Mitigating Out-of-Plane Fiber Waviness in AFP Laminates with Tow-Gaps via Selective Placement of Thermoplastic Veils

Highlights

- Selective placement of thermoplastic veils within AFP tow-gaps reduces ply sinking, surface waviness, and fiber misalignment.

- Veils transform resin-rich regions into reinforced networks, improving laminate mechanical and morphological uniformity.

- Tensile testing and progressive failure simulations demonstrate that veil placement restores stiffness and induces changes in failure behavior.

- Controlling morphology through targeted veil placement enhances composite reliability without weight increase.

- The method offers an approach for mitigating AFP tow gap induced defects.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimentation

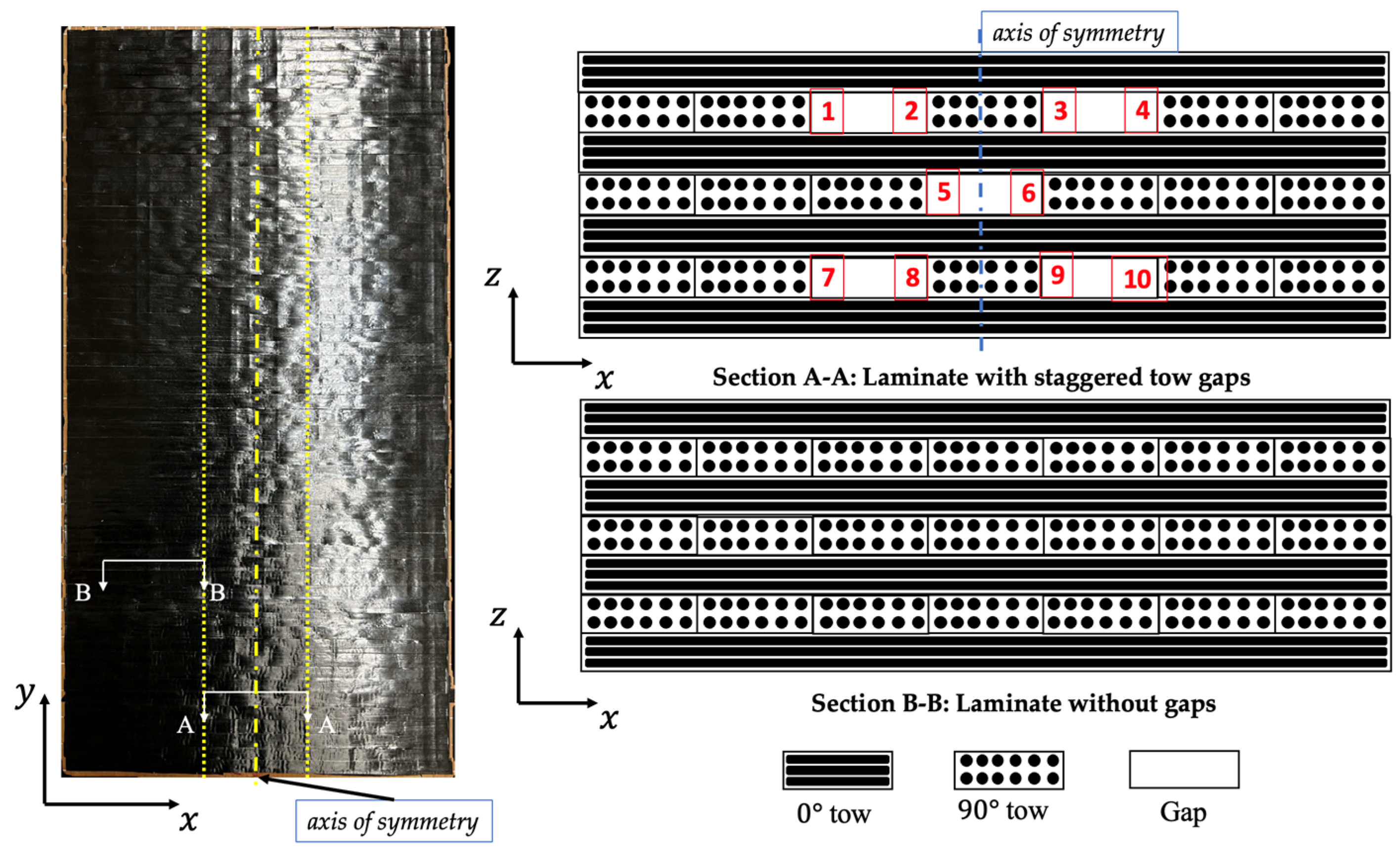

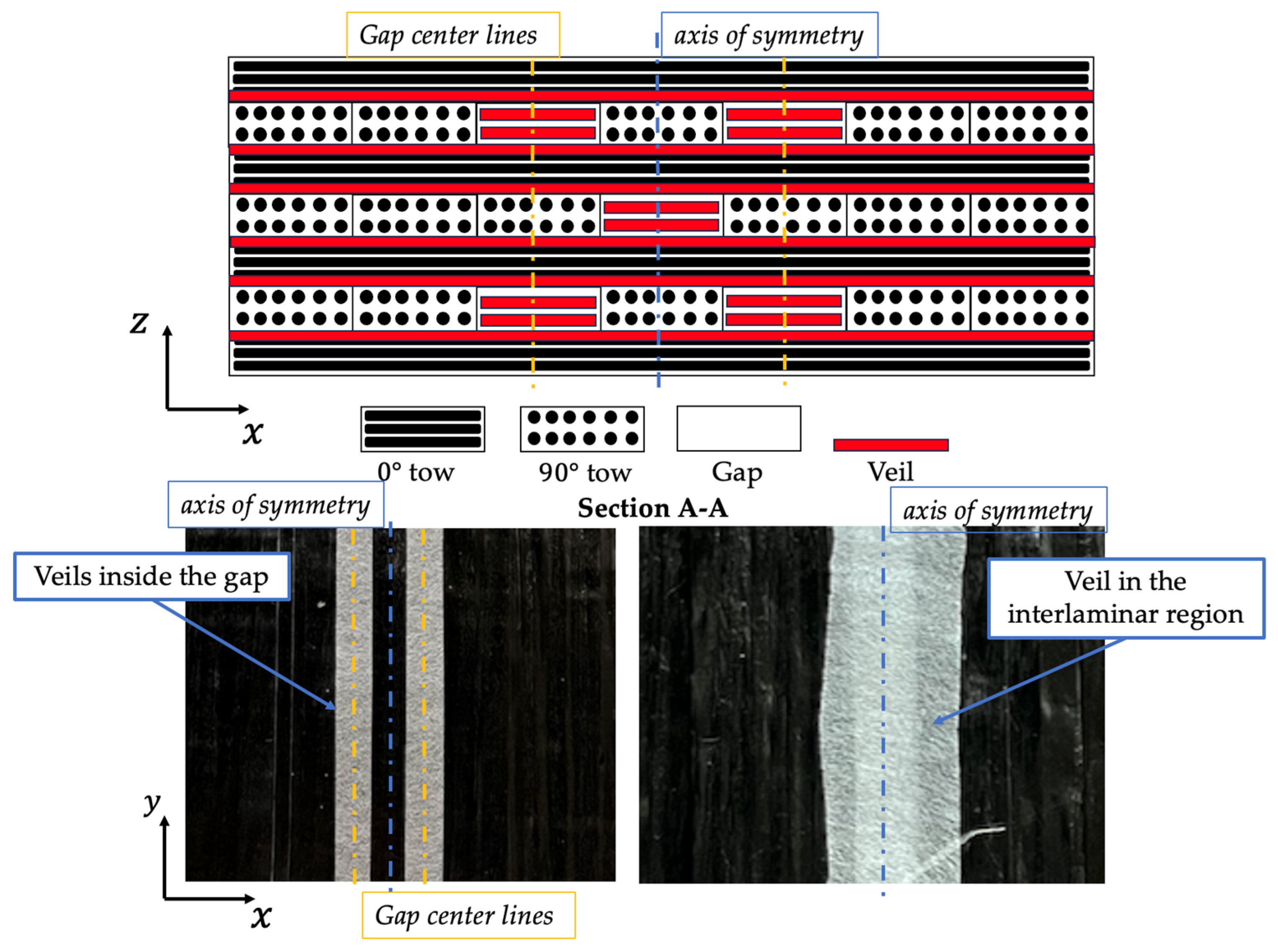

