Light, Dyes, and Action: Photodynamic Inactivation of Leishmania amazonensis Using Methylene Blue, New Methylene Blue, and Novel Ruthenium-Based Derivatives

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compounds and Parasite Culture

2.2. Photodynamic Inhibition Assay

2.3. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

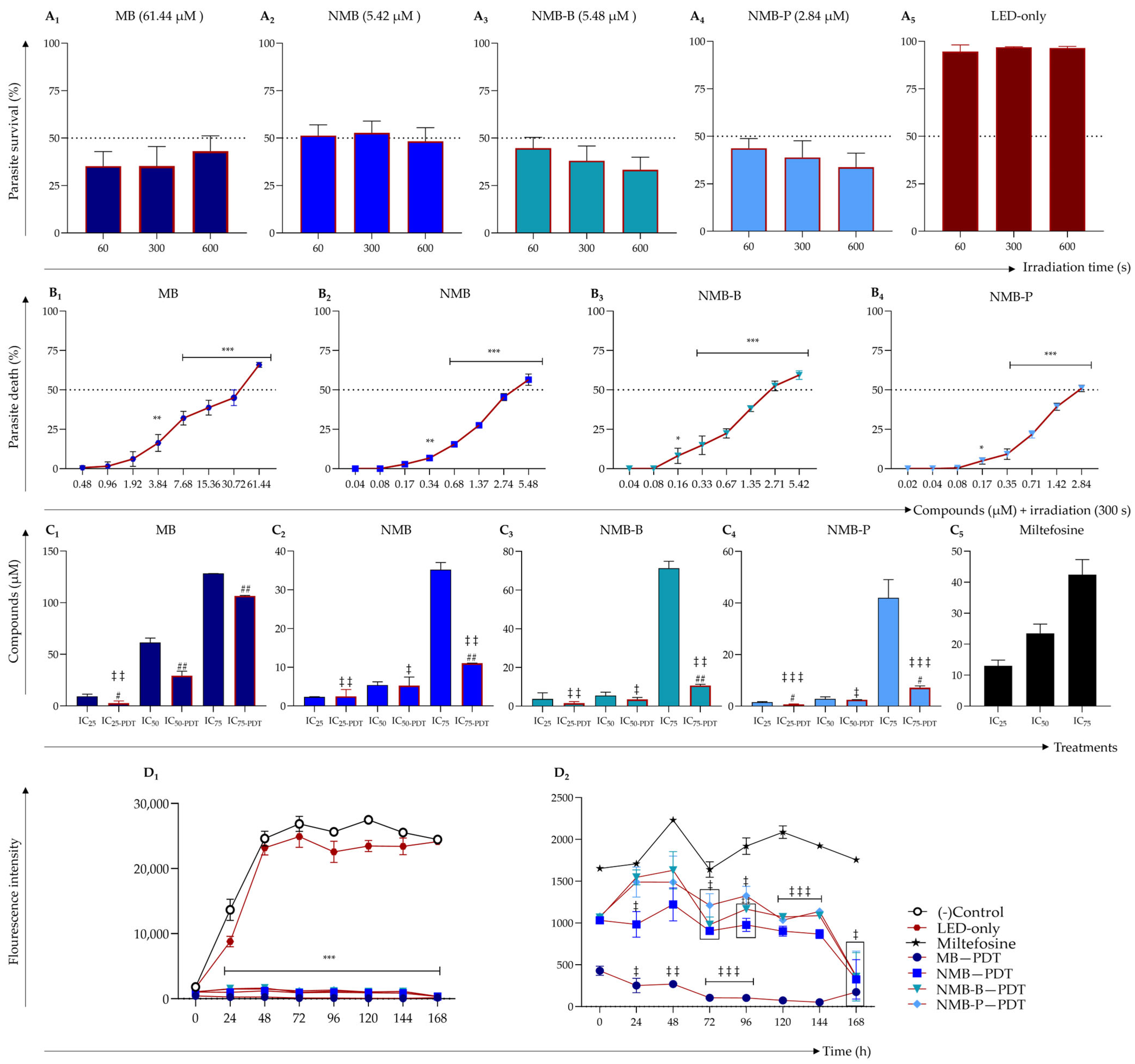

3.1. Photodynamic Therapy Enhances Antileishmanial Efficacy of Tested Dyes

3.2. Dyes Activated by PDT Outperform Miltefosine in Sustained Leishmanicidal Activity

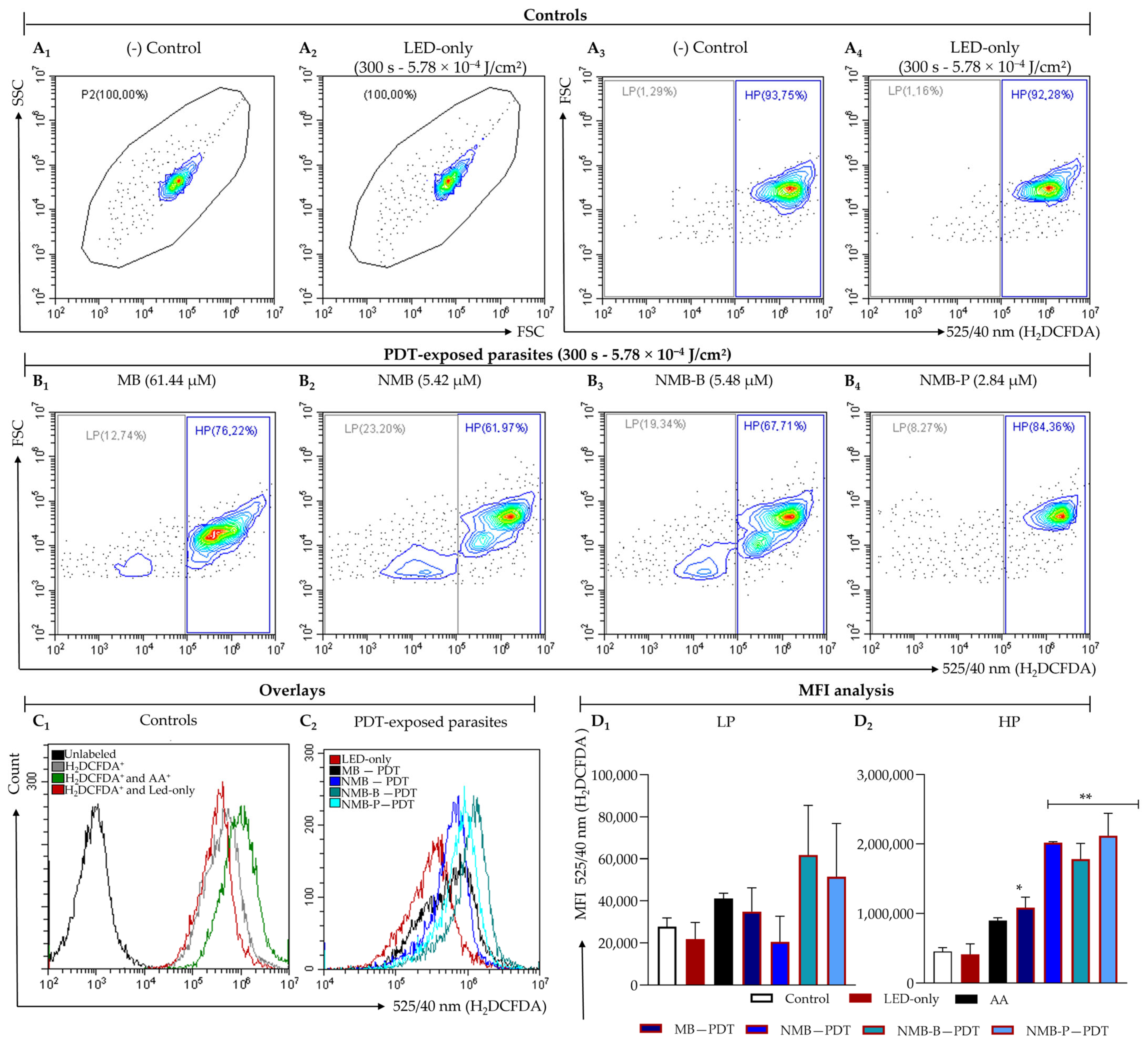

3.3. Ruthenium-Based Photosensitizers Boost ROS Generation

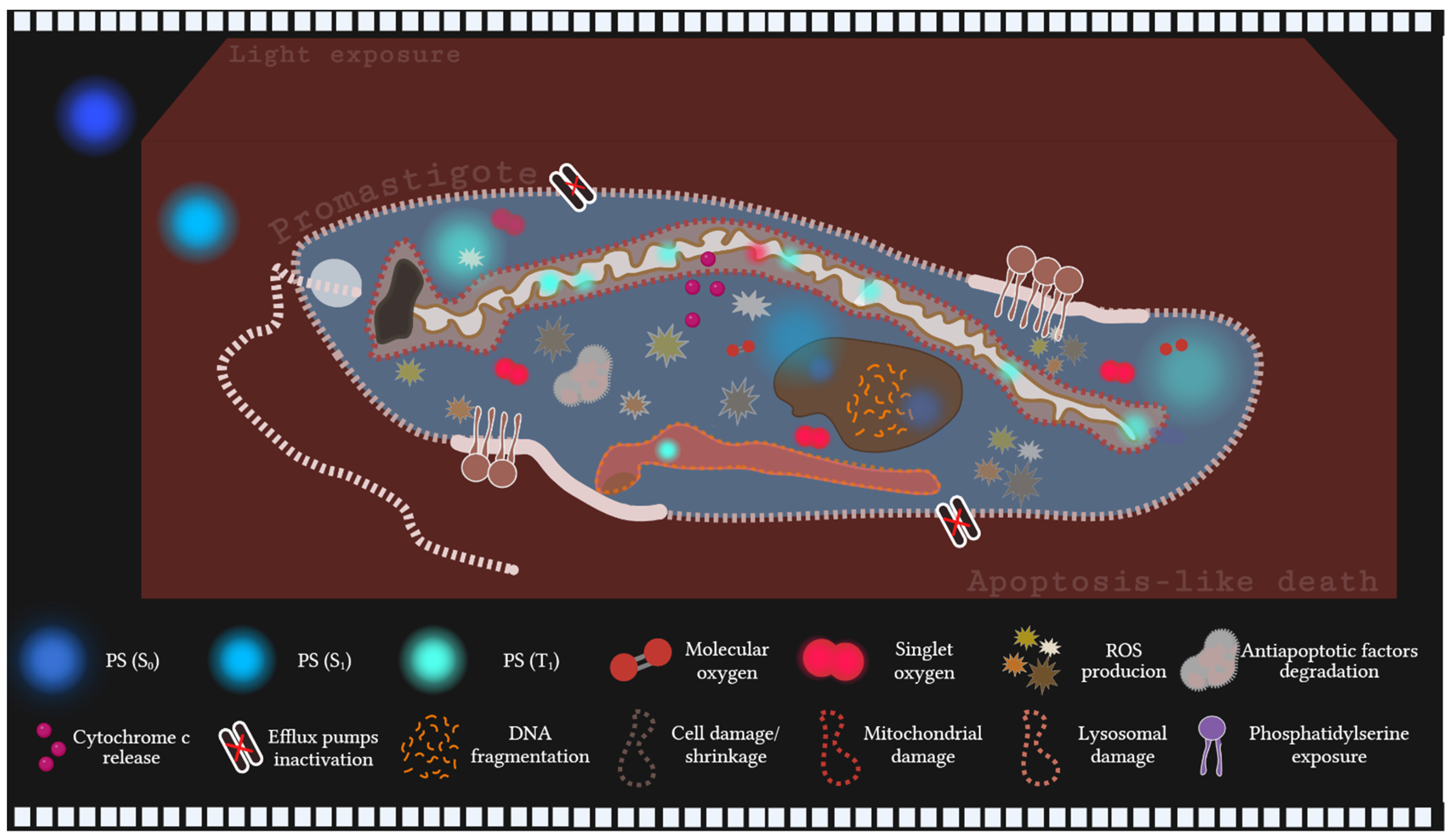

3.4. Photodynamic Therapy Triggers Extensive Cell Death in Leishmania

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Antimycin A |

| AV | Annexin V |

| CL | Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

| DAPI | 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DMBB | 1,9-Dimethyl-methylene blue |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| H2DCFDA | 2,7-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| HP | High population |

| IC25 | 25% Inhibitory concentration |

| IC50 | 50% Maximal inhibitory concentration |

| IC75 | 75% Inhibitory concentration |

| LED | Light-emitting diode |

| LP | Low population |

| MB | Methylene blue |

| MFI | Median fluorescence intensity |

| NMB | New methylene blue |

| NMB-B | New methylene blue B |

| NMB-P | New methylene blue P |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDT | Photodynamic therapy |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| PS | Photosensitizer |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Sb(III) | Trivalent antimony |

