Histone Deacetylase BpHST1 Regulates Plant Architecture and Photosynthesis in Birch

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Cultivation

2.2. Identification and Analysis of BpHST1 Gene in Birch

2.3. Total RNA Extraction

2.4. qRT-PCR

2.5. Plasmid Construction and Plant Transformation

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscope

2.7. Photosynthetic Gas Exchange Measurements

2.8. RNA-Seq

2.9. ChIP-Seq

3. Results

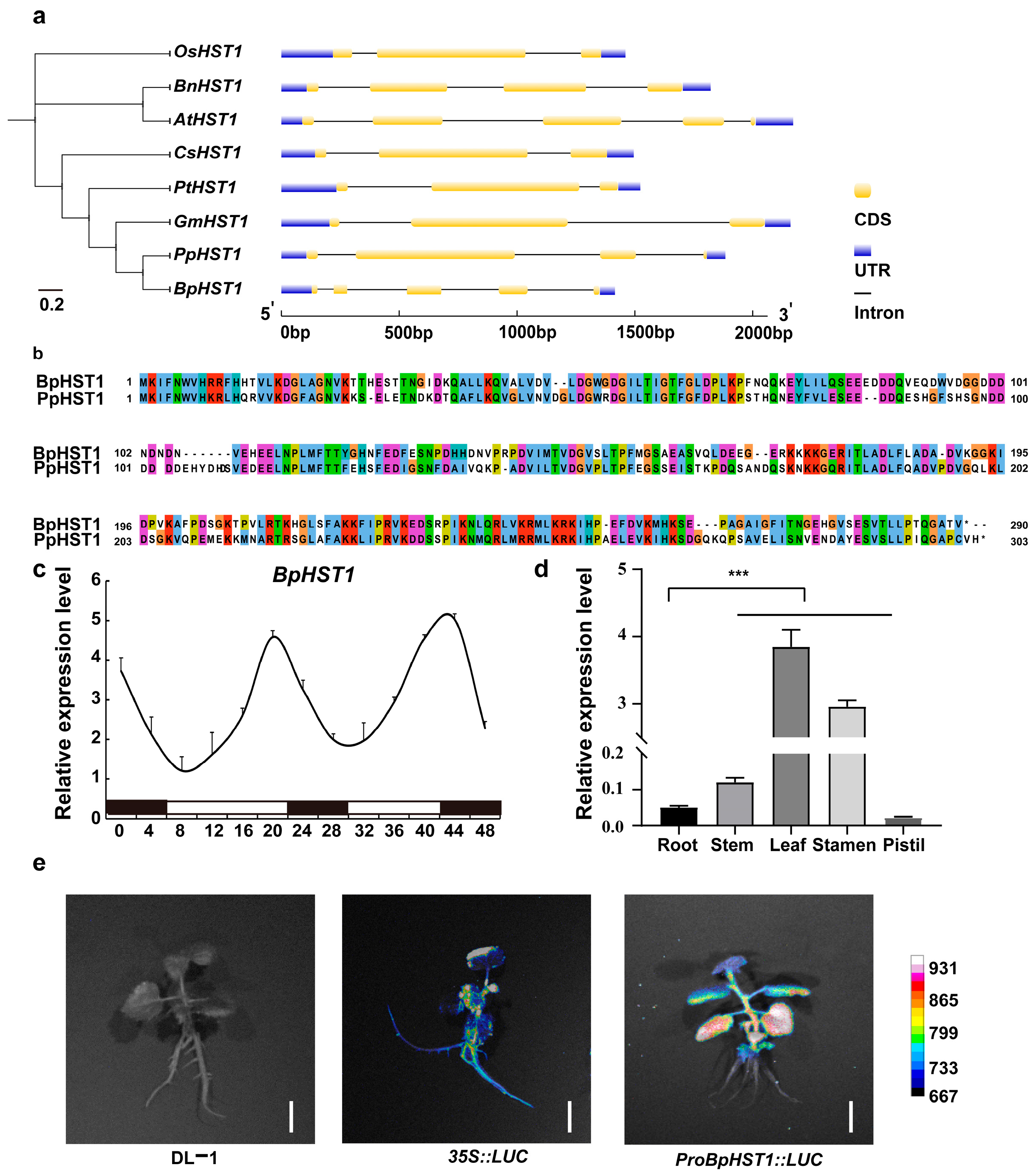

3.1. Identified and Expressed of BpHST1 in Birch

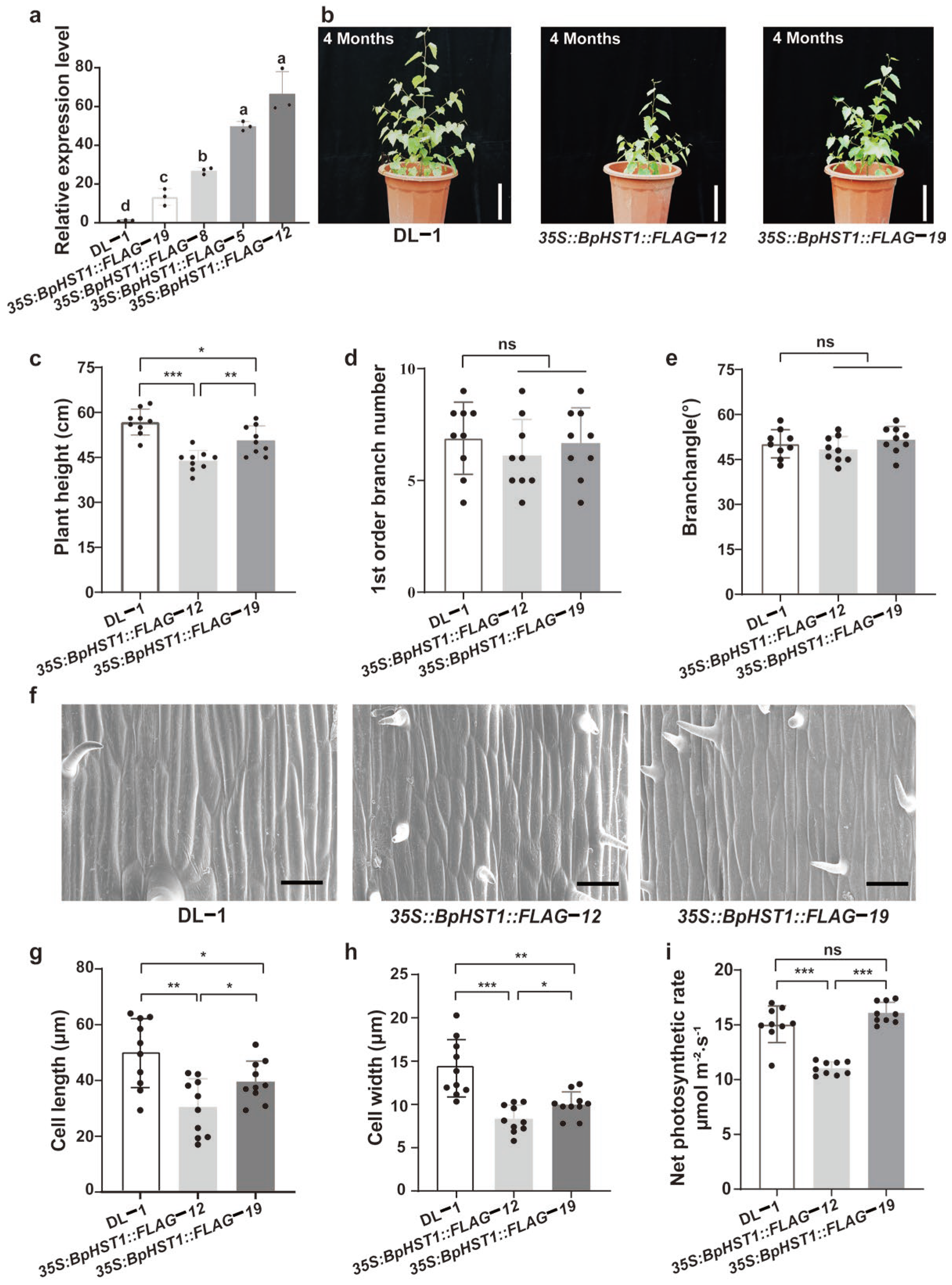

3.2. Overexpression of BpHST1 Inhibited the Growth and Development in Birch

