Preparation of an ABS-ZnO Composite for 3D Printing and the Influence of Printing Process on Printing Quality

Highlights

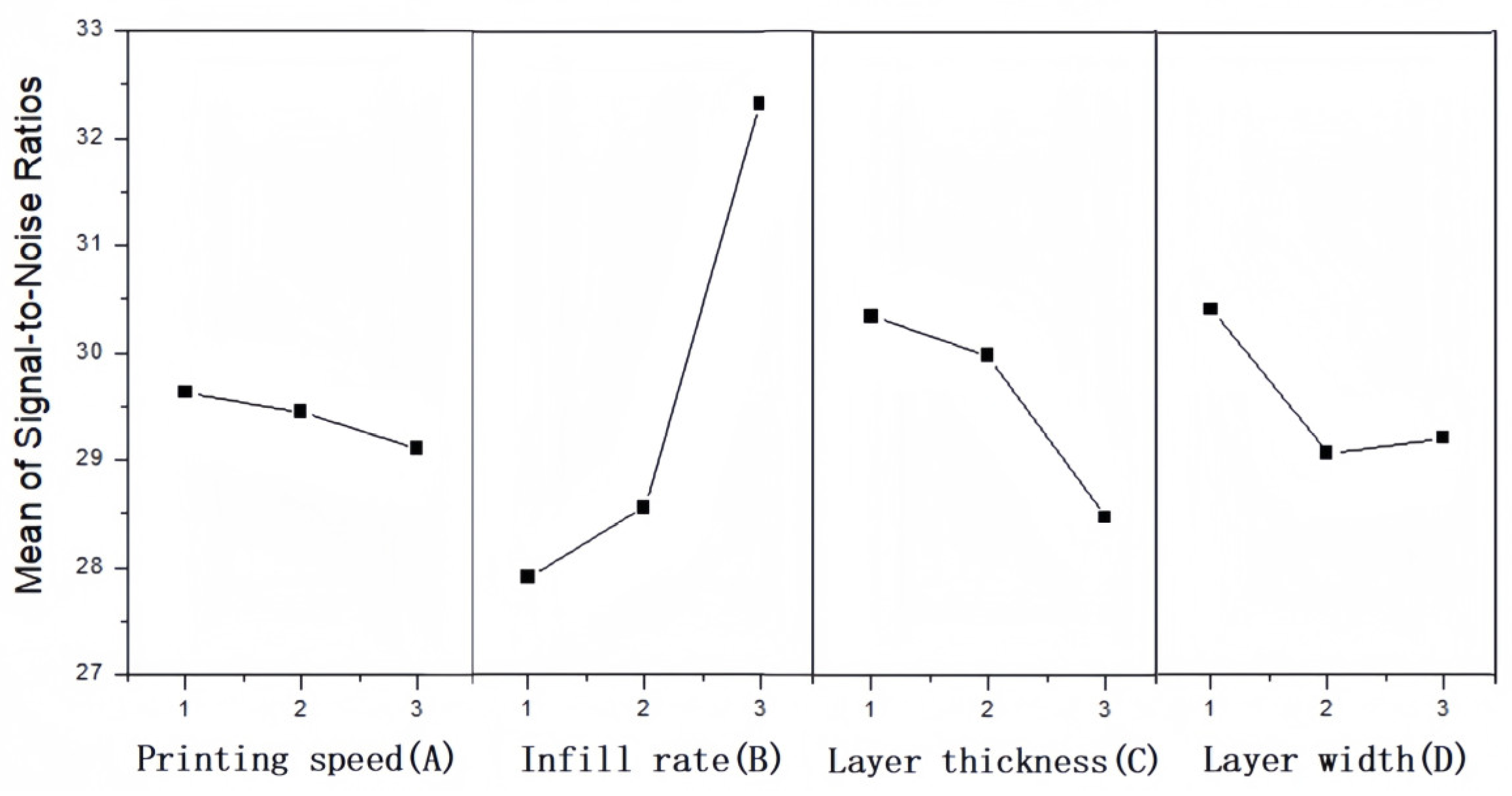

- ABS-ZnO composite filaments were fabricated for fused deposition modeling 3D printing, and the influences of printing process parameters on the mechanical properties and surface roughness of printed specimens were systematically explored.

