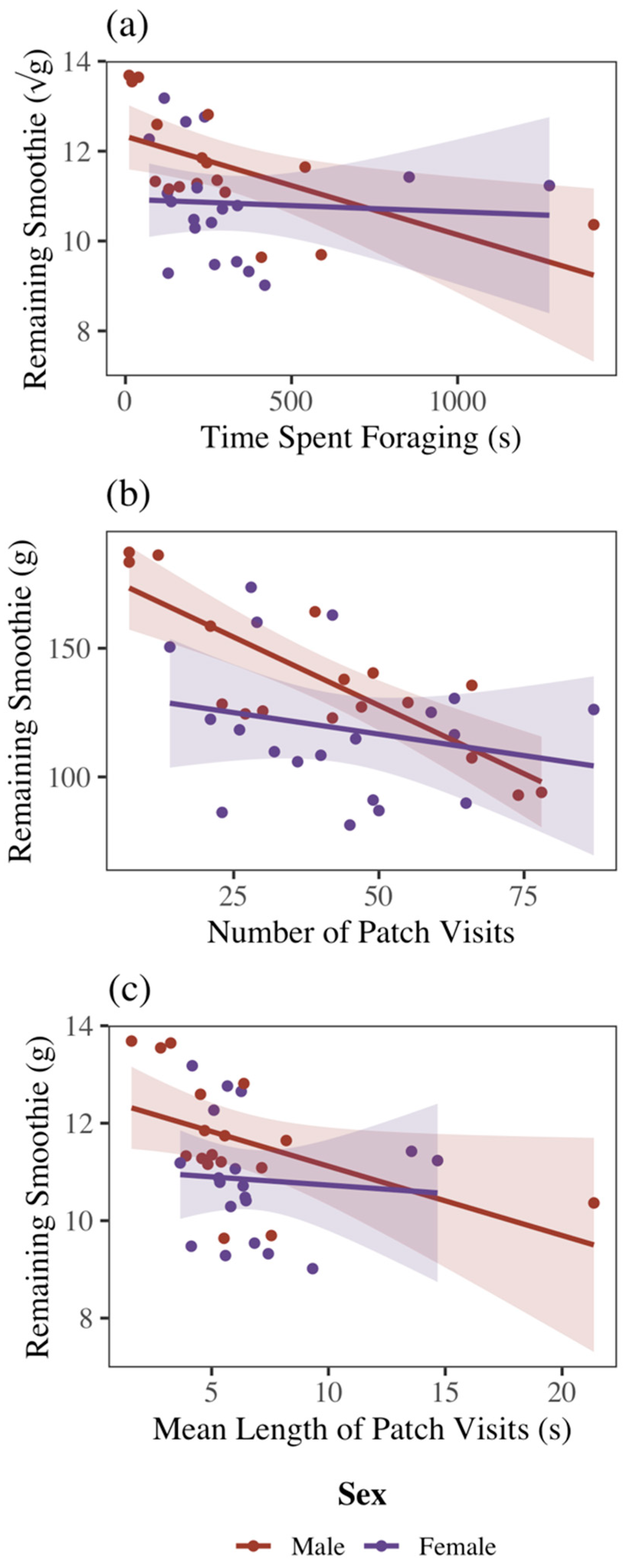

3.2. Sex and Foraging Metrics

3.3. Sex and Mass

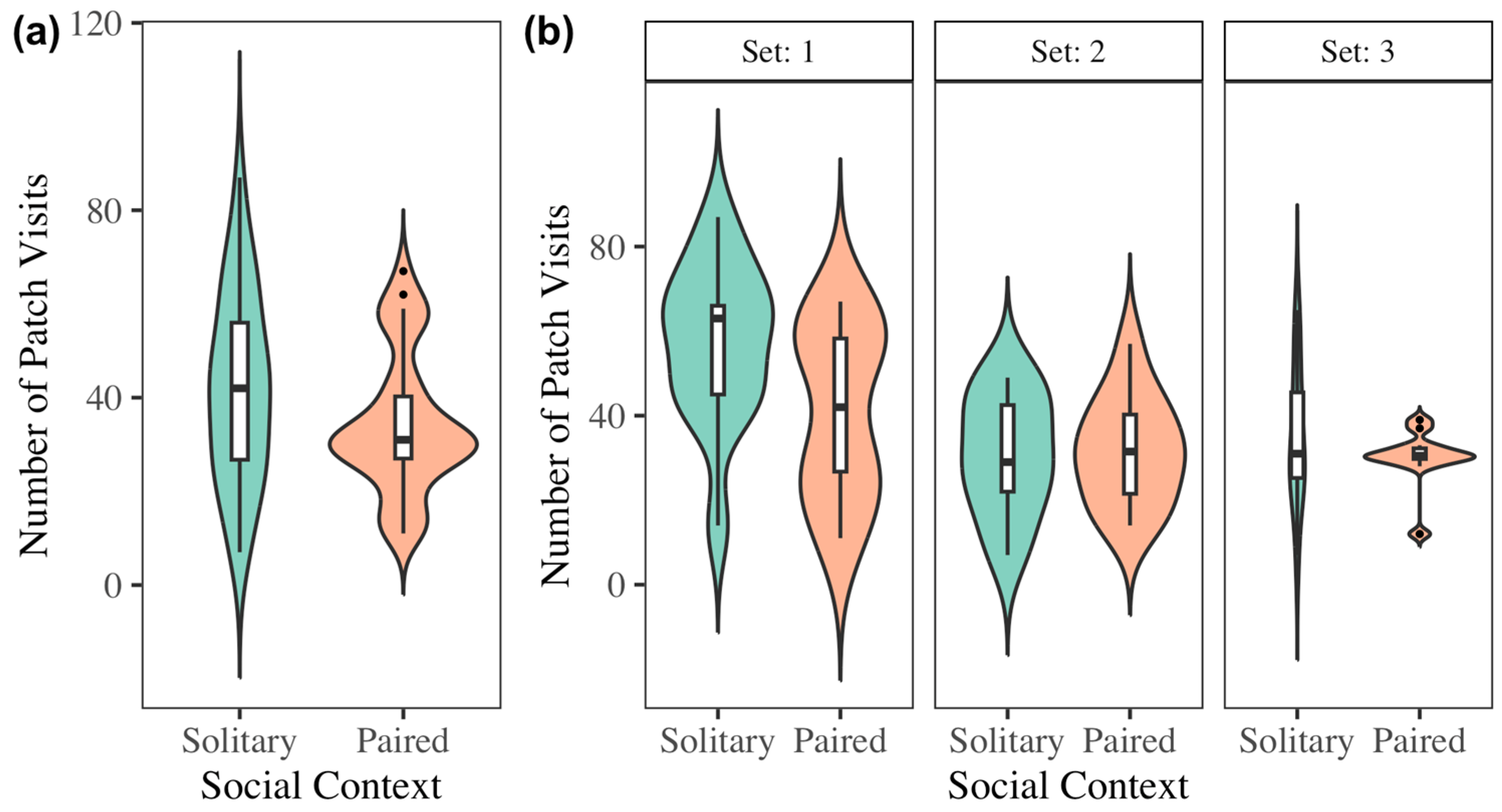

3.4. Solitary vs. Social Foraging

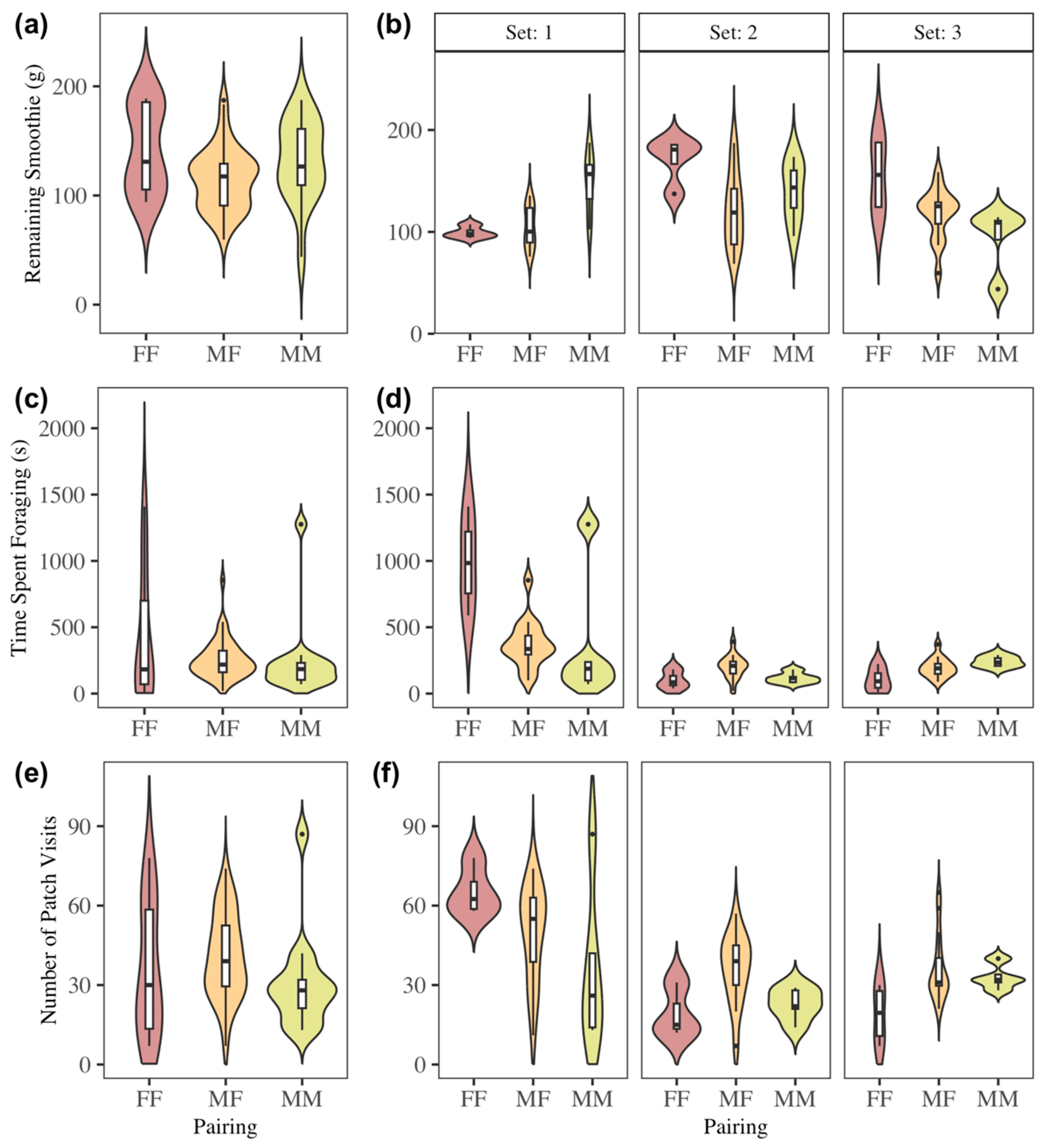

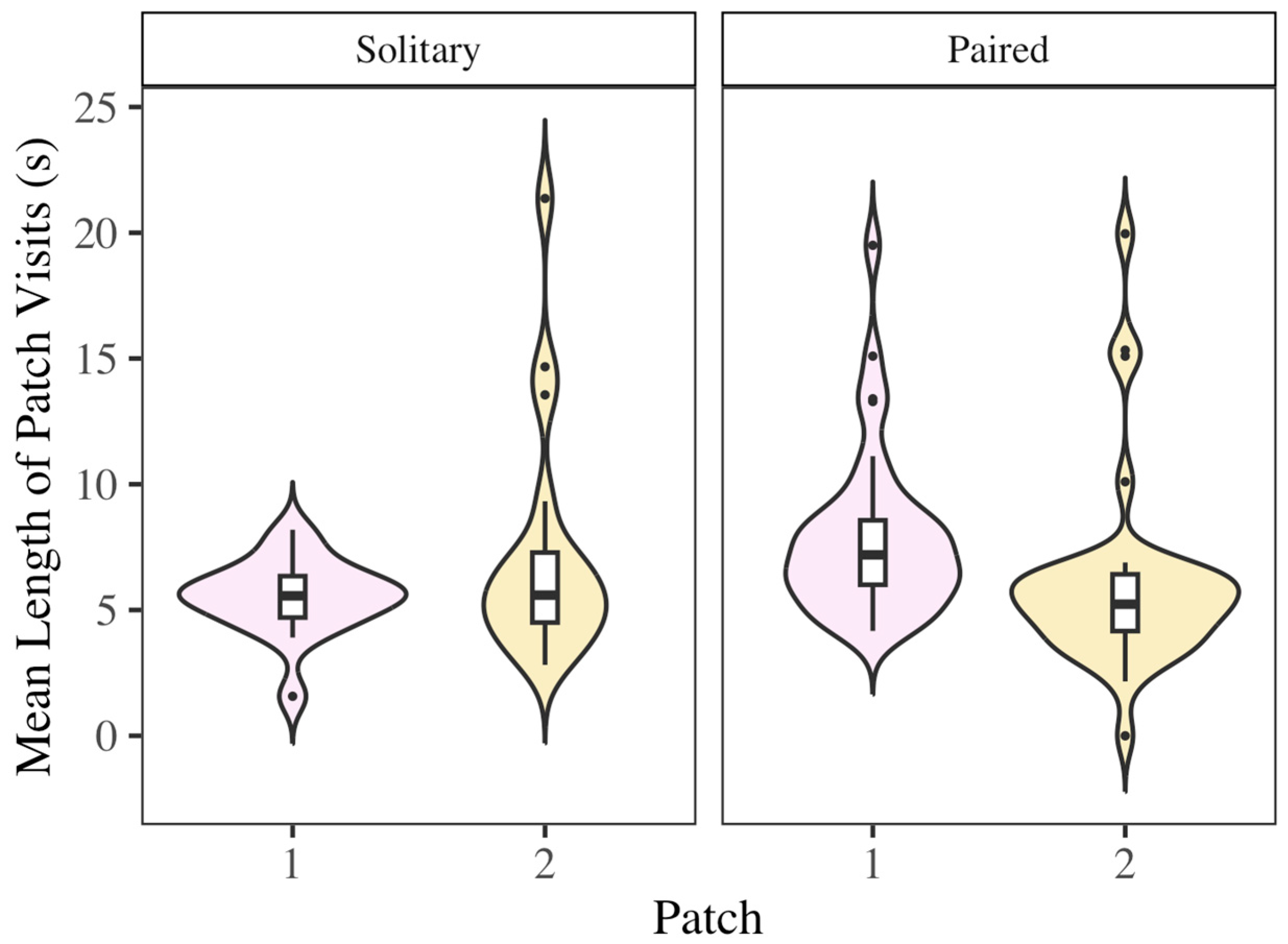

3.5. Effect of Pairing on Foraging

3.6. Patch Equity

3.7. Preference of Starting Patch

4. Discussion

4.1. Foraging Behavior and Strategies

4.2. Sex and Size Differences in Foraging

4.3. Foraging and Social Context

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, J.S. Patch Use as an Indicator of Habitat Preference, Predation Risk, and Competition. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1988, 22, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, Y.; Yovel, Y. Decision Making in Foraging Bats. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2020, 60, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.; Wilkinson, G. Does Food Sharing in Vampire Bats Demonstrate Reciprocity? Commun. Integr. Biol. 2013, 6, e25783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Boughman, J.W.; Wilkinson, G.S. Greater Spear-Nosed Bats Discriminate Group Mates by Vocalizations. Anim. Behav. 1998, 55, 1717–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.G. Interpersonal Expectations as the Building Blocks of Social Cognition: An Interdependence Theory Perspective. Pers. Relatsh. 2002, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harten, L.; Prat, Y.; Ben Cohen, S.; Dor, R.; Yovel, Y. Food for Sex in Bats Revealed as Producer Males Reproduce with Scrounging Females. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 1895–1900.