Differential Energy Metabolism in Skeletal Muscle Tissues of Yili Horses Based on Targeted Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

2.2. Muscle Section Preparation

2.3. Targeted Energy Metabolite Assay

2.3.1. Sample Preprocessing

2.3.2. Sample Detection

2.4. Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis

2.4.1. RNA Extraction and Library Construction

2.4.2. mRNA Data Processing and Analysis

2.4.3. miRNA Data Processing and Analysis

2.4.4. DEGs and DEmiR Enrichment Analysis

2.4.5. Construction of Metabolite-mRNA-miRNA Interaction Network

2.4.6. Real-Time Fluorescent Quantitative PCR

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

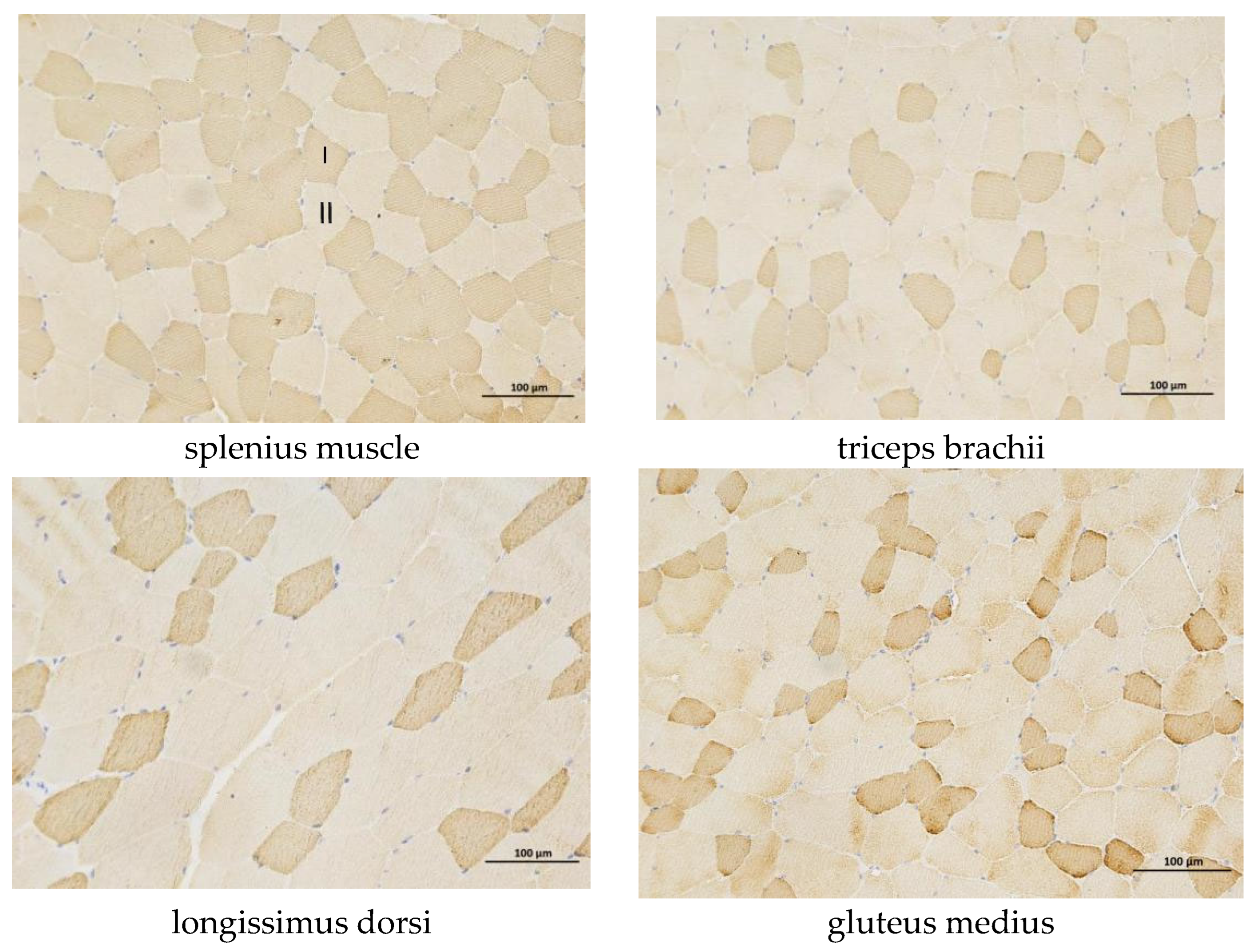

3.1. Differences in Skeletal Muscle Fibers Among Different Regions of the Yili Horse

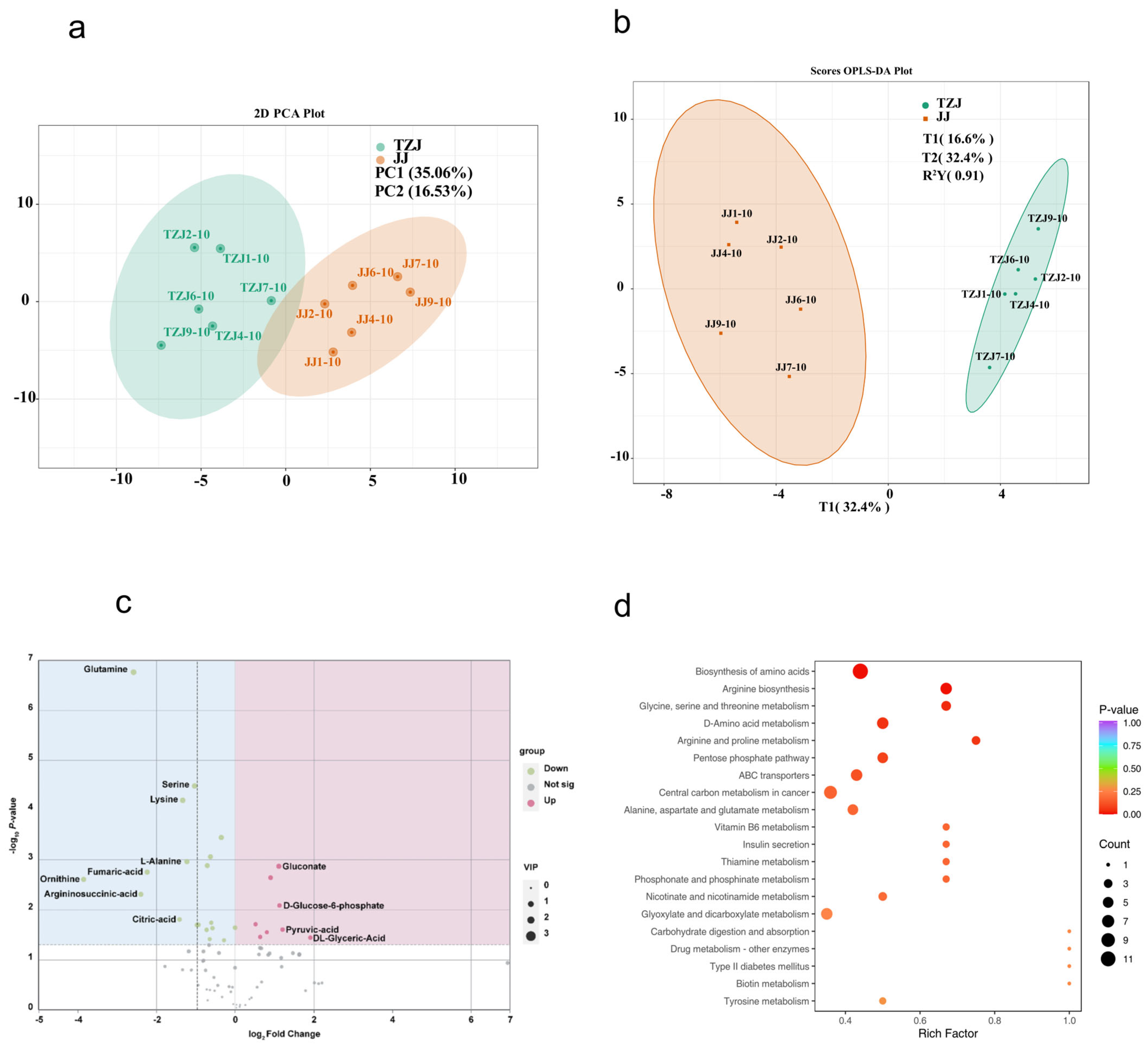

3.2. Targeted Energy Differential Metabolite Determination

