1. Introduction

The demand for efficient and sustainable use of precious metals has become increasingly important in the development of modern technologies. Platinum, despite its high cost, continues to be indispensable due to its exceptional properties that include high catalytic activity, chemical stability, and superior resistance to corrosion [

1,

2]. Instead of employing bulk platinum, which significantly increases production costs, the application of thin film coatings offers an effective way of retaining the material’s desirable characteristics while drastically reducing its overall consumption [

3]. Magnetron sputtering has emerged as a particularly suitable technique for producing such coatings. Unlike many conventional deposition methods, this process ensures precise control of film thickness and microstructure, while also minimizing material waste. The technique is not only reproducible and scalable, but also adaptable to specific industrial needs, enabling the preparation of coatings with tailored mechanical [

4], chemical [

5], electrical [

6] or electrochemical properties [

7,

8]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that changes in deposition conditions, such as discharge power, process pressure, or sputtering time, can directly affect surface morphology, adhesion strength, catalytic behavior, and protective performance of thin metal and metal oxide films [

3,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Sakaliūnienė et al. [

3] determined that an appropriate selection of deposition parameters, particularly the argon pressure within the chamber, can reduce the residual stress in platinum films to values in the megapascal range. Chang et al. [

2] investigated the dependence of the electrochemically active surface area on the thickness and porosity of platinum thin-film anodes. The results revealed two distinct deposition regimes: dense films obtained at lower pressures (0.67–5.33 Pa) and porous films formed at higher pressures (8–16 Pa). Slavcheva et al. [

10] demonstrated that the morphology and electrochemical performance of sputtered (via DCMS) Pt films can be effectively tailored by adjusting process parameters. The power applied to the sputtering target is a critical deposition parameter that strongly influences the structural and functional properties of the resulting coating. Ozdemir et al. [

14] demonstrated that sputtering power plays a crucial role in determining the morphology and catalytic performance of Pt thin films. An optimal power level yielded highly active, homogeneous films with maximized electrochemical surface area, while higher powers led to particle coarsening and reduced catalytic efficiency. The pronounced sensitivity of the system highlights the critical role of systematic optimization in enhancing coating quality and overall performance. Conventional experimental approaches are often limited by substantial time and resource requirements. In this context, predictive simulation models represent a powerful complementary tool, enabling process optimization and reducing experimental workload. Numerous studies have employed various mathematical frameworks to model and optimize the magnetron sputtering process [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Ashok et al. [

19] have successfully optimized the sputtering process parameters using Taguchi analysis and response surface methodology to achieve minimal surface roughness and minimal sheet resistance.

Based on these considerations, the present work investigates the deposition of platinum thin films onto stainless steel 316L substrates using DC magnetron sputtering. The study systematically varies deposition parameters—namely discharge current, chamber pressure, and sputtering duration—to evaluate their influence on deposition rate and final coating thickness. The overarching objective of this work is to develop a data-driven framework capable of reliably predicting and optimizing deposition outcomes, thereby improving both the efficiency and reproducibility of magnetron sputtering processes.

By addressing these relationships, this research aims to contribute to the rational design and optimization of platinum-based thin-film systems, combining the advantages of reduced material usage with high-performance surface functionality. Such an approach is particularly relevant for industrial environments where rapid parameter selection, reduced experimental burden, and consistent coating quality are essential for process scalability and economic viability. Building upon our previous conference contribution [

12], which presented a preliminary proof-of-concept using a single modeling approach and a limited dataset, this study extends that work by conducting a systematic comparison of multiple machine-learning models, incorporating Gaussian Process Regression with uncertainty quantification, and implementing an active-learning strategy to improve data efficiency. Furthermore, the application of these advanced modeling and optimization approaches enables the prediction of optimal deposition conditions, reduces the need for extensive experimental trials, and improves reproducibility and efficiency in film fabrication, thereby providing a more rigorous and comprehensive framework than the earlier study.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, cylindrical substrates were prepared from an AISI 316L stainless steel rod with a diameter of 6 mm, which was cut into eight equal specimens to serve as deposition substrates. The surfaces were mechanically polished up to a 1200-grit finish to provide consistent topography and minimize variability in film adhesion and growth. Surface roughness was evaluated using an optical profilometer (Profilm3D, KLA Instruments, Milpitas, CA, USA), yielding an average Sa value of 0.1043 μm. Prior to deposition, the polished specimens were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath for 4 min, then cleaned with ethanol and dried with compressed air to remove residual debris and contaminants.

Thin film deposition was conducted in a Q150T ES Plus (Quorum Technologies Limited Company, London, England)DCMS system (

Figure 1) equipped with a platinum target of 50.8 mm diameter and 99.99% purity. The target-to-substrate distance was 45 mm, while the substrate holder was continuously rotated at a constant speed to achieve uniform deposition. No intentional substrate heating or substrate bias was applied during any of the depositions; substrates remained at near-ambient temperature throughout the process. The chamber was evacuated to a base pressure of 5 × 10

−4 mbar, after which high-purity argon (99.99%) was introduced as the working gas. Before initiating the deposition process, the chamber atmosphere was stabilized by purging with argon for 2 min. In addition, the platinum target was subjected to a pre-sputtering step at 150 mA for 2 min, a procedure routinely employed to remove surface oxides and impurities from the target surface, thereby providing stable plasma conditions and improving the purity of the deposited coating.

Gas flow rates were adjusted to reach the desired operating pressures, while discharge current was varied between 50 and 70 mA and deposition time between 2 and 12 min, according to the experimental design shown in

Table 1.

Film growth was monitored in situ by means of a quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) integrated into the sputtering system. This method enabled continuous measurement of mass accumulation on the substrate, which was automatically converted into deposition rate (nm min−1) and coating thickness (nm) using calibration constants of the system. In this way, the influence of discharge current, pressure, and deposition time on film formation could be directly evaluated during each experiment. The calibration employed a bulk platinum density of 21.45 g/cm3 and a tooling factor of 2.30.

