Aluminium-Doped Zinc Oxide Thin Films Fabricated by the Aqueous Spray Method and Their Photocatalytic Activities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. The Synthesis of Ammonium Aluminium Oxalate Complex

2.3. Preparation of the Precursor Solutions

2.4. Fabrication of Thin Films by Spray-Coating and Heat Treating

2.5. Measurements

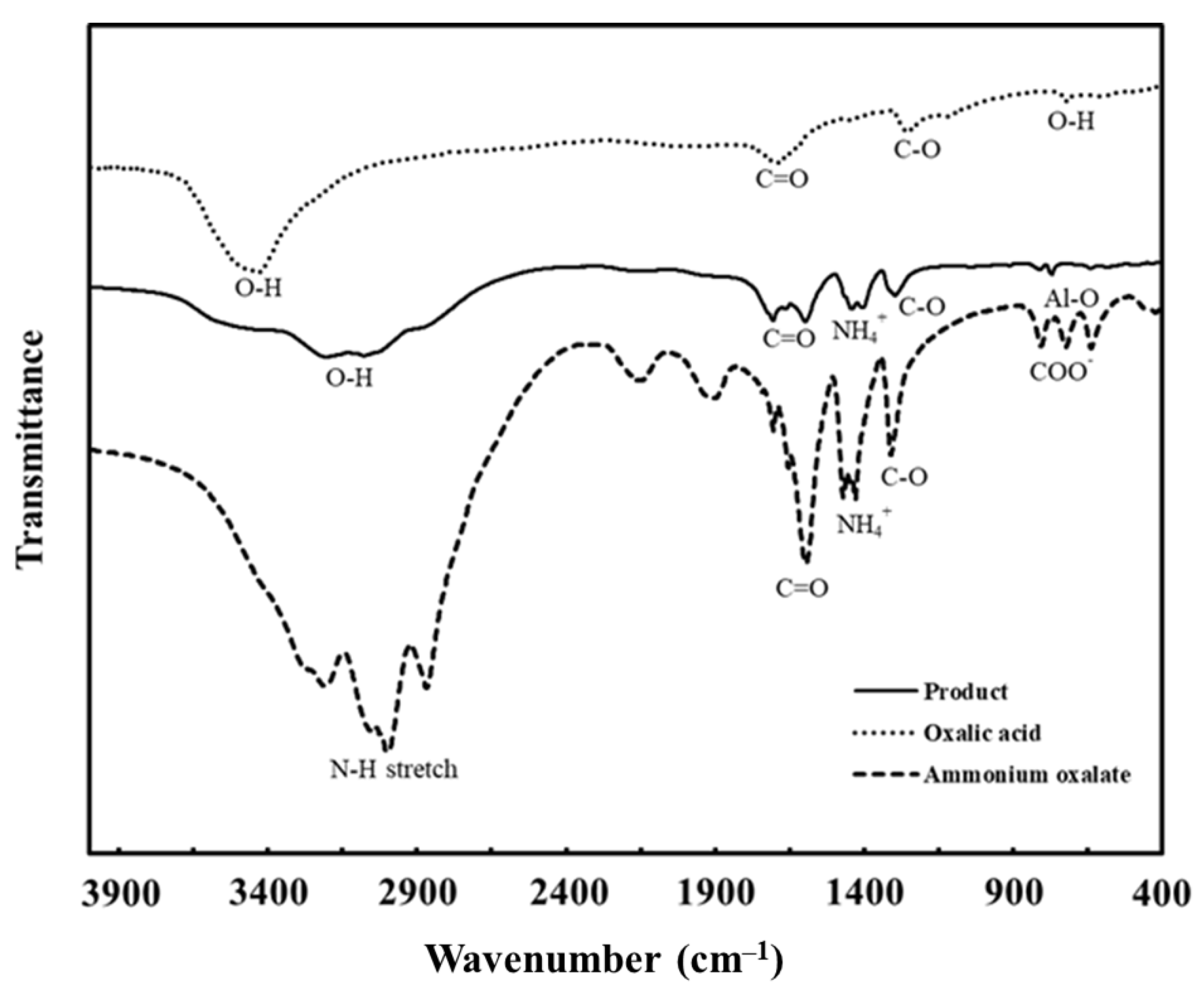

2.5.1. FTIR Analysis of Ammonium Aluminium Oxalate Complex