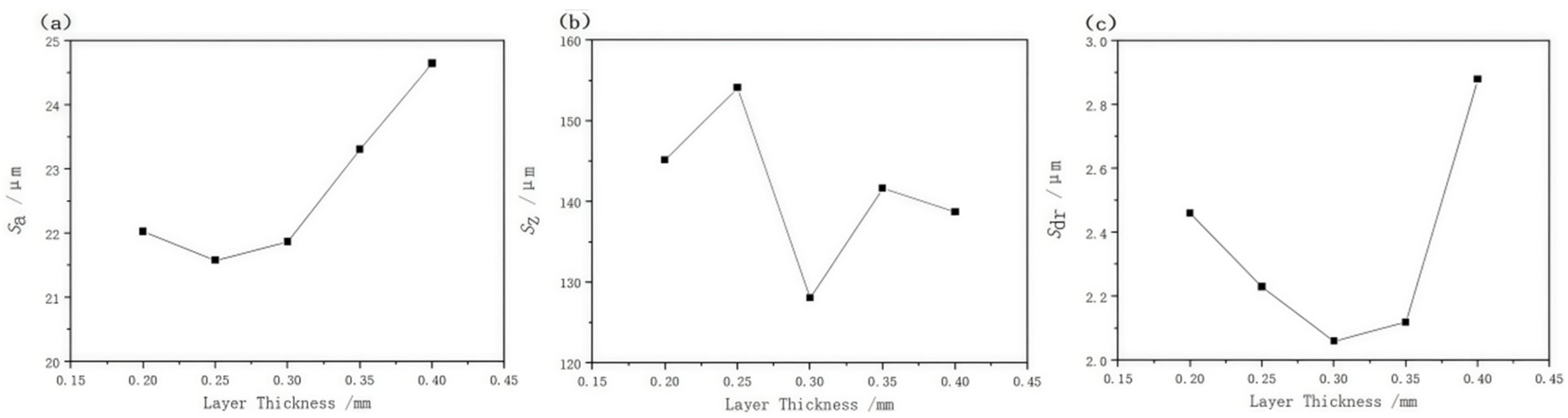

- The filling ratio is identified as the dominant factor governing the mechanical properties of printed parts, whereas surface roughness is significantly affected by printing temperature and layer thickness. This work provides valuable guidance for enhancing the printing quality and optimizing the processing parameters of ABS-ZnO composites.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preparation of ABS-ZnO Materials for FDM 3D Printing

