Elucidating the Molecular Basis of Thermal Stress Response in Juvenile Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) via an Integrative Transcriptome–Metabolome Approach

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Collection

2.2. RNA Isolation and Sequencing

2.3. Gene Ontology and KEGG Analysis

2.4. Metabolites Extraction and Analysis

2.5. Pathway Analysis

2.6. Association Analysis of Metabolome and Transcriptome

2.7. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

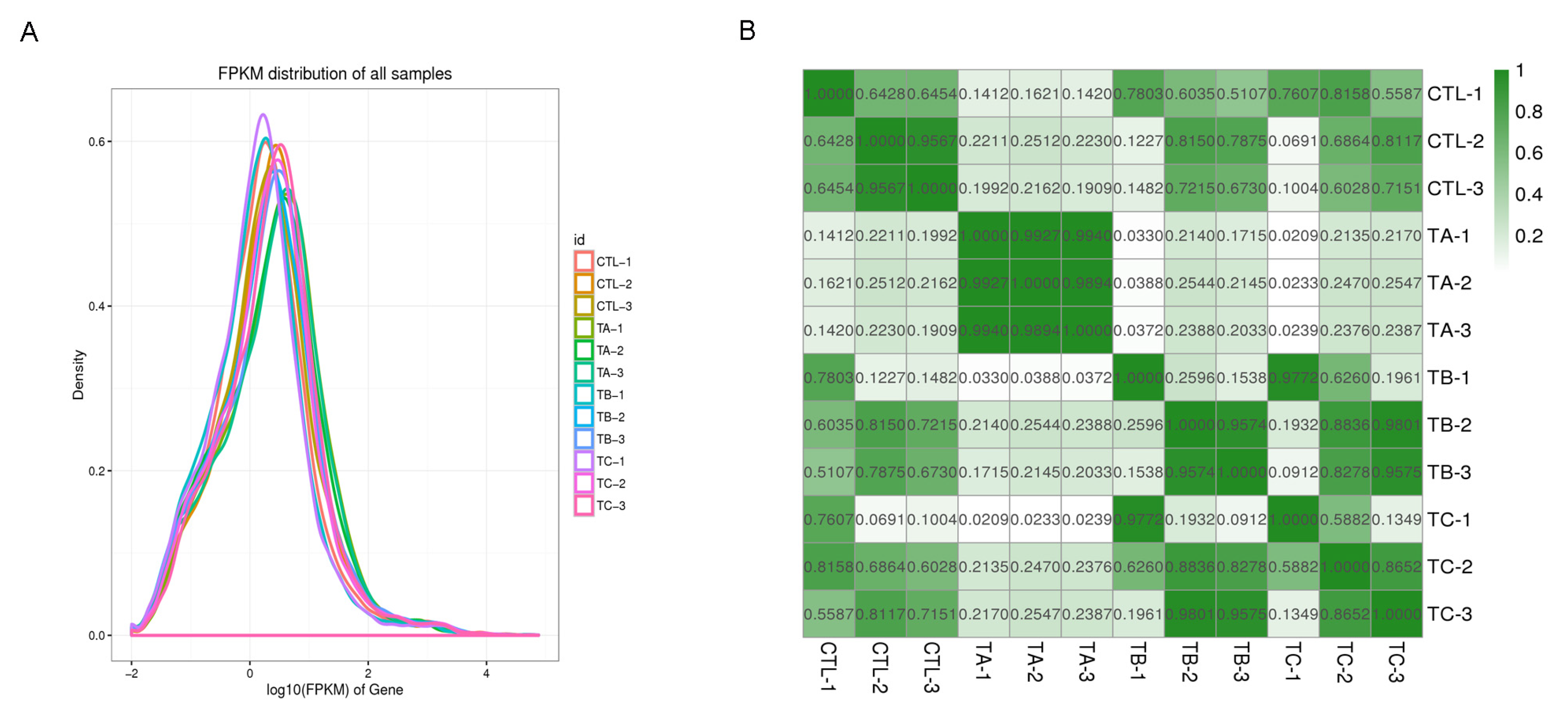

3.1. Transcriptome Sequencing and Data Analysis

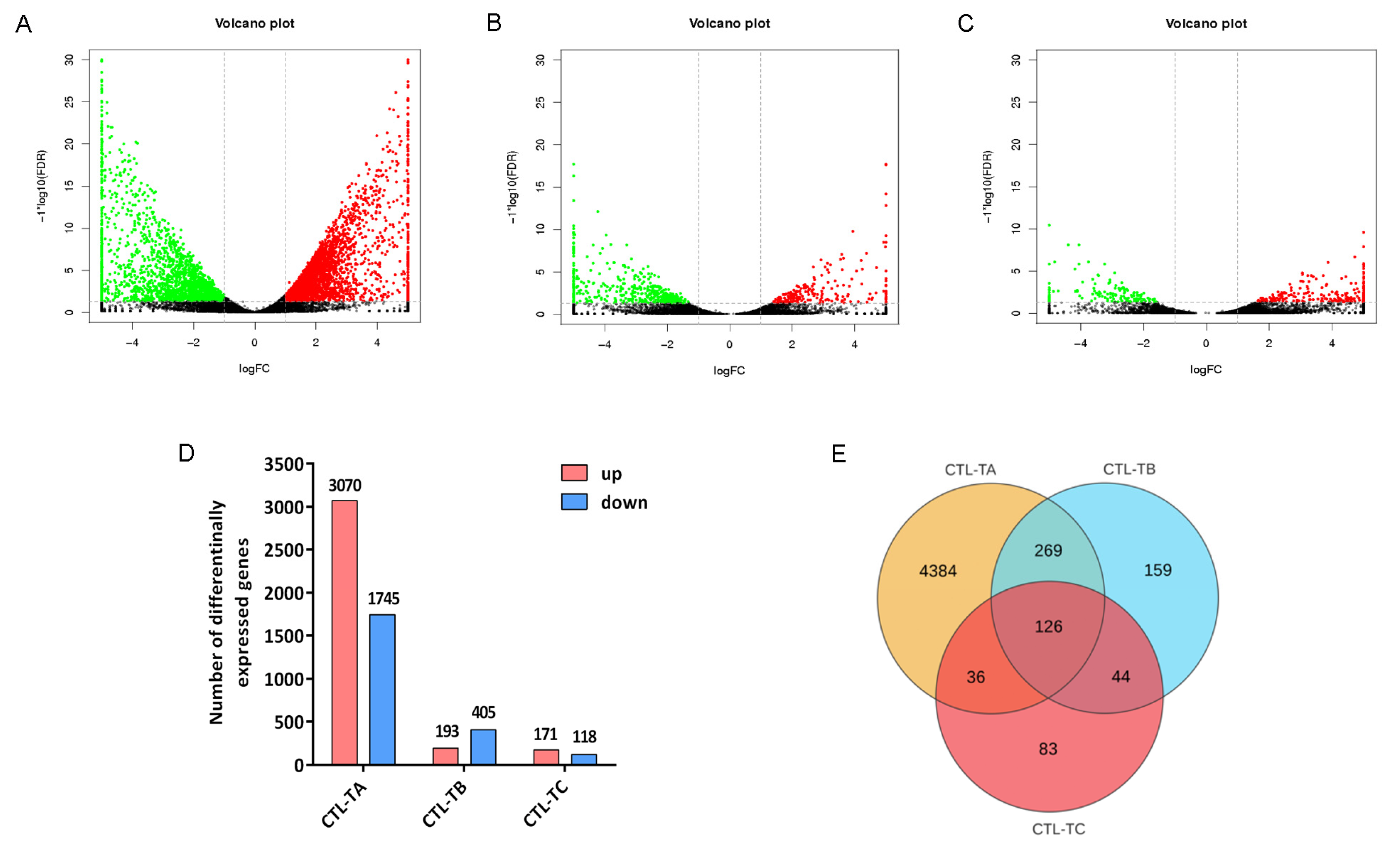

3.2. Differentially Expressed Genes Under High Temperatures in Turbot

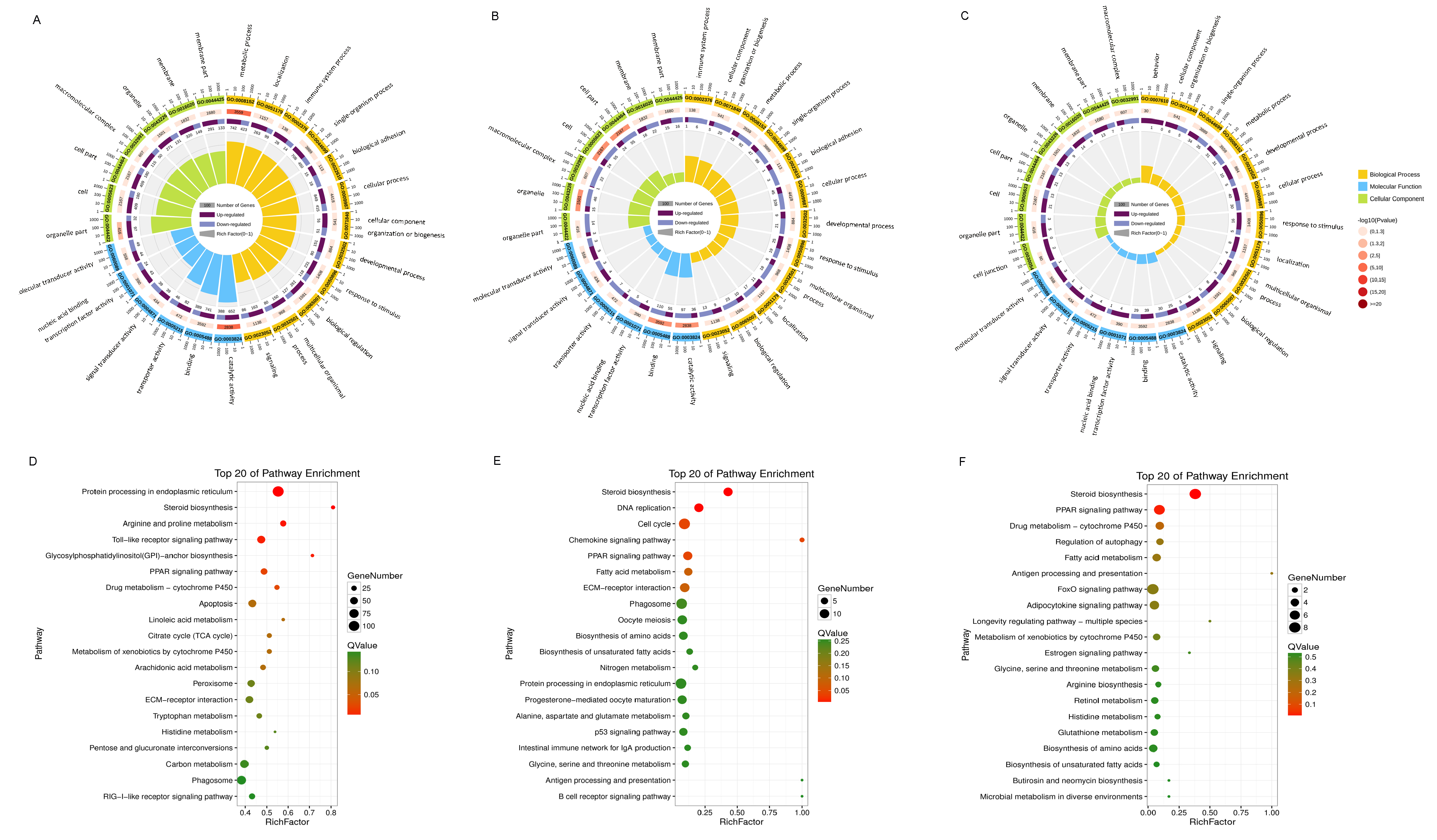

3.3. Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

3.4. Differential Metabolites Under High Temperatures in Turbot

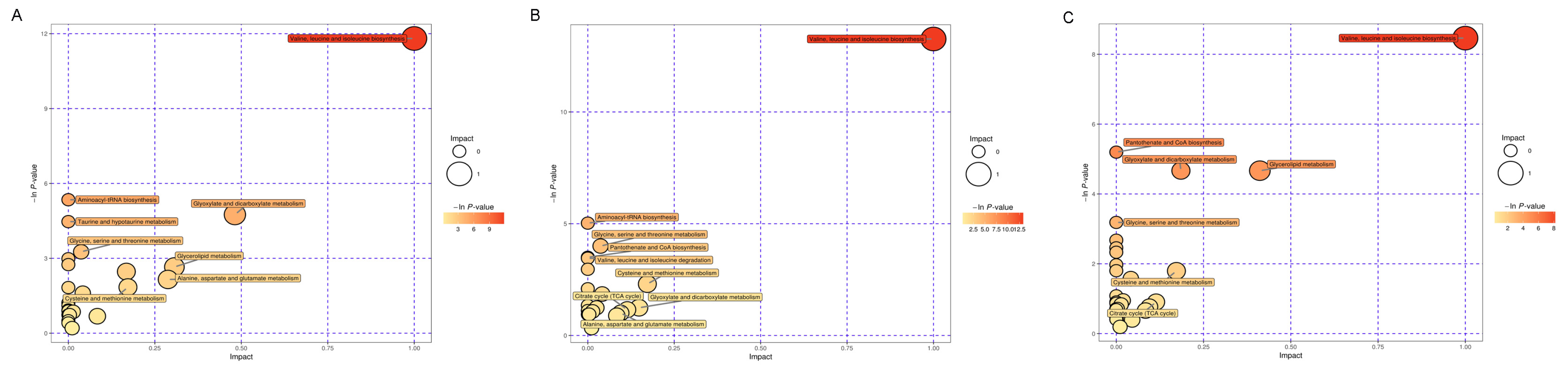

3.5. Pathway Analysis of Metabolites

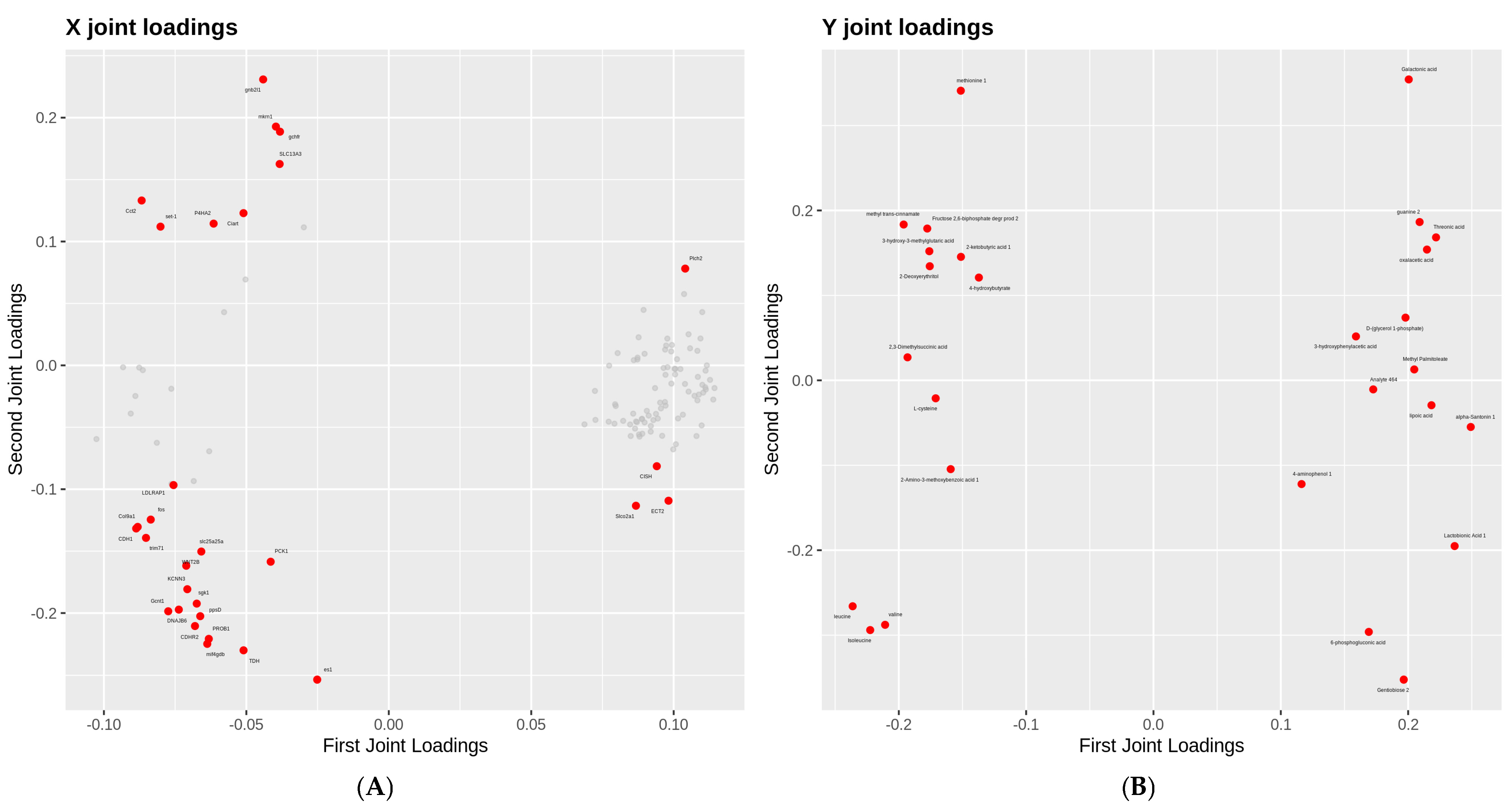

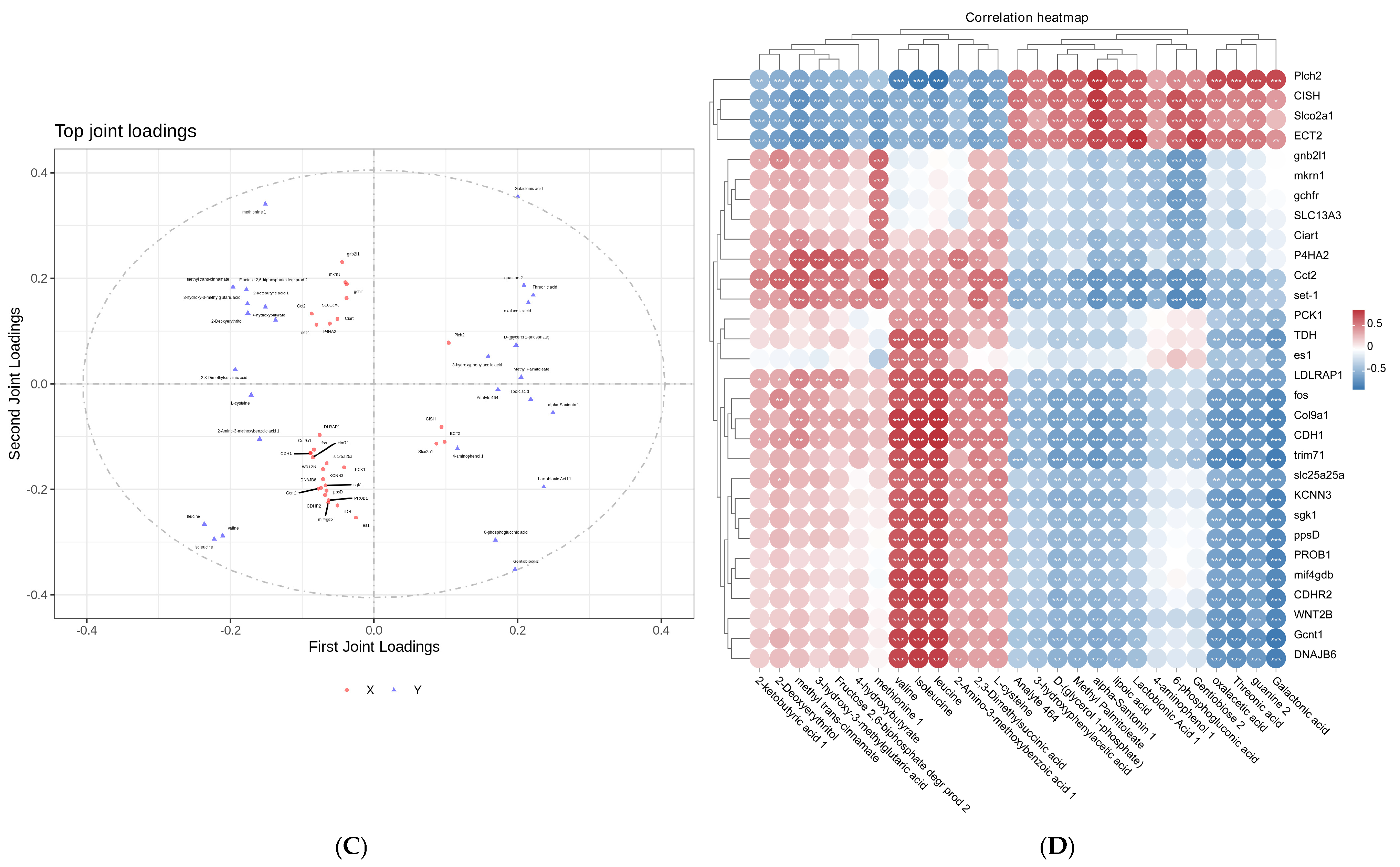

3.6. Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Profiling

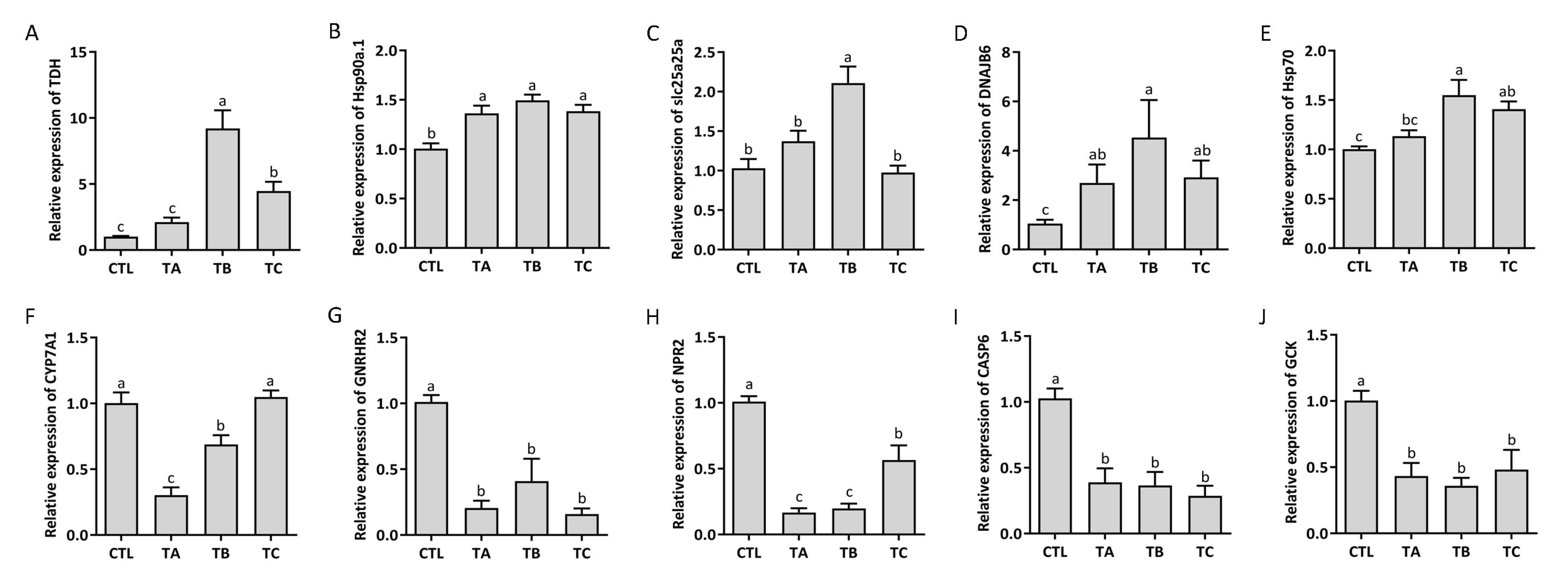

3.7. Identification of the Expression of DEGs by qPCR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, Q.X.; Lu, J.M.; Yang, Y.; Li, D.P.; Liu, J.Y. Acute Thermal Stress Reduces Skeletal Muscle Growth and Quality in Gibel Carp (Carassius gibelio). Water 2023, 15, 2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.O.; Ratko, J.; Côrrea, A.P.N.; da Silva, N.G.; Pereira, D.M.C.; Schleger, I.C.; Neundorf, A.K.A.; de Souza, M.; Herrerias, T.; Donatti, L. Assessing physiological responses and oxidative stress effects in Rhamdia voulezi exposed to high temperatures. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 50, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Kim, K.H.; Park, J.W.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.H. High water temperature-mediated immune gene expression of olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus according to pre-stimulation at high temperatures. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 101, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateus, A.P.; Costa, R.A.; Sadoul, B.; Bégout, M.L.; Cousin, X.; Canario, A.V.; Power, D.M. Thermal imprinting during embryogenesis modifies skin repair in juvenile European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 134, 108647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zahra, N.I.S.; Atia, A.A.; Elseify, M.M.; Abass, M.E.; Soliman, S. Dietary Pelargonium Sidoides extract mitigates thermal stress in Oreochromis niloticus: Physiological and immunological insights. Vet. Res. Commun. 2025, 49, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, S.; Arriagada-Solimano, M.; Escobar-Aguirre, S.; Palomino, J.; Aedo, J.; Estrada, J.M.; Barra-Valdebenito, V.; Zuloaga, R.; Valdes, J.A.; Dettleff, P. High temperature induces oxidative damage, immune modulation, and atrophy in the gills and skeletal muscle of the teleost fish black cusk-eel (Genypterus maculatus). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2025, 164, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korus, J.; Filgueira, R.; Grant, J. Influence of temperature on the behaviour and physiology of Atlantic salmon (Salmo Salar) on a commercial farm. Aquaculture 2024, 589, 740978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreibing, F.; Anslinger, T.M.; Kramann, R. Fibrosis in Pathology of Heart and Kidney: From Deep RNA-Sequencing to Novel Molecular Targets. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1013–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, R.; Grzelak, M.; Hadfield, J. RNA sequencing: The teenage years. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 631–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandereyken, K.; Sifrim, A.; Thienpont, B.; Voet, T. Methods and applications for single-cell and spatial multi-omics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 494–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Cao, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Luo, J.; Wang, B.; Zheng, H.; Weitz, D.A.; Zong, C. Droplet-based transcriptome profiling of individual synapses. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1332–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.H.; Ivanisevic, J.; Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics: Beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morville, T.; Sahl, R.E.; Moritz, T.; Helge, J.W.; Clemmensen, C. Plasma Metabolome Profiling of Resistance Exercise and Endurance Exercise in Humans. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Wang, D.; Dong, D.; Xu, L.; Xie, M.; Wang, Y.; Ni, T.; Jiang, W.; Zhu, X.; Ning, N.; et al. Altered intestinal microbiome and metabolome correspond to the clinical outcome of sepsis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Ma, D.; Yang, Y.S.; Yang, F.; Ding, J.H.; Gong, Y.; Jiang, L.; Ge, L.P.; Wu, S.Y.; Yu, Q.; et al. Comprehensive metabolomics expands precision medicine for triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zheng, G.; Peng, J.; Guo, M.; Wu, H.; Tan, Z. Integrative Inducer Intervention and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal the Metabolism of Paralytic Shellfish Toxins in Azumapecten farreri. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 6519–6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, X.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Gao, C.; Li, S.; Wei, C.; Huang, J.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, J.; Lu, J.; et al. Intratumor microbiome features reveal antitumor potentials of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2156255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.D.; Chen, X.T.; Wang, Z.Y.; Meng, Z.; Huang, B.; Guan, C.T. Physiological response of juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus L.) during hyperthermal stress. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Zhao, T.T.; Ma, A.J.; Huang, Z.H.; Liu, Z.F.; Cui, W.X.; Zhang, J.S.; Zhu, C.Y.; Guo, X.L.; Yuan, C.H. Metabolic responses in Scophthalmus maximus kidney subjected to thermal stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 103, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.T.; Ma, A.J.; Huang, Z.H.; Liu, Z.F.; Sun, Z.B.; Zhu, C.Y.; Yang, J.K.; Li, Y.D.; Wang, Q.M.; Qiao, X.W.; et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals that high temperatures alter modes of lipid metabolism in juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) liver. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D-Genom. Proteom. 2021, 40, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Q.; Yan, C.Y.; Xu, Y.; Qi, J.T.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, M.H.; Wu, Z.C.; Chan, J.L.; Liu, M.L.; Chen, L.B.; et al. Chromatin dynamics and transcriptional regulation of heat stress in an ectothermic fish. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2025, 292, 20250769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, W.W.; Kültz, D. Lost in translation? Evidence for a muted proteomic response to thermal stress in a stenothermal Antarctic fish and possible evolutionary mechanisms. Physiol. Genom. 2024, 56, 721–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.H.; Ma, A.J.; Yang, S.S.; Liu, X.F.; Zhao, T.T.; Zhang, J.S.; Wang, X.A.; Sun, Z.B.; Liu, Z.F.; Xu, R.J. Transcriptome analysis and weighted gene co-expression network reveals potential genes responses to heat stress in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D-Genom. Proteom. 2020, 33, 100632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.Y.; Chen, J.Z.; Huang, W.J.; Huang, G.; Deng, M.Y.; Hong, S.M.; Ai, P.; Gao, C.; Zhou, H.K. OmicShare tools: A zero-code interactive online platform for biological data analysis and visualization. Imeta 2024, 3, e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.H.; Guo, X.L.; Wang, Q.M.; Ma, A.J.; Zhao, T.T.; Qiao, X.W.; Li, M. Digital RNA-seq analysis of the cardiac transcriptome response to thermal stress in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). J. Therm. Biol. 2022, 104, 103141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.H.; Liu, L.X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Qi, Y.; Xie, L.; Zhang, C.M.; Yao, G.Q.; Bu, P.L. Fibulin7 Mediated Pathological Cardiac Remodeling through EGFR Binding and EGFR-Dependent FAK/AKT Signaling Activation. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2207631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, P.P.; Chakraborty, P.; Dash, S.P.; Ikeuchi, T.; de Vega, S.; Ambatipudi, K.; Wahl, L.; Yamada, Y. Cell adhesion protein fibulin-7 and its C-terminal fragment negatively regulate monocyte and macrophage migration and functions in vitro and in vivo. Faseb J. 2018, 32, 4889–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Xu, L.; Song, H.; Feng, J.; Zhou, C.; Yang, M.J.; Shi, P.; Li, Y.R.; Guo, Y.J.; Li, H.Z.; et al. Effect of heat and hypoxia stress on mitochondrion and energy metabolism in the gill of hard clam. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C-Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 266, 109556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.H.; Xu, Y.Q.; Fu, W.M.; Li, H.B.; Li, G.M.; Li, J.C.; Wang, W.T.; Tao, L.X.; Chen, T.T.; Fu, G.F. RGA1 Negatively Regulates Thermo-tolerance by Affecting Carbohydrate Metabolism and the Energy Supply in Rice. Rice 2023, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.Z.; Wang, Y.X.; Lin, S.R.; Li, H.F.; Qi, P.Z.; Buttino, I.; Wang, W.F.; Guo, B.Y. Insights into the Response in Digestive Gland of Mytilus coruscus under Heat Stress Using TMT-Based Proteomics. Animals 2023, 13, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, A.; Paliwal, V.; Jain, S.; Paliwal, S.; Sharma, S. Current Insight on the Role of Glucokinase and Glucokinase Regulatory Protein in Diabetes. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, D.; Dsouza, V.S.; Al-Mulla, F.; Al Madhoun, A. New-Generation Glucokinase Activators: Potential Game-Changers in Type 2 Diabetes Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, H.M.; Garruss, A.; Shilatifard, A. SET for life: Biochemical activities and biological functions of SET domain-containing proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013, 38, 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; Hu, X.; Kalvakolanu, D.V.; Ren, H.; Guo, B. Roles for the methyltransferase SETD8 in DNA damage repair. Clin. Epigenetics 2022, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Wu, Q.; Cheng, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhu, M.; Miao, C. High Glucose Induces Endothelial COX2 and iNOS Expression via Inhibition of Monomethyltransferase SETD8 Expression. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 2308520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, J.; Jie, W. Methyltransferase SET domain family and its relationship with cardiovascular development and diseases. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue bao. Yi Xue Ban = J. Zhejiang University. Med. Sci. 2022, 51, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzger, D.C.H. Epigenetic mechanisms in response to environmental change. In Encyclopedia of Fish Physiology, 2nd ed.; Alderman, S.L., Gillis, T.E., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 198–211. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.J.; Zhou, T.; Gao, D.Y. Genetic and epigenetic regulation of growth, reproduction, disease resistance and stress responses in aquaculture. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 994471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.Y.J.; Wang, S.S.; Yu, Q.; Wang, M.; Ge, F.; Li, S.S.; Yu, X.L. Cla4 phosphorylates histone methyltransferase Set1 to prevent its degradation by the APC/CCdh1 complex. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, S.; Fukuwatari, T. Physiological Functions of Proteinogenic Amino Acid. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2022, 68, S28–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Peng, H.F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.S. Comprehensive review of amino acid transporters as therapeutic targets. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 129646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Feng, Y.; Liu, B.; Xie, W. Estrogen sulfotransferase and sulfatase in steroid homeostasis, metabolic disease, and cancer. Steroids 2024, 201, 109335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happi, G.M.; Teufel, R. Steroids from the Meliaceae family and their biological activities. Phytochemistry 2024, 221, 114039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Choudhary, M.; Chandra, R.K.; Bhardwaj, A.K.; Tripathi, M.K. Sex steroids exert a suppressive effect on innate and cell mediated immune responses in fresh water teleost, Channa punctatus. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2019, 100, 103415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otarigho, B.; Aballay, A. Cholesterol Regulates Innate Immunity via Nuclear Hormone Receptor NHR-8. Iscience 2020, 23, 101068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Xu, C.; Jiang, N.; Meng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xue, M.Y.; Liu, W.Z.; Li, Y.Q.; Fan, Y.D. Transcriptomics in rare minnow (Gobiocypris rarus) towards attenuated and virulent grass carp reovirus genotype II infection. Animals 2023, 13, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Chen, J.D.; Dong, X.H.; Yang, Q.H.; Liu, H.Y.; Zhang, S.; Xie, S.W.; Zhang, W.; Deng, J.M.; Tan, B.P.; et al. Protective effect of steroidal saponins on heat stress in the liver of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) revealed by metabolomic analysis. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 33, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Wu, Z.; He, Y.J.; Li, X.H.; Li, J. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Impaired Fertility and Immunity Under Salinity Exposure in Juvenile Grass Carp. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 697813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, L.H.H.; Chen, X.T.; Jumbo, J.C.C.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Z.Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.F. Cardiomyocyte mitochondrial dynamic-related lncRNA 1 (CMDL-1) may serve as a potential therapeutic target in doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 25, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabalina, I.G.; Edgar, D.; Gibanova, N.; Kalinovich, A.V.; Petrovic, N.; Vyssokikh, M.Y.; Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. Enhanced ROS Production in Mitochondria from Prematurely Aging mtDNA Mutator Mice. Biochem. Mosc. 2024, 89, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.P.; Song, L.; Xie, H.; Zhu, J.Y.; Li, W.; Xu, G.Y.; Cai, L.J.; Han, X.X. In Situ and Real-Time Monitoring of Mitochondria-Endoplasmic Reticulum Crosstalk in Apoptosis via Surface-Enhanced Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 8363–8369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, C.X.; Yang, Z.H.; Huang, C.L.; Jiao, K.Z.; Yang, L.; Duan, C.Y.; Zhang, Z.X.; Li, G.L. Effects of Chronic Heat Stress on Growth, Apoptosis, Antioxidant Enzymes, Transcriptomic Profiles, and Immune-Related Genes of Hong Kong Catfish (Clarias fuscus). Animals 2024, 14, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Feng, M.; Li, Z.; Zhou, M.; Xu, L.; Pan, K.; Wang, S.; Su, W.; Zhang, W. ETV5 Regulates Hepatic Fatty Acid Metabolism Through PPAR Signaling Pathway. Diabetes 2021, 70, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Gao, Y.; Qu, A.