| Sb(V) | Pentavalent antimonials |

| VIROS | Variation index of ROS production |

References

- Winau, F.; Westphal, O.; Winau, R. Paul Ehrlich—In Search of the Magic Bullet. Microbes Infect. 2004, 6, 786–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strebhardt, K.; Ullrich, A. Paul Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet Concept: 100 Years of Progress. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vennerstrom, J.L.; Makler, M.T.; Angerhofer, C.K.; Williams, J.A. Antimalarial Dyes Revisited: Xanthenes, Azines, Oxazines, and Thiazines. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 2671–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sörgel, F. The Return of Ehrlich’s ‘Therapia Magna Sterilisans’ and Other Ehrlich Concepts? Chemotherapy 2004, 50, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gensini, G.F.; Conti, A.A.; Lippi, D. The Contributions of Paul Ehrlich to Infectious Disease. J. Infect. 2007, 54, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruta, H. From Chemotherapy to Signal Therapy (1909–2009): A Century Pioneered by Paul Ehrlich. Drug Discov. Ther. 2009, 3, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asif, M. Uses of Diazo Dyes as Drugs. J. Adv. Res. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 1, 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Vianna, G. Sobre o Tratamento da Leishmaniose Tegumentar. Ann. Paul. Med. Cir. 1914, 2, 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Rezende, J.M. Gaspar Vianna, Mártir da Ciência e Benfeitor da Humanidade. In À Sombra do Plátano: Crônicas de História da Medicina; Editora Fap-Unifesp: São Paulo, Brazil, 2009; pp. 359–362. ISBN 9788561673635. [Google Scholar]