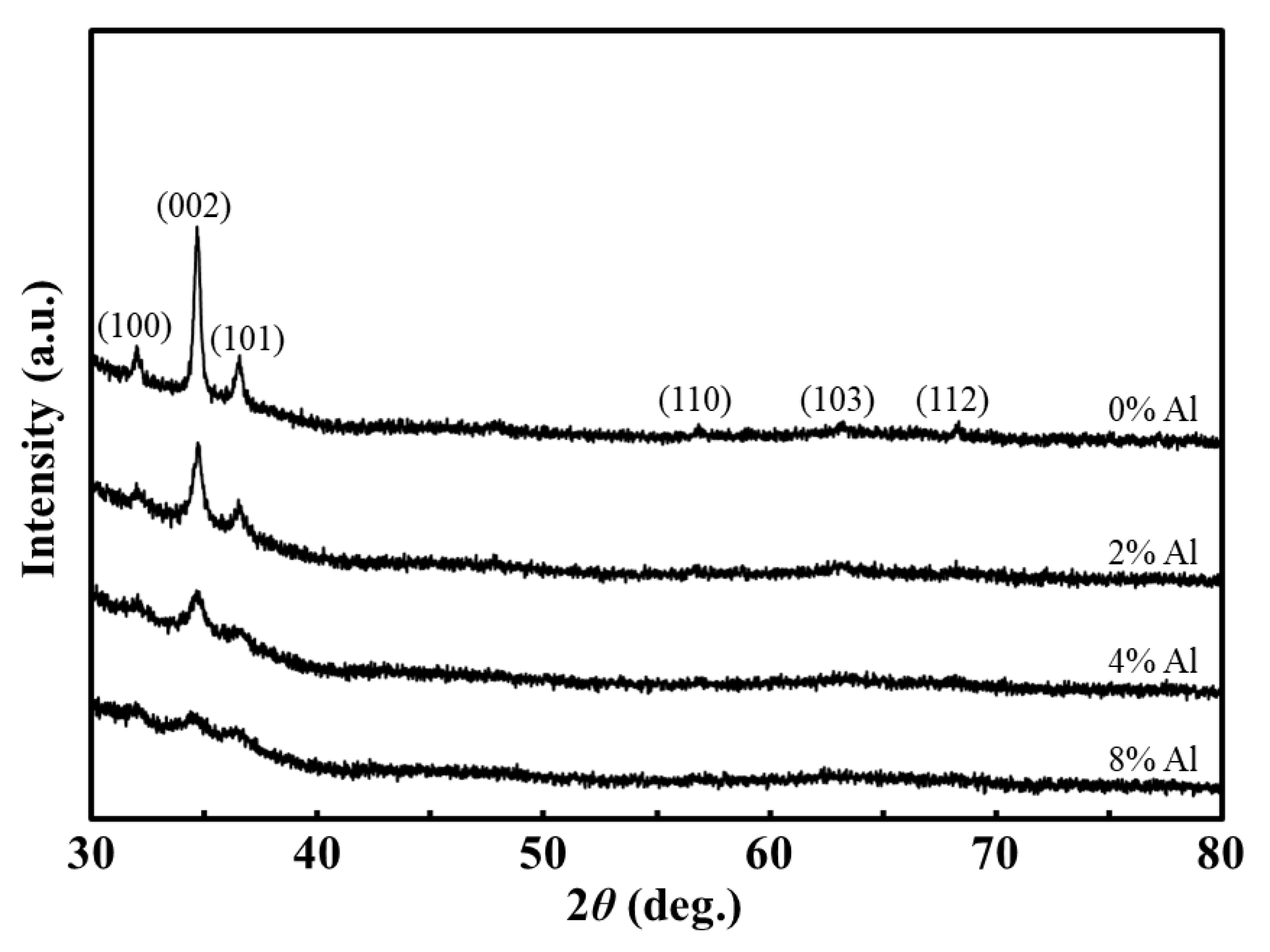

2.5.2. Structural Properties of the Fabricated Thin Films

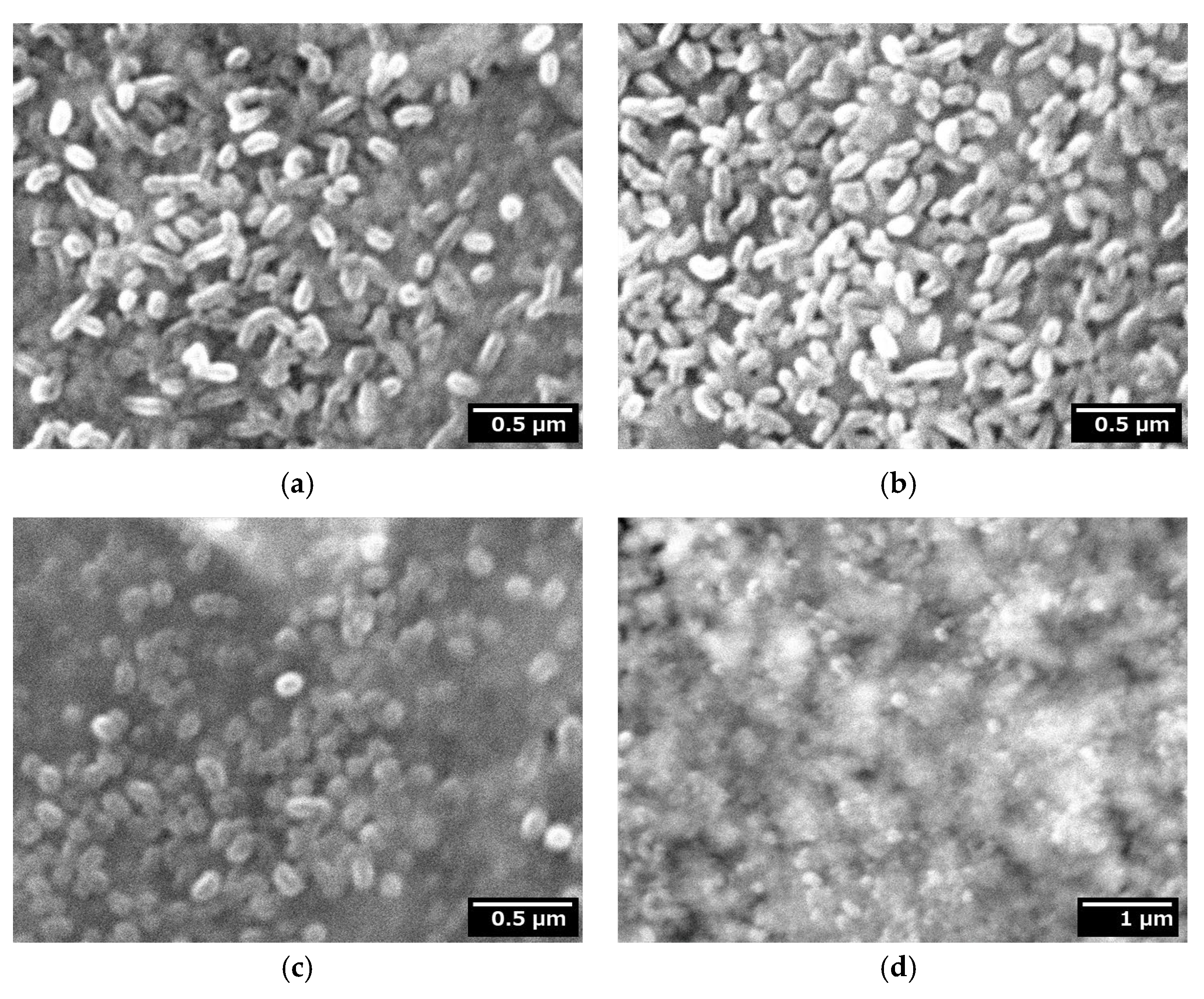

2.5.3. Surface Morphologies of the Fabricated Thin Films

