Coumarin Inhibits Primary Root Growth by Modulating Auxin Signaling via Neddylation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

2.2. Cytological Observation and Tissue Staining

2.3. Gene Expression Analysis

2.4. Plant Transformation

2.5. Immunoblot Analysis

3. Results

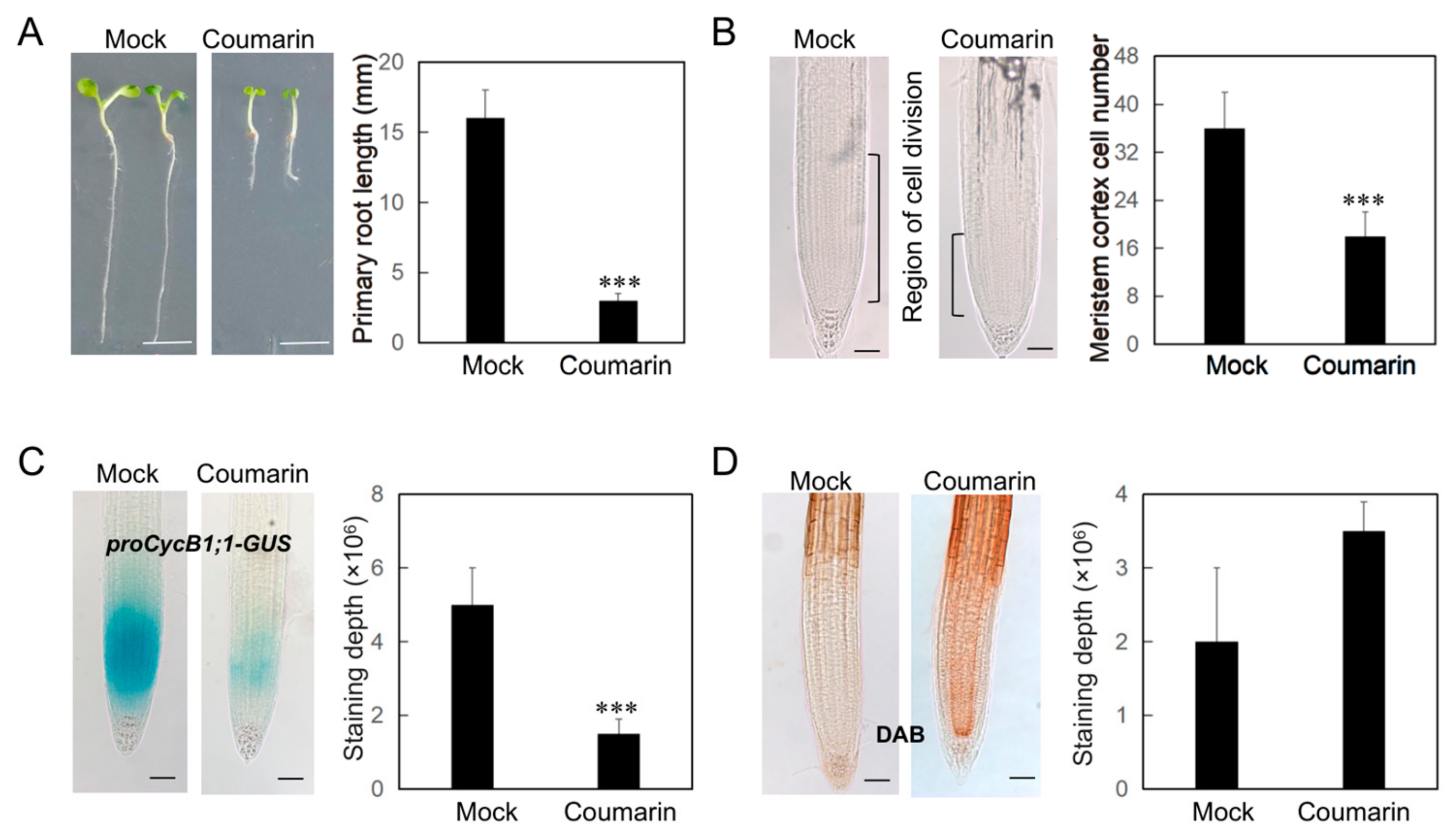

3.1. Coumarin Inhibits Primary Root Growth

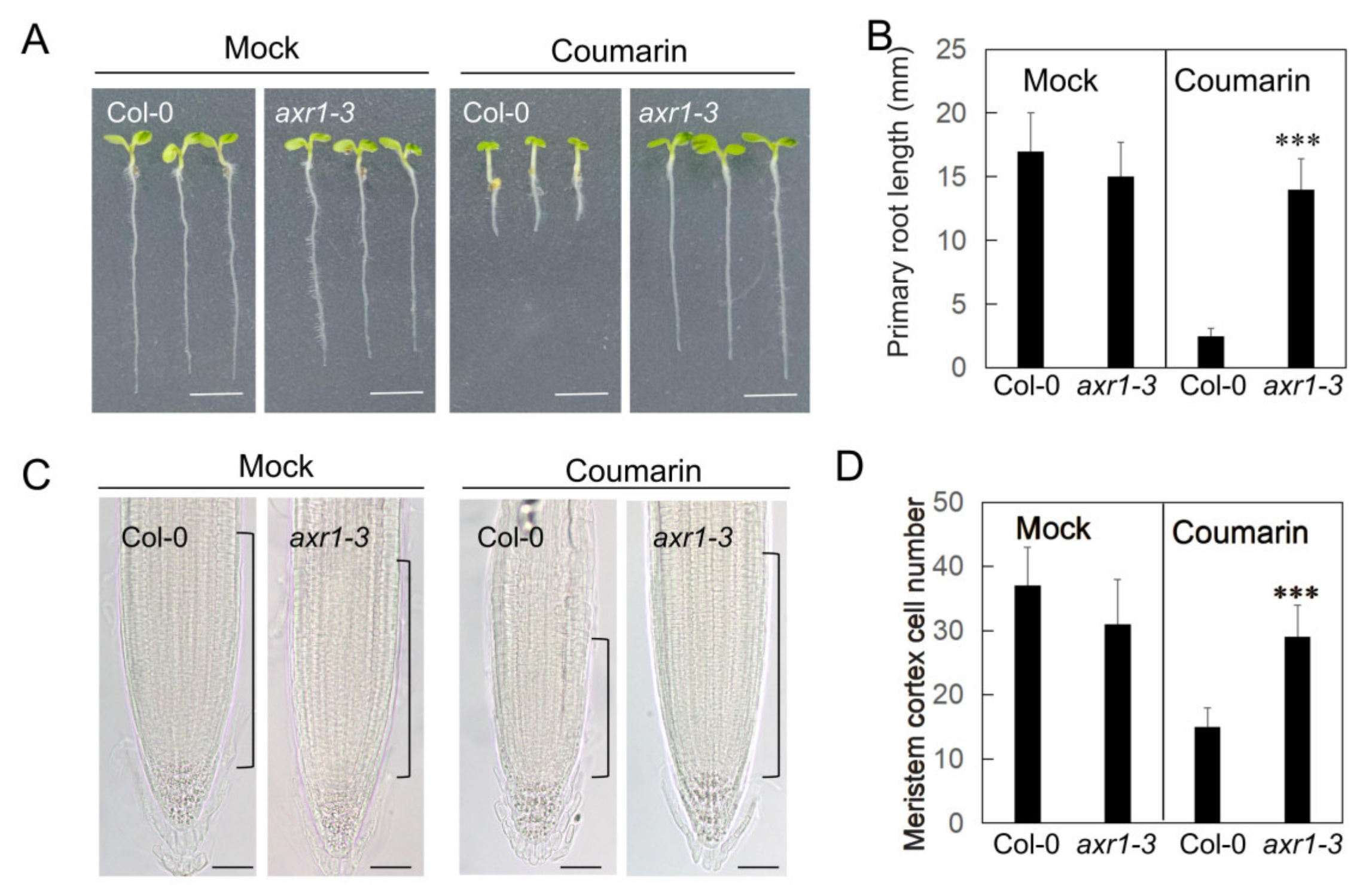

3.2. The AXR1 Mutation Confers Resistance to Coumarin

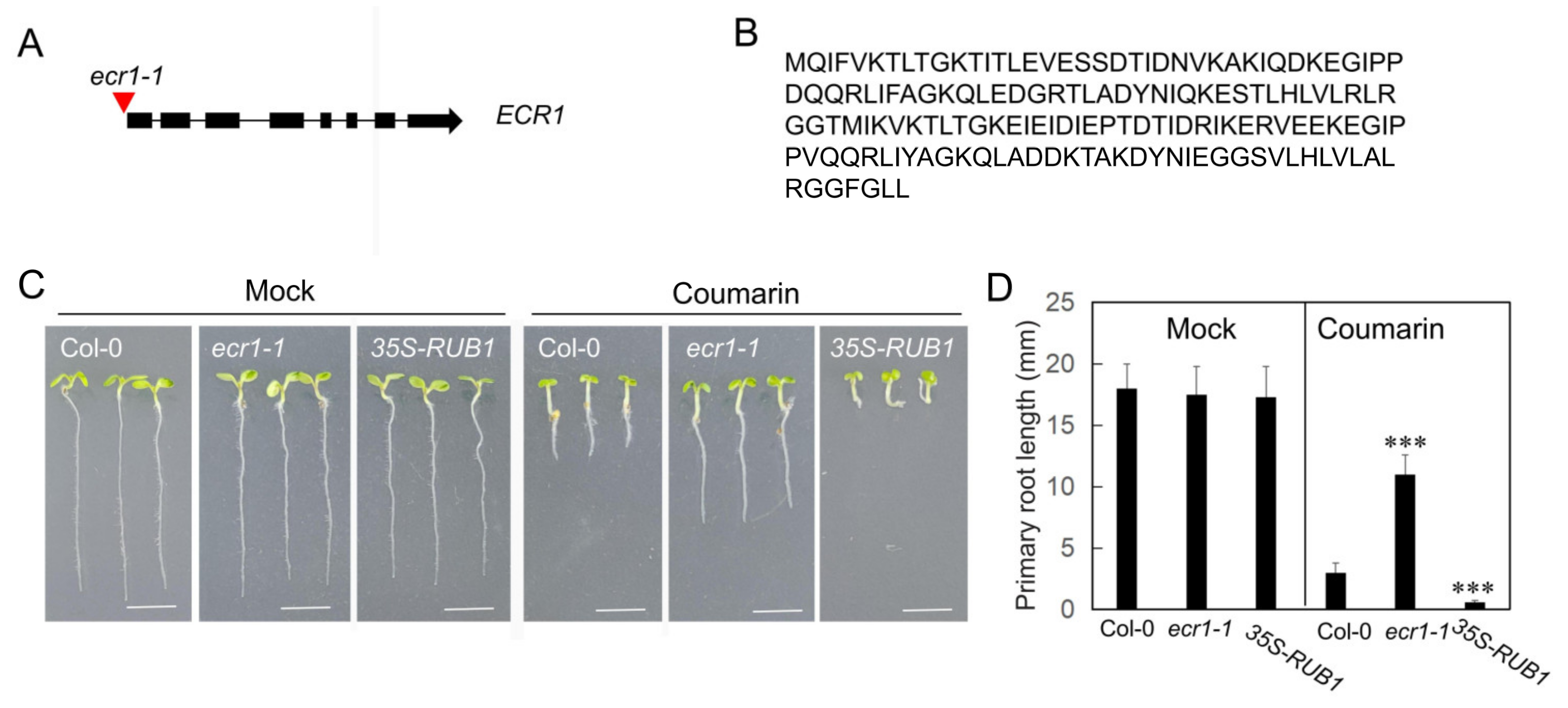

3.3. Coumarin Inhibition of Root Growth Requires NEDD8-Neddylation

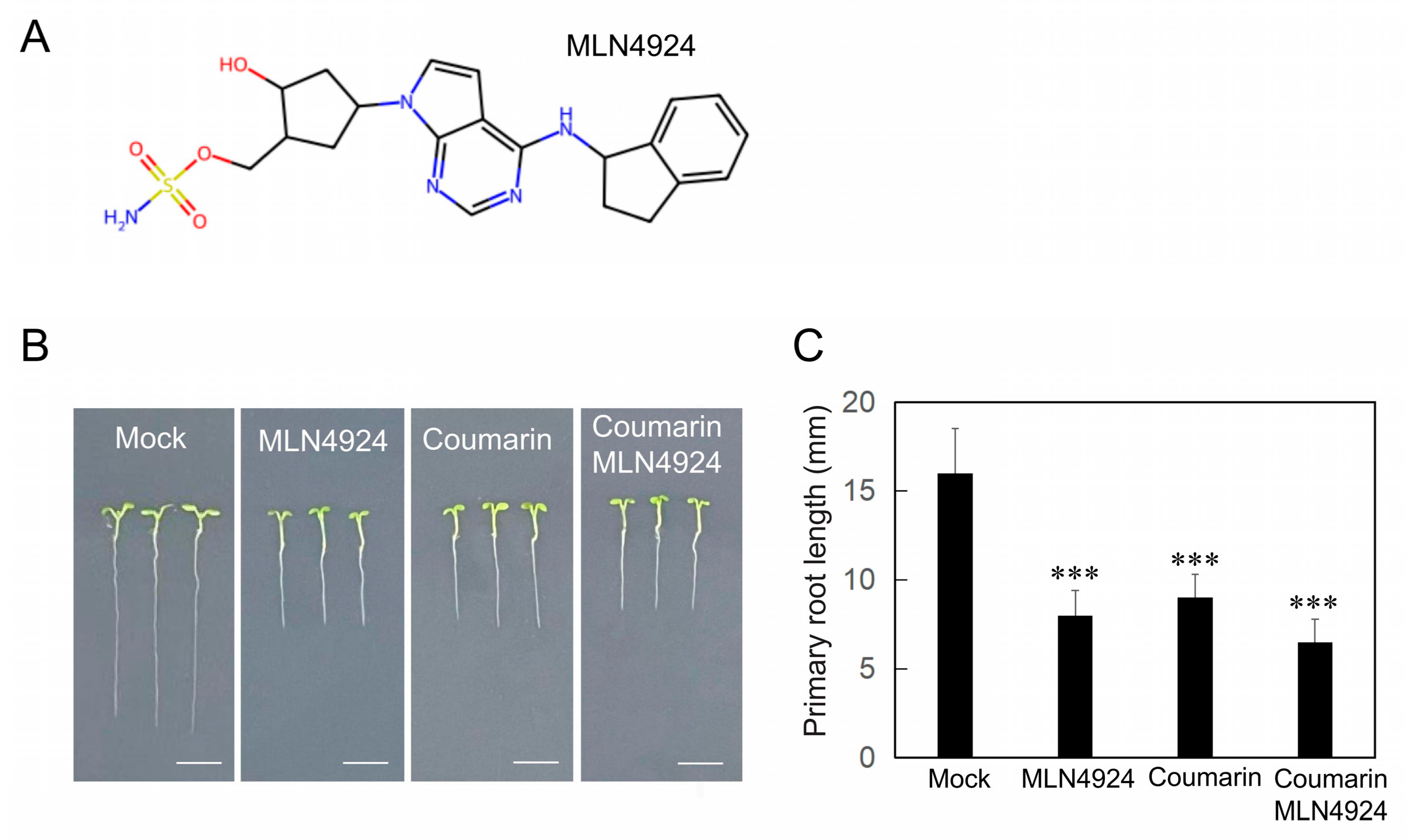

3.4. Convergent Inhibition of Root Growth by Coumarin and MLN4924

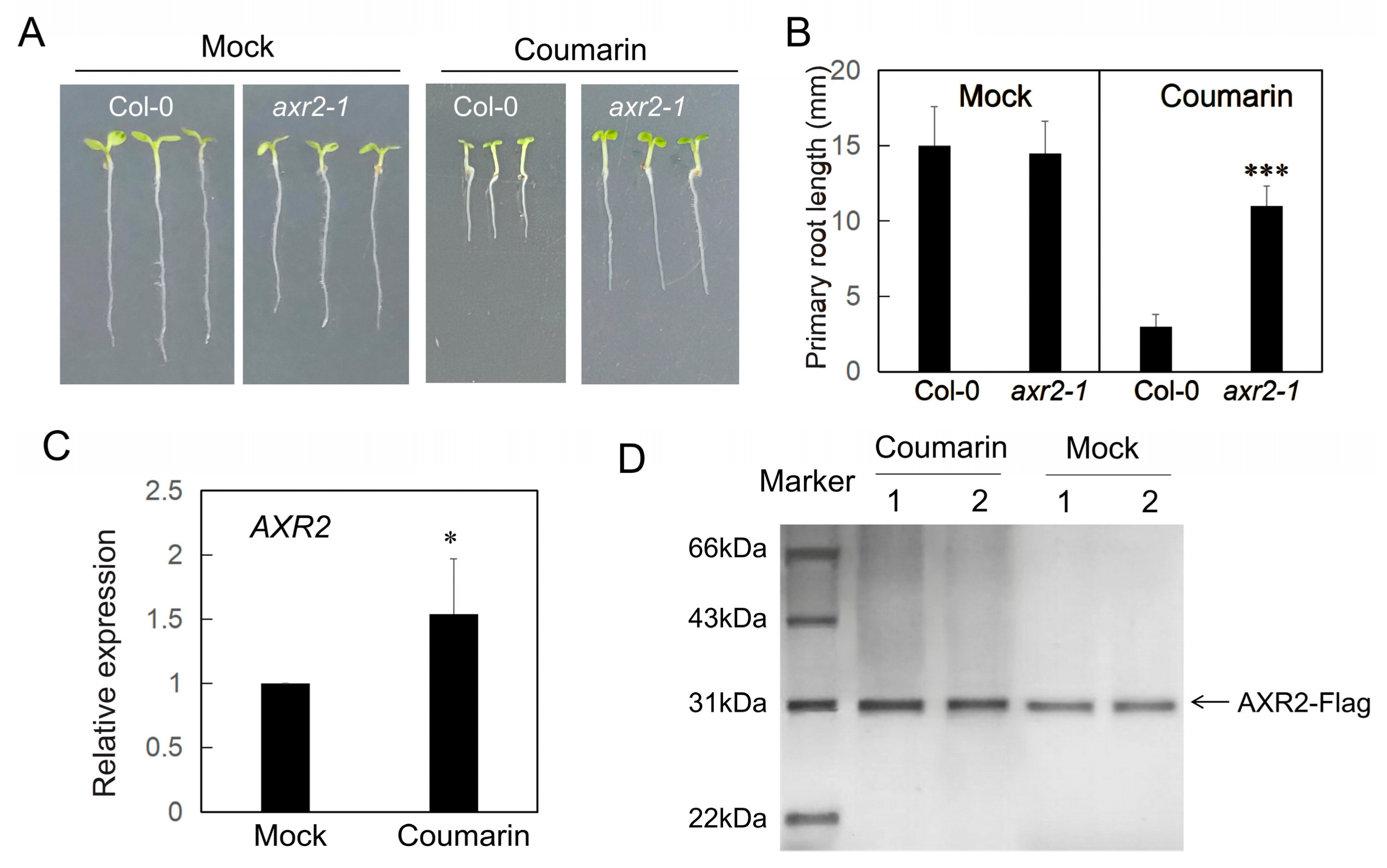

3.5. Coumarin Modulates the Degradation of AUX/IAA Protein

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AXR1 | AUXIN RESISTANT 1 |

| AXR2 | AUXIN RESISTANT 2 |

| ECR1 | E1 C-TERMINAL RELATED |

| NAE | NEDD8-activating enzyme |

| RUB1 | RELATED TO UBIQUITIN 1 |

| IAA7 | AUX/IAA 7 |

| NASC | Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre |

| MS | Murashige and Skoog |

| DAB | Diaminobenzidine |

| qPCR | Quantitative real-time PCR |

References

