Effect of CeO2 on Microstructure and Properties of Cr3C2/Fe-Based Composite Coatings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

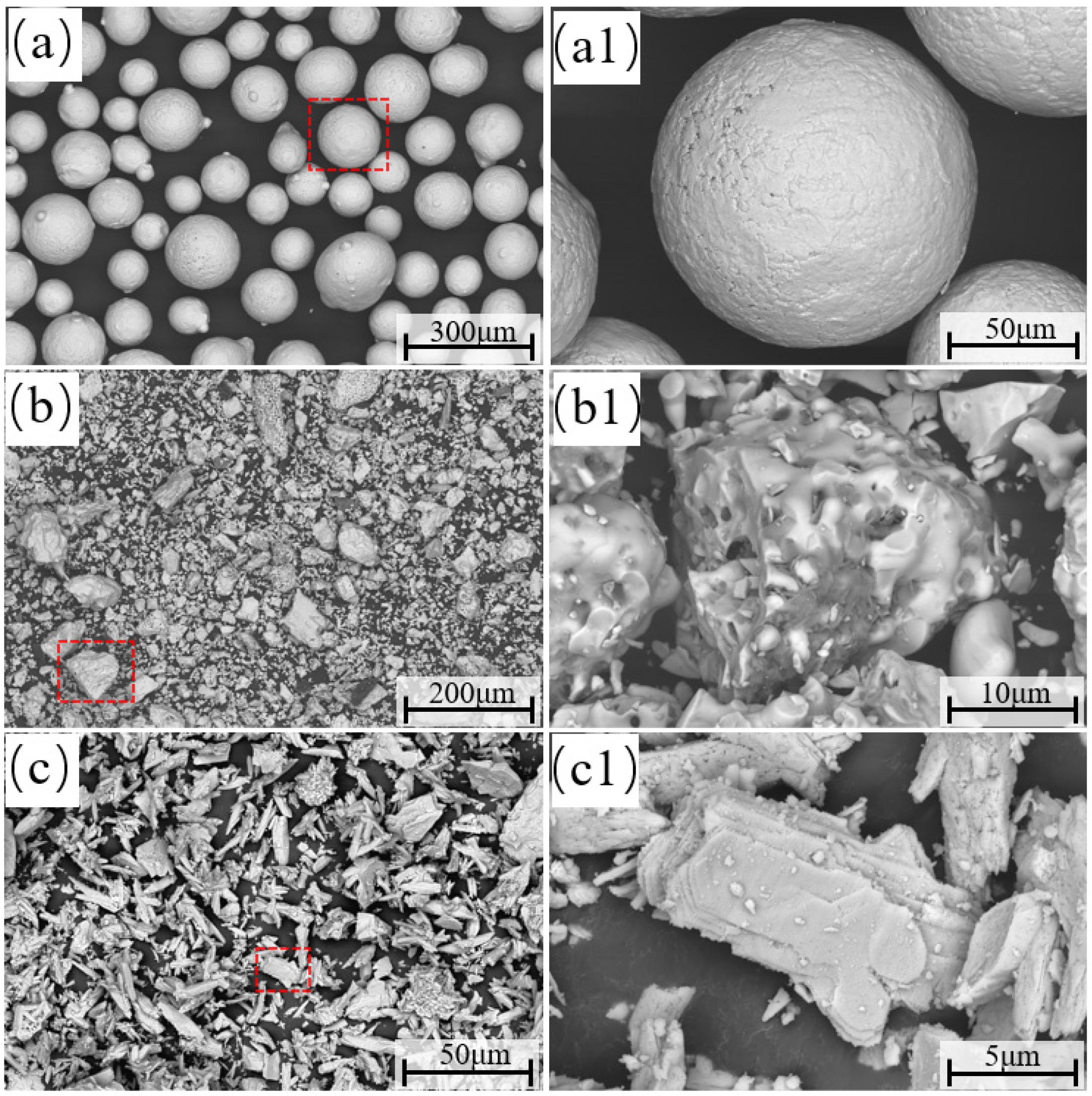

2.1. Experimental Materials

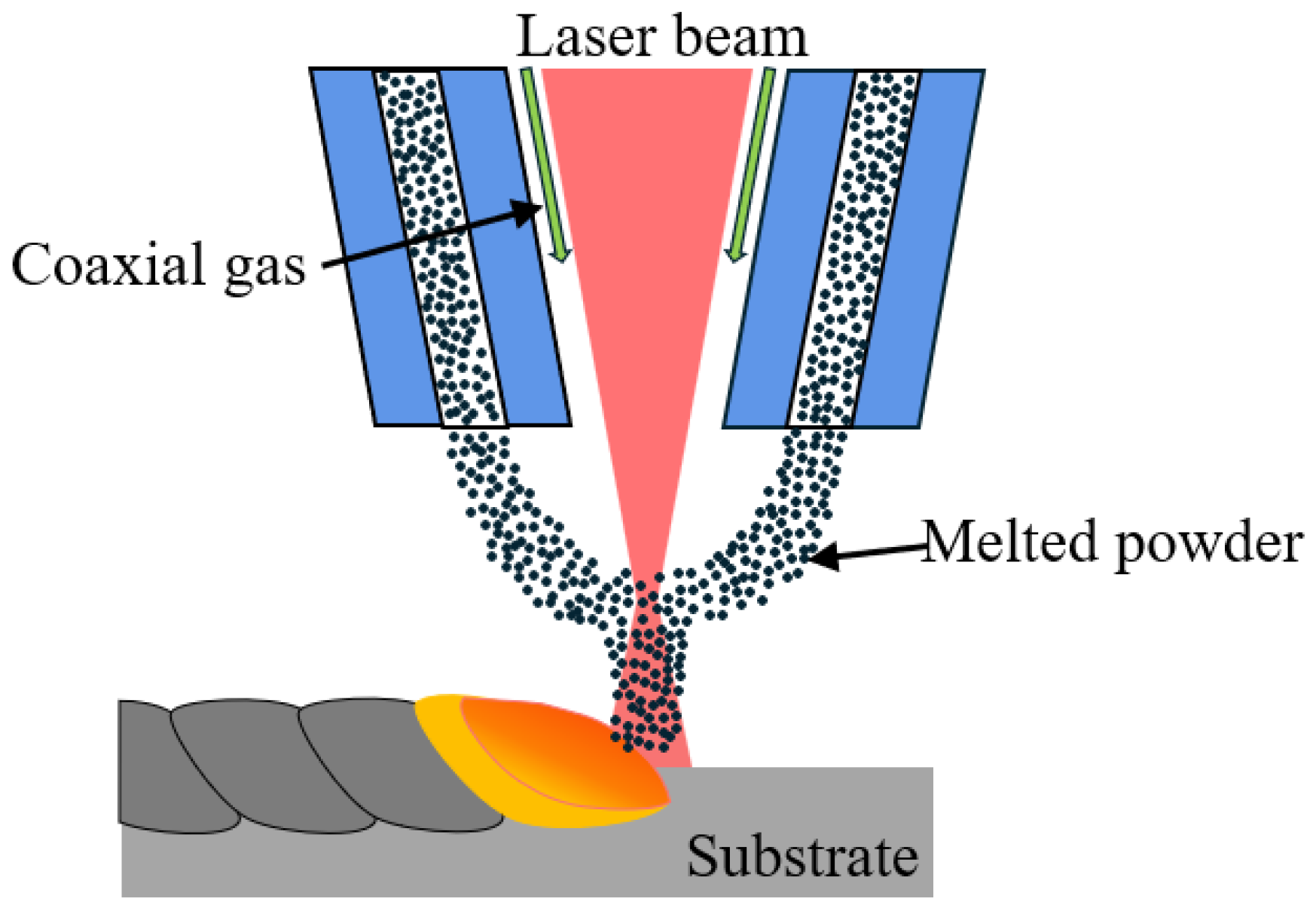

2.2. Coating Preparation

