Analysis of Phenotypic Variability in Natural Populations of Cereus fernambucensis Lem. (Cactaceae)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

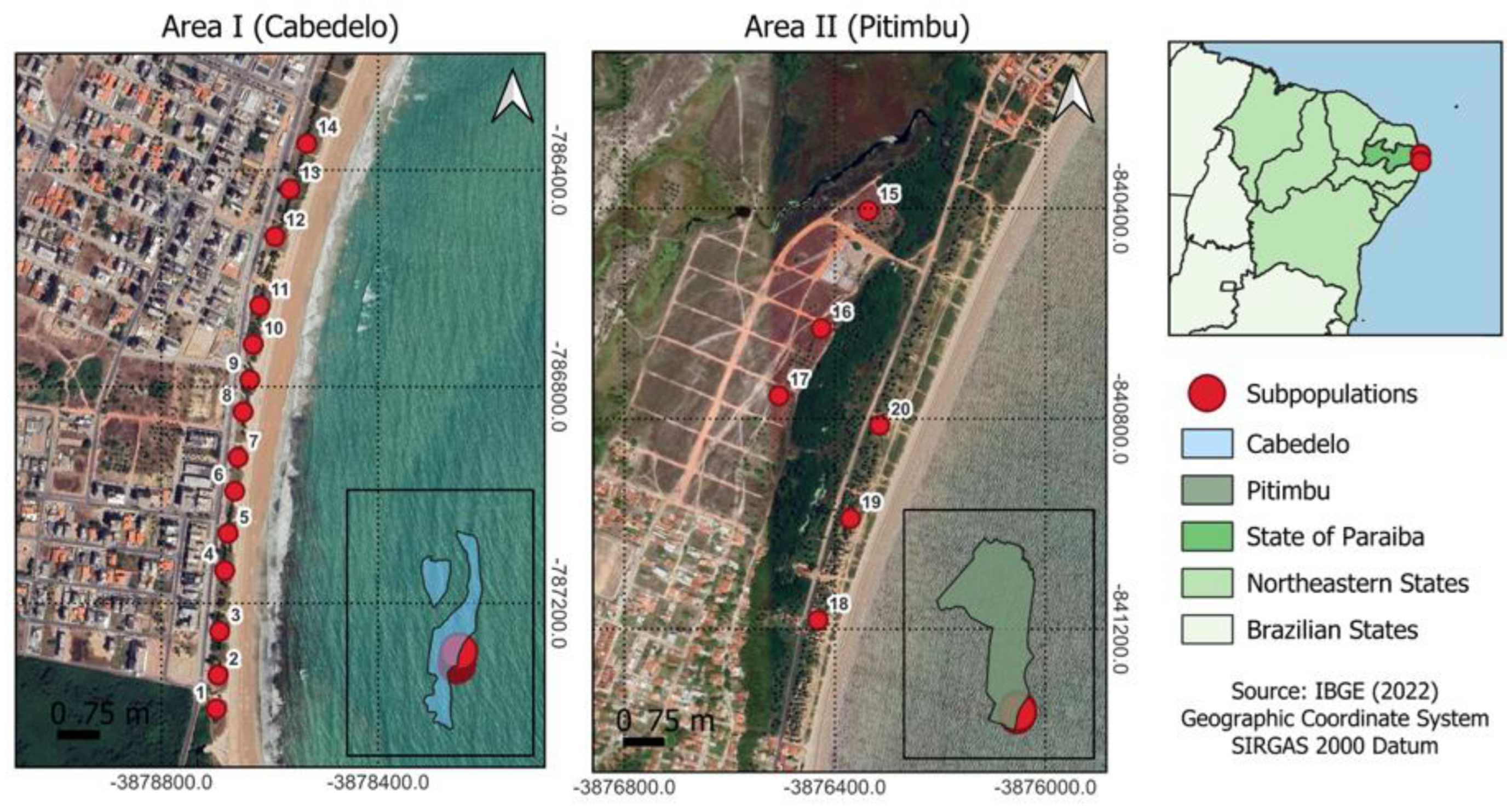

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Evaluated Traits

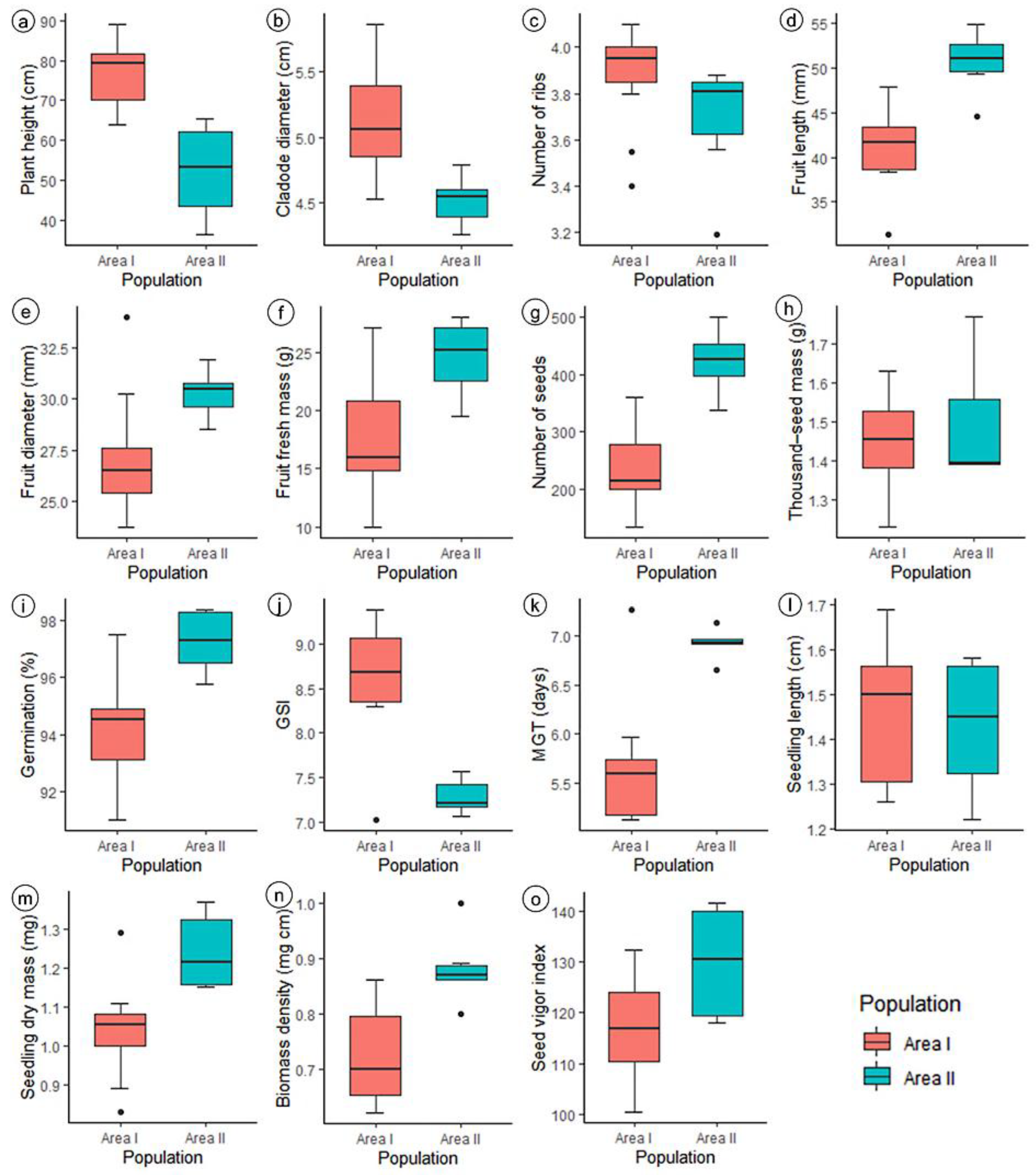

2.2.1. Characterization of the Vegetative Structure

2.2.2. Physical Traits of the Fruit

2.2.3. Physical and Physiological Characterization of Seeds

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

2.2.4. Seedling Performance

2.3. Data Design and Analysis

- (a)