3. Experiments and Method

3.1. 3D Printing Process Experiments

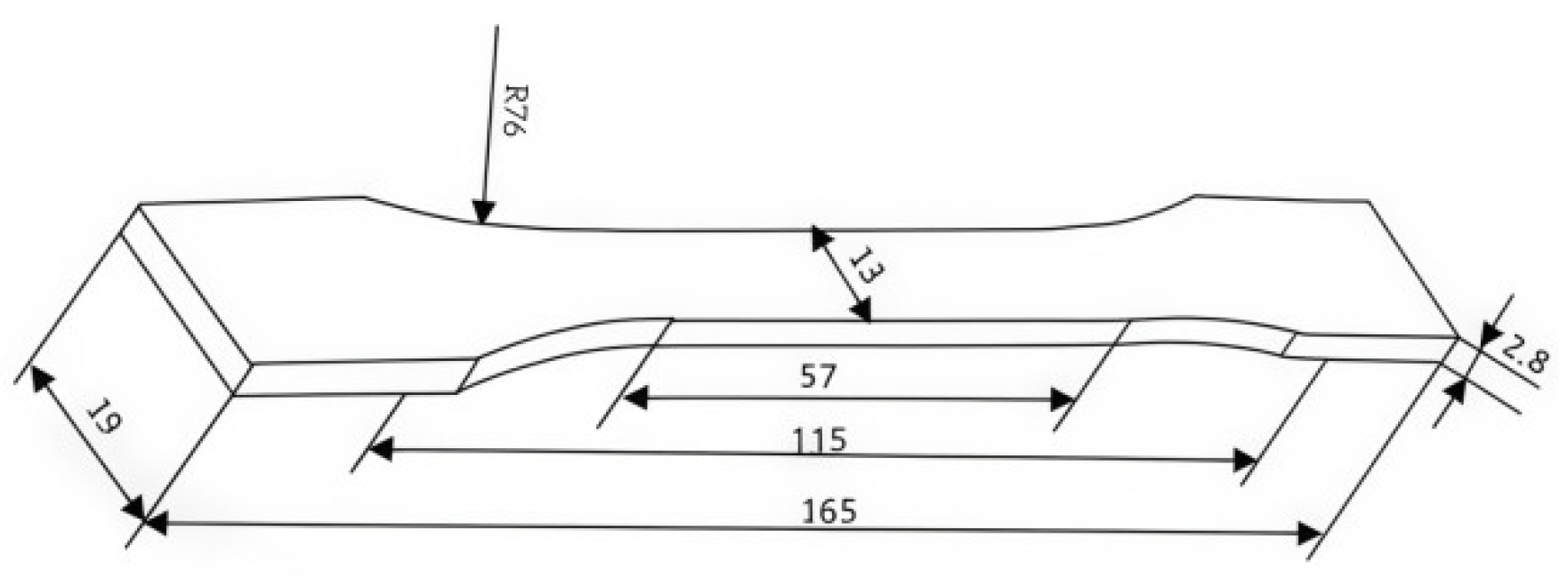

3.2. Sample Characterization

4. Results and Discussion

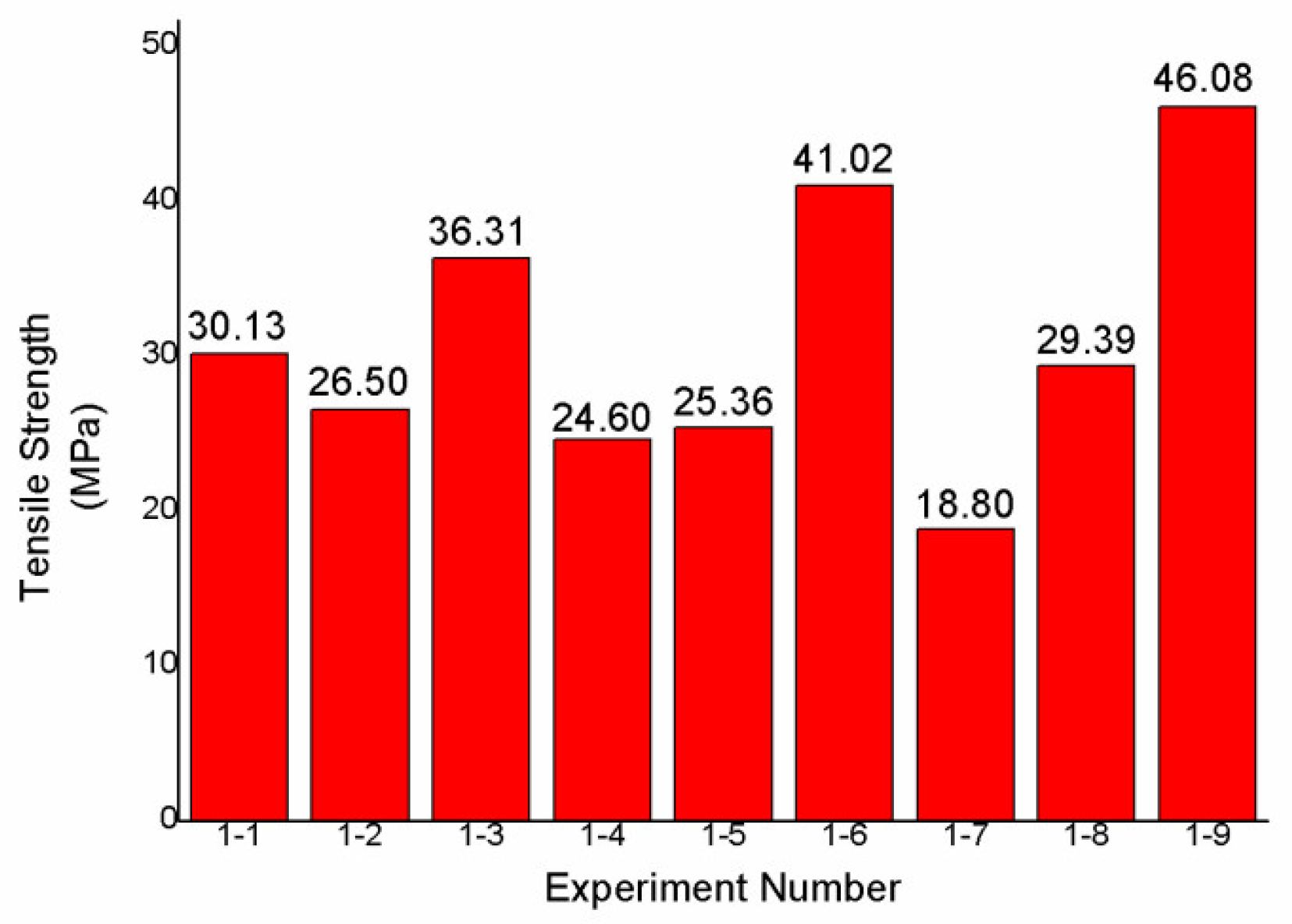

4.1. Tensile Tests and Analysis

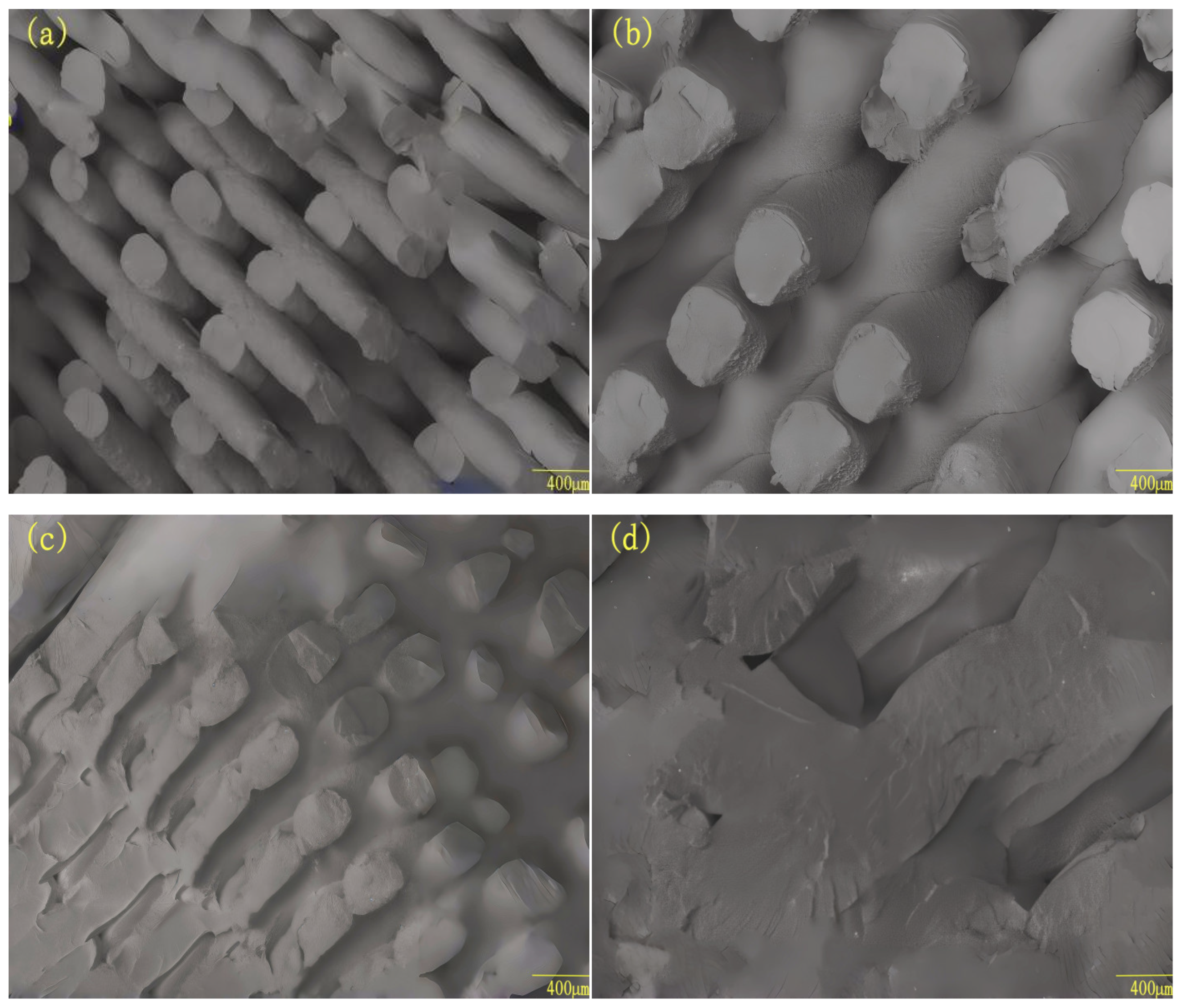

4.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

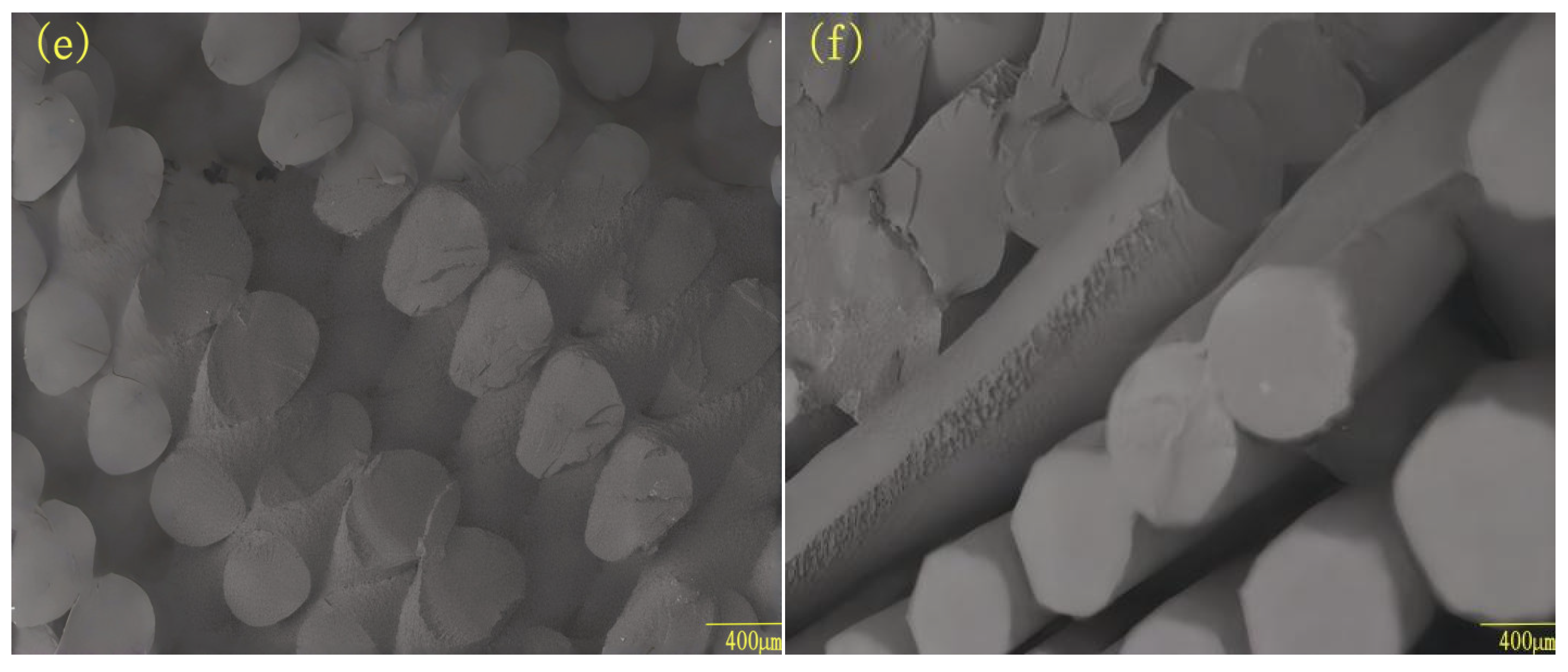

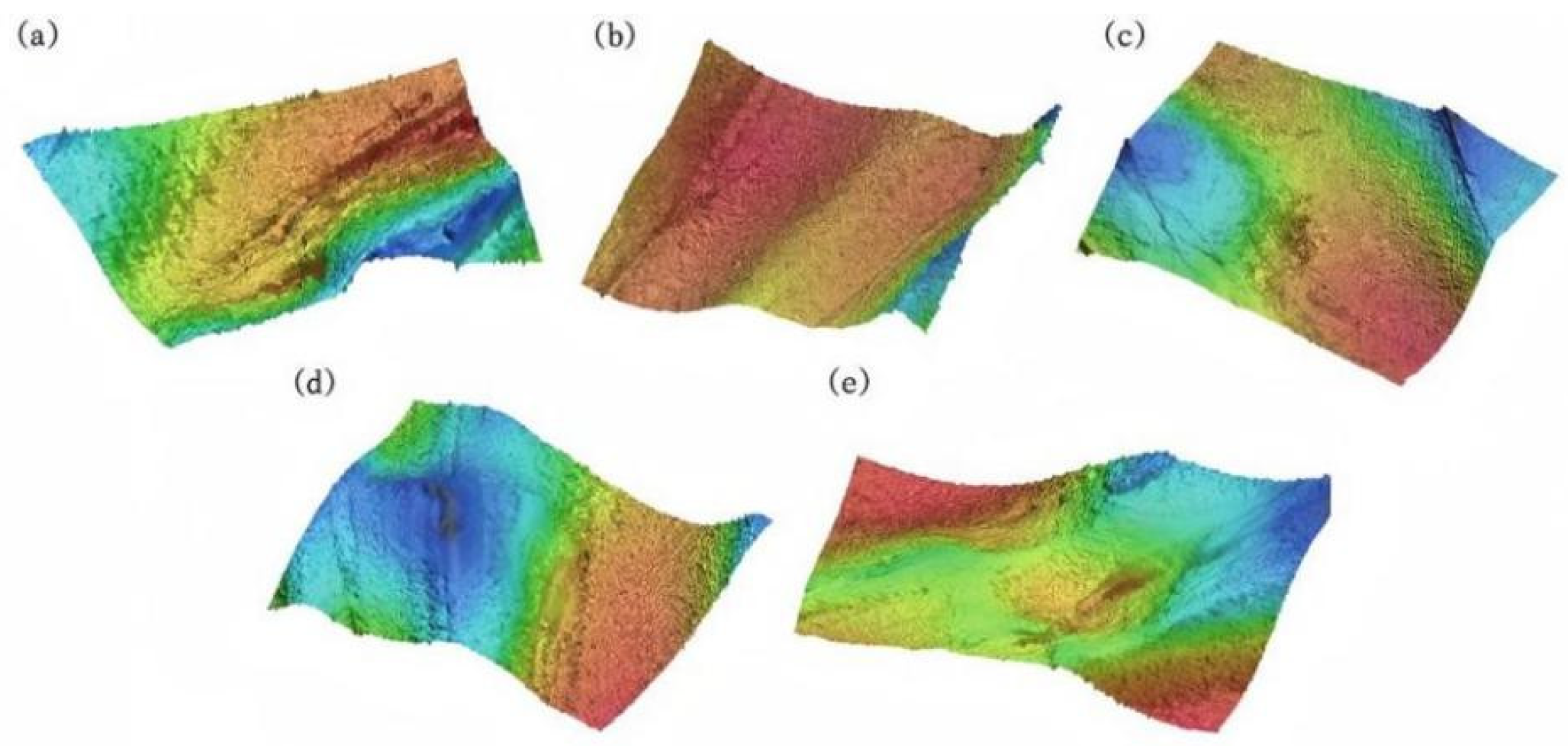

4.3. Surface Roughness Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Hui, D.; Qiu, J.; Wang, S. 3D bioprinting of soft materials-based regenerative vascular structures and tissues. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 123, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, G.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, H. Research progress on 3D printed geopolymer materials. Vibroeng. Procedia 2025, 59, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Tian, X.; Kang, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, T.; Zhang, H.; Wen, Y.; Lei, M.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C.; et al. Progress in 3D Printing of Polymer and Composites for On-Orbit Structure Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. Front. 2025, 4, 200234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Lou, H.