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Xie, G.; Yao, X.; Yang, X.; Zhu, S.; Yagai, T.; et al. YAP-TEAD mediates PPAR α-induced hepatomegaly and liver regeneration in mice. Hepatology 2022, 75, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Z.; Nie, G.; Dai, Y. Role of oxidative stress and inflammation-related signaling pathways in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2023, 21, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Liu, S.J.; Qi, D.L.; Qi, H.F.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Tian, F. Genome-wide identification and expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gene family in the Tibetan highland fish Gymnocypris przewalskii. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 48, 1685–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Tang, X.; Ji, R.L.; Xiang, X.J.; Liu, Q.D.; Han, S.Z.; Du, J.L.; Li, Y.R.; Mai, K.S.; Ai, Q.H. Adiponectin receptor agonist AdipoRon regulates glucose and lipid metabolism via PPARγ signaling pathway in hepatocytes of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2025, 1870, 159632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, A.; Tang, S.S.; Huang, M.X.; Yu, Q.R.; Xu, C.; Li, E.R. Identification of key overlapping DEGs and molecular pathways under multiple stressors in the liver of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D-Genom. Proteom. 2023, 48, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, F.; Zhao, L.; Ma, R.L.; Wang, J.; Du, L.Q. FoxO signaling and mitochondria-related apoptosis pathways mediate tsinling lenok trout (Brachymystax lenok tsinlingensis) liver injury under high temperature stress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 251, 126404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, M.M.; de Macedo, G.T.; Prestes, A.S.; Ecker, A.; Müller, T.E.; Leitemperger, J.; Fontana, B.D.; Ardisson-Araújo, D.M.P.; Rosemberg, D.B.; Barbosa, N.V. Modulation of redox and insulin signaling underlie the anti-hyperglycemic and antioxidant effects of diphenyl diselenide in zebrafish. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 158, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Liu, M.L.; Liu, Y.M.; Wang, J.F.; Zhang, D.; Niu, H.B.; Jiang, S.W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.S.; Han, B.S.; et al. Transcriptome comparison reveals a genetic network regulating the lower temperature limit in fish. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.R.; Li, J.L.; Xu, Y.F.; Jiang, G.; Su, S.Y.; Zhang, Z.H.; Jia, R.; Tang, Y.K. Effects of starvation-refeeding on antioxidant status, metabolic function, and adaptive response in the muscle of Cyprinus carpio. Aquaculture 2025, 602, 742372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Primer | Sequences | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TDH | Forward | CCATCCCAAGGTGCTCATCA | 61.2 |