3.2.1. Grouped Principal Component Analysis and OPLS-DA

3.2.2. Differential Metabolite Analysis

3.2.3. KEGG Analysis of Differential Metabolites

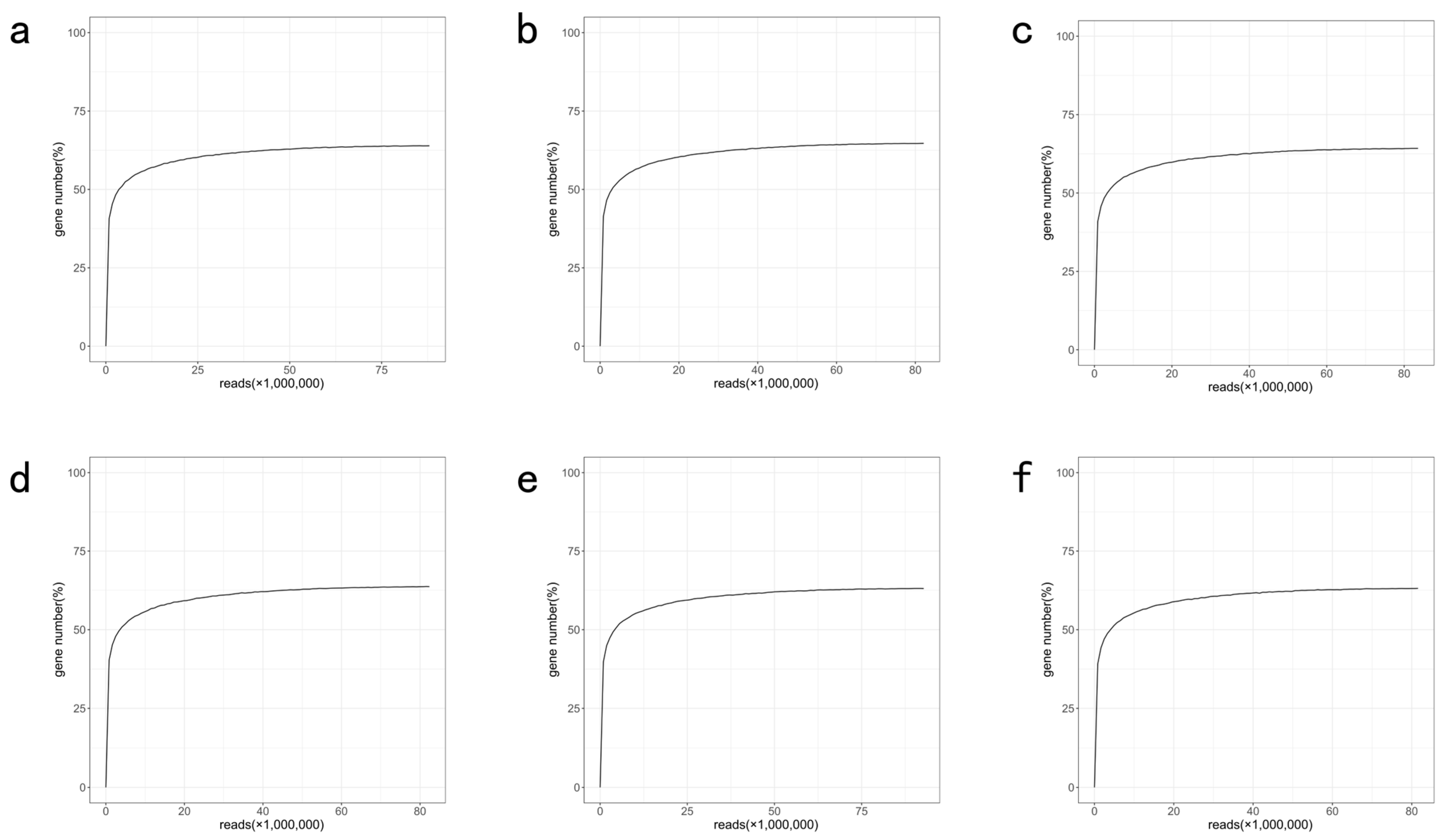

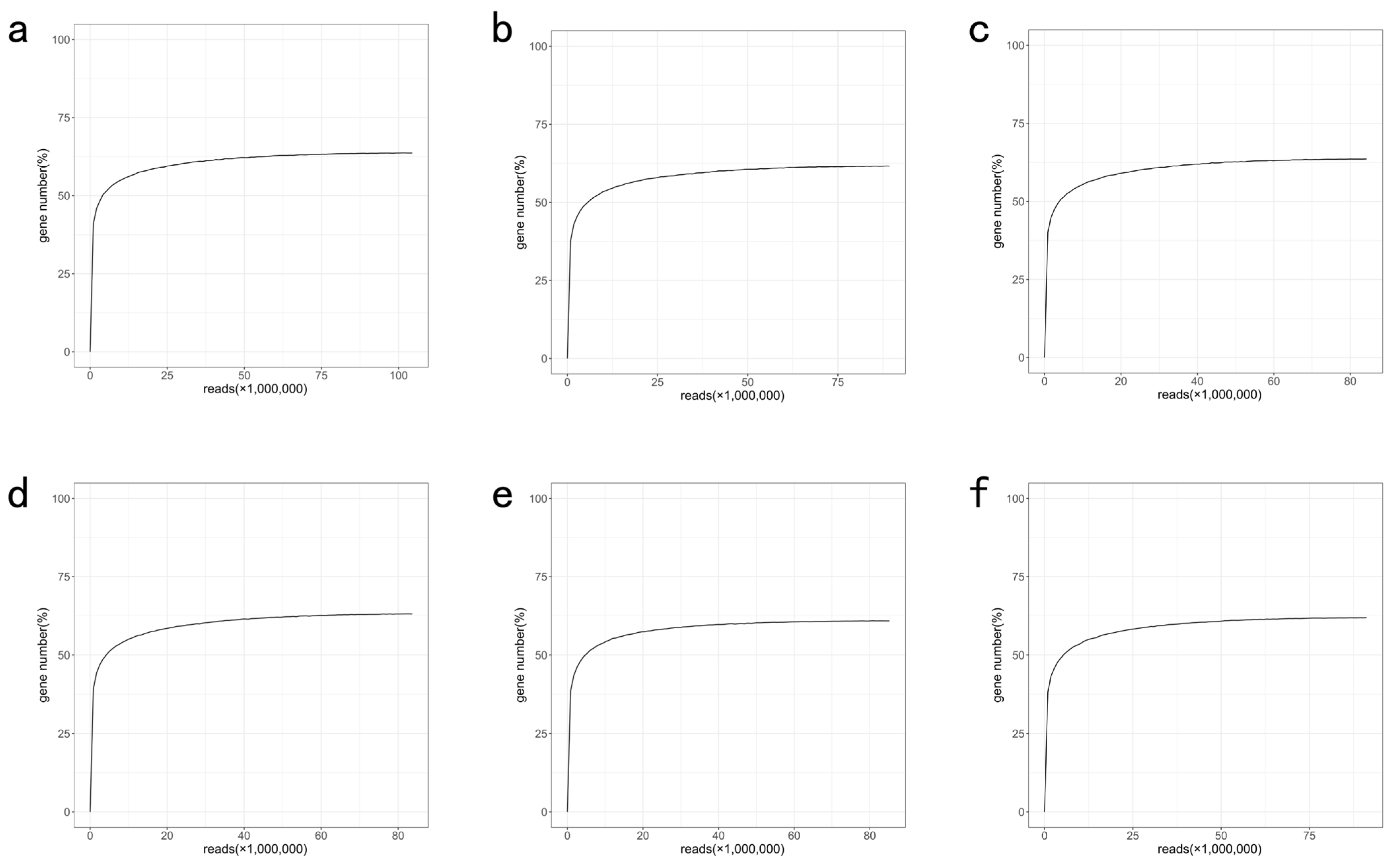

3.3. Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis Result

3.3.1. mRNA and miRNA Differential Expression Analysis

3.3.2. Enrichment Analysis of Target Genes for Differentially Expressed mRNAs and miRNAs

3.3.3. mRNA Protein–Protein Interactions (PPIs)

