Niche Differentiation Characteristics of Phytoplankton Functional Groups in Arid Regions of Northwest China Based on Machine Learning

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

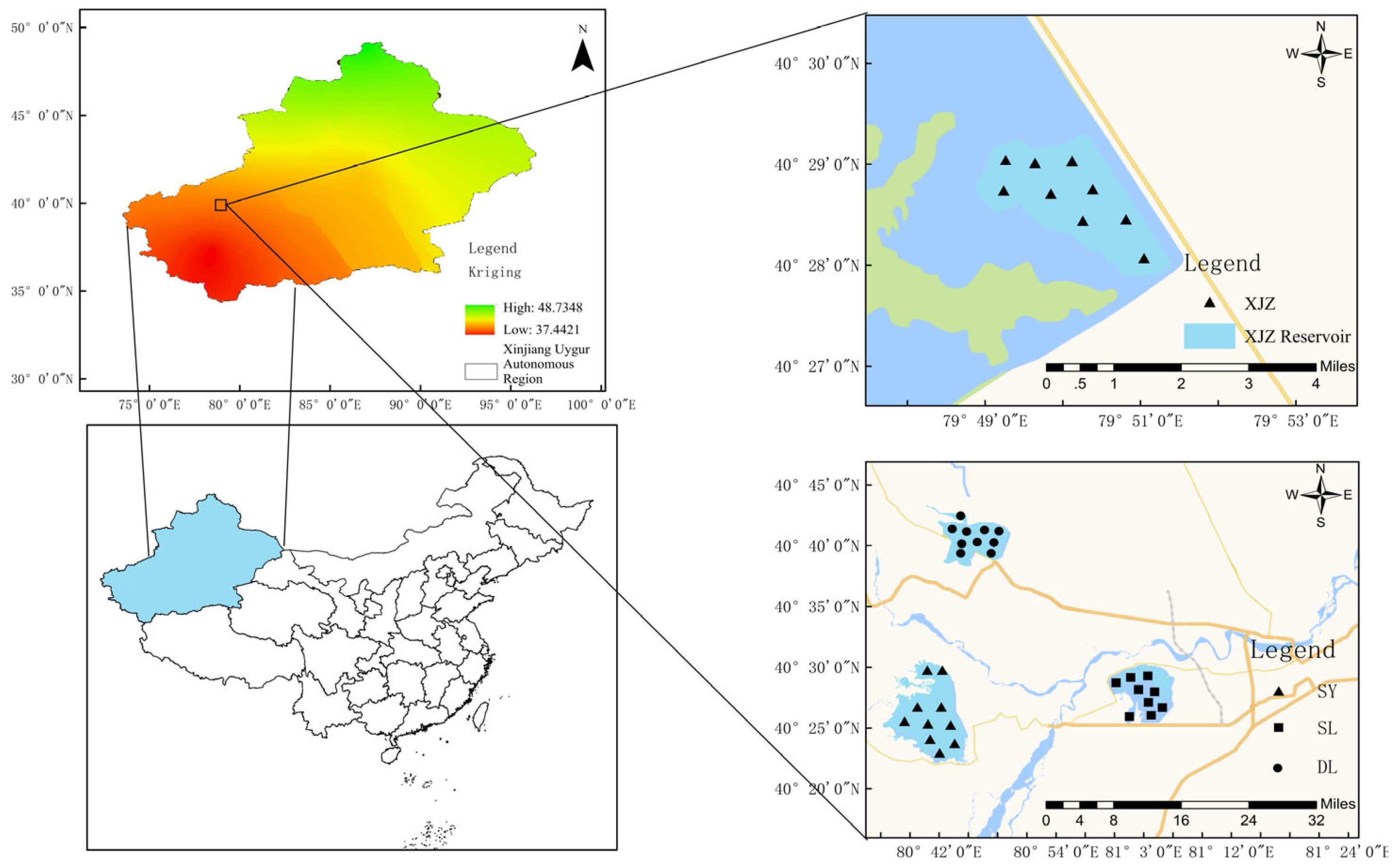

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Collection and Determination Methods

