A Multi-Breed GWAS for Carcass Weight in Jeju Black Cattle and Hanwoo × Jeju Black Crossbreds

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Population and Phenotypic Data

2.2. DNA Extraction and Genotyping

2.3. Quality Control of Genotype Data

2.4. Population Structure and Relatedness

2.5. GWAS Analysis

2.6. Identification of Candidate Genes

2.7. Functional Enrichment and Pathway Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Measurements

| Group | N | Age (Months, Mean ± SD) | Carcass Weight (kg, Mean ± SD) | Min (kg) | Max (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steers | 127 | 37.1 ± 4.68 | 405.3 ± 55.89 | 182 | 526 |

| Cows | 128 | 62.7 ± 37.24 | 326.1 ± 62.85 | 139 | 474 |

| Total | 255 | 50.0 ± 29.46 | 365.5 ± 71.38 | 139 | 526 |

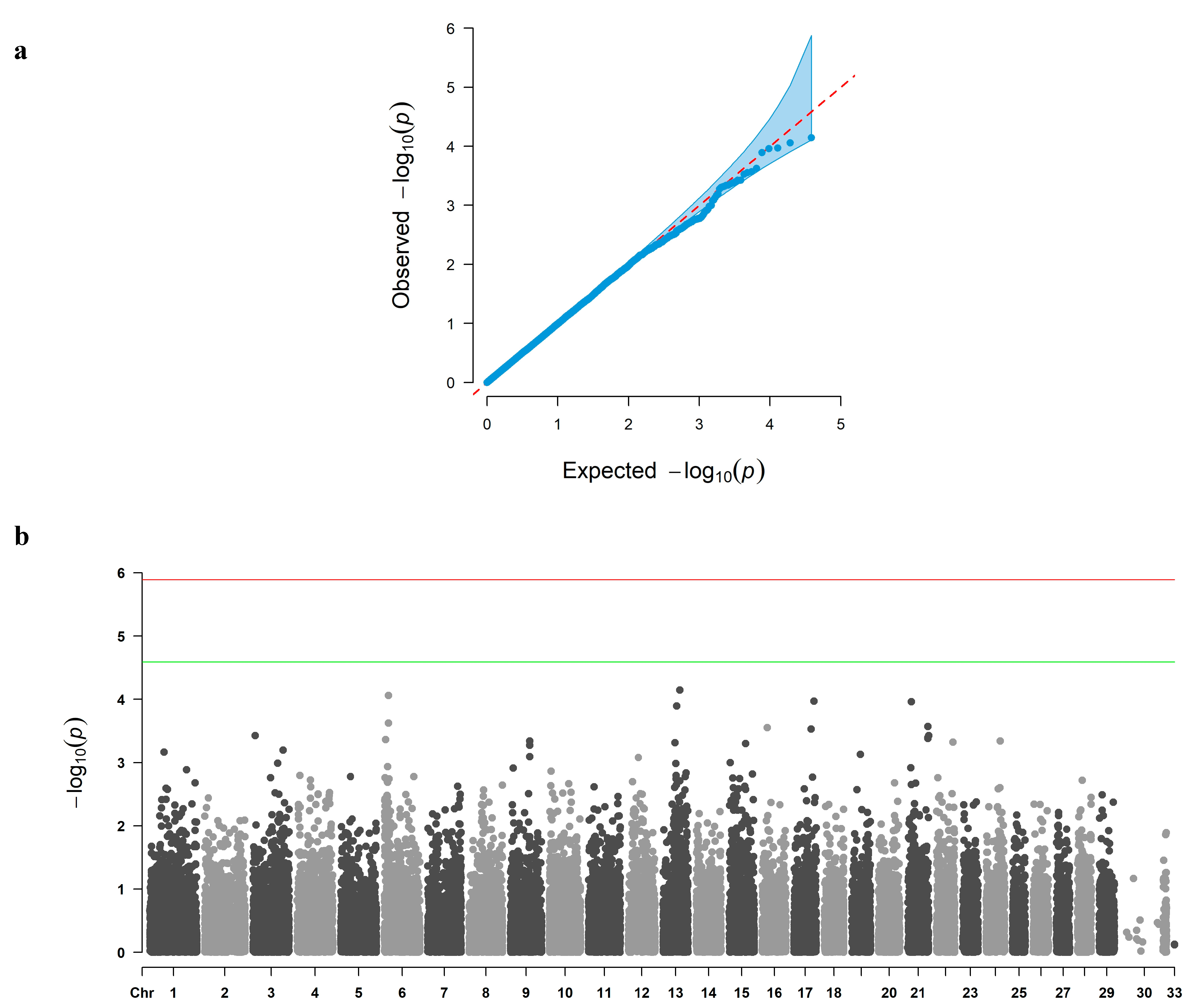

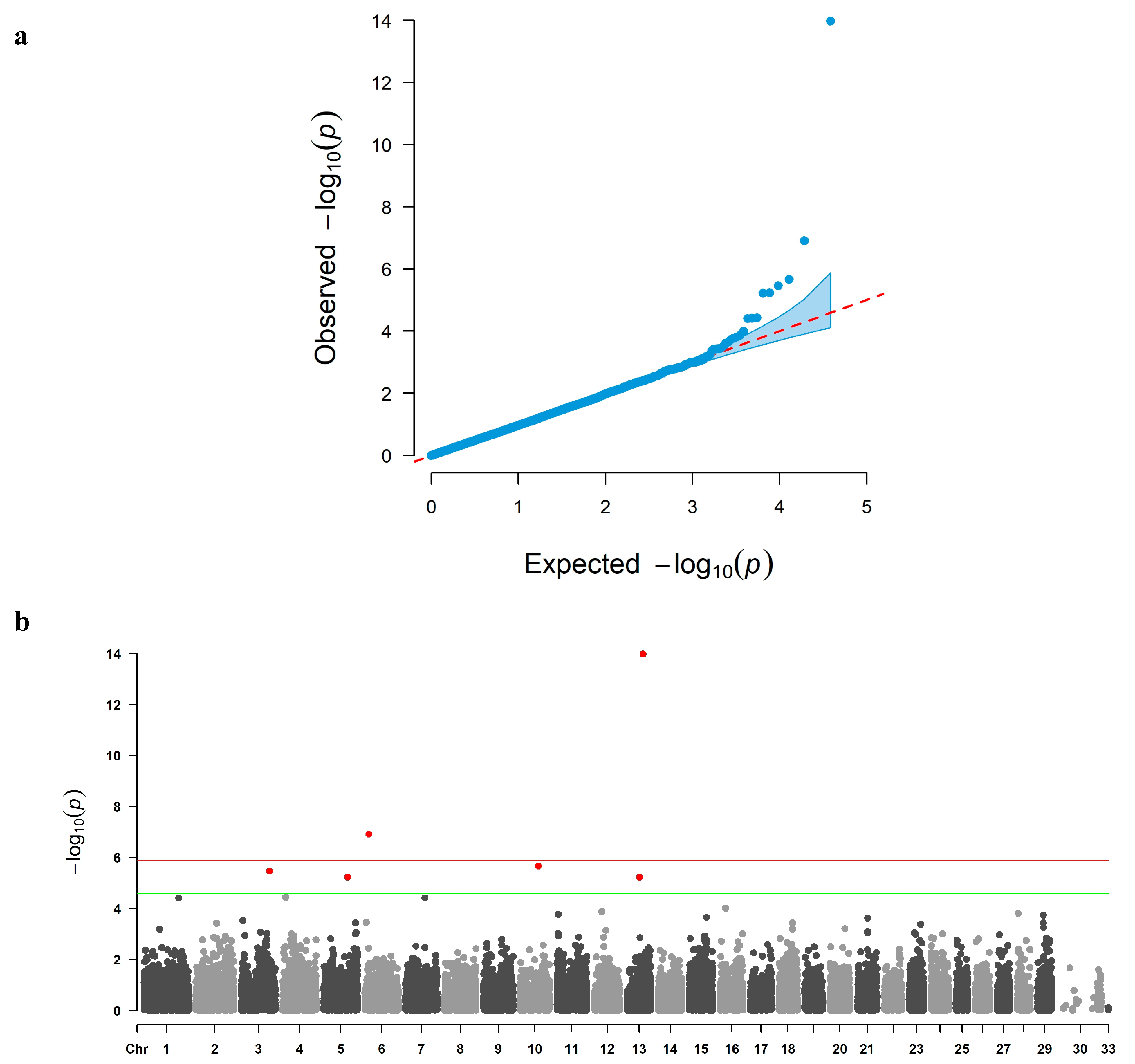

3.2. GWAS and Candidate Gene Identification

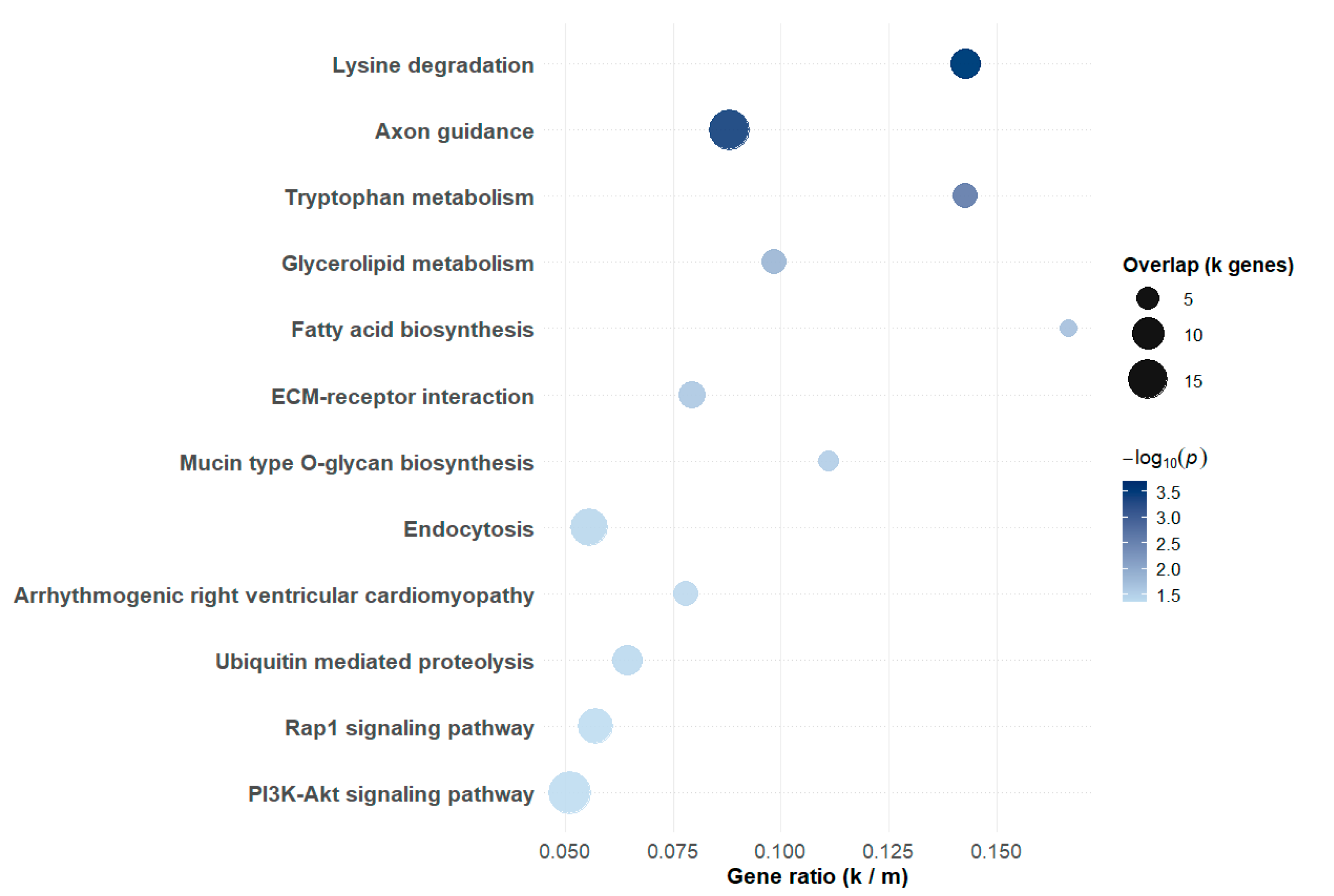

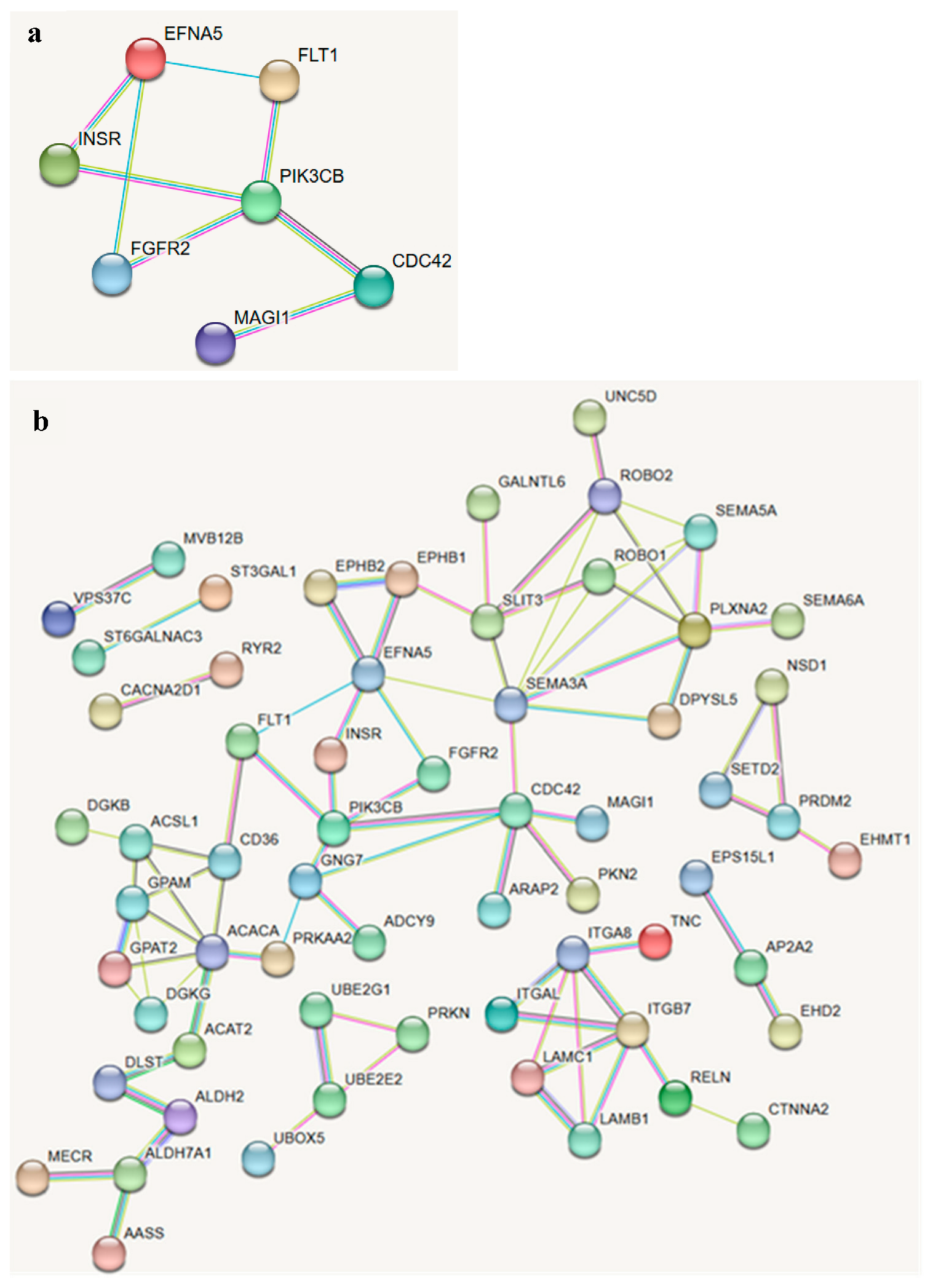

3.3. Functional Enrichment and Network Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kwon, K.-M.; Nogoy, K.M.C.; Jeon, H.-E.; Han, S.-J.; Woo, H.-C.; Heo, S.-M.; Hong, H.K.; Lee, J.-I.; Lee, D.H.; Choi, S.H. Market weight, slaughter age, and yield grade to determine economic carcass traits and primal cuts yield of Hanwoo beef. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2022, 64, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, Y.-H.; Choi, S.-B.; Jeon, G.-J.; Kim, H.-C.; Chung, H.-J.; Lee, J.-M.; Park, B.-Y.; Lee, S.-H. Prediction of retail beef yield using parameters based on Korean beef carcass grading standards. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2010, 30, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cho, S.; Park, B. Effects of calving season on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of Hanwoo steers. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. A—Anim. Sci. 2023, 72, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrban, H.; Naserkheil, M.; Lee, D.H.; Ibáñez-Escriche, N. Genetic parameters and correlations of related feed efficiency, growth, and carcass traits in Hanwoo beef cattle. Anim. Biosci. 2020, 34, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrban, H.; Lee, D.H.; Moradi, M.H.; IlCho, C.; Naserkheil, M.; Ibáñez-Escriche, N. Predictive performance of genomic selection methods for carcass traits in Hanwoo beef cattle: Impacts of the genetic architecture. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2017, 49, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Iqbal, A.; Alam, M.Z.; Lee, Y.-M.; Ha, J.-J.; Kim, J.-J. Estimation of genetic correlations and genomic prediction accuracy for reproductive and carcass traits in Hanwoo cows. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2024, 66, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Ko, K.; Kang, M.; Ryu, Y. Comparison of beef quality traits in Jeju black cattle, Hanwoo and Australian Wagyu. In Proceedings of the 58th International Congress of Meat Science and Technology-ICoMST 2012, Montreal, QC, Canada, 12–17 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M.A.; Jang, E.-B.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.-M.; Kim, J.-J. Genomic prediction of genotyped and non-genotyped Jeju black cattle using single-and multi-trait methods for carcass traits. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 23, 1854–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Oh, W.; Lee, S.; Khan, M.; Ko, M.; Kim, H.; Ha, J.K. Growth performance and carcass evaluation of Jeju native cattle and its crossbreds fed for long fattening period. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 20, 1909–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Kim, C.-N.; Ko, K.-B.; Park, S.-P.; Kim, H.-K.; Kim, J.-M.; Ryu, Y.-C. Comparisons of beef fatty acid and amino acid characteristics between Jeju black cattle, Hanwoo, and Wagyu breeds. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2019, 39, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, V.-B.; Kim, D.-G.; Song, D.-H.; Ko, J.-H.; Kim, H.-W.; Bae, I.-S.; Kim, Y.-S.; Cho, S.-H. Quality properties and flavor-related components of beef longissimus lumborum muscle from four Korean native cattle breeds. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2024, 44, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Haque, M.A.; Iqbal, A.; Lee, Y.-M.; Ha, J.-J.; Jin, S.; Park, B.; Kim, N.-Y.; Won, J.I.; Kim, J.-J. Genome-wide association study to identify QTL for carcass traits in Korean Hanwoo cattle. Animals 2023, 13, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.D.; Lee, G.H.; Kong, H.S. Estimation of heritability and genetic parameters for carcass traits and primal cut production traits in Hanwoo. J. Anim. Reprod. Biotechnol. 2024, 39, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.M.; Majeres, L.E.; Dilger, A.C.; McCann, J.C.; Cassady, C.J.; Shike, D.W.; Beever, J.E. Characterizing differences in the muscle transcriptome between cattle with alternative LCORL-NCAPG haplotypes. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeres, L.E.; Dilger, A.C.; Shike, D.W.; McCann, J.C.; Beever, J.E. Defining a haplotype encompassing the LCORL-NCAPG locus associated with increased lean growth in beef cattle. Genes 2024, 15, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardicli, S.; Dincel, D.; Samli, H.; Balci, F. Effects of polymorphisms at LEP, CAST, CAPN1, GHR, FABP4 and DGAT1 genes on fattening performance and carcass traits in Simmental bulls. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2017, 60, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravčíková, N.; Kasarda, R.; Vostrý, L.; Krupová, Z.; Krupa, E.; Lehocká, K.; Olšanská, B.; Trakovická, A.; Nádaský, R.; Židek, R. Analysis of selection signatures in the beef cattle genome. Czech J. Anim. Sci 2019, 64, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, J.