3.3. Overexpression of BpHST1 Compromised Light Harvesting Capacity

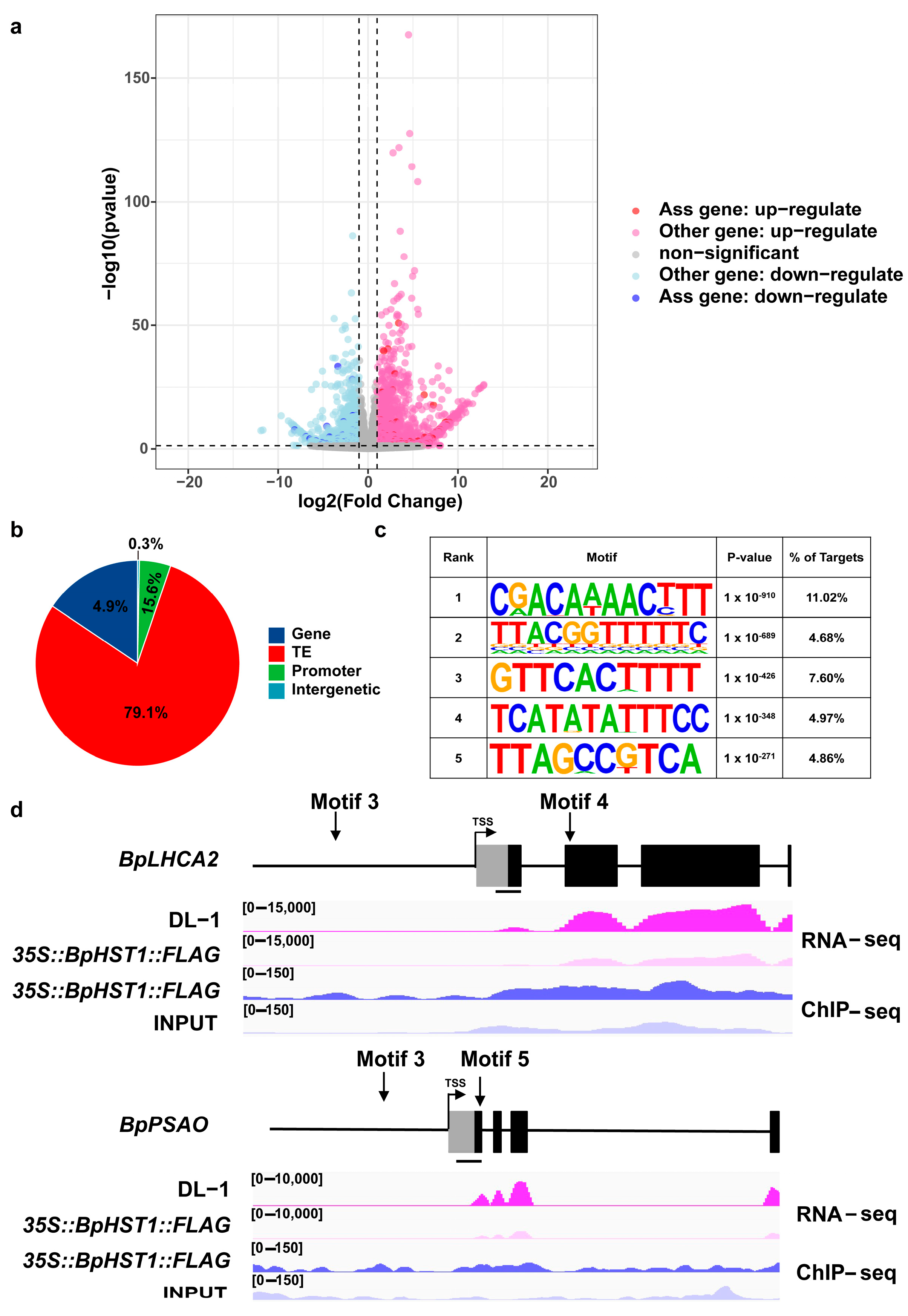

3.4. BpHST1 Binds to the Promoter of BpLHCA2 and Represses the Expression of Its Downstream Genes

4. Discussion

4.1. BpHST1 Acted as a Downstream Effector of Light Signaling in Birch

4.2. BpHST1 Mediated Repression of Light-Harvesting Gene BpLHCA2

4.3. The Recruitment Mechanism of BpHST1

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, S.; Chen, Z.J. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance during plant evolution and breeding. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 1203–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, G. Dynamic epigenetic modifications in plant sugar signal transduction. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Cao, X.; Chen, X.; Deng, X.; Deng, X.W.; Ding, Y.; Dong, A.; Duan, C.-G.; Fang, X.; Gong, L. Epigenetics in the modern era of crop improvements. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 1570–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwee, J.; Tian, W.; Qian, S.; Zhong, X. DNA methylation dynamics: Patterns, regulation, and function. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2025, 88, 102787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, R.; Ginder, G.D. DNA methylation. J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 1999, 93, 4059–4070. [Google Scholar]