- Frézard, F.; Demicheli, C.; Ribeiro, R.R. Pentavalent Antimonials: New Perspectives for Old Drugs. Molecules 2009, 14, 2317–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, A.S.; Pita, S.S.R.; Guimarães, E.T. Tratamento da Leishmaniose, Limitações da Terapêutica Atual e a Necessidade de Novas Alternativas: Uma Revisão Narrativa. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e29510716543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, M.M.; Cuervo, G.; Martín, E.M.; Las Heras, M.V.; Pérez, J.P.; Yélamos, S.M.; Fernández, N.S. Neurological Toxicity Due to Antimonial Treatment for Refractory Visceral Leishmaniasis. Clin. Neurophysiol. Pract. 2021, 6, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, V.R.; Jesus, L.C.L.; Soares, R.-E.P.; Silva, L.D.M.; Pinto, B.A.S.; Melo, M.N.; Paes, A.M.A.; Pereira, S.R.F. Meglumine Antimoniate (Glucantime) Causes Oxidative Stress-Derived DNA Damage in BALB/c Mice Infected by Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, C.C.J.; Torraca, T.S.d.S.; Bezerra, D.d.O.; Leite, N.K.S.; Oliveira, R.d.V.C.d.; Araújo-Melo, M.H.; Pimentel, M.I.F.; da Costa, A.D.; Vasconcellos, É.d.C.F.; Lyra, M.R.; et al. Self-Reporting of Hearing Loss and Tinnitus in the Diagnosis of Ototoxicity by Meglumine Antimoniate in Patients Treated for American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyra, M.R.; Passos, S.R.L.; Pimentel, M.I.F.; Pacheco, S.J.B.; Rosalino, C.M.V.; Vasconcellos, E.C.F.; Antonio, L.F.; Saheki, M.N.; Salguiro, M.M.; Santos, G.P.L.; et al. Pancreatic Toxicity as an Adverse Effect Induced by Meglumine Antimoniate. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2016, 58, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.C.; Morais-Teixeira, E.; Reis, P.G.; Silva-Barcellos, N.M.; Salaün, P.; Campos, P.P.; Dias Corrêa-Junior, J.; Rabello, A.; Demicheli, C.; Frézard, F. Hepatotoxicity of Pentavalent Antimonial Drug: Possible Role of Residual Sb(III) and Protective Effect of Ascorbic Acid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, K.A.; Abdalla, I.O.; Alkailani, H.A.; Elbakush, A.M.; Zreiba, Z.A. Evaluation of Hepatotoxicity Effect of Sodium Stibogluconate (Pentostam) in Mice Model. Al-Mukhtar J. Sci. 2022, 37, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Luo, C.; Zheng, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Ding, W.; Shen, Z.; Xue, P.; Yu, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. TRPML1 Contributes to Antimony-Induced Nephrotoxicity by Initiating Ferroptosis via Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 184, 114378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, J.M.; García-Martínez, C.E.; Saldarriaga, C.; Pérez, G.E.; Barbosa de Melo, M.; Wyss, F.; Sosa-Liprandi, Á.; Ortiz-Lopez, H.I.; Gupta, S.; López-Santi, R.; et al. Leishmaniasis y Corazón. Arch. Cardiol. México 2021, 92, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijal, S.; Chappuis, F.; Singh, R.; Boelaert, M.; Loutan, L.; Koirala, S. Sodium Stibogluconate Cardiotoxicity and Safety of Generics. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 97, 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopke, L.F.F.; Café, M.E.M.; Neves, L.B.; Scherrer, M.A.R.; Machado Pinto, J.; Souza, M.S.L.A.; Vale, E.S.; Andrade, A.R.C.; Figueiredo, J.O.P.; Silva, R.A.N.P. Morte Após Uso de Antimonial Pentavalente em Leishmaniose Tegumentar Americana. An. Bras. Dermatol. 1993, 68, 259–261. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M.C.; Amorim, R.F.B.; Freitas, R.A.; Costa, A.L.L. Óbito em Caso de Leishmaniose Cutâneomucosa Após o Uso de Antimonial Pentavalente. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2005, 38, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Oliveira, L.F.; Schubach, A.O.; Martins, M.M.; Passos, S.L.; Oliveira, R.V.; Marzochi, M.C.; Andrade, C.A. Systematic Review of the Adverse Effects of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Treatment in the New World. Acta Trop. 2011, 118, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponte-Sucre, A.; Gamarro, F.; Dujardin, J.-C.; Barrett, M.P.; López-Vélez, R.; García-Hernández, R.; Pountain, A.W.; Mwenechanya, R.; Papadopoulou, B. Drug Resistance and Treatment Failure in Leishmaniasis: A 21st Century Challenge. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0006052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, S.A.; Merlotto, M.R.; Ramos, P.M.; Marques, M.E.A. American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis: Severe Side Effects of Pentavalent Antimonial in a Patient with Chronic Renal Failure. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2019, 94, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periferakis, A.; Caruntu, A.; Periferakis, A.-T.; Scheau, A.-E.; Badarau, I.A.; Caruntu, C.; Scheau, C. Availability, Toxicology and Medical Significance of Antimony. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vries, H.J.C.; Schallig, H.D. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A 2022 Updated Narrative Review into Diagnosis and Management Developments. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis: Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- OPAS, Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde. Plano de Ação Para Fortalecer a Vigilância e o Controle Das Leishmanioses Nas Américas 2023–2030; OPAS, Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; ISBN 9789275728789. [Google Scholar]

