Effects of Preventive Exposure to High Doses of Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) on Testicular and Sperm Alterations Caused by Scrotal Heat Shock in Mice

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Animals

2.2. ALA Administration and Acute Testicular Degeneration by HS

2.3. Genital Tract Collection and Gonadosomatic/Glandular Index

2.4. Sperm Collection and Analysis

2.4.1. Sperm Kinematics

2.4.2. Sperm Concentration and Morphology

2.4.3. Hypoosmotic Test (HOST)

2.4.4. Structural Integrity of Membranes

2.4.5. Chromatin Assessment Test

2.5. Testicular Histomorphometry and Histopathology

2.6. Radioimmunoassay (RIA) for Testosterone

2.7. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Survival Rate After Scrotal Heat Shock (HS) Bath

3.2. Body Mass, Testosterone, and Genital Tract Mass

3.3. Testicular Volumetric Density

3.4. Sperm Kinematics and Morphology

3.5. Structural and Functional Integrity of Membranes, and Sperm DNA Compaction

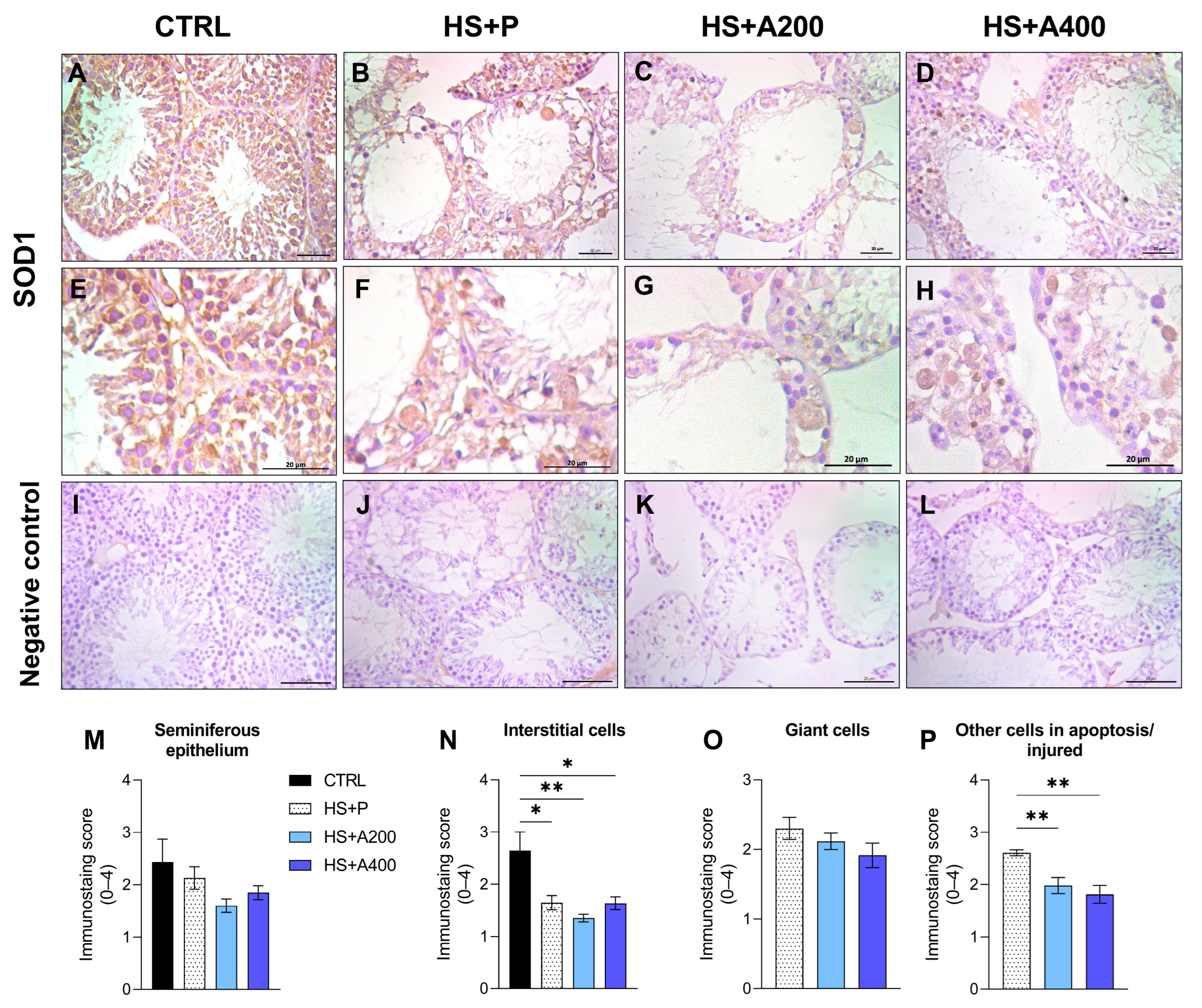

3.6. Immunostaining of SOD1 in the Testis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALA | Alpha-lipoic acid |

| HS | Heat shock |

| CTRL | Control group |

| VSL | Linear progressive velocity |

| STR | Straightness |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| SOD1 | Superoxide dismutase 1 |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| DHLA | Dihydrolipoic acid |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| LaBIO | Laboratory of Animal Breeding, Maintenance, and Experimentation |

| UESC | Santa Cruz State University |

| ARRIVE | Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments |

| CEUA | Ethics Committee on Animal Use |

| I.P. | Intraperitoneal |

| TM | Total motility |

| PM | Progressive motility |

| VCL | Curvilinear velocity |