2.3. Performance Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

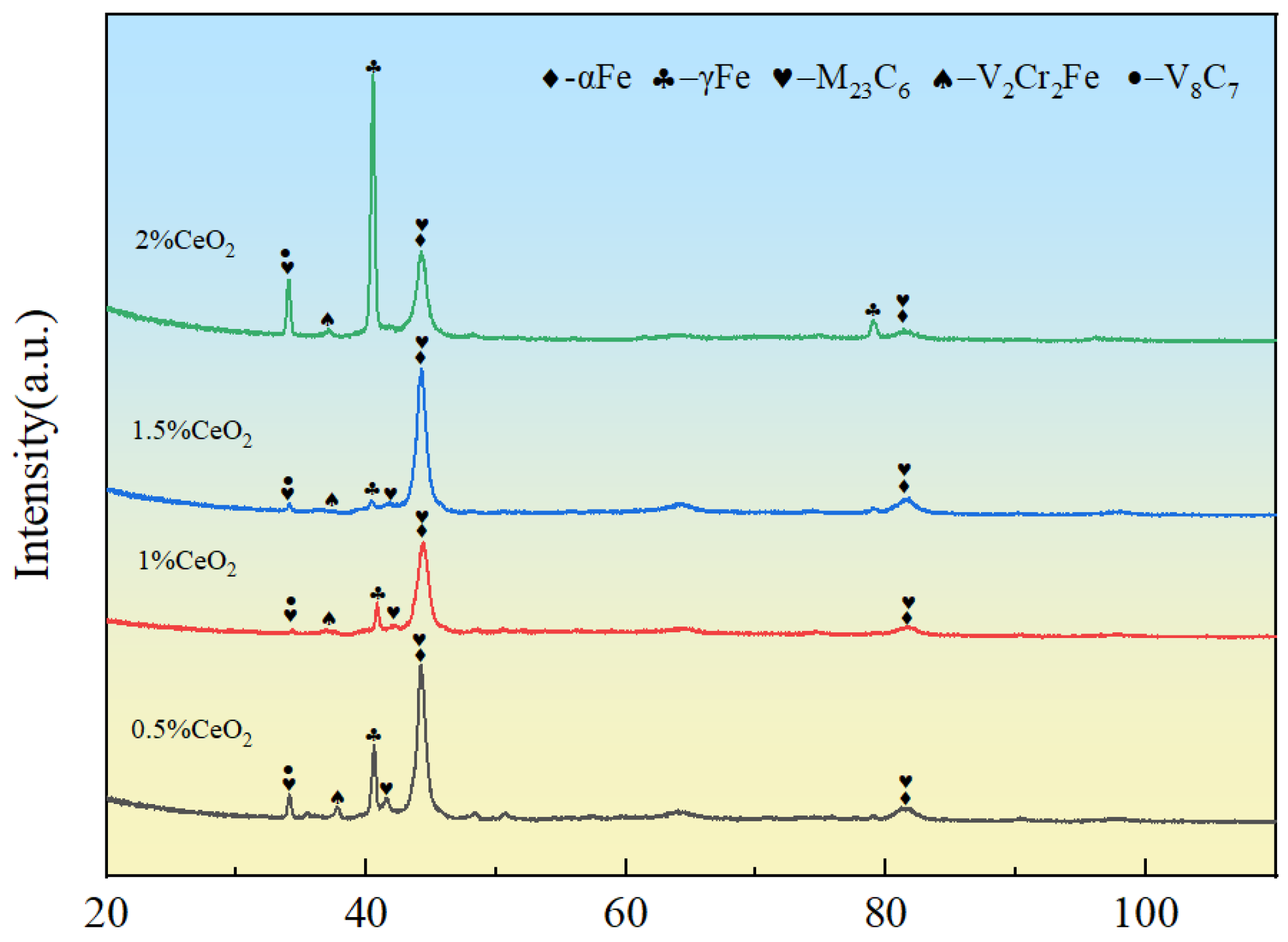

3.1. Phase Composition

3.2. Microscopic Structure

3.3. Microhardness

3.4. Wear Resistance

3.4.1. Friction Coefficient and Wear Rate

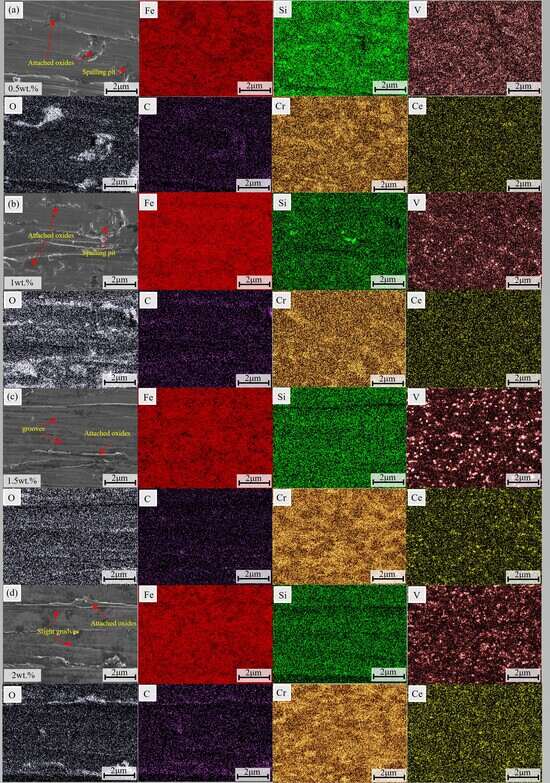

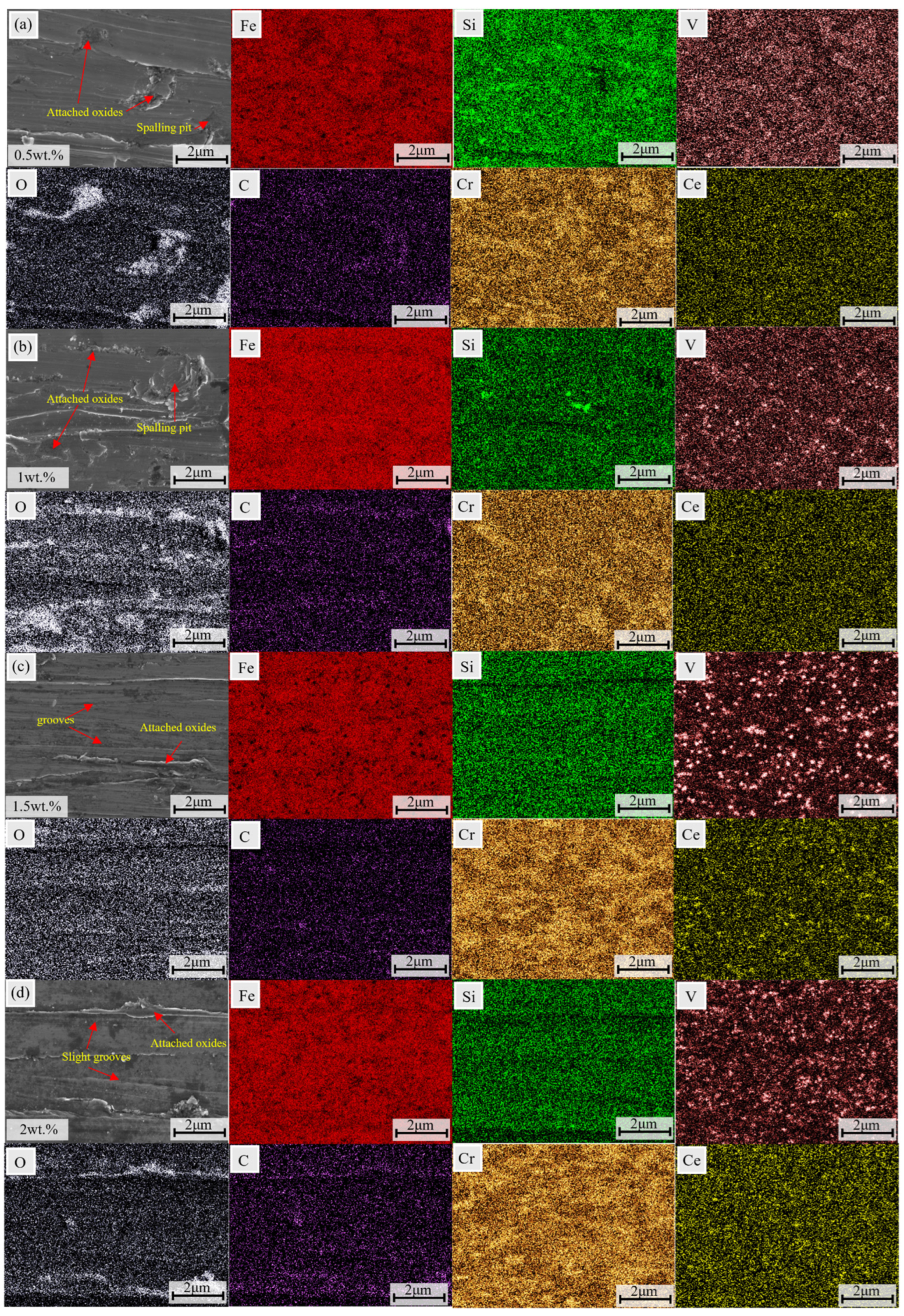