2.2.1. Physicochemical Indices of the Water

2.2.2. Phytoplankton

2.3. Division of Phytoplankton Functional Groups

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

2.4.1. Calculation of Dominant Species

2.4.2. Redundancy Analysis (RDA)

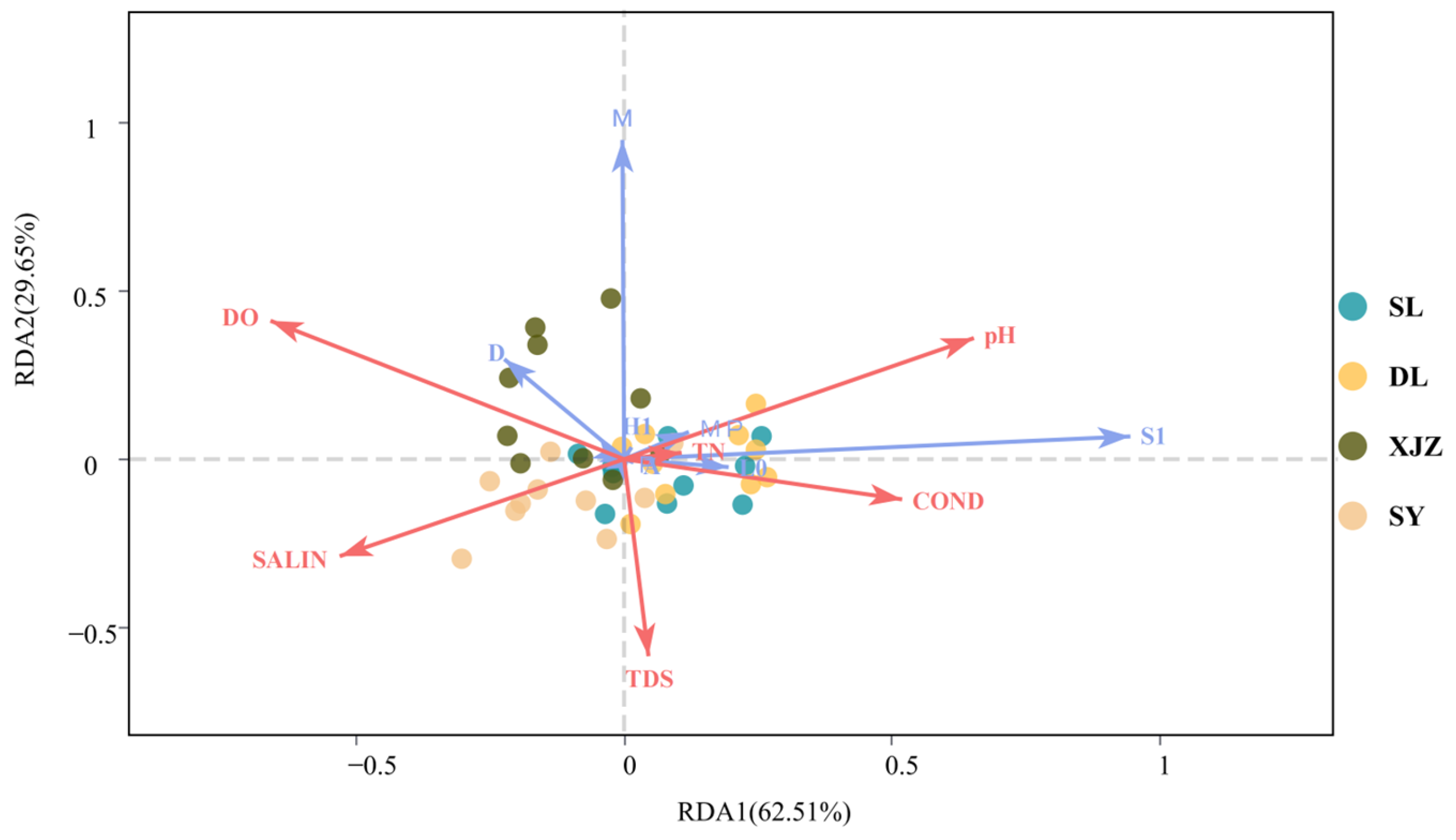