| Reverse | CCGCAGGTTCTTGTAGTCCA | 58.5 | |

| hsp90a.1 | Forward | GGAGTTCGACGGTAAGAGCC | 58.8 |

| Reverse | AGTCTGTTGGACACCGTCAC | 54.8 | |

| hsp70 | Forward | CGCCCTGGAGTCGTATGCTTTC | 65.8 |

| Reverse | GCCAGCCGATGACCTCGTTGC | 69.4 | |

| slc25a25a | Forward | TGCTGAAAACTCGTCTCGCT | 58.5 |

| Reverse | CATGTTGGGGACGTAGCCTT | 59.8 | |

| DNAJB6 | Forward | TTACGGGGGCTTTGTTGGTT | 61.9 |

| Reverse | GGAGAAAGAGGTGAAGCCCC | 60.1 | |

| CYP7A1 | Forward | GGGCAGTAGTGGTGGGATTC | 59.0 |

| Reverse | TGCCCATACTTCTTCTGCCG | 61.1 | |

| GNRHR2 | Forward | GCTGGGGCTGCTTCTATGTG | 60.6 |

| Reverse | CTGAAAGAGTCCAGCTCCCTC | 58.1 | |

| NPR2 | Forward | GTGTGGTGGACAGTCGATTTG | 58.3 |

| Reverse | TGGAGAACTTGCATAGAGTGCG | 60.6 | |

| CASP6 | Forward | ATCGGGGTTGTCTTGTCGAA | 60.1 |

| Reverse | GCTGCATTTCCCAGCACTTC | 60.6 | |

| GCK | Forward | TTTTGGTCGCGTTGAGTTCTG | 61.3 |

| Reverse | CGGCGCAGTTAGACGAGAAA | 61.5 | |

| GAPDH | Forward | AGTCCGTCTGGAGAAACCC | 57.0 |

| Reverse | CAAAGATGGAGGAGTGAGTGT | 54.1 |

| Group | Sample | Clean Data (bp) | Clean Reads (Mb) | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) | GC Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL | CTL-1 | 6,475,702,062 | 43.853940 | 98.36% | 94.89% | 55.15% |

