A First-Principles Study of Lithium Adsorption and Diffusion on Graphene and Defective-Graphene as Anodes of Li-Ion Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computational Method

3. Results and Discussions

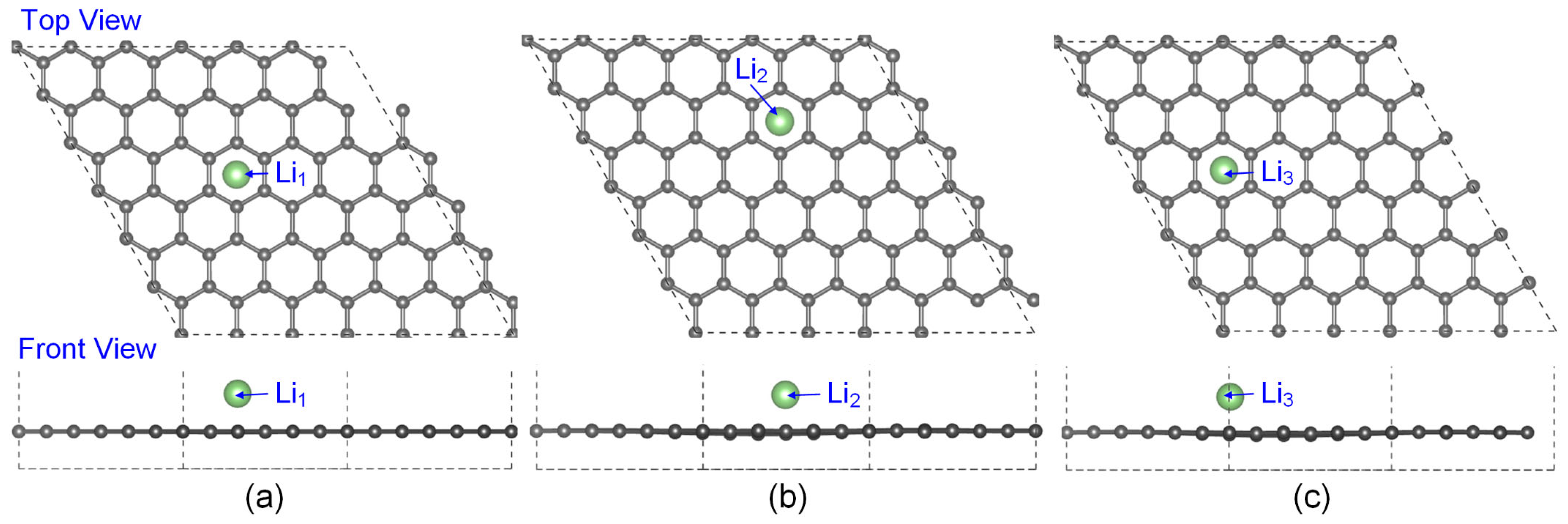

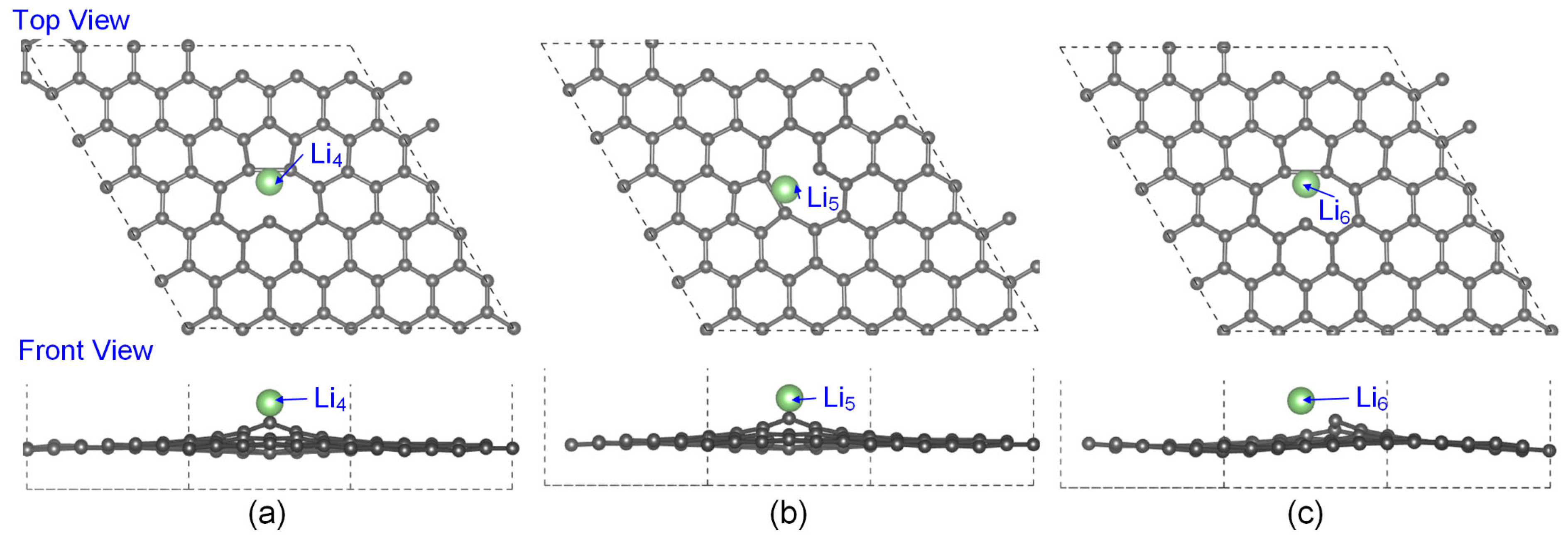

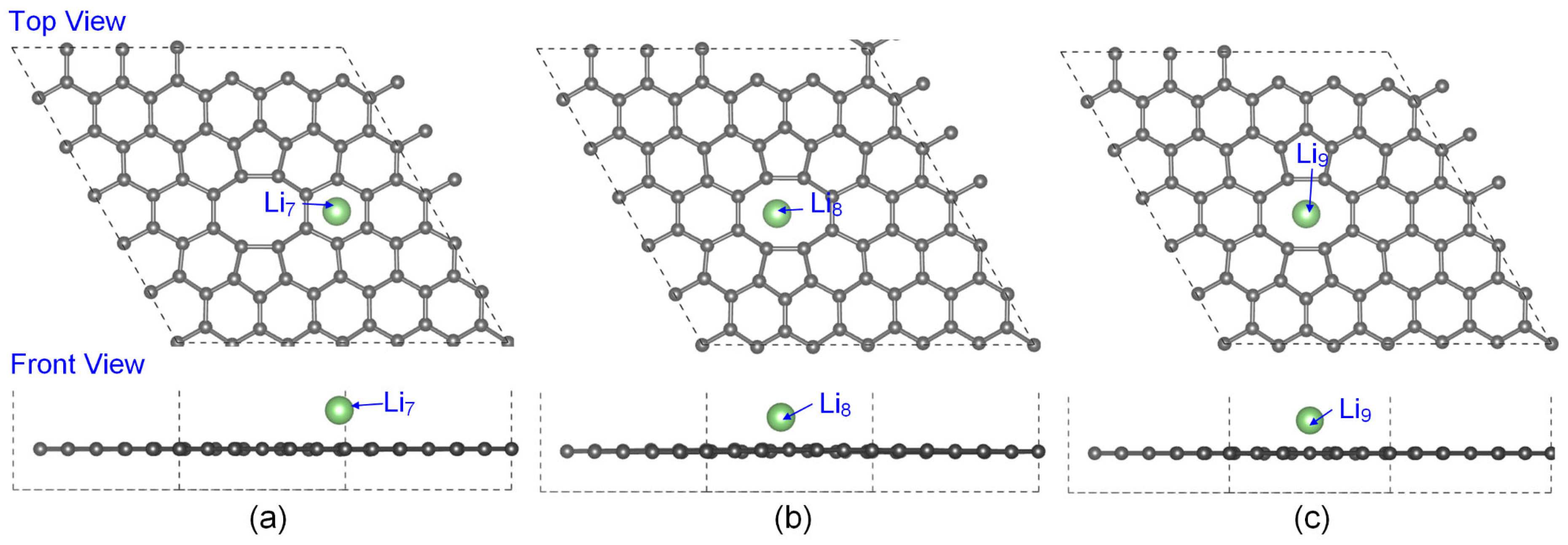

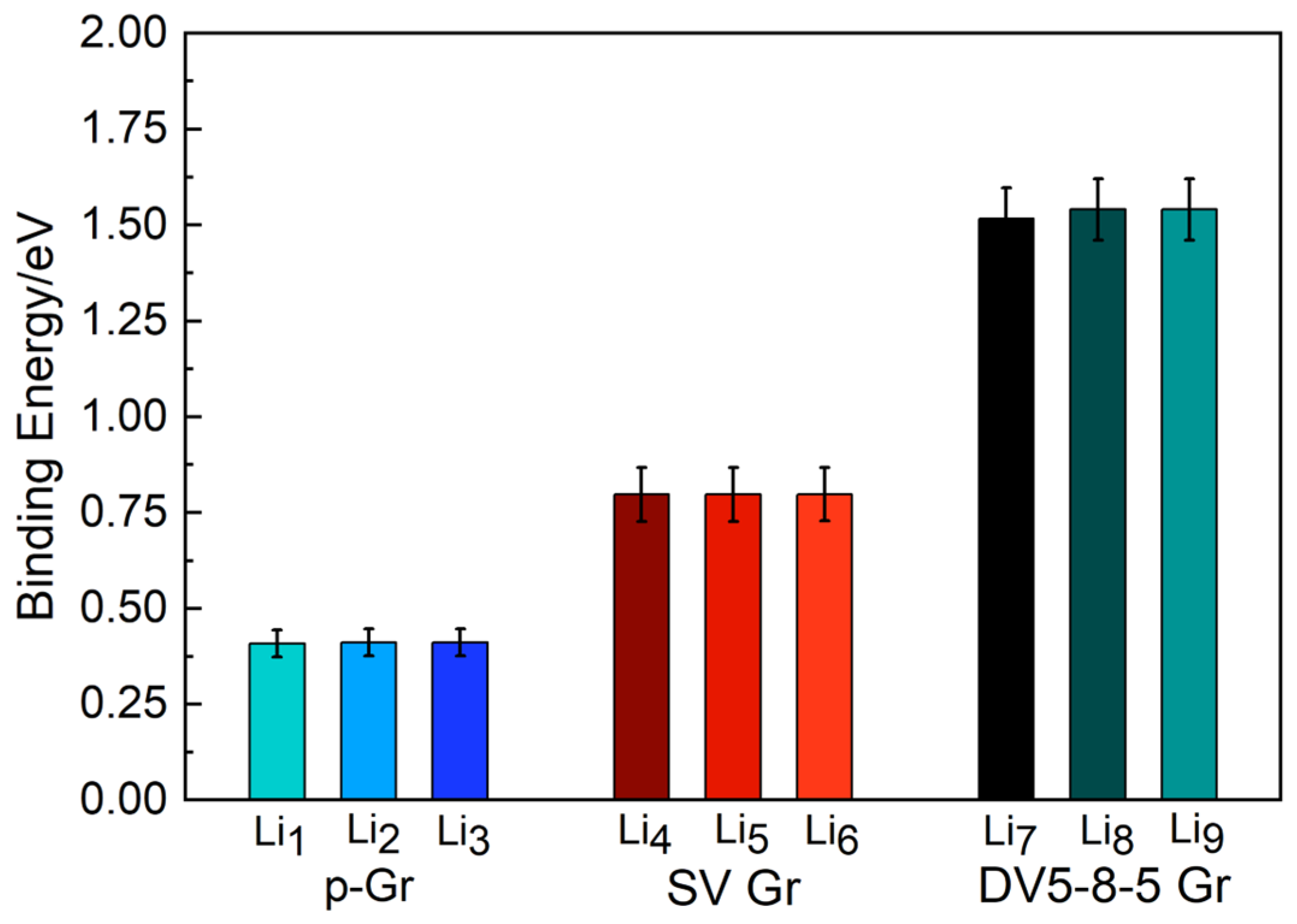

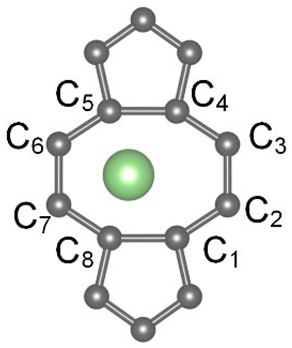

3.1. The Lowest-Energy Li Adsorption Structures and Binding Energy Analysis

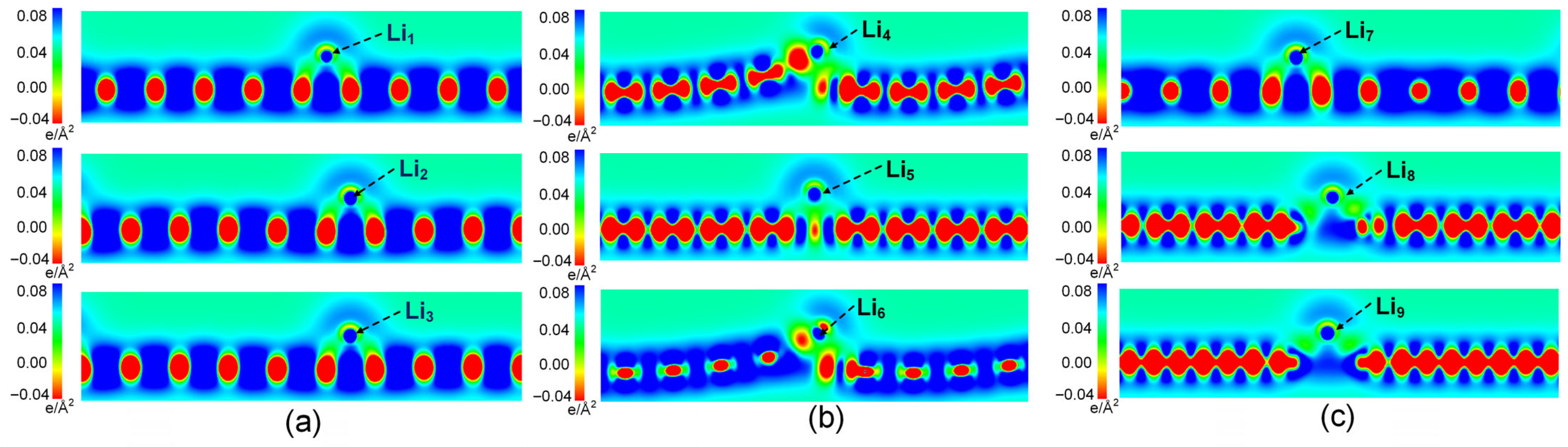

3.2. Charge Density Difference Analysis and Bader Charge Analysis

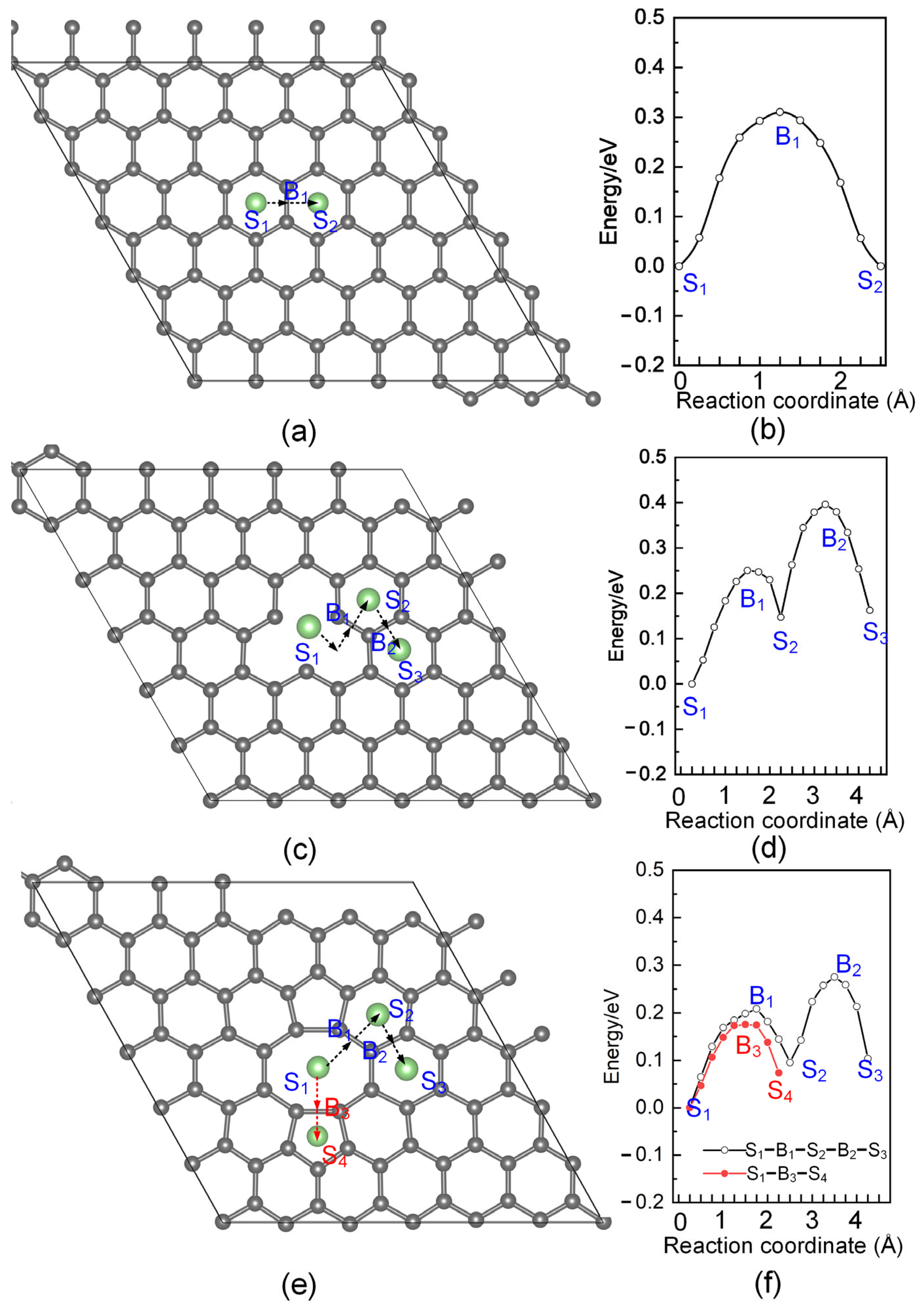

3.3. Diffusion of Li on Different Graphene

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodenough, J.B.; Kim, Y. Challenges for rechargeable Li batteries. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarascon, J.M.; Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 2001, 414, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.N.; Song, B.; Yan, H.J.; Zhang, S.T.; Chen, Q.H. A first-principles study of the lithium insertion behaviors in graphene/Si composites anodes. Comp. Mater. Sci. 2024, 233, 112754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geim, A.K.; Novoselov, K.S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, M.D.; Park, S.; Zhu, Y.; An, J.; Ruoff, R.S. Graphene-based ultracapacitors. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 3498–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Yin, Z.Y.; Wu, S.X.; Qi, X.Y.; He, Q.Y.; Zhang, Q.C.; Yan, Q.Y.; Boey, F.; Zhang, H. Graphene-based materials: Synthesis, characterization, properties, and applications. Small 2011, 7, 1876–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, W.; Lu, W.C.; Xue, X.Y.; Ho, K.M.; Wang, C.Z. Lithium diffusion in silicon encapsulated with graphene. Nanomaterial 2021, 11, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, M.D.; Kim, H.; Kim, G. Various defects in graphene: A review. RSC Adv. 2022, 33, 21520–21547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.N.; Huang, R.; Liu, F.B.; Chen, Q.H.; Ouyang, P.X.; Dou, Z.L. Study on the influence of defective graphene on the Li diffusion performance in Si/defective graphene composite anodes: An ab initio molecular dynamics study. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 19502–19509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.X.; Shen, X.P.; Yao, J.; Park, J.S. Graphene nanosheets for enhanced lithium storage in lithium ion batteries. Carbon 2009, 47, 2049–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.J.; Hou, Z.F.; Wu, L.M. First-principles study of lithium adsorption and diffusion on graphene with point defects. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 21780–21787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.P.; Duan, R.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhu, J. The application of graphene in lithium ion battery electrode materials. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.P.; Lv, W.Q.; Wen, K.C.; He, W.D. Overview of Graphene as Anode in Lithium-ion Batteries. J. Electron. Sci. Technol. 2018, 16, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D.; Wang, S.; Zhao, B.; Wu, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, Z. Li storage properties of disordered graphene nanosheets. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 3136–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xu, S.W.; Li, B.; Yin, M.S.; Shao, F.; Li, H.; Xia, T.; Yang, Z.; Su, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.F.; et al. In-plane defect engineering enabling ultra-stable graphene paper-based hosts for lithium metal anodes. ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 3273–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Gunes, F.; Ta, H.Q.; Lee, S.M.; Chae, S.J.; Sheem, K.Y.; Cojocaru, C.S.; Xie, S.S.; Lee, Y.H. Diffusion