Analysis of Failure Characteristics and Mechanisms of Asphalt Pavements for Municipal Landscape Roads

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

2.1. Pavement Distress Data Collection and Preprocessing

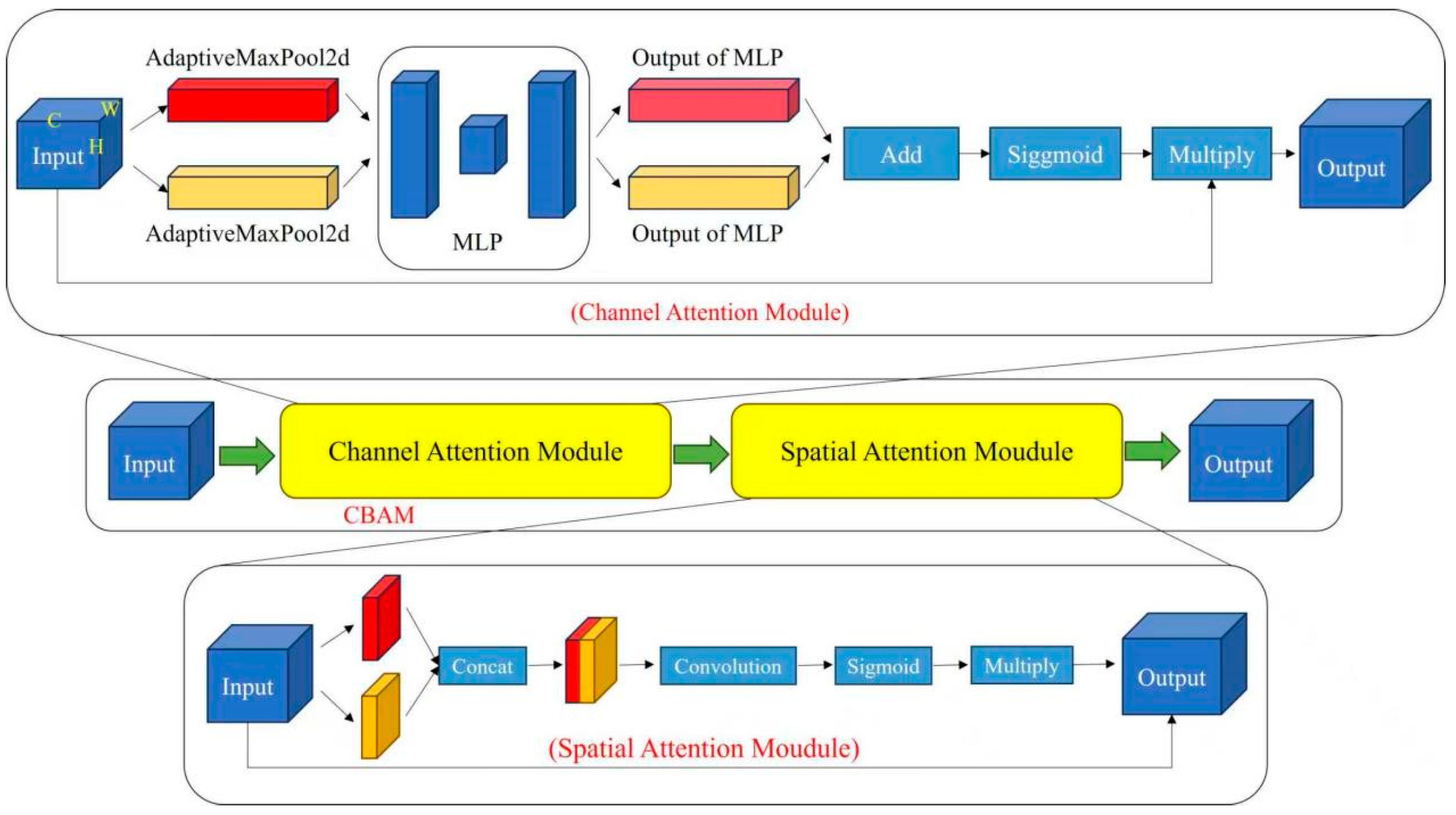

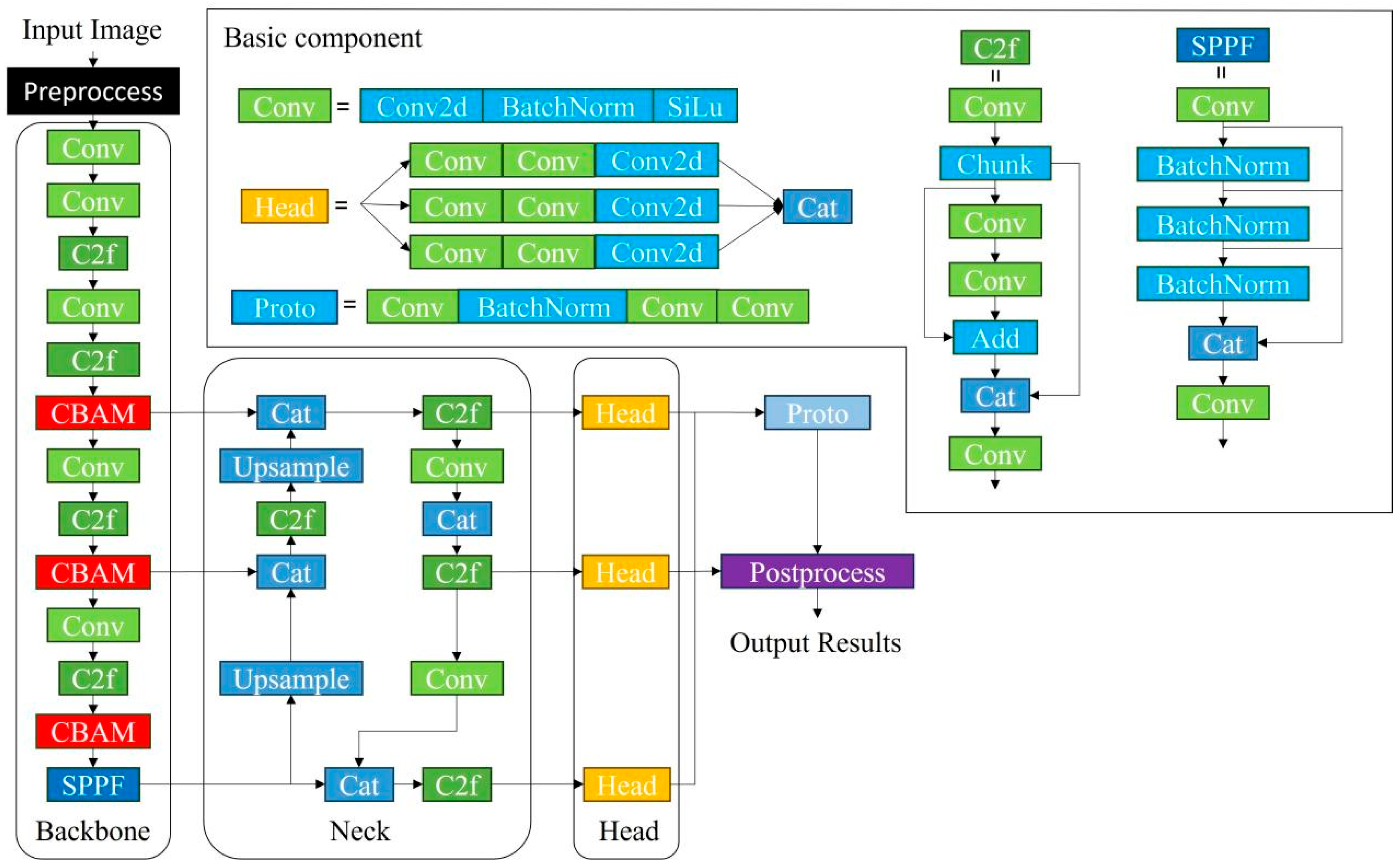

2.2. Pavement Distress Identification Methods

2.3. Materials and Aging Simulation

2.4. Materials Testing Methods

2.4.1. Rheological Performance Tests of Asphalt Binder

2.4.2. Low-Temperature Cracking Resistance Test of Asphalt Mixtures