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H.; Li, Z.; Yue, X.; Kong, W.; Yang, H.; et al. Progress in the integration of 3D printing technology with photothermal materials for osteosarcoma treatment. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Cheng, X.; Dong, R.; Liu, H.; Zheng, G.; He, L.; Wang, W.; Tan, K. Study of thermal stress deformation in hybrid 3D printing and milling process of PEEK material. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2025, 239, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, M.; Sürer, E.; Ucar, Y.; Aygün, E.B.G. Evaluating the Mechanical Properties and Fracture Surfaces of Interim Restorative Materials Produced by Different Three-Dimensional Printer Technologies: An In-Vitro Study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sun, H.; Dong, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B. Bending-Induced Progressive Damage of 3D-Printed Sandwich-Structured Composites by Non-Destructive Testing. Polymers 2025, 17, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, F.; Rezadoust, A.M.; Sadjadi, S.; Atai, M. 3D-printed cyclodextrin polymer-g-C3N4 nanocomposite as a monolithic adsorbent for dye removal. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 11, 1317–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balina, K.; Gailitis, R.; Sinka, M.; Argalis, P.P.; Radina, L.; Sprince, A. Prospective LCA for 3D-Printed Foamed Geopolymer Composites Using Construction Waste as Additives. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.A.; Kryukov, O.; Bandela, A.K.; Muadi, H.; Ashkenasy, N.; Cohen, S.; Marks, R.S. Development of Covalently Functionalized Alginate–Pyrrole and Polypyrrole–Alginate Nanocomposites as 3D Printable Electroconductive Bioinks. Materials 2025, 18, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, G.; Sacchi, F.; Bondioli, F.; Messori, M. 3D printing of lignin-based polymeric composites obtained using liquid crystal display as a vat photopolymerization technique. Polym. Int. 2025, 74, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, A.; Wolde, J.G.; Joda, A. The Potential of Sand as a Sustainable Infill for 3D Concrete Printed Building Walls. Heat Transf. 2025, 54, 2912–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.C.; He, F.Y.; Khan, M. An empirical torsional spring model for the inclined crack in a 3D-printed acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) cantilever beam. Polymers 2023, 15, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Vellaisamy, M.; Gupta, S.K.; Veeman, D.; Katiyar, J.K. Physico-tribo-mechanical Performance of Banana Peel Powder Reinforced PLA-based 3D printed Biocomposites. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 2026, 240, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, H.; Qian, Z.; Xue, B.; Zhang, J.; Agyenim-Boateng, E.; Zhou, J. Mechanical Properties of 4D Printed Origami Honeycomb Metamaterials Based on Nano-Fe3O4 Shape Memory Polymer Composites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2025, 65, 6622–6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, A.; Hakim, M.L.; Herianto, H.; Rifai, A.P. Flexural performance and interfacial bonding of PLA/ABS/HIPS composites in multi-nozzle 3D printing. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2025, 48, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahouti, T.; Örnek, E.; Çevir, B.; Berber, H.; Belen, M.A.; Sadıkoğlu, H.; Yilmazer, H. SLA-Printed BaTiO3-Reinforced Bio-Nanocomposites: Influence of Printing Parameters on Mechanical, Dielectric, and Thermal Properties. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 53350–53363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Xinglong, W.; Jiaqi, W.; Xin, W.; Xianglong, L.; Yue, Z.; Ying, L.; Yuehui, H.; et al. A general strategy for constructing robust superhydrophobic and self-healing coatings based on waterborne polyurethane with dynamic covalent bonds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 47033–47041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.D.; Shi, L.; Liu, M.M.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, R.; Zheng, X. Removal of viral aerosols by 3D-printed visible photocatalytic system with mixed substrates. China Environ. Sci. 2020, 40, 5055–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidakis, N.; Petousis, M.; Maniadi, A.; Koudoumas, E.; Kenanakis, G.; Romanitan, C.; Tutunaru, O.; Suchea, M.; Kechagias, J. The Mechanical and Physical Properties of 3D-Printed Materials Composed of ABS-ZnO Nanocomposites and ABS-ZnO Microcomposites. Micromachines 2020, 11, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aw, Y.Y.; Yeoh, C.K.; Idris, M.A.; Teh, P.L.; Elyne, W.N.; Hamzah, K.A.; Sazali, S.A. Influence of Filler Precoating and Printing Parameter on Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene/Zinc Oxide Composite. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2019, 58, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D638-22; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