Mechanism of Lithium Ion through Basal Plane of Layered Graphene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8646–8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pašti, I.A.; Jovanović, A.; Dobrota, A.S.; Mentus, S.V.; Johansson, B.; Skorodumova, N.V. Atomic adsorption on graphene with a single vacancy: Systematic DFT study through the periodic table of elements. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 20, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, H.; Kinaci, A.; Zhao, Z.J.; Chan, M.K.Y.; Greeley, J.P. First-principles analysis of defect-mediated Li adsorption on graphene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 21141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Yu, X.; Dai, X.; Liu, G.; Chen, G. Large vacancy-defective graphene for enhanced lithium storage. Carbon Trends 2023, 10, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.; Li, J.; Koratker, N.; Shenoy, V.B. Enhanced lithiation in defective graphene. Carbon 2014, 80, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ren, Z.; Guo, P.; Fang, L.; Fan, J. Diffusion of Li+ ion on graphene: A DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 258, 1651–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Hou, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y. First-principles studies of lithium adsorption and diffusion on graphene with grain boundaries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 28055–28062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zheng, W.T.; Kuo, J.L. Adsorption and diffusion of Li on pristine and defective graphene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2432–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 13115–13118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parameterization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Liao, N.B.; Zhang, M.; Xue, W. Lithiation behavior of graphene-silicon composite as high performance anode for lithium-ion battery: A first principles study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 463, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odbadrakh, K.; McNutt, N.W.; Nicholson, D.M.; Rios, O.; Keffer, D.J. Lithium diffusion at Si-C interfaces in silicon-graphene composites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 053906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, K.; Wang, X.; Tao, Z.; Yang, J.; Shu, N.; Ye, J.; Pan, F.; Xie, J.; Tan, Z.; Sun, X.; et al. In Operando Probing of Lithium-Ion Storage on Single-Layer Graphene. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1808091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henkelman, G.; Arnaldsson, A.; Jónsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2006, 36, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, G.; Jónsson, H. Quantum and thermal effects in H2 dissociative adsorption: Evaluation of free energy barriers in multidimensional quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 72, 1124–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthaisar, C.; Barone, V. Edge effects on the characteristics of Li diffusion in graphene. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 2838–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthaisar, C.; Barone, V.; Peralta, J. Lithium adsorption on zigzag graphene nanoribbons. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 113715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | Max Δz of C Atoms (Å) | Avg Δz of C Atoms (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| DV5-8-5 Gr (before Li adsorption) | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| DV5-8-5 Gr (after Li adsorption) | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Nonagon Ring | Bond Length/Å | Before Li Adsorption | After Li Adsorption | Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC1-C2 | 1.388 | 1.409 | 0.021 |