2.4.3. Freeze-Thaw Durability Test of Asphalt Mixtures

3. Results and Analysis

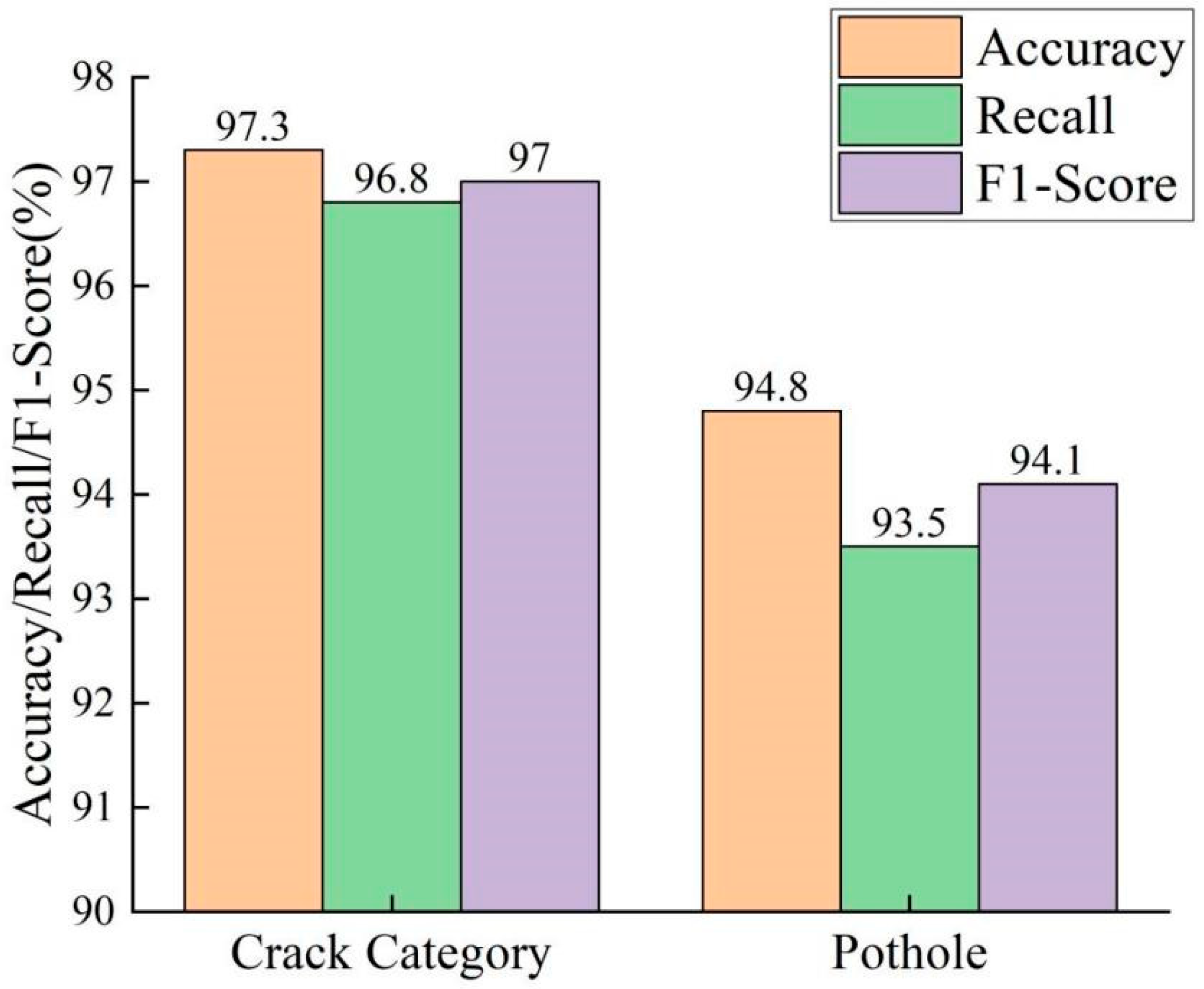

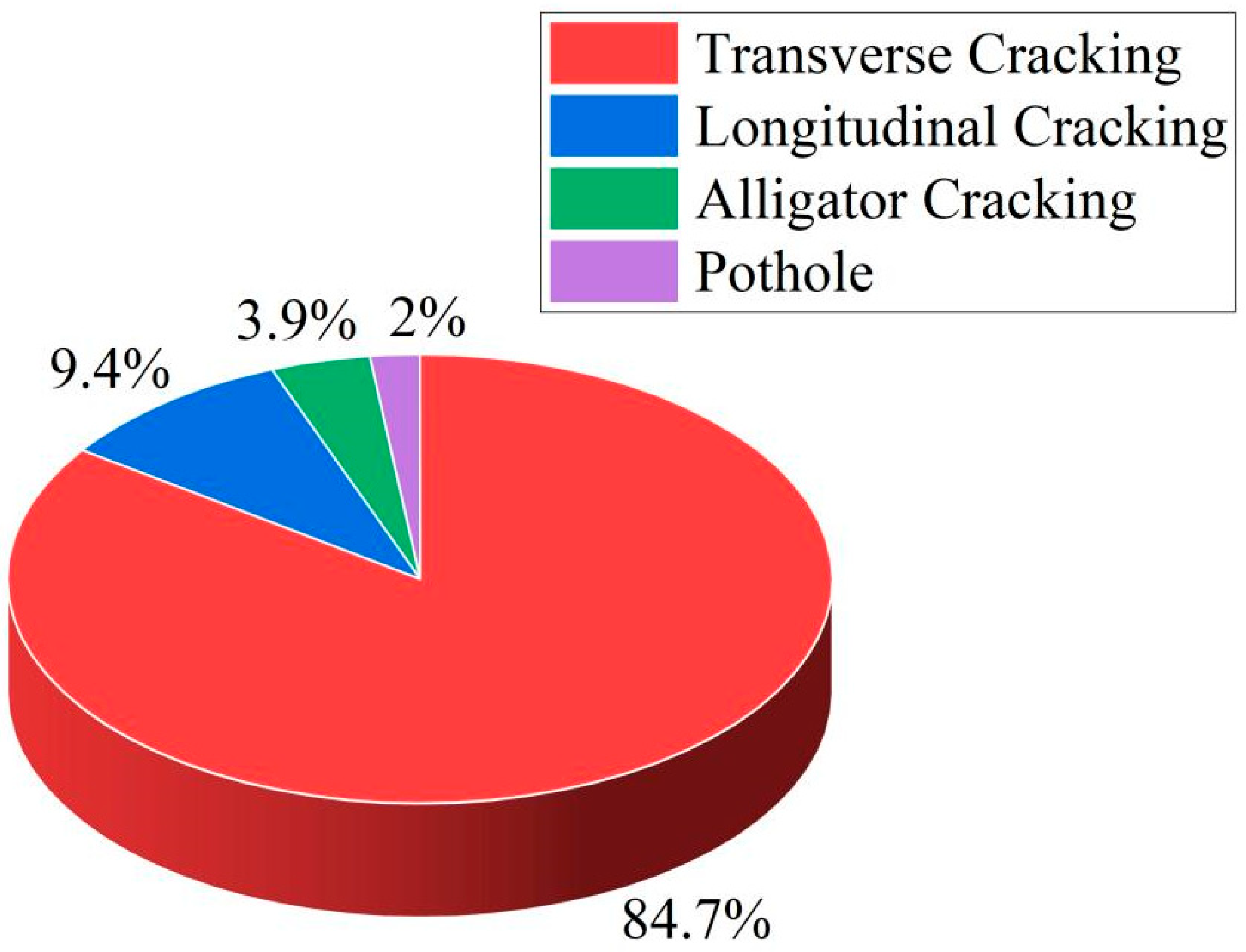

3.1. Distress Identification Accuracy and Distribution Characteristics

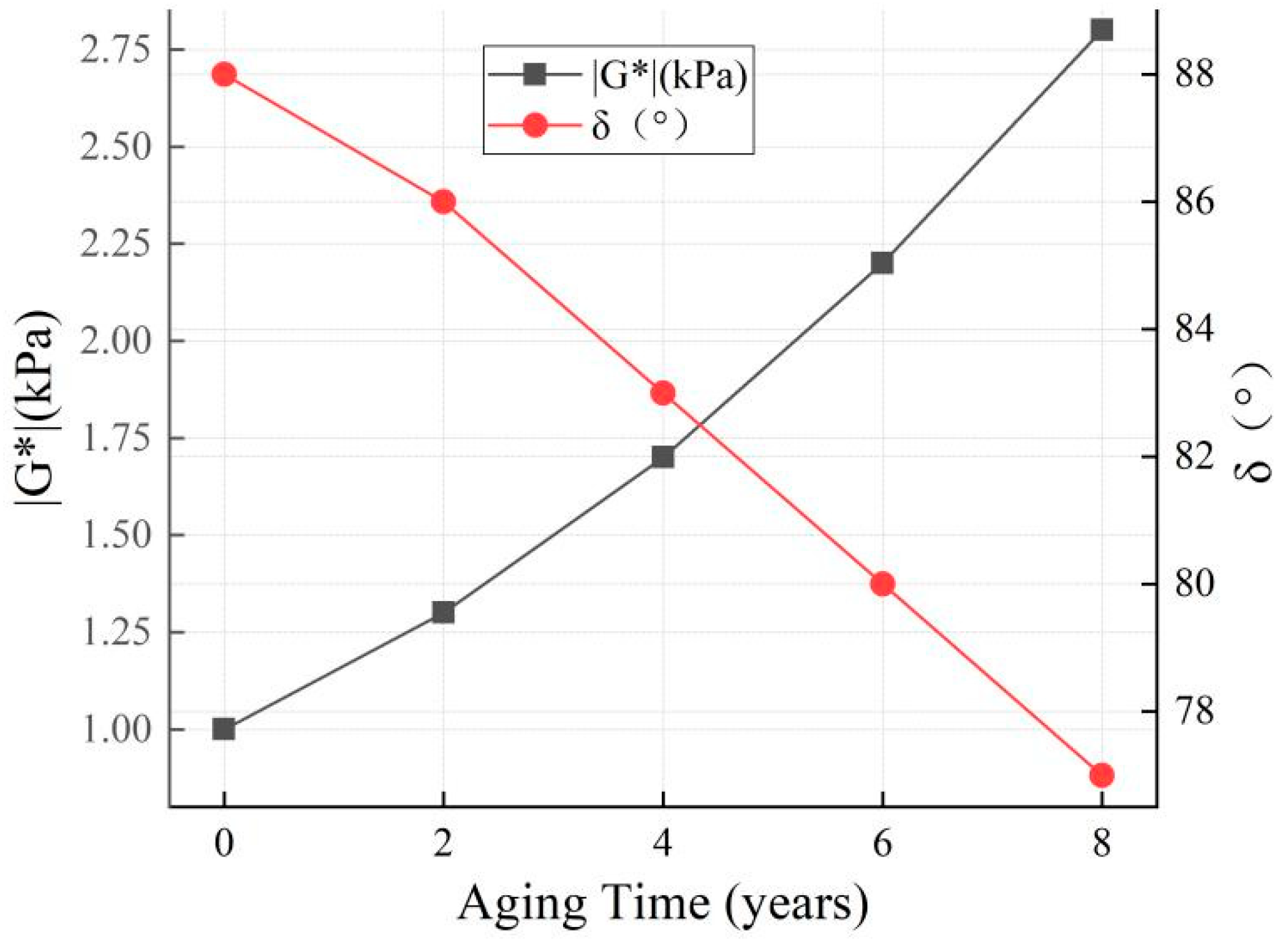

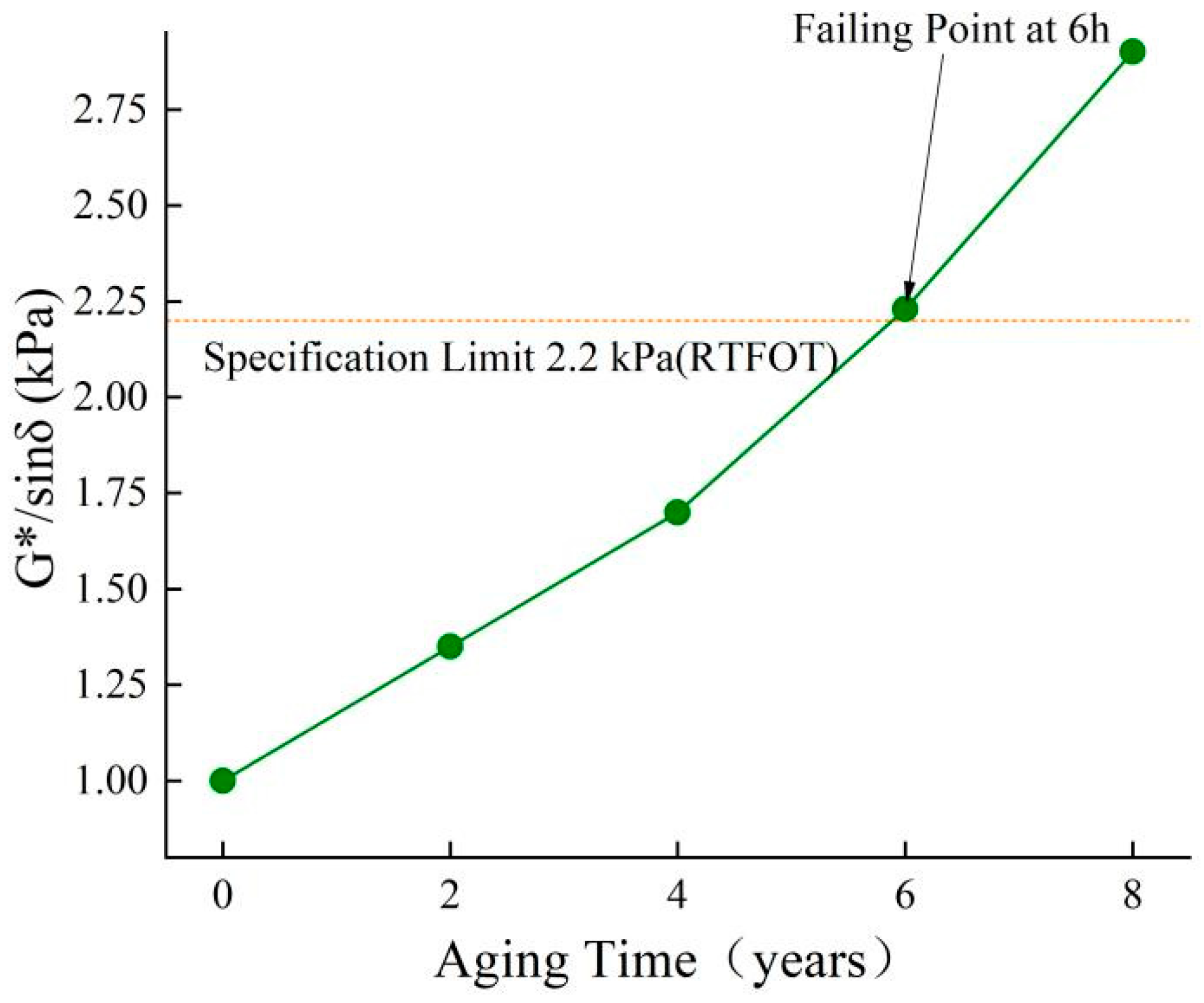

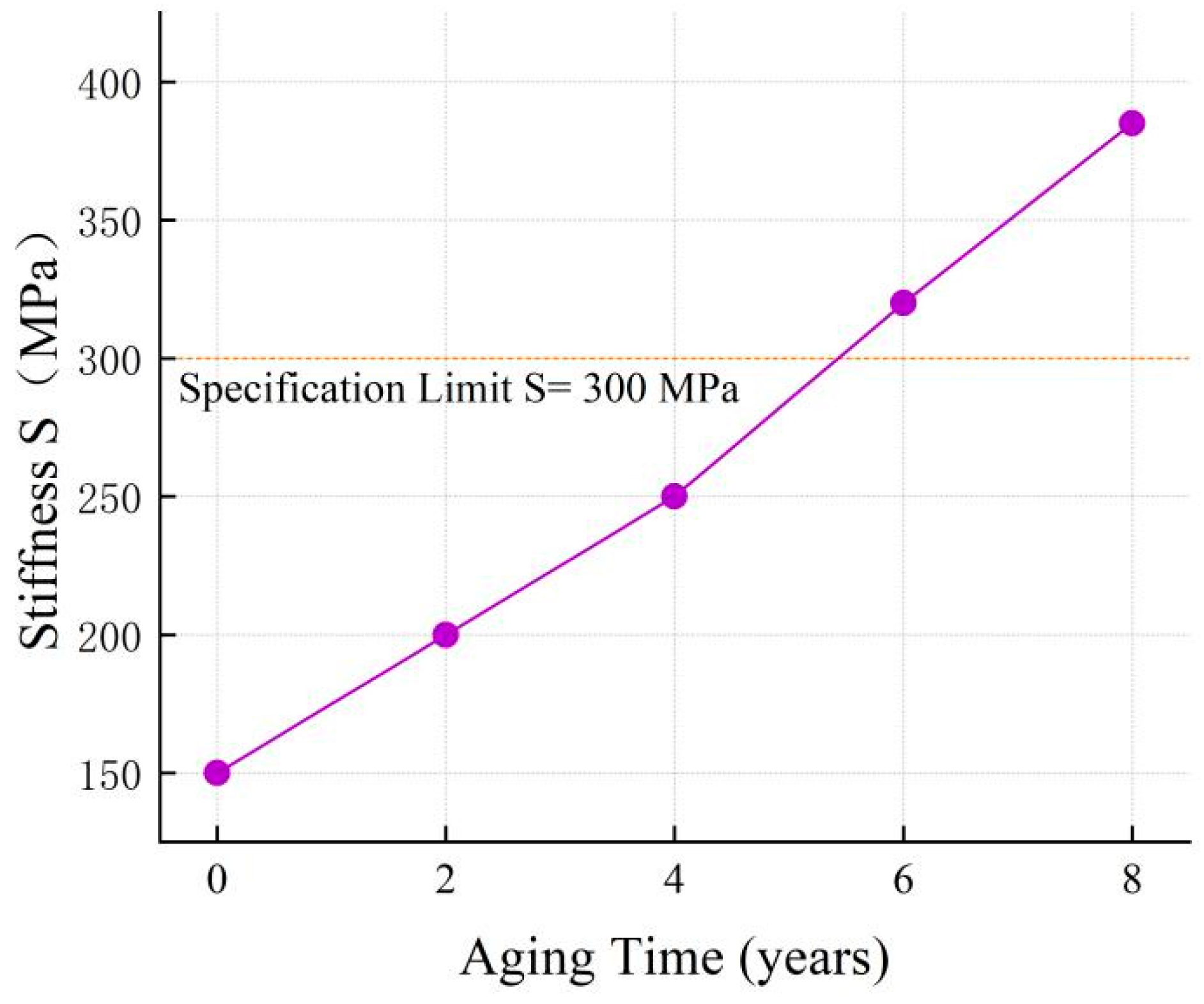

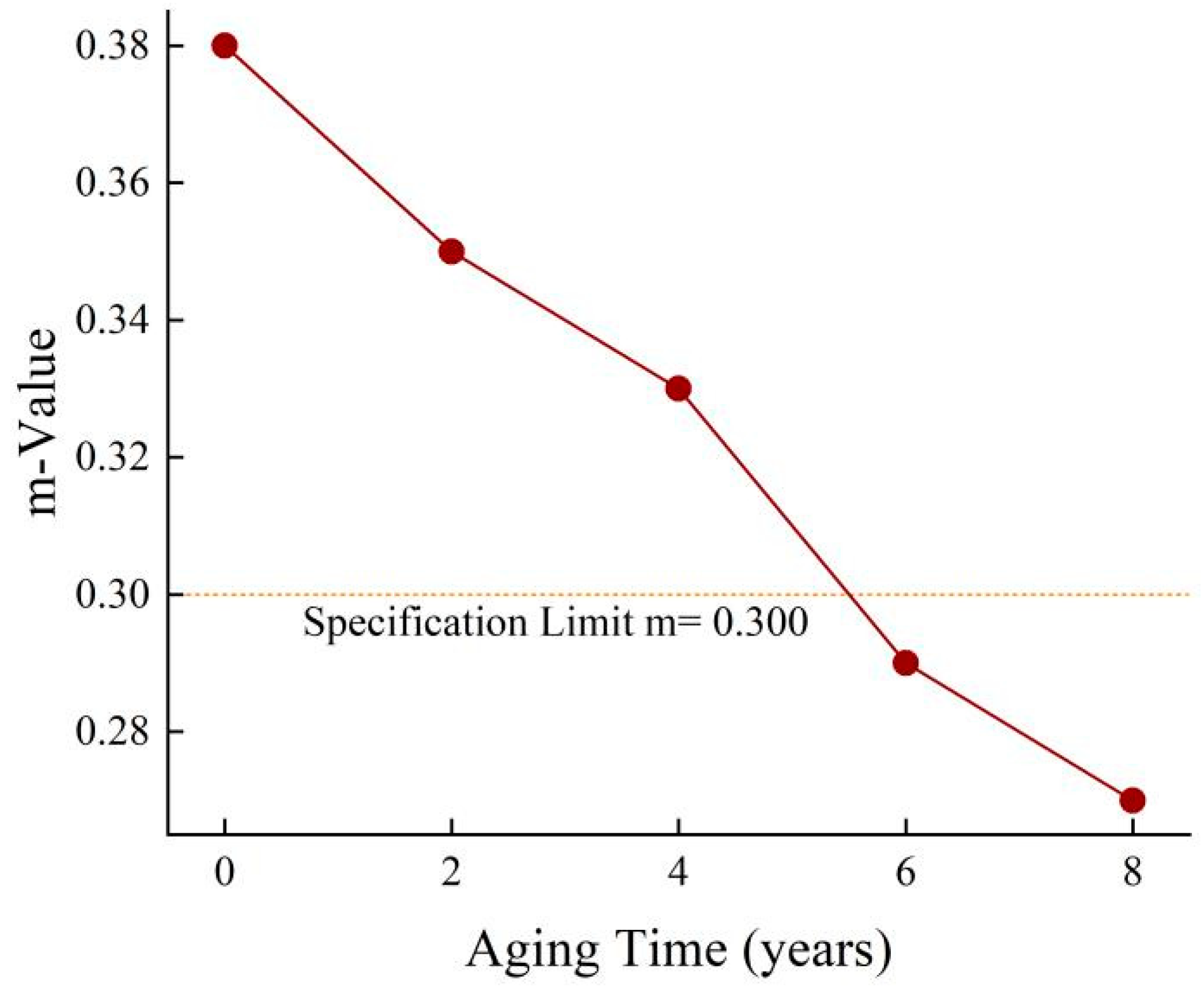

3.2. Rheological Properties of Asphalt After Aging

3.3. Low-Temperature Crack Resistance of Asphalt Mixtures with Different Aging Degrees

3.4. Freeze-Thaw Cycle Performance of Asphalt with Different Aging Degrees

4. Conclusions and Future Work

- Through the identification and analysis of distresses in asphalt pavements of municipal landscape roads, this study found that transverse cracks are the most common type of pavement distress. The formation of transverse cracks is closely related to environmental factors such as asphalt aging, temperature fluctuations, and moisture intrusion. Specifically, asphalt aging causes the material to harden and become brittle, leading to a significant decrease in its low-temperature crack resistance. Meanwhile, temperature differences and freeze-thaw action further accelerate the propagation of cracks. The study shows that transverse cracks account for 72% of the total number of cracks, making them the most common and most destructive type of distress in municipal landscape road pavements.

- Tree shadows on landscape roads are a key factor affecting the accuracy of pavement distress identification. To address this issue, the SpA-Former shadow removal network was proposed in this study, which effectively eliminates tree shadow interference in images and significantly enhances the contrast of distress areas. It is shown by the experimental results that after applying this technology, the grayscale contrast of distress areas is improved by 40%–60%, which enhances the accuracy of distress detection and provides effective technical support for intelligent distress detection.

