From Bench to Brain: Translating EV and Nanocarrier Research into Parkinson’s Disease Therapies

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

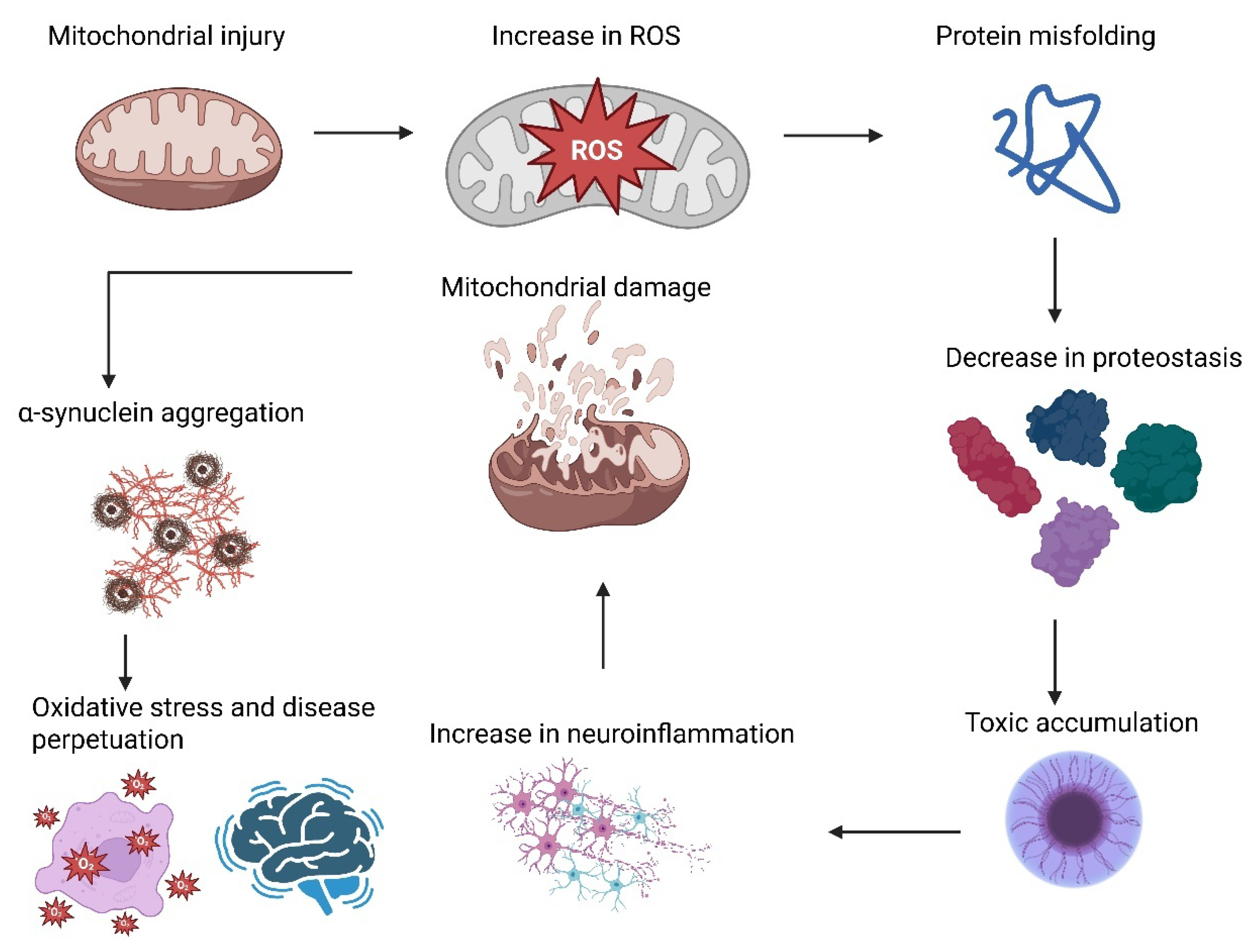

2. PD Pathogenesis

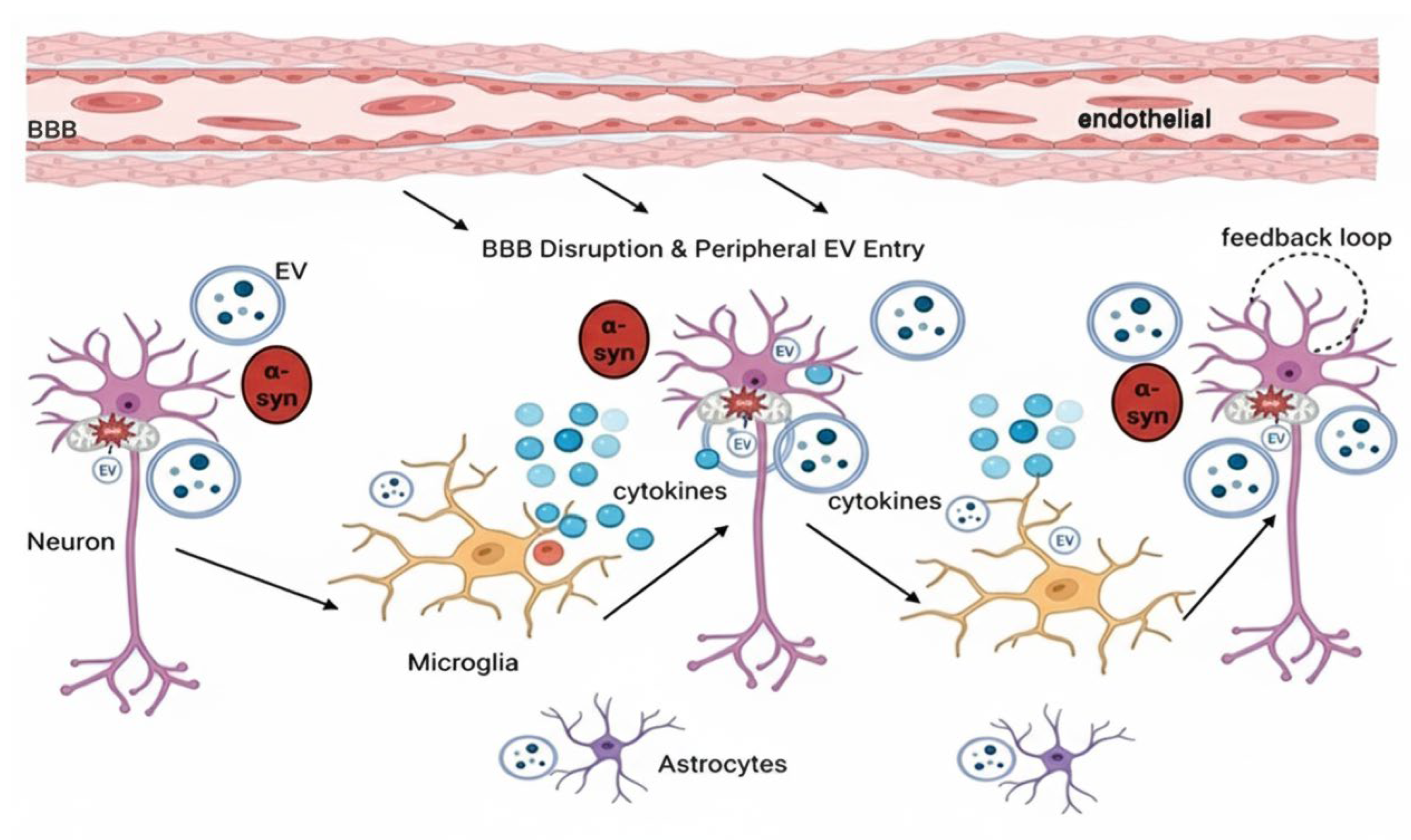

3. The Involvement of EV in PD Pathogenesis

4. Therapeutic Mechanisms of MSC-EVs in PD

5. EVs from Non-MSC in PD Therapy

6. Clinical Trial of EVs for PD

7. Unresolved Mechanisms of EVs in PD

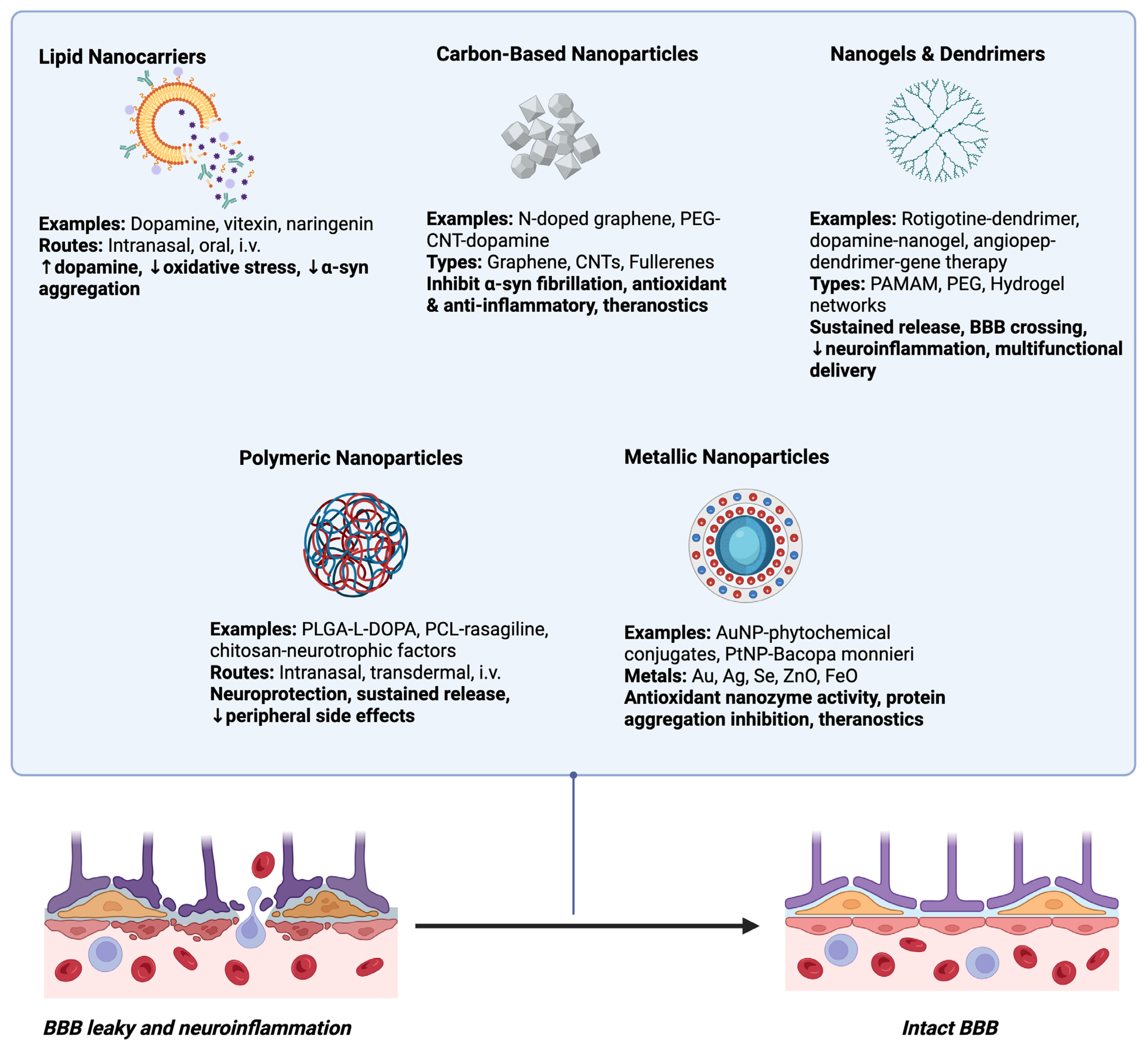

8. Emerging Nanocarrier Systems for PD Therapy

8.1. Lipid Nanocarriers

8.2. Polymeric Nanoparticles

8.3. Metallic Nanoparticles

8.4. Carbon-Based Nanoparticles

8.5. Nanogels and Dendrimers

9. EVs Versus Synthetic Nanocarriers in PD Treatment

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tinazzi, M.; Gandolfi, M.; Artusi, C.A.; Bannister, K.; Rukavina, K.; Brefel-Courbon, C.; de Andrade, D.C.; Perez-Lloret, S.; Mylius, V. Advances in diagnosis, classification, and management of pain in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2025, 24, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmeier, D.J. Determinants of dopaminergic neuron loss in Parkinson’s disease. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 3657–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peña-Zelayeta, L.; Delgado-Minjares, K.M.; Villegas-Rojas, M.M.; León-Arcia, K.; Santiago-Balmaseda, A.; Andrade-Guerrero, J.; Pérez-Segura, I.; Ortega-Robles, E.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; Arias-Carrión, O. Redefining Non-Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pu, J. Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease: From Pathogenetic Dysfunction to Potential Clinical Application. Park. Dis. 2016, 2016, 1720621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Muleiro Alvarez, M.; Cano-Herrera, G.; Osorio Martínez, M.F.; Vega Gonzales-Portillo, J.; Monroy, G.R.; Murguiondo Pérez, R.; Torres-Ríos, J.A.; van Tienhoven, X.A.; Garibaldi Bernot, E.M.; Esparza Salazar, F.; et al. A Comprehensive Approach to Parkinson’s Disease: Addressing Its Molecular, Clinical, and Therapeutic Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhidayasiri, R.; Sringean, J.; Phumphid, S.; Anan, C.; Thanawattano, C.; Deoisres, S.; Panyakaew, P.; Phokaewvarangkul, O.; Maytharakcheep, S.; Buranasrikul, V.; et al. The rise of Parkinson’s disease is a global challenge, but efforts to tackle this must begin at a national level: A protocol for national digital screening and “eat, move, sleep” lifestyle interventions to prevent or slow the rise of non-communicable diseases in Thailand. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1386608. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Qiao, L.; Li, M.; Wen, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, X. Global, regional, national epidemiology and trends of Parkinson’s disease from 1990 to 2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 16, 1498756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, A.; Simcox, E.; Turnbull, D. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: Why is advancing age the biggest risk factor? Ageing Res Rev. 2014, 14, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pereira, G.M.; Teixeira-Dos-Santos, D.; Soares, N.M.; Marconi, G.A.; Friedrich, D.C.; Awad, P.S.; Santos-Lobato, B.L.; Brandão, P.R.P.; Noyce, A.J.; Marras, C.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in lower to upper-middle-income countries. npj Park. Dis. 2024, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, A.W.; Roberts, E.; Beck, J.C.; Fiske, B.; Ross, W.; Savica, R.; Eeden, S.K.V.D.; Tanner, C.M.; Marras, C.; Alcalay, R.; et al. Incidence of Parkinson disease in North America. npj Park. Dis. 2022, 8, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabresi, P.; Mechelli, A.; Natale, G.; Volpicelli-Daley, L.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Ghiglieri, V. Alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies: From overt neurodegeneration back to early synaptic dysfunction. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battis, K.; Xiang, W.; Winkler, J. The Bidirectional Interplay of α-Synuclein with Lipids in the Central Nervous System and Its Implications for the Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saramowicz, K.; Siwecka, N.; Galita, G.; Kucharska-Lusina, A.; Rozpędek-Kamińska, W.; Majsterek, I. Alpha-Synuclein Contribution to Neuronal and Glial Damage in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, T.; Steiner, J.A.; Brundin, P. Sorting out release, uptake and processing of alpha-synuclein during prion-like spread of pathology. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139 (Suppl. 1), 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Kong, X.; Qiao, J.; Wei, J. Decoding Parkinson’s Disease: The interplay of cell death pathways, oxidative stress, and therapeutic innovations. Redox Biol. 2025, 85, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hu, W.; Jin, W.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, H.; Li, J.; Lin, Z.; Lin, W. Role of iron in brain development, aging, and neurodegenerative diseases. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2472871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, C.; Piao, M.; Liu, M. Oxidative cell death in the central nervous system: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1562344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Yang, M.; Jiang, N.; Luo, S.; Sun, L. Acyl-CoA synthase ACSL4: An essential target in ferroptosis and fatty acid metabolism. Chin. Med. J. 2023, 136, 2521–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotla, N.K.; Dutta, P.; Parimi, S.; Das, N.K. The Role of Ferritin in Health and Disease: Recent Advances and Understandings. Metabolites 2022, 12, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Cai, J.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Q. Iron Deposition in Parkinson’s Disease: A Mini-Review. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 44, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakye, G.F.; Paoliello, M.M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Bowman, A.B.; Aschner, M. Manganese-Induced Parkinsonism and Parkinson’s Disease: Shared and Distinguishable Features. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 7519–7540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyatha, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, D.; Kim, K. Association between Heavy Metal Exposure and Parkinson’s Disease: A Review of the Mechanisms Related to Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaei, M.; Koushki, K.; Taebi, K.; Yousefi Taba, M.; Keshavarz Hedayati, S.; Keshavarz Shahbaz, S. Metal nanoparticles in neuroinflammation: Impact on microglial dynamics and CNS function. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 5426–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.Q.; Jv, X.H.; Ma, X.Z.; Li, C.; Liu, L.; Jia, W.T.; Qu, L.; Chen, L.L.; Xie, J.X. Cell senescence induced by toxic interaction between α-synuclein and iron precedes nigral dopaminergic neuron loss in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2024, 45, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehay, B.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Caldwell, G.A.; Caldwell, K.A.; Yue, Z.; Cookson, M.R.; Klein, C.; Vila, M.; Bezard, E. Lysosomal impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2013, 28, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, F.; Meng, L.; Du, K.; Li, X. The autophagy-lysosome pathway: A potential target in the chemical and gene therapeutic strategies for Parkinson’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taymans, J.-M.; Fell, M.; Greenamyre, T.; Hirst, W.D.; Mamais, A.; Padmanabhan, S.; Peter, I.; Rideout, H.; Thaler, A. Perspective on the current state of the LRRK2 field. npj Park. Dis. 2023, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.H.; Han, S.J.; Son, I. The Multifaceted Role of LRRK2 in Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Q.; Ni, H.; Li, D.; Gao, R.; Chen, G. The Role of LRRK2 in Neurodegeneration of Parkinson Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granek, Z.; Barczuk, J.; Siwecka, N.; Rozpędek-Kamińska, W.; Kucharska, E.; Majsterek, I. GBA1 Gene Mutations in α-Synucleinopathies—Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Pathology and Their Clinical Significance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Schapira, A.H.V. GBA Variants and Parkinson Disease: Mechanisms and Treatments. Cells 2022, 11, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Liu, M.; Ke, W.; Chen, L.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Z. Lysosomal dysfunction in α-synuclein pathology: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2024, 81, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkovska, I.; Krainc, D.; Mazzulli, J.R. Molecular mechanisms of α-synuclein and GBA1 in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 373, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanz, J.; Saftig, P. Parkinson’s disease: Acid-glucocerebrosidase activity and alpha-synuclein clearance. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139 (Suppl. 1), 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, H.; Tang, B.; Guo, J. Clinical, mechanistic, biomarker, and therapeutic advances in GBA1-associated Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2024, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Blair, N.F.; Sue, C.M. The role of ATP13A2 in Parkinson’s disease: Clinical phenotypes and molecular mechanisms. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2015, 30, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehay, B.