Unveiling the Diverse Effects of Water Cuts in a Supercritical CO2 Environment on the Corrosion Behavior of P110 Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

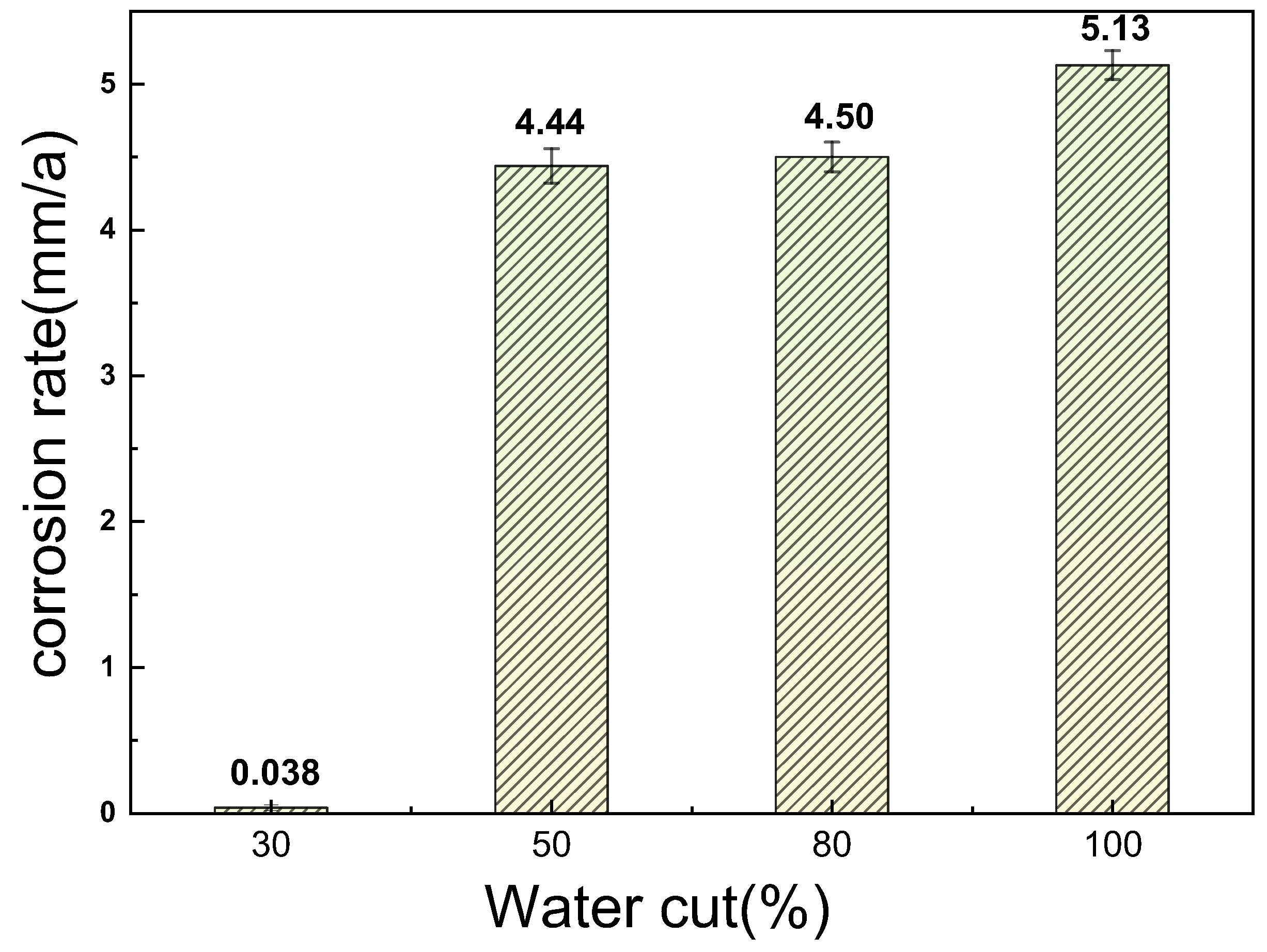

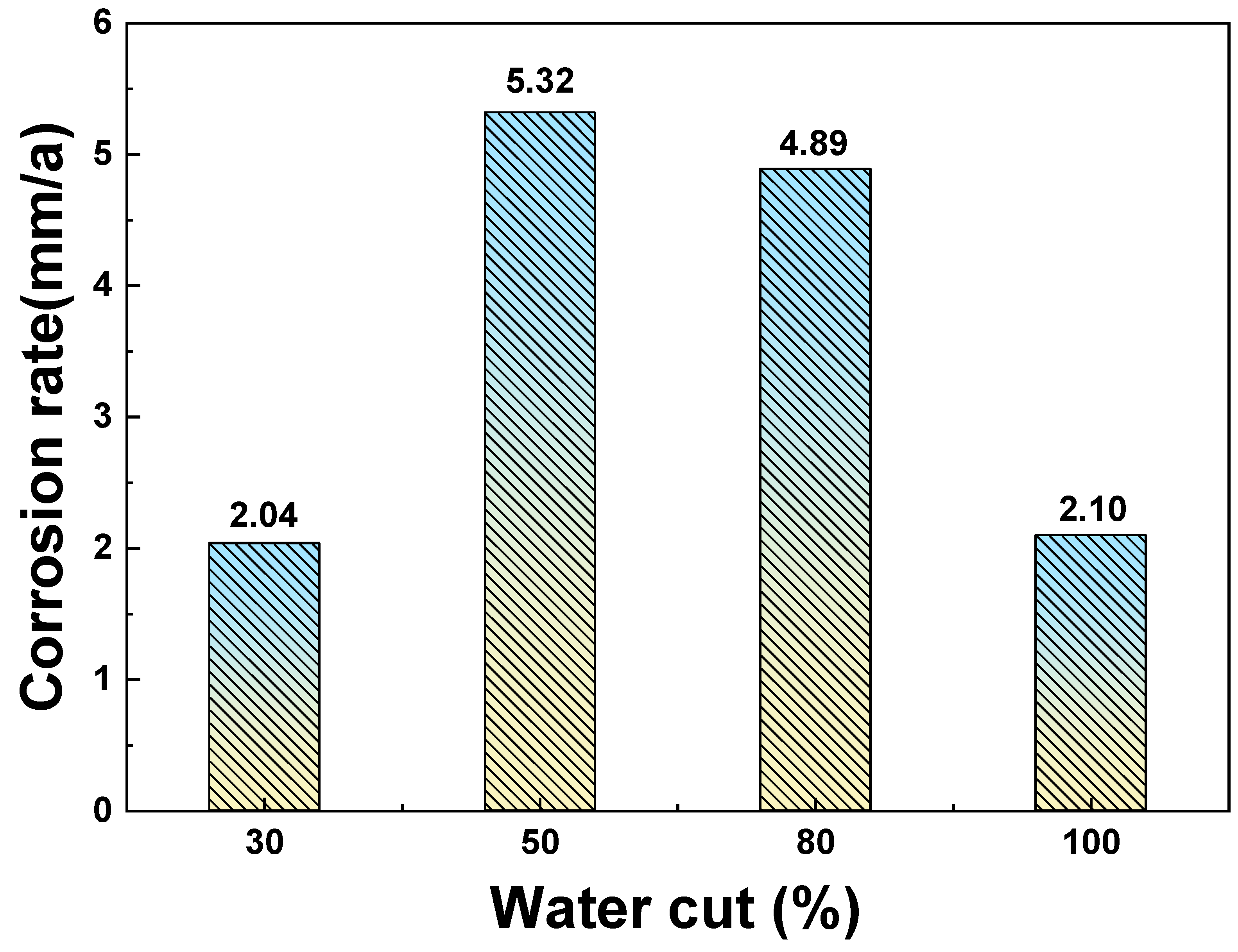

3.1. Corrosion Rate and Corrosion Morphology

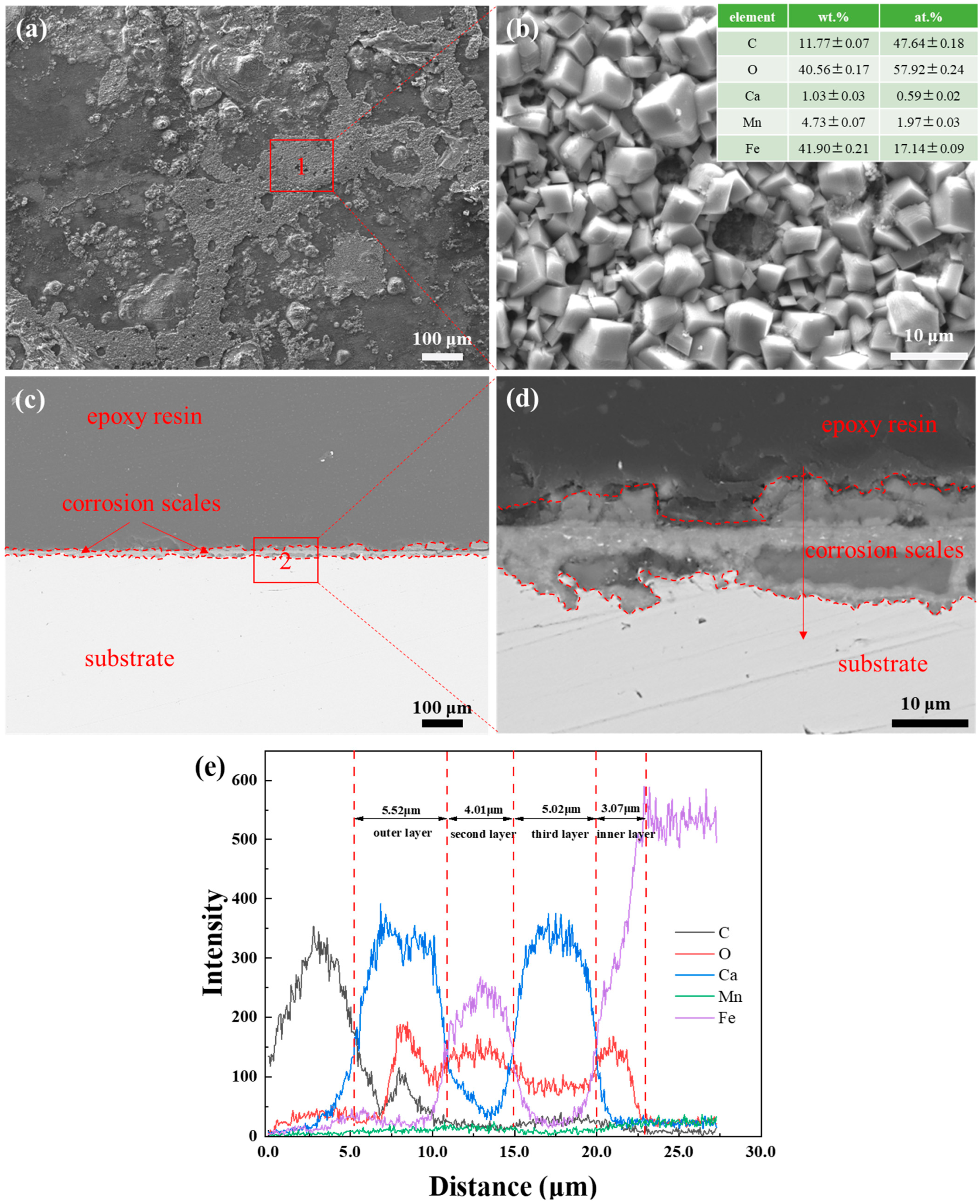

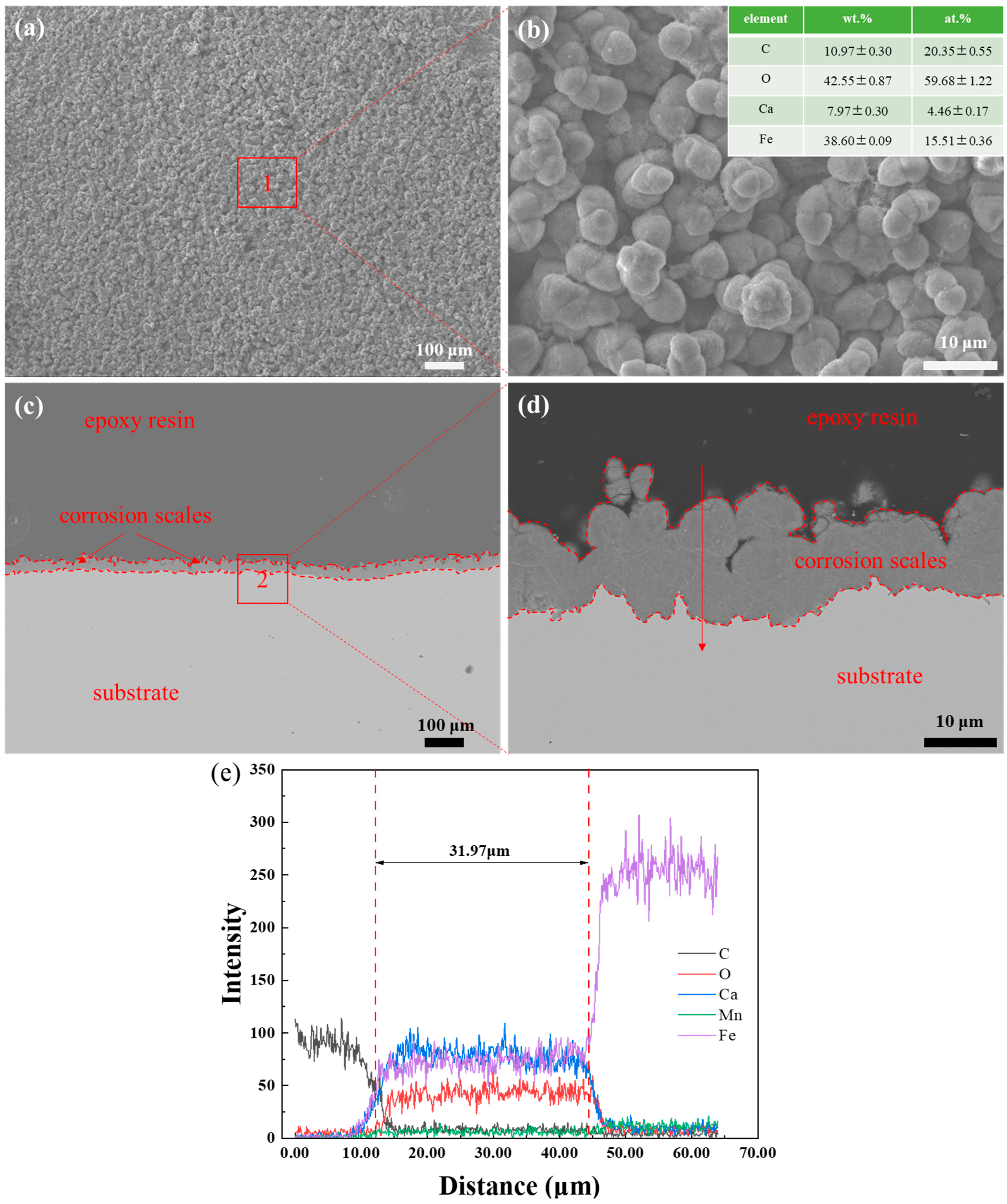

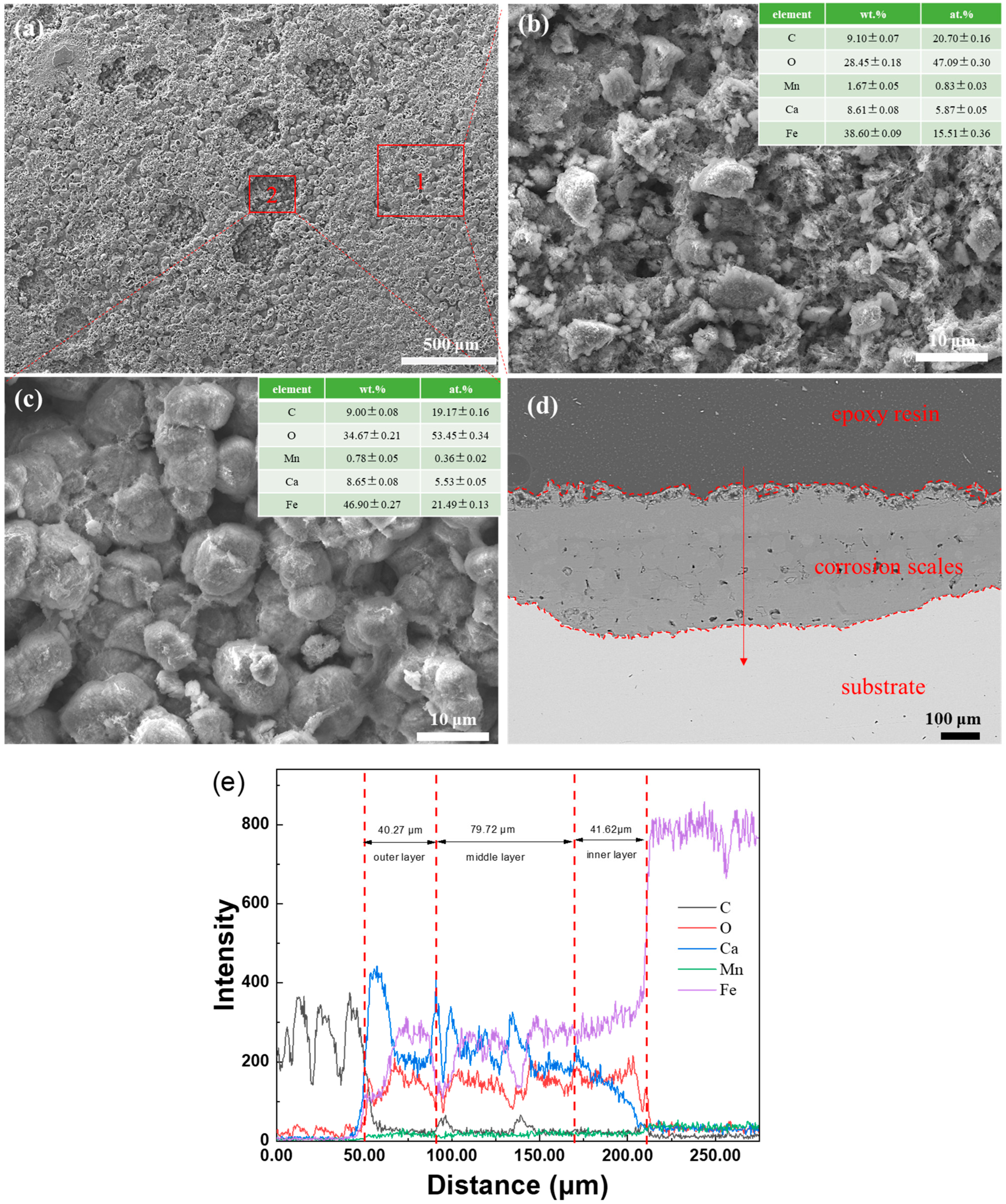

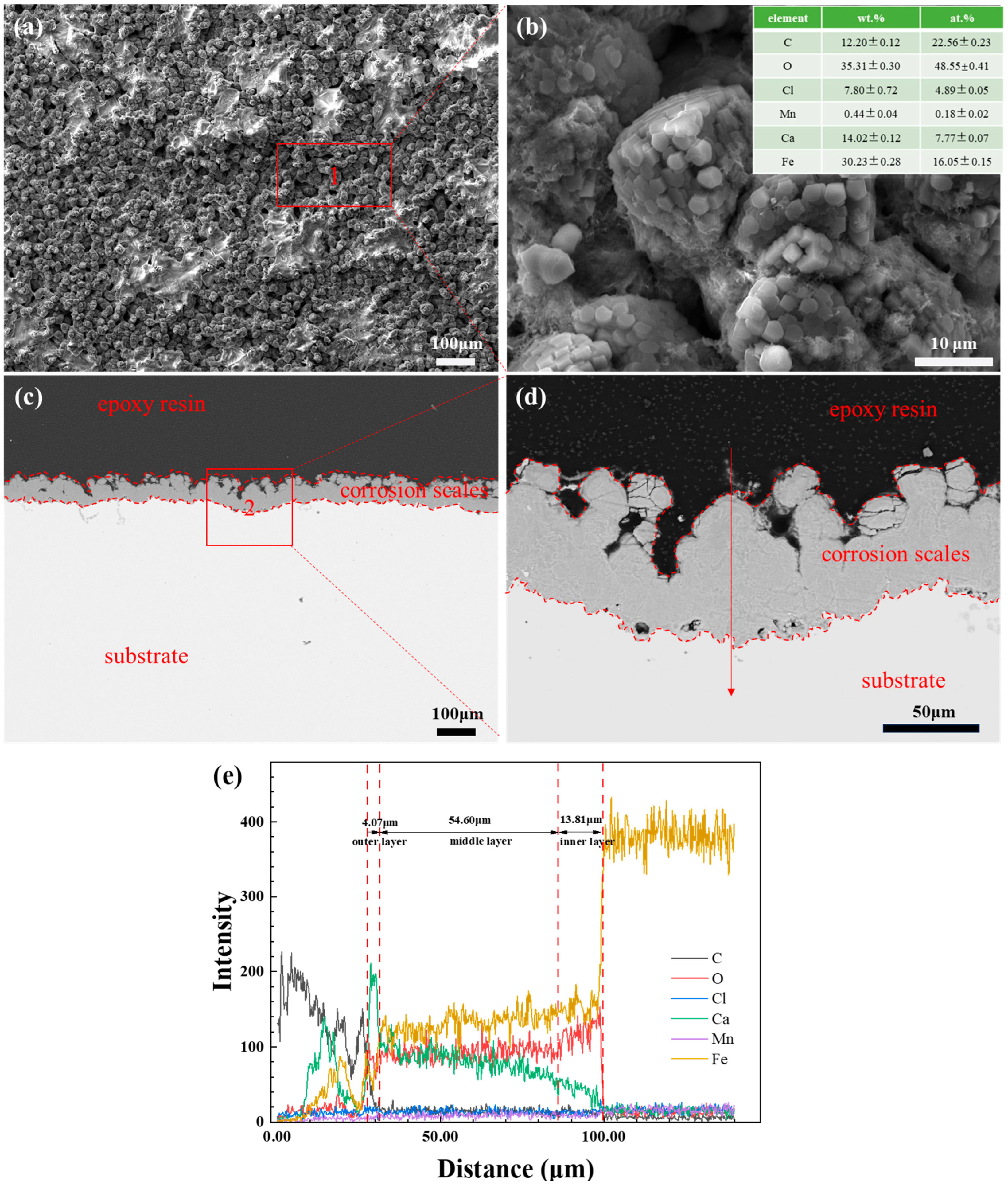

3.2. SEM Observation and EDS Analysis of Corrosion Scales

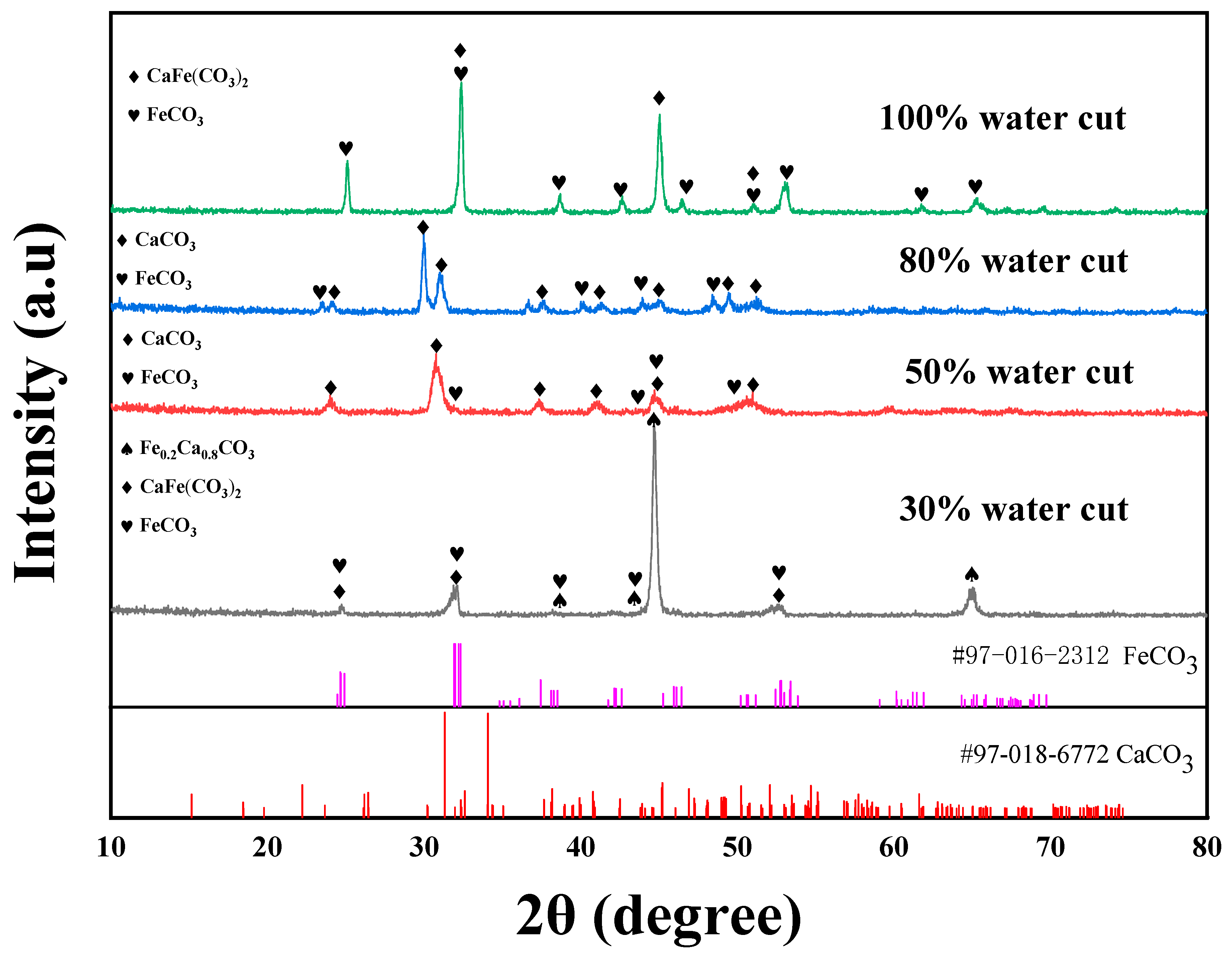

3.3. XRD Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of Water Cut on Uniform and Localized Corrosion

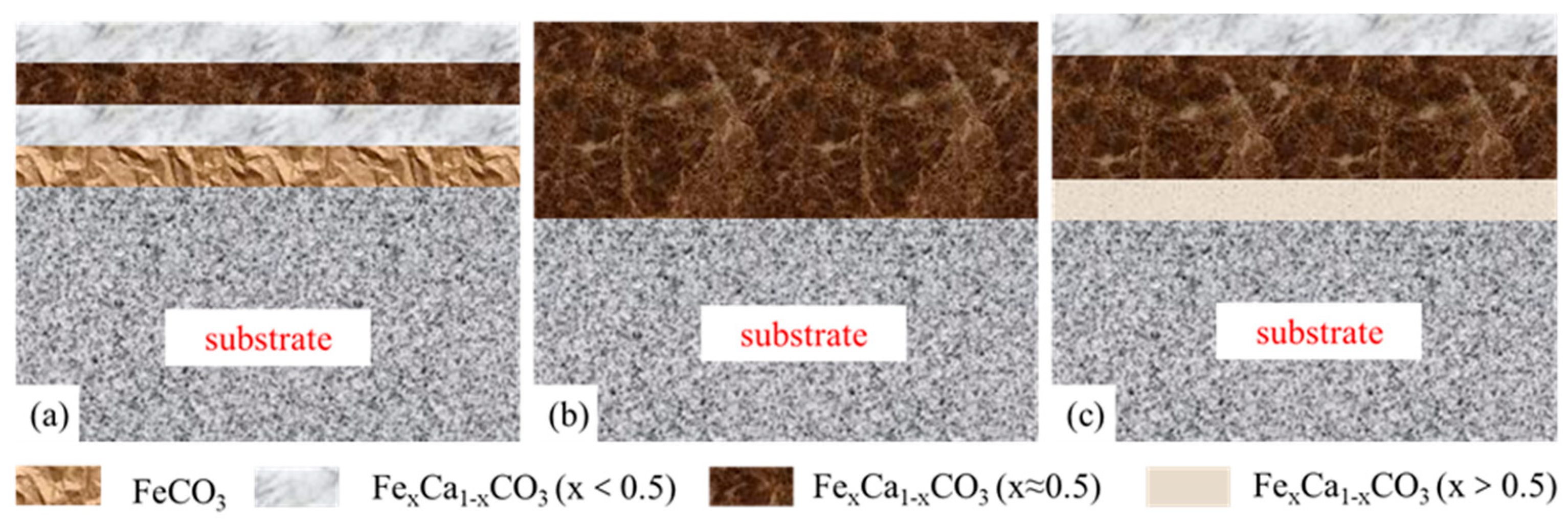