3.3.4. Correlation Analysis of DEGs and DMs

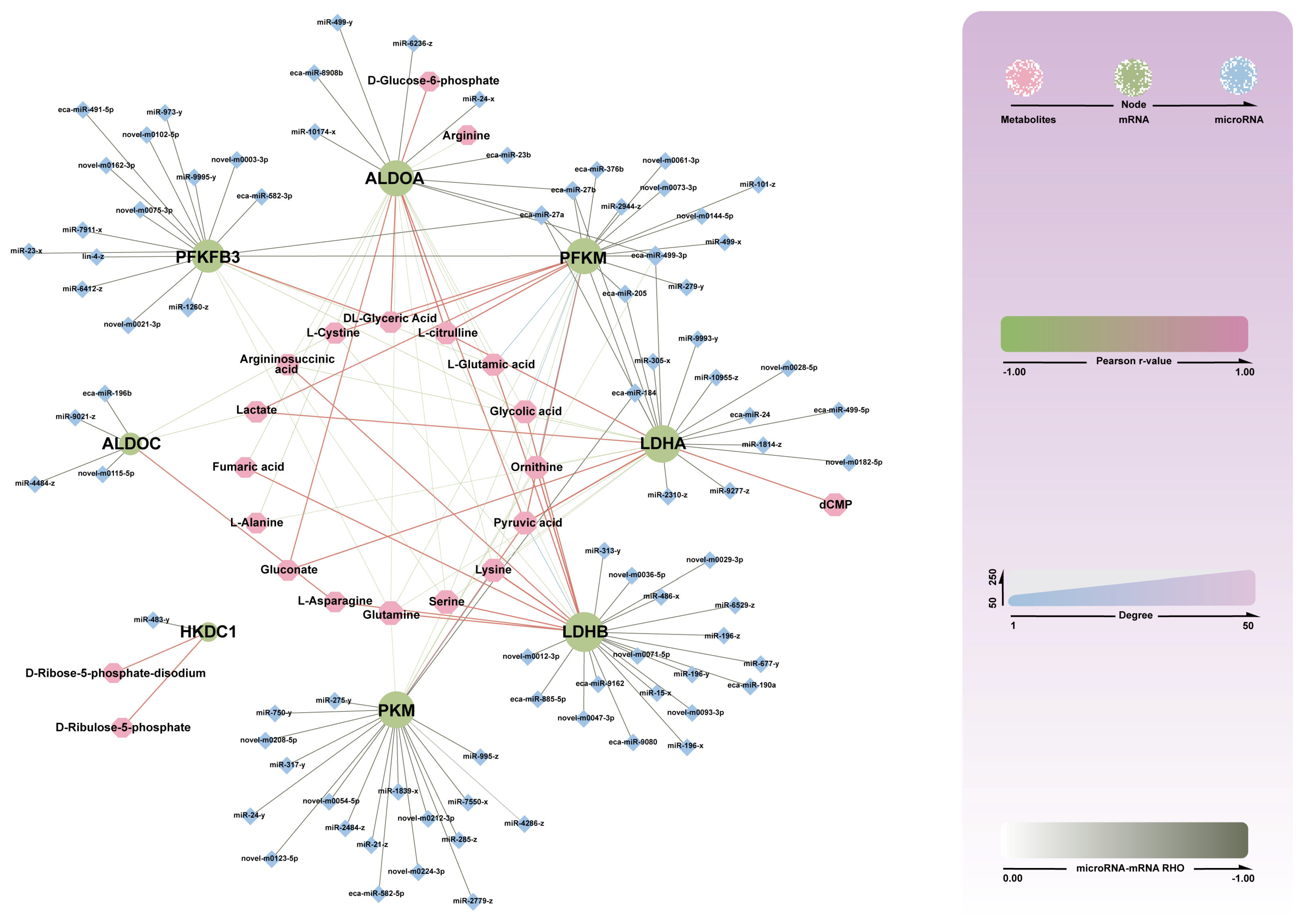

3.3.5. Construction of miRNA-mRMA-Metabolite Network

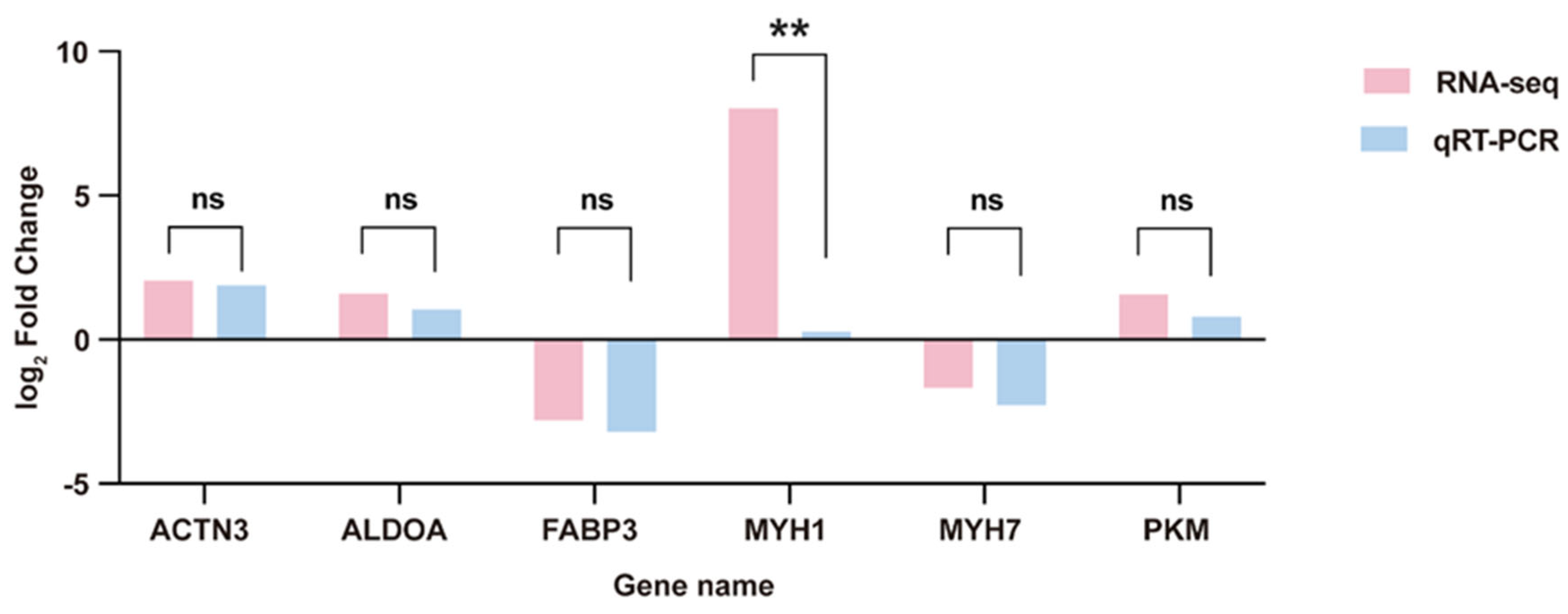

3.3.6. RT-qPCR Validation of mRNAs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sample | Raw Data (bp) | Clean Data (bp) | AF_Q20 (%) | AF_Q30 (%) | AF_GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JJ1 | 13,199,480,700 | 13,122,366,300 | 98.06% | 94.29% | 53.45% |

| JJ2 | 12,318,236,100 | 12,236,089,545 | 98.10% | 94.43% | 52.73% |

| JJ4 | 12,538,311,900 | 12,445,278,760 | 98.19% | 94.76% | 54.85% |

| JJ6 | 12.358,093,500 | 12,257,883,689 | 97.89% | 94.17% | 55.86% |

| JJ7 | 13,921,296,300 | 13,798,455,360 | 97.87% | 94.17% | 56.48% |

| JJ9 | 12,238,812,600 | 12,155,905,199 | 98.01% | 94.37% | 55.42% |

| TZJ1 | 15,664,848,300 | 15,575,239,447 | 98.25% | 94.81% | 54.46% |

| TZJ2 | 13,394,916,600 | 13,291,996,474 | 98.17% | 94.68% | 54.99% |

| TZJ4 | 12,642,682,500 | 12,548,268,292 | 98.21% | 94.86% | 55.24% |

| TZJ6 | 12,549,490,800 | 12,464,847,291 | 98.09% | 94.53% | 55.09% |

| TZJ7 | 12,779,957,400 | 12,729,639,875 | 98.16% | 94.71% | 55.35% |

| TZJ9 | 13,679,158,200 | 13,562,642,434 | 97.89% | 94.12% | 55.63% |

| Sample | Total | Unmapped (%) | Unique Mapped (%) | Multiple Mapped (%) | Total Mapped (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JJ1 | 85,220,450 | 24,171,841 (28.36%) | 53,329,465 (62.58%) | 7,719,144 (9.06%) | 61,048,609 (71.64%) |