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Ramirez, A.; Perier, C.; Klein, C.; Vila, M.; Bezard, E. Lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson disease: ATP13A2 gets into the groove. Autophagy 2012, 8, 1389–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenovic, M.; Tresse, E.; Mazzulli, J.R.; Taylor, J.P.; Krainc, D. Deficiency of ATP13A2 leads to lysosomal dysfunction, α-synuclein accumulation, and neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 4240–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMahon Copas, A.N.; McComish, S.F.; Fletcher, J.M.; Caldwell, M.A. The Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s Disease: A Complex Interplay Between Astrocytes, Microglia, and T Lymphocytes? Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 666737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, M.; Connor-Robson, N.; Wade-Martins, R. LRRK2: Autophagy and Lysosomal Activity. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.; Cao, W.J.; Zhao, R.; Lu, M.; Hu, G.; Qiao, C. ATP13A2 protects dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease: From biology to pathology. J. Biomed. Res. 2022, 36, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.L.; Tan, J.M. Role of the ubiquitin proteasome system in Parkinson’s disease. BMC Biochem. 2007, 8 (Suppl. 1), S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, H. Ubiquitination-Proteasome System (UPS) and Autophagy Two Main Protein Degradation Machineries in Response to Cell Stress. Cells 2022, 11, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, M.; Du, X.; Jiao, Q.; Chen, X.; Jiang, H. Expanding the role of proteasome homeostasis in Parkinson’s disease: Beyond protein breakdown. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, B.; Galka, D.; Häffner, N.; Wang, D.; Schmitt, K.; Valerius, O.; Knop, M.; Braus, G.H. α-Synuclein Decreases the Abundance of Proteasome Subunits and Alters Ubiquitin Conjugates in Yeast. Cells 2021, 10, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, T.R.; Margolis, S.S. Mechanisms of ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation and their roles in age-related neurodegenerative disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 12, 1531797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittelmeier, J.; Nachman, E.; Nussbaum-Krammer, C. Molecular Chaperones: A Double-Edged Sword in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 581374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Benito, M.; Granado, N.; García-Sanz, P.; Michel, A.; Dumoulin, M.; Moratalla, R. Modeling Parkinson’s Disease With the Alpha-Synuclein Protein. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi-Fakhari, D.; Saidi, L.J.; Wahlster, L. Molecular chaperones and protein folding as therapeutic targets in Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2013, 1, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, E.; Tel, B.C.; Şahin, G. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease and its Treatment Opportunities. Balk. Med. J. 2022, 39, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, T.N.; Pant, D.B.; Eckhoff, E.A.; Gongaware, R.N.; Do, T.; Hutchison, D.F.; Gleixner, A.M.; Leak, R.K. Astrocytes Do Not Forfeit Their Neuroprotective Roles After Surviving Intense Oxidative Stress. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garretti, F.; Monahan, C.; Sette, A.; Agalliu, D.; Sulzer, D. T cells, α-synuclein and Parkinson disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2022, 184, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Y.; Carrasco, C.M.; Campos, J.D.; Aguirre, P.; Núñez, M.T. Parkinson’s Disease: The Mitochondria-Iron Link. Park. Dis. 2016, 2016, 7049108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AGonzález-Rodríguez, P.; Zampese, E.; Stout, K.A.; Guzman, J.N.; Ilijic, E.; Yang, B.; Tkatch, T.; Stavarache, M.A.; Wokosin, D.L.; Gao, L.; et al. Disruption of mitochondrial complex I induces progressive parkinsonism. Nature 2021, 599, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 55Coleman, C.; Martin, I. Unraveling Parkinson’s Disease Neurodegeneration: Does Aging Hold the Clues? J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, 2321–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risiglione, P.; Zinghirino, F.; Di Rosa, M.C.; Magrì, A.; Messina, A. Alpha-Synuclein and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease: The Emerging Role of VDAC. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.B.; Malireddi, A.; Abera, M.; Noor, K.; Ansar, M.; Boddeti, S.; Nath, T.S. Gut Microbiome and Its Role in Parkinson’s Disease. Cureus 2024, 16, e73150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Bargues-Carot, A.; Riaz, Z.; Wickham, H.; Zenitsky, G.; Jin, H.; Anantharam, V.; Kanthasamy, A.; Kanthasamy, A.G. Impact of Environmental Risk Factors on Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Neuroinflammation, Protein Misfolding, and Oxidative Stress in the Etiopathogenesis of Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. The Redox Revolution in Brain Medicine: Targeting Oxidative Stress with AI, Multi-Omics and Mitochondrial Therapies for the Precision Eradication of Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Q.; Wu, L.; Pang, D.; Jiang, P. Exosomes in brain diseases: Pathogenesis and therapeutic targets. MedComm 2023, 4, e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, M. Role of exosomes in the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of central nervous system diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Ho, M.S.; Zhang, S. Pathogenesis of α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease: From a Neuron-Glia Crosstalk Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuele, M.; Chieregatti, E. Mechanisms of alpha-synuclein action on neurotransmission: Cell-autonomous and non-cell autonomous role. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 865–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.Y.; Xie, X.X.; Liu, R.T. The Role of α-Synuclein Oligomers in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, E.; Chandrasekhar, G.; Chandrasekar, P.; Anbarasu, K.; Vickram, A.S.; Karunakaran, R.; Rajasekaran, R.; Srikumar, P.S. Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 736978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hossinger, A.; Göbbels, S.; Vorberg, I.M. Prions on the run: How extracellular vesicles serve as delivery vehicles for self-templating protein aggregates. Prion 2017, 11, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picca, A.; Guerra, F.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Bucci, C.; Marzetti, E. Circulating extracellular vesicles: Friends and foes in neurodegeneration. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistrelli, L.; Contaldi, E.; Comi, C. The Impact of SNCA Variations and Its Product Alpha-Synuclein on Non-Motor Features of Parkinson’s Disease. Life 2021, 11, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, H.B.; Kearney, B.; Bitan, G. A minute fraction of α-synuclein in extracellular vesicles may be a major contributor to α-synuclein spreading following autophagy inhibition. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 1001382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Verdera, H.; Gitz-Francois, J.J.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Vader, P. Cellular uptake of extracellular vesicles is mediated by clathrin-independent endocytosis and macropinocytosis. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2017, 266, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Ikezu, T. Emerging roles of extracellular vesicles in neurodegenerative disorders. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 130, 104512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Stewart, T.; Yang, D.; Thorland, E.; Soltys, D.; Aro, P.; Khrisat, T.; Xie, Z.; Li, N.; Liu, Z.; et al. Erythrocytic α-synuclein contained in microvesicles regulates astrocytic glutamate homeostasis: A new perspective on Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, S.; Yeman Kiyak, B.; Akbayir, R.; Seyhali, R.; Arpaci, T. Microglia Mediated Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Romero, A.; Montpeyó, M.; Martinez-Vicente, M. The Emerging Role of the Lysosome in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.J.; Lee, C.Y.; Menozzi, E.; Schapira, A.H.V. Genetic variations in GBA1 and LRRK2 genes: Biochemical and clinical consequences in Parkinson disease. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 971252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erb, M.L.; Moore, D.J. LRRK2 and the Endolysosomal System in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2020, 10, 1271–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, N.; Shaheen, A.; Osama, M.; Nashwan, A.J.; Bharmauria, V.; Flouty, O. MicroRNAs regulation in Parkinson’s disease, and their potential role as diagnostic and therapeutic targets. npj Park. Dis. 2024, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorite, P.; Domínguez, J.N.; Palomeque, T.; Torres, M.I. Extracellular Vesicles: Advanced Tools for Disease Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxakis, E. Post-transcriptional regulation of alpha-synuclein expression by mir-7 and mir-153. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 12726–12734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Florio, T.; Perez-Castro, C. Extracellular Vesicles Loaded miRNAs as Potential Modulators Shared Between Glioblastoma, and Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 590034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slota, J.A.; Booth, S.A. MicroRNAs in Neuroinflammation: Implications in Disease Pathogenesis, Biomarker Discovery and Therapeutic Applications. Non-Coding RNA 2019, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, N. The Emerging Role of Autophagy-Associated lncRNAs in the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.S.; Moglad, E.; Afzal, M.; Sharma, S.; Gupta, G.; Sivaprasad, G.V.; Deorari, M.; Almalki, W.H.; Kazmi, I.; Alzarea, S.I.; et al. Autophagy-associated non-coding RNAs: Unraveling their impact on Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Cui, L.; Zhong, W.; Cai, Y. Autophagy-Associated lncRNAs: Promising Targets for Neurological Disease Diagnosis and Therapy. Neural Plast. 