4.2. The Effect of Water Cuts and Ca2+ Concentration on Corrosion Scale Formation

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- As the water cut increases from 30% to 100%, the corresponding uniform corrosion gradually rises. Notably, the uniform corrosion rate surged by approximately two orders of magnitude as the water cut increased from 30% to 50%, followed by a moderate increase up to a 100% water cut. In contrast, the localized corrosion rate displayed a distinct convex trend, culminating in a peak value at a 50% water cut. This critical transition at 50% is attributed to the hydrodynamic breakdown of the protective oil film and the formation of galvanic cells induced by inhomogeneous wetting.

- (2)

- The corrosion scales on the surface of P110 underwent significant morphological transitions driven by the thermodynamics of competitive ionic substitution between Ca2+ and Fe2+. The scale evolved from a heterogeneous multi-layered film at a 30% water cut to the uniform, kinetic-controlled single layer at 50% and, finally, to a diffusion-controlled tri-layer gradient structure at 100%. These structural transformations are fundamentally governed by the formation of calcium-substituted scales FexCa1−xCO3 with varying stoichiometry, dictated by the local balance between anodic iron dissolution and bulk calcium diffusion.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Leite, F.F.G.D.; Adeyemi, M.A.; Sarker, A.J.; Cambareri, G.S.; Faverin, C.; Tieri, M.P.; Castillo-Zacarías, C.