| VAP | Average path velocity |

| LIN | Linearity |

| ALH | Amplitude of lateral head displacement |

| HOST | Hypoosmotic test |

| CFDA | Carboxyfluorescein diacetate |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| SCA | Sperm class analyzer |

| RIA | Radioimmunoassay |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| DM2500 | Leica DM2500 Microscope |

| DFC 295 | Leica DFC 295 Digital Camera |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| Shapiro-Wilk | Shapiro–Wilk normality test |

| Kruskal-Wallis | Kruskal–Wallis test |

| Dunn | Dunn multiple comparison test |

| GI | Glandular index |

| TB | Toluidine blue |

| TB+ | Toluidine blue positive |

| TB− | Toluidine blue negative |

| HSP70 | Heat shock protein 70 |

| HSP90 | Heat shock protein 90 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| GSH/GSSG | Reduced/oxidized glutathione ratio |

Appendix A

| CONTROL | HS + P | HS + A200 | HS + A400 | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-Value | p-Value | |||||

| Acrosome defects | 2.52 ± 0.90 | 3.60 ± 1.33 | 6.57 ± 1.85 | 4.00 ± 1.29 | 1.32 | 0.290 |

| Head defects | 10.83 ± 2.52 | 12.80 ± 2.47 | 10.57 ± 1.88 | 12.17 ± 2.00 | 0.22 | 0.880 |

| Isolated head | 8.66 ± 3.36 | 3.55 ± 0.55 | 3.71 ± 1.30 | 7.33 ± 2.37 | 1.81 | 0.171 |

| Tail | 0.50 ± 0.22 | 1.10 ± 0.45 | 0.71 ± 0.28 | 1.60 ± 1.16 | 0.61 | 0.610 |

| Cytoplasmic droplet | 8.50 ± 1.43 b | 21.00 ± 3.26 a | 15.00 ± 3.42 ab | 21.00 ± 3.76 ab | 3.40 | 0.035 |

| Midpiece | 9.00 ± 0.85 | 13.11 ± 3.33 | 10.71 ± 2.90 | 12.67 ± 2.41 | 0.43 | 0.731 |

| Main piece | 17.50 ± 3.73 | 12.60 ± 2.87 | 12.57 ± 2.33 | 8.33 ± 1.83 | 1.41 | 0.262 |

| End piece | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.50 ± 0.26 | 0.57 ± 0.42 | 0.66 ± 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.593 |

