Wavelet Components of Photoplethysmography During Reactive Hyperemia: Absolute vs. Relative Metrics

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Technologies

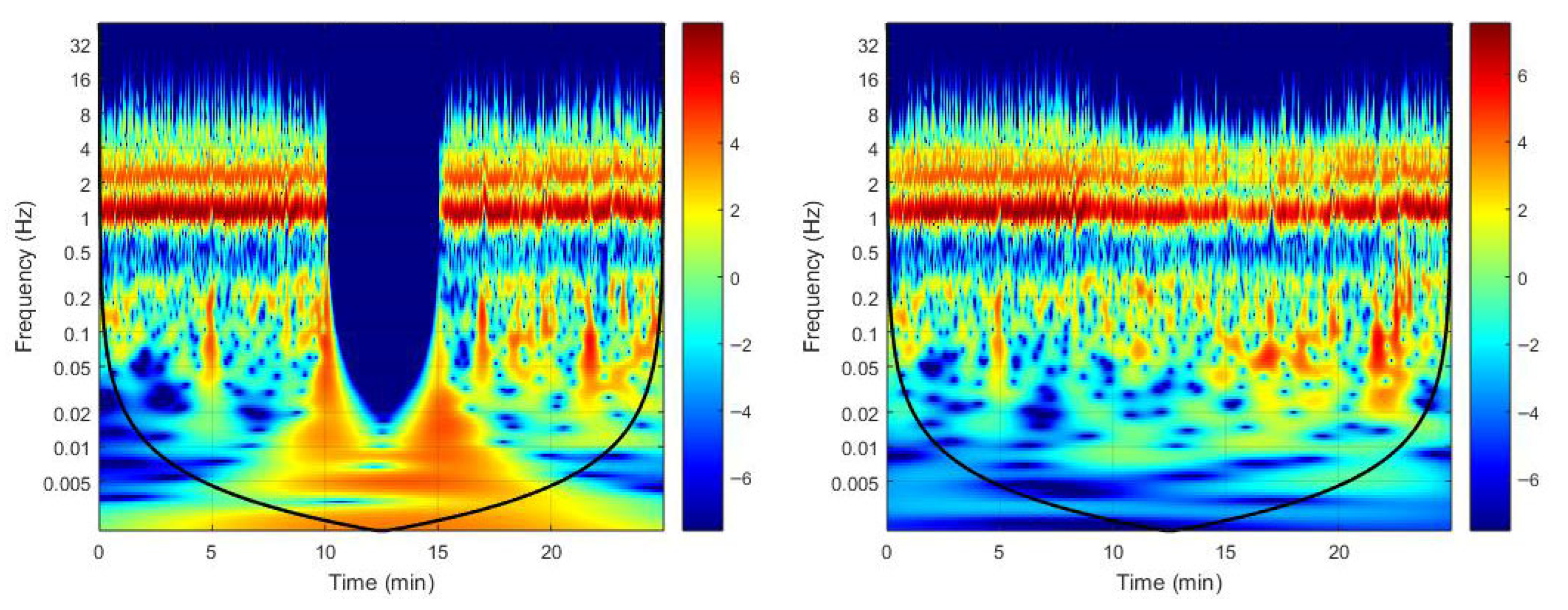

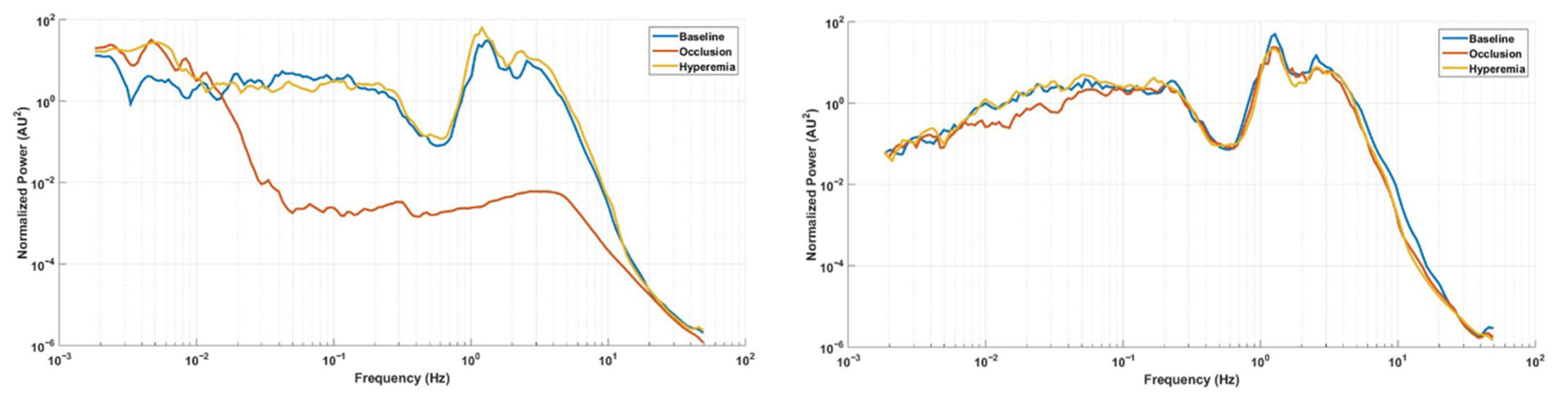

2.4. The Wavelet Transform

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, J.; Seok, H.S.; Kim, S.S.; Shin, H. Photoplethysmogram analysis and applications: An integrative review. Front. Physiol. 2022, 12, 808451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.; Rezendes, C.; Pinto, P.C. Enhancing the quantification of post-occlusive reactive hyperemia: A multimodal optical approach. Pflügers Arch. 2025, 477, 1213–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. Photoplethysmography and its application in clinical physiological measurement. Physiol. Meas. 2007, 28, R1–R39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieff, G.; Stone, K.; Paterson, C.; Fryer, S.; Diana, J.; Blackwell, J.; Meyer, M.L.; Stoner, L. Pulse-wave velocity assessments derived from a simple photoplethysmography device: Agreement with a referent device. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1108219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlton, P.H.; Allen, J.; Bailón, R.; Baker, S.; Behar, J.A.; Chen, F.; Clifford, G.D.; Clifton, D.A.; Davies, H.J.; Ding, C.; et al. The 2023 wearable photoplethysmography roadmap. Physiol. Meas. 2023, 44, 111001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.; Ferreira, H.A.; da Silva, H.P.; Monteiro Rodrigues, L. The venoarteriolar reflex significantly reduces contralateral perfusion as part of the lower limb circulatory homeostasis in vivo. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, E.; Orini, M.; Bailón, R.; Vergara, J.M.; Mainardi, L.; Laguna, P. Photoplethysmography pulse rate variability as a surrogate measurement of heart rate variability during non-stationary conditions. Physiol. Meas. 2010, 31, 1271–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultman, M.; Richter, F.; Larsson, M.; Strömberg, T.; Iredahl, F.; Fredriksson, I. Robust analysis of microcirculatory flowmotion during post-occlusive reactive hyperemia. Microvasc. Res. 2024, 155, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralj, L.; Hultman, M.; Lenasi, H. Wavelet analysis and the cone of influence: Does the cone of influence impact wavelet analysis results? Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.; Šorli, J.; Lenasi, H. Oral glucose load and human cutaneous microcirculation: An insight into flowmotion assessed by wavelet transform. Biology 2021, 10, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralj, L.; Battelino, T.; Lenasi, H. Effects of oral glucose tolerance test on microvascular and autonomic nervous system regulation in young healthy individuals. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralj, L.; Potocnik, N.; Lenasi, H. Evaluating transient phenomena by wavelet analysis: Early recovery to exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2024, 326, H96–H102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovska, A.; Bračič, M. Physics of the human cardiovascular system. Contemp. Phys. 1999, 40, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvernmo, H.D.; Stefanovska, A.; Kirkebøen, K.A.; Kvernebo, K. Oscillations in the human cutaneous blood perfusion signal modified by endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent vasodilators. Microvasc. Res. 1999, 57, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Rosei, E.A.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; De Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L.Z.H.; Wu, L.C.; Wang, J.H. Continuous wavelet transform analysis of acceleration signals measured from a wave buoy. Sensors 2013, 13, 10908–10930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvandal, P.; Landsverk, S.A.; Bernjak, A.; Stefanovska, A.; Kvernmo, H.D.; Kirkebøen, K.A. Low-frequency oscillations of the laser Doppler perfusion signal in human skin. Microvasc. Res. 2006, 72, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, H.; Rocha, C.; Monteiro Rodrigues, L. Combining laser-doppler flowmetry and photoplethysmography to explore in vivo vascular physiology. J. Biomed. Biopharm. Res. 2016, 13, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.M.; Rocha, C.; Ferreira, H.; Silva, H. Different lasers reveal different skin microcirculatory flowmotion: Data from the wavelet transform analysis of human hindlimb perfusion. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, H.; Bento, M.; Vieira, H.; Monteiro Rodrigues, L. Comparing the spectral components of laser Doppler flowmetry and photoplethysmography signals for the assessment of the vascular response to hyperoxia. J. Biomed. Biopharm. Res. 2017, 14, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.M.; Rocha, C.; Ferreira, H.T.; Silva, H.N. Lower limb massage in humans increases local perfusion and impacts systemic hemodynamics. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 128, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizeva, I.; Di Maria, C.; Frick, P.; Podtaev, S.; Allen, J. Quantifying the correlation between photoplethysmography and laser Doppler flowmetry microvascular low-frequency oscillations. J. Biomed. Opt. 2015, 20, 037007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovska, A.; Poǩorný, J. Correlation integral and frequency analysis of cardiovascular functions. Physiol. Meas. 1997, 4, 457–478. [Google Scholar]