- PAHO, Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Leishmaniasis: Epidemiological Report on the Regeion of the Americas; PAHO, Organización Panamericana de la Salud: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yizengaw, E.; Nibret, E. Effects of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis on Patients’ Quality of Life. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merdekios, B.; Shewangizaw, M.; Sappo, A.; Ewunetu, E.; van Griensven, J.; van geertruyden, J.P.; Ceuterick, M.; Bastiaens, H. Unveiling the Hidden Burden: Exploring the Psychosocial Impact of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Lesions and Scars in Southern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuwangi, H.; Agampodi, T.C.; Price, H.P.; Shepherd, T.; Weerakoon, K.G.; Agampodi, S.B. Stigma Associated with Cutaneous and Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DNDi, Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative. From Neglect to Hope: Voices of Leishmaniasis. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yt8fNz73N8s&t=236s (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- DNDi, Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative. The Mark of Neglect: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRtx2N2YR2k&t=2s (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- DNDi, Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative. Pip Stewart on Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: ‘It Wasn’t Just the Parasite That Got under My Skin, It Was the Injustice of It’. Available online: https://dndi.org/stories/2021/pip-stewart-on-cutaneous-leishmaniasis/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Pip, S. Leishmaniasis: A Love Letter to a Flesh Eating Parasite [Video]. TED. Available online: https://www.ted.com/talks/pip_stewart_leishmaniasis_a_love_letter_to_a_flesh_eating_parasite_jan_2019 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Roatt, B.M.; Cardoso, J.M.O.; Brito, R.C.F.; Coura-Vital, W.; Aguiar-Soares, R.D.O.; Reis, A.B. Recent Advances and New Strategies on Leishmaniasis Treatment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8965–8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasidharan, S.; Saudagar, P. Leishmaniasis: Where Are We and Where Are We Heading? Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shmueli, M.; Ben-Shimol, S. Review of Leishmaniasis Treatment: Can We See the Forest Through the Trees? Pharmacy 2024, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okwor, I.; Uzonna, J. Social and Economic Burden of Human Leishmaniasis. Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya-Salazar, J.; Pasco, I.A.; Cañari, B.; Contreras-Pulache, H. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Associated with the Level of Poverty of the Andean Rural Population: A Five-Year Single-Center Study. Electron. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 18, em335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grifferty, G.; Shirley, H.; McGloin, J.; Kahn, J.; Orriols, A.; Wamai, R. Vulnerabilities to and the Socioeconomic and Psychosocial Impacts of the Leishmaniases: A Review. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 2021, 12, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brustolin, A.Á.; Ramos-Milaré, Á.C.F.H.; Castro, K.R.; Mota, C.A.; Pelloso, S.M.; Silveira, T.G.V. Successful Combined Therapy with GlucantimeTM and Pentoxifylline for the Nasal Mucosal Lesion Recently Developed in a Leishmaniasis Patient Having Untreated Cutaneous Lesion for Seven Decades. Parasitol. Int. 2021, 85, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, N.R.D.L.P.; Fialho, S.N.; Gouveia, A.J.; Ferreira, A.S.; Silva, M.A.; Martinez, L.N.; Nascimento, W.S.P.; Gonzaga, A., Jr.; Medeiros, D.S.S.; Barros, N.B.; et al. Quinine and Chloroquine: Potential Preclinical Candidates for the Treatment of Tegumentary Leishmaniasis. Acta Trop. 2024, 252, 107143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowari, P.; Roy, S.; Das, S.; Chowdhuri, S.; Kushwaha, R.; Das, B.K.; Ukil, A.; Das, D. Mannose-Decorated Composite Peptide Hydrogel with Thixotropic and Syneresis Properties and Its Application in Treatment of Leishmaniasis. Chem. Asian J. 2022, 17, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berhe, H.; Sridhar, M.K.C.; Zerihun, M.; Qvit, N. The Potential Use of Peptides in the Fight Against Chagas Disease and Leishmaniasis. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari, M.; Oryan, A.; Hatam, G. Immunotherapy in Treatment of Leishmaniasis. Immunol. Lett. 2021, 233, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taslimi, Y.; Zahedigadr, F.; Rafati, S. Leishmaniasis and Various Immunotherapeutic Approaches. Parasitology 2018, 145, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, S.; Trahamane, E.J.O.; Monteiro, J.; Santos, G.P.; Crugeira, P.; Sampaio, F.; Oliveira, C.; Neto, M.B.; Pinheiro, A. Leishmanicidal Effect of Antiparasitic Photodynamic Therapy—ApPDT on Infected Macrophages. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1959–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Bartolomeo, L.; Altavilla, D.; Vaccaro, M.; Vaccaro, F.; Squadrito, V.; Squadrito, F.; Borgia, F. Photodynamic Therapy in Pediatric Age: Current Applications and Future Trends. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 879380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, J.H.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Pimenta, S.; Dong, T.; Yang, Z. Photodynamic Therapy Review: Principles, Photosensitizers, Applications, and Future Directions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Q.; Li, N. Photodynamic Therapies: Basic Mechanism, Applications and Functional Nanomaterial-Based Drug Delivery System for Cancer. In Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)—Principles, Mechanisms and Applications; Fitzgerald, F., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–34. ISBN 978-1-53611-9329. [Google Scholar]