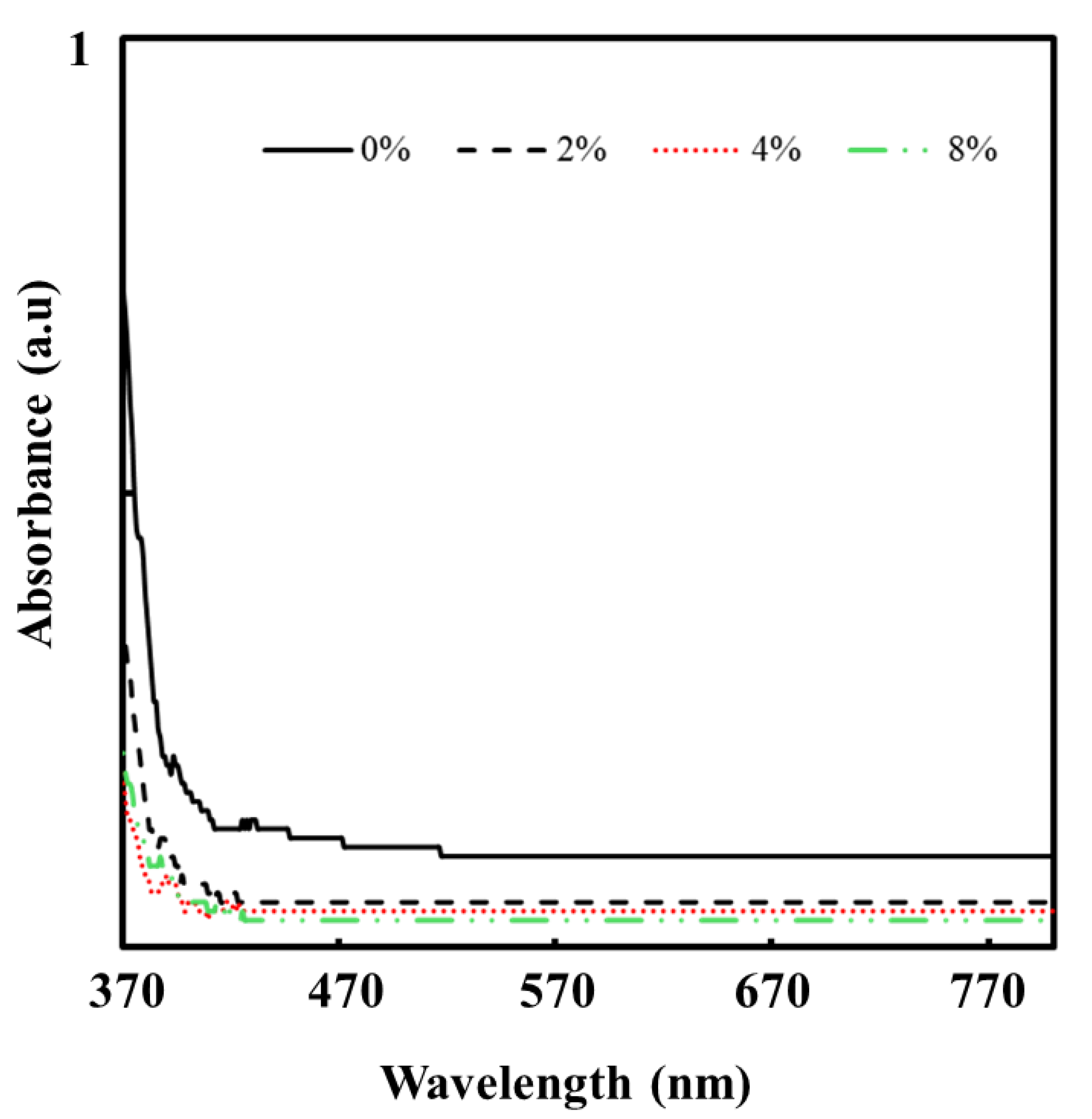

2.5.4. Optical Properties of the Fabricated Thin Films

2.5.5. Photocatalytic Activity Evaluations

3. Results

3.1. FTIR Results for Ammonium Aluminium Oxalate Complex