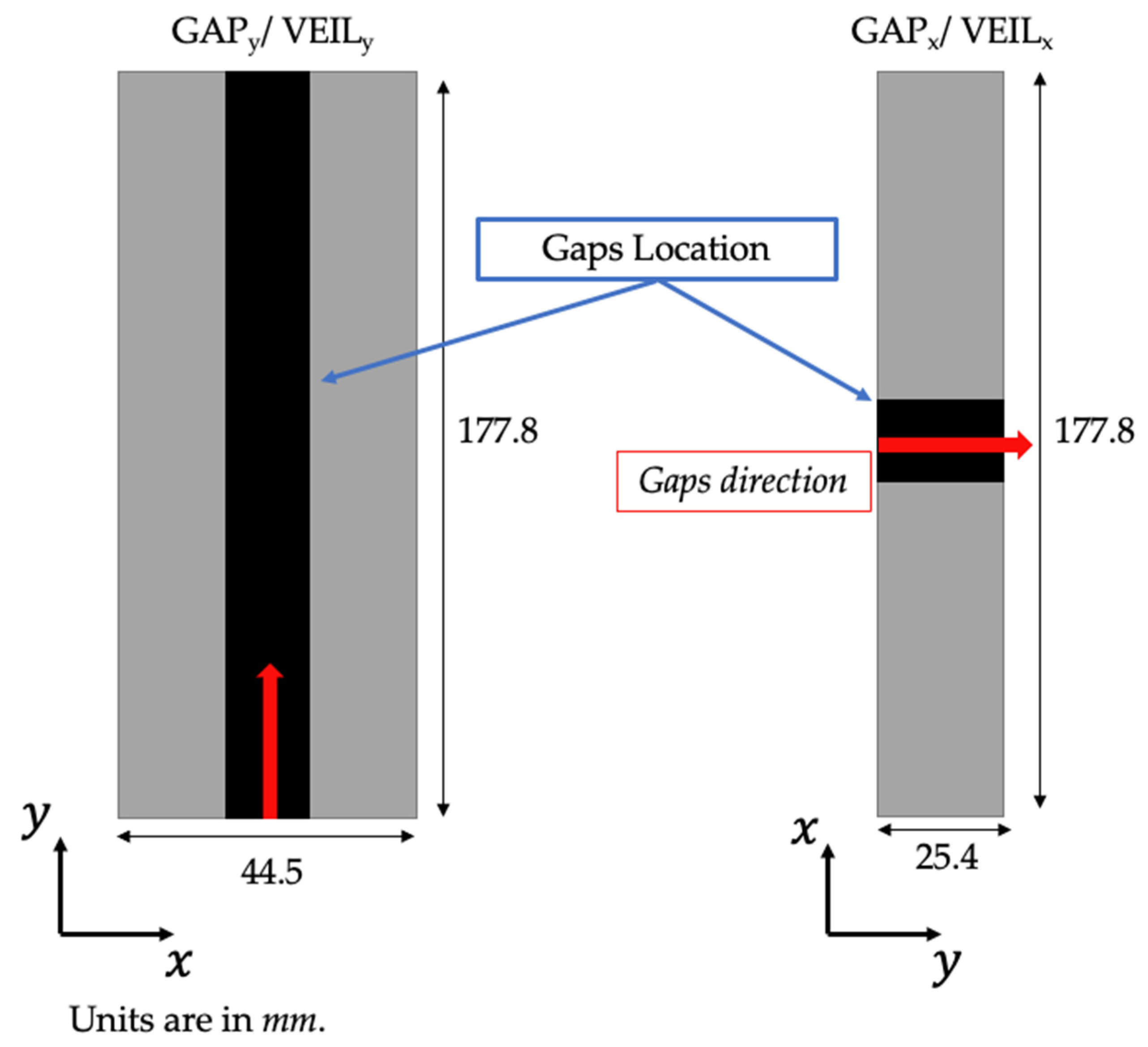

2.1. Materials and Sample Fabrication

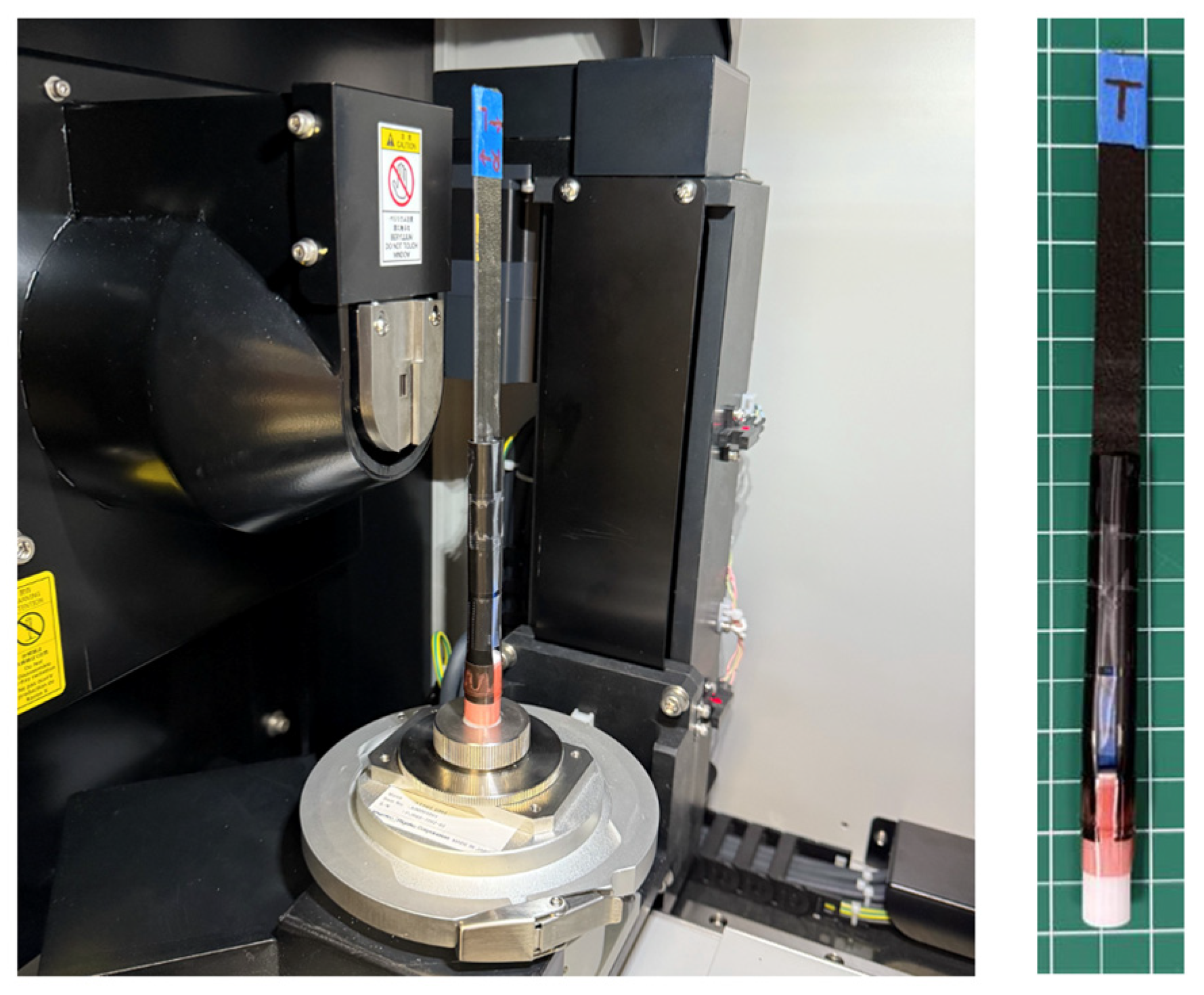

2.2. Micro-Computed Tomography

2.3. Mechanical Testing and Digital Image Correlation

2.4. Microscopy Analysis

2.5. Surface Profilometry

3. Modeling

3.1. Process Modeling Approach

3.2. PFA Modeling Approach

4. Results

4.1. Surface Profilometry

4.2. Microstructural Observations

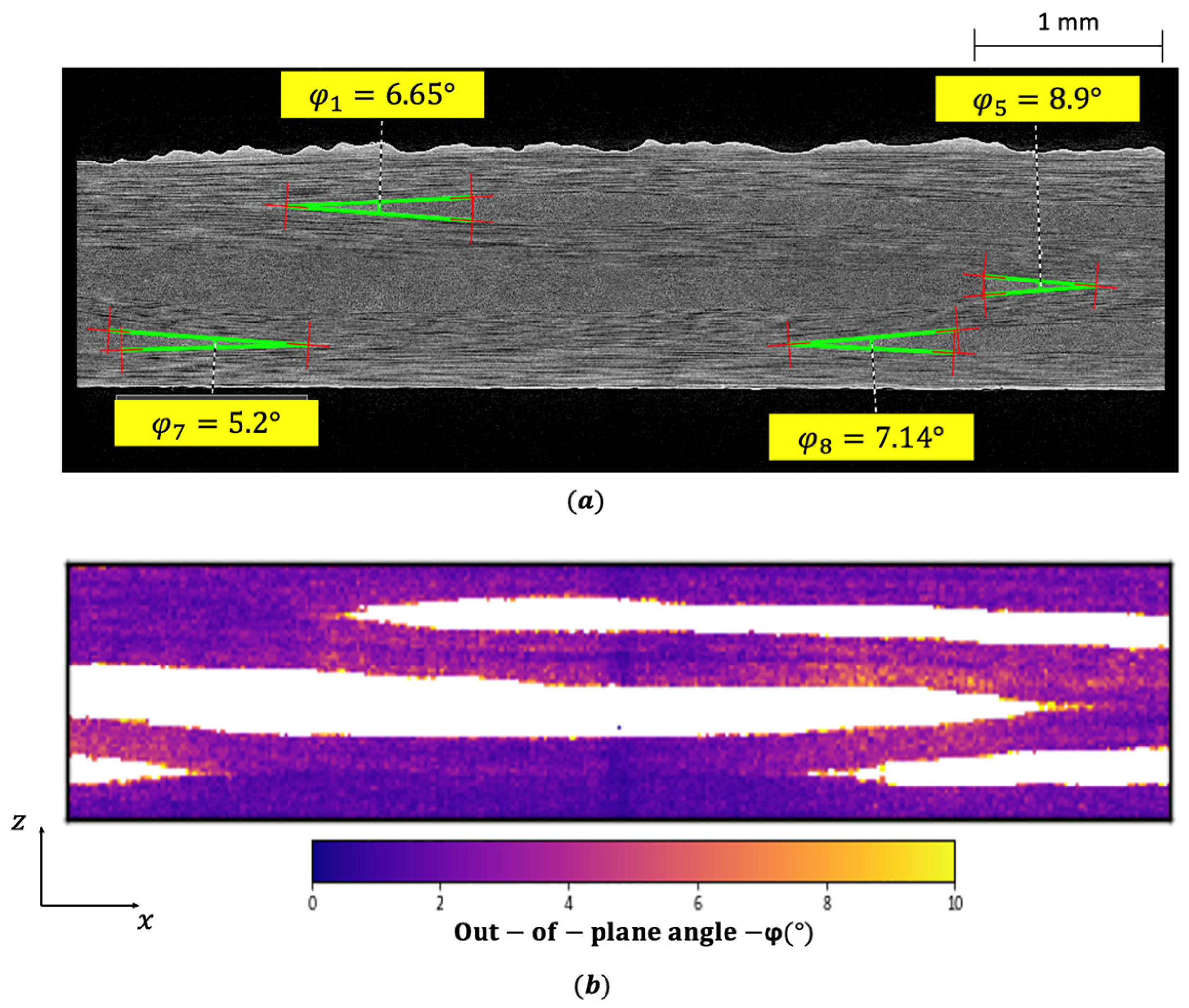

