The Clinical Role of Serum Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 3 in Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Patients with Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Measurement of Serum ERBB3

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

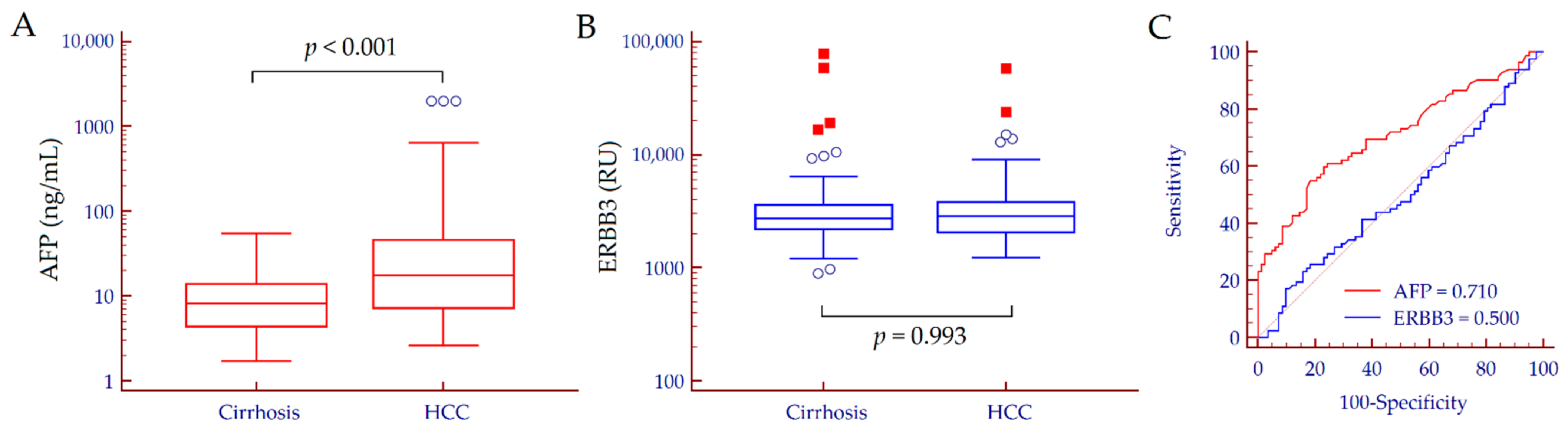

3.1. Diagnostic Accuracy of Serum ERBB3 for the Detection of HCC

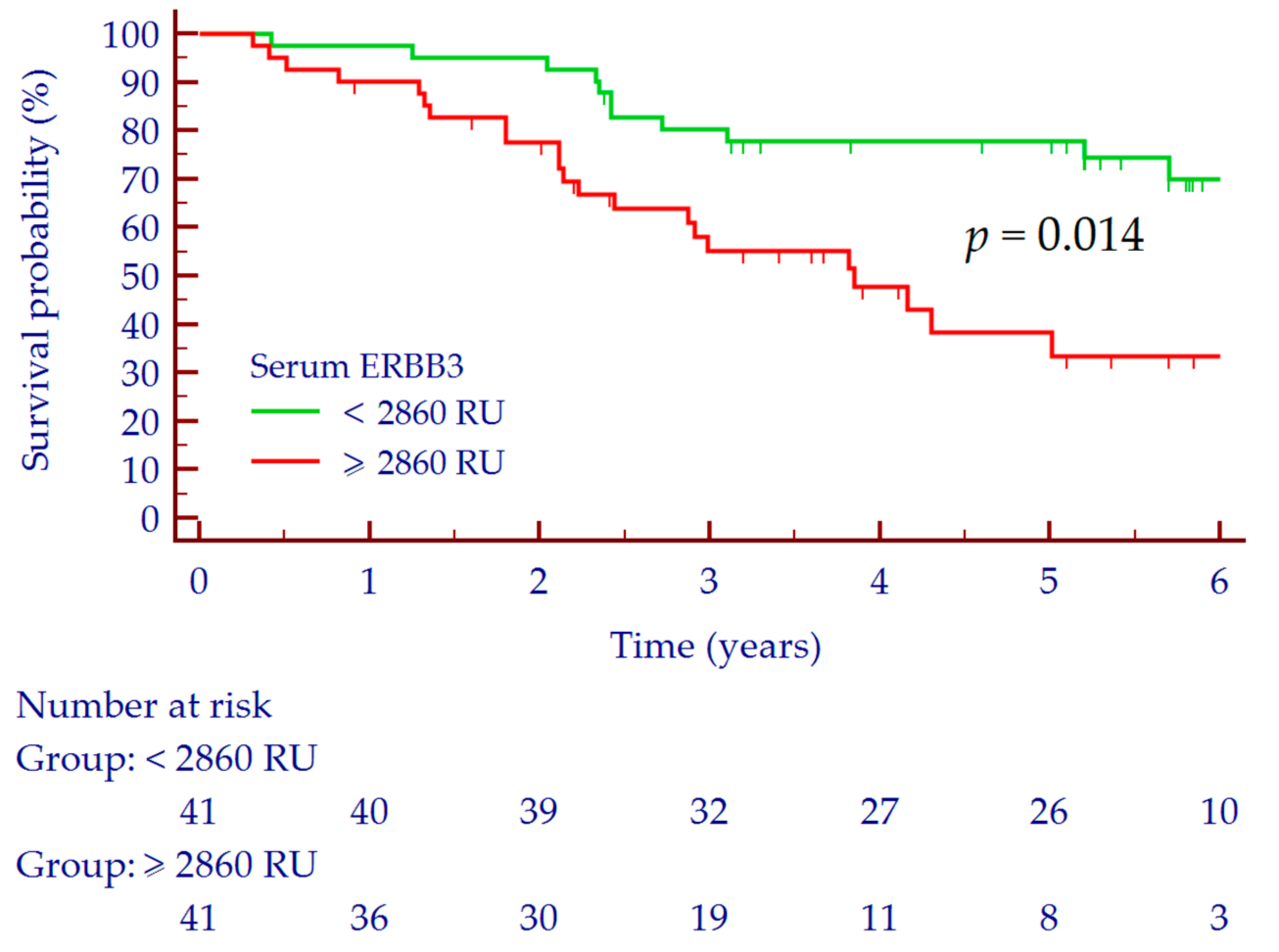

3.2. Prediction of Overall Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Global Cancer Observatory-IARC. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today (accessed on 11 June 2019).

