From Dyes to Drugs? Selective Leishmanicidal Efficacy of Repositioned Methylene Blue and Its Derivatives in In Vitro Evaluation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

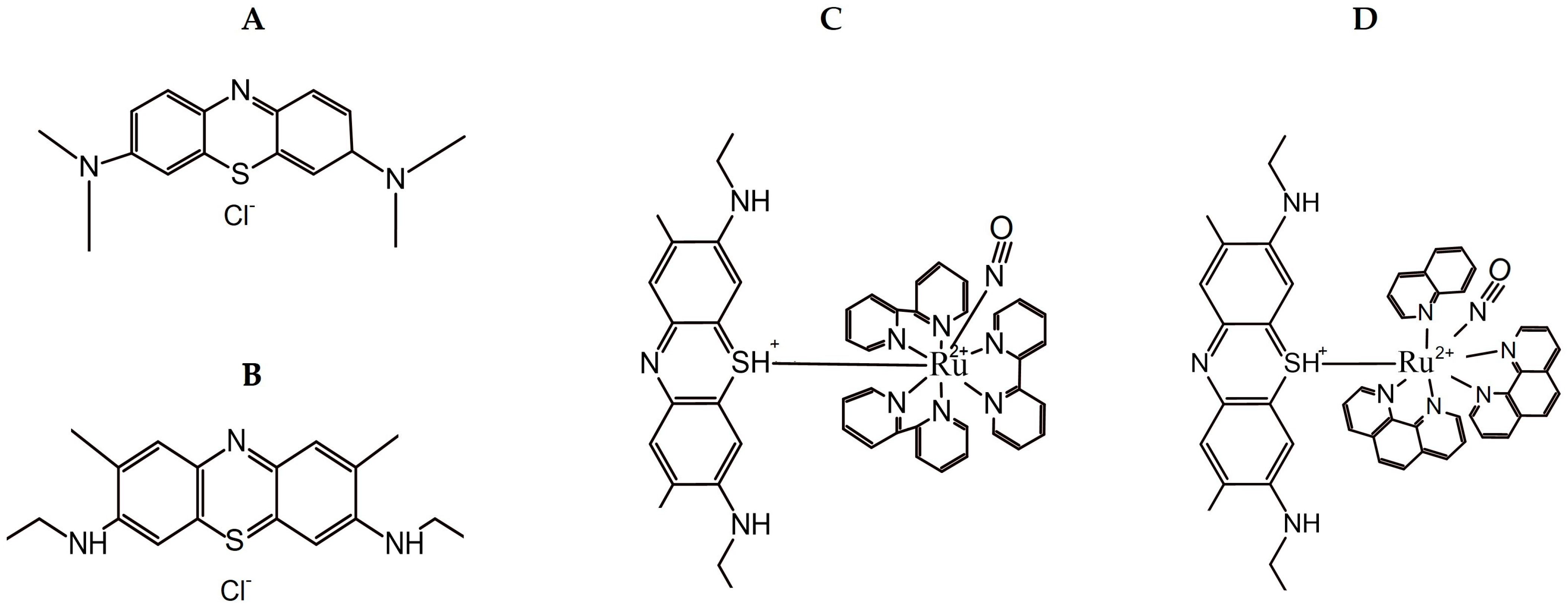

2.1. Compounds and Reagents

2.2. Synthesis of Ruthenium Complexes

2.3. Ethical and Animal Statements

2.4. Culture of Parasitic Cells

2.5. Culture of Mammalian Host Cells

2.6. Leishmanicidal Activity Assay: Evaluation of Promastigotes and Ex Vivo Amastigotes

2.7. Cytotoxicity Assays on Different Mammalian Cell Types and Selective Indexes

2.8. Evaluation of Mechanisms of Action by Flow Cytometry

2.8.1. Determination of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential—ΔΨm

2.8.2. Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species—ROS

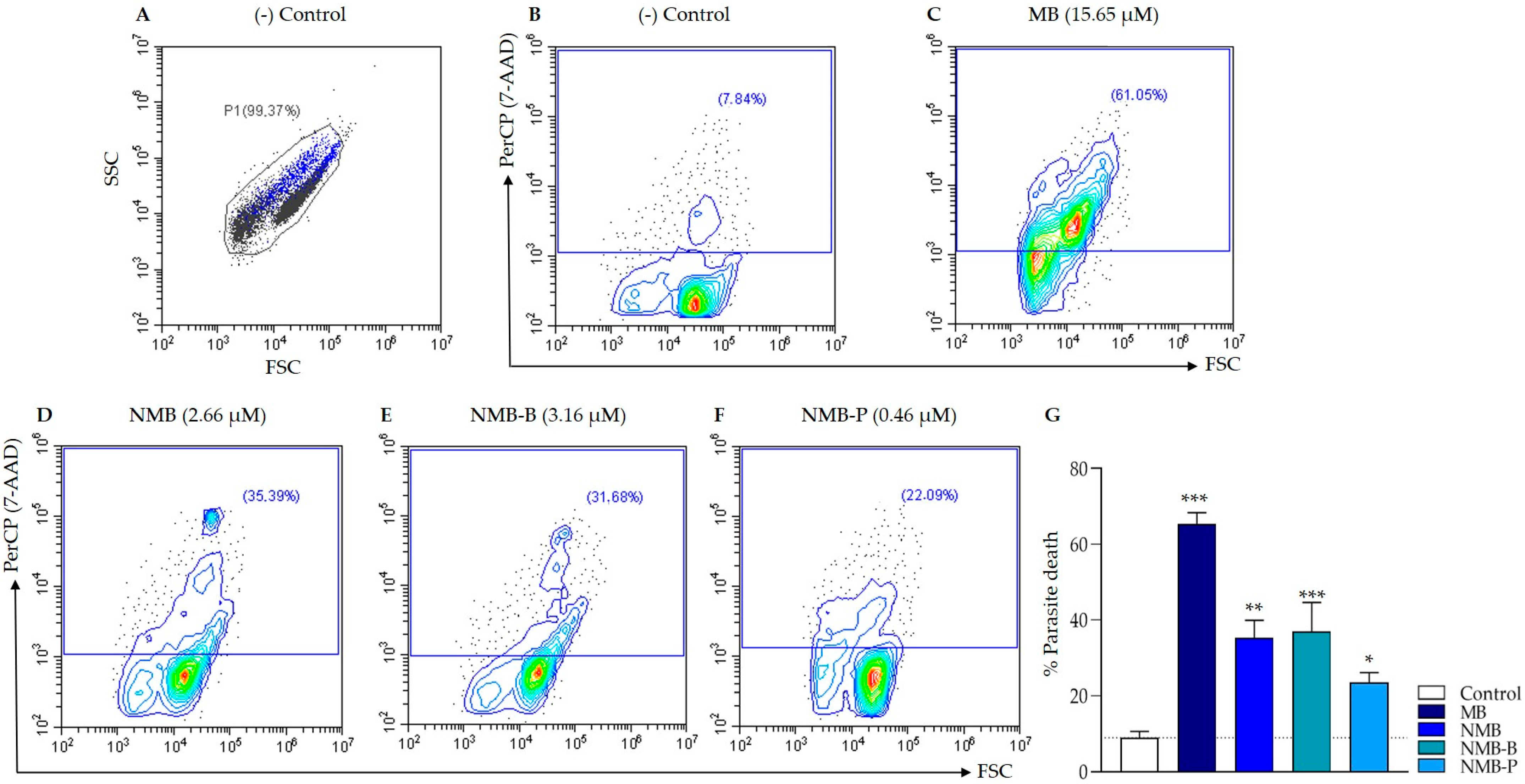

2.8.3. Cell Death: Phosphatidylserine Exposure and Plasma Membrane Integrity

2.8.4. Image Flow Cytometry

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

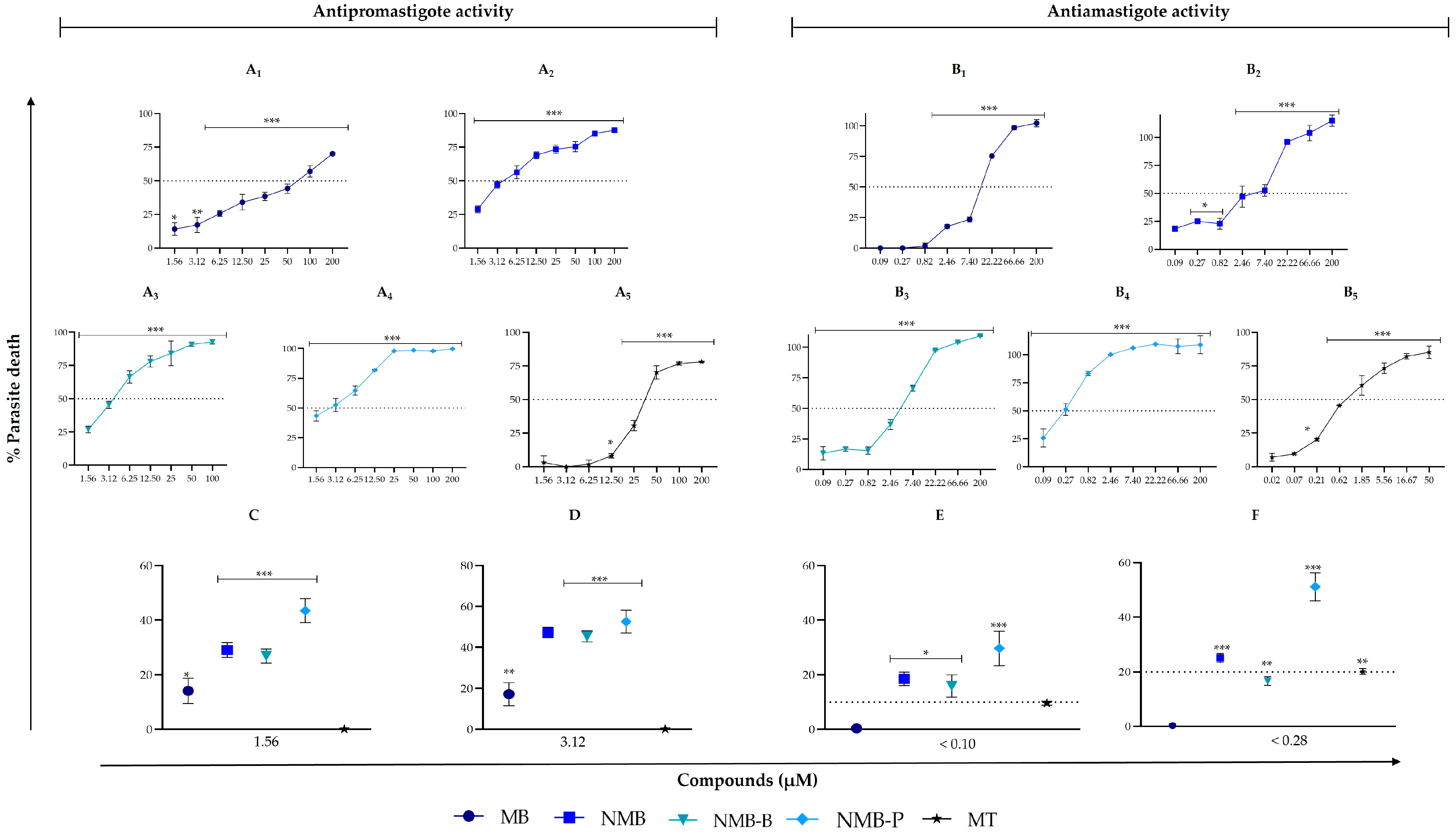

3.1. Compounds Surpass the Efficacy of the Reference Drug in Inhibiting Different Forms of Leishmania amazonensis

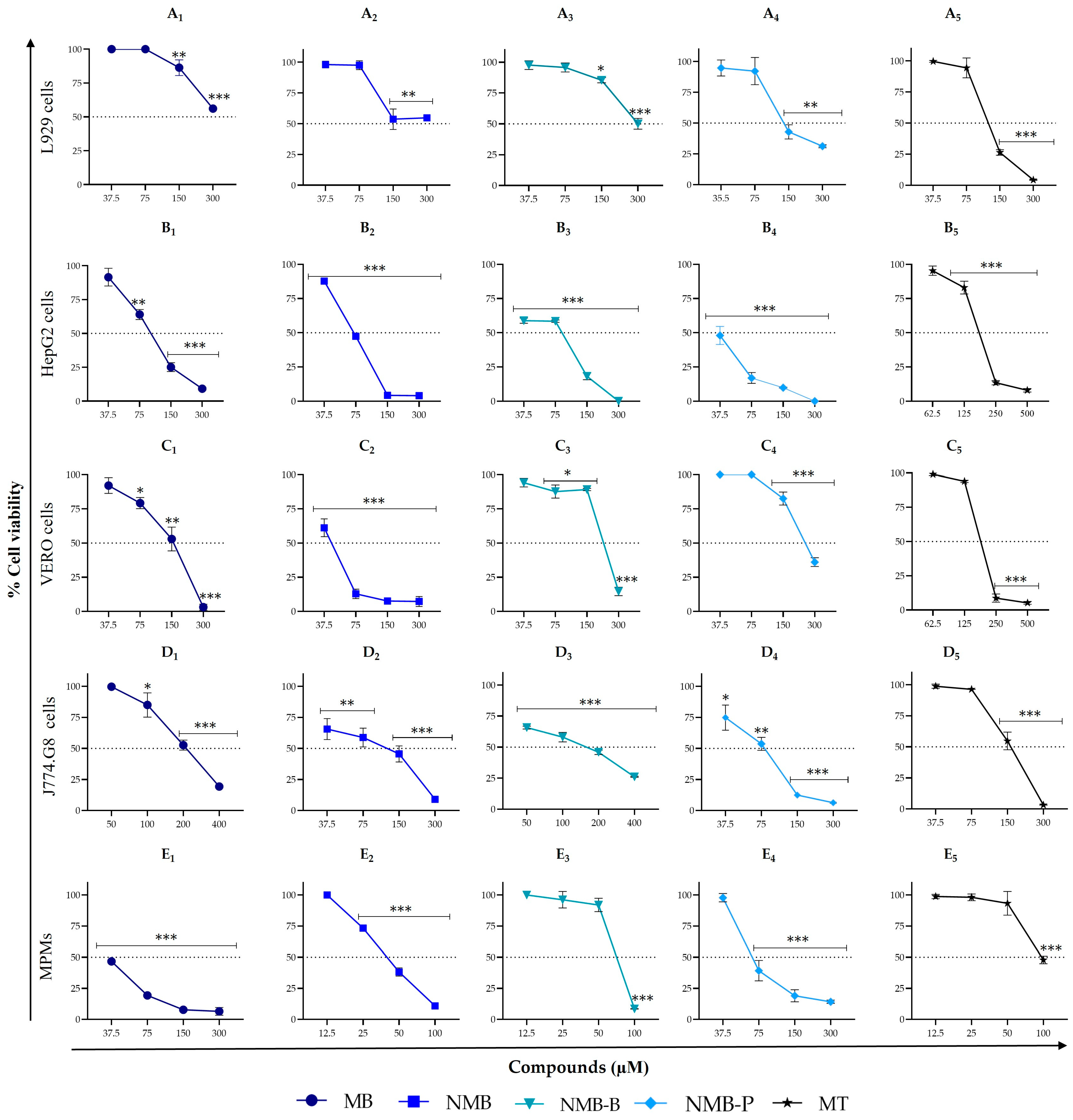

3.2. Cytotoxicity on Different Mammalian Cell Types: Selective Efficacy of Repositioned and Novel Compounds

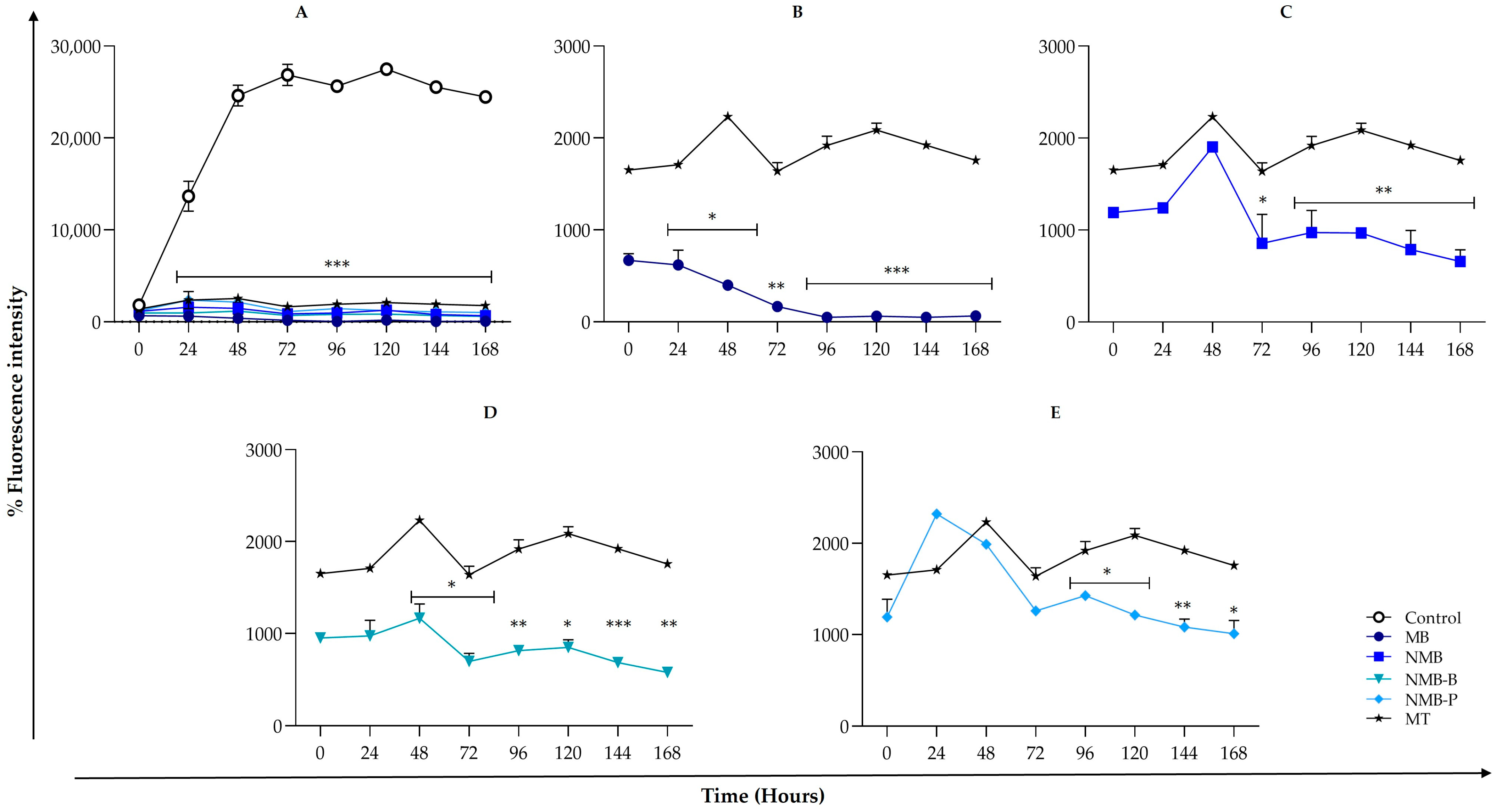

3.3. Leishmania amazonensis ΔΨm Reduction

3.4. ROS Production Triggering

3.5. Cellular Death in Leishmania amazonensis: Potential Mechanisms from Early Apoptosis to Necrosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, Y.S.; Sun, Z.S.; Zheng, J.X.; Zhang, S.X.; Yin, J.X.; Zhao, H.Q.; Shen, H.M.; Baneth, G.; Chen, J.H.; Kassegne, K. Prevalence and Attributable Health Burdens of Vector-Borne Parasitic Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 1990–2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2024, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero, N.N.H.; Uriarte, M. Environmental and Socioeconomic Risk Factors Associated with Visceral and Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Systematic Review. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, S.; Saudagar, P. Leishmaniasis: Where are We and Where are We Heading? Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis Overview. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/leishmaniasis#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Silva, A.P.O.; Miranda, D.E.O.; Santos, M.A.B.; Guerra, N.R.; Marques, S.R.; Alves, L.C.; Ramos, R.A.N.; Carvalho, G.A. Phlebotomines in an Area Endemic for American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Northeastern Coast of Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2017, 26, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Serafim, T.D.; Coutinho-Abreu, I.V.; Dey, R.; Kissinger, R.; Valenzuela, J.G.; Oliveira, F.; Kamhawi, S. Leishmaniasis: The Act of Transmission. Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimann, M.M.; Torres-Santos, E.C.; Souza, C.S.F.; Andrade-Neto, V.V.; Jansen, A.M.; Brazil, R.P.; Roque, A.L.R. Oral and Intragastric: New Routes of Infection by Leishmania braziliensis and Leishmania infantum? Pathogens 2022, 11, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daga, R.; Mishra, R.; Rohatgi, I. Leishmaniasis. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, S166–S170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Barral, A.; Costa, J.M.L.; Bittencourt, A.L.; Barral-Netto, M.; Carvalho, E.M. Polar and Subpolar Diffuse Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Brazil: Clinical and Immunopathologic Aspects. Int. J. Dermatol. 1995, 34, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OPAS, Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Manual de Procedimientos para Vigilancia y Control de las Leishmaniasis en las Américas; Organización Panamericana de la Salud: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; ISBN 9789275320631. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, V.; Barros, N.B.; Macedo, S.R.A.; Ferreira, A.S.; Kanis, L.A.; Nicolete, R. Drug-Containing Hydrophobic Dressings as a Topical Experimental Therapy for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. J. Parasit. Dis. 2020, 44, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, I.; De Brouwere, V.; Belrhiti, Z.; Sahibi, H.; Boelaert, M. Psychosocial Burden of Localised Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, L.J.; Van Wijk, R.; Van Selm, L.; Rivera, A.; Barbosa, M.C.; Parisi, S.; Van Brakel, W.H.; Arevalo, J.; Quintero, W.; Waltz, M.; et al. Stigma, Participation Restriction and Mental Distress in Patients Affected by Leprosy, Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and Chagas Disease: A Pilot Study in Two Co-Endemic Regions of Eastern Colombia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 114, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpedo, G.; Pacheco-Fernandez, T.; Holcomb, E.A.; Cipriano, N.; Cox, B.; Satoskar, A.R. Mechanisms of Immunopathogenesis in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and Post Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis (PKDL). Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 685296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, S.; Madhukar, P.; Kumar, R. Anti-Leishmanial Therapies: Overcoming Current Challenges with Emerging Therapies. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2024, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Guerrero, E.; Quintanilla-Cedillo, M.R.; Ruiz-Esmenjaud, J.; Arenas, R. Leishmaniasis: A Review. F1000Research 2017, 6, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, D.S.S.; Miranda, B.M.; Fialho Martins, T.V.; Guimarães Ervilha, L.O.; Souza, A.C.F.; Emerick, S.O.; Silva, A.C.; Novaes, R.D.; Neves, M.M.; Santos, E.C.; et al. Lipophosphoglycan-3 Recombinant Protein Vaccine Controls Hepatic Parasitism and Prevents Tissue Damage in Mice Infected by Leishmania infantum chagasi. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 126, 110097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periferakis, A.; Caruntu, A.; Periferakis, A.-T.; Scheau, A.-E.; Badarau, I.A.; Caruntu, C.; Scheau, C. Availability, Toxicology and Medical Significance of Antimony. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, L.F.; Schubach, A.O.; Martins, M.M.; Passos, S.L.; Oliveira, R.V.; Marzochi, M.C.; Andrade, C.A. Systematic Review of the Adverse Effects of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Treatment in the New World. Acta Trop. 2011, 118, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.; Chakravarty, J. Antimony Toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 4267–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, S.; Chappuis, F.; Singh, R.; Boelaert, M.; Loutan, L.; Koirala, S. Sodium Stibogluconate Cardiotoxicity and Safety of Generics. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 97, 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, J.M.; García-Martínez, C.E.; Saldarriaga, C.; Pérez, G.E.; Melo, M.B.; Wyss, F.; Sosa-Liprandi, Á.; Ortiz-Lopez, H.I.; Gupta, S.; López-Santi, R.; et al. Leishmaniasis y Corazón. Arch. Cardiol. Méx. 2022, 92, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.C.; Morais-Teixeira, E.; Reis, P.G.; Silva-Barcellos, N.M.; Salaün, P.; Campos, P.P.; Corrêa-Junior, J.D.; Rabello, A.; Demicheli, C.; Frézard, F. Hepatotoxicity of Pentavalent Antimonial Drug: Possible Role of Residual Sb(III) and Protective Effect of Ascorbic Acid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.I.S.; Arruda, V.O.; Alves, E.V.C.; Azevedo, A.P.S.; Monteiro, S.G.; Pereira, S.R.F. Genotoxic Effects of the Antileishmanial Drug Glucantime®. Arch. Toxicol. 2010, 84, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, E.A.G.; Ahmed, A.E.; Musa, A.E.; Hussein, M.M. Antimony-Induced Cerebellar Ataxia. Saudi Med. J. 2006, 27, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maristany Bosch, M.; Cuervo, G.; Martín, E.M.; Heras, M.V.; Pérez, J.P.; Yélamos, S.M.; Fernández, N.S. Neurological Toxicity Due to Antimonial Treatment for Refractory Visceral Leishmaniasis. Clin. Neurophysiol. Pract. 2021, 6, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.L.O.; Costa, R.S.; Souza, C.S.; Foss, N.T.; Roselino, A.M.F. Nephrotoxicity Attributed to Meglumine Antimoniate (Glucantime) in the Treatment of Generalized Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. 1999, 41, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Luo, C.; Zheng, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Ding, W.; Shen, Z.; Xue, P.; Yu, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. TRPML1 Contributes to Antimony-Induced Nephrotoxicity by Initiating Ferroptosis via Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 184, 114378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, D.J.; Guimaraes, L.H.; Machado, P.R.L.; D’Oliveira, A.; Almeida, R.P.; Lago, E.L.; Faria, D.R.; Tafuri, W.L.; Dutra, W.O.; Carvalho, E.M. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis During Pregnancy: Exuberant Lesions and Potential Fetal Complications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S.A.; Merlotto, M.R.; Ramos, P.M.; Marques, M.E.A. American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis: Severe Side Effects of Pentavalent Antimonial in a Patient with Chronic Renal Failure. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2019, 94, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, N.C.; Rabello, A.; Cota, G.F. Efficacy of Pentavalent Antimoniate Intralesional Infiltration Therapy for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, M.; Ben-Shimol, S. Review of Leishmaniasis Treatment: Can We See the Forest through the Trees? Pharmacy 2024, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roatt, B.M.; Cardoso, J.M.O.; Brito, R.C.F.; Coura-Vital, W.; Aguiar-Soares, R.D.O.; Reis, A.B. Recent Advances and New Strategies on Leishmaniasis Treatment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8965–8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte-Sucre, A.; Gamarro, F.; Dujardin, J.C.; Barrett, M.P.; López-Vélez, R.; García-Hernández, R.; Pountain, A.W.; Mwenechanya, R.; Papadopoulou, B. Drug Resistance and Treatment Failure in Leishmaniasis: A 21st Century Challenge. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0006052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Tovar, T.F.; Sacriste-Hernández, M.I.; Juárez-Durán, E.R.; Arenas, R. An Overview of the Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Fac. Rev. 2020, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNDi, Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative. Leishmaniose Cutânea. Available online: https://dndial.org/doencas/leishmaniose-cutanea#dados/ (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Ayyar, P.; Subramanian, U. Repurposing—Second Life for Drugs. Pharmacia 2022, 69, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakate, R.; Kimura, T. Drug Repositioning Trends in Rare and Intractable Diseases. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchholz, K.; Schirmer, R.H.; Eubel, J.K.; Akoachere, M.B.; Dandekar, T.; Becker, K.; Gromer, S. Interactions of Methylene Blue with Human Disulfide Reductases and Their Orthologues from Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleby, B.; Cummings, J. Discovering New Treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease by Repurposing Approved Medications. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 2306–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeschke, H.; Akakpo, J.Y.; Umbaugh, D.S.; Ramachandran, A. Novel Therapeutic Approaches Against Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury and Acute Liver Failure. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 174, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabholkar, N.; Gorantla, S.; Dubey, S.K.; Alexander, A.; Taliyan, R.; Singhvi, G. Repurposing Methylene Blue in the Management of COVID-19: Mechanistic Aspects and Clinical Investigations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 112023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheshwari, A.; Seth, A.; Kaur, S.; Aneja, S.; Rath, B.; Basu, S.; Patel, R.; Dutta, A.K. Cumulative Cardiac Toxicity of Sodium Stibogluconate and Amphotericin B in Treatment of Kala-Azar. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011, 30, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiklund, L.; Basu, S.; Miclescu, A.; Wiklund, P.; Ronquist, G.; Sharma, H.S. Neuro- and Cardioprotective Effects of Blockade of Nitric Oxide Action by Administration of Methylene Blue. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1122, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanos-Cuentas, A.; Valencia, B.M.; Petersen, C.A. Neurological Manifestations of Human Leishmaniasis. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 114, pp. 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, C.S.F.; Monteiro, M.C.; Gavioli, E.C.; Oliveira, F.R.; Oliveira, G.B.; Romão, P.R.T. Neurological Disease in Human and Canine Leishmaniasis—Clinical Features and Immunopathogenesis. Parasite Immunol. 2015, 37, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannuzzi, A.P.; Ricciardi, M.; De Simone, A.; Gernone, F. Neurological Manifestations in Dogs Naturally Infected by Leishmania infantum: Descriptions of 10 Cases and a Review of the Literature. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2017, 58, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, C.A.; Greenlee, M.H.W. Neurologic Manifestations of Leishmania spp. Infection. J. Neuroparasitol. 2011, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gureev, A.P.; Sadovnikova, I.S.; Popov, V.N. Molecular Mechanisms of the Neuroprotective Effect of Methylene Blue. Biochemistry 2022, 87, 940–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Chen, L.L.; Zhuang, J.Y.; Ke, Q.F.; Xiao, D.R.; Lin, W.P. Methylene Blue Mitigates Acute Neuroinflammation after Spinal Cord Injury through Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Microglia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, J.G.; Martins, J.F.S.; Pereira, A.H.C.; Mittmann, J.; Raniero, L.J.; Ferreira-Strixino, J. Evaluation of Methylene Blue as Photosensitizer in Promastigotes of Leishmania major and Leishmania braziliensis. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2017, 18, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fall, B.; Madamet, M.; Diawara, S.; Briolant, S.; Wade, K.A.; Lo, G.; Nakoulima, A.; Fall, M.; Bercion, R.; Kounta, M.B.; et al. Ex vivo Activity of Proveblue, a Methylene Blue, against Field Isolates of Plasmodium falciparum in Dakar, Senegal from 2013–2015. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 50, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, J.; Sakane, K.K.; Bhattacharjee, T.; Pinto, J.G.; Ferreira, I.; Raniero, L.J.; Ferreira-Strixino, J. Evaluation of Photodynamic Therapy with Methylene Blue, by the Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) in Leishmania major—In vitro. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 207, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakane, K.K.; Bhattacharjee, T.; Fagundes, J.; Marcolino, L.M.C.; Ferreira, I.; Pinto, J.G.; Ferreira-Strixino, J. Biochemical Changes in Leishmania braziliensis after Photodynamic Therapy with Methylene Blue Assessed by the Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozlem-Caliskan, S.; Ertabaklar, H.; Bilgin, M.D.; Ertug, S. Evaluation of Photodynamic Therapy against Leishmania tropica Promastigotes Using Different Photosensitizers. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2022, 38, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aureliano, D.P.; Lindoso, J.A.L.; Soares, S.R.C.; Takakura, C.F.H.; Pereira, T.M.; Ribeiro, M.S. Cell Death Mechanisms in Leishmania amazonensis Triggered by Methylene Blue-Mediated Antiparasitic Photodynamic Therapy. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, F.V.; Sabino, C.P.; Dimmer, J.A.; Sauter, I.P.; Cortez, M.J.; Ribeiro, M.S. Preclinical Investigation of Methylene Blue-mediated Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy on Leishmania Parasites Using Real-Time Bioluminescence. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloi, L.S.; Biondo, C.E.G.; Kimura, E.; Politi, M.J.; Lonardoni, M.V.C.; Aristides, S.M.A.; Dorea, R.C.C.; Hioka, N.; Silveira, T.G.V. Photodynamic Therapy for American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: The Efficacy of Methylene Blue in Hamsters Experimentally Infected with Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 128, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Lindoso, J.A.L.; Oyafuso, L.K.; Kanashiro, E.H.Y.; Cardoso, J.L.; Uchoa, A.F.; Tardivo, J.P.; Baptista, M.S. Photodynamic Therapy Using Methylene Blue to Treat Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2011, 29, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamon-Reig, F.; Martí-Martí, I.; Loughlin, C.R.M.; Garcia, A.; Carrera, C.; Aguilera-Peiró, P. Successful Treatment of Facial Cutaneous Leishmaniasis with Photodynamic Therapy. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2022, 88, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iniguez, E.; Varela-Ramirez, A.; Martínez, A.; Torres, C.L.; Sánchez-Delgado, R.A.; Maldonado, R.A. Ruthenium-Clotrimazole Complex has Significant Efficacy in the Murine Model of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Acta Trop. 2016, 164, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.S.; Gonçalves, Y.G.; Nunes, D.C.O.; Napolitano, D.R.; Maia, P.I.S.; Rodrigues, R.S.; Rodrigues, V.M.; Von Poelhsitz, G.; Yoneyama, K.A.G. Anti-Leishmania Activity of New Ruthenium(II) Complexes: Effect on Parasite-Host Interaction. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017, 175, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, V.M.; Costa, M.S.; Guilardi, S.; Machado, A.E.H.; Ellena, J.A.; Tudini, K.A.G.; Von Poelhsitz, G. In vitro Leishmanicidal Activity and Theoretical Insights into Biological Action of Ruthenium(II) Organometallic Complexes Containing Anti-Inflammatories. BioMetals 2018, 31, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, N.R.F.; Aguiar, F.L.N.; Santos, C.F.; Costa, A.M.L.; Hardoim, D.J.; Calabrese, K.S.; Almeida-Souza, F.; Sousa, E.H.S.; Lopes, L.G.F.; Teixeira, M.J.; et al. In vitro and in vivo Leishmanicidal Activity of a Ruthenium Nitrosyl Complex against Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis. Acta Trop. 2019, 192, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valigurová, A.; Kolářová, I. Unrevealing the Mystery of Latent Leishmaniasis: What Cells Can Host Leishmania? Pathogens 2023, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes-Junior, R.A.; Silva, R.S.; Lima, R.G.; Vannier-Santos, M.A. Antifungal Mechanism of [RuIII(NH3)4catechol]+ Complex on Fluconazole-Resistant Candida tropicalis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 364, fnx073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, L.; Torres-Santos, E.C. Differents Aspects on Chemotherapy of Trypanosomatids; Nova Science Pub Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 1536108502. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C.C.; Zhang, H.; Batista, M.M.; Oliveira, G.M.; Demarque, K.C.; Silva, N.L.; Moreira, O.C.; Ogungbe, I.V.; Soeiro, M.D.N.C. Phenotypic Investigation of 4-Nitrophenylacetyl- and 4-Nitro-1H-Imidazoyl-Based Compounds as Antileishmanial Agents. Parasitology 2022, 149, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo-Lima, C.F.; Christoni, L.S.A.; Justo, G.; Soeiro, M.N.C.; Aiub, C.A.F.; Felzenszwalb, I. Atorvastatin Downregulates In vitro Methyl Methanesulfonate and Cyclophosphamide Alkylation-Mediated Cellular and DNA Injuries. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 7820890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottini, M.M.; Amaral, A.C.F.; Ferreira, J.L.P.; Oliveira, E.S.C.; Silva, J.R.A.; Taniwaki, N.N.; Santos, A.R.; Almeida-Souza, F.; Souza, C.S.F.; Calabrese, K.S. Endlicheria bracteolata (Meisn.) Essential Oil as a Weapon Against Leishmania amazonensis: In vitro Assay. Molecules 2019, 24, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanha, A.J.; Castro, S.L.; Soeiro, M.N.C.; Lannes-Vieira, J.; Ribeiro, I.; Talvani, A.; Bourdin, B.; Blum, B.; Olivieri, B.; Zani, C.; et al. In vitro and in vivo Experimental Models for Drug Screening and Development for Chagas Disease. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2010, 105, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Santos, C.; Meuser Batista, M.; Inam Ullah, A.; Rama Krishna Reddy, T.; Soeiro, M.D.N.C. Drug Screening Using Shape-Based Virtual Screening and in vitro Experimental Models of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Parasitology 2021, 148, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Nagarajan, A.; Uchil, P.D. Analysis of Cell Viability by the AlamarBlue Assay. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2018, 2018, pdb.prot095489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balanco, J.M.F.; Costa Moreira, M.E.; Bonomo, A.; Bozza, P.T.; Amarante-Mendes, G.; Pirmez, C.; Barcinski, M.A. Apoptotic Mimicry by an Obligate Intracellular Parasite Downregulates Macrophage Microbicidal Activity. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 1870–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanderley, J.L.M.; Damatta, R.A.; Barcinski, M.A. Apoptotic Mimicry as a Strategy for the Establishment of Parasitic Infections: Parasite- and Host-Derived Phosphatidylserine as Key Molecule. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanderley, J.L.M.; Silva, L.H.P.; Deolindo, P.; Soong, L.; Borges, V.M.; Prates, D.B.; Souza, A.P.A.; Barral, A.; Balanco, J.M.F.; Nascimento, M.T.C.; et al. Cooperation between Apoptotic and Viable Metacyclics Enhances the Pathogenesis of Leishmaniasis. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingärtner, A.; Kemmer, G.; Müller, F.D.; Zampieri, R.A.; Santos, M.G.; Schiller, J.; Pomorski, T.G. Leishmania Promastigotes Lack Phosphatidylserine but Bind Annexin V upon Permeabilization or Miltefosine Treatment. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridley, M. The Power of Parasites. In The Red Queen: Sex and the Evolution of Human Nature; Viking Books: London, UK, 1993; p. 310. ISBN 0-06-055657-9. [Google Scholar]