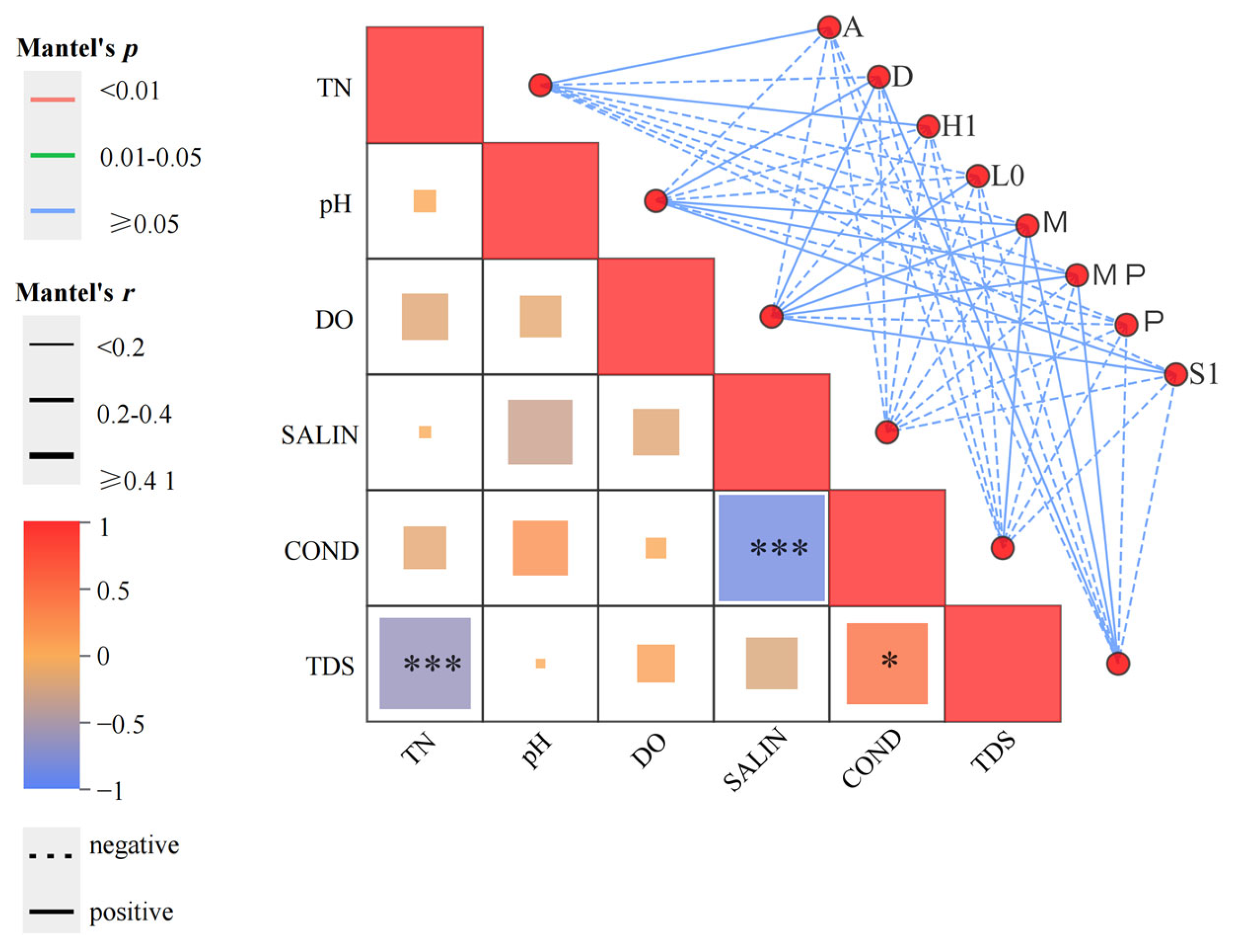

2.4.3. Correlation Analysis and Mantel Test Correlation Test

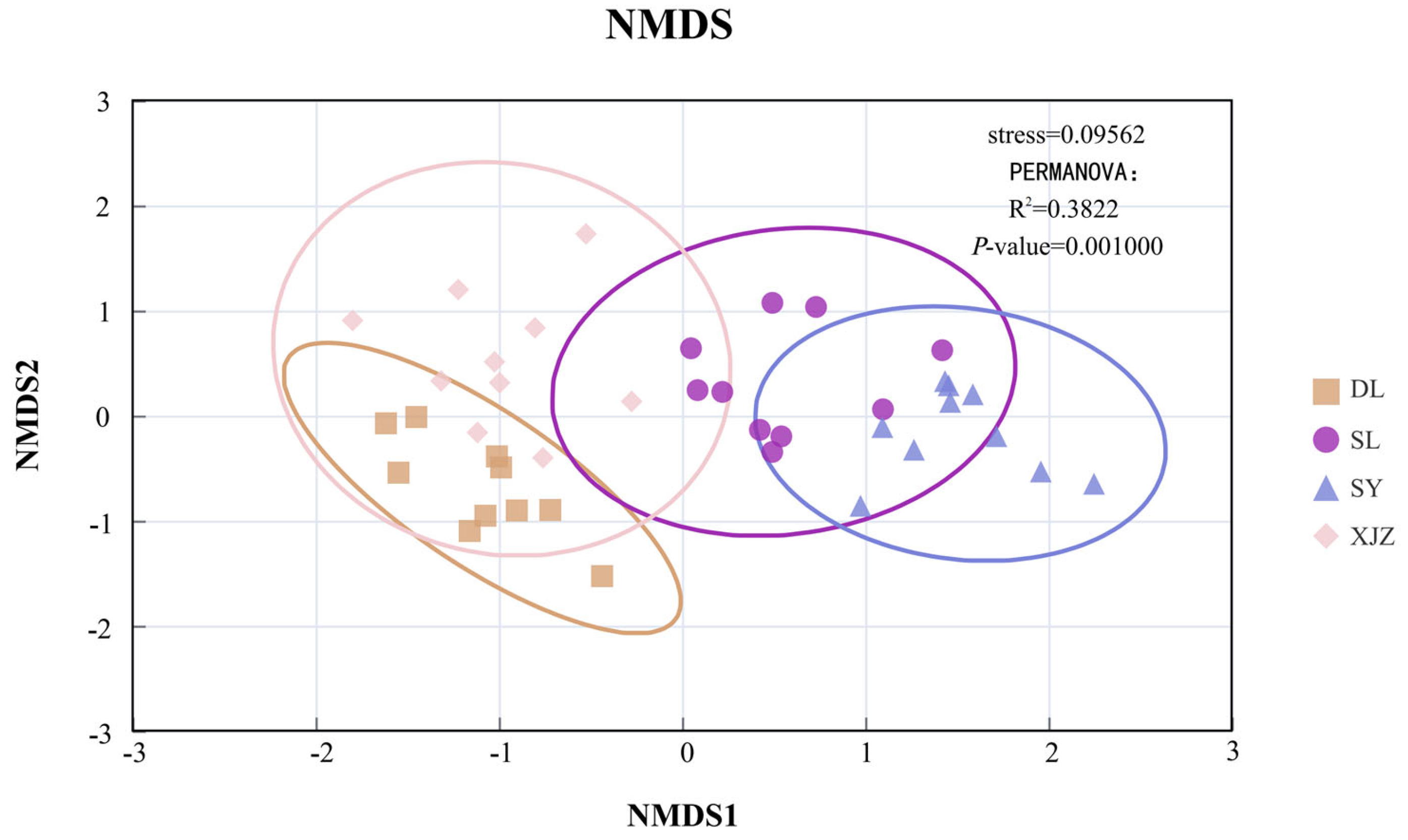

2.4.4. NMDS+PERMANOVA Analysis

2.4.5. Prediction of New Random Forest Model

2.4.6. Study on the Model of Niche Width and Interspecific Relationship

3. Results