References

- Levine, H.; Jørgensen, N.; Martino-Andrade, A.; Mendiola, J.; Weksler-Derri, D.; Jolles, M.; Pinotti, R.; Swan, S.H. Temporal Trends in Sperm Count: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis of Samples Collected Globally in the 20th and 21st Centuries. Hum. Reprod. Update 2023, 29, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, N.; Lamb, D.J.; Levine, H.; Pastuszak, A.W.; Sigalos, J.T.; Swan, S.H.; Eisenberg, M.L. Are Worldwide Sperm Counts Declining? Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 1457–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durairajanayagam, D.; Sharma, R.K.; Plessis, S.S.; Agarwal, A. Testicular Heat Stress and Sperm Quality. In Male Infertility: A complete Guide to Lifestyle and Environmental Factor; Springer Science and Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 105–125. ISBN 9781493910403. [Google Scholar]

- Kastelic, J.P. Thermoregulation of the Testes. In Bovine Reproduction; Hopper, R.M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 26–29. ISBN 9781118833971. [Google Scholar]

- Durairajanayagam, D.; Agarwal, A.; Ong, C. Causes, Effects and Molecular Mechanisms of Testicular Heat Stress. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2015, 30, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahat, A.M.; Rizzoto, G.; Kastelic, J.P. Amelioration of Heat Stress-Induced Damage to Testes and Sperm Quality. Theriogenology 2020, 158, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanter, M.; Aktas, C.; Erboga, M. Heat Stress Decreases Testicular Germ Cell Proliferation and Increases Apoptosis in Short Term: An Immunohistochemical and Ultrastructural Study. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2013, 29, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R.M.O. Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management of Testicular Degeneration in Stallions. Clin. Tech. Equine Pract. 2007, 6, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dare, B.J.; Oyeniyi, F.; Olaniyan, T. Role of Antioxidant in Testicular Integrity. Annu. Res. Rev. Biol. 2014, 4, 998–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, M.; Kodama, H.; Fukuda, J.; Shimizu, Y.; Murata, M.; Kumagai, J.; Tanaka, T. Role of Radical Oxygen Species in Rat Testicular Germ Cell Apoptosis Induced by Heat Stress. Biol. Reprod. 1999, 61, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zheng, Y.; Lv, Y.; Li, F.; Su, L.; Qin, Y.; Zeng, W. Melatonin Protects the Mouse Testis against Heat-Induced Damage. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 26, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikim, A.P.S.; Lue, Y.; Yamamoto, C.M.; Vera, Y.; Rodriguez, S.; Yen, P.H.; Soeng, K.; Wang, C.; Swerdloff, R.S. Key Apoptotic Pathways for Heat-Induced Programmed Germ Cell Death in the Testis. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 3167–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, C.; Teng, S.; Saunders, P.T.K. A Single, Mild, Transient Scrotal Heat Stress Causes Hypoxia and Oxidative Stress in Mouse Testes, Which Induces Germ Cell Death1. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 80, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Milne, S.; Leeson, H. Sperm DNA Damage Caused by Oxidative Stress: Modifiable Clinical, Lifestyle and Nutritional Factors in Male Infertility. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2014, 28, 684–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, L.; Ghibu, S.; Richard, C.; Zeller, M.; Cottin, Y.; Vergely, C. Direct and Indirect Antioxidant Properties of α-Lipoic Acid and Therapeutic Potential. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, L.; Witt, E.H.; Tritschler, H.J. Alpha-Lipoic Acid as a Biological Antioxidant. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 19, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moini, H.; Packer, L.; Saris, N.E.L. Antioxidant and Prooxidant Activities of α-Lipoic Acid and Dihydrolipoic Acid. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2002, 182, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. The Effects and Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Nutrient α-Lipoic Acid on Improving Age-Associated Mitochondrial and Cognitive Dysfunction: An Overview. Neurochem. Res. 2008, 33, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khabbazi, T.; Mahdavi, R.; Safa, J.; Pour-Abdollahi, P. Effects of Alpha-Lipoic Acid Supplementation on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Serum Lipid Profile Levels in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease on Hemodialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 2012, 22, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, A.; Mazooji, N.; Roozbeh, J.; Mazloom, Z.; Hasanzade, J. Effect of Alpha-Lipoic Acid and Vitamin E Supplementation on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Malnutrition in Hemodialysis Patients. Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 2013, 7, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, F.; Dehghani, M.A.; Vanani, A.R.; Mahdavinia, M. Protective Effects of Alpha Lipoic Acid Against Arsenic Induced Oxidative Stress in Isolated Rat Liver Mitochondria. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mancy, E.M.; Elsherbini, D.M.A.; Al-Serwi, R.H.; El-Sherbiny, M.; Ahmed Shaker, G.; Abdel-Moneim, A.M.H.; Enan, E.T.; Elsherbiny, N.M. α-Lipoic Acid Protects against Cyclosporine A-Induced Hepatic Toxicity in Rats: Effect on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis. Toxics 2022, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaakur, S.; Himabindhu, G. Effect of Alpha Lipoic Acid on the Tardive Dyskinesia and Oxidative Stress Induced by Haloperidol in Rats. J. Neural Transm. 2009, 116, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibska, B.; Goraca, A.; Skibska, A.; Stanczak, A. Effect of Alpha-Lipoic Acid on Rat Ventricles and Atria under LPS-Induced Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Zhai, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Fu, C.; Zhu, M. Alpha Lipoic Acid Inhibits Oxidative Stress-Induced Apoptosis by Modulating of Nrf2 Signalling Pathway after Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 4088–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.C.; Lai, Y.S.; Chou, T.C. The Protective Effect of Alpha-Lipoic Acid in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury Is Mediated by Heme Oxygenase-1. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 590363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpag, H.; Gül, M.; Aydemir, Y.; Atilla, N.; Yiğitcan, B.; Cakir, T.; Polat, C.; Þehirli, Ö.; Sayan, M. Protective Effects of Alpha-Lipoic Acid on Methotrexate-Induced Oxidative Lung Injury in Rats. J. Investig. Surg. 2018, 31, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.F.; Osman, I.K.; Srijit, I.I.; Iii, D.; Othman, A.M. A Study of the Antioxidant Effect of Alpha Lipoic Acids on Sperm Quality. Clinics 2008, 64, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, L.B.N.S.; Costa, C.A.S.; Ribas, J.A.S.; Boaventura, G.T.; Chagas, M.A. Antioxidant Action of Alpha Lipoic Acid on the Testis and Epididymis of Diabetic Rats: Morphological, Sperm and Immunohistochemical Evaluation. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2019, 45, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaygannia, E.; Rahimi, M.; Tavalaee, M.; Akhavanfarid, G.R.; Dattilo, M. Alpha-Lipoic Acid Improves the Testicular Dysfunction in Rats Induced by Varicocele. Andrologia 2018, 50, e13085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbal, S.; Ergur, B.U.; Erbil, G.; Tekmen, I.; Bagrıyanık, A.; Cavdar, Z. The Effects of α-Lipoic Acid against Testicular Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 489248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pınar, N.; Çakırca, G.; Özgür, T.; Kaplan, M. The Protective Effects of Alpha Lipoic Acid on Methotrexate Induced Testis Injury in Rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 1486–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem Guzel, E.; Kaya Tektemur, N.; Tektemur, A. Alpha-Lipoic Acid May Ameliorate Testicular Damage by Targeting Dox-Induced Altered Antioxidant Parameters, Mitofusin-2 and Apoptotic Gene Expression. Andrologia 2021, 53, e13990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashour, A.E.; Abdel-Hamied, H.E.; Korashy, H.M.; Al-Shabanah, O.A.; Abd-Allah, A.R.A. Alpha-Lipoic Acid Rebalances Redox and Immune-Testicular Milieu in Septic Rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2011, 189, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prathima, P.; Venkaiah, K.; Pavani, R.; Daveedu, T.; Munikumar, M.; Gobinath, M.; Valli, M.; Sainath, S.B. A-Lipoic Acid Inhibits Oxidative Stress in Testis and Attenuates Testicular Toxicity in Rats Exposed to Carbimazole During Embryonic Period. Toxicol. Rep. 2017, 4, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohasseb, M.; Ebied, S.; Yehia, M.A.H.; Hussein, N. Testicular Oxidative Damage and Role of Combined Antioxidant Supplementation in Experimental Diabetic Rats. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 67, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepa, P.; Dal Lago, A.; De Leo, C.; Gallo, M.; Rizzo, C.; Licata, E.; Anserini, P.; Rago, R.; Scaruffi, P. Combined Treatment with Myo-Inositol, Alpha-Lipoic Acid, Folic Acid and Vitamins Significantly Improves Sperm Parameters of Sub-Fertile Men: A Multi-Centric Study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 7078–7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Yin, Q.; Li, J.; He, S. Oxidative Stress and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Are Involved in the Protective Effect of Alpha Lipoic Acid against Heat Damage in Chicken Testes. Animals 2020, 10, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusha’u, Y.; Muhammad, U.A.; Mustapha, S.; Umar, A.H.; Imam, M.I.; Umar, B.; Alhassan, A.W.; Saleh, M.I.; Ya’u, J. Alpha-Lipoic Acid Attenuates Depressive Symptoms in Mice Exposed to Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress. J. Afr. Assoc. Physiol. Sci. 2021, 9, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, X.; Maeda, N. α-Lipoic Acid Prevents the Increase in Atherosclerosis Induced by Diabetes in Apolipoprotein E—Deficient Mice Fed High-Fat/Low-Cholesterol Diet. Diabetes 2006, 55, 2238–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, M.; Abuyassin, B.; Golbidi, S.; Ayas, N.; Laher, I. Alpha Lipoic Acid Improves Endothelial Function and Oxidative Stress in Mice Exposed to Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 4093018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenouchi, Y.; Tsuboi, K.; Ohsuka, K.; Nobe, K.; Ohtake, K.; Okamoto, Y.; Kasono, K. Chronic Treatment with α-Lipoic Acid Improves Endothelium-Dependent Vasorelaxation of Aortas in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 42, 1456–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhao, J. jun Alpha-Lipoic Acid Attenuates Insulin Resistance and Improves Glucose Metabolism in High Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2014, 35, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, S.C. Common Vehicles for Nonclinical Evaluation of Therapeutic Agents. In Drug Safety Evaluation; Gad, S.C., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1140–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Yon, J.; Kim, J.S.; Lin, C.; Park, S.G.; Gwon, L.W.; Lee, J.; Baek, I.; Nahm, S.; Nam, S.; Kim, J.S.; et al. Beta-Carotene Prevents the Spermatogenic Disorders Induced by Exogenous Scrotal Hyperthermia through Modulations of Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis, and Androgen Biosynthesis in Mice. Korean J. Vet. Res. 2019, 59, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colégio Brasileiro de Reprodução. Animal Manual Para Exame Andrológico e Avaliação de Sêmen Animal, 3rd ed.; Colégio Brasileiro de Reprodução Animal: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2013; ISBN 978-85-85584-05-04. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, N.; Yoshinaga, K.; Furushima, K.; Takamune, K.; Li, Z.; Abe, S.I.; Aizawa, S.I.; Yamamura, K.I. Viable Offspring Obtained from Prm1-Deficient Sperm in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, N.H.C.; Zain, H.H.M.; Ibrahim, H.; Jamil, N.N.M. Evaluation of Acute and Sub-Acute Oral Toxicity Effect of Aquilaria Malaccensis Leaves Aqueous Extract in Male ICR Mice. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2019, 25, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B.M.; Rathje, C.C.; Bacon, J.; Johnson, E.E.P.; Larson, E.L.; Kopania, E.E.K.; Good, J.M.; Yousafzai, G.; Affara, N.A.; Ellis, P.J.I. A High-Throughput Method for Unbiased Quantitation and Categorization of Nuclear Morphology. Biol. Reprod. 2019, 100, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.; Zhao, X.L.; Yang, J.; Hu, S.F.; Lei, H.; Xia, W.; Zhu, C.H. Effect of Transient Scrotal Hyperthermia on Sperm Parameters, Seminal Plasma Biochemical Markers, and Oxidative Stress in Men. Asian J. Androl. 