- Neuenschwander, A.; Rocha, V.P.C.; Bastos, T.M.; Marcourt, L.; Morin, H.; Rocha, C.Q.; Grimaldi, G.B.; Sousa, K.A.F.; Borges, J.N.; Rivara-Minten, E.; et al. Production of Highly Active Antiparasitic Compounds from the Controlled Halogenation of the Arrabidaea brachypoda Crude Plant Extract. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 2631–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, L.S.A.; Almeida-Souza, F.; Lopes, Y.S.C.; Novas, R.C.V.; Santos, K.B.A.; Ligiero, C.B.P.; Calabrese, K.S.; Buarque, C.D. Synthesis of 3-Aryl-4-(N-Aryl)Aminocoumarins via Photoredox Arylation and the Evaluation of their Biological Activity. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 114, 105141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortoleti, B.T.S.; Gonçalves, M.D.; Tomiotto-Pellissier, F.; Contato, V.M.; Silva, T.F.; Matos, R.L.N.; Detoni, M.B.; Rodrigues, A.C.J.; Carloto, A.C.; Lazarin, D.B.; et al. Solidagenone Acts on Promastigotes of L. amazonensis by Inducing Apoptosis-like Processes on Intracellular Amastigotes by IL-12p70/ROS/NO Pathway Activation. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Silva, J.V.; Moreira, R.F.; Watanabe, L.A.; Souza, C.S.F.; Hardoim, D.J.; Taniwaki, N.N.; Bertho, A.L.; Teixeira, K.F.; Cenci, A.R.; Doring, T.H.; et al. Monomethylsulochrin Isolated from Biomass Extract of Aspergillus sp. against Leishmania amazonensis: In vitro Biological Evaluation and Molecular Docking. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 974910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Silva, J.V.; Moragas-Tellis, C.J.; Chagas, M.S.S.; Souza, P.V.R.; Moreira, D.L.; Hardoim, D.J.; Taniwaki, N.N.; Costa, V.F.A.; Bertho, A.L.; Brondani, D.; et al. Carajurin Induces Apoptosis in Leishmania amazonensis Promastigotes through Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, J.; Passero, L.F.D.; Jesus, J.A.; Laurenti, M.D.; Lago, J.H.G.; Soares, M.G.; Batista, A.N.L.; Batista, J.M.; Sartorelli, P. Absolute Configuration and Antileishmanial Activity of (–)-Cyclocolorenone Isolated from Duguetia lanceolata (Annonaceae). Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 1626–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paes, S.S.; Silva-Silva, J.V.; Gomes, P.W.P.; Silva, L.O.; Costa, A.P.L.; Lopes Júnior, M.L.; Hardoim, D.J.; Moragas-Tellis, C.J.; Taniwaki, N.N.; Bertho, A.L.; et al. (-)-5-Demethoxygrandisin B a New Lignan from Virola Surinamensis (Rol.) Warb. Leaves: Evaluation of the Leishmanicidal Activity by in vitro and in silico Approaches. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago-Silva, K.M.; Bortoleti, B.T.S.; Oliveira, L.N.; Maia, F.L.A.; Castro, J.C.; Costa, I.C.; Lazarin, D.B.; Wardell, J.L.; Wardell, S.M.S.V.; Albuquerque, M.G.; et al. Antileishmanial Activity of 4,8-Dimethoxynaphthalenyl Chalcones on Leishmania amazonensis. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Silva, K.M.; Bortoleti, B.T.S.; Brito, T.O.; Costa, I.C.; Lima, C.H.S.; Macedo, F.; Miranda-Sapla, M.M.; Pavanelli, W.R.; Bispo, M.L.F. Exploring the Antileishmanial Activity of N1, N2-Disubstituted-Benzoylguanidines: Synthesis and Molecular Modeling Studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 11495–11510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, P.G.; Bortoleti, B.T.S.; Fabris, M.; Gonçalves, M.D.; Tomiotto-Pellissier, F.; Costa, I.N.; Conchon-Costa, I.; Lima, C.H.S.; Pavanelli, W.R.; Bispo, M.L.F.; et al. Thiohydantoins as Anti-Leishmanial Agents: In vitro Biological Evaluation and Multi-Target Investigation by Molecular Docking Studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 3213–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.S.C.; Santos, V.S.; Devereux, M.; McCann, M.; Santos, A.L.S.; Branquinha, M.H. The Anti-Leishmania amazonensis and Anti-Leishmania chagasi Action of Copper(II) and Silver(I) 1,10-Phenanthroline-5,6-Dione Coordination Compounds. Pathogens 2023, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maquiaveli, C.C.; Silva, E.R.; Jesus, B.H.; Monteiro, C.E.O.; Navarro, T.R.; Branco, L.O.P.; Santos, I.S.; Reis, N.F.; Portugal, A.B.; Wanderley, J.L.M.; et al. Design and Synthesis of New Anthranyl Phenylhydrazides: Antileishmanial Activity and Structure–Activity Relationship. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes-Alves, A.G.; Duarte, M.; Cruz, T.; Castro, H.; Lopes, F.; Moreira, R.; Ressurreição, A.S.; Tomás, A.M. Biological Evaluation and Mechanistic Studies of Quinolin-(1H)-Imines as a New Chemotype against Leishmaniasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e01513-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Present, C.; Girão, R.D.; Lin, C.; Caljon, G.; Van Calenbergh, S.; Moreira, O.; Ruivo, L.A.S.; Batista, M.M.; Azevedo, R.; Batista, D.G.J.; et al. N6-Methyltubercidin Gives Sterile Cure in a Cutaneous Leishmania amazonensis Mouse Model. Parasitology 2024, 151, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roquero, I.; Cantizani, J.; Cotillo, I.; Manzano, M.P.; Kessler, A.; Martín, J.J.; McNamara, C.W. Novel Chemical Starting Points for Drug Discovery in Leishmaniasis and Chagas Disease. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2019, 10, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.A.A.; Junior, C.O.R.; Martinez, P.D.G.; Koovits, P.J.; Soares, B.M.; Ferreira, L.L.G.; Michelan-Duarte, S.; Chelucci, R.C.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Galuppo, M.K.; et al. 2-Aminobenzimidazoles for Leishmaniasis: From Initial Hit Discovery to in vivo Profiling. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsuno, K.; Burrows, J.N.; Duncan, K.; Van Huijsduijnen, R.H.; Kaneko, T.; Kita, K.; Mowbray, C.E.; Schmatz, D.; Warner, P.; Slingsby, B.T. Hit and Lead Criteria in Drug Discovery for Infectious Diseases of the Developing World. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Uzonna, J.E. The Early Interaction of Leishmania with Macrophages and Dendritic Cells and Its Influence on the Host Immune Response. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, G.A.; Descoteaux, A. Macrophage Cytokines: Involvement in Immunity and Infectious Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, J.P.; Saraiva, E.M.; Rocha-Azevedo, B. The Site of the Bite: Leishmania Interaction with Macrophages, Neutrophils and the Extracellular Matrix in the Dermis. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atri, C.; Guerfali, F.Z.; Laouini, D. Role of Human Macrophage Polarization in Inflammation during Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A. Comparative Trials of Antimonial Drugs in Urinary Schistosomiasis. Bull. World Health Organ. 1968, 38, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saad, K.A.; Abdalla, I.O.; Alkailani, H.A.; Elbakush, A.M.; Zreiba, Z.A. Evaluation of Hepatotoxicity Effect of Sodium Stibogluconate (Pentostam) in Mice Model. Al-Mukhtar J. Sci. 2022, 37, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.L.L.; Brustoloni, Y.M.; Fernandes, T.D.; Dorval, M.E.C.; Cunha, R.V.; Bóia, M.N. Severe Adverse Reactions to Meglumine Antimoniate in the Treatment of Visceral Leishmaniasis: A Report of 13 Cases in the Southwestern Region of Brazil. Trop. Doct. 2009, 39, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhshan, A.; Kamel, B.R.; Saffaei, A.; Tavakoli-Ardekani, M. Hepatotoxicity Induced by Azole Antifungal Agents: A Review Study. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2023, 22, e130336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abajo, F.J.; Carcas, A.J. Fixed Drug Eruption Associated with DM Iadce Pa Anonsm. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1986, 293, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Fanos, V.; Cataldi, L. Amphotericin B-Induced Nephrotoxicity: A Review. J. Chemother. 2000, 12, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deray, G.; Mercadal, L.; Bagnis, C. Amphotericin B Nephrotoxicity. Nephrologie 2002, 23, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, G.P.; Crank, C.W.; Leikin, J.B. An Evaluation of Hepatotoxicity and Nephrotoxicity of Liposomal Amphotericin B (L-AMB). J. Med. Toxicol. 2011, 7, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, S.; Schwartz, R.A.; Patil, A.; Grabbe, S.; Goldust, M. Treatment Options for Leishmaniasis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcgwire, B.S.; Satoskar, A.R. Leishmaniasis: Clinical Syndromes and Treatment. QJM Int. J. Med. 2014, 107, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhavalkar, S.; Masengu, A.; O’Rourke, D.; Shields, J.; Courtney, A. Nebulized Pentamidine-Induced Acute Renal Allograft Dysfunction. Case Rep. Transplant. 2013, 2013, 907593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.P.S.; Viçosa, A.L.; Ré, M.I.; Ricci-Júnior, E.; Holandino, C. A Review of Current Treatments Strategies Based on Paromomycin for Leishmaniasis. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.; Jha, T.K.; Thakur, C.P.; Engel, J.; Sindermann, H.; Fischer, C.; Junge, K.; Bryceson, A.; Berman, J. Oral Miltefosine for Indian Visceral Leishmaniasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olliaro, P.L.; Guerin, P.J.; Gerstl, S.; Haaskjold, A.A.; Rottingen, J.A.; Sundar, S. Treatment Options for Visceral Leishmaniasis: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies Done in India, 1980–2004. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minodier, P.; Jurquet, A.L.; Noël, G.; Uters, M.; Laporte, R.; Garnier, J.M. Le Traitement Des Leishmanioses. Arch. Pediatr. 2010, 17, 838–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarty, J.; Sundar, S. Current and Emerging Medications for the Treatment of Leishmaniasis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2019, 20, 1251–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castell, J.V.; Jover, R.; Martínez-Jiménez, C.P.; Gómez-Lechón, M.J. Hepatocyte Cell Lines: Their Use, Scope and Limitations in Drug Metabolism Studies. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2006, 2, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzumanian, V.A.; Kiseleva, O.I.; Poverennaya, E.V. The Curious Case of the HepG2 Cell Line: 40 Years of Expertise. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, H.; King, E.F.B.; Doleckova, K.; Bartholomew, B.; Hollinshead, J.; Mbye, H.; Ullah, I.; Walker, K.; Van Veelen, M.; Abou-Akkada, S.S.; et al. Temperate Zone Plant Natural Products—A Novel Resource for Activity against Tropical Parasitic Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, I.A.C.; De Paula, R.C.; Alves, C.L.; Faria, K.F.; Oliveira, M.M.; Takarada, G.G.M.; Dias, E.M.F.A.; Oliveira, A.B.; Silva, S.M. In Vitro Efficacy of Isoflavonoids and Terpenes against Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum and L. amazonensis. Exp. Parasitol. 2022, 242, 108383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabelova, A.; Kozics, K.; Kapka-Skrzypczak, L.; Kruszewski, M.; Sramkova, M. Nephrotoxicity: Topical Issue. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2019, 845, 402988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluta, K.; Jeleń, M.; Morak-Młodawska, B.; Zimecki, M.; Artym, J.; Kocięba, M.; Zaczyńska, E. Azaphenothiazines—Promising Phenothiazine Derivatives. An Insight into Nomenclature, Synthesis, Structure Elucidation and Biological Properties. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 138, 774–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcante-Costa, V.S.; Costa-Reginaldo, M.; Queiroz-Oliveira, T.; Oliveira, A.C.S.; Couto, N.F.; Dos Anjos, D.O.; Lima-Santos, J.; Andrade, L.O.; Horta, M.F.; Castro-Gomes, T. Leishmania amazonensis Hijacks Host Cell Lysosomes Involved in Plasma Membrane Repair to Induce Invasion in Fibroblasts. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs226183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yektaeian, N.; Zare, S.; Radfar, A.H.; Hatam, G. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide-Labeled Leishmania major can be Traced in Fibroblasts. J. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 2023, 7628912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Davis, S.; López-Arencibia, A.; Bethencourt-Estrella, C.J.; Nicolás-Hernández, D.S.; Viveros-Valdez, E.; Díaz-Marrero, A.R.; Fernández, J.J.; Lorenzo-Morales, J.; Piñero, J.E. Laurequinone, a Lead Compound against Leishmania. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parise-Filho, R.; Pasqualoto, K.F.M.; Magri, F.M.M.; Ferreira, A.K.; Silva, B.A.V.G.; Damião, M.C.F.C.B.; Tavares, M.T.; Azevedo, R.A.; Auada, A.V.V.; Polli, M.C.; et al. Dillapiole as Antileishmanial Agent: Discovery, Cytotoxic Activity and Preliminary SAR Studies of Dillapiole Analogues. Arch. Pharm. 2012, 345, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sá, G.C.S.; Silva, L.B.; Bezerra, P.V.V.; Silva, M.A.F.; Inacio, C.L.S.; Paiva, W.S.; Macedo e Silva, V.P.; Cordeiro, L.V.; Oliveira, J.W.F.; Silva, M.S.; et al. Tephrosia toxicaria (Sw.) Pers. Extracts: Screening by Examining Aedicidal Action under Laboratory and Field Conditions along with Its Antioxidant, Antileishmanial, and Antimicrobial Activities. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0275835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermiano, M.H.; Neves, A.R.; Silva, F.; Barros, M.S.A.; Vieira, C.B.; Stein, A.L.; Frizon, T.E.A.; Braga, A.L.; Arruda, C.C.P.; Parisotto, E.B.; et al. Selenium-Containing (Hetero)Aryl Hybrids as Potential Antileishmanial Drug Candidates: In vitro Screening against L. amazonensis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, S.F.P.; Alves, É.V.P.; Ferreira, R.S.; Fradico, J.R.B.; Lage, P.S.; Duarte, M.C.; Ribeiro, T.G.; Júnior, P.A.S.; Romanha, A.J.; Tonini, M.L.; et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of the Antiparasitic Activity of Bis-(Arylmethylidene) Cycloalkanones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 71, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, S.G.; Siqueira, L.A.; Zanini, M.S.; Matos, A.P.S.; Quaresma, C.H.; Silva, L.M.; Andrade, S.F.; Severi, J.A.; Villanova, J.C.O. Physicochemical and in vitro Biological Evaluations of Furazolidone-Based β-Cyclodextrin Complexes in Leishmania amazonensis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2018, 119, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.M.B.; Silva, A.R.S.T.; Santos, A.J.; Galvão, J.G.; Andrade-Neto, V.V.; Torres-Santos, E.C.; Ueki, M.M.; Almeida, L.E.; Sarmento, V.H.V.; Dolabella, S.S.; et al. Thermosensitive System Formed by Poloxamers Containing Carvacrol: An Effective Carrier System against Leishmania amazonensis. Acta Trop. 2023, 237, 106744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, F.V.; Riahi, M.; Persheyev, S.; Lian, C.; Cortez, M.; Samuel, I.D.W.; Ribeiro, M.S. Photodynamic Therapy Offers a Novel Approach to Managing Miltefosine-Resistant Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 116881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbeghen, M.R.; Voltarelli, E.M.; Campois, T.G.; Kimura, E.; Aristides, S.M.A.; Hernandes, L.; Caetano, W.; Hioka, N.; Lonardoni, M.V.C.; Silveira, T.G.V. Topical and Intradermal Efficacy of Photodynamic Therapy with Methylene Blue and Light-Emitting Diode in the Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania braziliensis. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 6, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Trahamane, E.J.O.; Monteiro, J.; Santos, G.P.; Crugeira, P.; Sampaio, F.; Oliveira, C.; Neto, M.B.; Pinheiro, A. Leishmanicidal Effect of Antiparasitic Photodynamic Therapy—ApPDT on Infected Macrophages. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1959–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, R.A.F.N.; Navasconi, T.R.; Reis, V.N.; Hioka, N.; Becker, T.C.A.; Lonardoni, M.V.C.; Aristides, S.M.A.; Silveira, T.G.V. Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment of American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis: Evaluation of Therapies Association in Experimentally Infected Mice with Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 9, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, F.V.; Yoshimura, T.M.; Silva, D.F.T.; Cortez, M.; Ribeiro, M.S. Photodynamic Therapy Mediated by a Red LED and Methylene Blue Inactivates Resistant Leishmania amazonensis. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2023, 40, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannier-Santos, M.; De Castro, S. Electron Microscopy in Antiparasitic Chemotherapy: A (Close) View to a Kill. Curr. Drug Targets 2009, 10, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannier-Santos, M.A.; Martiny, A.; Lins, U.; Urbina, J.A.; Borges, V.M.; Souza, W. Impairment of Sterol Biosynthesis Leads to Phosphorus and Calcium Accumulation in Leishmania Acidocalcisomes. Microbiology 1999, 145, 3213–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vannier-Santos, M.A.; Lins, U. Cytochemical Techniques and Energy-Filtering Transmission Electron Microscopy Applied to the Study of Parasitic Protozoa. Biol. Proced. Online 2001, 3, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Hsu, F.; Scott, D.A.; Docampo, R.; Turk, J.; Beverley, S.M. Leishmania Salvage and Remodelling of Host Sphingolipids in Amastigote Survival and Acidocalcisome Biogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1566–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Abdel-Aziz, A.K.; Abdelfatah, S.; Abdellatif, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abel, S.; Abeliovich, H.; Abildgaard, M.H.; Abudu, Y.P.; Acevedo-Arozena, A.; et al. Guidelines for the Use and Interpretation of Assays for Monitoring Autophagy (4th Edition). Autophagy 2021, 17, 1–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwah, S.S.; Uzonna, J.E.; Ghavami, S. Assessment of Autophagy in Leishmania Parasites. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, A.; Carreon, T.; Iniguez, E.; Anzellotti, A.; Sánchez, A.; Tyan, M.; Sattler, A.; Herrera, L.; Maldonado, R.A.; Sánchez-Delgado, R.A. Searching for New Chemotherapies for Tropical Diseases: Ruthenium–Clotrimazole Complexes Display High in vitro Activity against Leishmania major and Trypanosoma cruzi and Low Toxicity toward Normal Mammalian Cells. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3867–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandzloch, M.; Arriaga, J.M.M.; Sánchez-Moreno, M.; Wojtczak, A.; Jezierska, J.; Sitkowski, J.; Wiśniewska, J.; Salas, J.M.; Łakomska, I. Strategies for Overcoming Tropical Disease by Ruthenium Complexes with Purine Analog: Application against Leishmania spp. and Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017, 176, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, J.C.M.; Carregaro, V.; Costa, D.L.; Silva, J.S.; Cunha, F.Q.; Franco, D.W. Antileishmanial Activity of Ruthenium(II)Tetraammine Nitrosyl Complexes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 4180–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmuller, P.; Bras-Gonçalves, R.; Lemesre, J.L. Phenotypical Characteristics, Biochemical Pathways, Molecular Targets and Putative Role of Nitric Oxide-Mediated Programmed Cell Death in Leishmania. Parasitology 2006, 132, S19–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tfouni, E.; Truzzi, D.R.; Tavares, A.; Gomes, A.J.; Figueiredo, L.E.; Franco, D.W. Biological Activity of Ruthenium Nitrosyl Complexes. Nitric Oxide—Biol. Chem. 2012, 26, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, T.M.; Kawakami, N.Y.; Panis, C.; Thomazelli, A.P.F.D.S.; Tomiotto-Pellissier, F.; Cataneo, A.H.D.; Kian, D.; Yamauchi, L.M.; Júnior, F.S.G.; Lopes, L.G.D.F.; et al. Antileishmanial Activity and Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Activation by RuNO Complex. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 2631625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olekhnovitch, R.; Bousso, P. Induction, Propagation, and Activity of Host Nitric Oxide: Lessons from Leishmania Infection. Trends Parasitol. 2015, 31, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.S.; Gonçalves, Y.G.; Teixeira, S.C.; Nunes, D.C.O.; Lopes, D.S.; Silva, C.V.; Silva, M.S.; Borges, B.C.; Silva, M.J.B.; Rodrigues, R.S.; et al. Increased ROS Generation Causes Apoptosis-like Death: Mechanistic Insights into the Anti-Leishmania Activity of a Potent Ruthenium(II) Complex. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2019, 195, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compounds | Antiparasitic Activity | Cytotoxicity/Selective Indexes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 μM | CC50 μM/(SIP/SIA) | ||||||