3.4.2. Worn Surface Morphology

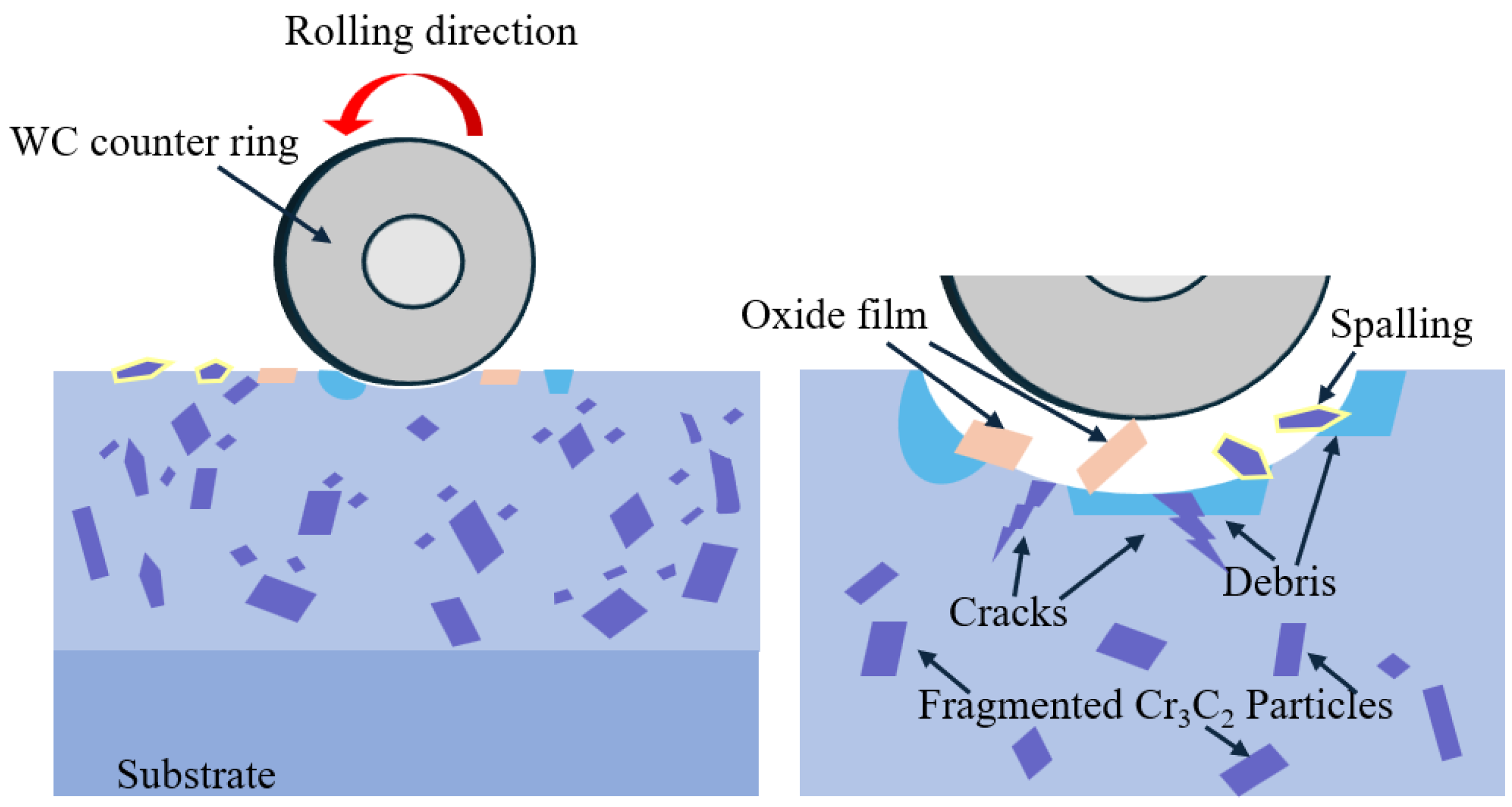

3.4.3. Wear Mechanism

3.5. Corrosion Resistance

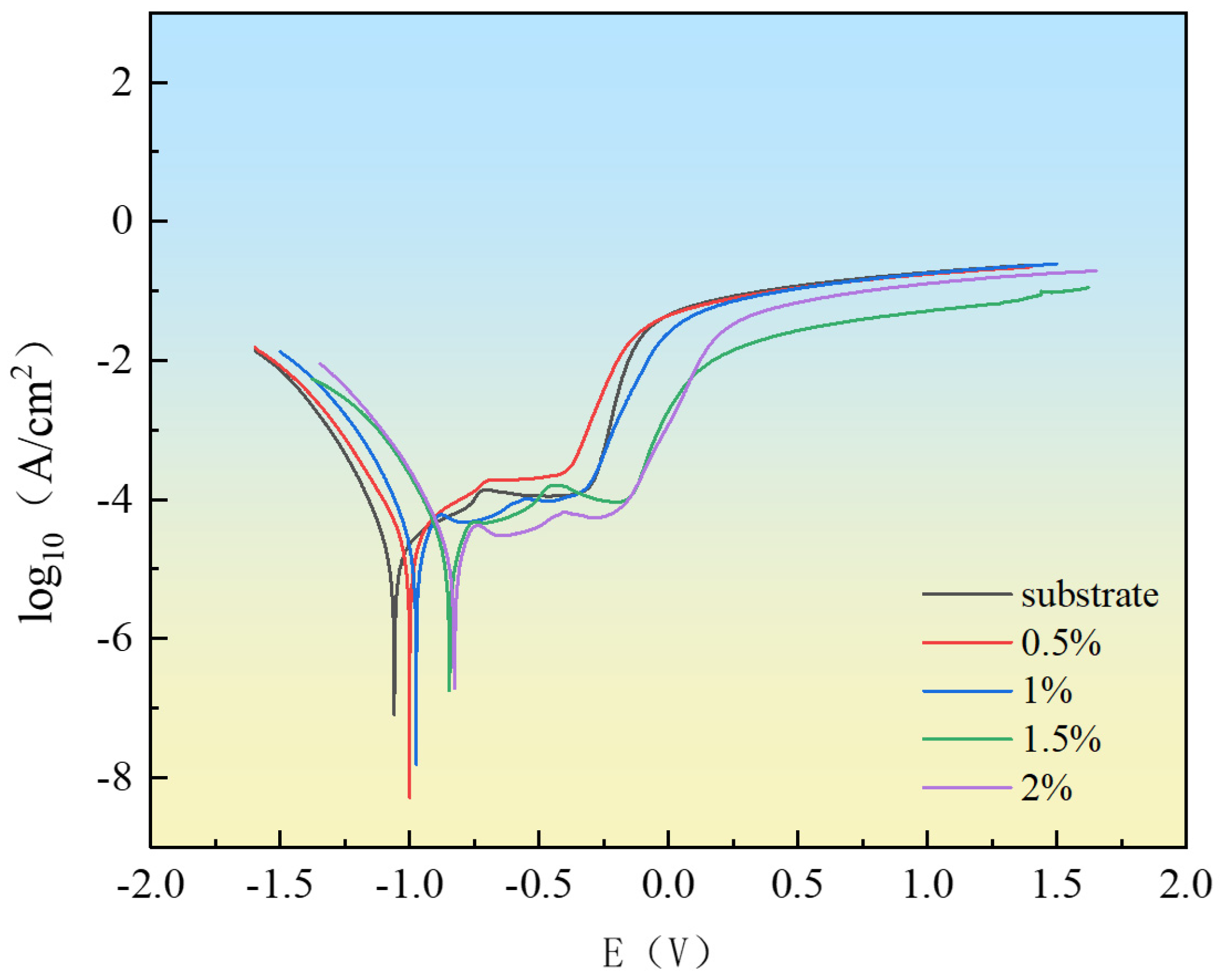

3.5.1. Polarization Curves

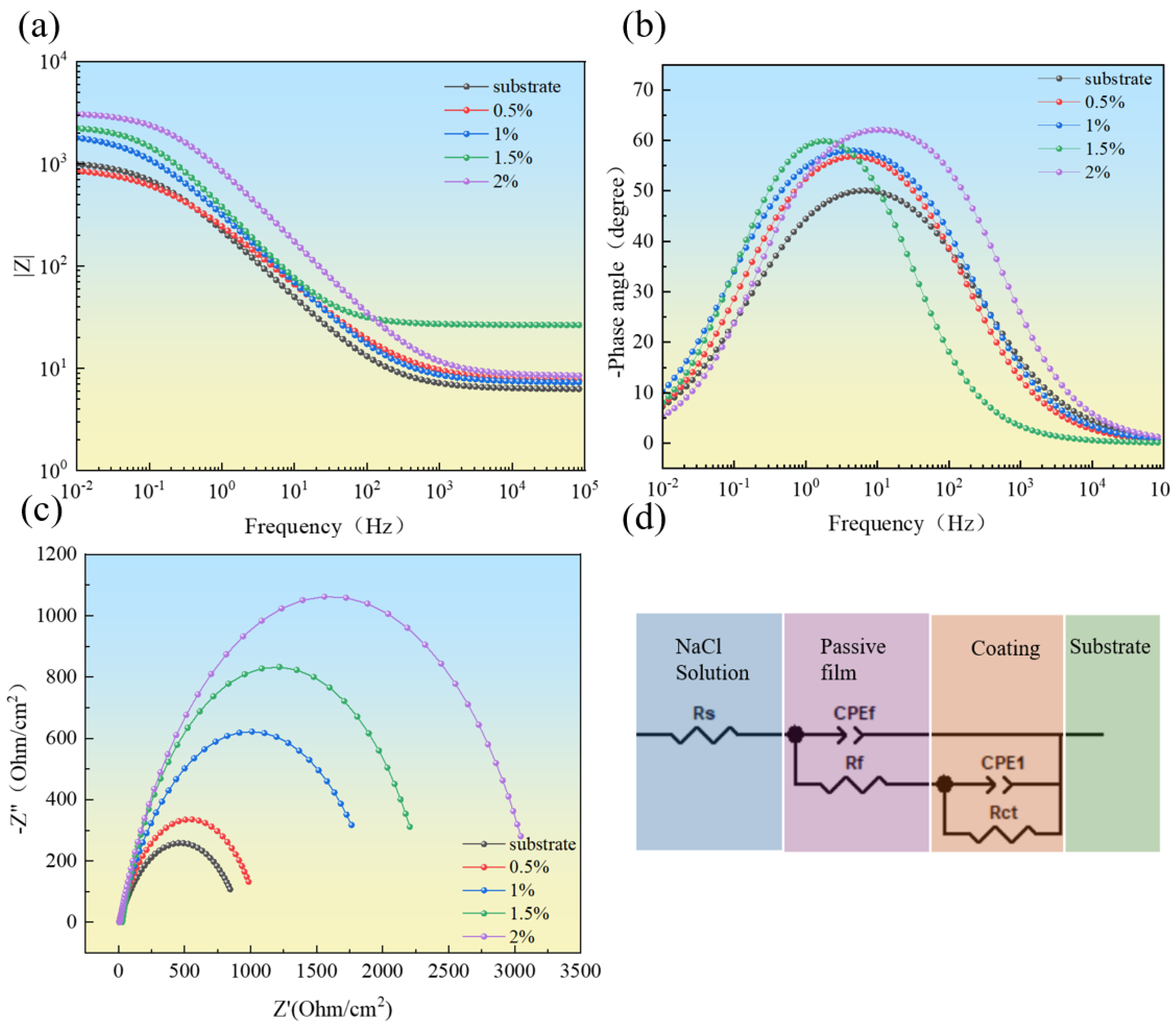

3.5.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