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; et al. A paradigm shift to CO2 sequestration to manage global warming—With the emphasis on developing countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Liao, K.; He, G.; Zou, Q.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, S. Corrosion mechanism of X65 steel exposed to H2S/CO2 brine and H2S/CO2 vapor corrosion environments. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 106, 104774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shang, Q.; Zhou, L.; Jiao, Z. Utilizing macroscopic areal permeability heterogeneity to enhance the effect of CO2 flooding in tight sandstone reservoirs in the Ordos Basin. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.; Monea, M. IEA GHG Weyburn CO2 Monitoring & Storage Project Summary Report 2000–2004; Petroleum Technology Research Centre: Regina, SK, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.F.; Ma, X.; Huang, K.; Fu, L.D.; Azimi, M. Carbon dioxide transport via pipelines: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 121994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.; Al-Shargabi, M.; Wood, D.A.; Mehrad, M.; Rukavishnikov, V.S. Carbon dioxide sequestration through enhanced oil recovery: A review of storage mechanisms and technological applications. Fuel 2024, 366, 131313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.F.; Wang, H.X.; Zeng, Y.M.; Liu, J. Corrosion challenges in supercritical CO2 transportation, storage, and utilization—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 179, 113292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Ding, T.C.; Yang, S.; Li, J.W.; Zhao, X.F.; Lin, X.Q.; Sun, C.; Sun, J.B. Comparison of corrosion behavior of X52 steel in liquid and supercritical CO2 transport environments with multiple impurities. Corros. Commun. 2025, 18, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugstad, A. Mechanism of protective film formation during CO2 corrosion of carbon steel. In NACE CORROSION 1998; NACE International: Houston, TX, USA, 1998; p. 98031. [Google Scholar]