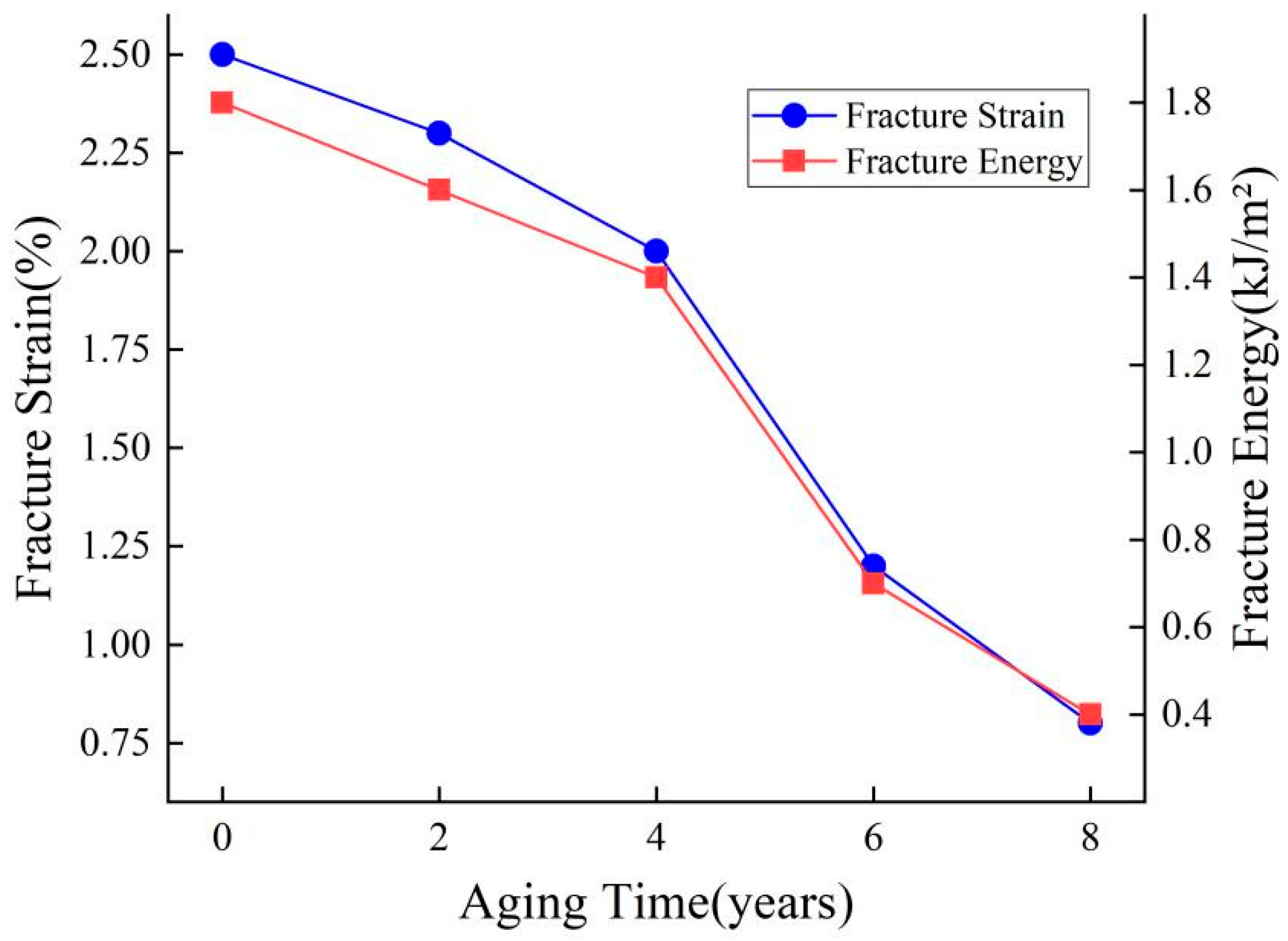

- Through indoor aging simulation experiments, it was found in this study that the low-temperature crack resistance of asphalt decreases significantly during the aging process. Specifically, the fracture strain decreases from 2.5% to 0.5%, and the fracture energy drops from 1.8 kJ/m2 to 0.4 kJ/m2. As the asphalt ages, its ductility decreases and brittleness increases, causing it to be more prone to cracking in low-temperature environments. This aging process gradually makes the asphalt lose its flexibility. Especially under low-temperature conditions, the probability of cracking increases significantly.

- It is shown by the study that the stiffness of asphalt increases significantly as the aging duration extends. Specifically, the stiffness increases from 50 MPa at 0 years of aging to 320 MPa at 8 years of aging, which far exceeds the standard limit of 300 MPa. The increase in asphalt stiffness enhances its deformation resistance; however, it also makes the asphalt material more brittle in low-temperature environments, rendering it prone to cracking. During the aging process, the asphalt gradually hardens and loses its original flexibility. As a result, it is more likely to undergo brittle fracture under stresses such as thermal expansion and contraction, which further accelerates the formation of transverse cracks.