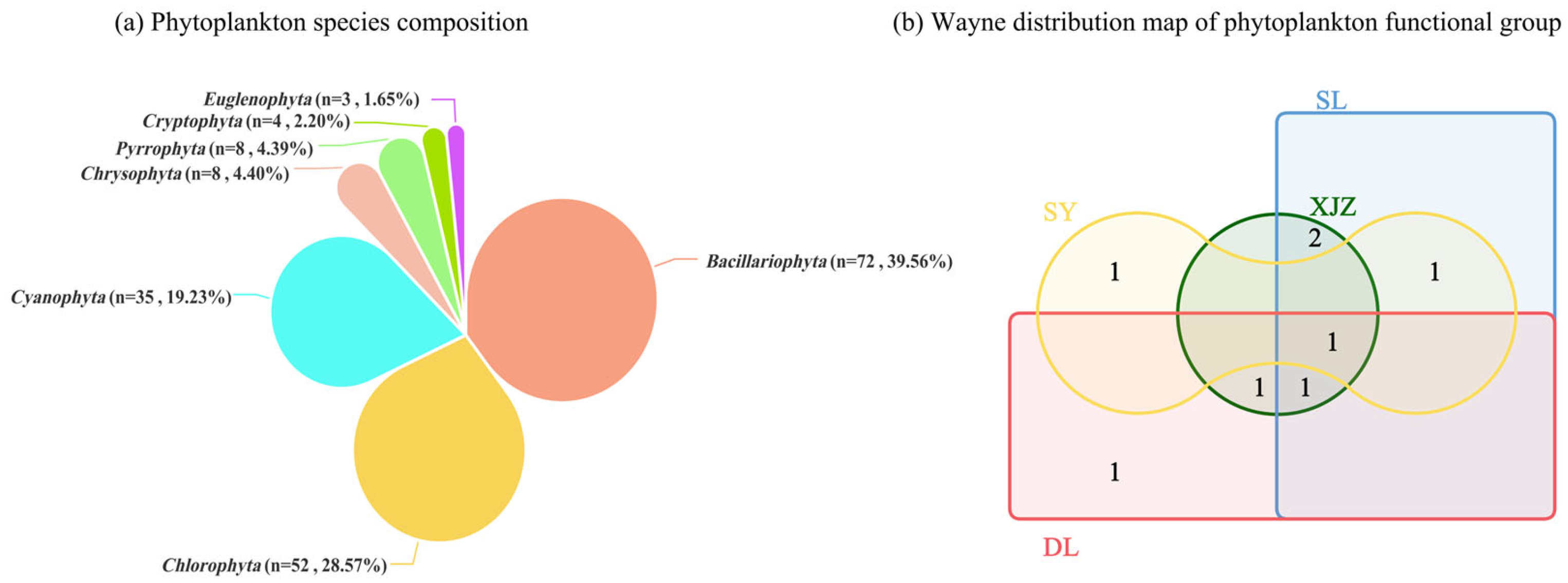

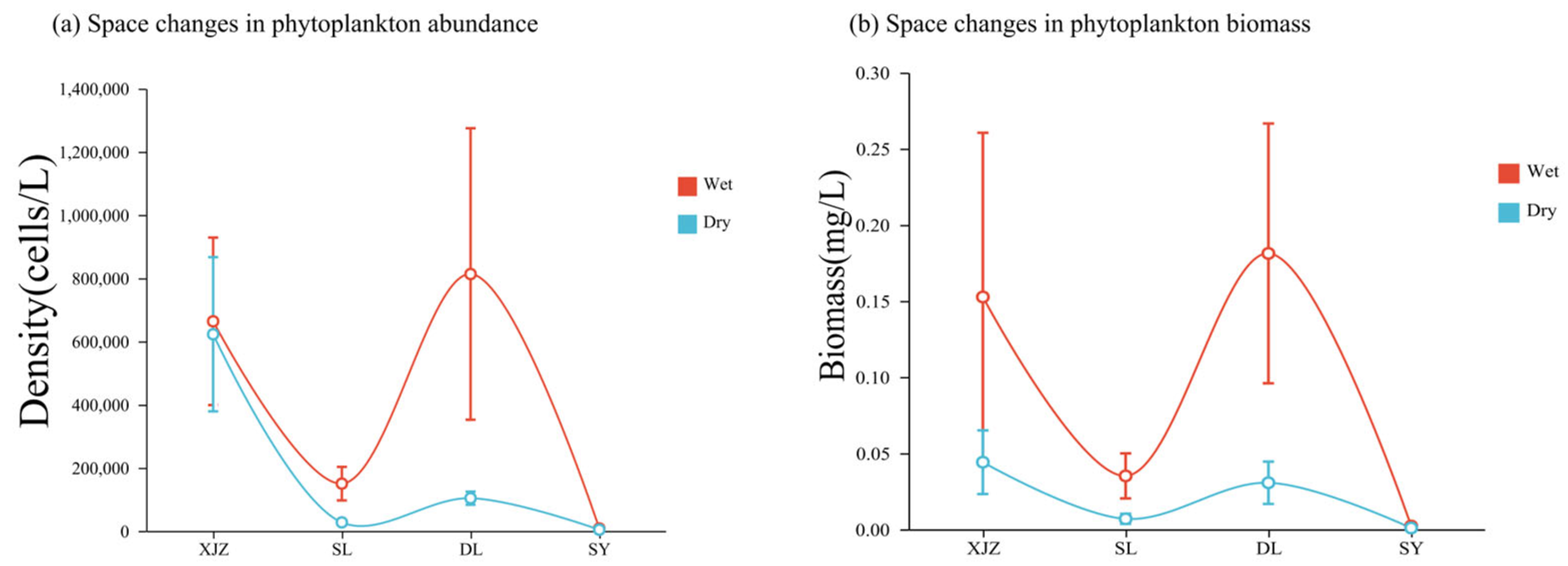

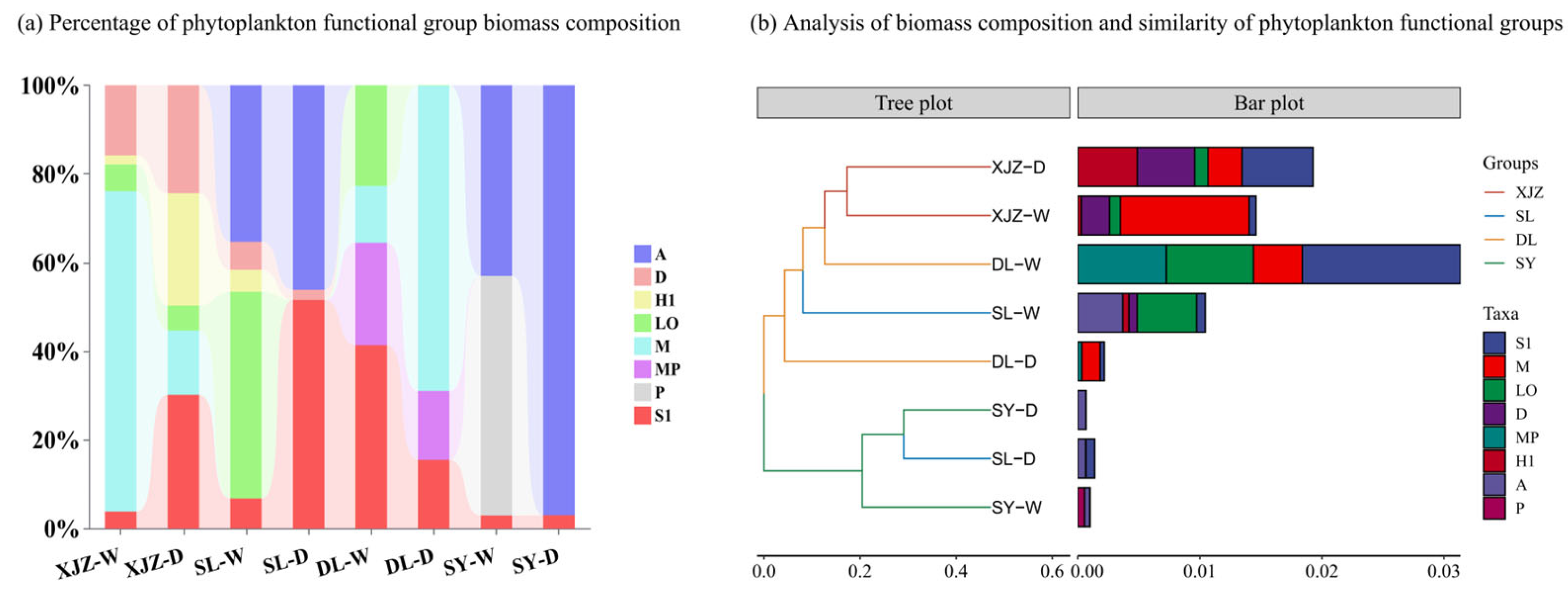

3.1. Composition of Functional Groups of Phytoplankton

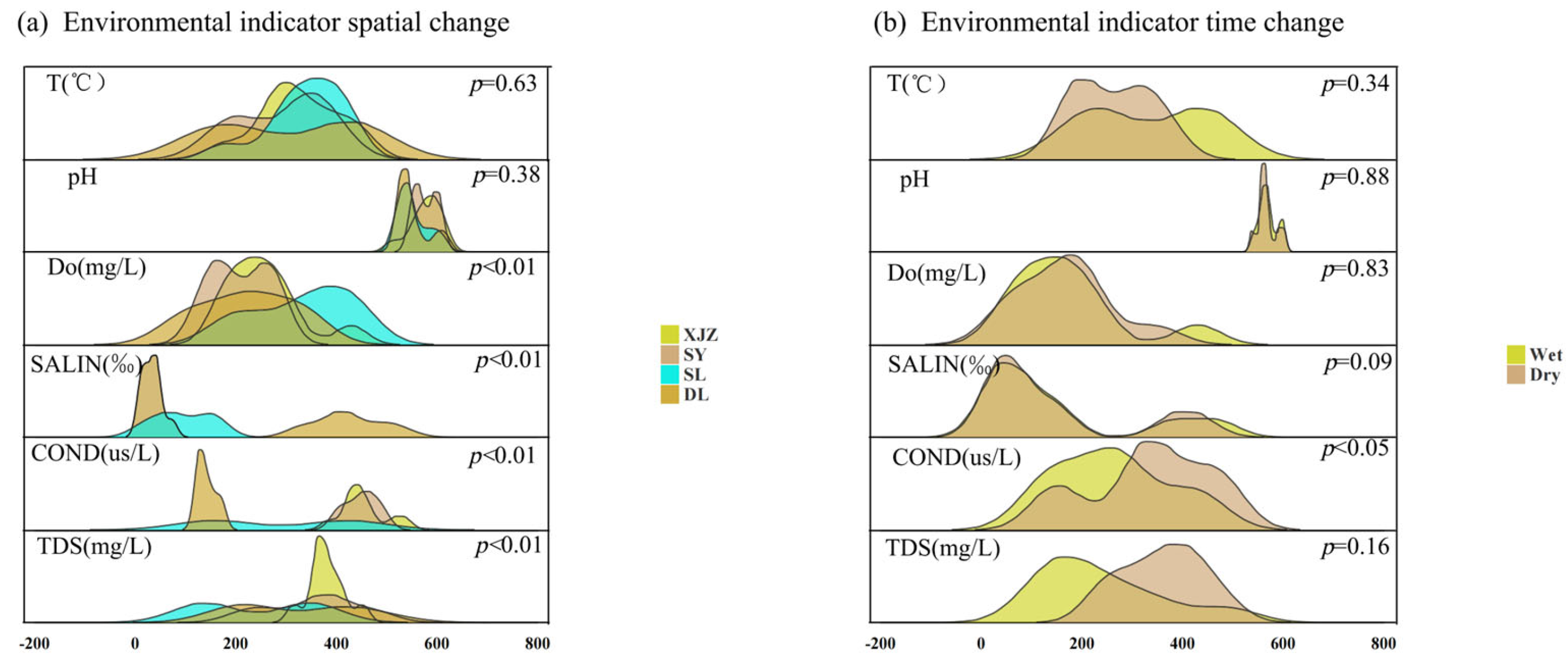

3.2. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Water-Body Environmental Factors