- Nesic, S.; Lee, K.L.J. A mechanistic model for carbon dioxide corrosion of mild steel in the presence of protective iron carbonate films—Part III: Film growth model. Corrosion 2003, 6, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R.; Burkle, D.; Charpentier, T.; Thompson, H.; Neville, A. A review of iron carbonate (FeCO3) formation in the oil and gas industry. Corros. Sci. 2018, 142, 312–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesic, S. Key issues related to modelling of internal corrosion of oil and gas pipelines—A review. Corros. Sci. 2007, 49, 4308–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Pang, X.L.; Liu, C.; Gao, K.W. Formation mechanism and protective property of corrosion product scale on X70 steel under supercritical CO2 environment. Corros. Sci. 2015, 100, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pang, X.; Qu, S.; Li, X.; Gao, K. Discussion of the CO2 corrosion mechanism between low partial pressure and supercritical condition. Corros. Sci. 2012, 59, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, B.D. Predicting the conductivity of water-in-oil solutions as a means to estimate corrosiveness. Corrosion 1998, 54, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Cepulis, R.L.; Lee, J.B. Carbon dioxide corrosion of L-80 grade tubular in flowing oil-brine two-phase environments. Corrosion 1989, 45, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, K.E.; Richter, S.; Babic, M.; Nešić, S. Experimental study of oil-water flow patterns in a large diameter flow loop—The effect on water wetting and corrosion. Corrosion 2016, 72, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Tang, X.P.; Ayello, F.; Cai, J.Y.; Nesic, S.; Cruz, C.I.T.; Al-Khamis, J.N. Experimental study on water wetting and CO2 corrosion in oil-water two-phase flow. In NACE CORROSION 2006; NACE International: Houston, TX, USA, 2006; p. 06595. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.Z.; Zi, M.; An, Q.L.; Han, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Song, G.L. Fluid structure governing the corrosion behavior of mild steel in Oil-water mixtures. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ouyang, J.; Wang, Z.M. Exploring the dynamic mechanism of water wetting induced corrosion on differently pre-wetted surfaces in oil–water flows. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 664, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, H.; Guo, H.; Cai, L.; Li, X.; Hua, Y. A synergistic experimental and computational study on CO2 corrosion of X65 carbon steel under dispersed droplets within oil/water mixtures. Corros. Commun. 2023, 12, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y. Effect of water cut on the localized corrosion behavior of P110 tube steel in supercritical CO2/oil/water environment. Corrosion 2016, 72, 1470–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, B.; Ko, M.; Laycock, N.; Burnell, J.; Kappen, P.; Kimpton, J.A.; Williams, D.E. In situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction study of scale formation during CO2 corrosion of carbon steel in sodium and magnesium chloride solutions. Corros. Sci. 2012, 56, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, R.; Ambat, R. Effect of initial CaCO3 saturation levels on the CO2 corrosion of 1Cr carbon steel. Mater. Corros. 2021, 72, 1076–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zeng, D.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Yu, C.; Yi, Y.; Dong, B. The effects of Cl− and Ca2+ on corrosion and scale formation of 3Cr steel in CO2 flooding produced fluid. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 85, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeely, S.N.; Choi, Y.-S.; Young, D.; Nešić, S. Effect of Calcium on the Formation and Protectiveness of Iron Carbonate Layer in CO2 Corrosion. Corrosion 2013, 69, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Shamsa, A.; Barker, R.; Neville, A. Protectiveness, morphology and composition of corrosion products formed on carbon steel in the presence of Cl−, Ca2+ and Mg2+ in high pressure CO2 environments. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 455, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Lu, Y.; Wei, Q.; Yu, L.; Zhai, K.; Tang, J.; Wang, H.; Xie, J. The influence of Ca2+ on the growth mechanism of corrosion product film on N80 steel in CO2 corrosion environments. Corros. Sci. 2023, 218, 111168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, M.; Yang, G.; Han, B. Solubility of CO2 in aqueous solutions of NaCl, KCl, CaCl2 and their mixed salts at different temperatures and pressures. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2011, 56, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, D.; Liu, C.; Yang, Z.; Fan, H.; Wei, Z.; Wu, H.; He, C. Corrosion behavior of N80 steel in CO2-saturated brine coupled with ultra-high Cl− and Ca2+ concentrations under static and flowing states. Gas Sci. Eng. 2025, 135, 205547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.X. Physical Chemistry of Surfactant; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 1991; p. 387. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, M.; Gulbrandsen, E.; Sjöblom, J. CO2 corrosion inhibition and oil wetting of carbon steel with ferric corrosion products. In NACE CORROSION 2009; NACE International: Houston, TX, USA, 2009; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoori, H.; Young, D.; Brown, B.; Singer, M. Influence of calcium and magnesium ions on CO2 corrosion of carbon steel in oil and gas production systems—A review. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 59, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xu, L.N.; Liu, G.Z.; Lu, M.X. Corrosion behavior and mechanism of 3Cr steel in CO2 environment with various Ca2+ concentration. Corros. Sci. 2018, 136, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Gao, K.W.; Chen, C.F. Effect of Ca2+ on CO2 corrosion properties of X65 pipeline steel. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2009, 16, 661–666. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.P.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, W.L.; Xie, J.F.; Wang, J.D.; Liu, B.; Zeng, G.X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F.H. Effect of extremely aggressive environment on the nature of corrosion scales of HP-13Cr stainless steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 469, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.A.; Cheng, Y.F. On the fundamentals of electrochemical corrosion of X65 steel in CO2-containing formation water in the presence of acetic acid in petroleum production. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordsveen, M.; Nešić, S.; Nyborg, R.; Stangeland, A. A mechanistic model for carbon dioxide corrosion of mild steel in the presence of protective iron carbonates films—Part 1: Theory and verification. Corrosion 2003, 59, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.Q.; Xu, L.N.; Zhang, L.; Chang, W.; Lu, M.X. Corrosion of alloy steels containing 2% chromium in CO2 environments. Corros. Sci. 2012, 63, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Barker, R.; Neville, A. Comparison of corrosion behaviour for X-65 carbon steel in supercritical CO2-saturated water and water-saturated/unsaturated supercritical CO2. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 97, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.B.; Liu, W.; Chang, W.; Zhang, Z.H.; Li, Z.T.; Yu, T.; Lu, M.X. Characteristics and formation mechanism of corrosion scales on low-chromium X65 steels in CO2 environment. Acta Metall. Sin. 2009, 45, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