- Zobel, A.M.; Brown, S.A. Coumarins in the interactions between the plant and its environment. Allelopath. J. 1995, 2, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Abenavoli, M.R.; Cacco, G.; Sorgona, A.; Marabottini, R.; Paolacci, A.R.; Ciaffi, M.; Badiani, M. The inhibitory effects of coumarin on the germination of durum wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. durum, CV. Simeto) seeds. J. Chem. Ecol. 2006, 32, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.X.; Peng, Y.X.; Gao, J.D.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Q.J.; Fu, H.; Liu, J. Coumarin-Induced Delay of Rice Seed Germination Is Mediated by Suppression of Abscisic Acid Catabolism and Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voges, M.J.; Bai, Y.; Schulze-Lefert, P.; Sattely, E.S. Plant-derived coumarins shape the composition of an Arabidopsis synthetic root microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 12558–12565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupini, A.; Sorgona, A.; Princi, M.; Sunseri, F.; Abenavoli, M. Morphological and physiological effects of trans-cinnamic acid and its hydroxylated derivatives on maize root types. Plant Growth Regul. 2016, 78, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, J. An auxin-like action of coumarin. Science 1959, 129, 1675–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ma, A.; Li, J.; Du, Z.; Zhu, L.; Feng, G. Coumarin Promotes Hypocotyl Elongation by Increasing the Synthesis of Brassinosteroids in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlichting, C.D. The evolution of phenotypic plasticity in plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1986, 17, 667–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupini, A.; Araniti, F.; Mauceri, A.; Princi, M.P.; Sorgonà, A.; Sunseri, F.; Varanini, Z.; Abenavoli, M.R. Coumarin enhances nitrate uptake in maize roots through modulation of plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity. Plant Biol. 2018, 20, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robe, K.; Conejero, G.; Gao, F.; Lefebvre-Legendre, L.; Sylvestre-Gonon, E.; Rofidal, V.; Hem, S.; Rouhier, N.; Barberon, M.; Hecker, A.; et al. Coumarin accumulation and trafficking in Arabidopsis thaliana: A complex and dynamic process. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2062–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLoose, M.; Cho, H.; Bouain, N.; Choi, I.; Prom-U-Thai, C.; Shahzad, Z.; Zheng, L.; Rouached, H. PDR9 allelic variation and MYB63 modulate nutrient-dependent coumarin homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2024, 