| Pro. | Ama. | L929 | HepG2 | VERO | J744.G8 | MPMs | |

| MB | 61.44 ± 4.41 | 15.65 ± 2.23 | 321.65 ± 3.74 | 95.96 ± 3.28 | 141.05 ± 5.58 | 206.20 ± 9.19 | 36.02 ± 3.69 |

| (5.24/20.55) | (1.56/6.13) | (2.30/9.01) | (3.36/13.18) | (0.59/2.30) | |||

| NMB | 5.42 *** ± 0.81 | 2.66 ± 0.95 | 280.25 ± 2.19 | 71.56 ± 3.15 | 44.73 ± 3.40 | 68.50 ± 2.12 | 31.27 ± 5.72 |

| (51.71/105.35) | (13.20/26.90) | (8.25/16.82) | (12.64/25.75) | (5.77/11.76) | |||

| NMB-B | 5.48 *** ± 1.73 | 3.16 ± 0.37 | 270.30 ± 8.48 | 34.24 ± 7.31 | 247.95 ± 32.88 | 129.80 ± 7.35 | 65.91 ± 1.69 |

| (49.32/85.54) | (6.25/10.84) | (45.25/78.47) | (23.69/41.08) | (12.03/20.86) | |||

| NMB-P | 2.84 *** ± 0.80 | 0.46 ± 0.34 | 150.40 ± 12.02 | 35.05 ± 2.08 | 239.80 ± 27.57 | 69.82 ± 10.38 | 71.63 ± 1.85 |

| (52.96/326.96) | (12.34/76.20) | (84.44/521.30) | (24.58/151.78) | (25.22/155.72) | |||

| Miltefosine | 23.20 ± 2.55 | 0.97 ± 0.40 | 112.71 ± 18.22 | 181.00 ± 11.31 | 168.05 ± 2.75 | 155.60 ± 8.48 | 102.93 ± 4.77 |

| (4.86/116.20) | (7.80/186.60) | (7.24/173.25) | (6.71/160.41) | (4.44/106.11) | |||

| Compounds | IC50 (µM) | Promastigotes | IC50 (µM) | ex vivo Amastigotes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Population | High Population | Low Population | High Population | |||||||

| MFI | VIΔΨm | MFI | VIΔΨm | MFI | VIΔΨm | MFI | VIΔΨm | |||

| MB | 61.44 | 2737.60 * | −0.41 ± 0.05 | 56,878.47 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 15.65 | 3237.43 | −0.37 ± 0.32 | 317,106.50 | −0.61 ± 0.18 |

| NMB | 5.42 | 4095.05 | −0.14 ± 0.20 | 65,590.87 | 0.11 ± 0.08 | 2.66 | 3770.37 | −0.27 ± 0.06 | 277,557.80 * | −0.43 ± 0.20 |

| NMB-B | 5.48 | 4070.50 | −0.13 ± 0.09 | 74,562.13 | 0.27 ± 0.16 | 3.16 | 4174.80 | −0.31 ± 0.03 | 410,112.30 | −0.59 ± 0.21 |

| NMB-P | 2.84 | 3359.03 * | −0.28 ± 0.03 | 86,029.23 | 0.49 ± 0.36 | 0.46 | 7215.47 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 642,051.43 | 0.39 ± 0.13 |

| Control | - | 4702.03 | 0.00 | 59,161.87 | 0.00 | - | 5226.50 | 0.00 | 469,563.43 | 0.00 |

| Compounds | IC50 (µM) | Promastigotes | IC50 (µM) | Ex Vivo Amastigotes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Population | High Population | Low Population | High Population | |||||||

| MFI | VIROS | MFI | VIROS | MFI | VIROS | MFI | VIROS | |||

| MB | 61.44 | 26,534.03 | 0.74 ± 0.12 | 1,658,186.80 * | 3.56 ± 0.50 | 15.65 | 3151.50 | 1.28 ± 0.46 | 140,636.20 | 0.90 ± 0.29 |

| NMB | 5.42 | 31,489.80 | 0.87 ± 0.12 | 1,512,521.00 * | 3.61 ± 0.08 | 2.66 | 2940.57 | 1.62 ± 0.90 | 131,669.43 | 0.84 ± 0.51 |

| NMB-B | 5.48 | 39,191.97 | 1.06 ± 0.11 | 2,639,177.00 ** | 5.81 ± 0.64 | 3.16 | 2116.87 | 1.11 ± 0.48 | 131,896.27 | 0.85 ± 0.49 |

| NMB-P | 2.84 | 34,607.80 | 1.02 ± 0.48 | 2,325,902.50 ** | 5.39 ± 1.83 | 0.46 | 3063.17 | 1.27 ± 0.45 | 140,291.57 | 0.90 ± 0.45 |

| AA | 10 | 19,775.40 | 0.52 ± 0.13 | 890,705.80 | 2.07 ± 0.23 | 10 | 3011.23 | 1.14 ± 0.38 | 143,227.25 | 0.60 ± 0.53 |

| Control | - | 39,868.50 | - | 452,909.35 | - | - | 2436.40 | - | 158,240.00 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vasco-dos-Santos, D.R.; Almeida-Silva, J.; Fiuza, L.F.d.A.; Vacani-Martins, N.; Rocha, Z.N.d.; Soeiro, M.d.N.C.; Henriques-Pons, A.; Torres-Santos, E.C.; Vannier-Santos, M.A. From Dyes to Drugs? Selective Leishmanicidal Efficacy of Repositioned Methylene Blue and Its Derivatives in In Vitro Evaluation. Biology 2025, 14, 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121709

Vasco-dos-Santos DR, Almeida-Silva J, Fiuza LFdA, Vacani-Martins N, Rocha ZNd, Soeiro MdNC, Henriques-Pons A, Torres-Santos EC, Vannier-Santos MA. From Dyes to Drugs? Selective Leishmanicidal Efficacy of Repositioned Methylene Blue and Its Derivatives in In Vitro Evaluation. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121709

Chicago/Turabian StyleVasco-dos-Santos, Deyvison Rhuan, Juliana Almeida-Silva, Ludmila Ferreira de Almeida Fiuza, Natalia Vacani-Martins, Zênis Novais da Rocha, Maria de Nazaré Correia Soeiro, Andrea Henriques-Pons, Eduardo Caio Torres-Santos, and Marcos André Vannier-Santos. 2025. "From Dyes to Drugs? Selective Leishmanicidal Efficacy of Repositioned Methylene Blue and Its Derivatives in In Vitro Evaluation" Biology 14, no. 12: 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121709

APA StyleVasco-dos-Santos, D. R., Almeida-Silva, J., Fiuza, L. F. d. A., Vacani-Martins, N., Rocha, Z. N. d., Soeiro, M. d. N. C., Henriques-Pons, A., Torres-Santos, E. C., & Vannier-Santos, M. A. (2025). From Dyes to Drugs? Selective Leishmanicidal Efficacy of Repositioned Methylene Blue and Its Derivatives in In Vitro Evaluation. Biology, 14(12), 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121709