- Mück-Weymann, M.E.; Albrecht, H.P.; Hager, D.; Hiller, D.; Hornstein, O.P.; Bauer, R.D. Respiratory-dependent laser-Doppler flux motion in different skin areas and its meaning to autonomic nervous control of the vessels of the skin. Microvasc. Res. 1996, 52, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.U.; Borgström, P.; Lindbom, L.; Intaglietta, M. Vasomotion patterns in skeletal muscle arterioles during changes in arterial pressure. Microvasc. Res. 1988, 35, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastrup, J.; Bülow, J. Vasomotion in human skin before and after local heating recorded with laser Doppler flowmetry: A method for induction of vasomotion. Int. J. Microcirc. 1989, 8, 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Söderström, T.; Stefanovska, A.; Veber, M.; Svensson, H. Involvement of sympathetic nerve activity in skin blood flow oscillations in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003, 284, H1638–H1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golenhofen, K. Slow rhythms in smooth muscle. In Smooth Muscle; Bülbring, E., Brading, A.F., Jones, A.W., Tomita, T., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1970; pp. 316–342. [Google Scholar]

- Tankanag, A.; Krasnikov, G.; Mizeva, I. A pilot study: Wavelet cross-correlation of cardiovascular oscillations under controlled respiration in humans. Microvasc. Res. 2020, 130, 103993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsverk, S.A.; Kvandal, P.; Kjelstrup, T.; Benko, U.; Bernjak, A.; Stefanovska, A.; Kvernmo, H.; Kirkeboen, K.A. Human skin microcirculation after brachial plexus block evaluated by wavelet transform of the laser Doppler flowmetry signal. Anesthesiology 2006, 105, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.; Garcia, T.; Aniqa, M.; Ali, S.; Ally, A.; Nauli, S.M. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and the cardiovascular system: In physiology and in disease states. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. Res. 2022, 15, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, A.; Pal, M.; Intaglietta, M.; Johnson, P.C. Contribution of anaerobic metabolism to reactive hyperemia in skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 292, H2643–H2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roddie, I.C. Circulation to skin and adipose tissue. In Handbook of Physiology; The Cardiovascular System, Vol. II, Part 1; Shepard, J.T., Abboud, F.M., Eds.; American Physiological Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1983; pp. 285–317. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, S.; Minson, C.T. Human cutaneous reactive hyperaemia: Role of BKCa channels and sensory nerves. J. Physiol. 2007, 585, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarr, G.W.; Cheung, S.S. Effects of sensory nerve blockade on cutaneous microvascular responses to ischemia–reperfusion injury. Microvasc. Res. 2022, 144, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.J. Perspective: Physiological role(s) of the vascular myogenic response. Microcirculation 2012, 19, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernick, D.P.; Tooke, J.E.; Shore, A.C. The biological zero signal in laser Doppler fluximetry: Origins and practical implications. Pflügers Arch.–Eur. J. Physiol. 