- Bastié, N.; Chapard, C.; Dauban, L.; Gadal, O.; Beckouët, F.; Koszul, R. Smc3 acetylation, Pds5 and Scc2 control the translocase activity that establishes cohesin-dependent chromatin loops. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2022, 6, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-T.; Luo, M.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Wu, K. Involvement of Arabidopsis histone deacetylase HDA6 in ABA and salt stress response. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 3345–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.-R.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.-L.; Li, L.-C.; Chen, W.-Q.; Xu, Z.-H.; Bai, S.-N. Histone acetylation affects expression of cellular patterning genes in the Arabidopsis root epidermis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 14469–14474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murfett, J.; Wang, X.-J.; Hagen, G.; Guilfoyle, T.J. Identification of Arabidopsis histone deacetylase HDA6 mutants that affect transgene expression. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 1047–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Tian, Y.; Hao, S.; Jin, X.; He, Z.; An, L.; Song, Y. The AtHDA6-AtSK2 module promotes cold tolerance by enhancing shikimate metabolism and antioxidant activity. Plant J. 2025, 122, e70197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, L.-C.; Chen, W.-Q.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z.-H.; Bai, S.-N. HDA18 affects cell fate in Arabidopsis root epidermis via histone acetylation at four kinase genes. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilak, P.; Kotnik, F.; Née, G.; Seidel, J.; Sindlinger, J.; Heinkow, P.; Eirich, J.; Schwarzer, D.; Finkemeier, I. Proteome-wide lysine acetylation profiling to investigate the involvement of histone deacetylase HDA5 in the salt stress response of Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J. 2023, 115, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohe, A.R.; Chaudhury, A. Genetic and epigenetic processes in seed development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bu, F.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Xue, W.; Guo, R.; Qi, J.; Kim, C. Enhancing nature’s palette through the epigenetic breeding of flower color in chrysanthemum. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 2117–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Gallusci, P.; Lang, Z. Fruit development and epigenetic modifications. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Chang, C. Insight into the role of epigenetic processes in abiotic and biotic stress response in wheat and barley. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.N.; Zhu, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.K.; Duan, C.G. Epigenetic regulation in plant abiotic stress responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 5, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, X.; Liu, S.; Ke, S.; Dai, H.; Xie, X.M.; Hsieh, T.F.; Zhang, X.Q. Epigenetic modification of ESP, encoding a putative long noncoding RNA, affects panicle architecture in rice. Rice 2019, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Xu, M.; Guan, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, S.; Qu, H.; Chu, J.; Xu, Y. Sugar transporter modulates nitrogen-determined tillering and yield formation in rice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Able, A.J.; Able, J.A. SMARTER de-stressed cereal breeding. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 909–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooke, R.; Johannes, F.; Wardenaar, R.; Becker, F.; Etcheverry, M.; Colot, V.; Vreugdenhil, D.; Keurentjes, J.J. Epigenetic basis of morphological variation and phenotypic plasticity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeley, K.J.; Zuleta, D. Changing forests under climate change. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 984–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B. Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 2008, 320, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräutigam, K.; Vining, K.J.; Lafon-Placette, C.; Fossdal, C.G.; Mirouze, M.; Marcos, J.G.; Fluch, S.; Fraga, M.F.; Guevara, M.Á.; Abarca, D. Epigenetic regulation of adaptive responses of forest tree species to the environment. Ecol. Evol. 2013, 3, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicotra, A.B.; Atkin, O.K.; Bonser, S.P.; Davidson, A.M.; Finnegan, E.J.; Mathesius, U.; Poot, P.; Purugganan, M.D.; Richards, C.L.; Valladares, F. Plant phenotypic plasticity in a changing climate. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xie, C.; Cheng, L.; Tong, H.; Bock, R.; Qian, Q.; Zhou, W. The next Green Revolution: Integrating crop architectype and physiotype. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 10, 2479–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, A.; Ashikari, M.; Ueguchi-Tanaka, M.; Itoh, H.; Nishimura, A.; Swapan, D.; Ishiyama, K.; Saito, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Khush, G. Green revolution: A mutant gibberellin-synthesis gene in rice. Nature 2002, 416, 701–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, K.; Harberd, N.P.; Fu, X. Green Revolution DELLAs: From translational reinitiation to future sustainable agriculture. Mol. Plant. 2021, 14, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhong, S.; Li, Y.; Zhu, C.; Liu, J.; Lin, Z. The tin1 gene retains the function of promoting tillering in maize. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Huang, S.; Lu, Q.; Li, S.; Zhao, S.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, L. UV-B irradiation-activated E3 ligase GmILPA1 modulates gibberellin catabolism to increase plant height in soybean. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.L., Jr.; Hollender, C. Branching out: New insights into the genetic regulation of shoot architecture in trees. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2019, 47, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, T.; Guo, Y.; Cao, L.; Zhang, X.; Ali, S.; Ma, R.; Xie, L.; Wang, J.; Zinta, G. Naturally Occurring Epialleles and Their Roles in Response to Climate Change in Birch. Mol. Ecol. 2025, 34, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Xu, R.; Liu, B.; Han, Y.; Dong, W.; Xie, Q.; Tang, Z.; Lei, X.; Wang, C. BpGRP1 acts downstream of BpmiR396c/BpGRF3 to confer salt tolerance in Betula platyphylla. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Tu, R.; Ruan, Z.; Chen, C.; Peng, Z.; Zhou, X.; Sun, L.; Hong, Y.; Chen, D.; Liu, Q.; et al. Photoperiod and gravistimulation-associated Tiller Angle Control 1 modulats dynamic changes in rice plant architecture. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, T.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, N.; Dong, Z.; et al. A HST1-like gene controls tiller angle through regulating endogenous auxin in common wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Pierce, M.; Gailus-Durner, V.; Wagner, M.; Winter, E.; Vershon, A.K. Sum1 and Hst1 repress middle sporulation-specific gene expression during mitosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1999, 22, 6448–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, X. Evolution. molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms; S Kumar, G Stecher, M Li, C Knyaz, K Tamura. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cao, L.; Wu, S.; Yu, S.; Xie, L.n.; Li, H.; Jiang, J.; Liu, G. Establishment of high-efficiency genome editing in white birch (Betula platyphylla Suk.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Xue, W.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Yin, X.; Chen, B.; Qu, X.; Li, J. Mitotically heritable epigenetic modifications of CmMYB6 control anthocyanin biosynthesis in chrysanthemum. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Tang, J.; Chen, W.; Luo, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, W.; Yan, J.; Springer, N.M. An epiallele of a gene encoding a PfkB-type carbohydrate kinase affects plant architecture in maize. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, J.M.; Dardick, C. TILLER ANGLE CONTROL 1 modulates plant architecture in response to photosynthetic signals. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 4935–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, S.I.; Bald, T.; Onishi, T.; Xue, H.; Matsumura, T.; Kubo, R.; Takahashi, H.; Hippler, M.; Takahashi, Y. Configuration of Ten Light-Harvesting Chlorophyll a/b Complex I Subunits in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Photosystem I. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, C.; Riddle, R.; Toporik, H.; Da, Z.; Dobson, Z.; Williams, D.; Mazor, Y. The structure of the Physcomitrium patens photosystem I reveals a unique Lhca2 paralogue replacing Lhca4. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Lin, W.; Huang, C.; Fan, C.; Han, D.; Lu, D.; Xu, X.; Sui, S.; et al. Regulatory dynamics of the higher-plant PSI-LHCI supercomplex during state transitions. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1937–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoetzel, J.; Mant, A.; Haldrup, A.; Jensen, P.E.; Scheller, H.V. PSI-O, a new 10-kDa subunit of eukaryotic photosystem I. FEBS Lett. 2002, 510, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.T.H.; Schwier, C.; Elman, T.; Fleuter, V.; Zinzius, K.; Scholz, M.; Yacoby, I.; Buchert, F.; Hippler, M. Photosystem I light-harvesting proteins regulate photosynthetic electron transfer and hydrogen production. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, R.; Vishal, B.; Ramachandran, S.; Kumar, P.P. The OsPS1-F gene regulates growth and development in rice by modulating photosynthetic electron transport rate. Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 37, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiermaier, A.; Eilers, M. Transcriptional control: Calling in histone deacetylase. Curr. Biol. 1997, 7, R505–R507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Gong, F.; Liu, G.; Deng, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, W.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, X. Petal size is controlled by the MYB73/TPL/HDA19-miR159-CKX6 module regulating cytokinin catabolism in Rosa hybrida. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-C.; Lai, Z.; Fan, B.; Chen, Z. Arabidopsis WRKY38 and WRKY62 transcription factors interact with histone deacetylase 19 in basal defense. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2357–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davalos, V.; Esteller, M. MicroRNAs and cancer epigenetics: A macrorevolution. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2010, 22, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardinian, K.; Adashek, J.J.; Botta, G.P.; Kato, S.; Kurzrock, R. SMARCA4: Implications of an altered chromatin-remodeling gene for cancer development and therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 2341–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hou, L.; Li, B.; Ge, M.; Zheng, Z. Histone Deacetylase BpHST1 Regulates Plant Architecture and Photosynthesis in Birch. Biology 2025, 14, 1689. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121689

Hou L, Li B, Ge M, Zheng Z. Histone Deacetylase BpHST1 Regulates Plant Architecture and Photosynthesis in Birch. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1689. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121689

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Lili, Baoxin Li, Mengyan Ge, and Zhimin Zheng. 2025. "Histone Deacetylase BpHST1 Regulates Plant Architecture and Photosynthesis in Birch" Biology 14, no. 12: 1689. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121689

APA StyleHou, L., Li, B., Ge, M., & Zheng, Z. (2025). Histone Deacetylase BpHST1 Regulates Plant Architecture and Photosynthesis in Birch. Biology, 14(12), 1689. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121689