| Material | Elastic Modulus | Density | Poisson’s Ratio | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABS | 2.3 GPa | 1.05 g/cm3 | 0.36 | 1.5 mm |

| ZnO | 110 GPa | 5.61 g/cm3 | 0.28 | 100 nm |

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Printing speed | A | mm/s | 200 | 250 | 300 |

| Infill rate | B | % | 50 | 70 | 90 |

| Layer thickness | C | mm | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Layer width | D | mm | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Experiment Number | A | B | C | D | Parameter Combination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 mm/s-50%-0.2 mm-0.4 mm |

| 1-2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 200 mm/s-70%-0.3 mm-0.6 mm |

| 1-3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 200 mm/s-90%-0.4 mm-0.8 mm |

| 1-4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 250 mm/s-50%-0.3 mm-0.8 mm |

| 1-5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 250 mm/s-70%-0.4 mm-0.4 mm |

| 1-6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 250 mm/s-90%-0.2 mm-0.6 mm |

| 1-7 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 300 mm/s-50%-0.4 mm-0.6 mm |

| 1-8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 300 mm/s-70%-0.2 mm-0.8 mm |

| 1-9 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 300 mm/s-90%-0.3 mm-0.4 mm |

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degree of Freedom | Contribution Rate | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Printing speed (A) | 0.565 | 2 | 3.23% | - | - |

| Infill rate (B) | 240.000 | 2 | 87.48% | 424.78 | ˂0.01 |

| Layer thickness (C) | 124.700 | 2 | 48.32% | 220.70 | ˂0.01 |

| Layer width (D) | 62.51 | 2 | 25.39% | 110.64 | ˂0.01 |

| Experiment Number | Infill Rate | Layer Thickness | Layer Width | Print Speed | Tensile Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-1 | 50% | 0.2 mm | 0.4 mm | 200 mm/s | 30.06 MPa |

| 2-2 | 70% | 0.2 mm | 0.4 mm | 200 mm/s | 31.46 MPa |

| 2-3 | 90% | 0.2 mm | 0.4 mm | 200 mm/s | 48.37 MPa |

| 2-4 | 90% | 0.4 mm | 0.4 mm | 200 mm/s | 42.19 MPa |

| 2-5 | 70% | 0.2 mm | 0.8 mm | 200 mm/s | 28.34 MPa |

| 2-6 | 70% | 0.4 mm | 0.8 mm | 200 mm/s | 23.81 MPa |

| Experiment Number | Porosity | Structural Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 2-1 | 73.26% | Parallel filaments with medium diameter |

| 2-2 | 75.52% | Parallel filaments with medium diameter |

| 2-3 | 18.23% | Dense fibers with medium diameter |

| 2-4 | 30.14% | Dense fibers with large diameter |

| 2-5 | 77.13% | Dispersed fine filaments |

| 2-6 | 82.64% | Dispersed fine filaments |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y. Preparation of an ABS-ZnO Composite for 3D Printing and the Influence of Printing Process on Printing Quality. Fibers 2026, 14, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib14020019

Du C, Zhao Y, Li Y. Preparation of an ABS-ZnO Composite for 3D Printing and the Influence of Printing Process on Printing Quality. Fibers. 2026; 14(2):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib14020019

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Chao, Yali Zhao, and Yong Li. 2026. "Preparation of an ABS-ZnO Composite for 3D Printing and the Influence of Printing Process on Printing Quality" Fibers 14, no. 2: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib14020019

APA StyleDu, C., Zhao, Y., & Li, Y. (2026). Preparation of an ABS-ZnO Composite for 3D Printing and the Influence of Printing Process on Printing Quality. Fibers, 14(2), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib14020019