1999, 437, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.; Ferreira, H.; Rodrigues, L.M. Studying the oscillatory components of human skin microcirculation. In Agache’s Measuring the Skin: Non-Invasive Investigations, Physiology, Normal Constants, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 569–582. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.M.; Kellogg, D.L. Local thermal control of the human cutaneous circulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 109, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tipton, M.J.; Harper, A.; Paton, J.F.R.; Costello, J.T. The human ventilatory response to stress: Rate or depth? J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 5729–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynès, C.; Perez-Martin, A.; Ennaifer, H.; Silva, H.; Knapp, Y.; Vinet, A. Mechanisms of venoarteriolar reflex in type 2 diabetes with or without peripheral neuropathy. Biology 2021, 10, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.F.; Hsiu, H.; Sung, C.J.; Lee, C.H. Combining laser-Doppler flowmetry measurements with spectral analysis to study different microcirculatory effects in human prediabetic and diabetic subjects. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorovich, A.A.; Loktionova, Y.I.; Zharkikh, E.V.; Gorshkov, A.Y.; Korolev, A.I.; Dadaeva, V.A.; Drapkina, O.M.; Zherebtsov, E.A. Skin microcirculation in middle-aged men with newly diagnosed arterial hypertension according to remote laser Doppler flowmetry data. Microvasc. Res. 2022, 144, 104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, Y.K.; Struck, B.D.; Foreman, R.D.; Robinson, C. Wavelet analysis of sacral skin blood flow oscillations to assess soft tissue viability in older adults. Microvasc. Res. 2009, 78, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Age (years) | 21.6 ± 1.9 | 21.2 ± 1.2 | 22.0 ± 2.4 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.3 ± 4.2 | 21.8 ± 2.8 | 24.6 ± 5.0 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 115.2 ± 8.4 | 118.0 ± 4.5 | 112.8 ± 10.5 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76.2 ± 8.9 | 73.0 ± 8.6 | 78.2 ± 9.5 |

| Fasting period (h) | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 3.3 ± 0.1 |

| Menstrual cycle duration (days) | - | - | 29 ± 1 |

| Menstrual cycle day | - | - | 5 ± 2 |

| Component | Test (T) | Contralateral (C) | p-Value (T vs. C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin blood flow (AU) | Baseline | 443.4 (37.3; 781.1) | 461.5 (49.5; 759.7) | 0.155 |

| Occlusion | 12.9 (6.3; 63.3) | 456.9 (62.9; 724.8) | 0.003 * | |

| Hyperemia | 508.9 (172.9; 735.8) | 495.8 (59.4; 672.9) | 0.041 * | |

| ΔII-I (%) | −96.4 (−99.2; −5.2) | −8.0 (−48.6; 59.6) | 0.002 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.003 * | 0.006 * | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.084 | 0.366 | - | |

| Cardiac | Baseline | 1.1 × 1011 (2.3 × 109; 9.1 × 1011) | 1.6 × 1011 (2.9 × 109; 6.1 × 1011) | 0.308 |

| Occlusion | 2.1 × 107 (3.5 × 106; 2.3 × 109) | 1.2 × 1011 (3.6 × 109; 4.9 × 1011) | 0.002 * | |

| Hyperemia | 1.4 × 1011 (2.7 × 1010; 7.6 × 1011) | 1.5 × 1011 (4.8 × 109; 3.6 × 1011) | 0.041 * | |

| ΔII-I (%) | −100% (−100; 55) | −46% (−82; 510) | 0.002 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.003 * | 0.071 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.638 | 0.049 * | - | |

| Respiratory | Baseline | 1.1 × 1010 (8.5 × 108; 4.6 × 1010) | 1.5 × 1010 (2.0 × 109; 2.3 × 1010) | 0.433 |

| Occlusion | 1.0 × 107 (3.7 × 106; 3.5 × 109) | 1.1 × 1010 (1.2 × 109; 4.6 × 1010) | 0.002 * | |