3.2. Structural Properties of the Fabricated Thin Films

3.3. Surface Morphologies of the Fabricated Thin Films

3.4. Optical Properties of the Fabricated Thin Films

3.4.1. Absorbance

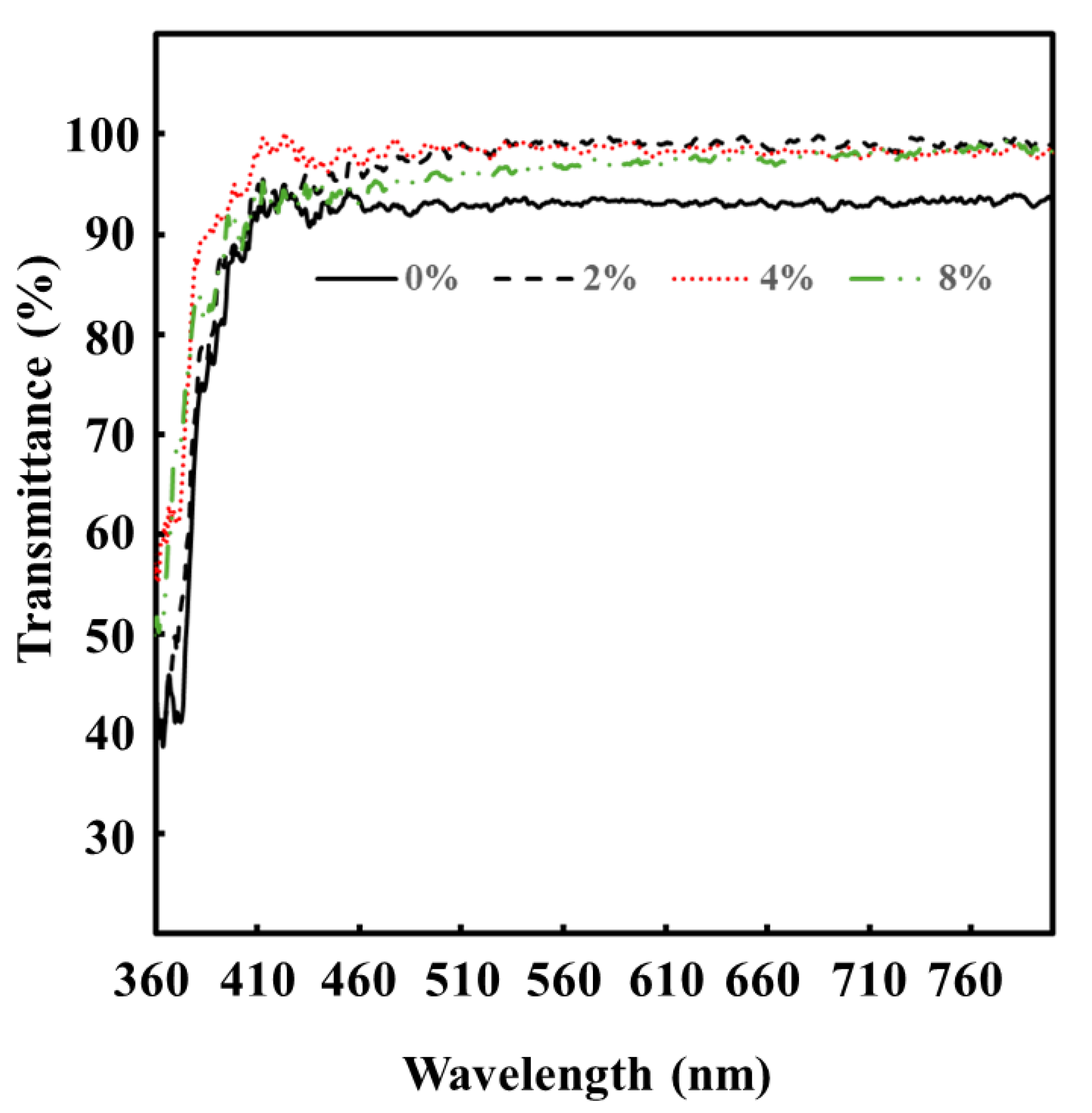