| JJ2 | 79,839,962 | 16,434,587 (20.58%) | 56,619,830 (70.92%) | 6,785,545 (8.50%) | 63,405,375 (79.42%) |

| JJ4 | 80,365,626 | 22,305,613 (27.76%) | 47,878,326 (59.58%) | 10,181,687 (12.67%) | 58,060,013 (72.24%) |

| JJ6 | 79,024,234 | 20,471,147 (25.90%) | 47,937,663 (60.66%) | 10,615,424 (13.43%) | 58,553,087 (74.10%) |

| JJ7 | 88,507,630 | 23,218,567 (26.23%) | 53,935,327 (60.94%) | 11,353,736 (12.83%) | 65,289,063 (73.77%) |

| JJ9 | 78,170,250 | 27,655,376 (35.38%) | 39,918,915 (51.07%) | 10,595,959 (13.55%) | 50,514,874 (64.62%) |

| TZJ1 | 100,602,282 | 26,253,104 (26.10%) | 63,473,384 (63.09%) | 10,875,794 (10.81%) | 74,349,178 (73.90%) |

| TZJ2 | 85,659,920 | 24,533,391 (28.64%) | 51,520,889 (60.15%) | 9,605,640 (11.21%) | 61,126,529 (71.36%) |

| TZJ4 | 81,896,358 | 26,561,246 (32.43%) | 43,525,361 (53.15%) | 11,809,751 (14.42%) | 55,335,112 (67.57%) |

| TZJ6 | 81,062,762 | 21,788,362 (26.88%) | 4,692,202 (57.88%) | 12,352,371 (15.24%) | 59,274,400 (73.12%) |

| TZJ7 | 82,591,530 | 29,121,524 (35.26%) | 46,744,045 (56.60%) | 6,725,961 (8.14%) | 53,470,006 (64.74%) |

| TZJ9 | 86,962,266 | 30,874,280 (35.50%) | 43,799,729 (50.37%) | 12,288,257 (14.13%) | 56087,986 (64.50%) |

References

- Wang, J.; Ren, W.; Sun, Z.; Han, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Meng, J.; Yao, X. Comparative transcriptome analysis of slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscles in Kazakh horses. Meat Sci. 2024, 216, 109582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, T.; Sun, Z.; Meng, J.; Yao, X. Investigating age-related differences in muscles of Kazakh horse through transcriptome analysis. Gene 2024, 919, 148483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.X.; Zhai, Y.Y.; Ding, R.R.; Huang, J.H.; Shi, X.C.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.P.; Zhang, J.F.; Lu, J.F.; Zhang, Z.; et al. FNDC1 is a myokine that promotes myogenesis and muscle regeneration. EMBO J. 2025, 44, 30–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, E.; Guo, J.; Yin, J. Nutritional regulation of skeletal muscle energy metabolism, lipid accumulation and meat quality in pigs. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 14, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, B.; Shao, L.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Dai, R. Changes of mitochondrial lipid molecules, structure, cytochrome c and ROS of beef Longissimus lumborum and Psoas major during postmortem storage and their potential associations with beef quality. Meat Sci. 2023, 195, 109013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; Han, H.; Li, B.; Zhao, Y.; Bou, G.; Zhang, X.; Du, M.; Zhao, R.; Mongke, T.; Laxima; et al. The distinct transcriptomes of fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscles in Mongolian horses. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2020, 33, 100649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhou, X.; Chu, M.; Guo, X.; Pei, J.; Xiong, L.; Ma, X.; Bao, P.; Liang, C.; Yan, P. Whole transcriptome analyses and comparison reveal the metabolic differences between oxidative and glycolytic skeletal muscles of yak. Meat Sci. 2022, 194, 108948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Q.; Shi, X.; Yuan, W.; Liu, G.; Wang, C. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Slow-Twitch and Fast-Twitch Muscles in Dezhou Donkeys. Genes 2022, 13, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempere, L.F.; Freemantle, S.; Pitha-Rowe, I.; Moss, E.; Dmitrovsky, E.; Ambros, V. Expression profiling of mammalian microRNAs uncovers a subset of brain-expressed microRNAs with possible roles in murine and human neuronal differentiation. Genome Biol. 2004, 5, R13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.J. MicroRNA-206: The skeletal muscle-specific myomiR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1779, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.J. The MyomiR network in skeletal muscle plasticity. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2011, 39, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Chen, D.; Yu, B.; He, J.; Luo, J.; Luo, Y.; Chen, H.; Zheng, P.; et al. MicroRNA-499-5p regulates porcine myofiber specification by controlling Sox6 expression. Animal 2017, 11, 2268–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H. MicroRNA-152 Promotes Slow-Twitch Myofiber Formation via Targeting Uncoupling Protein-3 Gene. Animals 2019, 9, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yu, S.; Zhang, W.; Tang, Y.; Yin, L.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L.; et al. miR-196-5p regulates myogenesis and induces slow-switch fibers formation by targeting PBX1. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Bezprozvannaya, S.; Shelton, J.M.; Frisard, M.I.; Hulver, M.W.; McMillan, R.P.; Wu, Y.; Voelker, K.A.; Grange, R.W.; Richardson, J.A.; et al. Mice lacking microRNA 133a develop dynamin 2–dependent centronuclear myopathy. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 3258–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Lu, M.; Yao, X.; Xia, H.; Wang, Y.-C.; Liu, M.-F.; Jiang, J.; et al. Thyroid hormone regulates muscle fiber type conversion via miR-133a1. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 207, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Yang, J.; Jiang, R.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Huang, Y.; Lan, X.; Lei, C.; Ma, Y.; Qi, X.; et al. miR-148a-3p regulates proliferation and apoptosis of bovine muscle cells by targeting KLF6. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 15742–15750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, E.E.; Zhang, X.; Hoffmann, C.; Hughes, L.D.; Lewis, S.A.; Li, J.; Wallace, M.J.; Riley, L.; Douglas, C.M.; Gutierrez-Montreal, M.A.; et al. Transcriptional profiling reveals extraordinary diversity among skeletal muscle tissues. eLife 2018, 7, e34613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zha, C.; Jiang, A.; Chao, Z.; Hou, L.; Liu, H.; Huang, R.; Wu, W. A Combined Differential Proteome and Transcriptome Profiling of Fast- and Slow-Twitch Skeletal Muscle in Pigs. Foods 2022, 11, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Yang, H.; Bai, Y.; Li, Q.; Qi, X.; Li, D.; Zhao, X.; Ma, Y. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics reveal the molecular characteristics and metabolic regulatory mechanisms among different muscles in Minxian black fur sheep. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, B.; Zierath, J.R. Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 162–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, M.A.; Birnbaum, M.J. Molecular aspects of fructose metabolism and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 2329–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Li, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Xie, B.; Groenen, M.A.M.; Madsen, O.; Yang, X.; Tang, Z. Integrative metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals difference in glucose and lipid metabolism in the longissimus muscle of Luchuan and Duroc pigs. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1128033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, J.Y.; Mansfield, B.C. Mutations in the glucose-6-phosphatase-alpha (G6PC) gene that cause type Ia glycogen storage disease. Hum. Mutat. 2008, 29, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukita, A.; Yoshida, M.C.; Fukushige, S.; Sakakibara, M.; Joh, K.; Mukai, T.; Hori, K. Molecular gene mapping of human aldolase A (ALDOA) gene to chromosome 16. Hum. Genet. 1987, 76, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenting, W.; Hongxiang, L.; Jiamei, X.; Fan, Y.; Lijia, X.; Baoping, J.; Peigen, X. Aqueous Extract of Black Maca Prevents Metabolism Disorder via Regulating the Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis-TCA Cycle and PPARα Signaling Activation in Golden Hamsters Fed a High-Fat, High-Fructose Diet. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, J.-A.; Ayarpadikannan, S.; Eo, J.; Kwon, Y.-J.; Choi, Y.; Lee, H.-K.; Park, K.-D.; Yang, Y.M.; Cho, B.-W.; Kim, H.-S. Transcriptional expression changes of glucose metabolism genes after exercise in thoroughbred horses. Gene 2014, 547, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Sun, A.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, D.; Xie, Y.; Hou, X.; Zheng, F.; et al. Increased glycolysis in skeletal muscle coordinates with adipose tissue in systemic metabolic homeostasis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 7840–7854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsin, A.-S.; Bouzin, C.; Bertrand, L.; Hue, L. The stimulation of glycolysis by hypoxia in activated monocytes is mediated by AMP-activated protein kinase and inducible 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 30778–30783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.-H.; Flechner, L.; Qi, L.; Zhang, X.; Screaton, R.A.; Jeffries, S.; Hedrick, S.; Xu, W.; Boussouar, F.; Brindle, P.; et al. The CREB coactivator TORC2 is a key regulator of fasting glucose metabolism. Nature 2005, 437, 1109–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerblad, H.; Bruton, J.D.; Katz, A. Skeletal muscle: Energy metabolism, fiber types, fatigue and adaptability. Exp. Cell Res. 2010, 316, 3093–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Yao, Y.L.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Tang, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, K.; Tang, Z. Comprehensive Profiles of mRNAs and miRNAs Reveal Molecular Characteristics of Multiple Organ Physiologies and Development in Pigs. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Li, Z.; Jin, L.; Long, K.; Lu, L.; Ge, L. miR-205 Regulates the Fusion of Porcine Myoblast by Targeting the Myomaker Gene. Cells 2023, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, M.A.; Powell, R.; Bruce, T.; Bridges, W.C.; Duckett, S.K. miRNA transcriptome and myofiber characteristics of lamb skeletal muscle during hypertrophic growth 1. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 988756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Luo, W.; Chen, G.; Chen, J.; Lin, S.; Ren, T.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, C.; Wen, H.; Nie, Q.; et al. Chicken muscle antibody array reveals the regulations of LDHA on myoblast differentiation through energy metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, G.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, G.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, P.; Fan, M.; et al. Transforming growth factor-beta-regulated miR-24 promotes skeletal muscle differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 2690–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, D.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yan, C.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Yu, M.; Xie, B.; Tang, Z. Regulation of myo-miR-24-3p on the Myogenesis and Fiber Type Transformation of Skeletal Muscle. Genes 2024, 15, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; He, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, T.; Xie, K.; Dai, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G. miRNA-seq analysis in skeletal muscle of chicken and function exploration of miR-24-3p. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, E.; Quiat, D.; Johnson, B.A.; Sutherland, L.B.; Qi, X.; Richardson, J.A.; Kelm, R.J., Jr.; Olson, E.N. A family of microRNAs encoded by myosin genes governs myosin expression and muscle performance. Dev. Cell 2009, 17, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Rumsey, J.; Hazen, B.C.; Lai, L.; Leone, T.C.; Vega, R.B.; Xie, H.; Conley, K.E.; Auwerx, J.; Smith, S.R.; et al. Nuclear receptor/microRNA circuitry links muscle fiber type to energy metabolism. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 2564–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Chen, D.; Yang, T.; Liu, G. Role of microRNA-27a in myoblast differentiation. Cell Biol. Int. 2014, 38, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, C.G.; Montarras, D.; Pallafacchina, G.; Rocancourt, D.; Cumano, A.; Conway, S.J.; Buckingham, M. Muscle stem cell behavior is modified by microRNA-27 regulation of Pax3 expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13383–13387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, X.; Yu, B.; He, J.; Chen, D. MicroRNA-27a promotes myoblast proliferation by targeting myostatin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 423, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou, T.; Han, H.; Mongke, T.; Zhao, R.; La, X.; Ding, W.; Jia, Z.; Liu, H.; Tiemuqier, A.; An, T.; et al. Fast and slow myofiber-specific expression profiles are affected by noncoding RNAs in Mongolian horses. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2021, 41, 100942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene ID | Gene | Primer Name | Primer Sequence | Product Size (bp) | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100033871 | ACTN3 | ACTN3-F | GGTGAACCAGGAAAACGA | 160 | NM_001163869.1 |