- Caviglia, G.P.; Rosso, C.; Fagoonee, S.; Saracco, G.M.; Pellicano, R. Liver fibrosis: The 2017 state of art. Panminerva Med. 2017, 59, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiovanni, A.; Prati, G.M.; Fasani, P.; Ronchi, G.; Romeo, R.; Manini, M.; Del Ninno, E.; Morabito, A.; Colombo, M. The natural history of compensated cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus: A 17-year cohort study of 214 patients. Hepatology 2006, 43, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ružić, M.; Pellicano, R.; Fabri, M.; Luzza, F.; Boccuto, L.; Brkić, S.; Abenavoli, L. Hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma: A narrative review. Panminerva Med. 2018, 60, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Cai, N.; Fan, J.; Mao, X.; Suo, C.; Jin, L.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X. Global trend of aetiology-based primary liver cancer incidence from 1990 to 2030: A modelling study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caviglia, G.P.; Ciruolo, M.; Olivero, A.; Carucci, P.; Rolle, E.; Rosso, C.; Abate, M.L.; Risso, A.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Tandoi, F.; et al. Prognostic Role of Serum Cytokeratin-19 Fragment (CYFRA 21-1) in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrero, J.A.; Kulik, L.M.; Sirlin, C.B.; Zhu, A.X.; Finn, R.S.; Abecassis, M.M.; Roberts, L.R.; Heimbach, J.K. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018, 68, 723–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.; Volk, M.L.; Waljee, A.; Salgia, R.; Higgins, P.; Rogers, M.A.; Marrero, J.A. Meta-analysis: Surveillance with ultrasound for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 30, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, D.; Tucci, A.; Ponzo, P.; Caviglia, G.P. Non-invasive biomarkers for the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Minerva Biotecnol. 2019, 31, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L.E.; Longo, J.F.; Carroll, S.L. Mechanisms of Receptor Tyrosine-Protein Kinase ErbB-3 (ERBB3) Action in Human Neoplasia. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 1898–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maennling, A.E.; Tur, M.K.; Niebert, M.; Klockenbring, T.; Zeppernick, F.; Gattenlöhner, S.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Hussain, A.F. Molecular Targeting Therapy against EGFR Family in Breast Cancer: Progress and Future Potentials. Cancers 2019, 11, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z. ErbB Receptors and Cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1652, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, A.; Libring, S.; Alpsoy, A.; Abdullah, A.; Schaber, J.A.; Solorio, L.; Wendt, M.K. Autocrine Fibronectin Inhibits Breast Cancer Metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, A.; Hardy, S.D.; Kim, D.; Akhand, S.S.; Jolly, M.K.; Wang, W.H.; Anderson, J.C.; Khodadadi, R.B.; Brown, W.S.; George, J.T.; et al. Spleen Tyrosine Kinase-Mediated Autophagy Is Required for Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity and Metastasis in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 1831–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, A.; Paez, J.S.; Libring, S.; Hopkins, K.; Solorio, L.; Wendt, M.K. Transglutaminase-2 facilitates extracellular vesicle-mediated establishment of the metastatic niche. Oncogenesis 2020, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.Y.; He, J.R.; Yu, M.C.; Lee, W.C.; Chen, T.C.; Lo, S.J.; Bera, R.; Sung, C.M.; Chiu, C.T. Secreted ERBB3 isoforms are serum markers for early hepatoma in patients with chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 4715–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannelli, G.; Santoro, A.; Kelley, R.K.; Gane, E.; Paradis, V.; Cleverly, A.; Smith, C.; Estrem, S.T.; Man, M.; Wang, S.; et al. Biomarkers and overall survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with TGF-βRI inhibitor galunisertib. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0222259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviglia, G.P.; Touscoz, G.A.; Smedile, A.; Pellicano, R. Noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis: Key messages for clinicians. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2014, 124, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaia, S.; Campion, D.; Evangelista, A.; Spandre, M.; Cosso, L.; Brunello, F.; Ciccone, G.; Bugianesi, E.; Rizzetto, M. Non-invasive score system for fibrosis in chronic hepatitis: Proposal for a model based on biochemical, FibroScan and ultrasound data. Liver Int. 2015, 35, 2027–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Abronzo, L.S.; Pan, C.X.; Ghosh, P.M. Evaluation of Protein Levels of the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase ErbB3 in Serum. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1655, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowicz, B.; Winter, P.; Fuksiewicz, M.; Jagiello-Gruszfeld, A.I.; Nowecki, N.; Kowalska, M.M. Clinical value of HER3/ErbB3 serum level determination in patients with breast cancer qualified for neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, S15–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricco, G.; Cavallone, D.; Cosma, C.; Caviglia, G.P.; Oliveri, F.; Biasiolo, A.; Abate, M.L.; Plebani, M.; Smedile, A.; Bonino, F.; et al. Impact of etiology of chronic liver disease on hepatocellular carcinoma biomarkers. Cancer Biomark. 2018, 21, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buta, C.; Benabou, E.; Lequoy, M.; Régnault, H.; Wendum, D.; Meratbene, F.; Chettouh, H.; Aoudjehane, L.; Conti, F.; Chrétien, Y.; et al. Heregulin-1ß and HER3 in hepatocellular carcinoma: Status and regulation by insulin. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2016, 35, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, S.; López-Cortés, A.; Indacochea, A.; García-Cárdenas, J.M.; Zambrano, A.K.; Cabrera-Andrade, A.; Guevara-Ramírez, P.; González, D.A.; Leone, P.E.; Paz-Y-Miño, C. Analysis of Racial/Ethnic Representation in Select Basic and Applied Cancer Research Studies. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanasekaran, R.; Bandoh, S.; Roberts, L.R. Molecular pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma and impact of therapeutic advances. F1000Research 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Goto, T.; Hirotsu, Y.; Moriyama, M.; Omata, M. Molecular Mechanisms Driving Progression of Liver Cirrhosis towards Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B and C Infections: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masroor, M.; Javid, J.; Mir, R.; Prasant, Y.; Imtiyaz, A.; Mariyam, Z.; Mohan, A.; Ray, P.C.; Saxena, A. Prognostic significance of serum ERBB3 and ERBB4 mRNA in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredemeier, M.; Edimiris, P.; Tewes, M.; Mach, P.; Aktas, B.; Schellbach, D.; Wagner, J.; Kimmig, R.; Kasimir-Bauer, S. Establishment of a multimarker qPCR panel for the molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells in blood samples of metastatic breast cancer patients during the course of palliative treatment. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 41677–41690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocana, A.; Vera-Badillo, F.; Seruga, B.; Templeton, A.; Pandiella, A.; Amir, E. HER3 overexpression and survival in solid tumors: A meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Xie, D.; Li, J.J.; Cheng, S.; Ma, X. Epithelial V-like antigen 1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth and metastasis via the ERBB-PI3K-AKT pathway. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 1500–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinway, S.N.; Dang, H.; You, H.; Rountree, C.B.; Ding, W. The EGFR/ErbB3 Pathway Acts as a Compensatory Survival Mechanism upon c-Met Inhibition in Human c-Met+ Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A.; Trevisani, F.; Farinati, F.; Cillo, U. Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Precision Medicine Era: From Treatment Stage Migration to Therapeutic Hierarchy. Hepatology 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, A.; Reig, M.; Bruix, J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2018, 391, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omata, M.; Cheng, A.L.; Kokudo, N.; Kudo, M.; Lee, J.M.; Jia, J.; Tateishi, R.; Han, K.H.; Chawla, Y.K.; Shiina, S.; et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: A 2017 update. Hepatol. Int. 2017, 11, 317–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Cirrhosis | HCC | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 82 | 82 | |