Coated stainless steel samples processed by various combinations of process parameters values are presented in

Figure 2.

The measured outputs were subsequently organized into a dataset where each experimental condition (defined by discharge current, chamber pressure, and deposition time) corresponded to a pair of response values (deposition rate and coating thickness). In this way, the directly measured deposition characteristics were transformed into structured inputs for model training and validation, enabling systematic exploration of parameter–response relationships and optimization of sputtering conditions.

3. Results

This study focuses exclusively on process metrics obtained from QCM measurements, specifically coating thickness and deposition rate. Additional coating characteristics such as morphology, adhesion, and microstructure were not evaluated, as their assessment lies outside the scope of the present work. This subsection introduces the overall modeling and optimization framework applied to interpret the experimental data and guide process improvement.

3.1. Integrated Data Driven Modeling Framework

The experimental data were analyzed using an integrated approach combining classical regression, machine learning, and optimization techniques. The objective was to establish reliable predictive models for parameter–response relationships and to support both process optimization and experimental planning.

Linear regression was first applied to identify the dominant factors, providing a transparent baseline for subsequent analyses. To capture nonlinear dependencies and quantify prediction uncertainty, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) was then employed. GPR proved suitable for modeling within the limited parameter space and was validated using cross-validation procedures for both responses.

The developed GPR models served as the basis for multi-objective optimization aimed at finding balanced solutions between deposition rate and coating thickness. The resulting Pareto front illustrated the trade-offs between these competing objectives. Finally, an active learning strategy was implemented to identify new experimental points with the highest expected gain of information, linking predictive modeling with intelligent experimental design.

This integrated use of regression, machine learning, and optimization enhanced process understanding, improved predictive accuracy, and enabled resource-efficient planning of future experiments, an approach particularly suitable for systems where experimental trials are costly or time-intensive. Building upon the established modeling framework, the next step was to evaluate and compare candidate regression models.

3.2. Evaluation of Predictive Models

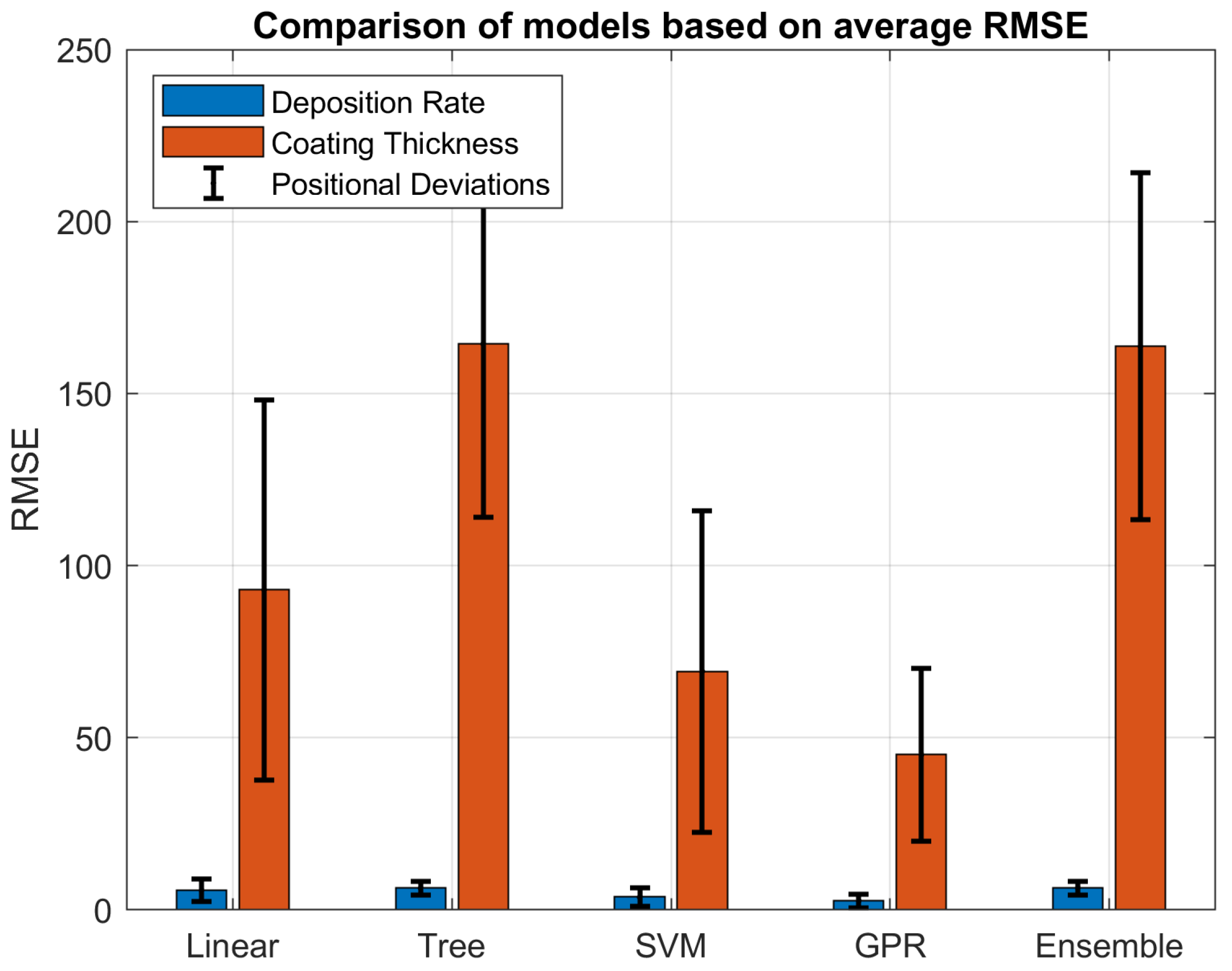

This subsection presents the comparison of several regression and machine learning models to identify the most accurate and stable predictive approach. To evaluate the reliability of candidate models, a five-fold cross-validation (K-fold CV) procedure was conducted across five different regression approaches: linear regression, regression trees, support vector machines (SVMs), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), and an ensemble method based on bagged trees. Five-fold cross-validation was chosen because, with only eight samples, it provides varied train–test splits and therefore a more reliable and informative estimate of model performance. As an example, one fold may have contained two test samples, whereas others included only one due to the small dataset. The assessment was performed separately for both output variables, namely deposition rate and coating thickness.