2020, 2020, 8881687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Conde, L.D.; Ramos-Acevedo, R.; Reyes-Hernández, M.A.; Balbuena-Olvera, A.J.; Morales-Moreno, I.D.; Argüero-Sánchez, R.; Schüle, B.; Guerra-Crespo, M. Alpha-Synuclein Physiology and Pathology: A Perspective on Cellular Structures and Organelles. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Pastor, A. Extracellular Vesicles as Mediators of Neuroinflammation in Intercellular and Inter-Organ Crosstalk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Chowdhury, S.; Ledeen, R. Alpha-Synuclein and GM1 Ganglioside Co-Localize in Neuronal Cytosol Leading to Inverse Interaction-Relevance to Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.; Lee, S.B.; Lee, H.S.; Yang, H.O.; Park, J.; Kim, J.S.; Oh, E.; Park, S.; Jang, W. Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of Autophagy-related Proteins Represent Potentially Novel Biomarkers of Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 16866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kang, J.H.; Irwin, D.J.; Chen-Plotkin, A.S.; Siderowf, A.; Caspell, C.; Coffey, C.S.; Waligórska, T.; Taylor, P.; Pan, S.; Frasier, M.; et al. Association of cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 1-42, T-tau, P-tau181, and α-synuclein levels with clinical features of drug-naive patients with early Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013, 70, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, J.; Ou, R.; Li, C.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Q.; Pang, D.; Liu, K.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, T.; et al. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein as a biomarker of disease progression in Parkinson’s disease: A prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, U.; Singh, S.; Pal, S.; Prasad, S.; Agrawal, B.K.; Saini, R.V.; Chakrabarti, S. Alpha-Synuclein as a Biomarker of Parkinson’s Disease: Good, but Not Good Enough. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 702639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Yu, C.Q.; Xue, M.; Hu, P.P. Early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease: Biomarker study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1495769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karami, M.; Sanaye, P.M.; Ghorbani, A.; Amirian, R.; Goleij, P.; Babamohamadi, M.; Izadi, Z. Recent advances in targeting LRRK2 for Parkinson’s disease treatment. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zarkali, A.; Thomas, G.E.C.; Zetterberg, H.; Weil, R.S. Neuroimaging and fluid biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease in an era of targeted interventions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cao, D.; Yue, J.; Wei, Z.; Huang, D.H.; Sun, X.; Liu, K.X.; Wang, P.; Jiang, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. Magnetic resonance imaging of brain structural and functional changes in cognitive impairment associated with Parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1494385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Du, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, W.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J. Biomarkers and the Role of α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 645996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, Q.; Kuang, G.; Liu, L.; Yu, D.; Lin, Z.; Xiong, N. Brain-derived extracellular vesicles: A promising avenue for Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Neural Regen. Res. 2026, 21, 1447–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Turano, E.; Scambi, I.; Virla, F.; Bonetti, B.; Mariotti, R. Extracellular Vesicles from Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Towards Novel Therapeutic Strategies for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y. Living Cells and Cell-Derived Vesicles: A Trojan Horse Technique for Brain Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaković, J.; Šerer, K.; Barišić, B.; Mitrečić, D. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for neurological disorders: The light or the dark side of the force? Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1139359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, H.; Mikhailova, M.V.; Mardasi, M.; Jafarzadehgharehziaaddin, M.; Shahrokh, S.; Thangavelu, L.; Ahmadi, H.; Shomali, N.; Yaghoubi, Y.; Zamani, M.; et al. Emerging role of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs)-derived exosome in neurodegeneration-associated conditions: A groundbreaking cell-free approach. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogna, T.; Housden, B.E.; Houldsworth, A. Exploring the Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease and the Efficacy of Antioxidant Treatment. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bej, E.; Cesare, P.; Volpe, A.R.; d’Angelo, M.; Castelli, V. Oxidative Stress and Neurodegeneration: Insights and Therapeutic Strategies for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurol. Int. 2024, 16, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Munteanu, O.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Enyedi, M.; Ciurea, A.V.; Tataru, C.P. From Synaptic Plasticity to Neurodegeneration: BDNF as a Transformative Target in Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-Y.; Gao, Y.-M.; Feng, T.; Rao, J.-S.; Zhao, C. Enhancing Functional Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury Through Neuroplasticity: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, A.; Zheng, X. m6A RNA methylation in brain injury and neurodegenerative disease. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 995747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, J.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, R.; Hu, W. P38 Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase and Parkinson’s Disease. Transl. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chiu, C.C.; Yeh, T.H.; Chen, R.S.; Chen, H.C.; Huang, Y.Z.; Weng, Y.H.; Cheng, Y.C.; Liu, Y.C.; Cheng, A.J.; Lu, Y.C.; et al. Upregulated Expression of MicroRNA-204-5p Leads to the Death of Dopaminergic Cells by Targeting DYRK1A-Mediated Apoptotic Signaling Cascade. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng, D.; Chen, J. MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s disease: From pathogenesis to diagnostics and therapeutic strategies. Neuroscience 2025, 568, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Abouelnazar, F.A.; Iqbal, M.A.; Pan, J.; Zheng, X.; Chen, T.; Shen, W.; Yin, J.; Yan, Y.; Liu, P.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as a plausible immunomodulatory therapeutic tool for inflammatory diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1563427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, F.; Fusco, S.; Grassi, C. Dual role of brain-derived extracellular vesicles in dementia-related neurodegenerative disorders: Cargo of disease spreading signals and diagnostic-therapeutic molecules. Transl. Neurodegener. 2022, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Pearse, D.D. The Yin and Yang of Microglia-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in CNS Injury and Diseases. Cells 2024, 13, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picca, A.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Landi, F.; Bernabei, R.; Marzetti, E. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Neuroinflammation: Intertwined Roads to Neurodegeneration. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Lan, G.; Xu, B.; Yu, Z.; Tian, C.; Lei, X.; Meissner, W.G.; Feng, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. α-Synuclein-carrying astrocytic extracellular vesicles in Parkinson pathogenesis and diagnosis. Transl. Neurodegener. 2023, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- d’Angelo, M.; Cimini, A.; Castelli, V. Insights into the Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Secretome in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volarevic, A.; Harrell, C.R.; Arsenijevic, A.; Djonov, V.; Volarevic, V. Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2025, 14, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, D.; Pan, R.; Sun, Y.; He, X.; Qiu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wu, X.; Xi, X.; Hu, R.; et al. Neural stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles: A new therapy approach in neurological diseases. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1548206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, X.; Zheng, J.C. Neural stem/progenitor cell-derived extracellular vesicles: A novel therapy for neurological diseases and beyond. MedComm 2023, 4, e214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vogel, A.D.; Upadhya, R.; Shetty, A.K. Neural stem cell derived extracellular vesicles: Attributes and prospects for treating neurodegenerative disorders. EBioMedicine 2018, 38, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moretti, E.H.; Lin, A.L.Y.; Peruzzotti-Jametti, L.; Pluchino, S.; Mozafari, S. Neural Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Advanced Neural Repair. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sil, S.; Dagur, R.S.; Liao, K.; Peeples, E.S.; Hu, G.; Periyasamy, P.; Buch, S. Strategies for the use of Extracellular Vesicles for the Delivery of Therapeutics. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020, 15, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anoop, M.; Datta, I. Stem Cells Derived from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHED) in Neuronal Disorders: A Review. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 16, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Shi, S.; Wang, S. Stem cells from human-exfoliated deciduous teeth can differentiate into dopaminergic neuron-like cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2010, 19, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naderi, F.; Mehdiabadi, M.; Kamarehei, F. The therapeutic effects of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth on clinical diseases: A narrative review study. Am. J. Stem Cells 2022, 11, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hering, C.; Shetty, A.K. Extracellular Vesicles Derived From Neural Stem Cells, Astrocytes, and Microglia as Therapeutics for Easing TBI-Induced Brain Dysfunction. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2023, 12, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, Y.R.; Wong, C.C.; Chen, Y.N.; Yang, B.H.; Lee, P.H.; Shiau, C.Y.; Wang, K.C.; Li, C.H. Factors derived from human exfoliated deciduous teeth stem cells reverse neurological deficits in a zebrafish model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 2035–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narbute, K.; Piļipenko, V.; Pupure, J.; Dzirkale, Z.; Jonavičė, U.; Tunaitis, V.; Kriaučiūnaitė, K.; Jarmalavičiūtė, A.; Jansone, B.; Kluša, V.; et al. Intranasal Administration of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Human Teeth Stem Cells Improves Motor Symptoms and Normalizes Tyrosine Hydroxylase Expression in the Substantia Nigra and Striatum of the 6-Hydroxydopamine-Treated Rats. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2019, 8, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Tan, X.; Li, S.; Al-Nusaif, M.; Le, W. Role of Glia-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 765395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhya, R.; Zingg, W.; Shetty, S.; Shetty, A.K. Astrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles: Neuroreparative properties and role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2020, 323, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Markovic, M.; Olson, K.E.; Gendelman, H.E.; Mosley, R.L. Therapeutic Strategies for Immune Transformation in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, S201–S222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Y.L.; Kao, H.K.; Liu, Y.Y.; Loh, C.Y.Y. Engineered extracellular vesicles derived from pluripotent stem cells: A cell-free approach to regenerative medicine. Burn. Trauma 2025, 13, tkaf013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, X.; Dong, Y.; Gao, P.; Zhao, X.; Wang, M.; Wu, X.; Shen, J.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Z.; et al. Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in the therapeutic intervention of Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and stroke. Theranostics 2024, 14, 3358–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Guo, S.; Ren, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, S.; Yao, X. Current Strategies for Exosome Cargo Loading and Targeting Delivery. Cells 2023, 12, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putthanbut, N.; Lee, J.Y.; Borlongan, C.V. Extracellular vesicle therapy in neurological disorders. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 31, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, J.; Ouyang, K.; Ling, M.; Luo, J.; Sun, J.; Xi, Q.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Y. Extracellular vesicles: From large-scale production and engineering to clinical applications. J. Tissue Eng. 2025, 16, 20417314251319474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukerjee, N.; Bhattacharya, A.; Maitra, S.; Kaur, M.; Ganesan, S.; Mishra, S.; Ashraf, A.; Rizwan, M.; Kesari, K.K.; Tabish, T.A.; et al. Exosome isolation and characterization for advanced diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Mater. Today Bio. 2025, 31, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari-Gharalari, N.; Ghahremani-Nasab, M.; Naderi, R.; Chodari, L.; Nezhadshahmohammad, F. The potential of exosomal biomarkers: Revolutionizing Parkinson’s disease: How do they influence pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapeutic strategies? AIMS Neurosci. 2024, 11, 374–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vaz, M.; Soares Martins, T.; Henriques, A.G. Extracellular vesicles in the study of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: Methodologies applied from cells to biofluids. J. Neurochem. 2022, 163, 266–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heris, R.M.; Shirvaliloo, M.; Abbaspour-Aghdam, S.; Hazrati, A.; Shariati, A.; Youshanlouei, H.R.; Niaragh, F.J.; Valizadeh, H.; Ahmadi, M. The potential use of mesenchymal stem cells and their exosomes in Parkinson’s disease treatment. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aafreen, S.; Feng, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, G. Theranostic extracellular vesicles: A concise review of current imaging technologies and labeling strategies. Extracell. Vesicles Circ. Nucleic Acids 2023, 4, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Díaz Reyes, M.; Gatti, S.; Delgado Ocaña, S.; Ortega, H.H.; Banchio, C. Neuroprotective effect of NSCs-derived extracellular vesicles in Parkinson’s disease models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Sadida, H.Q.; Marzooqi, S.A.; Jerobin, J.; Altemani, F.H.; Algehainy, N.; Alanazi, M.A.; Abou-Samra, A.B.; Kumar, R.; et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ciferri, M.C.; Quarto, R.; Tasso, R. Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Tools: From Pre-Clinical to Clinical Applications. Biology 2021, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.C.; Chan, L.; Chen, J.H.; Hung, Y.C.; Hong, C.T. Plasma Extracellular Vesicle α-Synuclein Level in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Tian, C.; Xiong, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. Extracellular vesicles: New horizons in neurodegeneration. EBioMedicine 2025, 113, 105605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, G.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Feng, T. α-Synuclein in salivary extracellular vesicles as a potential biomarker of Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 696, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.K.; Chen, M.; Goldston, L.L.; Lee, K.-B. Extracellular vesicles as nanotheranostic platforms for targeted neurological disorder interventions. Nano Converg. 2024, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, D.; Bloem, B.R.; Kalia, L.V.; Postuma, R.B. Introduction: The Earliest Phase of Parkinson’s Disease: Possibilities for Detection and Intervention. J. Park. Dis. 2024, 14, S253–S255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualerzi, A.; Picciolini, S.; Bedoni, M.; Guerini, F.R.; Clerici, M.; Agliardi, C. Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers for Parkinson’s Disease: How Far from Clinical Translation? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacchi, E.; Burrello, J.; Burrello, A.; Bolis, S.; Monticone, S.; Barile, L.; Kaelin-Lang, A.; Melli, G. Profiling Inflammatory Extracellular Vesicles in Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid: An Optimized Diagnostic Model for Parkinson’s Disease. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Le, W. Biomarkers for Parkinson’s Disease: How Good Are They? Neurosci. Bull. 2020, 36, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, M.; Zhao, M.; Hu, D.; Xie, F.; Jin, Q.; Xiao, D.; Peng, Z.; Qin, T.; et al. Research progress of extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1496304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, S.R.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.L.; Wu, N.; Ye, J.S. Effectiveness of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles therapy for Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of preclinical studies. World J. Stem Cells 2025, 17, 102421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Hao, Z.; Yin, H.; Min, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, S.; Ruan, G. Engineered Extracellular Vesicles as a New Class of Nanomedicine. Chem Bio Eng. 2025, 2, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Li, X.D.; Zhang, S.M.; Wang, H.W.; Wang, Y.L. Extracellular vesicles in neurodegenerative diseases: Insights and new perspectives. Genes Dis. 2019, 8, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.-M.; Andreu, Z.; Bedina Zavec, A.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2015, 4, 27066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Du, S.; Guan, Y.; Xie, A.; Yan, Z.; Gao, S.; Li, W.; Rao, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, T. Extracellular vesicles: A rising star for therapeutics and drug delivery. J. Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Iqbal, Z.; Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Duan, L.; Xia, J. Cell-derived nanovesicle-mediated drug delivery to the brain: Principles and strategies for vesicle engineering. Mol Ther. 2023, 31, 1207–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Putri, P.H.L.; Alamudi, S.H.; Dong, X.; Fu, Y. Extracellular vesicles in age-related diseases: Disease pathogenesis, intervention, and biomarker. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crescitelli, R.; Falcon-Perez, J.; Hendrix, A.; Lenassi, M.; Minh, L.T.N.; Ochiya, T.; Noren Hooten, N.; Sandau, U.; Théry, C.; Nieuwland, R. Reproducibility of extracellular vesicle research. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2025, 14, e70036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reed, S.L.; Escayg, A. Extracellular vesicles in the treatment of neurological disorders. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 157, 105445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaur, M.; Fusco, S.; Van den Broek, B.; Aseervatham, J.; Rostami, A.; Iacovitti, L.; Grassi, C.; Lukomska, B.; Srivastava, A.K. Most recent advances and applications of extracellular vesicles in tackling neurological challenges. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 1923–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, B.; Gong, H.; Zhang, K.; Lin, Y.; Sun, M. Extracellular vesicles: Biological mechanisms and emerging therapeutic opportunities in neurodegenerative diseases. Transl. Neurodegener. 2024, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Russell, A.E.; Sneider, A.; Witwer, K.W.; Bergese, P.; Bhattacharyya, S.N.; Cocks, A.; Cocucci, E.; Erdbrügger, U.; Falcon-Perez, J.M.; Freeman, D.W.; et al. Biological membranes in EV biogenesis, stability, uptake, and cargo transfer: An ISEV position paper arising from the ISEV membranes and EVs workshop. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2019, 8, 1684862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leggio, L.; Paternò, G.; Vivarelli, S.; Falzone, G.G.; Giachino, C.; Marchetti, B.; Iraci, N. Extracellular Vesicles as Novel Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers for Parkinson’s Disease. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 1494–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, F.J.; Balaj, L.; Boulanger, C.M.; Carter, D.R.F.; Compeer, E.B.; D’Angelo, G.; El Andaloussi, S.; Goetz, J.G.; Gross, J.C.; Hyenne, V.; et al. The power of imaging to understand extracellular vesicle biology in vivo. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chuo, S.T.Y.; Chien, J.C.Y.; Lai, C.P.K. Imaging extracellular vesicles: Current and emerging methods. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 25, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandham, S.; Su, X.; Wood, J.; Nocera, A.L.; Alli, S.C.; Milane, L.; Zimmerman, A.; Amiji, M.; Ivanov, A.R. Technologies and Standardization in Research on Extracellular Vesicles. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1066–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, D.; Panda, P.K.; Ghosh, N.S. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Particles: A Comparative Review on Lipid-Based Nanocarriers. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemiyeh, P.; Mohammadi-Samani, S. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers as novel drug delivery systems: Applications, advantages and disadvantages. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 13, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrache, S.; Pathak, R.K.; Darley, K.L.; Choi, J.H.; Zaver, D.; Kolishetti, N.; Dhar, S. Nanocarriers for tracking and treating diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 3500–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Liu, D.; Xue, W.W.; Ma, L.; Xie, H.T.; Ning, K. Lipid-based nanoparticles for drug delivery in Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 20220359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, M.I.; Lopes, C.M.; Amaral, M.H.; Costa, P.C. Current insights on lipid nanocarrier-assisted drug delivery in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 149, 192–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirgadwar, S.M.; Kumar, R.; Preeti, K.; Khatri, D.K.; Singh, S.B. Neuroprotective Effect of Phloretin in Rotenone-Induced Mice Model of Parkinson’s Disease: Modulating mTOR-NRF2-p62 Mediated Autophagy-Oxidative Stress Crosstalk. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2023, 94, S109–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, S.D.; Ramesh, S.H.; Radhakrishna, G.K.; Sireesha, G.; Ramesh, S.; Kumar, B.S.; Hosur Dinesh, B.G.; Ganjipete, S.; Nagaraj, S.; Theivendren, P.; et al. Development and evaluation of S-carboxymethyl-L-cystine-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for Parkinson’s disease in murine and zebrafish models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallamaci, R.; Musarò, D.; Greco, M.; Caponio, A.; Castellani, S.; Munir, A.; Guerra, L.; Damato, M.; Fracchiolla, G.; Coppola, C.; et al. Dopamine- and Grape-Seed-Extract-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles: Interaction Studies between Particles and Differentiated SH-SY5Y Neuronal Cell Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Molecules 2024, 29, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Martínez, E.; Morales Hernández, M.E.; Castillo-González, J.; González-Rey, E.; Ruiz Martínez, M.A. Dopamine-loaded chitosan-coated solid lipid nanoparticles as a promise nanocarriers to the CNS. Neuropharmacology 2024, 249, 109871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudhipala, N.; Gorre, T. Neuroprotective Effect of Ropinirole Lipid Nanoparticles Enriched Hydrogel for Parkinson’s Disease: In Vitro, Ex Vivo, Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Evaluation. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Anand, S.; Shah, K.; Chauhan, N.S.; Sethiya, N.K.; Singhal, M. Emerging Role of Plant-Based Bioactive Compounds as Therapeutics in Parkinson’s Disease. Molecules 2023, 28, 7588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabadu, D.; Agrawal, N. Naringin Exhibits Neuroprotection Against Rotenone-Induced Neurotoxicity in Experimental Rodents. Neuromolecular Med. 2020, 22, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinchen, Y.; Jing, T.; Jiaoqiong, G. Lipid-based nanoparticles via nose-to-brain delivery: A mini review. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1214450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maher, R.; Moreno-Borrallo, A.; Jindal, D.; Mai, B.T.; Ruiz-Hernandez, E.; Harkin, A. Intranasal Polymeric and Lipid-Based Nanocarriers for CNS Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nguyen, T.-T.-L.; Duong, V.-A. Advancements in Nanocarrier Systems for Nose-to-Brain Drug Delivery. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Ma, X.; Liu, S.; Zong, S.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. Application of Natural Products in Neurodegenerative Diseases by Intranasal Administration: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, Q.; Chen, X.; Yu, S.; Gong, G.; Shu, H. Research progress in brain-targeted nasal drug delivery. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 15, 1341295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Satapathy, M.K.; Yen, T.L.; Jan, J.S.; Tang, R.D.; Wang, J.Y.; Taliyan, R.; Yang, C.H. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs): An Advanced Drug Delivery System Targeting Brain through BBB. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koo, J.; Lim, C.; Oh, K.T. Recent Advances in Intranasal Administration for Brain-Targeting Delivery: A Comprehensive Review of Lipid-Based Nanoparticles and Stimuli-Responsive Gel Formulations. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2024, 19, 1767–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, M.; Xiang, C.; Niu, R.; He, X.; Luo, W.; Liu, W.; Gu, R. Liposomes as versatile agents for the management of traumatic and nontraumatic central nervous system disorders: Drug stability, targeting efficiency, and safety. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 1883–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsairat, H.; Khater, D.; Sayed, U.; Odeh, F.; Al Bawab, A.; Alshaer, W. Liposomes: Structure, composition, types, and clinical applications. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhairiyah, F.; de Lange, E.C.M. Understanding Drug Delivery to the Brain Using Liposome-Based Strategies: Studies that Provide Mechanistic Insights Are Essential. AAPS J. 2021, 23, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Ghosh, S. Liposome-Mediated Anti-Viral Drug Delivery Across Blood-Brain Barrier: Can Lipid Droplet Target Be Game Changers? Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 44, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunay, M.S.; Ozer, A.Y.; Chalon, S. Drug Delivery Systems for Imaging and Therapy of Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronel, R.; Palmer, C.; Bernabeu-Zornoza, A.; Monteagudo, M.; Rosca, A.; Zambrano, A.; Liste, I. Physiological effects of amyloid precursor protein and its derivatives on neural stem cell biology and signaling pathways involved. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.S.; Jung, H.J.; Oh, J.S.; Song, D.Y. Use of PEGylated Immunoliposomes to Deliver Dopamine Across the Blood-Brain Barrier in a Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2016, 22, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Khanal, S.; Lee, E.; Choi, J.; Bohara, G.; Rimal, N.; Choi, D.Y.; Park, S. Astaxanthin-loaded brain-permeable liposomes for Parkinson’s disease treatment via antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, Z.; You, Y.; Yi, H.; Liu, X.; Tong, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, J. Key Lipoprotein Receptor Targeted Echinacoside-Liposomes Effective Against Parkinson’s Disease in Mice Model. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 8463–8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Lin, Q.; He, S.; Wang, L.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. A brain targeting functionalized liposomes of the dopamine derivative N-3,4-bis(pivaloyloxy)-dopamine for treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2018, 277, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomitaka, A.; Takemura, Y.; Huang, Z.; Roy, U.; Nair, M. Magnetoliposomes in Controlled-Release Drug Delivery Systems. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 47, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliakbari, F.; Mohammad-Beigi, H.; Rezaei-Ghaleh, N.; Becker, S.; Esmatabad, F.D.; Seyedi, H.A.E.; Bardania, H.; Marvian, A.T.; Collingwood, J.F.; Christiansen, G.; et al. The potential of zwitterionic nanoliposomes against neurotoxic alpha-synuclein aggregates in Parkinson’s Disease. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 9174–9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, C.; Patrício, A.B.; Prata, J.M.; Nadhman, A.; Chintamaneni, P.K.; Fonte, P. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles vs. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: A Comparative Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekade, A.R.; Mittha, P.S.; Pisal, C.S. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for Nose to Brain Delivery Targeting CNS: Diversified Role of Liquid Lipids for Synergistic Action. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 12, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Liu, Y.; Ma, R.; Cheng, G.; Guan, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, T. Anti-Parkinsonian Therapy: Strategies for Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier and Nano-Biological Effects of Nanomaterials. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Sharma, S.; Deshmukh, R.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, R. Development and Characterization of Nasal Delivery of Selegiline Hydrochloride Loaded Nanolipid Carriers for the Management of Parkinson’s Disease. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, R.; Esposito, E.; Drechsler, M.; Pavoni, G.; Cacciatore, I.; Sguizzato, M.; Di Stefano, A. L-dopa co-drugs in nanostructured lipid carriers: A comparative study. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2017, 72, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lmowafy, M.; Al-Sanea, M.M. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) as drug delivery platform: Advances in formulation and delivery strategies. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondarenko, O.; Saarma, M. Neurotrophic Factors in Parkinson’s Disease: Clinical Trials, Open Challenges and Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery to the Brain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 682597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witika, B.A.; Poka, M.S.; Demana, P.H.; Matafwali, S.K.; Melamane, S.; Malungelo Khamanga, S.M.; Makoni, P.A. Lipid-Based Nanocarriers for Neurological Disorders: A Review of the State-of-the-Art and Therapeutic Success to Date. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janhom, P.; Dharmasaroja, P. Neuroprotective Effects of Alpha-Mangostin on MPP(+)-Induced Apoptotic Cell Death in Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells. J. Toxicol. 2015, 2015, 919058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Huang, S.; Peng, L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, G.; Liu, T.; Yan, F.; Peng, X. The Nasal-Brain Drug Delivery Route: Mechanisms and Applications to Central Nervous System Diseases. MedComm 2025, 6, e70213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Z.; Li, X.; Lu, C.T.; Lin, M.; Chen, L.J.; Xiang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Jin, R.R.; Jiang, X.; Shen, X.T.; et al. Gelatin nanostructured lipid carriers-mediated intranasal delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor enhances functional recovery in hemiparkinsonian rats. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2014, 10, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Sharma, A.; Jain, V. An Overview of Nanostructured Lipid Carriers and its Application in Drug Delivery through Different Routes. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 13, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begines, B.; Ortiz, T.; Pérez-Aranda, M.; Martínez, G.; Merinero, M.; Argüelles-Arias, F.; Alcudia, A. Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery: Recent Developments and Future Prospects. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asil, S.M.; Ahlawat, J.; Barroso, G.G.; Narayan, M. Nanomaterial based drug delivery systems for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 4109–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 20, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobos-Puc, L.E.; Rodríguez-Salazar, M.d.C.; Silva-Belmares, S.Y.; Aguayo-Morales, H. Nanoparticle-Based Strategies to Enhance Catecholaminergic Drug Delivery for Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Advances, Challenges, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Future Pharmacol. 2025, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, M.; Cristóvão, A.C.; Saraiva, T.; Rocha, S.M.; Baltazar, G.; Ferreira, L.; Bernardino, L. Retinoic acid-loaded polymeric nanoparticles induce neuroprotection in a mouse model for Parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Xiong, S.; Liu, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Tan, H.; Chen, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, Q.; et al. Polymeric Nanoparticles-Based Brain Delivery with Improved Therapeutic Efficacy of Ginkgolide B in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 10453–10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, S.S.; Gupta, A.; Choudhury, A.; Yadav, A.; Sinha, A.; Kirti, A.; Singh, D.; Kujawska, M.; Kaushik, N.K.; Ghosh, A.; et al. Biophysical translational paradigm of polymeric nanoparticle: Embarked advancement to brain tumor therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 179, 117372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.K.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Choudhary, N.; Nathiya, D.; Thakur, V.; Gupta, R.; Pramanik, S.; Kumar, P.; Gupta, N.; Patel, A. Recent advances in nanotechnology for Parkinson’s disease: Diagnosis, treatment, and future perspectives. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1535682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseem, R.S.; D’cRuz, A.; Shetty, S.; Hafsa; Vardhan, A.; Shenoy, R.S.; Marques, S.M.; Kumar, L.; Verma, R. Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems: A Focused Review of the Physical Methods of Permeation Enhancement. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2024, 14, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersh, A.M.; Alomari, S.; Tyler, B.M. Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier: Advances in Nanoparticle Technology for Drug Delivery in Neuro-Oncology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Fong, D.; Bannon, M.J.; Trudeau, L.E.; Gonzalez-Barrios, J.A.; Arango-Rodriguez, M.L.; Hernandez-Chan, N.G.; Reyes-Corona, D.; Armendáriz-Borunda, J.; Navarro-Quiroga, I. NTS-Polyplex: A potential nanocarrier for neurotrophic therapy of Parkinson’s disease. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2012, 8, 1052–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Martin, A.; Han, X.; Shirihai, O.S.; Grinstaff, M.W. Biodegradable PLGA nanoparticles restore lysosomal acidity and protect neural PC-12 cells against mitochondrial toxicity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 13910–13917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, A.; Gaubert, A.; Latxague, L.; Dehay, B. PLGA-Based Nanoparticles for Neuroprotective Drug Delivery in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradian, H.; Keshvari, H.; Fasehee, H.; Dinarvand, R.; Faghihi, S. Combining NT3-overexpressing MSCs and PLGA microcarriers for brain tissue engineering: A potential tool for treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2017, 76, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwar, N.; Bhandari, R.; Kuhad, A.; Sinha, V.R. Polycaprolactone-based neurotherapeutic delivery of rasagiline targeting behavioral and biochemical deficits in Parkinson’s disease. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lababidi, J.M.; Azzazy, H.M.E. Revamping Parkinson’s disease therapy using PLGA-based drug delivery systems. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanumanthappa, R.; Heggannavar, G.B.; Banakar, A.; Achari, D.D.; Karoshi, V.R.; Krushna, B.R.R.; Bepari, A.; Assiri, R.A.; Altamimi, H.N.; Nanjaiah, H.; et al. A Levodopa-Encapsulated Poly-ε-Caprolactone Nanocomposite Improves the Motor Symptoms and Neurochemical Changes in a Rotenone-Induced Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 19682–19696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheradmand, H.; Babaloo, H.; Vojgani, Y.; Mirzakhanlouei, S.; Bayat, N. PCL/gelatin scaffolds and beta-boswellic acid synergistically increase the efficiency of CGR8 stem cells differentiation into dopaminergic neuron: A new paradigm of Parkinson’s disease cell therapy. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2021, 109, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbay, A.; Mohtaram, N.K.; Willerth, S.M. Controlled release of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor from poly(ε-caprolactone) microspheres. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2014, 4, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, R.; Shi, G.; Huang, X.; Li, K.; Wang, R.; Cao, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, N.; Yan, J. Chitosan alleviates symptoms of Parkinson’s disease by reducing acetate levels, which decreases inflammation and promotes repair of the intestinal barrier and blood-brain barrier. Neural Regen. Res. 2026, 21, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardoiwala, M.N.; Karmakar, S.; Choudhury, S.R. Chitosan nanocarrier for FTY720 enhanced delivery retards Parkinson’s disease via PP2A-EzH2 signaling in vitro and ex vivo. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 254, 117435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramod Kumar, P.; Harish Prashanth, K.V. Diet with Low Molecular Weight Chitosan exerts neuromodulation in Rotenone induced Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruczkowska, W.; Gałęziewska, J.; Grabowska, K.H.; Gromek, P.; Czajkowska, K.; Rybicki, M.; Kciuk, M.; Kłosiński, K.K. From Molecules to Mind: The Critical Role of Chitosan, Collagen, Alginate, and Other Biopolymers in Neuroprotection and Neurodegeneration. Molecules 2025, 30, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibarra-Ramírez, E.; Montes, M.; Urrutia, R.A.; Reginensi, D.; Segura González, E.A.; Estrada-Petrocelli, L.; Gutierrez-Vega, A.; Appaji, A.; Molino, J. Metallic Nanoparticles Applications in Neurological Disorders: A Review. Int. J. Biomater. 2025, 2025, 4557622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Moabelo, K.L.; Fadaka, A.O.; Meyer, S.; Onani, M.O.; Madiehe, A.M.; Meyer, M. Multifunctional Gold Nanoparticles for Improved Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications: A Review. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieszawska, A.J.; Mulder, W.J.; Fayad, Z.A.; Cormode, D.P. Multifunctional gold nanoparticles for diagnosis and therapy of disease. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 831–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, K.K.; Rabha, B.; Pati, S.; Sarkar, T.; Choudhury, B.K.; Barman, A.; Bhattacharjya, D.; Srivastava, A.; Baishya, D.; Edinur, H.A.; et al. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts as Beneficial Prospect for Cancer Theranostics. Molecules 2021, 26, 6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batir-Marin, D.; Boev, M.; Cioanca, O.; Lungu, I.I.; Marin, G.A.; Burlec, A.F.; Mitran, A.M.; Mircea, C.; Hancianu, M. Exploring Oxidative Stress Mechanisms of Nanoparticles Using Zebrafish (Danio rerio): Toxicological and Pharmaceutical Insights. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, S.J.; Sheng, J.; Hosseinian, F.; Willmore, W.G. Nanoparticle Effects on Stress Response Pathways and Nanoparticle-Protein Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.S.; See, W.Z.C.; Naidu, R. Neuroprotective properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles: Therapeutic implications for Parkinson’s disease. Biosci. Rep. 2024, 44, BSR20241102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellore, J.; Pauline, C.; Amarnath, K. Bacopa monnieri Phytochemicals Mediated Synthesis of Platinum Nanoparticles and Its Neurorescue Effect on 1-Methyl 4-Phenyl 1,2,3,6 Tetrahydropyridine-Induced Experimental Parkinsonism in Zebrafish. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2013, 2013, 972391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, C.; Qu, A.; Xu, L.; Sun, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, C.; Kuang, H. Chiral Molecule-mediated Porous Cu xO Nanoparticle Clusters with Antioxidation Activity for Ameliorating Parkinson’s Disease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratihar, R.; Sankar, R. Advancements in Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Survey on Biomarker Integration and Machine Learning. Computers 2024, 13, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Lv, L.; Lu, H.; Xin, H. Advances of nano drug delivery system for the theranostics of ischemic stroke. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafi, Z.; Asha, S.; Asha, S.Y. Carbon-based nanotechnology for Parkinson’s disease: Diagnostic and therapeutic innovations. Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 2023–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Yang, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Kalvakolanu, D.V.; Cong, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Utilization of nanotechnology to surmount the blood-brain barrier in disorders of the central nervous system. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 31, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrighi, M.; Trusel, M.; Tonini, R.; Giordani, S. Carbon Nanomaterials Interfacing with Neurons: An In vivo Perspective. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, R.N.A.; Hasani, I.W.; Khafaga, D.S.R.; Kabba, S.; Farhan, M.; Aatif, M.; Muteeb, G.; Fahim, Y.A. Nanomedicine: The Effective Role of Nanomaterials in Healthcare from Diagnosis to Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Carrión, M.D.; Posadas, I. Dendrimers in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Processes 2023, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonio, M.B.; Zaki, R.M.; Elkordy, A.A. Dendrimers-Based Drug Delivery System: A Novel Approach in Addressing Parkinson’s Disease. Future Pharmacol. 2022, 2, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayab, D.E.; Din, F.U.; Ali, H.; Kausar, W.A.; Urooj, S.; Zafar, M.; Khan, I.; Shabbir, K.; Khan, G.M. Nano biomaterials based strategies for enhanced brain targeting in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: An up-to-date perspective. J. Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manimaran, V.; Nivetha, R.P.; Tamilanban, T.; Narayanan, J.; Vetriselvan, S.; Fuloria, N.K.; Chinni, S.V.; Sekar, M.; Fuloria, S.; Wong, L.S.; et al. Nanogels as novel drug nanocarriers for CNS drug delivery. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1232109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashed, E.R.; Abd El-Rehim, H.A.; El-Ghazaly, M.A. Potential efficacy of dopamine loaded-PVP/PAA nanogel in experimental models of Parkinsonism: Possible disease modifying activity. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Zhan, M.; Gao, Y.; Sun, H.; Zou, Y.; Laurent, R.; Mignani, S.; Majoral, J.P.; Shen, M.; Shi, X. Brain delivery of fibronectin through bioactive phosphorous dendrimers for Parkinson’s disease treatment via cooperative modulation of microglia. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 38, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Ma, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, S.; Kuang, Y.; Shao, K.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Han, L.; Huang, S.; et al. Angiopep-conjugated nanoparticles for targeted long-term gene therapy of Parkinson’s disease. Pharm. Res. 2013, 30, 2549–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jin, X.; Ge, Y.; Dong, J.; Liu, X.; Pei, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, B.; Chang, Y.; Yu, X.-A. Advances in brain-targeted delivery strategies and natural product-mediated enhancement of blood–brain barrier permeability. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, S.; Mamaghani, M.; Hassanikia, S.; Pilehvar, Y.; Ertas, Y.N. Exosome-powered neuropharmaceutics: Unlocking the blood-brain barrier for next-gen therapies. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X. Harnessing genetically engineered cell membrane-derived vesicles as biotherapeutics. Extracell. Vesicles Circ. Nucleic Acids 2024, 5, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Chen, W.; Deng, W. Nanocarrier-Based Systems for Targeted Delivery: Current Challenges and Future Directions. MedComm 2025, 6, e70337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, J.; Minko, T. Multifunctional and stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for targeted therapeutic delivery. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021, 18, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Qin, F.; Bu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, D.; Cen, X. Exosome-Based Therapeutics: A Natural Solution to Overcoming the Blood–Brain Barrier in Neurodegenerative Diseases. MedComm 2025, 6, e70386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izadpanah, M.; Seddigh, A.; Ebrahimi Barough, S.; Fazeli, S.A.S.; Ai, J. Potential of Extracellular Vesicles in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Indications. J. Mol. Neurosci. MN 2018, 66, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Gai, T.; Yu, H.; Su, L.; Yin, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Innovative nanocarriers: Synthetic and biomimetic strategies for enhanced drug delivery. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 34, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haney, M.J.; Yuan, H.; Shipley, S.T.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Pate, K.; Frank, J.E.; Massoud, N.; Stewart, P.W.; Perlmutter, J.S.; et al. Biodistribution of Biomimetic Drug Carriers, Mononuclear Cells, and Extracellular Vesicles, in Nonhuman Primates. Adv. Biol. 2022, 6, e2101293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zang, R.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, J.; Cheng, Z.; Wei, S.; Liu, M.; Diao, Y. Intranasal Drug Delivery Technology in the Treatment of Central Nervous System Diseases: Challenges, Advances, and Future Research Directions. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Khan, M.I.; Khan, M.U.; Khan, N.M.; Bungau, S.; Hassan, S.S.U. Applications of Extracellular Vesicles in Nervous System Disorders: An Overview of Recent Advances. Bioengineering 2022, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.U.; Shehzad, A.; Ahmed, M.B.; Lee, Y.S. Intranasal Delivery of Nanoformulations: A Potential Way of Treatment for Neurological Disorders. Molecules 2020, 25, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, S.; Fishel, I.; Offen, D. Intranasal delivery of mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles for the treatment of neurological diseases. Stem Cells 2021, 39, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Dang, S. Nanocarrier-Based Drug Delivery to Brain: Interventions of Surface Modification. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.T.T.; Kavishka, J.M.; Zhang, D.X.; Pirisinu, M.; Le, M.T.N. Extracellular Vesicles as an Efficient and Versatile System for Drug Delivery. Cells 2020, 9, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Dong, J.; Lu, Y. The blood-brain barriers: Novel nanocarriers for central nervous system diseases. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanism | Key Components | Biological Effects |