| ACTN3-R | CCGGTAGTCCCGAAAGTC | 160 | |||

| 100033895 | FABP3 | FABP3-F | AGCACCTTCAAGAACACGG | 114 | NM_001163885.3 |

| FABP3-R | GACAAGTTTGCCTCCATCC | 114 | |||

| 100063687 | PKM | PKM-F | GTTTGCGTCTTTCATCCG | 120 | NM_001143794.2 |

| PKM-R | AACCTCCGAACTCCCTCA | 120 | |||

| 100066121 | ALDOA | ALDOA-F | AACCGACGCTTCTACCGC | 144 | XM_005598801.4 |

| ALDOA-R | GCCCTTGGATTTGATAACTT | 144 | |||

| 791234 | MYH7 | MYH7-F | AACGCCTTTGATGTGCTG | 110 | NM_001081758.1 |

| MYH7-R | TCTCGCTGCTTCTGCTTG | 110 | |||

| 791235 | MYH1 | MYH1-F | CTGGTCTCCTGGGGCTCCTA | 72 | NM_001081759.1 |

| MYH1-R | TGGCCTGGGTTCGGGTAA | 72 | |||

| 100060464 | EEF1A2 | 18S-F | AGAAACGGCTACCACATCC | 169 | XM_023626927.2 |

| 18S-R | CACCAGACTTGCCCTCCA | 169 |

| Reagent Name | Volume (μL) | Step | Time (Sec) | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2xqPCRmix | 5.0 | 95 °C | 30 | |

| F primer (10 pmol/μL) | 0.25 | 95 °C | 10 | 40 cycles |

| R primer (10 pmol/μL) | 0.25 | 60 °C | 30 | |

| DNA template | 2.0 | 95 °C | 15 | |

| ddH2O | 2.5 | 60 °C | 60 | Detect once every 0.5 °C increase in temperature |

| total | 10.0 | 95 °C | 15 |

| Part | Average Slow Muscle Area | Proportion of Slow Muscle Fiber Area |

|---|---|---|

| longissimus dorsi | 1894.45 ± 385.76 Bb | 17.08 ± 3.98 Aa |

| triceps brachii | 1576.91 ± 673.28 ABab | 16.36 ± 7.35 Aa |

| splenius muscle | 2583.59 ± 449.98 Cc | 37.57 ± 4.69 Bb |

| gluteus medius | 1295.75 ± 284.77 Aa | 14.64 ± 5.49 Aa |

| Compounds | VIP | p-Value | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamine | 1.71 | 0.00 | down |

| L-Asparagine | 1.17 | 0.02 | down |

| L-Alanine | 1.42 | 0.00 | down |

| L-citrulline | 1.48 | 0.00 | up |

| Ornithine | 1.51 | 0.00 | down |

| Arginine | 1.48 | 0.00 | down |

| L-Cystine | 1.17 | 0.04 | up |

| Lysine | 1.62 | 0.00 | down |

| Serine | 1.60 | 0.00 | down |

| L-Glutamate | 1.54 | 0.00 | down |

| Threonine | 1.19 | 0.02 | down |

| D-Glycerate | 1.22 | 0.04 | up |

| Gluconate | 1.36 | 0.00 | up |

| Glycolate | 1.47 | 0.00 | down |

| dCMP | 1.31 | 0.02 | up |

| Fumarate | 1.52 | 0.00 | down |

| L-Malic acid | 1.08 | 0.04 | down |

| L-Argininosuccinate | 1.46 | 0.00 | down |

| Pyruvic acid | 1.26 | 0.03 | up |

| Lactate | 1.16 | 0.02 | up |

| Alpha-Ketoglutaric Acid | 1.08 | 0.04 | down |

| Citric acid | 1.31 | 0.02 | down |

| Xylulose-5-phosphate | 1.22 | 0.03 | down |

| D-Ribose 5-phosphate | 1.28 | 0.02 | down |

| D-Ribulose 5-phosphate | 1.28 | 0.02 | down |

| D-Mannose 6-phosphate | 1.07 | 0.03 | up |

| D-Glucose 6-phosphate | 1.26 | 0.01 | up |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Meng, C.; Xue, Y.; Shen, Z.; Ren, W.; Zeng, Y.; Meng, J. Differential Energy Metabolism in Skeletal Muscle Tissues of Yili Horses Based on Targeted Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analysis. Biology 2025, 14, 1713. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121713

Li X, Meng C, Xue Y, Shen Z, Ren W, Zeng Y, Meng J. Differential Energy Metabolism in Skeletal Muscle Tissues of Yili Horses Based on Targeted Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analysis. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1713. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121713

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xueyan, Chen Meng, Yuheng Xue, Zhehong Shen, Wanlu Ren, Yaqi Zeng, and Jun Meng. 2025. "Differential Energy Metabolism in Skeletal Muscle Tissues of Yili Horses Based on Targeted Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analysis" Biology 14, no. 12: 1713. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121713

APA StyleLi, X., Meng, C., Xue, Y., Shen, Z., Ren, W., Zeng, Y., & Meng, J. (2025). Differential Energy Metabolism in Skeletal Muscle Tissues of Yili Horses Based on Targeted Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analysis. Biology, 14(12), 1713. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121713