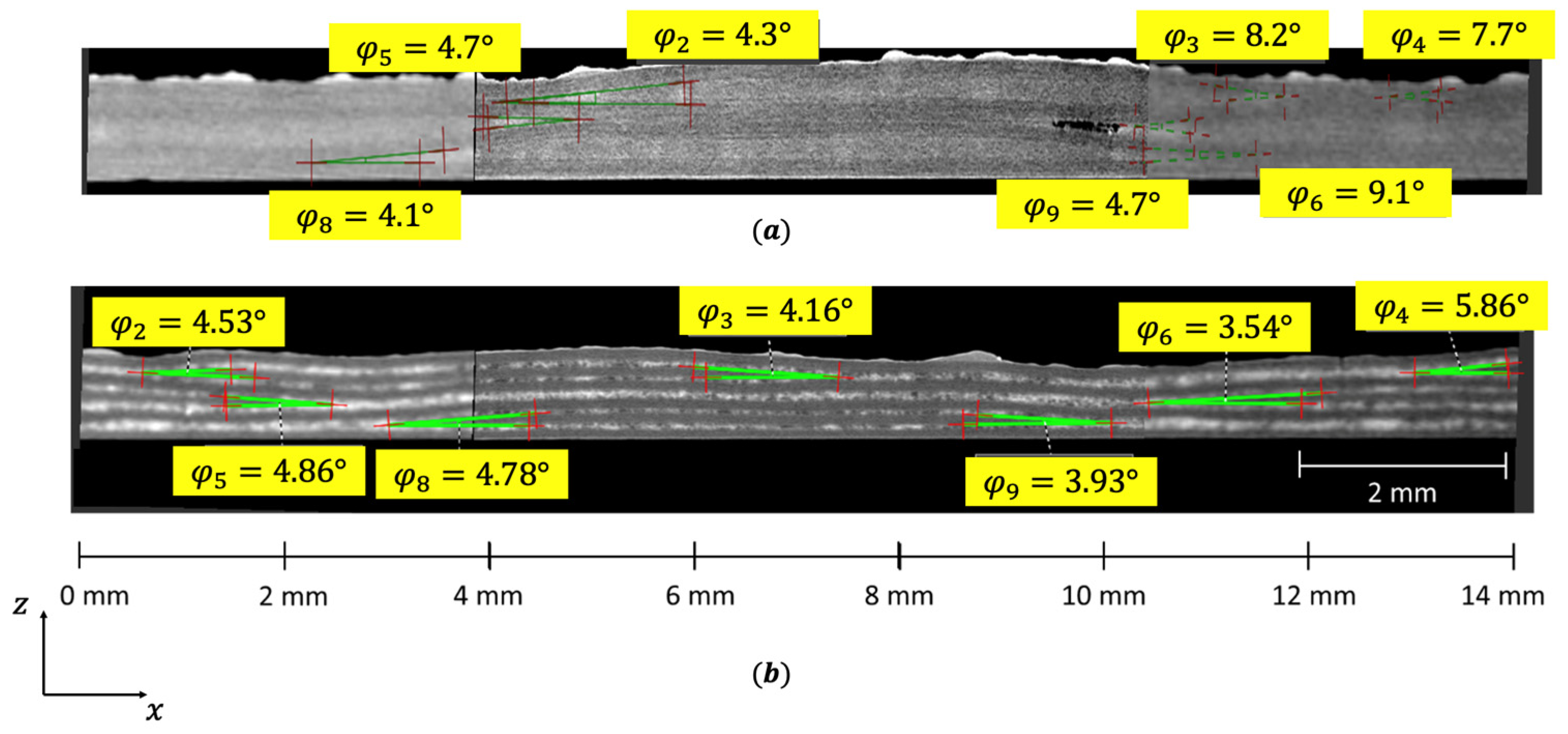

4.3. Internal Morphology Characterization via Micro-CT

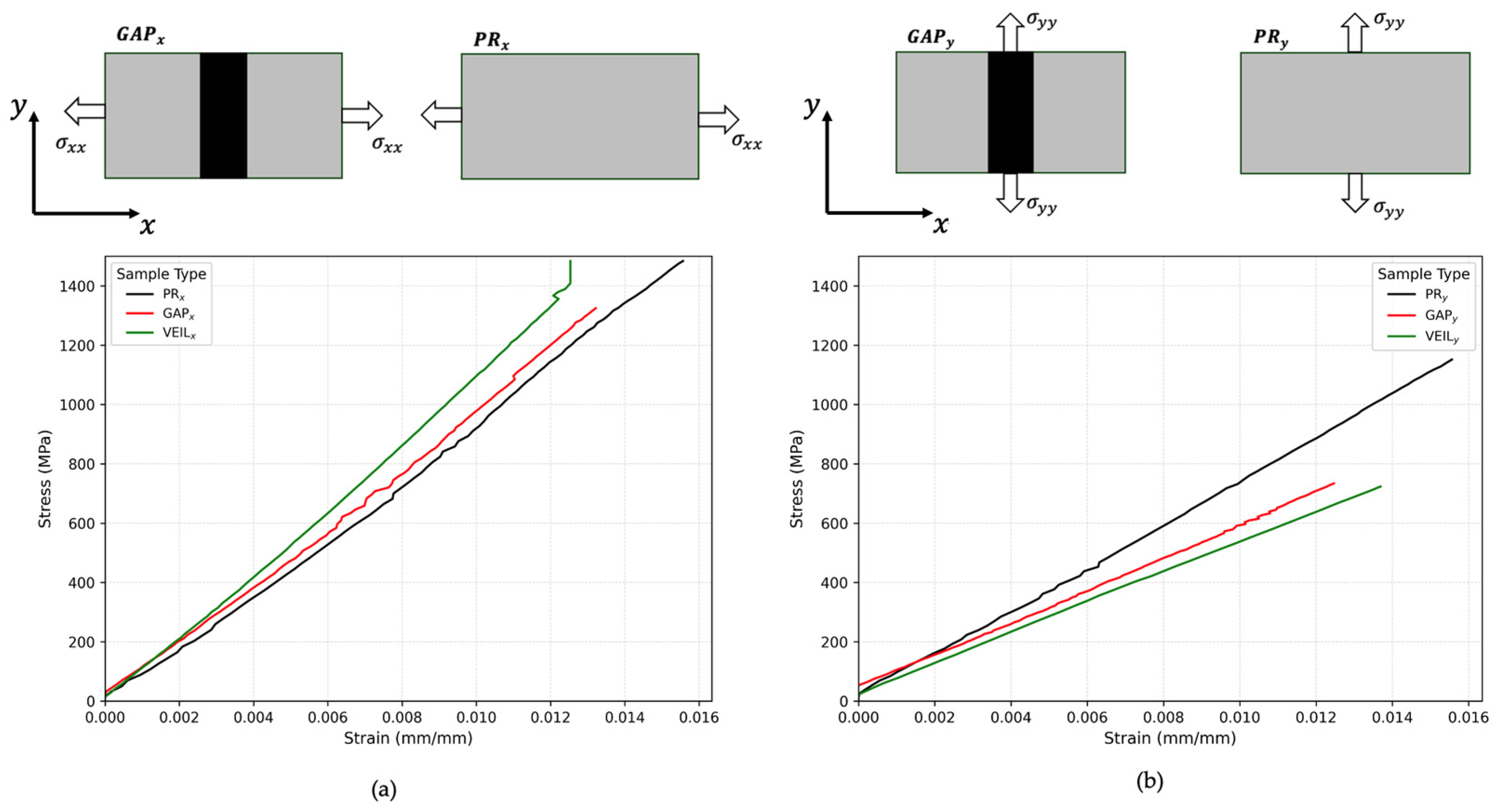

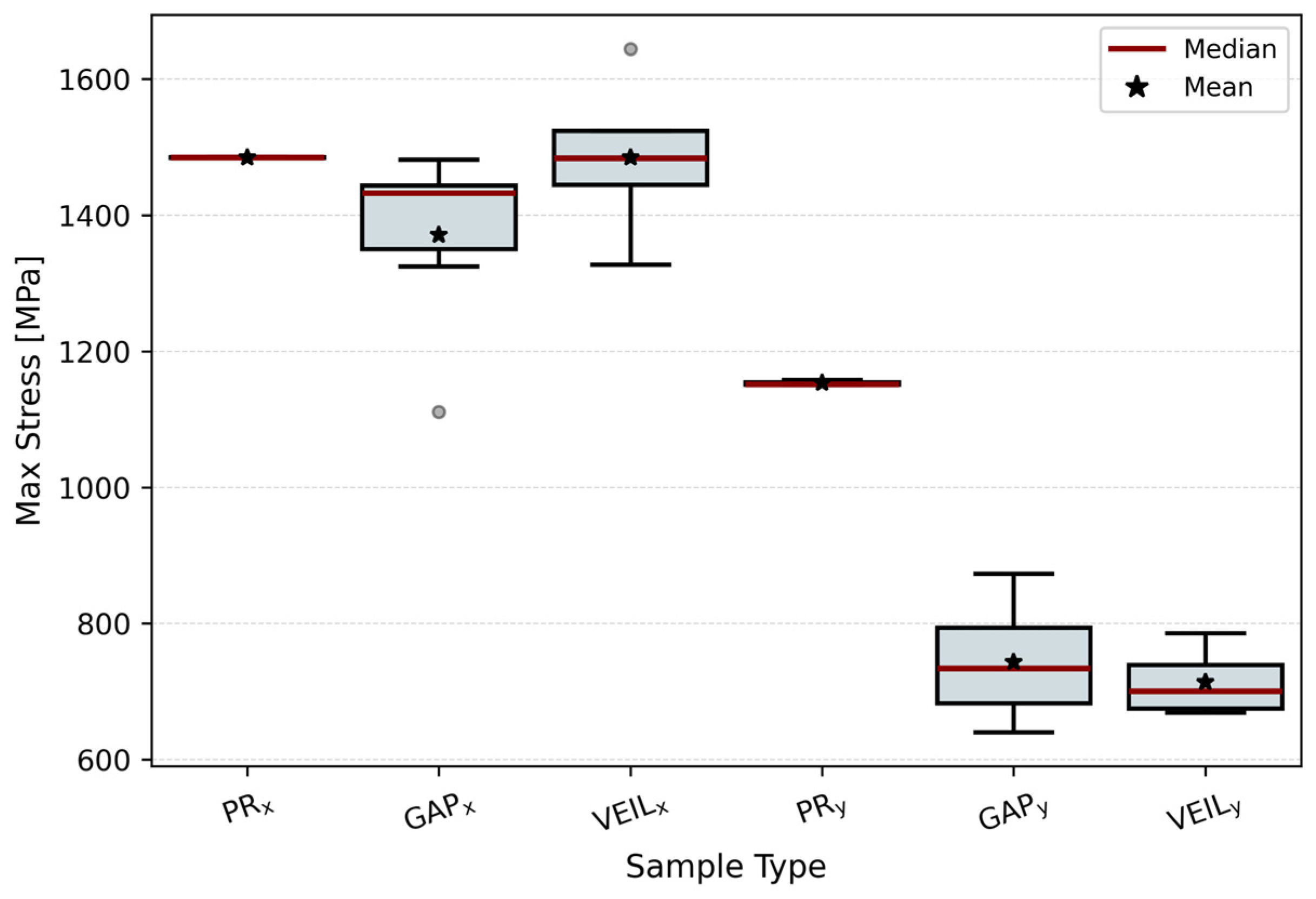

4.4. Tensile Testing

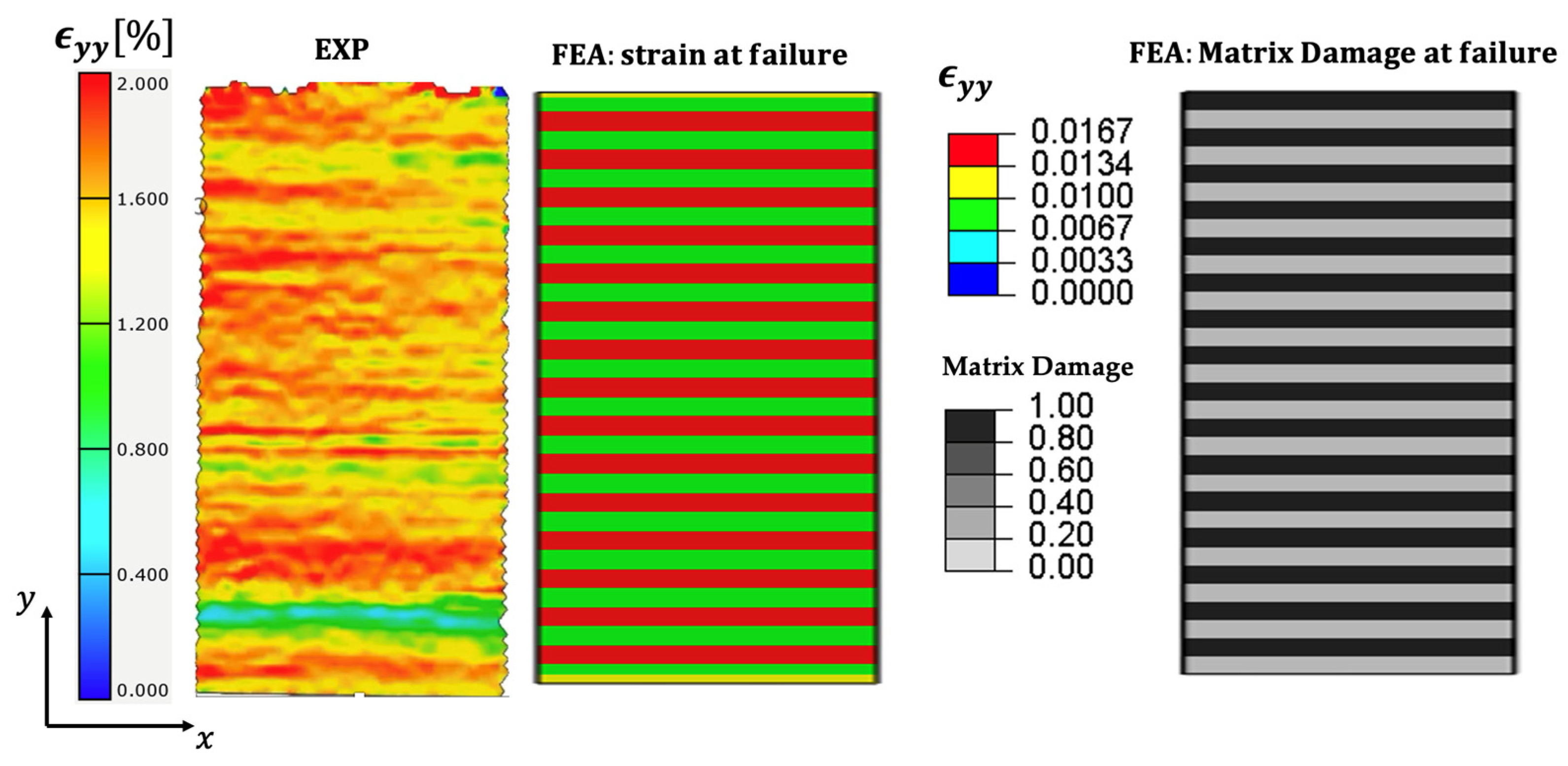

4.5. Strain Distribution Analysis Using DIC

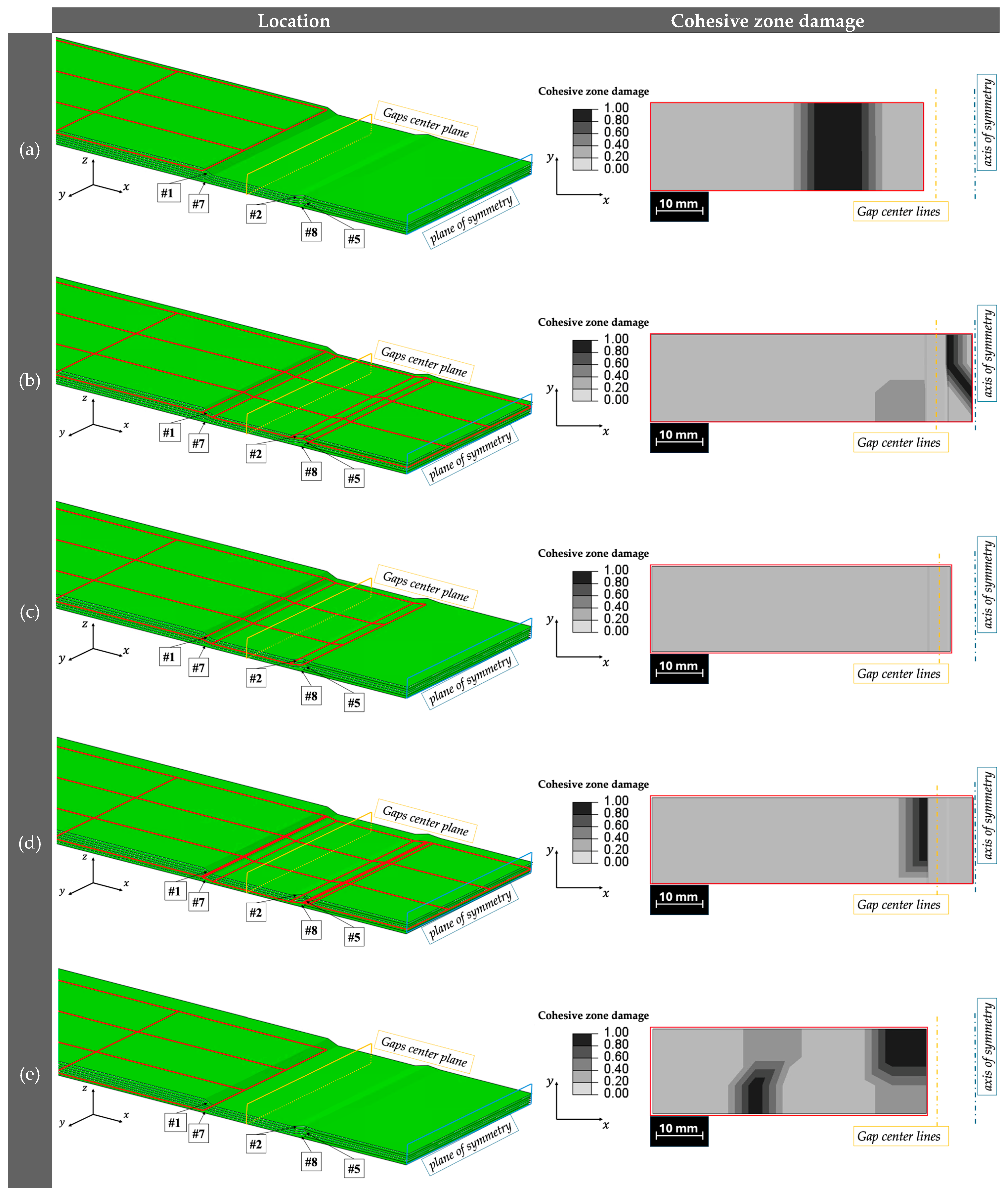

4.6. Analysis of Damage Modes from PFA Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Property | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Young’s modulus | 147,000 | (MPa) |

| Transverse Young’s modulus | 8700 | (MPa) |

| In-plane shear modulus | 5200 | (MPa) |

| Major Poisson ratio | 0.32 | |

| Minor Poisson ratio | 0.45 | |

| Transverse tensile strength | 80 | (MPa) |

| Shear strength | 98 | (MPa) |

| Mode I fracture toughness | 0.24 | ) |

| Mode II fracture toughness | 0.74 | ) |

| BK exponent for mode-mixity | 2.1 | |

| Transverse compressive strength | 288 | (MPa) |

| Fracture plane angle for pure transverse compression | 0.925 | (rad) |

| 3-direction Young’s modulus | 8700 | (MPa) |

| Shear modulus in 1-3 plane | 5200 | (MPa) |

| Shear modulus in 1-2 plane | 3000 | (MPa) |

| Poisson’s ratio in 2-3 plane | 0.32 | |

| Longitudinal tensile strength | 2600 | (MPa) |

| Longitudinal tensile strength ratio | 0.375 | |

| Longitudinal tensile fracture toughness | 35.90 | ) |

| Longitudinal tensile fracture toughness ratio | 0.75 | |

| Longitudinal compressive strength | 1700 | (MPa) |

| Longitudinal compressive strength ratio | 0.375 | |

| Longitudinal compressive fracture toughness | 10.68 | ) |

| Longitudinal fracture toughness ratio | 0.75 |

| Property | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Mode I strength | 80 | (MPa) |