-M. Genome-Wide Association Studies: A Powerful Approach for Identifying Genomic Variants for Livestock Breeding and Disease Management. In Bioinformatics in Veterinary Science: Vetinformatics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 87–117. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Huang, M.; Fan, B.; Buckler, E.S.; Zhang, Z. Iterative usage of fixed and random effect models for powerful and efficient genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmec, A.; Schnable, P.S. Farm CPU pp: Efficient large-scale genomewide association studies. Plant Direct 2018, 2, e00053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, M.; Kantar, M.B.; Longman, R.J.; Lee, C.; Oshiro, M.; Caires, K.; He, Y. Genome-wide association study for carcass weight in pasture-finished beef cattle in Hawai’i. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1168150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naserkheil, M.; Mehrban, H.; Lee, D.; Park, M.N. Genome-wide association study for carcass primal cut yields using single-step Bayesian approach in Hanwoo cattle. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 752424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, K.; Lee, S.-H.; Chung, K.-Y.; Park, J.-E.; Jang, G.-W.; Park, M.-R.; Kim, N.Y.; Kim, T.-H.; Chai, H.-H.; Park, W.C. A gene-set enrichment and protein–protein interaction network-based GWAS with regulatory SNPs identifies candidate genes and pathways associated with carcass traits in hanwoo cattle. Genes 2020, 11, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrollahi, B.; Lee, H.-J.; Baek, Y.C.; Jin, S.; Jang, G.-S.; Moon, S.J.; Um, K.-H.; Jang, S.S.; Park, M.S. Transcriptomic analysis of Newborn Hanwoo calves: Effects of maternal overnutrition during mid-to late pregnancy on Subcutaneous Adipose tissue and liver. Genes 2024, 15, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Lee, Y.-M.; Son, H.-J.; Hanna, L.H.; Riley, D.G.; Mannen, H.; Sasazaki, S.; Park, S.P.; Kim, J.-J. Genetic characteristics of Korean Jeju Black cattle with high density single nucleotide polymorphisms. Anim. Biosci. 2020, 34, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, M.A.; Iqbal, A.; Bae, H.; Lee, S.E.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.M.; Kim, J.J. Assessment of genomic breeding values and their accuracies for carcass traits in Jeju Black cattle using whole-genome SNP chip panels. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2023, 140, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.A.; Dykes, D.D.; Polesky, H. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; De Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.; Bickhart, D.; Schnabel, R.; Koren, S.; Elsik, C.; Zimin, A.; Dreischer, C.; Schultheiss, S.; Hall, R.; Schroeder, S. Modernizing the bovine reference genome assembly. In Proceedings of the 11th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy, Auckland, New Zealand, 11–16 February 2018; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zweifach, A. Bonferroni’s method, not Tukey’s, should be used to control the total number of false positives when making multiple pairwise comparisons in experiments with few replicates. SLAS Discov. 2025, 35, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durinck, S.; Spellman, P.T.; Birney, E.; Huber, W. Mapping identifiers for the integration of genomic datasets with the R/Bioconductor package biomaRt. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durinck, S.; Moreau, Y.; Kasprzyk, A.; Davis, S.; De Moor, B.; Brazma, A.; Huber, W. BioMart and Bioconductor: A powerful link between biological databases and microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3439–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov, M.V.; Jones, M.R.; Rouillard, A.D.; Fernandez, N.F.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Koplev, S.; Jenkins, S.L.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Lachmann, A. Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W90–W97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P. The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W.; Lee, W.-S.; Lee, S.; Khan, M.; Ko, M.; Yang, S.; Kim, H.; Ha, J.K. Feed consumption, body weight gain and carcass characteristics of Jeju Native Cattle and its crossbreds fed for short fattening period. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 21, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Lee, S.S.; Cho, K.H.; Cho, C.; Choy, Y.H.; Choi, J.G.; Park, B.; Na, C.S.; Choi, T. Correlation analyses on body size traits, carcass traits and primal cuts in Hanwoo steers. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2013, 55, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Van Eenennaam, A.L.; Weigel, K.A.; Young, A.E.; Cleveland, M.A.; Dekkers, J.C. Applied animal genomics: Results from the field. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2014, 2, 105–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolormaa, S.; Pryce, J.E.; Reverter, A.; Zhang, Y.; Barendse, W.; Kemper, K.; Tier, B.; Savin, K.; Hayes, B.J.; Goddard, M.E. A multi-trait, meta-analysis for detecting pleiotropic polymorphisms for stature, fatness and reproduction in beef cattle. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baneh, H.; Elatkin, N.; Gentzbittel, L. Genome-wide association studies and genetic architecture of carcass traits in Angus beef cattle using imputed whole-genome sequences data. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2025, 57, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikawa, L.M.; Mota, L.F.M.; Schmidt, P.I.; Frezarim, G.B.; Fonseca, L.F.S.; Magalhães, A.F.B.; Silva, D.A.; Carvalheiro, R.; Chardulo, L.A.L.; de Albuquerque, L.G. Genome-wide scans identify biological and metabolic pathways regulating carcass and meat quality traits in beef cattle. Meat Sci. 2024, 209, 109402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.S.; Lim, D.; Park, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.; Gondro, C.; Park, B.; Lee, S. Functional partitioning of genomic variance and genome-wide association study for carcass traits in Korean Hanwoo cattle using imputed sequence level SNP data. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasuga, A. PLAG1 and NCAPG-LCORL in livestock. Anim. Sci. J. 2016, 87, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Lee, Y.-M.; Ha, J.-J.; Jin, S.; Park, B.; Kim, N.-Y.; Won, J.-I.; Kim, J.-J. Genome-wide association study identifies genomic regions associated with key reproductive traits in Korean Hanwoo cows. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, P.; Li, P.; Mandel, J.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, J.M.; Behringer, R.R.; De Crombrugghe, B.; Lefebvre, V. The transcription factors L-Sox5 and Sox6 are essential for cartilage formation. Dev. Cell 2001, 1, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.-F.; Lefebvre, V. The transcription factors SOX9 and SOX5/SOX6 cooperate genome-wide through super-enhancers to drive chondrogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 8183–8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chu, M.; Bao, Q.; Bao, P.; Guo, X.; Liang, C.; Yan, P. Two different copy number variations of the SOX5 and SOX8 genes in yak and their association with growth traits. Animals 2022, 12, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.M.; Kim, J.I.; Song, C.E.; Shin, J.Y.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Cho, B.-D.; Kim, B.-W.; Lee, J.-G. A study on genetic parameters of carcass weight and body type measurements in Hanwoo Steer. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2008, 50, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Iqbal, A.; Yu, H.; Jiang, P.; Zhao, Z. Deciphering the key regulatory roles of KLF6 and bta-miR-148a on milk fat metabolism in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Genes 2022, 13, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, S.H.A.; Khan, R.; Schreurs, N.M.; Guo, H.; Gui, L.-s.; Mei, C.; Zan, L. Expression of the bovine KLF6 gene polymorphisms and their association with carcass and body measures in Qinchuan cattle (Bos taurus). Genomics 2020, 112, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas Raza, S.H.; Zhong, R.; Wei, X.; Zhao, G.; Zan, L.; Pant, S.D.; Schreurs, N.M.; Lei, H. Investigating the role of KLF6 in the growth of bovine preadipocytes: Using transcriptomic analyses to understand beef quality. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 9656–9668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.D.; Pavitt, G.D. A new function and complexity for protein translation initiation factor eIF2B. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 2660–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Xu, J.; Tian, Y.; Liao, B.; Lang, J.; Lin, H.; Mo, X.; Lu, Q.; Tian, G.; Bing, P. Gene coexpression network and module analysis across 52 human tissues. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 6782046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fang, W.; Xiao, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, Y. Effect of IGF1 on Myogenic Proliferation and Differentiation of Bovine Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells Through PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway. Genes 2024, 15, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Miao, M.; Tan, H.; Hu, D.; Li, X.; Ding, X.; Li, G. Proteomic studies on the mechanism of myostatin regulating cattle skeletal muscle development. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 752129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ding, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, C.; Su, Z.; Xu, J.; Qu, C.; Shi, Y.; Kang, X. FHL3 gene regulates bovine skeletal muscle cell growth through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2024, 52, 101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerman, M.A.; Glass, D.J. Signaling pathways controlling skeletal muscle mass. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 49, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Dai, R.; Ma, X.; Huang, C.; Ma, X.; Li, X.; La, Y.; Dingkao, R.; Renqing, J.; Guo, X. Proteomic analysis reveals the effects of different dietary protein levels on growth and development of Jersey-Yak. Animals 2024, 14, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, F.M.; Mohammadabadi, M.; Roudbari, Z.; Gorji, A.E.; Sadkowski, T. Network visualization of genes involved in skeletal muscle myogenesis in livestock animals. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, K.E.; Chen, Y.; McDonald, J.A.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, R. Rap1 coordinates cell-cell adhesion and cytoskeletal reorganization to drive collective cell migration in vivo. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 2587–2601.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T. Role of extracellular matrix in development of skeletal muscle and postmortem aging of meat. Meat Sci. 2015, 109, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, K.J. Triennial growth symposium: The nutrition of muscle growth: Impacts of nutrition on the proliferation and differentiation of satellite cells in livestock species. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 2258–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Mukiibi, R.; Wang, Y.; Plastow, G.S.; Li, C. Identification of candidate genes and enriched biological functions for feed efficiency traits by integrating plasma metabolites and imputed whole genome sequence variants in beef cattle. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantalapiedra-Hijar, G.; Nedelkov, K.; Crosson, P.; McGee, M. Some plasma biomarkers of residual feed intake in beef cattle remain consistent regardless of intake level. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Ji, S.-Y.; Baek, Y.-C.; Lee, S.; Oh, Y.K.; Reddy, K.E.; Seo, H.-W.; Cho, S.; Lee, H.-J. Metabolomics analysis of the beef samples with different meat qualities and tastes. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2020, 40, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.; Alkhoder, H.; Choi, T.-J.; Liu, Z.; Reents, R. Genomic evaluation of carcass traits of Korean beef cattle Hanwoo using a single-step marker effect model. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naserkheil, M.; Mehrban, H.; Lee, D.; Park, M.N. Evaluation of genome-enabled prediction for carcass primal cut yields using single-step genomic best linear unbiased prediction in Hanwoo cattle. Genes 2021, 12, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, S.; Watanabe, T.; Mizoshita, K.; Tatsuda, K.; Fujita, T.; Watanabe, N.; Sugimoto, Y.; Takasuga, A. Genome-wide association study identified three major QTL for carcass weight including the PLAG1-CHCHD7 QTN for stature in Japanese Black cattle. BMC Genet. 2012, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Choi, B.H.; Lim, D.; Gondro, C.; Cho, Y.M.; Dang, C.G.; Sharma, A.; Jang, G.W.; Lee, K.T.; Yoon, D. Genome-wide association study identifies major loci for carcass weight on BTA14 in Hanwoo (Korean cattle). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edea, Z.; Jeoung, Y.H.; Shin, S.-S.; Ku, J.; Seo, S.; Kim, I.-H.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, K.-S. Genome–wide association study of carcass weight in commercial Hanwoo cattle. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 31, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibtisham, F.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, M.; An, L.; Ramzan, M.B.; Nawab, A.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Xu, Y. Genomic selection and its application in animal breeding. Thai J. Vet. Med. 2017, 47, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Vignato, B.; Cesar, A.S.M.; Afonso, J.; Moreira, G.C.M.; Poleti, M.D.; Petrini, J.; Garcia, I.S.; Clemente, L.G.; Mourão, G.B.; Regitano, L.C.d.A. Integrative analysis between genome-wide association study and expression quantitative trait loci reveals bovine muscle gene expression regulatory polymorphisms associated with intramuscular fat and backfat thickness. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 935238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| QC Stage | Number of SNPs |