Model performance was quantified in terms of the root mean square error (RMSE) as a measure of average prediction error, together with the corresponding standard deviations as indicators of variability. The results are summarized in the form of a table (

Table 2) and a bar chart (

Figure 3), where RMSE values and their associated deviations are presented for each modeling approach.

For the deposition rate, all models demonstrate relatively low error (RMSE < 10 nm min−1), indicating that this output is comparatively straightforward to predict. Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) and the SVM exhibit the lowest errors and minimal variability. In contrast, for coating thickness, the differences between models are markedly more pronounced.

Errors are higher (RMSE up to 160 nm) and exhibit substantial variability, reflecting a complex and nonlinear relationship between the input parameters and the resulting thickness. The GPR model showed comparatively lower error and lower variance than the other tested models, suggesting that it may be suitable for predicting coating thickness and deposition rate within the examined dataset.

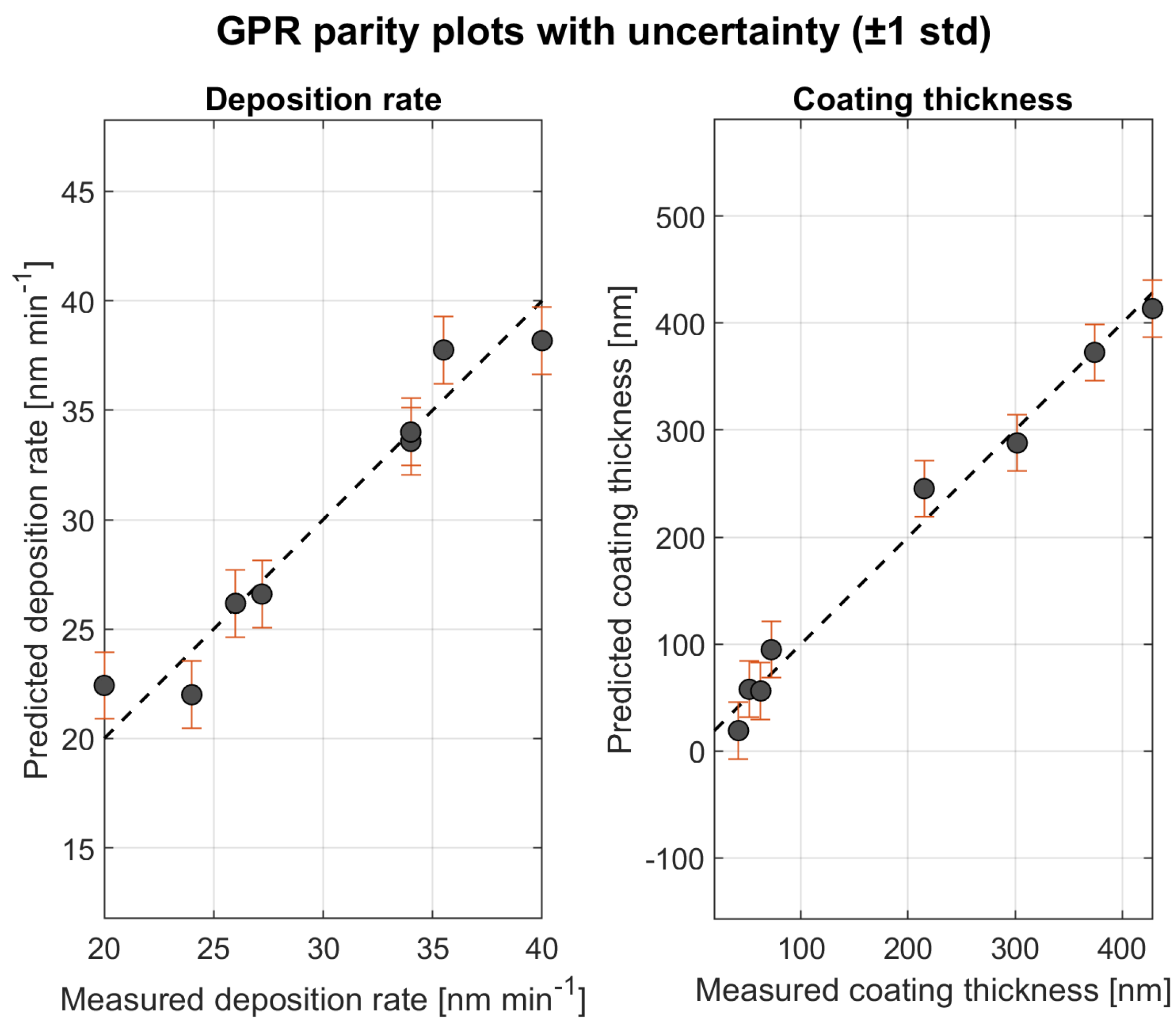

To complement the RMSE-based comparison presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 3, parity plots of the GPR models for deposition rate and coating thickness were generated and are shown in

Figure 4. The predicted values closely follow the measured data, demonstrating that the GPR model captures the main trends. The uncertainty bounds shown as ±1 standard deviation error bars provide a direct visual indication of the model’s confidence.

The uncertainty is constant across the dataset, which is typical for GPR models trained on very small and evenly spaced datasets, where the variance depends mainly on the distribution of input points.