2015, 17, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, R.A.P.; Vickers, S.E. Use of Fluorescent Probes to Assess Membrane Integrity in Mammalian Spermatozoa. Reproduction 1990, 88, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naves, C.S.; Beletti, M.E.; Duarte, M.B.; Vieira, R.C. Avaliação Da Cromatina Espermática Em Eqüinos Com Azul De Toluidina E “Acridine Orange”. Biosci. J. 2004, 20, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, F.C.R.; Martins, A.L.P.; de Melo, F.C.S.A.; Cupertino, M.d.C.; Gomes, M.d.L.M.; de Oliveira, J.M.; Damasceno, E.M.; Silva, J.; Otoni, W.C.; da Matta, S.L.P. Hydroalcoholic Extract of Pfaffia Glomerata Alters the Organization of the Seminiferous Tubules by Modulating the Oxidative State and the Microstructural Reorganization of the Mice Testes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 233, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, S.G. Testicular Biopsy Score Count—A Method for Registration of Spermatogeneses in Humnan Testes: Normal Values and Results in 335 Hypogonadal Males. Hormones 1970, 1, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, M.; Khambata-Ford, S.; Copie-Bergman, C.; Huang, L.; Juco, J.; Hofman, V.; Hofman, P. Correction: Use of the 22C3 Anti-PD-L1 Antibody to Determine PD-L1 Expression in Multiple Automated Immunohistochemistry Platforms. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelko, I.N.; Mariani, T.J.; Folz, R.J. Superoxide Dismutase Multigene Family: A Comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) Gene Structures, Evolution, and Expression. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.C.; Cordeiro, J.M.d.A.; Cunha, M.C.d.S.G.; Santos, B.R.; Oliveira, L.S.D.; Silva, A.L.d.; Barbosa, E.M.; Niella, R.V.; de Freitas, G.J.C.; Santos, D.D.A.; et al. Kisspeptin-10 Improves Testicular Redox Status but Does Not Alter the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) That Is Downregulated by Hypothyroidism in a Rat Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Malyar, R.M.; Ye, N.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Shi, F.; Li, Y. Alpha-Lipoic Acid Alleviates Lead-Induced Testicular Damage in Roosters by Reducing Oxidative Stress and Modulating Key Pathways. Toxics 2025, 13, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashandy, S.A.; Morsy, F.A.; Bashandy, Y.S.; Elbaset, M.A.; Mohamed, B.M.S.A. Alpha-Lipoic Acid Alleviates Testicular Dysfunction Induced by Olanzapine in Male Rats, Involvement of Adiposity, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Male Hormonal Factors. Pharmacol. Res.-Rep. 2025, 3, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, T.N.; Van, P.D.; Cong, T.D.; Le Minh, T.; Vu, Q.H.N. Assessment of Testis Histopathological Changes and Spermatogenesis in Male Mice Exposed to Chronic Scrotal Heat Stress. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2020, 8, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Thanh, T.; Dang-Van, P.; Dang-Ngoc, P.; Kim, W.; Le-Minh, T.; Nguyen-Vu, Q.-H. Chronic Scrotal Heat Stress Causes Testicular Interstitial Inflammation and Fibrosis: An Experimental Study in Mice. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2022, 20, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockett, J.C.; Mapp, F.L.; Garges, J.B.; Luft, J.C.; Mori, C.; Dix, D.J. Effects of Hyperthermia on Spermatogenesis, Apoptosis, Gene Expression, and Fertility in Adult Male Mice. Biol. Reprod. 2001, 65, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, G.C.D.; Oliveira, V.V.G.; Gueiros, O.G.; Torres, S.M.; Maia, F.C.L.; Tenorio, B.M.; Morais, R.N.; Junior, V.A.S.; Queiroz, G.C.D.; Oliveira, V.V.G.; et al. Effect of Pentoxifylline on the Regeneration of Rat Testicular Germ Cells after Heat Shock. Anim. Reprod. 2018, 10, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.H.; Huang, K.H.; Tian, Y.F.; Lin, C.H.; Chao, C.M.; Tang, L.Y.; Hsieh, K.L.; Chang, C.P. Exertional Heat Stroke on Fertility, Erectile Function, and Testicular Morphology in Male Rats. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, A.; Qureshi, A.S.; Shahid, R.U.; Hussain, M.; Usman, M.; Umar, Z. Maintenance of Thermal Homeostasis with Special Emphasis on Testicular Thermoregulation. Acta Vet. Eurasia 2019, 45, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Sengupta, P.; Slama, P.; Roychoudhury, S. Oxidative Stress, Testicular Inflammatory Pathways, and Male Reproduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, X.; Li, H. Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress-Induced Sperm Dysfunction. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1520835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, P. Male Genital Tract. In Histopathology of Preclinical Toxicity Studies; Elsevier: London, UK, 2012; pp. 1–10. ISBN 9780444538567. [Google Scholar]