| LC2-C3 | 1.404 | 1.441 | 0.037 | |

| LC3-C4 | 1.404 | 1.430 | 0.025 | |

| LC4-C5 | 1.388 | 1.518 | 0.129 | |

| LC5-C6 | 1.404 | 1.462 | 0.058 | |

| LC6-C7 | 1.389 | 1.518 | 0.129 | |

| LC7-C8 | 1.404 | 1.429 | 0.025 | |

| LC8-C9 | 1.404 | 1.441 | 0.037 | |

| LC9-C1 | 1.389 | 1.409 | 0.020 |

| Octagon Ring | Bond Length/Å | Before Li Adsorption | After Li Adsorption | Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC1-C2 | 1.461 | 1.471 | 0.010 |

| LC2-C3 | 1.462 | 1.463 | 0.001 | |

| LC3-C4 | 1.462 | 1.472 | 0.010 | |

| LC5-C6 | 1.461 | 1.476 | 0.015 | |

| LC6-C7 | 1.462 | 1.465 | 0.003 | |

| LC7-C8 | 1.462 | 1.476 | 0.014 | |

| LC8-C1 | 1.468 | 1.626 | 0.158 | |

| LC4-C5 | 1.468 | 1.627 | 0.159 |

| Different Graphene Structure | Adsorption Sites | ∆QLi | ∆QC |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-Gr | Li1 | +0.893 | −0.783 |

| Li2 | +0.895 | −0.784 | |

| Li3 | +0.894 | −0.784 | |

| SV Gr | Li4 | +0.905 | −0.795 |

| Li5 | +0.905 | −0.796 | |

| Li6 | +0.905 | −0.795 | |

| DV5-8-5 Gr | Li7 | +0.910 | −0.798 |

| Li8 | +0.911 | −0.800 | |

| Li9 | +0.912 | −0.804 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Si, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Huang, R.; Yan, H.; Mu, M.; Liu, F.; Zhang, S. A First-Principles Study of Lithium Adsorption and Diffusion on Graphene and Defective-Graphene as Anodes of Li-Ion Batteries. Coatings 2026, 16, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010052

Si L, Yang Y, Wang Y, Wu Q, Huang R, Yan H, Mu M, Liu F, Zhang S. A First-Principles Study of Lithium Adsorption and Diffusion on Graphene and Defective-Graphene as Anodes of Li-Ion Batteries. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleSi, Lina, Yijian Yang, Yuhao Wang, Qifeng Wu, Rong Huang, Hongjuan Yan, Mulan Mu, Fengbin Liu, and Shuting Zhang. 2026. "A First-Principles Study of Lithium Adsorption and Diffusion on Graphene and Defective-Graphene as Anodes of Li-Ion Batteries" Coatings 16, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010052

APA StyleSi, L., Yang, Y., Wang, Y., Wu, Q., Huang, R., Yan, H., Mu, M., Liu, F., & Zhang, S. (2026). A First-Principles Study of Lithium Adsorption and Diffusion on Graphene and Defective-Graphene as Anodes of Li-Ion Batteries. Coatings, 16(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010052