3.4.2. Transmittance

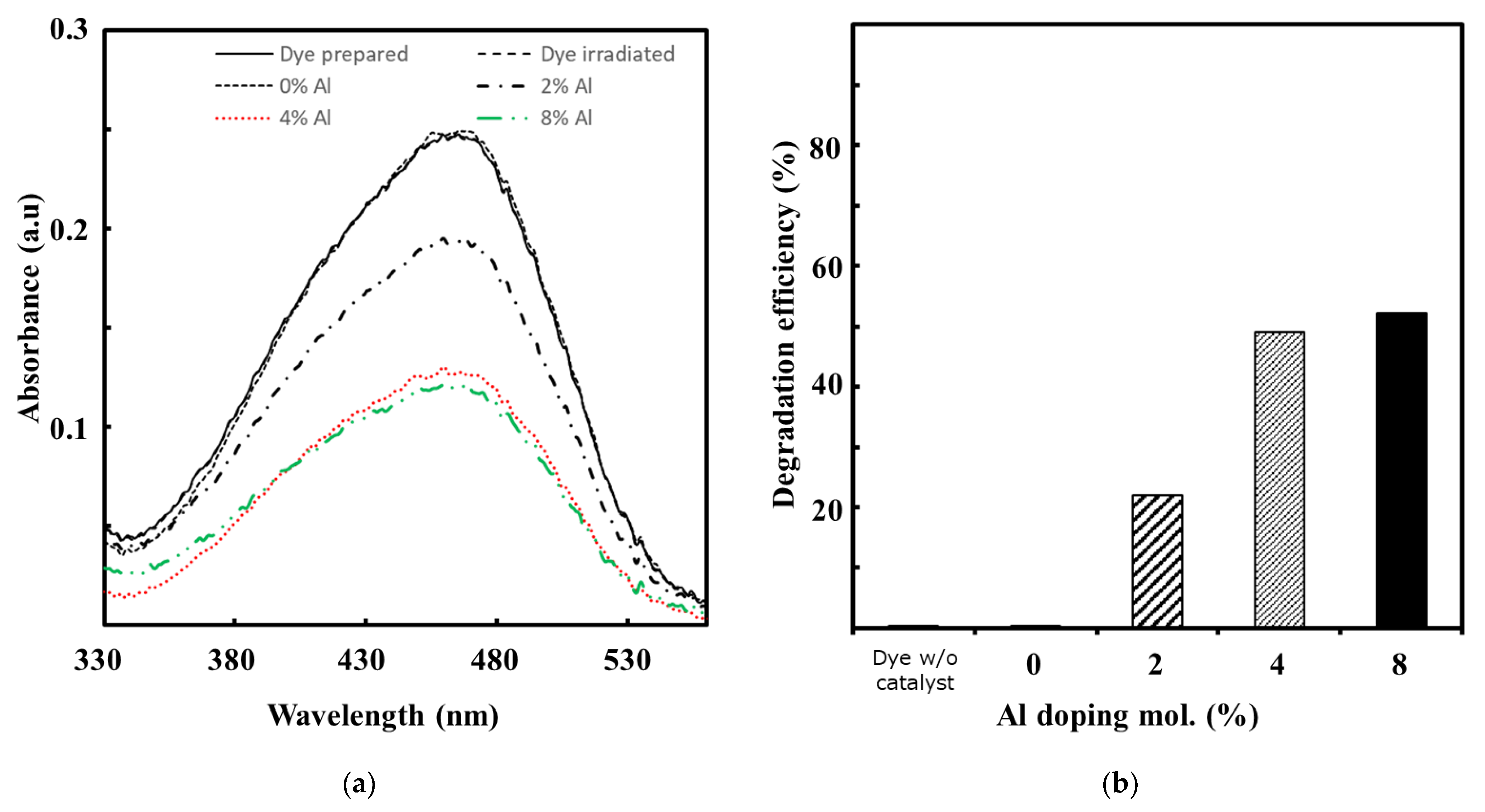

3.5. Photocatalytic Activities Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Stable and Clear Aqueous Solutions Containing Zinc and Aluminium Complexes