- Creasy, D.; Bube, A.; de Rijk, E.; Kandori, H.; Kuwahara, M.; Masson, R.; Nolte, T.; Reams, R.; Regan, K.; Rehm, S.; et al. Proliferative and Nonproliferative Lesions of the Rat and Mouse Male Reproductive System. Toxicol. Pathol. 2012, 40, 40–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lirdi, L.C.; Stumpp, T.; Sasso-Cerri, E.; Miraglia, S.M. Amifostine Protective Effect on Cisplatin-Treated Rat Testis. Anat. Rec. Adv. Integr. Anat. Evol. Biol. 2008, 291, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohamy, H.G.; Lebda, M.A.; Sadek, K.M.; Elfeky, M.S.; El-Sayed, Y.S.; Samak, D.H.; Hamed, H.S.; Abouzed, T.K. Biochemical, Molecular and Cytological Impacts of Alpha-Lipoic Acid and Ginkgo Biloba in Ameliorating Testicular Dysfunctions Induced by Silver Nanoparticles in Rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 38198–38211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.I.; El-Missiry, M.A.; Koriem, K.M.; El-Sayed, A.A. Alfa-Lipoic Acid Protects Testosterone Secretion Pathway and Sperm Quality against 4-Tert-Octylphenol Induced Reproductive Toxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 81, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang-Cong, T.; Nguyen-Thanh, T.; Dang-Cong, T.; Nguyen-Thanh, T. Testicular Histopathology and Spermatogenesis in Mice with Scrotal Heat Stress. In Male Reproductive Anatomy; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Emam, M.M.; Ray, M.N.; Ozono, M.; Kogure, K. Heat Stress Disrupts Spermatogenesis via Modulation of Sperm-Specific Calcium Channels in Rats. J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 112, 103465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Ren, B. Effects of a Mild Heat Treatment on Mouse Testicular Gene Expression and Sperm Quality. Animal Cells Syst. 2010, 14, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capela, L.; Leites, I.; Romão, R.; Lopes-Da-costa, L.; Pereira, R.M.L.N. Impact of Heat Stress on Bovine Sperm Quality and Competence. Animals 2022, 12, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, A.; Aghajanpour, F.; Soltani, R.; Vafaei-Nezhad, S.; Ezi, S.; Azad, N.; Aliaghaei, A.; Fridoni, M.J.; Tavakoli, N.; Abdollahifar, M.A.; et al. Upregulation of Heat Shock Proteins 70 and 90 Induced by Transient Scrotal Hyperthermia in Mice. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2025, 29, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaeipour, S.; Piryaei, A.; Aliaghaei, A.; Nazarian, H.; Naserzadeh, P.; Ebrahimi, V.; Abdi, S.; Shahi, F.; Ahmadi, H.; Fadaei Fathabadi, F.; et al. Chronic Scrotal Hyperthermia Induces Azoospermia and Severe Damage to Testicular Tissue in Mice. Acta Histochem. 2021, 123, 151712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, S.; King, S.A.; Irvine, D.S.; Saunders, P.T.K. Impact of a Mild Scrotal Heat Stress on DNA Integrity in Murine Spermatozoa. Reproduction 2005, 129, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, B.J.; Nixon, B.; Martin, J.H.; De Iuliis, G.N.; Trigg, N.A.; Bromfield, E.G.; McEwan, K.E.; Aitken, R.J. Heat Exposure Induces Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in the Male Germ Line. Biol. Reprod. 2018, 98, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Xu, Y.; Mao, C.; Wang, Z.; Guo, S.; Jin, X.; Yan, S.; Shi, B. Effects of Heat Stress on Antioxidant Status and Immune Function and Expression of Related Genes in Lambs. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, D.R.; Rabeler, R.; Roberts, A.; Lynch, B. Safety Evaluation of α-Lipoic Acid (ALA). Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006, 46, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DTU Food. Safety of Alpha-Lipoic Acid Use in Food Supplements; DTU Food: Lyngby, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, S.A.; Price, T.O.; Banks, W.A.; Ercal, N.; Morley, J.E. Effect of Alpha-Lipoic Acid on Memory, Oxidation, and Lifespan in SAMP8 Mice. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2012, 32, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CTRL | HS + P | HS + A200 | HS + A400 | p-Value (ANOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seminiferous tubules | 85.48 ± 1.19 a | 79.11 ± 3.16 a | 59.61 ± 2.36 b | 78.87 ± 1.81 a | <0.0001 |