- Alamon-Reig, F.; Martí-Martí, I.; Loughlin, C.R.-M.; Garcia, A.; Carrera, C.; Aguilera-Peiró, P. Successful Treatment of Facial Cutaneous Leishmaniasis with Photodynamic Therapy. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2022, 88, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomi, F.L.; Peterle, L.; Vaccaro, M.; Borgia, F. Daylight Photodynamic Therapy for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in a Pediatric Setting: A Case Report and Literature Review. Photo. Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 44, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardivo, J.P.; Del Giglio, A.; Oliveira, C.S.; Gabrielli, D.S.; Junqueira, H.C.; Tada, D.B.; Severino, D.; Turchiello, R.F.; Baptista, M.S. Methylene Blue in Photodynamic Therapy: From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Photo. Photodyn. Ther. 2005, 2, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, J.G.; Martins, J.F.S.; Pereira, A.H.C.; Mittmann, J.; Raniero, L.J.; Ferreira-Strixino, J. Evaluation of Methylene Blue as Photosensitizer in Promastigotes of Leishmania major and Leishmania braziliensis. Photo. Photodyn. Ther. 2017, 18, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardozo, A.P.M.; Silva, D.F.T.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Ferreira, R.C.; Lino-dos-Santos-Franco, A.; Rodrigues, M.F.S.D.; Motta, L.J.; Cecatto, R.B. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy with Methylene Blue and Its Derivatives in Animal Studies: Systematic Review. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2024, 40, e12978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakirski, G.; Lehmann, P.; Szeimies, R.; Hofmann, S.C. Photodynamic Therapy in Dermatology: Established and New Indications. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 2024, 22, 1651–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelgrims, J.; De Vos, F.; Van den Brande, J.; Schrijvers, D.; Prové, A.; Vermorken, J.B. Methylene Blue in the Treatment and Prevention of Ifosfamide-Induced Encephalopathy: Report of 12 Cases and a Review of the Literature. Br. J. Cancer 2000, 82, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teichert, M.C.; Jones, J.W.; Usacheva, M.N.; Biel, M.A. Treatment of Oral Candidiasis with Methylene Blue-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy in an Immunodeficient Murine Model. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2002, 93, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberdi, E.; Gómez, C. Successful Treatment of Pityriasis Versicolor by Photodynamic Therapy Mediated by Methylene Blue. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2020, 36, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, T.H.S.; Gomes, J.M.S.; Alacoque, M.; Vannier-Santos, M.A.; Gomes, M.A.; Busatti, H.G.N.O. Transmission Electron Microscopy Revealing the Mechanism of Action of Photodynamic Therapy on Trichomonas vaginalis. Acta Trop. 2019, 190, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gironés, N.; Bueno, J.L.; Carrión, J.; Fresno, M.; Castro, E. The Efficacy of Photochemical Treatment with Methylene Blue and Light for the Reduction of Trypanosoma cruzi in Infected Plasma. Vox Sang. 2006, 91, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, F.V.; Sabino, C.P.; Dimmer, J.A.; Sauter, I.P.; Cortez, M.J.; Ribeiro, M.S. Preclinical Investigation of Methylene Blue-Mediated Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy on Leishmania Parasites Using Real-Time Bioluminescence. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peloi, L.S.; Biondo, C.E.G.; Kimura, E.; Politi, M.J.; Lonardoni, M.V.C.; Aristides, S.M.A.; Dorea, R.C.C.; Hioka, N.; Silveira, T.G.V. Photodynamic Therapy for American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: The Efficacy of Methylene Blue in Hamsters Experimentally Infected with Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 128, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.; Lindoso, J.A.L.; Oyafuso, L.K.; Kanashiro, E.H.Y.; Cardoso, J.L.; Uchoa, A.F.; Tardivo, J.P.; Baptista, M.S. Photodynamic Therapy Using Methylene Blue to Treat Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2011, 29, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, N.; Poojari, T.; Poojary, C.; Sande, R.; Sawant, S. Drug Repurposing: A Shortcut to New Biological Entities. Pharm. Chem. J. 2022, 56, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasco-dos-santos, D.R.; Almeida-silva, J.; Fiuza, L.F.A.; Vacani-Martins, N.; Rocha, Z.N.; Soeiro, M.N.C.; Henrique-Pons, A.; Torres-Santos, E.C.; Vannier-Santos, M.A. From Dyes to Drugs? Selective Leishmanicidal Efficacy of Repositioned Methylene Blue and Its Derivatives In Vitro Evaluation. Biology, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Aureliano, D.P.; Lindoso, J.A.L.; Soares, S.R.C.; Takakura, C.F.H.; Pereira, T.M.; Ribeiro, M.S. Cell Death Mechanisms in Leishmania amazonensis Triggered by Methylene Blue-Mediated Antiparasitic Photodynamic Therapy. Photo. Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, F.V.; Riahi, M.; Persheyev, S.; Lian, C.; Cortez, M.; Samuel, I.D.W.; Ribeiro, M.S. Photodynamic Therapy Offers a Novel Approach to Managing Miltefosine-Resistant Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 116881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Nagarajan, A.; Uchil, P.D. Analysis of Cell Viability by the Alamar Blue Assay. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2018, 2018, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniell, M.D.; Hill, J.S. A History of Photodynamic Therapy. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1991, 61, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessel, D. Photodynamic Therapy: A Brief History. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackroyd, R.; Kelty, C.; Brown, N.; Reed, M. The History of Photodetection and Photodynamic Therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001, 74, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stájer, A.; Kajári, S.; Gajdács, M.; Musah-Eroje, A.; Baráth, Z. Utility of Photodynamic Therapy in Dentistry: Current Concepts. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spikes, J.D. The Origin and Meaning of the Term “Photodynamic” (as Used in “Photodynamic Therapy”, for Example). J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1991, 9, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bergh, H. Photodynamic Therapy of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: History and Principles. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2001, 16, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taldaev, A.; Terekhov, R.; Nikitin, I.; Melnik, E.; Kuzina, V.; Klochko, M.; Reshetov, I.; Shiryaev, A.; Loschenov, V.; Ramenskaya, G. Methylene Blue in Anticancer Photodynamic Therapy: Systematic Review of Preclinical Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1264961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostinis, P.; Berg, K.; Cengel, K.A.; Foster, T.H.; Girotti, A.W.; Gollnick, S.O.; Hahn, S.M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Juzeniene, A.; Kessel, D.; et al. Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer: An Update. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 250–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, K.A.; Nelen, M.I.; Simard, T.P.; Davies, S.R.; Gollnick, S.O.; Oseroff, A.R.; Gibson, S.L.; Hilf, R.; Chen, L.B.; Detty, M.R. Synthesis and Evaluation of Chalcogenopyrylium Dyes as Potential Sensitizers for the Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 3953–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Xu, C.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Wu, M.; Xue, F. Vehicle-Free Nanotheranostic Self-Sssembled from Clinically Approved Dyes for Cancer Fluorescence Imaging and Photothermal/Photodynamic Combinational Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamblin, M.R. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Inactivation: A Bright New Technique to Kill Resistant Microbes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016, 33, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, T.; Gayathri, M.P.; Mack, J.; Nyokong, T.; Govindarajan, S.; Babu, B. Blue-Light-Activated Water-Soluble Sn(Iv)-Porphyrins for Antibacterial Photodynamic Therapy (APDT) against Drug-Resistant Bacterial Pathogens. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 2365–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzavara-Pinton, P.; Rossi, M.T.; Sala, R.; Venturini, M. Photodynamic Antifungal Chemotherapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 2012, 88, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enwemeka, C.S.; Baker, T.L.; Greiner, J.V.; Bumah, V.V.; Masson-Meyers, D.S.; Castel, J.C.; Vesonder, M. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy as a Potential Treatment against COVID-19: A Case for Blue Light. Photo. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 577–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, S.K.; Leung, A.W.N.; Xu, C. Photodynamic Action of Curcumin and Methylene Blue against Bacteria and SARS-CoV-2—A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, N.; Gerola, A.P.; Novello, C.R.; Ueda-Nakamura, T.; Silva, S.O.; Dias-Filho, B.P.; Hioka, N.; Mello, J.C.P.; Nakamura, C.V. Pheophorbide a, a Compound Isolated from the Leaves of Arrabidaea chica, Induces Photodynamic Inactivation of Trypanosoma cruzi. Photo. Photodyn. Ther. 2017, 19, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, N.; Sagar, M.; Abidin, Z.U.; Naeem, M.A.; Din, S.Z.U.; Ahmad, I. Photodynamic Therapy in Management of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Systematic Review. Lasers Med. Sci. 2024, 39, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbeghen, M.R.; Voltarelli, E.M.; Campois, T.G.; Kimura, E.; Aristides, S.M.A.; Hernandes, L.; Caetano, W.; Hioka, N.; Lonardoni, M.V.C.; Silveira, T.G.V. Topical and Intradermal Efficacy of Photodynamic Therapy with Methylene Blue and Light-Emitting Diode in the Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania braziliensis. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 6, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, R.A.F.N.; Navasconi, T.R.; Reis, V.N.; Hioka, N.; Becker, T.C.A.; Lonardoni, M.V.C.; Aristides, S.M.A.; Silveira, T.G.V. Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment of American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis: Evaluation of Therapies Association in Experimentally Infected Mice with Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 9, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vital-Fujii, D.G.; Baptista, M.S. Progress in the Photodynamic Therapy Treatment of Leishmaniasis. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2021, 54, e11570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, F.V.; Cerone, M.; Persheyev, S.; Lian, C.; Samuel, I.D.W.; Ribeiro, M.S.; Smith, T.K. New Insights in Photodynamic Inactivation of Leishmania amazonensis: A Focus on Lipidomics and Resistance. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varzandeh, M.; Mohammadinejad, R.; Esmaeilzadeh-Salestani, K.; Dehshahri, A.; Zarrabi, A.; Aghaei-Afshar, A. Photodynamic Therapy for Leishmaniasis: Recent Advances and Future Trends. Photo. Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 36, 102609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.C.; Sun, H.; Guo, D.S. Type I Photodynamic Therapy by Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Materials: From Strategies to Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 395, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Liao, K.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, T.; Quan, G.; Pan, X.; Wu, C. Application of Glutathione Depletion in Cancer Therapy: Enhanced ROS-Based Therapy, Ferroptosis, and Chemotherapy. Biomaterials 2021, 277, 121110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougherty, T.J. Introduction. In Photodynamic Therapy—Methods and Protocols; Gomer, C.J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–33. ISBN 9781607616962. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Jesus, V.P.S.; Raniero, L.; Lemes, G.M.; Bhattacharjee, T.T.; Caetano Júnior, P.C.; Castilho, M.L. Nanoparticles of Methylene Blue Enhance Photodynamic Therapy. Photo. Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 23, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidalgo, L.M.; Gille, L. Mitochondria and Trypanosomatids: Targets and Drugs. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 2758–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannavaram, S.; Debrabant, A. Programmed Cell Death in Leishmania: Biochemical Evidence and Role in Parasite Infectivity. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awashi, B.P.; Majhi, S.; Mitra, K. Oxidative Stress Inducers as Potential Anti-Leishmanial Agents. In Oxidative Stress in Microbial Diseases; Chakraborti, S., Chakraborti, T., Chattopadhyay, D., Shaha, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 539–566. ISBN 9789811387630. [Google Scholar]