- Phenotypic variance:

- (b)

- Environmental variance:

- (c)

- Genetic variance:

- (d)

- Broad-sense repeatability estimates:

- (e)

- Coefficient of genetic variation:

- (f)

- Coefficient of environmental variation:

- (g)

- Ratio

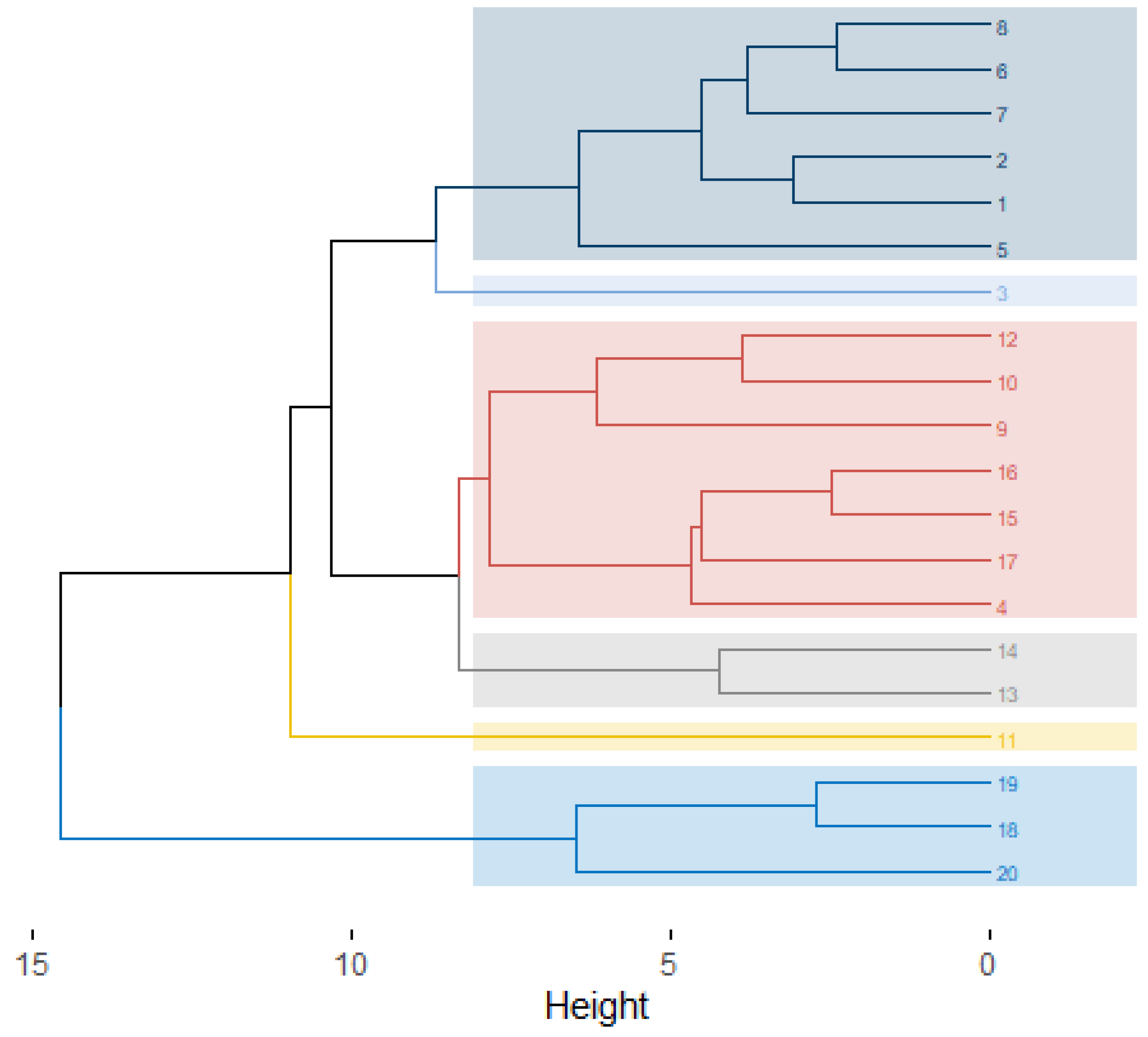

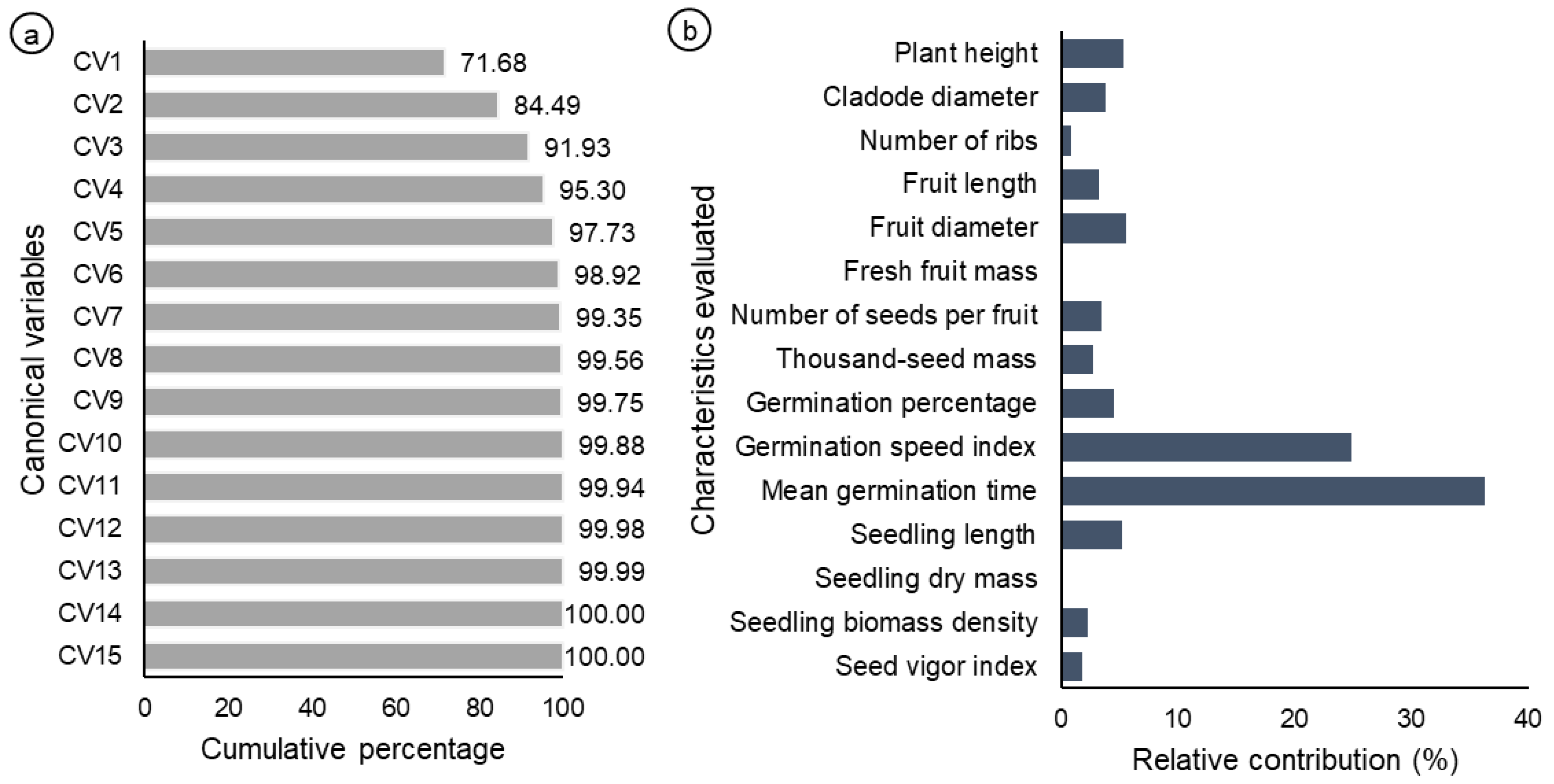

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAF | Brazilian Atlantic Forest |