| Hyperemia | 1.9 × 1010 (5.2 × 109; 4.1 × 1010) | 1.6 × 1010 (2.9 × 109; 7.4 × 1010) | 0.875 | |

| ΔII-I (%) | −100% (−100; 57) | −26% (−51; 130) | 0.023 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.005 * | 0.638 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.041 * | 0.433 | - | |

| Myogenic | Baseline | 3.0 × 1010 (3.3 × 109; 7.6 × 1010) | 2.7 × 1010 (3.6 × 109; 9.1 × 1010) | 0.530 |

| Occlusion | 8.0 × 106 (2.4 × 106; 2.6 × 109) | 2.3 × 1010 (7.0 × 109; 5.1 × 1010) | 0.002 * | |

| Hyperemia | 2.5 × 1010 (8.1 × 109; 1.3 × 1011) | 3.1 × 1010 (5.2 × 109; 1.2 × 1011) | 0.937 | |

| ΔII-I (%) | −100% (−100; −41) | −25% (−72; 392) | 0.005 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.002 * | 0.099 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.060 | 0.638 | - | |

| Neurogenic | Baseline | 2.6 × 1010 (1.8 × 109; 7.2 × 1010) | 3.0 × 1010 (2.0 × 109; 5.6 × 1010) | 0.638 |

| Occlusion | 6.7 × 108 (1.4 × 108; 1.2 × 1010) | 7.3 × 109 (2.7 × 109; 4.8 × 1010) | 0.012 * | |

| Hyperemia | 2.1 × 1010 (2.1 × 1010; 3.0 × 109) | 2.9 × 1010 (2.8 × 109; 9.5 × 1010) | 0.638 | |

| ΔII-I (%) | −98% (−100; 864) | −39% (−82; 333) | 0.034 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.008 * | 0.049 * | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.209 | 0.480 | - | |

| Endothelial NO-dependent | Baseline | 1.2 × 1010 (2.9 × 109; 3.0 × 1010) | 6.9 × 109 (1.5 × 109; 2.8 × 1010) | 0.060 |

| Occlusion | 1.5 × 1010 (5.7 × 109; 2.9 × 1010) | 4.0 × 109 (9.8 × 108; 1.9 × 1010) | 0.015 * | |

| Hyperemia | 2.5 × 1010 (3.9 × 1010; 5.5 × 1010) | 1.2 × 1010 (8.7 × 108; 4.1 × 1010) | 0.023 * | |

| ΔII-I (%) | 9% (−72; 1124) | −46% (−84; 90) | 0.182 | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.480 | 0.071 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.019 * | 0.308 | - | |

| Endothelial NO-independent | Baseline | 1.1 × 1010 (3.1 × 109; 2.5 × 1010) | 2.4 × 109 (3.3 × 108; 7.7 × 109) | 0.002 * |

| Occlusion | 4.7 × 1010 (1.8 × 1010; 7.9 × 1010) | 2.0 × 109 (3.6 × 108; 4.2 × 109) | 0.002 * | |

| Hyperemia | 4.6 × 1010 (5.2 × 109; 8.9 × 1010) | 2.2 × 109 (2.2 × 108; 1.1 × 1010) | 0.002 * | |

| ΔII-I (%) | 293% (36; 2266) | −13% (−75; 59) | 0.002 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.002 * | 0.084 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.010 * | 0.754 | - | |

| Component | Test (T) | Contralateral (C) | p-Value (T vs. C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | Baseline | 58.6 (3.4; 87.8) | 63.0 (5.6; 85.9) | 0.195 |

| Occlusion | 0.0 (0.0; 1.5) | 58.9 (6.6; 91.0) | 0.002 * | |

| Hyperemia | 58.7 (14.8; 84.1) | 51.8 (5.8; 80.8) | 0.182 | |

| ΔII-I (%) | −100 (−100; −76) | −16 (−42; 186) | 0.002 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.002 * | 0.530 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.724 | 0.308 | - | |