117, 1716–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Bucio, J.; Cruz-Ramirez, A.; Herrera-Estrella, L. The role of nutrient availability in regulating root architecture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2023, 6, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, A. Plastic plants and patchy soils. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, M.R.; De Santis, C.; Sidari, M.; Sorgonà, M.; Badiani, M.; Cacco, G. Influence of coumarin on the net nitrate uptake in durum wheat. New Phytol. 2001, 150, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, M.R.; Nicolò, A.; Lupini, A.; Oliva, S.; Sorgonà, A. Effects of different allelochemicals on root morphology of Arabidopsis thaliana. Allelopathy J. 2008, 22, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Lupini, A.; Sorgona, A.; Miller, A.J.; Abenavoli, M.R. Short-time effects of coumarin along the maize primary root axis. Plant Signal Behav. 2010, 5, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupini, A.; Araniti, F.; Sunseri, F.; Abenavoli, M.R. Coumarin interacts with auxin polar transport to modify root system architecture in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Growth Regul. 2014, 74, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakenjos, J.P.; Richter, R.; Dohmann, E.M.; Katsiarimpa, A.; Isono, E.; Schwechheimer, C. MLN4924 is an efficient inhibitor of NEDD8 conjugation in plants. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwechheimer, C. NEDD8-its role in the regulation of Cullin-RING ligases. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.H.; Taves, C. The effect of coumarin derivatives on the growth of Avena roots. Am. J. Bot. 1950, 37, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avers, C.J.; Goodwin, R.H. Studies on root. IV. Effects of coumarin and scopoletin on the standard root growth pater of Phleum pretense. Am. J. Bot. 1956, 43, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergo, E.M.; Abrahim, D.; Soares da Silva, P.C.; Kern, K.A.; Da Silva, L.J.; Voll, E.; IshiiIwamoto, E.L. Bidens pilosa L. exhibits high sensitivity to coumarin in comparison with three other weed species. J. Chem. Ecol. 2008, 34, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyser, H.M.; Lincoln, C.A.; Timpte, C.; Lammer, D.; Turner, J.; Estelle, M. Arabidopsis auxin-resistance gene AXR1 encodes a protein related to ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1. Nature 1993, 364, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammer, D.; Mathias, N.; Laplaza, J.M.