These results indicate that GPR is a stable and accurate model for predicting both outputs, especially for the more challenging target of coating thickness. It was therefore chosen for the subsequent analyses, including Pareto optimization and active learning. The observed high errors in thickness prediction may be attributed to measurement variability, such as spatial non-uniformity in film growth, the strong nonlinear dependence between process parameters and thickness, and the potential need for additional input variables, including temperature or substrate surface roughness.

Based on the results of the model comparison, linear regression was further analyzed to quantify the effect of individual parameters.

3.3. Linear Analysis of Parameter Influence

This part focuses on assessing the relative influence of the input parameters using a linear regression model as a transparent baseline for interpretation.

For a clearer comparison of parameter influence, the linear model was trained on standardized input variables.

Table 3 and

Table 4 report the corresponding standardized regression coefficients (weights), while the bar plot in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 shows their absolute values, providing a scale-independent visualization of the relative importance of each parameter.

3.3.1. Coating Thickness

Building on the model evaluation, this subsection analyzes how deposition parameters affect the coating thickness within the linear approximation. The results of the linear regression model indicate that deposition time has by far the greatest influence on coating thickness among all input parameters (

Figure 5). The contributions of discharge current and pressure in this model are negligible, suggesting that within the considered range of values, they do not significantly affect coating thickness. This finding aligns with physical intuition, as longer process durations allow for the deposition of a greater amount of material, whereas at the same time, variations in current or pressure do not result in significant changes. However, due to its inherent nature, the linear model cannot detect potential nonlinear effects of current or pressure. Although such effects are not evident in this case, identifying them would require a more advanced model, such as GPR or nonlinear regression, or a larger experimental dataset, particularly covering an extended range of parameter values.

The linear analysis confirms that deposition time is the most critical factor in determining coating thickness (

Table 3), consistent with the physical understanding of the process. For a more detailed investigation of the smaller influences of other parameters, a more sophisticated modeling approach would be beneficial.

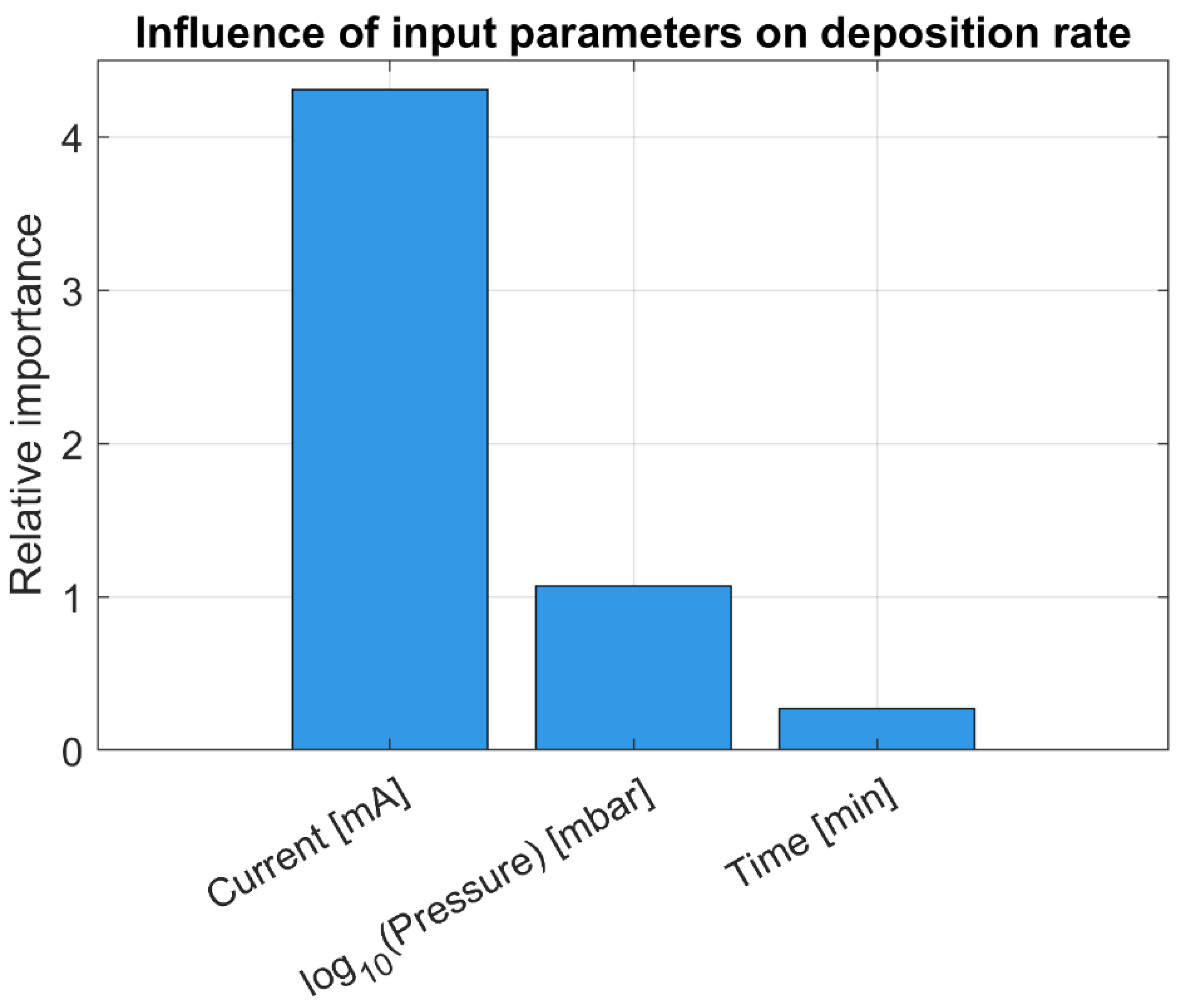

3.3.2. Deposition Rate

Similarly, the influence of process parameters on the deposition rate was assessed using the same linear model. The results of the linear regression analysis indicate that among all input parameters, discharge current has the greatest influence on the deposition rate (

Figure 6).