| Respiratory | Baseline | 3.9 (1.3; 12.8) | 5.5 (2.0; 13.0) | 0.125 |

| Occlusion | 0.0 (0.0; 2.4) | 7.8 (2.1; 20.4) | 0.002 * | |

| Hyperemia | 4.1 (2.1; 10.6) | 6.5 (2.6; 20.8) | 0.031 * | |

| ΔII-I (%) | −99 (−100; −64) | 21 (−61; 282) | 0.002 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.002 * | 0.065 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.875 | 0.060 | - | |

| Myogenic | Baseline | 13.2 (3.4; 33.3) | 11.2 (2.7; 36.8) | 0.894 |

| Occlusion | 0.0 (0.0; 2.1) | 15.0 (4.1; 37.1) | 0.002 * | |

| Hyperemia | 9.9 (3.4; 30.1) | 14.1 (6.2; 43.3) | 0.008 * | |

| ΔII-I (%) | −100 (−100; −84) | 33 (−54; 147) | 0.002 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.002 * | 0.182 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.255 | 0.308 | - | |

| Neurogenic | Baseline | 10.7 (0.8; 36.6) | 7.4 (1.4; 36.4) | 0.722 |

| Occlusion | 0.8 (0.5; 9.2) | 8.4 (1.0; 33.7) | 0.010 * | |

| Hyperemia | 6 (1; 32) | 13.7 (4.5; 35.1) | 0.019 * | |

| ΔII-I (%) | −88.2 (−98.3; 180.4) | 7 (−76; 101) | 0.049 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.014 * | 0.937 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.195 | 0.239 | - | |

| Endothelial NO-dependent | Baseline | 5.5 (1.0; 27.2) | 2.1 (0.4; 39.6) | 0.158 |

| Occlusion | 21.4 (15.5; 25.9) | 1.7 (0.5; 21.3) | 0.004 * | |

| Hyperemia | 6.2 (1.1; 16.7) | 4.2 (1.9; 26.0) | 0.937 | |

| ΔII-I (%) | 343 (−27; 1810) | −14 (−84; 225) | 0.006 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.010 * | 0.388 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.754 | 0.209 | - | |

| Endothelial NO-independent | Baseline | 4.3 (1.8; 24.6) | 1.1 (0.2; 13.7) | 0.002 * |

| Occlusion | 77.6 (59.8; 82.0) | 1.1 (0.2; 10.6) | 0.002 * | |

| Hyperemia | 12.6 (1.3; 44.7) | 0.8 (0.2; 12.3) | 0.002 * | |

| ΔII-I (%) | 1759 (286; 4397) | 2 (−75; 340) | 0.002 * | |

| p-value (II vs. I) | 0.002 * | 0.753 | - | |

| p-value (III vs. I) | 0.012 * | 0.814 | - | |

| Correlation | Test Limb | Contralateral Limb |

|---|---|---|

| Δ cardiac % vs. Δ cardiac power | 0.839 (0.001 *) | 0.930 (<0.001 *) |

| Δ respiratory % vs. Δ respiratory power | 0.943 (<0.001 *) | 0.413 (0.183) |

| Δ myogenic % vs. Δ myogenic power | 0.828 (0.001 *) | 0.720 (0.008 *) |

| Δ neurogenic % vs. Δ neurogenic power | 0.816 (0.001 *) | 0.490 (0.106) |

| Δ endothelial NOd % vs. Δ endothelial NOd power | 0.217 (0.499) | 0.637 (0.026 *) |

| Δ endothelial NOi % vs. Δ endothelial NOi power | −0.357 (0.255) | 0.678 (0.015 *) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, H.; Lavrador, N. Wavelet Components of Photoplethysmography During Reactive Hyperemia: Absolute vs. Relative Metrics. Biology 2025, 14, 1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121727

Silva H, Lavrador N. Wavelet Components of Photoplethysmography During Reactive Hyperemia: Absolute vs. Relative Metrics. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121727

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Henrique, and Nicole Lavrador. 2025. "Wavelet Components of Photoplethysmography During Reactive Hyperemia: Absolute vs. Relative Metrics" Biology 14, no. 12: 1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121727

APA StyleSilva, H., & Lavrador, N. (2025). Wavelet Components of Photoplethysmography During Reactive Hyperemia: Absolute vs. Relative Metrics. Biology, 14(12), 1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121727