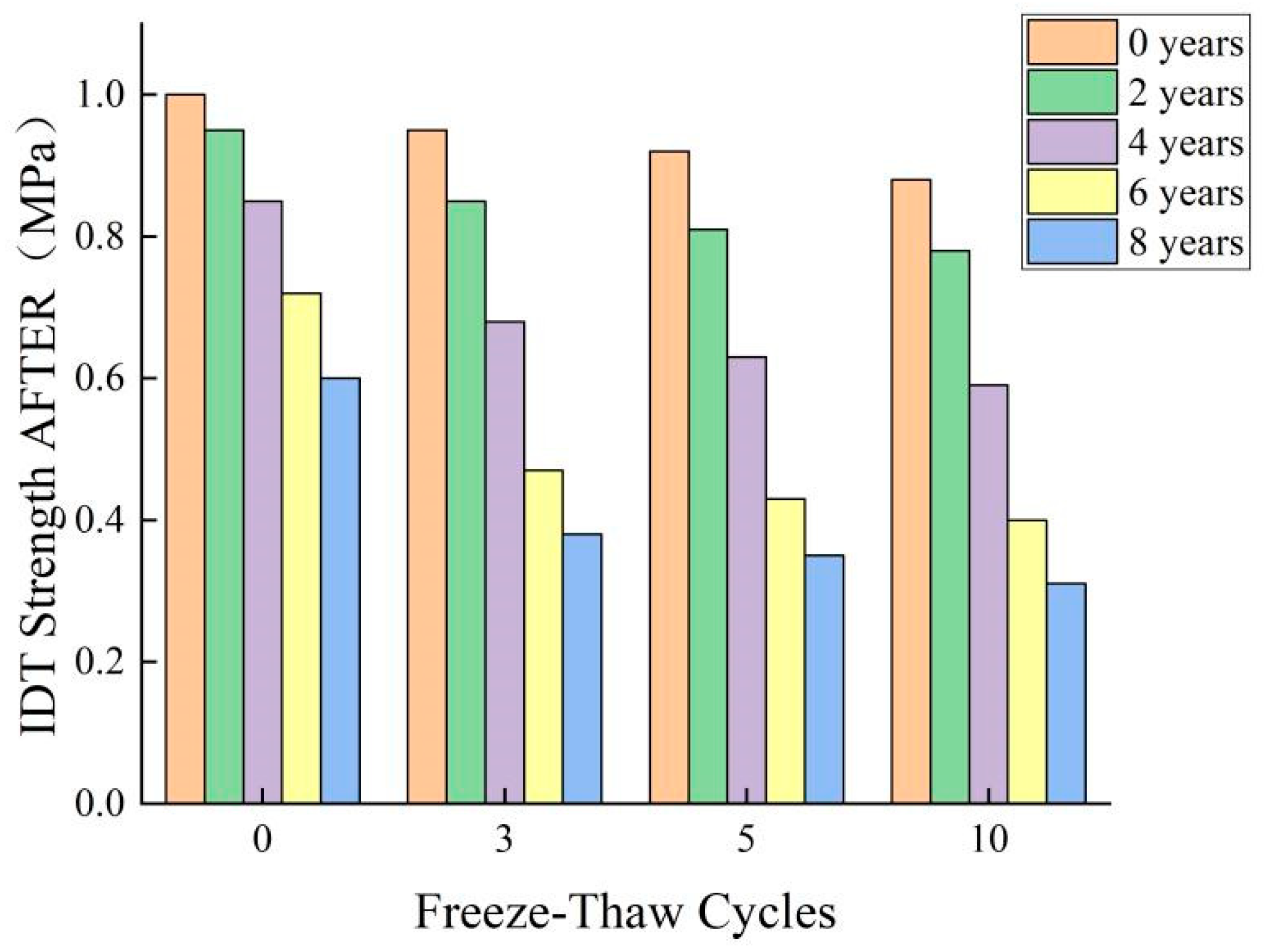

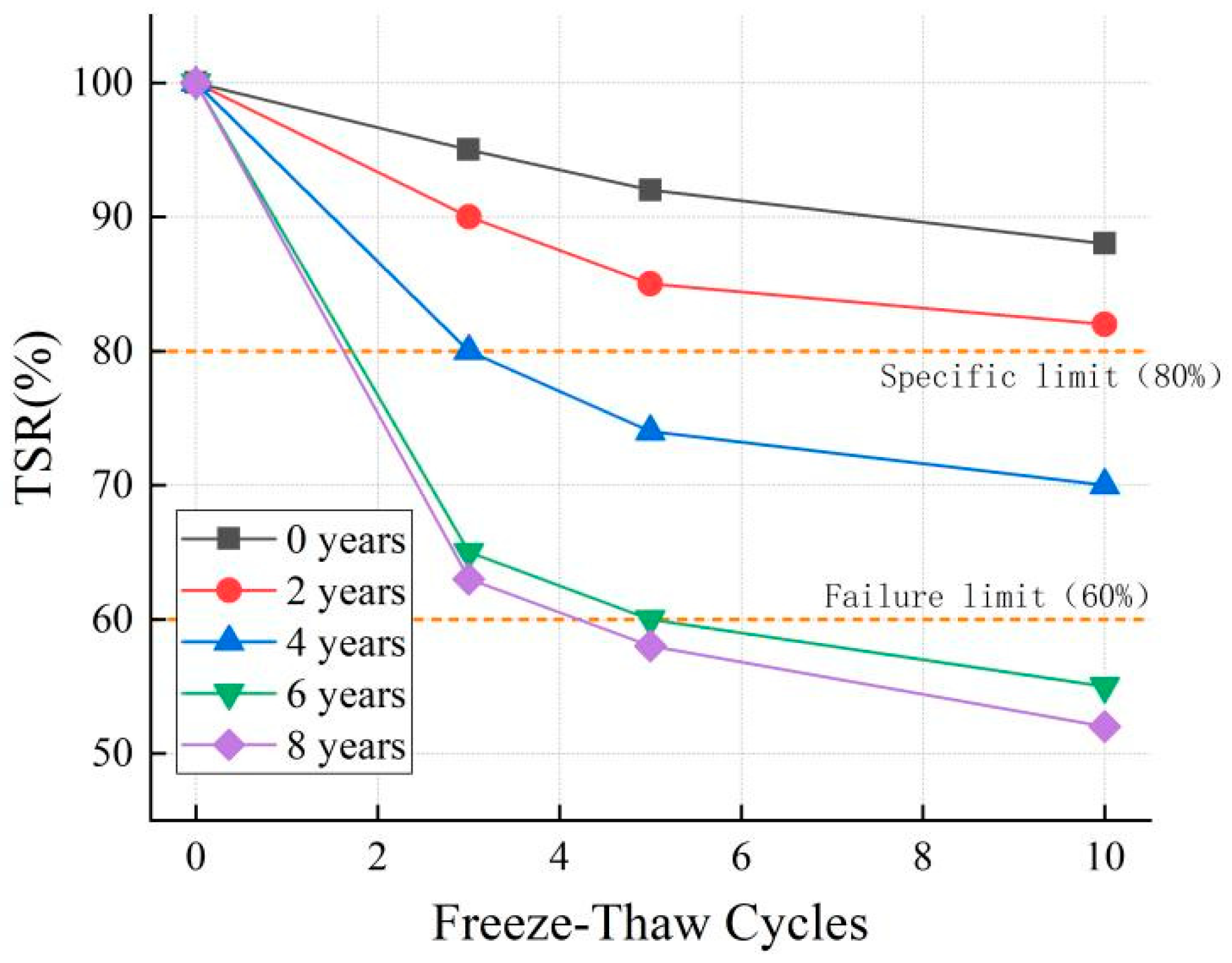

- The impact of freeze-thaw cycles on the freeze-thaw resistance of asphalt mixtures with different aging durations was analyzed in this study. Results show that as the aging duration of asphalt increases, its freeze-thaw resistance decreases significantly. Specifically, for unaged asphalt (0 years of aging), the TSR (Tensile Strength Ratio) remains above 80% even after 10 freeze-thaw cycles. In contrast, for asphalt aged for 6 and 8 years, the TSR drops to below 60% after only 3 freeze-thaw cycles, showing a significant reduction in freeze-thaw resistance. Meanwhile, the IDT (Indirect Tensile Strength) also decreases gradually with the increase in the number of freeze-thaw cycles. Especially for asphalt aged for more than 6 years, its freeze-thaw resistance is almost lost, indicating that the performance of the asphalt material has severely degraded and its resistance to freeze-thaw damage has been greatly weakened.