Discharge current directly determines the amount of energy available for material deposition, which is reflected in a higher deposition rate. Pressure (expressed as log10) has a moderate effect, but is significantly smaller than that of discharge current. It may influence the process through the dynamics of material transfer, yet within the observed range of values, its role is not critical. Deposition time has the least influence on the deposition rate, which is logical and implies that the duration of the process does not affect the instantaneous deposition rate but primarily determines the cumulative coating thickness. Over a unit of time (nm min−1), the deposition rate remains relatively constant regardless of how long the process continues.

This interpretation is also physically meaningful: discharge current, as the energy source, governs the intensity of deposition, pressure affects the overall transfer conditions, while time does not influence the rate itself but only dictates how long the rate is sustained, which is crucial for the total coating thickness.

Within this experimental range, the deposition rate exhibits a clear linear dependence primarily on discharge current, with pressure exerting a moderate effect and deposition time having minimal impact (

Table 4). These findings are consistent with the physical understanding of the process and support focusing optimization efforts primarily on adjusting the current.

3.4. Response Surface Modeling Using GPR

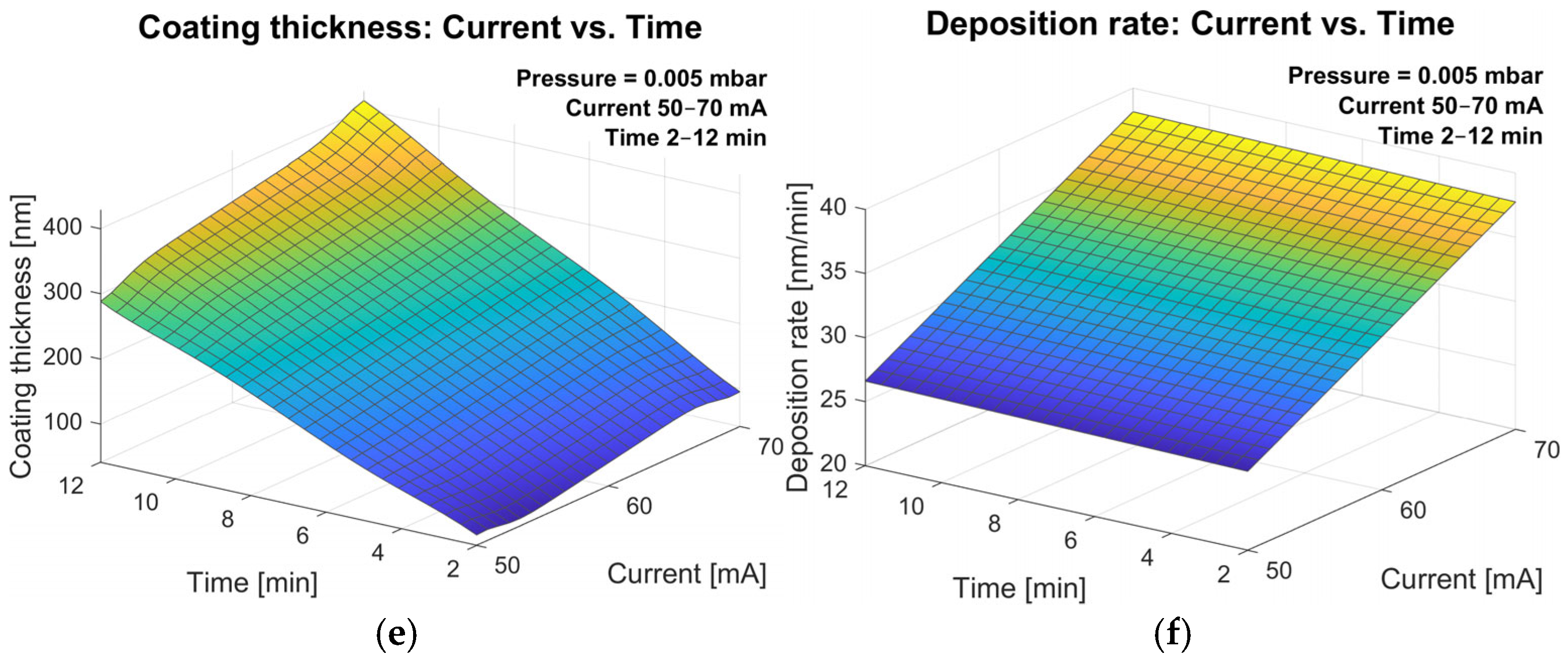

This section explores the nonlinear interactions between process parameters and responses through Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) and visualizes them as response surfaces. The GPR response surfaces reveal how discharge current, deposition time, and pressure jointly affect coating thickness and deposition rate. The response surfaces for coating thickness (

Figure 7a,c,e) display steeper gradients, particularly along the time axis, demonstrating that sputtering duration exerts the strongest effect on the amount of accumulated material. The thickness increases monotonically with both discharge current and deposition time, while the effect of pressure is comparatively weak within the examined range. The response surfaces show a slight decrease in deposition rate at higher pressures, consistent with the shorter mean free path of ions and increased collisional losses in the plasma, which reduce the effective sputtering yield. The surfaces are smooth and continuous, with limited curvature, confirming that the GPR model effectively captures the dominant process trends without overfitting.

For the deposition rate (

Figure 7b,d,f), a nearly planar and monotonic trend is observed, indicating a predominantly linear dependence on current and a minor effect of time or pressure. The deposition rate increases systematically with discharge current, confirming that the discharge current represents the dominant factor governing the sputtering yield and the overall energy available for sputtering yield. The influence of pressure is comparatively weak, with slightly higher discharge rates observed at lower pressure levels, reflecting the increased argon ion density that enhances sputtering efficiency.