| Tunica propria | 9.16 ± 0.48 a | 5.28 ± 0.90 b | 5.09 ± 0.48 b | 4.23 ± 0.54 b | <0.0001 |

| Seminiferous epithelium | 60.01 ± 2.42 a | 46.18 ± 2.79 b | 36.14 ± 1.42 c | 46.92 ± 2.56 b | <0.0001 |

| Lumen | 16.31 ± 1.32 b | 27.64 ± 1.38 a | 18.39 ± 2.10 b | 27.71 ± 1.70 a | <0.001 |

| Intertubular compartment | 14.52 ± 1.19 b | 20.89 ± 3.16 b | 40.39 ± 2.63 a | 21.13 ± 1.81 b | <0.0001 |

| Leydig cell | 3.60 ± 0.37 ab | 4.18 ± 0.29 a | 2.77 ± 0.18 b | 3.80 ± 0.46 ab | 0.0341 |

| Blood vessels | 1.02 ± 0.23 a | 1.12 ± 0.19 a | 0.88 ± 0.19 a | 1.46 ± 0.10 a | 0.1788 |

| Lymphatic space | 6.48 ± 1.61 b | 10.76 ± 2.20 b | 33.75 ± 2.35 a | 12.26 ± 1.83 b | <0.0001 |

| Connective tissue | 3.43 ± 0.75 a | 4.83 ± 1.23 a | 2.98 ± 0.41 a | 3.61 ± 0.32 a | 0.5268 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, L.C.; Kersul, M.G.; Machado, W.M.; Cordeiro, J.M.d.A.; Santos, B.R.; Oliveira, C.L.; Oliveira, C.S.; Santana, L.R.; Silva, J.F.; Snoeck, P.P.d.N. Effects of Preventive Exposure to High Doses of Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) on Testicular and Sperm Alterations Caused by Scrotal Heat Shock in Mice. Biology 2025, 14, 1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121708

Santos LC, Kersul MG, Machado WM, Cordeiro JMdA, Santos BR, Oliveira CL, Oliveira CS, Santana LR, Silva JF, Snoeck PPdN. Effects of Preventive Exposure to High Doses of Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) on Testicular and Sperm Alterations Caused by Scrotal Heat Shock in Mice. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121708

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Luciano Cardoso, Maíra Guimarães Kersul, William Morais Machado, Jeane Martinha dos Anjos Cordeiro, Bianca Reis Santos, Cibele Luz Oliveira, Cleisla Souza Oliveira, Larissa Rodrigues Santana, Juneo Freitas Silva, and Paola Pereira das Neves Snoeck. 2025. "Effects of Preventive Exposure to High Doses of Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) on Testicular and Sperm Alterations Caused by Scrotal Heat Shock in Mice" Biology 14, no. 12: 1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121708

APA StyleSantos, L. C., Kersul, M. G., Machado, W. M., Cordeiro, J. M. d. A., Santos, B. R., Oliveira, C. L., Oliveira, C. S., Santana, L. R., Silva, J. F., & Snoeck, P. P. d. N. (2025). Effects of Preventive Exposure to High Doses of Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) on Testicular and Sperm Alterations Caused by Scrotal Heat Shock in Mice. Biology, 14(12), 1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121708