- As the starting point of a series of studies, future work will deepen along three directions: First, expanding to the structural scale by constructing composite pavement specimens incorporating different base layers (e.g., semi-rigid, flexible) and considering interlayer bonding, to quantify the influence of base restraint and structural integrity on cracking behavior through mechanical testing and simulation. Second, broadening the spectrum of influencing factors by systematically studying the interactive effects of variable traffic loads, extreme climatic conditions, and different asphalt chemical compositions (e.g., modified asphalt, high RAP content) on aging pathways and failure modes, based on the established temperate climate benchmark, to enhance the universality of the conclusions. Third, promoting engineering application validation by conducting long-term performance monitoring and full-scale testing for the proposed preventive maintenance window (years 5–6) and the use of softer asphalt (e.g., penetration grade 90). Through comparative road section studies, the actual benefits of delaying cracking and extending service life will be quantified, ultimately forming operable design and maintenance guidelines to translate material mechanism discoveries into engineering practice.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, S.; Park, H.; Baek, C. Fatigue Cracking Characteristics of Asphalt Pavement Structure under Aging and Moisture Damage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rys, D.; Jaczewski, M.; Pszczola, M.; Kamedulska, A.; Kamedulski, B. Factors affecting low-temperature cracking of asphalt pavements: Analysis of field observations using the ordered logistic model. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picos, K.; DiazRamírez, V.H.; Tapia, J.J. A roadmap to global illumination in 3D scenes: Solutions for GPU object recognition applications. In Proceedings of the SPIE Optical Engineering + Applications, San Diego, CA, USA, 17–21 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Yao, Y.; Li, J.; Qian, J.; Liu, L. Research on lightweight GPR road surface distress image recognition and data expansion algorithm based on YOLO and GAN. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02789. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Li, P. Shadow-aware image colorization. Vis. Comput. 2024, 40, 4969–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, A.; Benedetto, J.F. A real-time automatic pavement crack and pothole recognition system for mobile Android-based devices. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 33, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, W. Recognition of the Typical Distress in Concrete Pavement Based on GPR and 1D-CNN. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Cheng, C.; Lv, H. Automatic identification of pavement cracks in public roads using an optimized deep convolutional neural network model. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2023, 381, 20220147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Bei, Z.; Ling, T.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, L. Research on high-precision recognition model for multi-scene asphalt pavement distresses based on deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25416. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, M.A.; Gyamfi, Y.A. Generative adversarial network for real-time identification and pixel-level annotation of highway pavement distresses. Autom. Constr. 2025, 158, 105213. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.H.R.; Kumar, S.V. Terrestrial LiDAR derived 3D point cloud model, digital elevation model (DEM) and hillshade map for identification and evaluation of pavement distresses. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mivehchi, M.; Wen, H.; Wen, Y.; Wang, L. Study of Measures to Design Asphalt Mixes Including High Percentages of Recycled Asphalt Pavement and Recycled Asphalt Shingles. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Gong, M.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, S.; Fan, J.; Xu, Z.; Hong, J. In situ mechanical response characteristics of Autonomous Rail Rapid Transit (ART) applied to semi-flexible asphalt pavements. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2024, 25, 2644–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goli, H.; Latifi, M.; Sadeghian, M. Comparing the Effect of Moisture on Different Fatigue and Cracking Behaviors of RAP-WMA. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2023, 149, 04023034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Xu, K.; Song, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhang, J. Investigation of cracking behavior in asphalt pavement using digital image processing technology. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1324567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, T. Effect of Asphalt Pavement Base Layers on Transverse Shrinkage Cracking Characteristics. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krami, K.; Benamara, A.; Radouani, M.; Ettayeb, M.; Tarik, L. Study of Asphalt Pavement Cracking in Different Road Sections of Morocco Using Electrical Resistivity Tomography. Int. J. Geophys. 2024, 2024, 6683254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Yao, X.; Du, X. Low temperature cracking behavior of asphalt binders and mixtures: A review. J. Road Eng. 2023, 3, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, S.; Zhu, L.; Liu, T. Temperature variations and frozen zone migration: Assessing the influence of climate change on fatigue cracking in roadway asphalt pavements. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2025, 26, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Li, Y.; Cheng, P.; Chen, X.; Cheng, A. Low-Temperature Cracking and Improvement Methods for Asphalt Pavement in Cold Regions: A Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, C.; Lu, C.; Zhu, S. SpA-Former: An Effective and lightweight Transformer for image shadow removal. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Gold Coast, Australia, 18–23 June 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Qin, H.; Ming, P.; Fang, T.; Zeng, J. An End-to-End Particle Gradation Detection Method for EarthRockfill Dams from Images Using an Enhanced YOLOv8-Seg Model. Sensors 2025, 25, 4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, W.; Liu, J. An Improved YOLOv8 Model for Lotus Seedpod Instance Segmentation in the Lotus Pond Environment. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhou, J.L.; Qian, X.; Fu, S. Method for Identifying the Severity of Wheat Scab in the Field Based on AR Glasses and Improved YOLOv8m-seg. J. Agric. Big Data 2024, 6, 497–508. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Peng, T. Transverse crack patterns of long-term field asphalt pavement constructed with semi-rigid base. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2024, 17, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Tong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, T.; Zhang, J. Numerical analysis of the initiation cause of the surface transverse cracks in semirigid asphalt pavement. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2023, 149, 04023034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; You, Z. A combinational prediction model for transverse crack of asphalt pavement. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 2051–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Ong, G.P.; Wang, Y.; Lu, J. Effects of transverse cracks on the backcalculated layer properties of asphalt pavements from non-destructive testing data. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2023, 42, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input Data Type | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | Improvement (mAP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original mages (with shadows) | 88.2 | 85.8 | 86.5 | - |

| Processed mages (Shadow Removal) | 97.1 | 96.3 | 96.2 | +9.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Cao, X.; Mei, X.; Fu, X.; Zhang, H. Analysis of Failure Characteristics and Mechanisms of Asphalt Pavements for Municipal Landscape Roads. Coatings 2026, 16, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010028

Zhang L, Cao X, Mei X, Fu X, Zhang H. Analysis of Failure Characteristics and Mechanisms of Asphalt Pavements for Municipal Landscape Roads. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lei, Xinxin Cao, Xuefeng Mei, Xinhui Fu, and Huanhuan Zhang. 2026. "Analysis of Failure Characteristics and Mechanisms of Asphalt Pavements for Municipal Landscape Roads" Coatings 16, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010028

APA StyleZhang, L., Cao, X., Mei, X., Fu, X., & Zhang, H. (2026). Analysis of Failure Characteristics and Mechanisms of Asphalt Pavements for Municipal Landscape Roads. Coatings, 16(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010028