| BOD | Biological oxygen demand |

| CAM | Crassulacean acid metabolism |

| CCA | Centro de Ciências Agrárias |

| CD | Cladode diameter |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| CVe | Environmental coefficient of variation |

| CVg | Genetic coefficient of variation |

| DEN | Biomass density |

| DFCA | Departamento de Fitotecnia e Ciências Ambientais |

| FD | Fruit diameter |

| FFM | Fruit fresh mass |

| FL | Fruit length |

| G% | Germination percentage |

| GSI | Germination speed index |

| IUCN | International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| MGT | Mean germination time |

| NR | Number of cladode ribs |

| NS | Number of seeds per fruit |

| PH | Plant height |

| RAPD | Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| SDM | Seedling dry mass |

| SL | Seedling length |

| SVI | Seed vigor index |

| TSM | Thousand-seed mass |

| UFPB | Universidade Federal da Paraíba |

| UPGMA | Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean |

References

- do Amaral, D.T.; Bonatelli, I.A.S.; Romeiro-Brito, M.; Moraes, E.M.; Franco, F.F. Spatial patterns of evolutionary diversity in Cactaceae show low ecological representation within protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 273, 109677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, F.F.; Silva, G.A.R.; Moraes, E.M.; Taylor, N.; Zappi, D.C.; Jojima, C.L.; Machado, M.C. Plio-Pleistocene diversification of Cereus (Cactaceae, Cereeae) and closely allied genera. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2017, 183, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Amaral, D.T.; Minhós-Yano, I.; Oliveira, J.V.M.; Romeiro-Brito, M.; Bonatelli, I.A.S.; Taylor, N.P.; Zappi, D.C.; Moraes, E.M.; Eaton, D.A.R.; Franco, F.F. Tracking the xeric biomes of South America: The spatiotemporal diversification of Mandacaru cactus. J. Biogeogr. 2021, 48, 3085–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombonato, J.R.; do Amaral, D.T.; Silva, G.A.R.; Khan, G.; Moraes, E.M.; Andrade, S.C.S.; Eaton, D.A.R.; Alonso, D.P.; Ribolla, P.E.M.; Taylor, N.; et al. The potential of genome-wide RAD sequences for resolving rapid radiations: A case study in Cactaceae. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2020, 151, 106896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.d. Anatomia Comparada dos Órgãos Florais de Cereus fernambucensis Lem. e Cereus hildmannianus K. Schum. (Cactaceae). Master’s Dissertation, Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp), São Vicente, SP, Brazil, 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.unesp.br/entities/publication/96372c54-a6f9-4942-a846-b7a5e4a7b382 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- do Amaral, D.T.; Bonatelli, I.A.S.; Romeiro-Brito, M.; Telhe, M.C.; Moraes, E.M.; Zappi, D.C.; Taylor, N.P.; Franco, F.F. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals lineage-and environment-specific adaptations in cacti from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Planta 2024, 260, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.D.; de Faria Pereira, S.M.; dos Reis Nunes, C.; de Oliveira, R.R.; de Oliveira, D.B. Atividade antioxidante, teor de taninos, fenóis, ácido ascórbico e açúcares em Cereus fernambucensis. Vértices 2015, 17, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, E.; Machado, I.C.S. Floral biology of Cereus fernambucensis: A sphingophilous cactus of restinga. Bradleya 1999, 1999, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, P.; Machado, M.; Taylor, N.P. Cereus fernambucensis . IUCN Red List. Threat. Species 2017, T152379A121471767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Amaral, D.T.; Oliveira, J.V.M.; Moraes, E.M.; Zappi, D.C.; Taylor, N.P.; Franco, F.F. The potential distribution of Cereus (Cactaceae) species in scenarios of climate crises. J. Arid Environ. 2025, 226, 105285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, C.J.; Nassar, J.M.; García-Rivas, A.E.; González-Carcacía, J.A. Population genetic diversity and structure of Pilosocereus tillianus (Cactaceae, Cereeae), a columnar cactus endemic to the Venezuelan Andes. J. Arid Environ. 2010, 74, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.D.; Ferreira, F.M.; Pessoni, L.A. Biometria Aplicada ao Estudo da Diversidade Genética, 2nd ed.; UFV: Viçosa, MG, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza, A.V.V.; Carvalho, J.R.d.S.; Costa, E.S.S.; de Souza, C.S.; Silva, H.F.d.J.; Luz, J.M.Q.; Maciel, G.M.; Siquieroli, A.C.S. Genetic diversity in Amburana (Amburana cearensis) accessions: Hierarchical and optimization methods. Rev. Árvore 2021, 45, e4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.N.; de Pádua, G.V.G.