| Mode II strength | 98 | (MPa) |

| Normal mode fracture energy | 0.24 | ) |

| Shear mode fracture energy | 0.74 | ) |

| B-K exponent | 2.1 |

References

- Lukaszewicz, D.H.-J.A.; Ward, C.; Potter, K.D. The Engineering Aspects of Automated Prepreg Layup: History, Present and Future. Compos. Part B Eng. 2012, 43, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chen, Z.C.; Shi, Y.; Mo, R. An Accurate Approach to Roller Path Generation for Robotic Fibre Placement of Free-form Surface Composites. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2014, 30, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinecke, F.; Willberg, C. Manufacturing-Induced Imperfections in Composite Parts Manufactured via Automated Fiber Placement. J. Compos. Sci. 2019, 3, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasington, A.; Sacco, C.; Halbritter, J.; Wehbe, R.; Harik, R. Automated Fiber Placement: A Review of History, Current Technologies, and Future Paths Forward. Compos. Part C Open Access 2021, 6, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayazbakhsh, K.; Arian Nik, M.; Pasini, D.; Lessard, L. Defect Layer Method to Capture Effect of Gaps and Overlaps in Variable Stiffness Laminates Made by Automated Fiber Placement. Compos. Struct. 2013, 97, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, M.; Cartié, D.; Davies, P.; Baley, C. Influence of Embedded Gap and Overlap Fiber Placement Defects on the Microstructure and Shear and Compression Properties of Carbon–Epoxy Laminates. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 82, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harik, R.; Saidy, C.; Williams, S.J.; Gurdal, Z.; Grimsley, B. Automated Fiber Placement Defect Identity Cards: Cause, Anticipation, Existence, Significance, and Progression. In Proceedings of the SAMPE 2018, Long Beach, CA, USA, 21–24 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsson, D.; Gutkin, R.; Edgren, F.; Asp, L.E. An Experimental Study of Fibre Waviness and Its Effects on Compressive Properties of Unidirectional NCF Composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 107, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.; Mali, K.D.; Singh, S. An Overview of the Formation of Fibre Waviness and Its Effect on the Mechanical Performance of Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 137, 106013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, E.Y.H.; Wang, W.C.; Christian, W.J.R. Experimental Study on the Effect of Waviness Defects on Composite Material Impact Dynamics. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 283, 111638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamora, V.C.; Rauch, V.; Kravchenko, S.G.; Kravchenko, O.G. Effect of Resin Bleed Out on Compaction Behavior of the Fiber Tow-gap Region during Automated Fiber Placement Manufacturing. Polymers 2023, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamora, V.C.C.; Kravchenko, O.; Kravchenko, S. Process Modeling of a Multidirectional Laminate with Multiple Embedded Staggered Tow-gaps. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2023 Forum, National Harbor, MD, USA, 23–27 January 2023; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: National Harbor, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Trochez, A.; Jamora, V.C.; Larson, R.; Wu, K.C.; Ghosh, D.; Kravchenko, O.G. Effects of Automated Fiber Placement Defects on High Strain Rate Compressive Response in Advanced Thermosetting Composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2021, 55, 4549–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghayoor, H.; Marsden, C.C.; Hoa, S.V.; Melro, A.R. Numerical Analysis of Resin-Rich Areas and Their Effects on Failure Initiation of Composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 117, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.S.; Summerscales, J.; James, M.N. Resin-Rich Volumes (RRV) and the Performance of Fibre-Reinforced Composites: A Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, H.; Yang, M.; Soghrati, S. Effect of Resin-Rich Zones on the Failure Response of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymers. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2020, 188–189, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rossi, D.; Cadran, V.; Thakur, P.; Palardy-Sim, M.; Lapalme, M.; Lessard, L. Experimental Investigation of the Effect of Half Gap/Half Overlap Defects on the Strength of Composite Structures Fabricated Using Automated Fibre Placement (AFP). Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2021, 150, 106610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marouene, A.; Legay, P.; Boukhili, R. Experimental and Numerical Investigation on the Open-Hole Compressive Strength of AFP Composites Containing Gaps and Overlaps. J. Compos. Mater. 2017, 51, 3631–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragoni, L.; Modenato, G.; De Rossi, N.; Vescovi, L.; Quaresimin, M. Effect of Fibre Waviness on the Compressive Fatigue Behavior of Woven Carbon/Epoxy Laminates. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 199, 108282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitohang, R.D.R.; Grouve, W.J.B.; Warnet, L.L.; Wijskamp, S.; Akkerman, R. The Relation between in-Plane Fiber Waviness Severity and First Ply Failure in Thermoplastic Composite Laminates. Compos. Struct. 2022, 289, 115374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitohang, R.D.R.; Grouve, W.J.B.; Warnet, L.L.; Akkerman, R. Effect of in-Plane Fiber Waviness Defects on the Compressive Properties of Quasi-Isotropic Thermoplastic Composites. Compos. Struct. 2021, 272, 114166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, A.; Gesell, P.; Drechsler, K. Strength Prediction of Ply Waviness in Composite Materials Considering Matrix Dominated Effects. Compos. Struct. 2015, 127, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Potter, K.D.; Etches, J. Experimental Investigation and Characterisation Techniques of Compressive Fatigue Failure of Composites with Fibre Waviness at Ply Drops. Compos. Struct. 2013, 100, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Akbolat, M.Ç.; Katnam, K.B.; Zou, Z.; Potluri, P.; Taylor, J. On the Interlaminar Fracture Behavior of Carbon/Epoxy Laminates Interleaved with Fiber-Hybrid Non-Woven Veils. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 3315–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwata, M.; Hogg, P.J. Interlaminar Toughness of Interleaved CFRP Using Non-Woven Veils: Part 1. Mode-I Testing. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwata, M.; Hogg, P.J. Interlaminar Toughness of Interleaved CFRP Using Non-Woven Veils: Part 2. Mode-II Testing. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 1560–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, D.; Bologna, F.; Scarselli, G.; Ivankovic, A.; Murphy, N. Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of Aerospace-Grade Carbon Fibre Reinforced Plastics Interleaved with Thermoplastic Veils. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 128, 105642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautmann, M.; Gabriel, E.R.; Kim, B.C. Advanced Continuous Tow Shearing Process Utilising in-Line Tow Width Control in Fibre Steering. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 196, 109025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, G. Mechanical Characterization of Stretch Broken Carbon Fiber Materials—IM7 Fiber in 8552 Resin. In Proceedings of the SAMPE’10 Spring Symposium Technical Conference Proceedings, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 17–20 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hexcel. HexPly® 8552 Product Data Sheet; Hexcel Composites: Cambridge, UK; Hexcel Corporation: Stamford, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bergan, A.C. New Developments in the CompDam Fiber Kinking Model for the Interaction of Kinking and Splitting Cracks with Application to Open Hole Compression Specimens. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2021 Forum, Nashville, TN, USA, 1–15 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, F.A.; Bergan, A.C.; Dávila, C.G. CompDam—Deformation Gradient Decomposition (DGD), v2.5.0 [Software]. NASA. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/nasa/CompDam_DGD (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Leone, F.A., Jr. Deformation Gradient Tensor Decomposition for Representing Matrix Cracks in Fiber-Reinforced Materials. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2015, 76, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassapoglou, C. Design and Analysis of Composite Structures: With Applications to Aerospace Structures; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gyekenyesi, A.L. Crack Development in Cross-Ply Laminates Under Uniaxial Tension; NASA Contractor Report 195464; Prepared for NASA Lewis Research Center under Grant NAG3-1543, January; Cleveland State University: Cleveland, OH, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nairn, J.A. Matrix Microcracking in Composites. In Comprehensive Composite Materials; Kelly, A., Zweben, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R.; Bergan, A.; Leone, F.; Kravchenko, O.G. Influence of Stochastic Adhesive Porosity and Material Variability on Failure Behavior of Adhesively Bonded Composite Sandwich Joints. Compos. Struct. 2023, 306, 116608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ravangard, A.; Celebi, K.; Kravchenko, S.G.; Kravchenko, O.G. Mitigating Out-of-Plane Fiber Waviness in AFP Laminates with Tow-Gaps via Selective Placement of Thermoplastic Veils. Fibers 2025, 13, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib13110145

Ravangard A, Celebi K, Kravchenko SG, Kravchenko OG. Mitigating Out-of-Plane Fiber Waviness in AFP Laminates with Tow-Gaps via Selective Placement of Thermoplastic Veils. Fibers. 2025; 13(11):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib13110145

Chicago/Turabian StyleRavangard, Ahmadreza, Kuthan Celebi, Sergii G. Kravchenko, and Oleksandr G. Kravchenko. 2025. "Mitigating Out-of-Plane Fiber Waviness in AFP Laminates with Tow-Gaps via Selective Placement of Thermoplastic Veils" Fibers 13, no. 11: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib13110145

APA StyleRavangard, A., Celebi, K., Kravchenko, S. G., & Kravchenko, O. G. (2025). Mitigating Out-of-Plane Fiber Waviness in AFP Laminates with Tow-Gaps via Selective Placement of Thermoplastic Veils. Fibers, 13(11), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib13110145