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, B.J.; Gownaris, N.J.; Heerhartz, S.M.; Monaco, C.J. Personality, Foraging Behavior and Specialization: Integrating Behavioral and Food Web Ecology at the Individual Level. Oecologia 2016, 182, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foraging Theory|Princeton University Press. Available online: https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691084428/foraging-theory (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Abu Baker, M.A.; Brown, J.S. Patch Area, Substrate Depth, and Richness Affect Giving-Up Densities: A Test with Mourning Doves and Cottontail Rabbits. Oikos 2009, 118, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, F. Harvest Rates and Patch-Use Strategy of Egyptian Fruit Bats in Artificial Food Patches. J. Mammal. 2006, 87, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, F.; Korine, C.; Kotler, B.P.; Pinshow, B. Ethanol Concentration in Food and Body Condition Affect Foraging Behavior in Egyptian Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus). Naturwissenschaften 2008, 95, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiecinski, G.; Griffiths, T. Rousettus Egyptiacus. Mamm. Species 1999, 611, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, O.; Lieberman, V.; Köhler, A.; Korine, C.; Hedworth, H.E.; Voigt-Heucke, S.L. Finding Your Friends at Densely Populated Roosting Places: Male Egyptian Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) Distinguish between Familiar and Unfamiliar Conspecifics. Acta Chiropterol. 2011, 13, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulzer, E. Untersuchungen über die biologie von flughunden der gattung Rousettus Gray. Z. Morphol. Oekologie Tiere 1958, 47, 374–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, K.R.; Weinberg, M.; Harten, L.; Salinas Ramos, V.B.; Herrera, M.L.G.; Czirják, G.Á.; Yovel, Y. Sick Bats Stay Home Alone: Fruit Bats Practice Social Distancing When Faced with an Immunological Challenge. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1505, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dechmann, D.K.N.; Heucke, S.L.; Giuggioli, L.; Safi, K.; Voigt, C.C.; Wikelski, M. Experimental Evidence for Group Hunting via Eavesdropping in Echolocating Bats. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2009, 276, 2721–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazima, I.; Sazima, M. Solitary and Group Foraging: Two Flower-Visiting Patterns of the Lesser Spear-Nosed Bat Phyllostomus Discolor. Biotropica 1977, 9, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijders, L.; Krause, S.; Tump, A.N.; Breuker, M.; Ortiz, C.; Rizzi, S.; Ramnarine, I.W.; Krause, J.; Kurvers, R.H.J.M. Causal Evidence for the Adaptive Benefits of Social Foraging in the Wild. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrader, A.M.; Kotler, B.P.; Brown, J.S.; Kerley, G.I.H. Providing Water for Goats in Arid Landscapes: Effects on Feeding Effort with Regard to Time Period, Herd Size and Secondary Compounds. Oikos 2008, 117, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthey, A.J.R.; Banks, P.B. Foraging in Groups Affects Giving-up Densities: Solo Foragers Quit Sooner. Oecologia 2015, 178, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinevitch, L.; Holroyd, S.L.; Barclay, R.M.R. Sex Differences in the Use of Daily Torpor and Foraging Time by Big Brown Bats (Eptesicus fuscus) during the Reproductive Season. J. Zool. 1995, 235, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, P.; Butlin, R.K.; Altringham, J.D. Sex and Segregation in Temperate Bats. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 272, 2467–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, J.; Manly, B.; Kerry, K.; Gardner, H.; Franchi, E.; Corsolini, S.; Focardi, S. Sex Differences in Adélie Penguin Foraging Strategies. Polar Biol. 1998, 20, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.C.; Barclay, R.M.R. Differences in the Foraging Behaviour of Male and Female Big Brown Bats (Eptesicus fuscus) during the Reproductive Period. Écoscience 1997, 4, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, C.A.; Iverson, S.J.; Bowen, W.D.; Blanchard, W. Sex Differences in Grey Seal Diet Reflect Seasonal Variation in Foraging Behaviour and Reproductive Expenditure: Evidence from Quantitative Fatty Acid Signature Analysis. J. Anim. Ecol. 2007, 76, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginnett, T.F.; Demment, M.W. Sex Differences in Giraffe Foraging Behavior at Two Spatial Scales. Oecologia 1997, 110, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokke, S. Sex Differences in Feeding-Patch Choice in a Megaherbivore: Elephants in Chobe National Park, Botswana. Can. J. Zool. 1999, 77, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, L.M. Sex Differences in Diet and Foraging Behavior in White-Faced Capuchins (Cebus capucinus). Int. J. Primatol. 1994, 15, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, R.M.R.; Jacobs, D.S. Differences in the Foraging Behaviour of Male and Female Egyptian Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus). Can. J. Zool. 2011, 89, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučan, R.K.; Bartonička, T.; Jedlička, P.; Řeřucha, Š.; Šálek, M.; Čížek, M.; Nicolaou, H.; Horáček, I. Spatial Activity and Feeding Ecology of the Endangered Northern Population of the Egyptian Fruit Bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus). J. Mammal. 2016, 97, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harten, L.; Matalon, Y.; Galli, N.; Navon, H.; Dor, R.; Yovel, Y. Persistent Producer-Scrounger Relationships in Bats. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, e1603293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Páez, C.; Sánchez, F. Harvest Rates and Foraging Strategy of Carollia Perspicillata (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) in an Artificial Food Patch. Behav. Processes 2018, 157, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnov, E.L. Optimal Foraging, the Marginal Value Theorem. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1976, 9, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DVR-Scan. Available online: https://dvr-scan.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Friard, O.; Gamba, M. BORIS: A Free, Versatile Open-Source Event-Logging Software for Video/Audio Coding and Live Observations. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R: What Is R? Available online: https://www.r-project.org/about.html (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Brooks, M.E.; Kristensen, K.; van Benthem, K.J.; Magnusson, A.; Berg, C.W.; Nielsen, A.; Skaug, H.J.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.M. glmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-Inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. R J. 2017, 9, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R: Add or Drop All Possible Single Terms to a Model. Available online: https://search.r-project.org/R/refmans/stats/html/add1.html (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Emmeans. Available online: https://rvlenth.github.io/emmeans/authors.html (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Holland, R.; Waters, D.A.; Rayner, J.M.V. Echolocation Signal Structure in the Megachiropteran Bat Rousettus aegyptiacus Geoffroy 1810. J. Exp. Biol. 2004, 207, 4361–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, O.; Brown, J.S.; Smith, H.G. Gain Curves in Depletable Food Patches: A Test of Five Models with European Starlings. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2001, 3, 285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, J.C. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-12-813251-7. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, K.R.; Stokes, C.J.; Gordon, I.J. When Foraging and Fear Meet: Using Foraging Hierarchies to Inform Assessments of Landscapes of Fear. Behav. Ecol. 2008, 19, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S.; Laundré, J.W.; Gurung, M. The Ecology of Fear: Optimal Foraging, Game Theory, and Trophic Interactions. J. Mammal. 1999, 80, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealey, B.A.; James, L.S.; Ryan, M.J.; Page, R.A. The Influence of Hunger and Sex on the Foraging Decisions of Frugivorous Bats. Behav. Ecol. 2025, 36, araf095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lik, M.; Samsonowicz, T.; Zielińska, E. Morphometrics in Movement Biomechanics of Egyptian Fruit Bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus). In Proceedings of the Book of Articles National Scientific Conference “Novel Trends of Polish Science 2018”, Zakopane, Poland, 6–7 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Korine, C.; Speakman, J.; Arad, Z. Reproductive Energetics of Captive and Free-Ranging Egyptian Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus). Ecology 2004, 85, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.; Mackay, A.; Tollit, D.; Enderby, S.; Hammond, P. The Influence of Body Size and Sex on the Characteristics of Harbour Seal Foraging Trips. Can. J. Zool. 1998, 76, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, K.A. Field Metabolic Rate and Food Requirement Scaling in Mammals and Birds. Ecol. Monogr. 1987, 57, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, K. Field Bioenergetics of Mammals—What Determines Field Metabolic Rates. Aust. J. Zool. 1994, 42, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig-Straschil, B.; Robinson, G.A. On the Ecology of the Fruit Bat, Rousettus aegyptiacus Leachi (A. Smith, 1829) in the Tsitsikama Coastal National Park. Koedoe 1978, 21, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, J. East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-226-43718-7. [Google Scholar]