- Menna-Barreto, R.F.S. Cell Death Pathways in Pathogenic Trypanosomatids: Lessons of (over) Kill. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannier-Santos, M.; De Castro, S. Electron Microscopy in Antiparasitic Chemotherapy: A (Close) View to a Kill. Curr. Drug Targets 2009, 10, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozlem-Caliskan, S.; Ertabaklar, H.; Bilgin, M.D.; Ertug, S. Evaluation of Photodynamic Therapy against Leishmania tropica Promastigotes Using Different Photosensitizers. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2022, 38, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Ruiz, A.; Alzate, J.F.; MacLeod, E.T.; Lüder, C.G.K.; Fasel, N.; Hurd, H. Apoptotic Markers in Protozoan Parasites. Parasites Vectors 2010, 3, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proto, W.R.; Coombs, G.H.; Mottram, J.C. Cell Death in Parasitic Protozoa: Regulated or Incidental? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimenta, P.F.P.; Dos Santos, M.A.V.; De Souza, W. Fine Structure and Cytochemistry of the Interaction between Leishmania mexicana amazonensis and Rat Neutrophils and Eosinophils. J. Submicrosc. Cytol. 1987, 19, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Zhou, X.; Pang, J.; Yang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Yin, R. New Methylene Blue-Mediated Photodynamic Inactivation of Multidrug-Resistant Fonsecaea nubica Infected Chromoblastomycosis In Vitro. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portapilla, G.B.; Pereira, L.M.; Costa, C.M.B.; Providello, M.V.; Oliveira, P.A.S.; Goulart, A.; Anchieta, N.F.; Wainwright, M.; Braga, G.Ú.L.; Albuquerque, S. Phenothiazinium Dyes Are Active against Trypanosoma cruzi In Vitro. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 8301569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragàs, X.; Dai, T.; Tegos, G.P.; Agut, M.; Nonell, S.; Hamblin, M.R. Photodynamic Inactivation of Acinetobacter baumannii Using Phenothiazinium Dyes: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Lasers Surg. Med. 2010, 42, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nery, R.L.A.; Santos, T.M.S.; Gois, L.L.; Barral, A.; Khouri, R.; Feitosa, C.A.; Santos, L.A. Leishmania spp. Genetic Factors Associated with Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Antimony Pentavalent Drug Resistance: A Systematic Review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2024, 119, e230240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, M.B.R.; Miranda, G.O.; Carvalho, L.P. ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters and Drug Resistance in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 151, 107315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Chen, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yu, Y. Nanotechnology Assisted Photo- and Sonodynamic Therapy for Overcoming Drug Resistance. Cancer Biol. Med. 2021, 18, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spring, B.Q.; Rizvi, I.; Xu, N.; Hasan, T. The Role of Photodynamic Therapy in Overcoming Cancer Drug Resistance. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2015, 14, 1476–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basmaciyan, L.; Casanova, M. Cell Death in Leishmania. Parasite 2019, 26, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basmaciyan, L.; Azas, N.; Casanova, M. A Potential Acetyltransferase Involved in Leishmania major Metacaspase-Dependent Cell Death. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compounds | Antipromastigote Activity (μM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC25 | IC50 | IC75 | ||||