|---|---|---|

| BBB Penetration | Tetraspanins, Integrins, CXCR4/CCR2 | Cross BBB to reach substantia nigra & striatum |

| Neurotrophic Support | BDNF, GDNF | Dopaminergic neuron survival, neurite outgrowth, synaptic homeostasis |

| Antioxidant Defense | Catalase, SOD | Scavenge ROS, reduce oxidative stress |

| Pro-survival Signaling | PI3K/Akt, MAPK/ERK activators | Enhance neuronal repair and regeneration |

| miRNA Regulation | miR-7, miR-153, miR-124 | - Suppress α-synuclein expression - Enhance autophagy - Reduce apoptosis |

| Immunomodulation | TNF-α/IL-6/IL-1β inhibitors | Reduce microglial activation, limit neuroinflammation |

| α-Synuclein Clearance | Autophagy-inducing miRNAs (e.g., miR-26a) | Promote degradation of pathological α-synuclein aggregates |

| Mitochondrial Repair | Mitochondria-stabilizing factors | Improve energy metabolism, reduce ROS |

| EV Source | Unique Cargo/Properties | Therapeutic Effects | Delivery Route | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Stem Cells (NSCs) | BDNF, GDNF, neural miRNAs | - Axonal regeneration - Mitochondrial restoration | Intravenous, intranasal | Limited scalability |

| SHEDs | Anti-apoptotic miRNAs/proteins | - Reduce dopaminergic neuron loss - Lower oxidative stress | Intranasal [91,92] | Cargo variability |

| Astrocytes | Catalase, glutamate transporters | - Counteract excitotoxicity - Antioxidant effects | Local injection | Pro-inflammatory potential |

| Microglia | Engineered anti-α-synuclein antibodies | Target α-synuclein aggregates, reduce inflammation | Experimental [96] | Dual mediator/therapist role |

| iPSCs/ESCs | Dopamine precursors, synaptic miRNAs | - Dopamine synthesis - Synaptic repair | Not yet standardized | Ethical concerns (ESCs) |

| Endothelial Progenitors | Angiogenic factors | BBB repair, neurovascular support | Under investigation | Low CNS targeting efficiency |

| Feature | Liposomes | Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) | Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Spherical vesicles with one or more phospholipid bilayers | Submicron particles with a solid hydrophobic lipid core | Solid lipid core mixed with liquid lipids creating a less ordered lipid matrix |

| Drug Encapsulation | Encapsulate hydrophilic drugs in aqueous core and lipophilic drugs in bilayer | Encapsulate both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs in solid lipid matrix | Higher drug loading capacity than SLNs due to disrupted lipid matrix from liquid lipid |

| Stability | Moderate stability but prone to leakage and fusion | More physically stable than liposomes but can undergo drug expulsion due to lipid crystallization | Improved stability over SLNs; liquid lipids reduce crystallinity and drug expulsion |

| Drug Release Profile | Often faster release, sometimes burst effect | Controlled and sustained release, dependent on lipid matrix | More controlled and modifiable release than SLNs, better long-term stability |

| BBB Penetration | Good BBB transport, can be surface-engineered for enhanced targeting | Efficient BBB crossing with potential targeting ligand modification | Effective BBB penetration with enhanced targeting potential |

| Biocompatibility | Highly biocompatible, mimics cell membranes | Biocompatible, made from physiological lipids | Biocompatible, with improved flexibility in composition |

| Production Complexity | More complex and costly, often requires organic solvents | Easier and scalable production with less solvent use | Similar to SLNs but improved formulation parameters |

| Use in PD Models | Delivery of neurotrophic factors (e.g., GDNF), dopamine agonists; enhances neuronal uptake via fusion | Delivery of dopaminergic drugs (e.g., levodopa, ropinirole), antioxidants; sustained neuroprotection | Improved delivery of neuroprotective agents with higher drug loading and stability; investigational in PD models |

| Clinical Potential | Historically favored but limited by stability | Increasingly favored due to stability and controlled release | Emerging as superior alternatives to SLNs due to better encapsulation and stability |

| Nanocarrier Type | Key Features | Therapeutic Applications in PD | Advantages | Limitations/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanocarriers (Liposomes, SLNs, NLCs) | Membrane-like lipid bilayers or lipid matrices; can load hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs | Dopamine replacement, neurotrophic factors (e.g., GDNF), antioxidants, neuroprotective compounds | High biocompatibility, good BBB penetration, sustained release, versatile routes (IN, IV, oral); NLCs allow higher drug loading and stability | Liposomes less stable (leakage, fusion); SLNs risk drug expulsion; scalability challenges |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles (PNPs) | Biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLGA, PCL, chitosan); tunable drug release | Levodopa, dopamine, retinoic acid, neurotrophic factors, gene delivery | Controlled release, surface modification for BBB targeting, multifunctional (drug/gene/protein delivery), flexible routes (IN, IV, transdermal) | Manufacturing complexity; variability in drug encapsulation; long-term safety data limited |

| Metallic Nanoparticles (MNPs) | Gold, silver, selenium, zinc oxide, iron oxide; high surface reactivity | Antioxidant effects, α-synuclein inhibition, biomarker detection, theranostics | Intrinsic catalytic (“nanozyme”) activity, dual therapeutic and diagnostic potential, surface functionalization for targeting | Risk of toxicity/oxidative imbalance; clearance and long-term safety concerns |

| Carbon-Based Nanoparticles (CBNPs) | Graphene, carbon nanotubes, fullerenes; unique electrical and mechanical properties | Dopamine delivery, inhibition of α-synuclein aggregation, antioxidant/anti-inflammatory effects | Strong BBB penetration, potential disease-modifying activity, high drug-loading capacity, theranostic potential | Biocompatibility and toxicity concerns; functionalization needed for safe use |

| Nanogels and Dendrimers | Cross-linked hydrophilic polymers (nanogels) or branched polymers (dendrimers) | Dopamine delivery, pramipexole, rotigotine, gene therapy, microglia-targeted anti-inflammatory agents | High drug encapsulation, stimuli-responsive release, BBB penetration, inherent neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects, theranostic potential | Complex synthesis, stability issues, need for more clinical validation |

| Feature | Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) | Synthetic Nanocarriers (Lipids, Polymers, Metals, Carbon, Nanogels) |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Origin | Naturally secreted by cells (MSC, NSC, SHED, glia, iPSC, etc.); carry proteins, miRNAs, enzymes | Artificially engineered using lipids, polymers, metals, carbon, or dendrimers |

| Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) Penetration | Intrinsic ability via receptor-mediated transcytosis (integrins, tetraspanins, CXCR4/CCR2); effective intranasally | Limited natural BBB penetration; often requires surface modifications or disruptive methods |

| Cargo | Endogenous bioactive molecules (BDNF, GDNF, catalase, SOD, miRNAs regulating α-synuclein, apoptosis, autophagy) | Drugs (levodopa, dopamine agonists), growth factors, antioxidants, siRNA, proteins; loaded synthetically |

| Mechanisms of Action | Multi-modal: neuroprotection, immunomodulation, α-synuclein clearance, mitochondrial repair, synaptic plasticity | Mainly symptomatic relief (dopamine delivery), antioxidant/anti-inflammatory action; limited intrinsic biology |

| Targeting | Some natural tropism (e.g., neural-derived EVs → CNS); engineering possible but may affect stability | Targeting mainly via chemical/biological modification (ligands, peptides, antibodies) |

| Biodistribution | Source-dependent tropism; accumulate in CNS more effectively via intranasal route | Often cleared rapidly by liver, spleen, kidney; peripheral accumulation common |

| Safety & Immunogenicity | Generally low immunogenicity, good biocompatibility; long-term safety still under study | Material-dependent; some risk of toxicity, oxidative stress, or inflammation |

| Scalability | Low natural yield; heterogeneity, reproducibility, and regulatory standardization are major barriers | More scalable manufacturing; established protocols for large-scale production |

| Theranostic Potential | Can serve as both biomarkers (α-syn, DJ-1, miRNAs) and therapies (theranostic EVs emerging) | Mainly therapeutic or diagnostic, rarely both; theranostics mostly in experimental stages |

| Clinical Status | Preclinical efficacy in PD models; early-stage safety trials ongoing; no completed PD clinical trials yet | More advanced in drug delivery field; some CNS nanocarrier trials exist, but BBB remains a bottleneck |

| Unique Strengths | Natural biology, endogenous cargo, multi-modal mechanisms, BBB penetration | Engineering flexibility, reproducibility, controlled cargo loading |

| Main Challenges | Scalability, heterogeneity, incomplete mechanistic understanding, regulatory gaps | BBB penetration, toxicity, long-term safety, limited intrinsic therapeutic functions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muttiah, B.; Abdullah, N.A.H. From Bench to Brain: Translating EV and Nanocarrier Research into Parkinson’s Disease Therapies. Biology 2025, 14, 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101349

Muttiah B, Abdullah NAH. From Bench to Brain: Translating EV and Nanocarrier Research into Parkinson’s Disease Therapies. Biology. 2025; 14(10):1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101349

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuttiah, Barathan, and Nur Atiqah Haizum Abdullah. 2025. "From Bench to Brain: Translating EV and Nanocarrier Research into Parkinson’s Disease Therapies" Biology 14, no. 10: 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101349

APA StyleMuttiah, B., & Abdullah, N. A. H. (2025). From Bench to Brain: Translating EV and Nanocarrier Research into Parkinson’s Disease Therapies. Biology, 14(10), 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101349