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Silva, J.H.C.S.; Bernardo, M.K.F.; Farias, G.E.S.; Gomes, C.L.S.; Alves, E.U. Caracterização morfofisiológica de frutos e sementes de espécies florestais: Um estudo de revisão. In Ciências Agrárias e Ambientais: Desafios e Perspectivas, 1st ed.; Abreu, K.G., da Silva, J.N., da Silva, J.M., da Silva, J.H.B., de Sousa, A.S., Santos, J.P.d.O., Eds.; Editora Itacaiúnas: Ananindeua, PA, Brazil, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.K.B.; de Morais, P.L.D.; Melo, N.J.d.A.; de Aragão, A.R.; Nunes, G.H.d.S.; Holanda, I.S.A.; Gurgel, E.P.; da Silva Neto, J.A. Genetic diversity among Tacinga inamoena (K Schum.) NP Taylor & Stuppy individuals. Braz. J. Bot. 2025, 48, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.N.d.; Pádua, G.V.G.d.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Silva, J.H.C.S.; Gomes, C.L.S.; Rodrigues, M.H.B.S.; Bernardo, M.K.F.; Silva, E.L.F.d.; Almeida, L.G.A.d.; Araújo, L.D.A.d.; et al. Fruits and seeds as indicators of the genetic diversity of Hymenaea martiana (Fabaceae) in Northeast Brazil. Biology 2025, 14, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MapBiomas. Plataforma MapBiomas—Cobertura e Uso da Terra do Brasil. Available online: https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Brasil. Regras Para Análise de Sementes; Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento: Brasília, Brazil; Secretaria de Defesa Agropecuária, MAPA/ACS: Brasília, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, J.O. Speed of germination and in selection and evaluation for seedling emergence and vigor. Crop Sci. 1962, 2, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labouriau, L.F.G. Germinação das Sementes; Secretaria da OEA: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, W.A.; Sávio, F.L.; Borém, A.; Dias, D.C.F.d.S. Influência da disposição, número e tamanho das sementes no teste de comprimento de plântulas de soja. Rev. Bras. Sementes 2009, 31, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abdul-Baki, A.A.; Anderson, J.D. Vigor determination in soybean by multiple criteria. Crop Sci. 1973, 13, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalanobis, P.C. On the generalized distance in statistics. Proc. Natl. Inst. Sci. India 1936, 2, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mojena, R. Hierarchical grouping methods and stopping rules: An evaluation. Comput. J. 1977, 20, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. The relative importance of characters affecting genetic divergence. Indian J. Genet. 1981, 41, 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, C.D.; Regazzi, A.J.; Carneiro, P.C.S. Modelos Biométricos Aplicados ao Melhoramento Genético, 3rd ed.; UFV: Viçosa, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, C.D. Genes Software-extended and integrated with the R, Matlab and Selegen. Acta Sci. Agron. 2016, 38, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Jelihovschi, E.G.; Faria, J.C.; Allaman, I.B. ScottKnott: A package for performing the Scott-Knott clustering algorithm in R. TEMA 2014, 15, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friendly, M.; Fox, J. candisc: Visualizing Generalized Canonical Discriminant and Canonical Correlation Analysis. R Package Version 0.9-0. 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=candisc (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Silva, A.R.; Azevedo, C.F. biotools: Tools for Biometry and Applied Statistics in Agricultural Science. R Package Version 4.3. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=biotools (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Kassambara, A. factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. R Package Version 1.0.7. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Moraes, E.M.; Abreu, A.G.; Andrade, S.C.S.; Sene, F.M.; Solferini, V.N. Population genetic structure of two columnar cacti with a patchy distribution in eastern Brazil. Genetica 2005, 125, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettsch, B.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Cruz-Piñón, G.; Duffy, J.P.; Frances, A.; Hernández, H.M.; Inger, R.; Pollock, C.; Schipper, J.; Superina, M.; et al. High proportion of cactus species threatened with extinction. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 15142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, J.L.; Godt, M.J.W.; Sherman-Broyles, S.L. Factors influencing levels of genetic diversity in woody plant species. New For. 1992, 6, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo, R.B.; Dardengo, J.d.F.E.; Bispo, R.B.; Bispo, R.B.; Rossi, A.A.B. Divergência genética entre genótipos de Mauritia flexuosa L. f. por meio de morfometria de frutos e sementes. Nativa 2020, 8, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.Y.B.d.O.; de Farias, S.G.G.; Araujo, P.C.D.; de Sousa, M.B.; Silva, R.B.; Oliveira, C.V.d.A. Genetic variability of Parkia platycephala populations: Support for defining seed collection areas. Rev. Caatinga 2022, 35, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, J.L.; Godt, M.J.W. Allozyme diversity in plant species. In Plant Population Genetics, Breeding and Genetic Resources; Brown, A.H.D., Clegg, M.T., Kahler, A.L., Weir, B.S., Eds.; Sinauer: Sunderland, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Roveri Neto, A.; de Paula, R.C. Variabilidade entre árvores matrizes de Ceiba speciosa St. Hil para características de frutos e sementes. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2017, 48, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdovinos, T.M.; de Paula, R.C. Diversidad genética de Handroanthus heptaphyllus a partir de calidad fisiológica de semillas. Bosque 2017, 38, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Silva, P.C.d.C.; Zanatto, B.; de Paula, R.C. Divergence among mother trees of Handroanthus serratifolius (Vahl) S. O. Grose regarding seed quality traits. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2023, 54, e20228428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, A.C.; Zuza, J.F.C.; Barbosa, L.d.S.; Azevedo, C.F.; Alves, E.U. Biometrics of mulungu seeds from different mother plants in the semi-arid region of Paraíba, Brazil. Rev. Caatinga 2022, 35, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Filho, J. Fisiologia de Sementes de Plantas Cultivadas, 2nd ed.; ABRATES: Londrina, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Salgotra, R.K.; Chauhan, B.S. Genetic diversity, conservation, and utilization of plant genetic resources. Genes 2023, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoban, S.; Campbell, C.D.; da Silva, J.M.; Ekblom, R.; Funk, W.C.; Garner, B.A.; Godoy, J.A.; Kershaw, F.; MacDonald, A.J.; Mergeay, J.; et al. Genetic diversity is considered important but interpreted narrowly in country reports to the Convention on Biological Diversity: Current actions and indicators are insufficient. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 261, 109233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, C.K.; Amariles, D.; Soto, J.S.; Diaz, M.V.; Sotelo, S.; Sosa, C.C.; Ramírez-Villegas, J.; Achicanoy, H.A.; Velásquez-Tibatá, J.; Guarino, L.; et al. Comprehensiveness of conservation of useful wild plants: An operational indicator for biodiversity and sustainable development targets. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, D.M.; Hendry, A.P.; Vázquez-Domínguez, E.; Friesen, V.L. Estimated six per cent loss of genetic variation in wild populations since the industrial revolution. Evol. Appl. 2019, 12, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoban, S.; Bruford, M.; Jackson, J.D.; Lopes-Fernandes, M.; Heuertz, M.; Hohenlohe, P.A.; Paz-Vinas, I.; Sjögren-Gulve, P.; Segelbacher, G.; Vernesi, C.; et al. Genetic diversity targets and indicators in the CBD post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework must be improved. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 248, 108654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.P.; Zappi, D.C.; Romeiro-Brito, M.; Telhe, M.C.; Franco, F.F.; Moraes, E.M. A phylogeny of Cereus (Cactaceae) and the placement and description of two new species. Taxon 2023, 72, 1321–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, M.M. Negotiating a fragmented world: What do we know, how do we know it, and where do we go from here? Diversity 2025, 17, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant Population | Municipality | Altitude (masl.) | Mean Temperature (min.–max.) (°C) | Mean Annual Precipitation (mm) | Landscape Conservation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area I | Cabedelo | 2.5 | 25.8 (22–30) | 1170 | Preserved restinga |