The GPR models used to generate the response-surface plots exhibit high predictive accuracy. For the deposition rate, the model reached an

with an RMSE of 1.54 nm·min−1, while the coating-thickness model achieved an

and an RMSE of 17.4 nm. These results indicate that the response surfaces capture the main trends of the model behavior across the investigated parameter space.

Overall, the results highlight that coating thickness depends mainly on deposition time, with pressure contributing only secondary effects in the examined range of process parameters, whereas deposition rate is primarily governed by discharge current.

Building upon the response surface results, a quantitative sensitivity analysis was performed to determine local parameter effects.

Gradient-Based Sensitivity Analysis

This subsection provides a detailed quantitative assessment of how individual process parameters locally affect the coating thickness and deposition rate. The analysis was based on partial derivatives of the GPR response surfaces, which describe the rate of change in each response within the explored parameter space. Since these represent local variations, the values indicate how rapidly the response changes within the parameter space, but not necessarily across the entire range of parameter values. The apparently large gradients with respect to pressure arise from the narrow pressure interval; when expressed on the technical pressure scale, this effect would be about 1000 times smaller.

Absolute average partial derivatives of the modeled coating thickness with respect to discharge current, pressure, and deposition time were calculated across the entire parameter space:

- •

∂(thickness)/∂(current) = 2.01 nm mA−1,

- •

∂(thickness)/∂(log10(pressure)) = 171.39 nm min−1 log10(mbar)−1,

- •

∂(thickness)/∂(time) = 27.31 nm min−1.

These results indicate that deposition time has by far the strongest influence on coating thickness, while discharge current and pressure exert weaker secondary effects. Each additional minute of sputtering increases the film thickness by roughly 27 nm on average, confirming that process duration is the dominant factor controlling material accumulation. To avoid negative gradients caused by local slope variations in the sparse design space, parameter sensitivity was evaluated using the average absolute gradient of the GPR surface. This metric provides a robust and sign-independent measure of influence and is fully consistent with the monotonic increase in coating thickness with discharge current observed in the response surfaces (

Figure 7a,c,e). This behavior reflects the expected physical trend that higher discharge current enhances the sputtering yield.

Absolute average partial derivatives of the modeled deposition rate with respect to the input parameters were evaluated:

- •

∂(rate)/∂(current) = 0.209 nm min−1 mA−1,

- •

∂(rate)/∂(log10(pressure)) = 24.26 nm min−1 log10(mbar)−1,

- •

∂(rate)/∂(time) = 0.042 nm min−1 min−1.

The results confirm that discharge current is the dominant factor influencing the deposition rate, as indicated by the highest average absolute gradient among all input variables. The response surfaces (

Figure 7b,d,f) show a clear monotonic increase along the discharge current axis, consistent with the expected physical relationship whereby higher current enhances sputtering efficiency. In contrast, the influence of deposition time is minimal, reflecting the steady-state nature of the process, while the effect of pressure within the examined range remains comparatively modest. Consequently, optimization of deposition rate should primarily focus on the discharge current, with pressure and deposition time playing secondary roles.