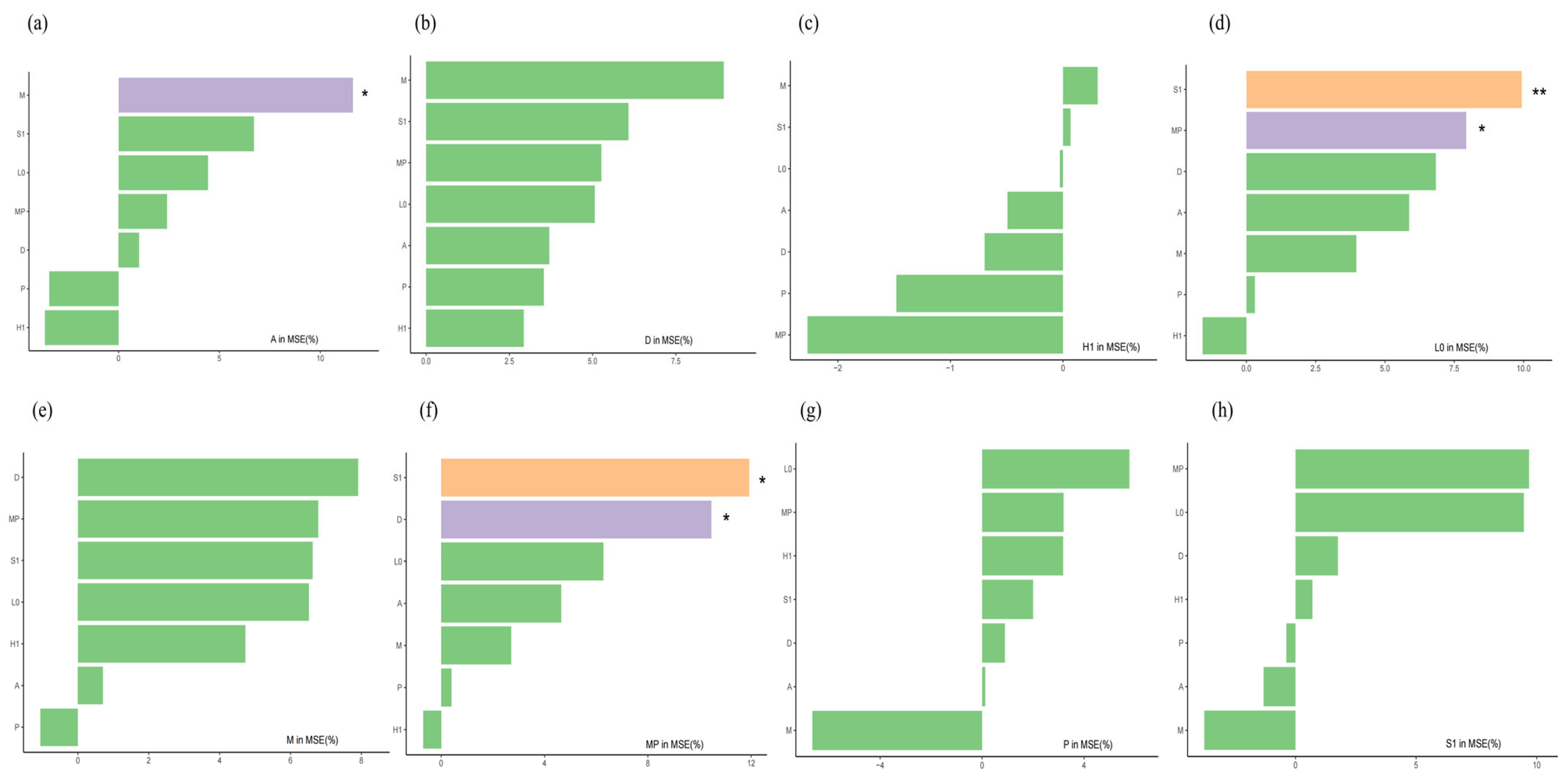

3.3. Quantitative Evaluation of the Functional Group Niche Contribution Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in the Structure of Phytoplankton Functional Groups in Arid Regions

4.2. Interactions Among Phytoplankton Functional Groups and Their Relationships with Aquatic Environmental Factors in Arid Regions