| Element | C | Mn | Cr | Si | Ni | Cu | V | P | S | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (wt.%) | 0.26 | 1.30 | 0.090 | 0.23 | 0.071 | 0.026 | 0.004 | 0.0068 | 0.0045 | Balance |

| Composition | HCO3 | Cl | SO42− | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | K+ | Na+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (mg L−1) | 189 | 128,000 | 430 | 8310 | 561 | 6620 | 76,500 |

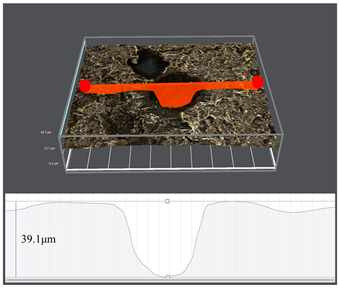

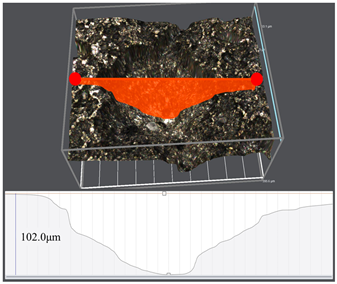

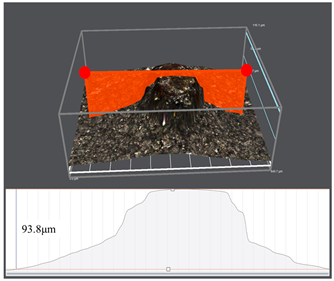

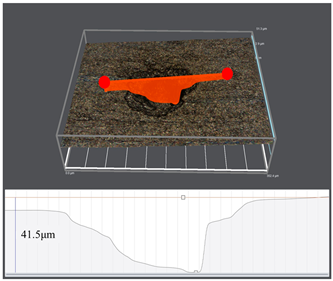

| Water Cuts | Macroscopic Surface Morphologies | Maximum Pitting Depth |

|---|---|---|

| 30% |  |  |

| 50% |  |  |

| 80% |  |  |

| 100% |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xie, J.; Zhao, M.; Song, W.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Fu, A.; Lei, T.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, J.; et al. Unveiling the Diverse Effects of Water Cuts in a Supercritical CO2 Environment on the Corrosion Behavior of P110 Steel. Coatings 2026, 16, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020184

Xie J, Zhao M, Song W, Li X, Chen H, Fu A, Lei T, Zhang J, Yang Z, Yuan J, et al. Unveiling the Diverse Effects of Water Cuts in a Supercritical CO2 Environment on the Corrosion Behavior of P110 Steel. Coatings. 2026; 16(2):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020184

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Junfeng, Mifeng Zhao, Wenwen Song, Xuanpeng Li, Hongwei Chen, Anqing Fu, Tengjiao Lei, Juantao Zhang, Zhongwu Yang, Juntao Yuan, and et al. 2026. "Unveiling the Diverse Effects of Water Cuts in a Supercritical CO2 Environment on the Corrosion Behavior of P110 Steel" Coatings 16, no. 2: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020184

APA StyleXie, J., Zhao, M., Song, W., Li, X., Chen, H., Fu, A., Lei, T., Zhang, J., Yang, Z., Yuan, J., & Li, Y. (2026). Unveiling the Diverse Effects of Water Cuts in a Supercritical CO2 Environment on the Corrosion Behavior of P110 Steel. Coatings, 16(2), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020184