| Area II | Pitimbu | 2.5 | 25.9 (21–30) | 1165 | Anthropized restinga |

| Variation Factor | Mean Squares | ||||

| PH (cm) | CD (cm) | NR | FL (mm) | FD (mm) | |

| Genotypes | 856.78 ** | 0.78 ns | 0.3 ** | 136.38 * | 30.45 ns |

| Residue | 303.77 | 0.86 | 0.10 | 66.76 | 20.66 |

| h2 (%) | 64.54 | 0.0 | 63.88 | 51.04 | 32.14 |

| Ve | 75.94 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 16.69 | 5.16 |

| Vg | 138.25 | 0.0 | 0.04 | 17.40 | 2.44 |

| CVg/CVe | 0.67 | 0.0 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.34 |

| CV (%) | 25.12 | 18.87 | 8.54 | 18.58 | 16.27 |

| Variation Factor | Mean Squares | ||||

| FFM (g) | NS | TSM (g) | G (%) | GSI | |

| Genotypes | 118.85 ns | 46,075.81 * | 0.07 ** | 19.42 ** | 2.70 ** |

| Residue | 116.73 | 23251.43 | 0.007 | 8.59 | 0.15 |

| h2 (%) | 1.78 | 49.53 | 89.12 | 55.75 | 94.17 |

| Ve | 29.18 | 5812.85 | 0.0 | 2.14 | 0.03 |

| Vg | 0.53 | 5706.09 | 0.01 | 2.70 | 0.63 |

| CVg/CVe | 0.06 | 0.50 | 1.43 | 0.56 | 2.01 |

| CV (%) | 54.76 | 52.03 | 6.02 | 3.08 | 4.81 |

| Variation Factor | Mean Squares | ||||

| MGT (dias) | SL (cm) | SDM (mg) | DEN (cm mg−1) | SVI | |

| Genotypes | 2.37 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.04 ** | 544.28 ** |

| Residue | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 78.64 |

| h2 (%) | 96.20 | 83.42 | 79.59 | 74.73 | 85.55 |

| Ve | 0.02 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.66 |

| Vg | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 116.41 |

| CVg/CVe | 2.51 | 1.12 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.21 |

| CV (%) | 5.0 | 8.13 | 11.74 | 14.45 | 7.32 |

| Groups | Plant Subpopulations 1 |

|---|---|

| I | 15–16 |

| II | 2–7–8–4–6–5 |

| III | 13–14–12 |

| IV | 18–19 |

| V | 1–9 |

| VI | 3–17 |

| VII | 20 |

| VIII | 11 |

| IX | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, J.H.C.S.; Silva, J.N.d.; Souza, A.d.G.; Nascimento, N.F.F.d.; Alves, E.U. Analysis of Phenotypic Variability in Natural Populations of Cereus fernambucensis Lem. (Cactaceae). Biology 2025, 14, 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121702

Silva JHCS, Silva JNd, Souza AdG, Nascimento NFFd, Alves EU. Analysis of Phenotypic Variability in Natural Populations of Cereus fernambucensis Lem. (Cactaceae). Biology. 2025; 14(12):1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121702

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, João Henrique Constantino Sales, Joyce Naiara da Silva, Aline das Graças Souza, Naysa Flávia Ferreira do Nascimento, and Edna Ursulino Alves. 2025. "Analysis of Phenotypic Variability in Natural Populations of Cereus fernambucensis Lem. (Cactaceae)" Biology 14, no. 12: 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121702

APA StyleSilva, J. H. C. S., Silva, J. N. d., Souza, A. d. G., Nascimento, N. F. F. d., & Alves, E. U. (2025). Analysis of Phenotypic Variability in Natural Populations of Cereus fernambucensis Lem. (Cactaceae). Biology, 14(12), 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121702