4.3. Niche Overlap Characteristics of Phytoplankton Functional Groups in Arid Regions

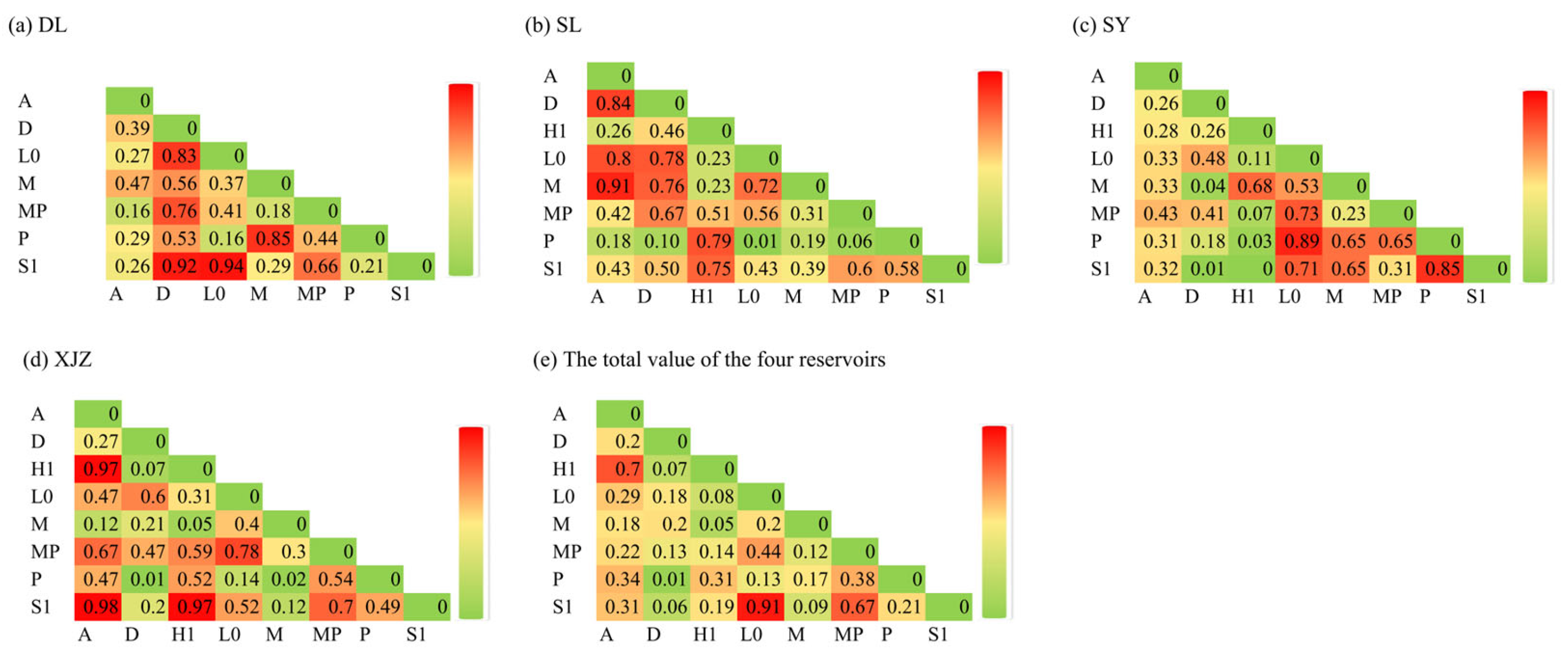

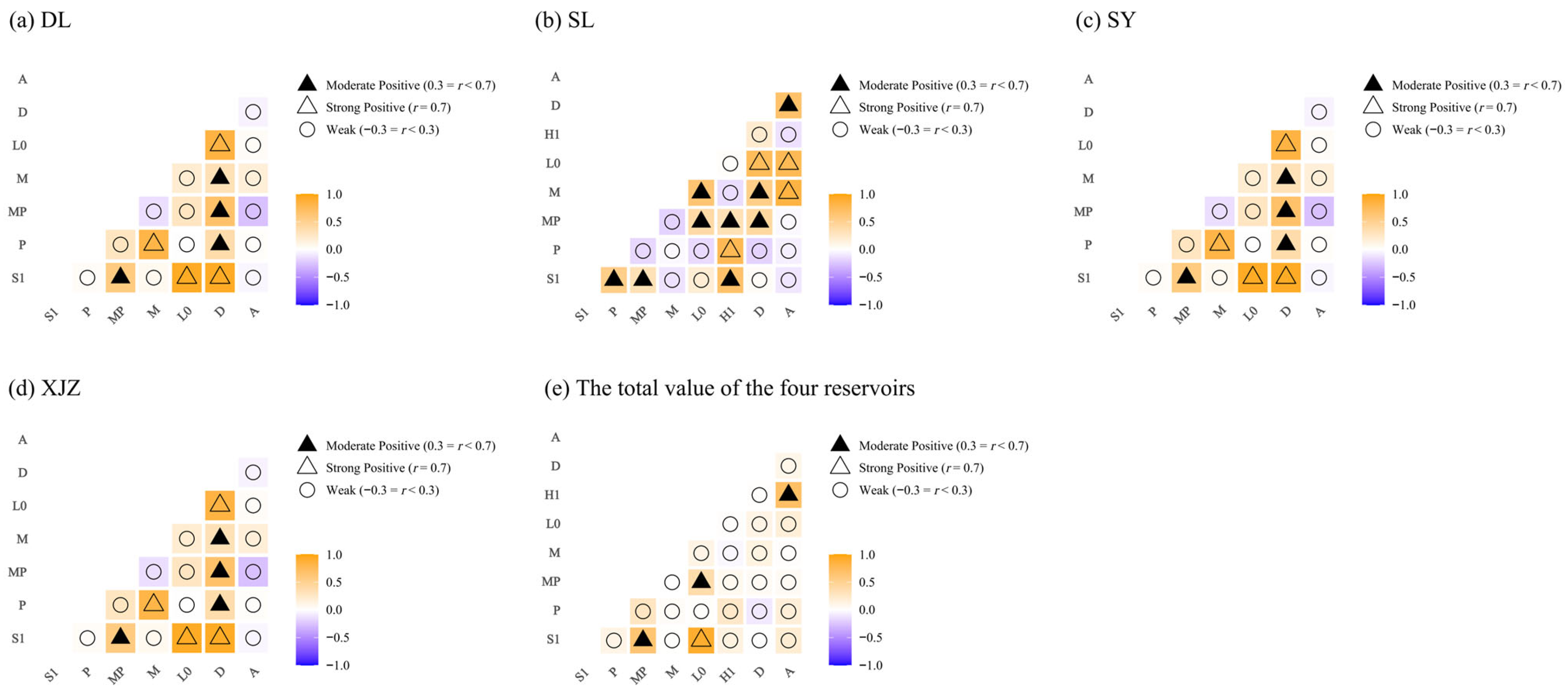

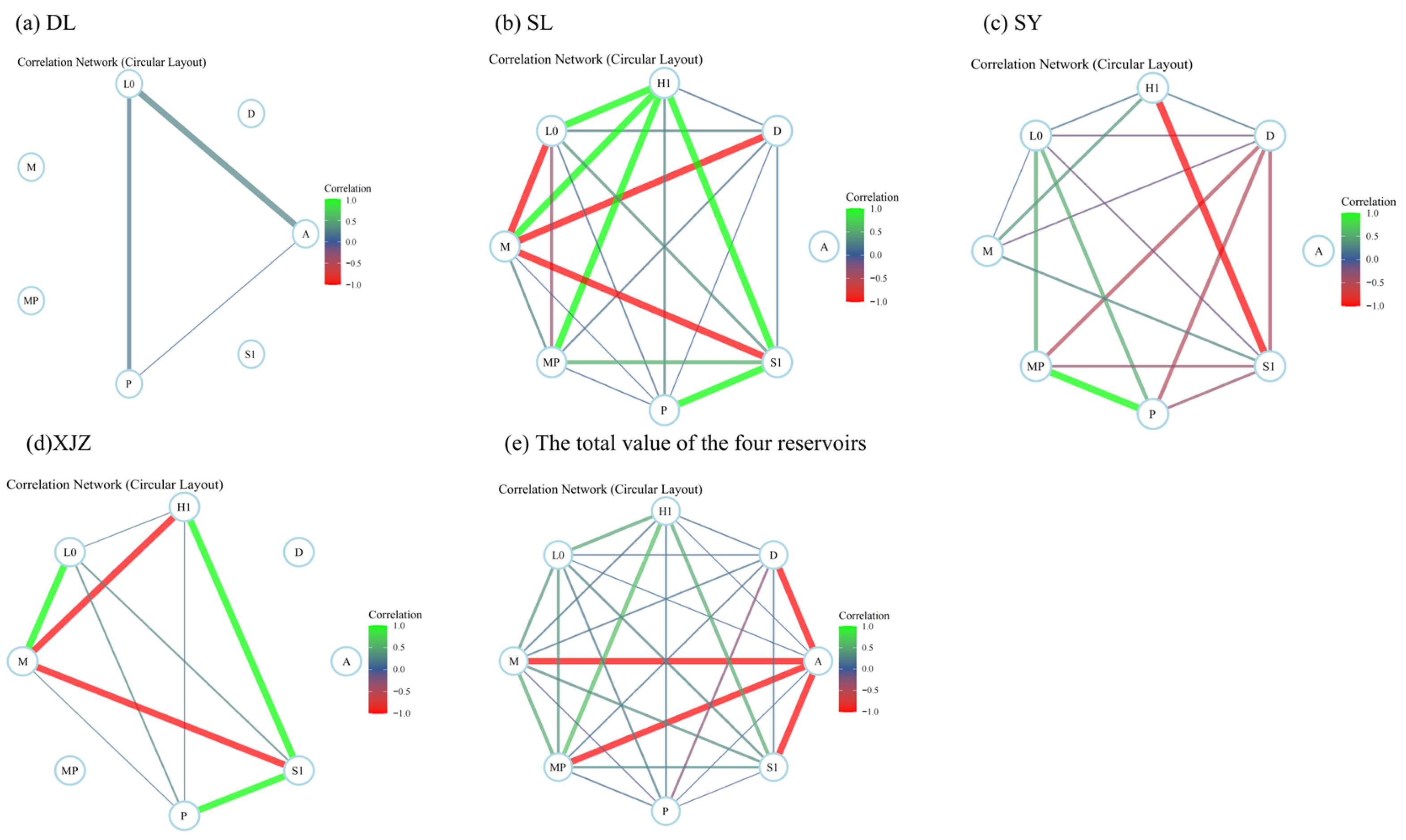

4.4. Overall Association and Interspecific Association of Dominant Phytoplankton Functional Groups in Arid Regions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, W.; Liu, T.; Chen, X. Seasonal changes of NDVI in the arid and semi-arid regions of Northwest China and its influencing factors. Arid Zone Res. 2023, 40, 1969–1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, R.; Li, Z.; Cai, C.; Wang, J. The dynamic response of splash erosion to aggregate mechanical breakdown through rain-fall simulation events in Ultisols (subtropical China). Catena 2014, 121, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Qian, C. Evaluation of historical and future precipitation changes in CMIP6 over the Tarim River Basin. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 150, 1659–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Chang, J.; Guo, A.; Wang, Y. Ecosystem variation and ecological benefits analysis of the mainstream of Tarim River. Arid Land Geogr. 2024, 47, 622–633. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Li, G.G.; Song, L.L. Historical changes of phytoplankton functional groups in Lake Fuxian, Lake Erhai and Lake Dianchi since 1960s. J. Lake Sci. 2014, 26, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chao, X.; Yang, S.S.; Liu, H.H.; Yan, B.B.; Wei, P.P.; Wu, X.X.; Ba, S. Mechanism and driving factors of phytoplankton community construction in the lower reaches of Yarlung Zangbo River. J. Lake Sci. 2024, 6, 24. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Reynolds, C.C.; Vera, H.; Carla, K. Towards a functional classification of the freshwater phytoplankton. J. Plankton Res. 2002, 24, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.Q.; Pan, B.B.; Ding, Y.Y. Characteristics and water quality evaluation of phytoplankton functional groups in the Weihe River mainstem and its tributaries in the northern foot of the Qinling Mountains. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 3226–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Yin, C.C.; Gong, L. Bottom-up and top-down effects on codetermination of the dominant phytoplankton functional groups in Lake Erhai. J. Lake Sci. 2023, 35, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, V.; Caputo, L.; Ordóez, J. Driving factors of the phytoplankton functional groups in a deep Mediterranean reservoir. Water Res. 2010, 44, 3345–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Peng, Y.Y.; Zou, X.X. Characteristics of phytoplankton functional groups and their relationships with environmental factors during extreme drought in Xinfengjiang Reservoir, Guangdong Province. J. Lake Sci. 2024, 36, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, B.B.; Zhang, H.H. Succession of Phytoplankton Functional Groups in the Wujiang River-reservoir System and Its Environmental Impact Factors Identification. Earth Environ. 2019, 47, 829–838. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Wang, C.C. Succession patterns of phytoplankton functional groups in western area of Yangcheng Lake and their relationship with environmental factors. China Environ. Sci. 2019, 39, 3027–3039. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, K.; Lu, K.K.; Xu, Z. Seasonal Succession of Phytoplankton Functional Groups and Their Driving Factors in the Sim-inghu Reservoir. Environ. Sci. 2018, 39, 2688–2697. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, W.; Shang, G.G. Succession Characteristics of Phytoplankton Functional Groups and Their Relationships with Environmental Factors in Dianshan Lake, Shanghai. Environ. Sci. 2018, 39, 3158–3167. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.C.Y.; Kuwabara, J.J.; Pasilis, S.S. Phosphate and Iron Limitation of Phytoplankton Biomass in Lake Tahoe. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1992, 49, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorendino, J.J.; Gaonkar, C.C.; Henrichs, D.D. Drivers of microplankton community assemblage following tropical cyclones. J. Plankton Res. 2023, 45, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffron, S.; Delage, E.; Budinich, M. Environmental vulnerability of the global ocean plankton community interactome. BioRxiv 2020, 11, 375295. [Google Scholar]