| PDT− | PDT+ | PDT− | PDT+ | PDT− | PDT+ | |

| MB | 9.39 ± 2.03 | 2.73 ± 2.25 #,‡‡ | 61.44 ± 4.41 d | 29.33 ± 4.31 ## | 128.25 ± 0.07 | 106.55 ± 0.48 ## |

| NMB | 2.34 ± 0.07 | 2.50 ± 1.75 ‡‡ | 5.42 ± 0.81 d | 5.28 ± 2.19 ‡ | 35.21 ± 1.85 | 11.04 ± 0.04 ##,‡‡ |

| NMB-B | 3.73 ± 3.20 | 1.56 ± 0.81 ‡‡ | 5.48 ± 1.73 d | 3.48 ± 0.99 ‡ | 71.32 ± 3.56 | 10.70 ± 0.58 ##,‡‡ |

| NMB-P | 1.50 ± 0.28 | 0.73 ± 0.16 #,‡‡‡ | 2.84 ± 0.80 d | 2.48 ± 0.04 ‡ | 37.76 ± 8.91 | 7.20 ± 0.68 #,‡‡‡ |

| Miltefosine | 13.03 ± 1.82 | 23.30 ± 2.55 d | 42.43 ± 4.86 | |||

| Compounds | Conc. µM | Low Population | High Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFIH2DCFDA | VIROS | MFIH2DCFDA | VIROS | ||

| MB | 61.44 | 34,923.10 | 1.30 ± 0.59 | 1,084,378.70 * | 2.43 ± 0.63 |

| NMB | 5.42 | 20,513.35 | 0.78 ± 0.55 | 2,016,352.20 ** | 4.49 ± 0.53 |

| NMB-B | 5.48 | 78,465.10 | 2.73 ± 1.31 | 1,781,042.90 ** | 4.00 ± 1.00 |

| NMB-P | 2.84 | 69,333.50 | 2.39 ± 1.48 | 2,118,590.15 ** | 4.67 ± 0.13 |

| AA | 10.00 | 41,057.05 | 1.50 ± 0.31 | 897,705.20 | 1.99 ± 0.16 |

| LED-only | - | 21,828.05 | 0.82 ± 0.40 | 413,811.30 | 0.90 ± 0.22 |

| Control | - | 27,786.50 | - | 452,851.90 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vasco-dos-Santos, D.R.; Vacani-Martins, N.; Silva, F.C.M.d.; Alves, L.A.; Rocha, Z.N.d.; Henriques-Pons, A.; Torres-Santos, E.C.; Vannier-Santos, M.A. Light, Dyes, and Action: Photodynamic Inactivation of Leishmania amazonensis Using Methylene Blue, New Methylene Blue, and Novel Ruthenium-Based Derivatives. Biology 2025, 14, 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121710

Vasco-dos-Santos DR, Vacani-Martins N, Silva FCMd, Alves LA, Rocha ZNd, Henriques-Pons A, Torres-Santos EC, Vannier-Santos MA. Light, Dyes, and Action: Photodynamic Inactivation of Leishmania amazonensis Using Methylene Blue, New Methylene Blue, and Novel Ruthenium-Based Derivatives. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121710

Chicago/Turabian StyleVasco-dos-Santos, Deyvison Rhuan, Natália Vacani-Martins, Fabrício Cordeiro Moreira da Silva, Luiz Anastácio Alves, Zênis Novais da Rocha, Andrea Henriques-Pons, Eduardo Caio Torres-Santos, and Marcos André Vannier-Santos. 2025. "Light, Dyes, and Action: Photodynamic Inactivation of Leishmania amazonensis Using Methylene Blue, New Methylene Blue, and Novel Ruthenium-Based Derivatives" Biology 14, no. 12: 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121710

APA StyleVasco-dos-Santos, D. R., Vacani-Martins, N., Silva, F. C. M. d., Alves, L. A., Rocha, Z. N. d., Henriques-Pons, A., Torres-Santos, E. C., & Vannier-Santos, M. A. (2025). Light, Dyes, and Action: Photodynamic Inactivation of Leishmania amazonensis Using Methylene Blue, New Methylene Blue, and Novel Ruthenium-Based Derivatives. Biology, 14(12), 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121710