| CTL-2 | 7,099,878,863 | 48.167156 | 98.37% | 94.98% | 54.07% | |

| CTL-3 | 7,358,091,696 | 49.814014 | 98.44% | 95.12% | 53.93% | |

| TA | TA-1 | 6,361,078,072 | 43.014726 | 98.41% | 95.03% | 53.96% |

| TA-2 | 7,105,868,744 | 48.142580 | 98.38% | 95.00% | 53.68% | |

| TA-3 | 7,545,678,321 | 51.070376 | 98.45% | 95.16% | 53.28% | |

| TB | TB-1 | 7,910,701,740 | 53.563198 | 98.29% | 94.68% | 56.63% |

| TB-2 | 7,118,001,549 | 48.180086 | 98.36% | 94.91% | 54.20% | |

| TB-3 | 7,705,624,944 | 52.164258 | 98.37% | 94.93% | 54.32% | |

| TC | TC-1 | 6,901,596,551 | 46.778486 | 98.31% | 94.75% | 56.07% |

| TC-2 | 6,732,537,497 | 45.604702 | 98.30% | 94.76% | 54.71% | |

| TC-3 | 7,515,726,757 | 50.878070 | 98.35% | 94.88% | 54.19% |

| ID | Symbol | Log2 (FC) | p Value | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMAX5B002285 | RBP7 | 13.39026 | 8.46 × 10−9 | up |

| SMAX5B008965 | HHIPL2 | 12.17374 | 4.64 × 10−9 | up |

| SMAX5B006145 | MYOC | 12.09452 | 3.35 × 10−15 | up |

| SMAX5B021851 | CRYGNB | 11.8778 | 4.13 × 10−11 | up |

| SMAX5B018082 | NEFM | 11.5134 | 2.53 × 10−7 | up |

| SMAX5B007292 | EPD | −16.70846 | 1.83 × 10−9 | down |

| SMAX5B012667 | FBLN7 | −15.29945 | 6.85 × 10−30 | down |

| SMAX5B018368 | RDH7 | −15.01527 | 7.17 × 10−51 | down |

| SMAX5B015453 | CYB5R2 | −14.81061 | 5.02 × 10−34 | down |

| SMAX5B008939 | FAM213B | −14.77297 | 1.58 × 10−50 | down |

| ID | Symbol | Log2 (FC) | p Value | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMAX5B018187 | gcg2 | 14.85200924 | 2.62 × 10−5 | up |

| SMAX5B012775 | hsp30 | 11.63026713 | 3.80 × 10−6 | up |

| SMAX5B022597 | dio1 | 10.86108691 | 9.79 × 10−5 | up |

| SMAX5B010135 | set-1 | 10.43045255 | 3.76 × 10−7 | up |

| SMAX5B011509 | LRAT | 10.38801729 | 4.48 × 10−5 | up |

| SMAX5B002496 | ENDOD1 | −10.81645038 | 7.52 × 10−8 | down |

| SMAX5B020931 | Tmem235 | −10.79495732 | 3.01 × 10−5 | down |

| SMAX5B012680 | Cenpq | −10.6911619 | 7.00 × 10−6 | down |

| XLOC_024262 | Vcam1 | −10.55074679 | 0.000306632 | down |

| SMAX5B022022 | Irs2 | −10.51175265 | 0.000106176 | down |

| ID | Symbol | Log2 (FC) | p Value | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMAX5B018187 | gcg2 | 18.60534 | 2.47 × 10−9 | up |

| SMAX5B017929 | Pcsk2 | 11.18818 | 1.57 × 10−6 | up |

| SMAX5B000021 | SCG5 | 11.14636 | 3.14 × 10−6 | up |

| SMAX5B011417 | baiap2l2 | 10.99906 | 4.59 × 10−9 | up |

| SMAX5B010135 | set-1 | 10.5216 | 1.60 × 10−6 | up |

| SMAX5B020931 | Tmem235 | −10.79495732 | 5.25 × 10−5 | down |

| SMAX5B022022 | Irs2 | −10.51175265 | 0.000232012 | down |

| SMAX5B009464 | tuba | −10.22480563 | 0.000216174 | down |

| XLOC_008456 | Myl7 | −9.936637939 | 0.000533848 | down |

| SMAX5B019138 | Msn | −9.631783357 | 0.000131621 | down |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Gao, T.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Y. Elucidating the Molecular Basis of Thermal Stress Response in Juvenile Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) via an Integrative Transcriptome–Metabolome Approach. Biology 2025, 14, 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101413

Chen X, Gao T, Wang Z, Chen S, Zhang N, Zhang X, Jia Y. Elucidating the Molecular Basis of Thermal Stress Response in Juvenile Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) via an Integrative Transcriptome–Metabolome Approach. Biology. 2025; 14(10):1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101413

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiatian, Tao Gao, Ziwen Wang, Shuaiyu Chen, Nan Zhang, Xiaoming Zhang, and Yudong Jia. 2025. "Elucidating the Molecular Basis of Thermal Stress Response in Juvenile Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) via an Integrative Transcriptome–Metabolome Approach" Biology 14, no. 10: 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101413

APA StyleChen, X., Gao, T., Wang, Z., Chen, S., Zhang, N., Zhang, X., & Jia, Y. (2025). Elucidating the Molecular Basis of Thermal Stress Response in Juvenile Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) via an Integrative Transcriptome–Metabolome Approach. Biology, 14(10), 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101413