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Callis, J.; Goebl, M.; Estelle, M. Modification of yeast Cdc53p by the ubiquitin-related protein rub1p affects function of the SCFCdc4 complex. Genes. Dev. 1998, 12, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pozo, J.C.; Estelle, M. The Arabidopsis cullin AtCUL1 is modified by the ubiquitin-related protein RUB1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 15342–15347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pozo, J.C.; Dharmasiri, S.; Hellmann, H.; Walker, L.; Gray, W.M.; Estelle, M. AXR1-ECR1-dependent conjugation of RUB1 to the Arabidopsis cullin AtCUL1 is required for auxin response. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmasiri, N.; Dharmasiri, S.; Weijers, D.; Karunarathna, N.; Jurgens, G.; Estelle, M. AXL and AXR1 have redundant functions in RUB conjugation and growth and development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007, 52, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostick, M.; Lochhead, S.R.; Honda, A.; Palmer, S.; Callis, J. Related to ubiquitin 1 and 2 are redundant and essential and regulate vegetative growth, auxin signaling, and ethylene production in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2418–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodward, A.W.; Ratzel, S.E.; Woodward, E.E.; Shamoo, Y.; Bartel, B. Mutation of E1-CONJUGATING ENZYME-RELATED1 decreases RELATED TO UBIQUITIN conjugation and alters auxin response and development. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; He, T.; Chang, H.; Du, Z.; Zhu, L.; Feng, G. Coumarin Inhibits Primary Root Growth by Modulating Auxin Signaling via Neddylation. Biology 2025, 14, 1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121701

Liu S, Li J, Zhao Z, He T, Chang H, Du Z, Zhu L, Feng G. Coumarin Inhibits Primary Root Growth by Modulating Auxin Signaling via Neddylation. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121701

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Siqi, Jie Li, Zixuan Zhao, Ting He, Hongxia Chang, Zhixuan Du, Longfei Zhu, and Guanping Feng. 2025. "Coumarin Inhibits Primary Root Growth by Modulating Auxin Signaling via Neddylation" Biology 14, no. 12: 1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121701

APA StyleLiu, S., Li, J., Zhao, Z., He, T., Chang, H., Du, Z., Zhu, L., & Feng, G. (2025). Coumarin Inhibits Primary Root Growth by Modulating Auxin Signaling via Neddylation. Biology, 14(12), 1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121701