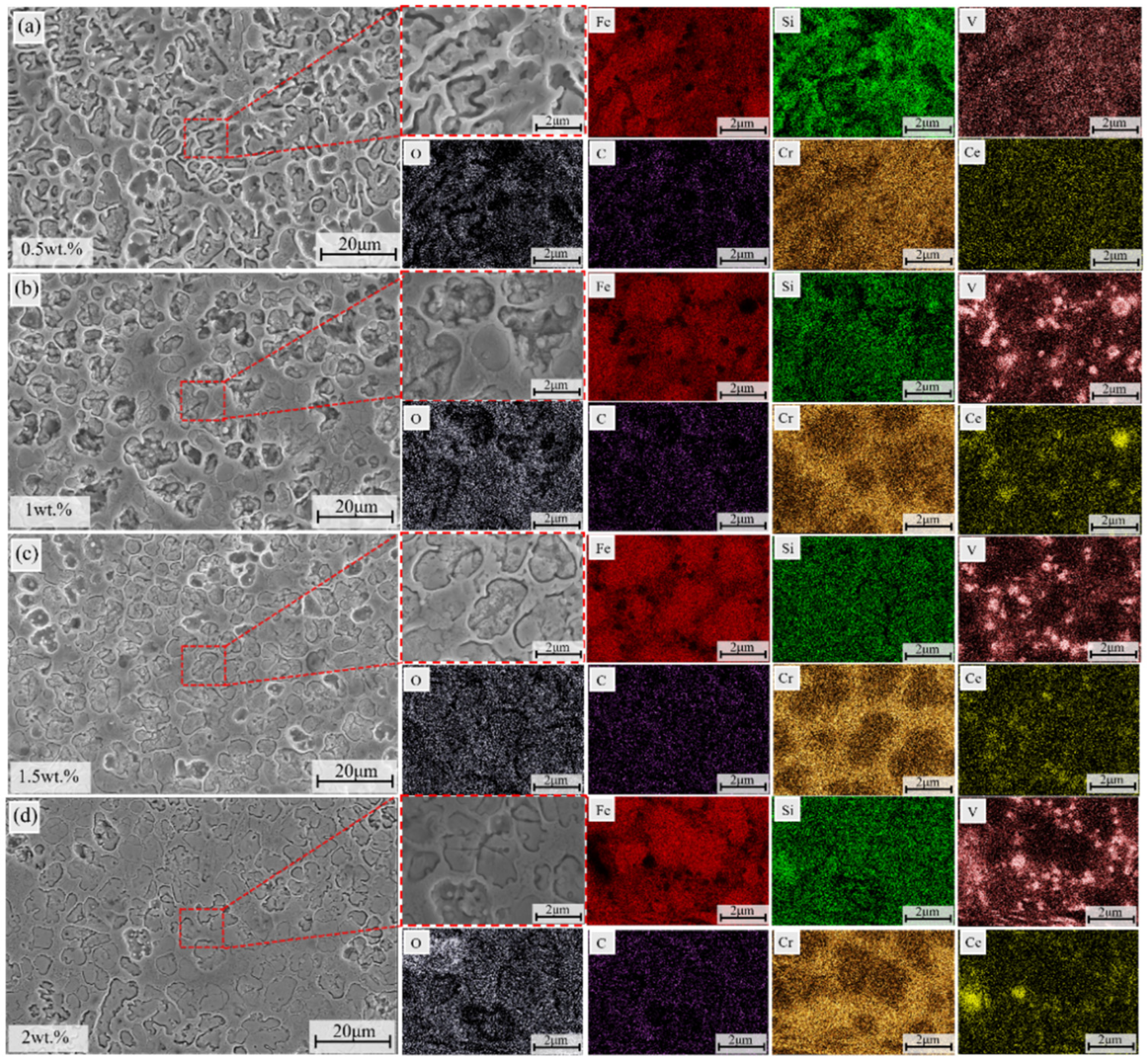

3.5.3. Corrosion Morphology

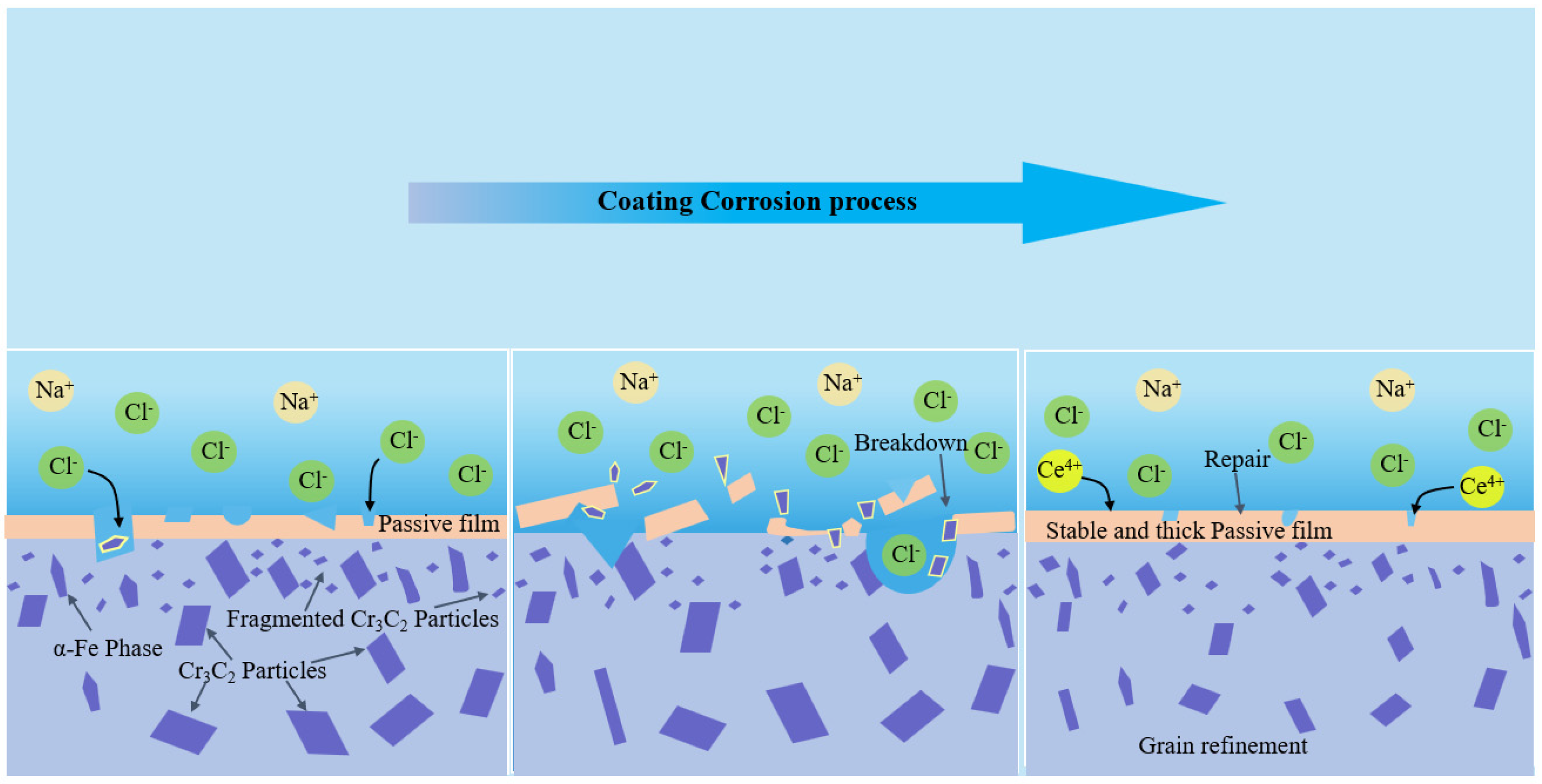

3.5.4. Corrosion Mechanism

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The addition of CeO2 did not alter the fundamental phase composition of the coating, which remained composed of α-Fe, M23C6, and vanadium carbides. Through mechanisms such as heterogeneous nucleation and grain boundary pinning, Ce promoted the transformation of coarse dendritic grains into fine equiaxed grains. When the CeO2 content reached 2 wt.%, all grains in the coating were transformed into fine equiaxed grains.

- (2)

- With the increase in CeO2 content, the dendritic structure was significantly refined, and the number of grain boundaries increased, which hindered dislocation movement. Simultaneously, CeO2 facilitated the dispersion of hard carbide phases, enhancing the second-phase strengthening effect. Consequently, the microhardness and wear resistance of the coatings were substantially improved. The coating containing 2 wt.% CeO2 exhibited the highest microhardness (923.08 HV0.5, 4.56 times higher than that of the substrate), the lowest friction coefficient (0.31), and the minimum wear rate (2.0 × 10−3 mm3/(N·m)).

- (3)