- Oleksy, I.I.; Beck, W.W.; Lammers, R.R. The role of warm, dry summers and variation in snowpack on phytoplankton dynamics in mountain lakes. Ecology 2020, 101, e03132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemergut, D.D.; Schmidt, S.S.; Fukami, T. Patterns and processes of microbial community assembly. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, Y.Y. Evolutionary Patterns of Meandering Morphology in the Middle Reach of the Mainstream Tarim River over the Past Decade. J. Changjiang River Sci. Res. Inst. 2025, 42, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Intra-annual variation analysis of runoff in the headstream area of Tarim River basin. South-North Water Transf. Water 2014, 12, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Shen, M.; Chen, J.; Xia, J.; Hong, S. Trends of natural runoffs in the Tarim River Basin during the last 60 years. Arid Land Geogr. 2018, 41, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, F. Water and Wastewater Monitoring and Analysis Methods, 4th ed.; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 88–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.H.; Wei, Y.Y. Systematics, Taxonomy and Ecology of Freshwater Algae in China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.Q.; Gao, Y.Y. Atlas of Common Freshwater Algae in Reservoirs of Important Drinking Water Sources in Guizhou Province; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.; Lan, Y.Y.; Xiao, L.L. The concepts, classification and application of freshwater phytoplankton functional groups. J. Lake Sci. 2015, 27, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padisák, J.; Crossetti, L.L.; Naselli-Flores, L. Use and misuse in the application of the phytoplankton functional classification: A critical review with update. Hydrobiologia 2009, 621, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.Y. Factors Influencing the Variation in Phytoplankton Functional Groups in Fuchunjiang Reservoir. Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Peng, J.; Xu, X. Survey-based approach to establish macrobenthic biological network in lakes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 162, 105061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, J.J.; Zhang, Y.Y. Community Structure Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Macrobenthos in Xiaoxingkai Lake and Surrounding Wetlands. Wetl. Sci. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Lucas-Borja, M.; Pandey, A.; Wang, T.; Huang, Z. Tree species richness and functional composition drive soil nitrification through ammonia-oxidizing archaea in subtropical forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 187, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.R.; Futuyma, D.D. On the measurement of niche breadth and overlap. Ecology 1971, 52, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schluter, D. A variance test for detecting species associations, with some example applications. Ecology 1984, 65, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.X.; Pan, C.C.; An, R.R. Niche and interspecific association of dominant phytoplankton species in different hydrological periods in the middle and lower reaches of Lhasa River, Tibet, China. J. Lake Sci. 2023, 35, 118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, D.D.; Yu, C.C.; Liu, H. Niche and interspecific association of major nekton in the sea area to the east of the Nanji Islands. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 30, 4249–4258. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Li, Y.Y.; Li, B.B. Seasonal Dynamics Characteristics and Affecting Physical Factors of Phytoplankton Functional Groups in the Dongjiang River. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2013, 37, 836–843. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.H.; Liu, P.P.; Wu, J.J. Phytoplankton Functional Groups and Their Response to Water Physiochemical Factors in Hongchaojiang Reservoir in Guangxi Province. J. Hydroecol. 2022, 43, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Pang, Y. Analysis of Driving Factors of Phytoplankton Community Based on Functional Groups and Applicability of Water Quality Assessment: A Case Study of Luoma Lake. Res. Environ. Sci. 2023, 36, 1915–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Min, W.W.; Wang, P.P.; Li, L.L. Relationship between Phytoplankton Functional Groups and Environmental Factors in the Wei River Basin. Res. Environ. Sci. 2015, 28, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Berman-Frank, I.; Lundgeren, P.; Falkowski, P. Nitrogen fixation and photosynthetic oxygen evolution in cyaobacteria. Res. Microbiol. 2003, 154, 64–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.C. The Ecology of Phytoplankton; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Xiong, F.; Lu, Y. Water quality and habitat drive phytoplankton taxonomic and functional group patterns in the Yangtze River. Ecol. Process. 2024, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutshinda, C.C.; Finkel, Z.Z.; Widdicombe, C.C.; Irwin, A.J. Ecological equivalence of species within phytoplankton functional groups. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naselli-Flores, L.; Barone, R. Phytoplankton dynamics and structure: A comparative analysis in natural and man-made water bodies of different trophic state. Hydrobiologia 2000, 438, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maegalef, R. Life forms of phytoplankton as survival alternatives in an unstable environment. Oceanol. Acta 1978, 1, 493–509. [Google Scholar]