- Templeton, C.N.; Philp, K.; Guillette, L.M.; Laland, K.N.; Benson-Amram, S. Sex and Pairing Status Impact How Zebra Finches Use Social Information in Foraging. Behav. Process. 2017, 139, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicca-Marques, J.C.; Garber, P.A. Use of Social and Ecological Information in Tamarin Foraging Decisions. Int. J. Primatol. 2005, 26, 1321–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Effect on GUDs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F Value | Pr(>F) | |

| Foraging time | |||||

| Sex | 1 | 6.39 | 6.39 | 4.71 | 0.04 |

| Foraging time | 1 | 5.64 | 5.64 | 4.16 | 0.04 |

| Sex: Foraging time | 1 | 2.96 | 2.96 | 2.18 | 0.15 |

| Residuals | 32 | 43.40 | 1.36 | ||

| Number of patch visits | |||||

| Sex | 1 | 3241.3 | 3241.3 | 6.05 | 0.02 |

| Visit number | 1 | 8075.2 | 8075.2 | 15.06 | <0.001 |

| Sex: Visit number | 1 | 1871 | 1871 | 3.49 | 0.07 |

| Residuals | 32 | 17,155.3 | 536.1 | ||

| Mean visit time | |||||

| Sex | 1 | 6.39 | 6.385 | 4.46 | 0.04 |

| Mean visit time | 1 | 4.98 | 4.98 | 3.47 | 0.07 |

| Sex: Mean visit time | 1 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 0.81 | 0.37 |

| Residuals | 32 | 45.86 | 1.43 | ||

| Response Variable | Model Type | Fixed Effects (Random Effects) | Statistics | Tukey Pairwise Comparisons | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foraging time (s) | GLMM | Social | LRT3 = 0.43, p = 0.514 | Set1-Set2 | z64 = 5.24, p < 0.001 |

| Pairing | LRT2 = 1.18, p = 0.555 | Set1-Set3 | z64 = 4.78, p < 0.001 | ||

| Set | LRT1 = 15.73, p < 0.001 | Set2-Set3 | z64 = −0.56, p = 0.841 | ||

| (Bat ID) | Var. < 0.001, Std.Dev < 0.001 | ||||

| Patch visit number | GLMM | Social | LRT3 = 4.14, p = 0.042 | Set1-Set2 | z64 = 2.66, p = 0.021 |

| Pairing | LRT2 = 7.98, p = 0.019 | Set1-Set3 | z64 = 2.36, p = 0.048 | ||

| Set | LRT1 = 6.42, p = 0.040 | Set2-Set3 | z64 = −0.33, p = 9.43 | ||

| (Bat ID) | Var. = 0.26, Std.Dev = 0.16 | FF-MF | z64 = −1.10, p = 0.512 | ||

| FF-MM | z64 = 1.09, p = 0.512 | ||||

| MF-MM | z64 = 2.66, p = 0.022 | ||||

| Mean visit time (s) | GLMM | Social | LRT3 = 1.08, p = 0.298 | Set1-Set2 | z64 = 5.68, p < 0.001 |

| Pairing | LRT2 = 8.69, p = 0.013 | Set1-Set3 | z64 = 4.88, p < 0.001 | ||

| Set | LRT1 = 16.34, p < 0.001 | Set2-Set3 | z64 = −0.98, p = 0.590 | ||

| (Bat ID) | Var. < 0.001, Std.Dev = 0.028 | FF-MF | z64 = −1.10, p = 0.512 | ||

| FF-MM | z64 = 1.09, p = 0.519 | ||||

| MF-MM | z64 = 2.66, p = 0.022 | ||||

| GUDs (g) | GLM | Social | LRT3 = 1.99, p = 0.159 | FF-MF | t70 = 2.65, p = 0.027 |

| Pairing | LRT2 = 7.77, p = 0.021 | FF-MM | t70 = 0.99, p = 0.587 | ||

| Set | LRT1 = 4.65, p = 0.098 | MF-MM | t70 = −1.64, p = 0.237 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pergams, A.; Haus, M.; Estrada, C.; Brown, J.; Salles, A. Dinner Date: Opposite-Sex Pairs of Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) Forage More than Same-Sex Pairs. Biology 2025, 14, 1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121742

Pergams A, Haus M, Estrada C, Brown J, Salles A. Dinner Date: Opposite-Sex Pairs of Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) Forage More than Same-Sex Pairs. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121742

Chicago/Turabian StylePergams, Alexander, Mara Haus, Cristina Estrada, Joel Brown, and Angeles Salles. 2025. "Dinner Date: Opposite-Sex Pairs of Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) Forage More than Same-Sex Pairs" Biology 14, no. 12: 1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121742

APA StylePergams, A., Haus, M., Estrada, C., Brown, J., & Salles, A. (2025). Dinner Date: Opposite-Sex Pairs of Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) Forage More than Same-Sex Pairs. Biology, 14(12), 1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121742