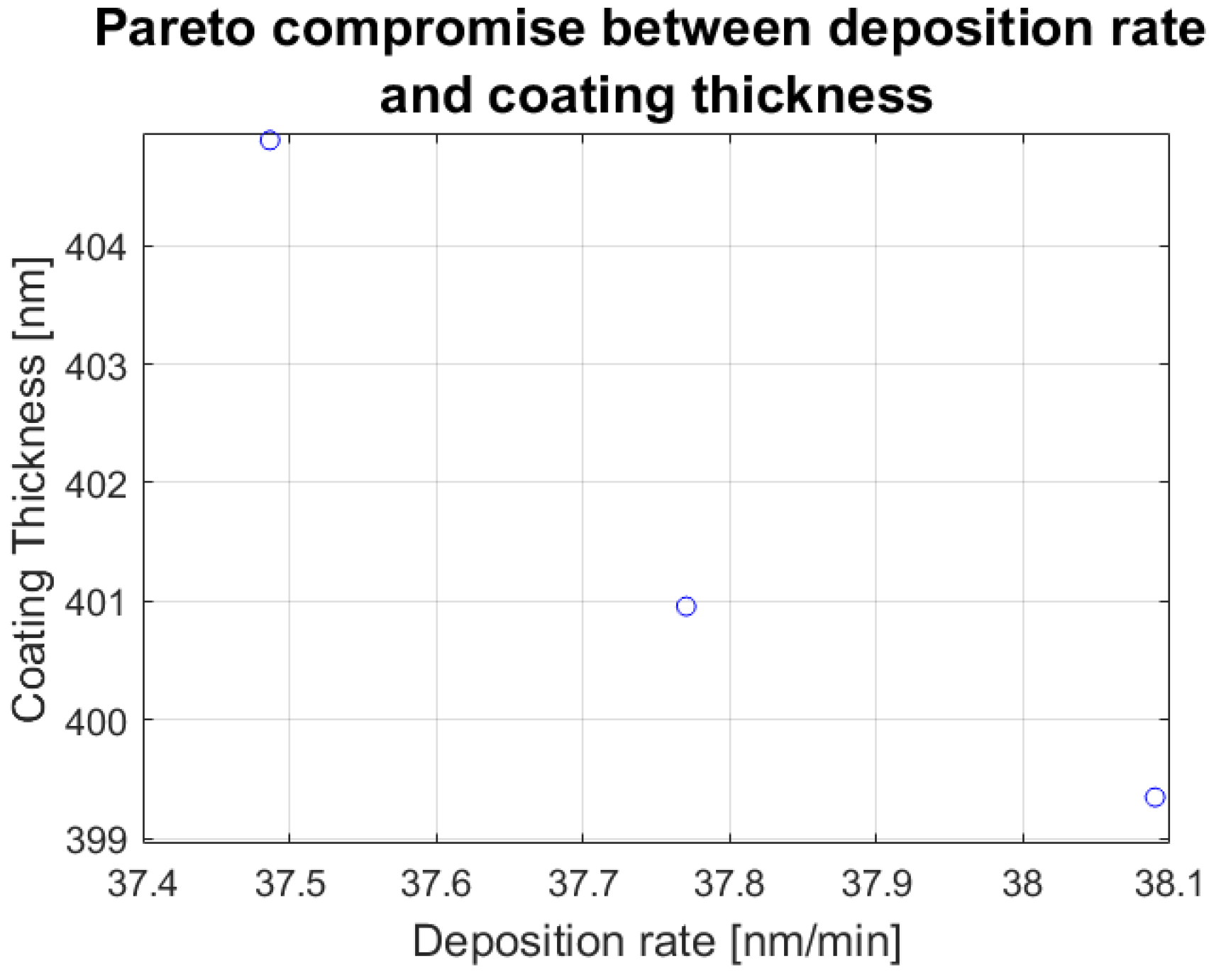

3.5. Multi-Objective Optimization and Pareto Front

Multi-objective optimization based on the GPR model was used to explore the relationship between coating thickness and deposition rate, with the resulting Pareto front providing a graphical representation of the trade-offs between the two objectives, enabling identification of parameter combinations that offer the best overall compromise. All points on the front represent optimal solutions predicted by the trained GPR model. Visualization of the results on the Pareto front enables the selection of an optimal point that best meets the specific requirements of the application, including achieving maximum thickness, highest deposition rate, or a compromise value between these parameters.

The results of the multi-objective optimization using the GPR model and MATLAB R2025a multi-objective Pareto search algorithm indicate that all points on the obtained Pareto front are highly concentrated around the same combination of input parameters: a discharge current of approximately 70 mA, a pressure of around 0.005 mbar, and a deposition time of about 12 min (

Figure 8). The values of the objective functions deposition rate and coating thickness differ only slightly among individual solutions, implying that, from both a numerical and engineering perspective, there is effectively a single optimal solution.

The Pareto front revealed a narrow optimal region, with deposition rates varying by less than 1 nm min−1 across all optimal solutions. This indicates that the process operates in a stable region of the parameter space, where small variations in discharge current, pressure, or deposition time led to only minor changes in the deposition rate. Coating thickness varies slightly (by approximately 5 nm) but follows the expected physical trade-off—thicker coatings are obtained at marginally lower deposition rates. Such a narrow Pareto front suggests that both objectives reach their near-optimal values simultaneously, implying that the process can be optimized without significant compromise between deposition rate and coating thickness.

Given the high concentration of solutions (

Table 5), this may suggest that the current model is strongly locally optimized. Expanding the parameter space or introducing additional input variables could allow exploration of a broader range of optimal solutions.

It is important to note that the Pareto-optimal conditions suggestion represents model-based predictions, as no additional verification experiments were conducted within the scope of this study.