- CeO2 was able to significantly enhance the corrosion resistance of the coatings. In a 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution, the 2 wt.% CeO2 coating demonstrated the optimal corrosion resistance, with a corrosion potential of −0.82 V and a corrosion current density of 2.04 × 10−6 A/cm2. This was primarily attributed to the ability of CeO2 to refine grains, inhibit the formation of coarse carbides to alleviate micro-galvanic corrosion, and promote the formation of a dense passive film with self-healing capabilities to block Cl− intrusion.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gómez de León Hijes, F.C.; Sánchez Robles, J.; Martínez García, F.M.; García, M.A. Dynamic management of periodicity between measurements in predictive maintenance. Measurement 2023, 213, 112721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorko, G.; Liptai, P.; Molnár, V. Proposal of the methodology for noise sources identification and analysis of continuous transport systems using an acoustic camera. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2018, 83, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, B.; Ma, H.; Xia, R.; Wang, X.; Cui, W.; Zhang, P.; Jiao, H. Design and evaluation of abrasive wear testing device for scraper conveyor middle plates. Powder Technol. 2025, 460, 121042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Liu, Z.; Bi, W.; Wei, X. Study on the mechanical effect and wear behaviour of middle trough of a scraper conveyor based on DEM MBD. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2022, 236, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Song, G.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Hao, J. Energy consumption optimization of scraper conveyors adopting rolling friction: A technological revolution in China’s coal mining equipment. J. Ind. Saf. 2025, 2, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.Y.; Zhu, Z.C. Study on wear behavior of middle plate during material transportation of scraper conveyor under composite working conditions. Tribol. Trans. 2017, 37, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.P. Research on application of diamond-coated wear-resistant plates in middle trough repair of scraper conveyors. Coal Chem. Ind. 2025, 48, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.Y.; Zhu, Z.C. Case study: Wear analysis of the middle plate of a heavy-load scraper conveyor chute under a range of operating conditions. Wear 2017, 380–381, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryba, T.; Bzinkowski, D.; Siemiątkowski, Z.; Rucki, M.; Stawarz, S.; Caban, J.; Samociuk, W. Monitoring of Rubber Belt Material Performance and Damage. Materials 2024, 17, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Xue, P.; Lan, Q.; Meng, G.; Ren, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xu, P.; Liu, Z. Recent research and development status of laser cladding: A review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 138, 106915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Ren, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X. Effect of process parameters on microstructure and tribological properties of Ni60A/Cr3C2 laser cladding on 60Si2Mn steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 473, 130005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdi, D.; Garrido, M.A.; Múnez, C.J.; Poza, P. Cr3C2 incorporation into an Inconel 625 laser cladded coating: Effects on matrix microstructure, mechanical properties and local scratch resistance. Mater. Des. 2015, 67, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdi, D.; Garrido, M.A.; Múnez, C.J.; Poza, P. Microscale effect of high-temperature exposition on laser cladded Inconel 625-Cr3C2 metal matrix composite. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 695, 2696–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, G.; Gao, W.; Chen, C.; Huang, X.; Feng, M. Review on hard particle reinforced laser cladding high-entropy alloy coatings. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 1366–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Jiang, W.; Xu, K.; Wen, X.; Huang, B. Microhardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance of AlCoCrFeNi2.1+xCeO2 high-entropy alloy coatings by laser cladding. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 43, 111662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kovacevic, R.; Liu, J. Mechanism of surface modification of CeO2 in laser remelted alloy spray coatings. Wear 1998, 221, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C. Effect of nano-CeO2 on microstructure properties of TiC/TiN+nTi(CN) reinforced composite coating. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2012, 35, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.H. Study on High-Temperature Tribological Characteristics and Mechanism of Multicomponent Alloy Coatings Doped by Rare Earth Ce. Ph.D. Thesis, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, Q. Microstructure and properties of the low-power-laser clad coatings on magnesium alloy with different amount of rare earth addition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 353, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zou, Y.; Zou, Z.; Shi, C. Effects of CeO2 on microstructure and corrosion resistance of TiC-VC reinforced Fe-based laser cladding layers. J. Rare Earths 2014, 32, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Li, M.Y.; Wang, Y. Microstructure and wear resistance of laser clad Fe-Cr3C2 composite coating on 35CrMo steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2013, 22, 3749–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Chai, C.; Hu, S.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Yi, J.; Yu, J.; Eckert, J. Effects of nano-CeO2 particles on the microstructural evolution and tribological performance of laser-deposited Ni45 coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 514, 132539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Huang, J.; Zhuo, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, G.; Zheng, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Zeng, D. Improving wear and corrosion resistance of HVAF sprayed 316L stainless steel coating by adding TiB2 ceramic particles and CeO2. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 1313–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghwal, A.; Schulz, C.; Hall, C.; Vogli, E.; Berndt, C.C.; Ang, A.S.M. Microstructural, mechanical and high-temperature tribological performance of Fe-based fully amorphous and amorphous/crystalline coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 475, 130114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, A.; Han, J.; Meng, J. Effect of Si Addition on Tribological Properties of NbTaWMo Refractory High-Entropy Alloy at High Temperature. Tribol. Trans. 2021, 41, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-Y.; Pei, R.; Liu, S.; Wang, S.-L.; Dong, L.-J.; Zhou, L.-J.; Xi, Y.-C.; Bai, S.-L. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of different clad zones in multi-track Ni-based laser-clad coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 402, 126310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiarski, J.; Tylus, W.; Szczygiet, B. EIS and XPS investigations on the corrosion mechanism of ternary Zn–Co–Mo alloy coatings in NaCl solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 364, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.J.; Yang, Y.S. Corrosion properties and corrosion evolution of as-cast AZ91 alloy with rare earth yttrium. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 5043–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Luo, H.; Chen, X.; Prabhakar, J.M.; Wang, X.; Cheng, H.; Du, C.; Hu, S.; Li, X. The corrosion behavior and passive film properties of the cast and annealed AlCoCrFeNi2.1 eutectic high-entropy alloy in sulfuric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 2024, 240, 112456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkhchian, J.; Zarei-Hanzaki, A.; Schwarz, T.; Lawitzki, R.; Schmitz, G.; Schell, N.; Shen, J.; Oliveira, J.; Waryoba, D.; Abedi, H. Unleashing the microstructural evolutions during hot deformation of as-cast AlCoCrFeNi2.1 eutectic high entropy alloy. Intermetallics 2024, 168, 108253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | C | Si | P | S | Mn | V | Ti | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 1.50 | 0.10 | 0.05 | Balance |

| Element | Fe | C | Cr | V | Si |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | Balance | 2 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 1.2 |

| Sample | Ecorr/V | Icorr/A·cm−2 |

|---|---|---|

| substrate | −1.35 | 1.03 × 10−5 |

| 0.5 wt.% | −1.00 | 5.49 × 10−6 |

| 1 wt.% | −0.98 | 4.54 × 10−6 |

| 1.5 wt.% | −0.84 | 4.33 × 10−6 |

| 2 wt.% | −0.82 | 2.04 × 10−6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Huang, B.; Shi, H.; Xu, X.; Yu, S.; Long, H.; Ma, Z.; Pei, W. Effect of CeO2 on Microstructure and Properties of Cr3C2/Fe-Based Composite Coatings. Coatings 2026, 16, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020187

Liu Z, Huang B, Shi H, Xu X, Yu S, Long H, Ma Z, Pei W. Effect of CeO2 on Microstructure and Properties of Cr3C2/Fe-Based Composite Coatings. Coatings. 2026; 16(2):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020187

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zeyu, Baowang Huang, Haijiang Shi, Xin Xu, Shuo Yu, Haiyang Long, Zhanshan Ma, and Weichi Pei. 2026. "Effect of CeO2 on Microstructure and Properties of Cr3C2/Fe-Based Composite Coatings" Coatings 16, no. 2: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020187

APA StyleLiu, Z., Huang, B., Shi, H., Xu, X., Yu, S., Long, H., Ma, Z., & Pei, W. (2026). Effect of CeO2 on Microstructure and Properties of Cr3C2/Fe-Based Composite Coatings. Coatings, 16(2), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020187