- Borics, G.; Várbíró, G.; Grigorszky, I.; Krasznai, E.; Szabó, S.; Tihamer, K.K. A new evalution technique of potamoplankton for the assessement of the ecological status of rivers. Arch. Hydrobiol. Suppl. (Large Rivers 17) 2007, 161, 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Padisák, J.; Barbosa, F.F.R.; Koschel, R.; Krienitz, L. Deep layer cyanoprokaryota maxima in temperate and tropical lakes. Arch. Hydrobiol. Beih. Adv. Limnol. 2003, 58, 175–199. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Li, L.; Song, L.L. Annual dynamics of phytoplankton abundance and community structure in the Xionghe Reservoir. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2009, 29, 2971–2979. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, R.; Xiao, L.L. Comparative analysis of succession of the phytoplankton functional groups in two reservoirs with different hydrodynamics in Southern China. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2012, 21, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Valeriano-Riveros, M.; Vilaclara, G.; Castillo-Sandoval, F. Phytoplankton composition changes during water level fluctuations in a high-altitude, tropical reservoir. Inland Waters 2014, 4, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.W. Analysis of water resources balance in Tarim Irrigation District of Alar City. Tech. Superv. Water Resour. 2025, 5, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Caracciolo, M.; Grégory, B.; Beaugrand, P.H.; Hélaout, A. Annual phytoplankton succession results from niche-environment interaction. J. Plankton Res. 2020, 43, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy-László, Z.; Padisák, J.; Borics, G.; Abonyi, A.; B-Béres, V.; Várbíró, G. Analysis of niche characteristics of phytoplankton functional groups in fluvial ecosystems. J. Plankton Res. 2020, 42, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.C.; Sun, X.X.; Liu, Y.Y. Spatial niches of dominant zooplankton species in the Yantai offshore waters. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 5822–5833. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett, S.S.; Weitz, J.J.; Dam, H.H. Disentangling niche competition from grazing mortality in phytoplankton dilution experiments. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sooria, P.P.; Hatha, A.A.M.; Menon, N.N. Constraints in using relative biomass as a measure of competitive success in phytoplankton—A review. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2022, 557, 151819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burson, A.; Stomp, M.; Greenwell, E. Competition for nutrients and light: Testing advances in resource competition with a natural phytoplankton community. Ecology 2018, 99, 1108–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saros, J.J.; Anderson, N.N. The ecology of the planktonic diatom Cyclotella and its implications for global environmental change studies. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2015, 90, 522–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, U.; Peter, K.K.; Genitsaris, S. Do marine phytoplankton follow Bergmann’s rule sensu lato? Biol. Rev. 2016, 92, 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Lu, X.X.; Fan, Y.Y. Correlation between phytoplankton community patterns and environmental factors in Harbin section of the Songhua River. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.B.; Xu, B.; Wei, K.K. Phytoplankton community structure and its relation to environmental conditions in the middle Anning River, China. Chin. J. Ecol. 2020, 39, 3332–3341. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, N.; Li, H.; You, L.L. Succession of phytoplankton functional groups and driving variables in a young canyon reservoir. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, P.; Clark, A.; Hoffmann, P. Beyond nitrogen: Phosphorus—Estimating the minimum niche dimensionality for resource competition between phytoplankton. Ecol. Lett. 2025, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellar, P.P.; Paerl, H.H. Physiological adaptations in response to environmental stress during an N2-fixing Anabaena bloom. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1980, 40, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krinos, A.A.; Shapiro, S.S.; Li, W. Intraspecific Diversity in Thermal Performance Determines Phytoplankton Ecological Niche. Ecol. Lett. 2025, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.W.; Shen, H.; Zhou, M.M.; Zhou, W.W.; Zhang, S. Seasonal Analysis of Niche and Interspecific Association of Dominant Phytoplankton Species in Nanhai Lake, Baotou. China Environ. Sci. 2020, 40, 383–391. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Liu, Y.Y.; He, G.G. Niche Analysis of the Dominant Phytoplankton Species in Nanhai Lakes in Northwest China. J. Irrig. Drain. 2022, 41, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, X. Succession characteristics of phytoplankton functional groups and ecological assessment in a cold spring-type urban lake, China. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1435078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.L.; Qiu-Hua, L.L.; Shu-Lin, J. Response of Phytoplankton Functional Groups to Eutrophication in Summer at Xiaoguan Reservoir. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2015, 36, 4436–4443. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.Z.; Ma, Y.Y.; Zheng, J.J.; Liu, W.W.; Jin, Z.Z. Biodiversity of tree species, their populations’ spatial distribution pattern and interspecific association in mixed deciduous broadleaved forest in Changbai Mountains. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2004, 11, 2013–2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.W. Realized niches explain spatial gradients in seasonal abundance of phytoplankton groups in the South China Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 2018, 162, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Q. Greater niche overlap and species association of phytoplankton in dry season than in wet season in Wujiang River, Yungui Plateau, China. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2025, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacker, A.; Marzetz, V.; Spijkerman, E. Interspecific competition in phytoplankton drives the availability of essential mineral and biochemical nutrients. Ecology 2016, 96, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Dong, Z.; Guobin, F.F. Distribution and dynamics of niche and interspecific association of dominant phytoplankton species in the Feiyun River basin, Zhejiang, China. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2024, 42, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, L.L.; Yi, X.X.; Cao, W.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wu, P.P.; Ji, L.L. Analysis of interspecific associations among major tree species in three forest communities on the north slope of Changbai Mountain. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2015, 35, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, X.X.; Liu, Z.Z. Effects of Zooplankton Regulation on Phytoplankton. Ecol. Sci. 2014, 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Güthlich, L.; Oschlies, A. Phytoplankton niche generation by interspecific stoichiometric variation. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2012, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchaca, T.; Catalan, J. Nonlinearities in phytoplankton groups across temperate high mountain lakes. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.D.; Li, X.; Wang, X.X. Interspecific Association of Dominant Species of Phytoplankton in Ulansuhai Lake. Wetl. Sci. 2023, 21, 830–841. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.H.; Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.Y. Dynamic Analysis of Niche and Interspecific Association of Dominant Phytoplankton Species in Multi-Water-Source Reservoirs: A Case Study of Xiashan Reservoir in Shandong Province. J. Lake Sci. 2023, 35, 844–853. [Google Scholar]

- Hong-Run, T.T.; Jiao-Feng, L.L.; Li-Ting, Y. Interspecific associations of the main tree populations of the Cyclobalanopsis glauca community in Karst hills of Guilin, Southwest China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 30, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Yue, Z.; Yan, A.A. Niche and interspecific association of dominant bryophytes on different substrates. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Ye, X.X.; Ye, L.L.; Chen, X.X.; Zheng, S.S.; Chen, S.S.; Zhang, G.G.; Liu, B. Niche and interspecific association of dominant tree species in Michelia odora community. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 33, 2670–2678. [Google Scholar]

| Functional Group | Representative Species | Ecological Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| A * | Cyclotella sp. | Poor nutrition, cleanliness, deep water |

| D * | Synedra sp. Nitzschia sp. | Contains nutrients and low transparency |

| E | Dinobryon sp. | Poor or heterotrophic, small, shallow |

| F | Oocystis sp. | mesotrophic-eutrophic, clear-water lake |

| H1 * | Anabaena sp. | Rich in nutrients, stratified, low in nitrogen, shallow water |

| J | Scenedesmus sp. Actinastrum sp. | High nutrition, mixed, shallow water |

| K | Aphanocapsa sp. | Rich in nutrients, shallow waterRich in nutrients, shallow water |

| LO * | Merismopedia sp. Chroococcus sp. | Poor to eutrophic, medium to large water bodies |

| M * | Microcystis sp. | Small to medium, eutrophic to hypereutrophic |

| MP * | Navicula sp. Surirella sp. | Constant agitation, muddy water, shallow water |

| P * | Melosira sp. Closterium sp. | Medium nutrient, shallow water, thermocline |

| S1 * | Limnothrix sp. Planktothrix sp. | Medium richness, mixed turbidity, low transparency |

| SN | Raphidiopsis sp. | Warm, Mixed |

| X1 | Chlorella sp. Ankistrodesmus sp. | Overfertile, shallow water |

| X2 | Chlamydomonas sp. | Rich in nutrients, shallow water |

| Y | Cryptomonas sp. Cryptomonas ovata | High nutrition, mixed, shallow water |

| Reservoir | Reservoir Capacity (10,000 m3) | Water-Level Fluctuation (m) | Water Storage Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| DL | 7376.33 | 0.4 | Agricultural irrigation |

| SL | 6233.63 | 0.2 | Agricultural irrigation |

| SY | 10345.36 | 1.2 | Drinking water source, Ecological water supply |

| XJZ | 5678.33 | 0.4 | Agricultural irrigation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yun, L.; Zi, F.; Qiu, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Song, Y.; Chen, S. Niche Differentiation Characteristics of Phytoplankton Functional Groups in Arid Regions of Northwest China Based on Machine Learning. Biology 2025, 14, 1564. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111564

Yun L, Zi F, Qiu X, Liu Q, Zhang J, Yang L, Song Y, Chen S. Niche Differentiation Characteristics of Phytoplankton Functional Groups in Arid Regions of Northwest China Based on Machine Learning. Biology. 2025; 14(11):1564. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111564

Chicago/Turabian StyleYun, Long, Fangze Zi, Xuelian Qiu, Qi Liu, Jiaqi Zhang, Liting Yang, Yong Song, and Shengao Chen. 2025. "Niche Differentiation Characteristics of Phytoplankton Functional Groups in Arid Regions of Northwest China Based on Machine Learning" Biology 14, no. 11: 1564. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111564

APA StyleYun, L., Zi, F., Qiu, X., Liu, Q., Zhang, J., Yang, L., Song, Y., & Chen, S. (2025). Niche Differentiation Characteristics of Phytoplankton Functional Groups in Arid Regions of Northwest China Based on Machine Learning. Biology, 14(11), 1564. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111564