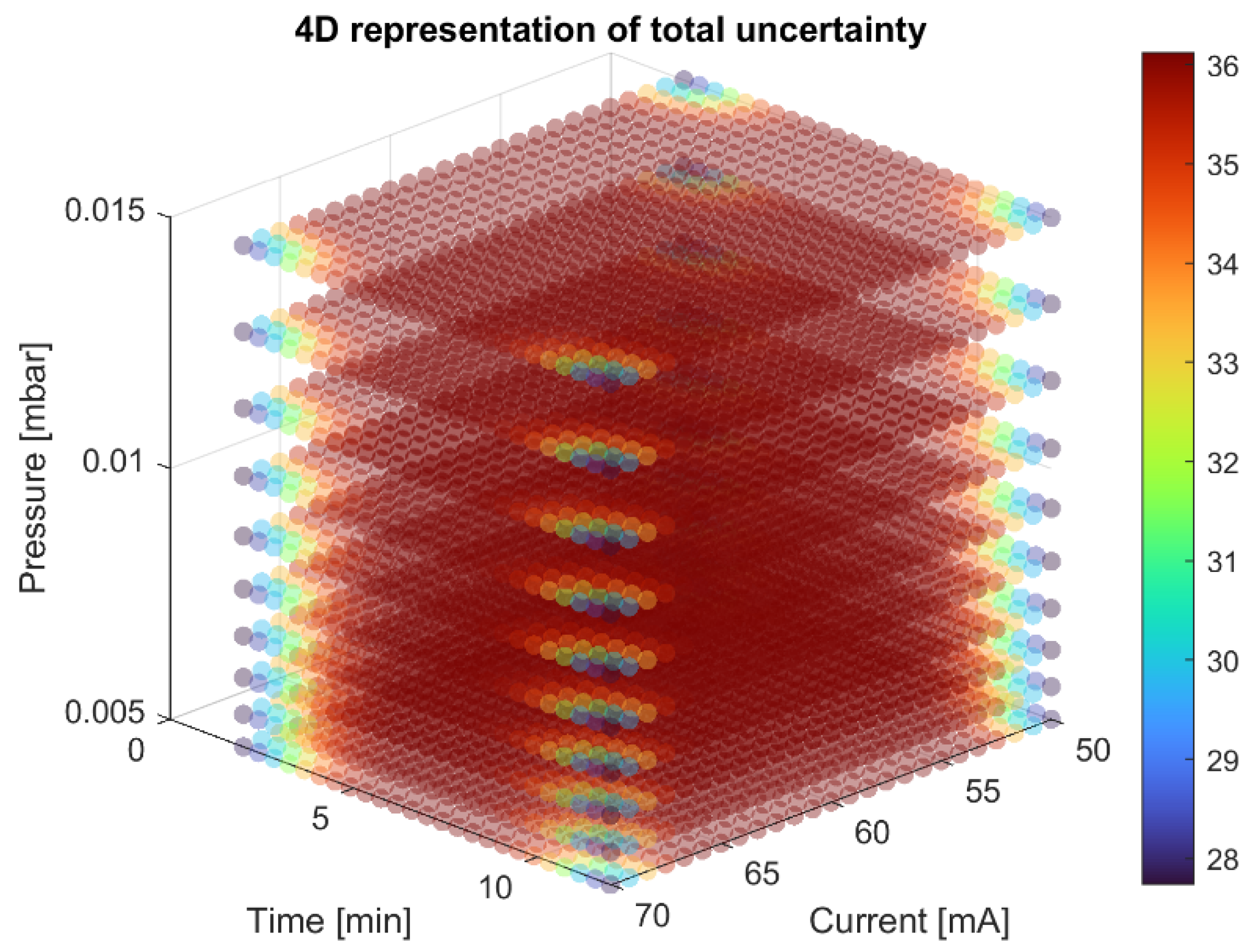

3.6. Uncertainty-Driven Active Learning

This subsection introduces an active learning strategy designed to identify the most informative new experimental point based on model-predicted uncertainty. Active learning is used to determine which new data points would be most valuable to obtain experimentally to improve predictive accuracy. This strategy is particularly useful in cases where measurements, experiments, or simulations are costly and time-consuming, as is the case for the magnetron sputtered platinum coating process. In this analysis, we employed active learning based on GPR models, applied separately for both output variables.

In addition to predicting output values, GPR models provide an estimate of the standard error of the prediction (uncertainty). This means that for each new combination of input parameters, we can assess how confident the model is in its prediction. Therefore, the greatest attention is given to regions where the model-predicted uncertainty is highest and new data is most needed. For active selection, we generated a dense 3D grid of possible parameter combinations:

- •

A total of 30 current values [50–70 mA],

- •

A total of 30 deposition time values [2–12 min],

- •

A total of 10 pressure levels (logarithmically spaced between 0.005 and 0.015 mbar).

For each of the 9000 data points, the standard error of prediction for the deposition rate (Std_Rate), the standard error of prediction for coating thickness (Std_Thickness), and their sum, representing the total uncertainty, were computed. Total uncertainty was calculated by summing the predicted standard deviations of the deposition rate and coating thickness GPR models, indicating regions where both predictions are least certain. Subsequently, the point exhibiting the highest total uncertainty was identified, corresponding to the most informative experiment, i.e., the location where an additional measurement would provide the greatest increase in model knowledge. Predictions and associated uncertainties were obtained, and the active learning point was selected by identifying the maximum of the total uncertainty. The resulting point chosen for further investigation is shown in

Table 6.

The model exhibits the lowest confidence at this point, likely due to increased nonlinearity or sparse data in this region of parameter space. The pressure is near its lower bound, which may result from higher response variability in this range. The deposition time and discharge current values are moderate, indicating that this experiment would enrich the model in a less-explored area.

For better insight, a 4D uncertainty visualization was prepared (

Figure 9), in which the X-axis represents the discharge current, the Y-axis represents the deposition time, and the Z-axis represents the pressure. The color of the points indicates the total model uncertainty. Active learning enables a systematic and targeted selection of new experimental points based on a formal assessment of model uncertainty. The proposed next measurement is directed toward the region with the highest informational value. This approach significantly enhances the efficiency of experimental design and provides a powerful tool for process optimization under limited resources.

Overall, the presented methodology demonstrates the capability of machine learning-assisted process optimization in thin film engineering, effectively linking experimental data with intelligent model-based decision making. The active-learning point should therefore be interpreted as a model-guided suggestion, as no additional deposition experiments were carried out to confirm this prediction.

4. Conclusions

A comprehensive analysis of the experimental data from magnetron-sputtered platinum coatings, supported by advanced machine-learning models and optimization methods, provided in-depth insight into the behavior of the thin-film deposition process. The results demonstrated that the input parameters exert different influences on individual responses: deposition time was identified as the primary factor affecting coating thickness, while discharge current had the greatest impact on deposition rate. Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) models were used to approximate nonlinear trends within the available dataset, enabling stable predictions and quantification of uncertainty. The constructed Pareto front revealed practically a single dominant solution, as both deposition rate and coating thickness reached their near-optimal values at the same parameter combination. The experimentally confirmed results concern only how discharge current, pressure, and deposition time influence deposition rate and coating thickness. In contrast, the optimal points suggested by the GPR model, the Pareto front, and the active-learning step should be interpreted solely as model-based insights.

The main limitation of the current model arises from the small number of experimental samples, which restricts the exploration of potential interactions beyond the investigated range. Thus, active learning further enhances experimental efficiency by proposing the point with the highest model-predicted uncertainty, where a new measurement would contribute most to improving the model’s predictive capability. This integrated framework represents a methodological contribution that combines data-efficient machine learning with multi-objective optimization and adaptive experiment selection.

The integration of Gaussian Process Regression, Pareto optimization, and active learning in sputtering process analysis represents a novel and comprehensive framework applicable to a broad range of thin-film materials. By combining classical experimental design with modern artificial intelligence and optimization methods, this approach enables better-informed decisions, reduces the number of required experiments, and accelerates the achievement of technological optimum.

From an industrial perspective, the presented methodology offers practical benefits by reducing the number of required sputtering trials, enabling faster parameter exploration, and supporting more reproducible process development. However, the real-world applicability of the results is constrained by the limited dataset and the absence of experimental validation of the model-suggested optimal conditions. Consequently, the optimization and active-learning outputs should be interpreted as guidance for future process refinement rather than fully validated operational settings.

Future work will extend the experimental domain in accordance with the active learning results and beyond, incorporating additional parameters such as substrate temperature and target–substrate distance to further enhance model accuracy and predictive generality.

Overall, the methodology demonstrated provides a reproducible framework for data-driven optimization of sputtered coatings, offering strong potential for adaptation to other materials and deposition processes.