| Age (years), median (range) | 58 (49–82) | 67 (45–89) | <0.001 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 52 (63%) | 65 (79%) | 0.038 |

| ALT (U/L), median (IQR) | 58 (33–89) | 67 (36–126) | 0.019 |

| AST (U/L), median (IQR) | 59 (31–73) | 82 (47–132) | <0.001 |

| Platelets (× 109/L), median (IQR) | 139 (88–187) | 97 (68–124) | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL), median (IQR) | 4.1 (3.8–4.4) | 3.9 (3.3–4.1) | <0.001 |

| INR, median (IQR) | 1.07 (1.00–1.16) | 1.15 (1.06–1.26) | 0.007 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | 0.010 |

| AFP (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 8.2 (4.4–14.0) | 17.5 (7.3–46.0) | <0.001 |

| Child–Pugh Score | |||

| A, n (%) | 80 (98%) | 71 (87%) | 0.018 |

| B, n (%) | 2 (2%) | 11 (13%) | |

| BCLC Stage | |||

| 0, n (%) | 23 (28%) | ||

| A, n (%) | 59 (62%) | ||

| HCC nodules | |||

| 1, n (%) | 51 (62%) | ||

| 2, n (%) | 19 (23%) | ||

| 3, n (%) | 12 (15%) | ||

| Size of major nodule (mm), median (IQR) | 18 (15–24) |

| Characteristics | HR, 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.01, 0.98–1.05 | 0.370 |

| Child–Pugh Score, B | 0.77, 0.26–2.26 | 0.770 |

| BCLC Score, A | 1.40, 0.66–2.98 | 0.377 |

| Serum ERBB3 ≥ 2860 RU | 2.24, 1.16–4.35 | 0.017 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caviglia, G.P.; Abate, M.L.; Rolle, E.; Carucci, P.; Armandi, A.; Rosso, C.; Olivero, A.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Tandoi, F.; Saracco, G.M.; et al. The Clinical Role of Serum Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 3 in Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Patients with Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biology 2021, 10, 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10030215

Caviglia GP, Abate ML, Rolle E, Carucci P, Armandi A, Rosso C, Olivero A, Ribaldone DG, Tandoi F, Saracco GM, et al. The Clinical Role of Serum Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 3 in Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Patients with Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biology. 2021; 10(3):215. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10030215

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaviglia, Gian Paolo, Maria Lorena Abate, Emanuela Rolle, Patrizia Carucci, Angelo Armandi, Chiara Rosso, Antonella Olivero, Davide Giuseppe Ribaldone, Francesco Tandoi, Giorgio Maria Saracco, and et al. 2021. "The Clinical Role of Serum Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 3 in Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Patients with Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma" Biology 10, no. 3: 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10030215

APA StyleCaviglia, G. P., Abate, M. L., Rolle, E., Carucci, P., Armandi, A., Rosso, C., Olivero, A., Ribaldone, D. G., Tandoi, F., Saracco, G. M., Ciancio, A., Bugianesi, E., & Gaia, S. (2021). The Clinical Role of Serum Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 3 in Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Patients with Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biology, 10(3), 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10030215