|---|---|

| Before QC (GenomeStudio FinalReport) | 53,866 |

| After QC (final GWAS dataset) | 39,055 |

| CHR | SNP ID | POS | REF | ALT | Effect | SE | p-Value | %Var | Positional Candidate Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | ARS-BFGL-NGS-21065 | 56,698,060 | G | A | 25.0962 | 3.317 | 1.06 × 10−14 | 9.58 | PHACTR3 |

| 6 | ARS-BFGL-NGS-116085 | 14,038,382 | A | C | 10.3934 | 3.827 | 1.22 × 10−07 | 4.54 | ENSBTAG00000064813 |

| 10 | ARS-BFGL-BAC-14182 | 64,224,480 | A | C | –18.8834 | 4.246 | 2.17 × 10−06 | 4.02 | ENSBTAG00000064392 |

| 3 | Hapmap51970-BTA-100380 | 101,076,596 | A | G | 22.4000 | 5.918 | 3.46 × 10−06 | 2.55 | EIF2B3, HECTD3 |

| 5 | BTA-74501-no-rs | 86,142,655 | G | A | –13.0463 | 3.537 | 5.81 × 10−06 | 2.86 | SOX5 |

| 13 | ARS-BFGL-NGS-23974 | 44,467,210 | C | A | 14.4027 | 3.613 | 6.05 × 10−06 | 3.30 | KLF6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Won, M.; Lee, J.; Shin, S.-M.; Lee, S.-E.; Kim, W.-J.; Kim, E.-T.; Kim, T.-H.; Park, H.-B.; Shokrollahi, B. A Multi-Breed GWAS for Carcass Weight in Jeju Black Cattle and Hanwoo × Jeju Black Crossbreds. Biology 2025, 14, 1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121699

Won M, Lee J, Shin S-M, Lee S-E, Kim W-J, Kim E-T, Kim T-H, Park H-B, Shokrollahi B. A Multi-Breed GWAS for Carcass Weight in Jeju Black Cattle and Hanwoo × Jeju Black Crossbreds. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121699

Chicago/Turabian StyleWon, Miyoung, Jongan Lee, Sang-Min Shin, Seung-Eun Lee, Won-Jae Kim, Eun-Tae Kim, Tae-Hee Kim, Hee-Bok Park, and Borhan Shokrollahi. 2025. "A Multi-Breed GWAS for Carcass Weight in Jeju Black Cattle and Hanwoo × Jeju Black Crossbreds" Biology 14, no. 12: 1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121699

APA StyleWon, M., Lee, J., Shin, S.-M., Lee, S.-E., Kim, W.-J., Kim, E.-T., Kim, T.-H., Park, H.-B., & Shokrollahi, B. (2025). A Multi-Breed GWAS for Carcass Weight in Jeju Black Cattle and Hanwoo × Jeju Black Crossbreds. Biology, 14(12), 1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121699