4.2. Fabrication of ZnO and Al-Doped ZnO via the Simple Aqueous Spray Method

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, H.; Zeng, Z.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, R.; Zhou, C.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, S. Recent Progress on Metal-Organic Frameworks Based- and Derived-Photocatalysts for Water Splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 383, 123196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, H. Zinc Oxide Nanostructured Thin Film as an Efficient Photoanode for Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation. Korean J. Mater. Res. 2020, 30, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, M.; Stroescu, H.; Mitrea, D.; Nicolescu, M. Various Applications of ZnO Thin Films Obtained by Chemical Routes in the Last Decade. Molecules 2023, 28, 4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johari, S.; Muhammad, N.Y.; Zakaria, M.R. Study of Zinc Oxide Thin Film Characteristics. EPJ Web Conf. 2017, 162, 01057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulis-Kapuscinska, A.; Kwoka, M.; Borysiewicz, M.A.; Wojciechowski, T.; Licciardello, N.; Sgarzi, M.; Cuniberti, G. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue at Nanostructured ZnO Thin Films. Nanotechnology 2023, 34, 155702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, J.S.; Song, J.B.; Kim, J.; Byun, D.; Son, C.S.; Yun, J.H.; Yoon, K.H. Efficiencies of CIGS Solar Cells Using Transparent Conducting Al-Doped ZnO Window Layers as a Function of Thickness. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2008, 53, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellam, M.; Azizi, S.; Bouras, D.; Fellah, M.; Obrosov, A. Degradation of Rhodamine B Dye under Visible and Solar Light on Zinc Oxide and Nickel-Doped Zinc Oxide Thin Films. Opt. Mater. 2024, 151, 115316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, A.E.; Montero-Muñoz, M.; López, L.L.; Ramos-Ibarra, J.E.; Coaquira, J.A.H.; Heinrichs, B.; Páez, C.A. Significantly Enhancement of Sunlight Photocatalytic Performance of ZnO by Doping with Transition Metal Oxides. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskabadi, M.R.; Rogé, V.; Bazargan, A.; Sargazi, H.; Barborini, E. An Introduction to Photocatalysis. In Photocatalytic Water and Wastewater Treatment; Bazargan, A., Ed.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2022; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Sukee, A.; Kantarak, E.; Singjai, P. Preparation of Aluminum Doped Zinc Oxide Thin Films on Glass Substrate by Sparking Process and Their Optical and Electrical Properties. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 901, 012153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, A.E.; Obibuzor, C.V.; Owoeye, V.A.; Ogunmola, E.D. Structural, Optical and Rectifying Properties of Spray Deposited Ni Doped and Undoped ZnO Thin Films. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. (IOSR-JHSS) 2021, 13, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Ma, J. Preparation and Characterization of (Al, Fe) Codoped Zno Films Prepared by Sol–Gel. Coatings 2021, 11, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Srivastava, A. Enhancement in NBE Emission and Optical Band Gap by Al Doping in Nanocrystalline ZnO Thin Films. Opto-Electron. Rev. 2018, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabortty, T.; Mina, S.; Habib, A.; Hussain, K.M.A.; Faruque, T.; Nahid, F. Fabrication and Characterization of Al Doped ZnO Thin Film Using Spin Coating Deposition System. IOSR J. Appl. Phys. (IOSR-JAP) 2018, 10, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouacheria, M.A.; Djelloul, A.; Adnane, M.; Larbah, Y.; Benharrat, L. Characterization of Pure and Al Doped ZnO Thin Films Prepared by Sol Gel Method for Solar Cell Applications. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2022, 32, 2737–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaab Khudhr, M.; Abass, K.H. Effect of Al-Doping on the Optical Properties of ZnO Thin Film Prepared by Thermal Evaporation Technique. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2016, 7, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.; Farhad, S.F.U.; Podder, J. Structural, Optical and Photocatalysis Properties of Sol–Gel Deposited Al-Doped ZnO Thin Films. Surf. Interfaces 2019, 16, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev, S.; Kekuda, D. Effect of Annealing Temperature on the Structural and Optical Properties of Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Thin Films Prepared by Spin Coating Process. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 73, 012149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazai, A.J.; Salman, E.A.; Jabbar, Z.A. Effect of Aluminum Doping on Zinc Oxide Thin Film Properties Synthesis by Spin Coating Method. Am. Sci. Res. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2016, 26, 202–211. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, M.; Ramos, R.; Martins, E.; Rangel, E.C.; Da Cruz, N.C.; Durrant, S.F.; Bortoleto, J.R.R. Al-Doping and Properties of AZO Thin Films Grown at Room Temperature: Sputtering Pressure Effect. Mater. Res. 2019, 22, e20180665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereu, R.A.; Mesaros, A.; Vasilescu, M.; Popa, M.; Gabor, M.S.; Ciontea, L.; Petrisor, T. Synthesis and Characterization of Undoped, Al and/or Ho Doped ZnO Thin Films. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 5535–5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.K.; Srivastava, A.; Srivastava, A.; Dubey, K.C. Growth of Transparent Conducting Nanocrystalline Al Doped ZnO Thin Films by Pulsed Laser Deposition. J. Cryst. Growth 2006, 294, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, H.; Durri, S.; Wibowo, S.; Hadiyanto, H.; Hidayanto, E. Rootlike Morphology of ZnO:Al Thin Film Deposited on Amorphous Glass Substrate by Sol-Gel Method. Phys. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 4749587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishimone, P.N.; Nagai, H.; Sato, M. Methods of Fabricating Thin Films for Energy Materials and Devices. In Lithium-Ion Batteries-Thin Film for Energy Materials and Devices; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, N.S.; Saraswat, S.K. Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting: An Ideal Technique for Pure Hydrogen Production. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2020, 97, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.Y. Synthesis of Ammonium Aluminum Oxalate from Bayer Aluminum Hydroxide. Mater. Lett. 2011, 65, 2621–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishimone, P.; Nagai, H.; Morita, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Sato, M. Highly-Conductive and Well-Adhered Cu Thin Film Fabricated on Quartz Glass by Heat Treatment of a Precursor Film Obtained Via Spray-Coating of an Aqueous Solution Involving Cu(II) Complexes. Coatings 2018, 8, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-mamun, R.; Iqbal, Z.; Rahim, A. Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Cu and Ni-Doped ZnO Nanostructures: A Comparative Study of Methyl Orange Dye Degradation in Aqueous Solution. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azfar, A.K.; Kasim, M.F.; Lokman, I.M.; Rafaie, H.A.; Mastuli, M.S. Comparative Study on Photocatalytic Activity of Transition Metals (Ag and Ni)Doped ZnO Nanomaterials Synthesized via Sol–Gel Method. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 191590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuselvi, C.; Arunkumar, A.; Rajaperumal, G. Growth and Characterization of Oxalic Acid Doped with Tryptophan Crystal for Antimicrobial Activity. Chem. Sin. 2016, 7, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Meshram, S.B.; Kushwaha, O.S.; Reddy, P.R.; Bhattacharjee, G.; Kumar, R. Investigation on the Effect of Oxalic Acid, Succinic Acid and Aspartic Acid on the Gas Hydrate Formation Kinetics. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 27, 2148–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, S.S.; Kirupavathy, S.S. An Insight on Spectral, Microstructural, Electrical and Mechanical Characterization of Ammonium Oxalate Monohydrate Crystals. Mater. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, M.; Belderbos, S.; Yañez-vilar, S.; Gsell, W.; Himmelreich, U.; Rivas, J. Development of Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles Coated with Polyacrylic Acid and Aluminum Hydroxide as an E Ffi Cient Contrast Agent for Multimodal Imaging. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1626. [Google Scholar]

- Pouran, H.M.; Banwart, S.A.; Romero-gonzalez, M. Applied Geochemistry Coating a Polystyrene Well-Plate Surface with Synthetic Hematite, Goethite and Aluminium Hydroxide for Cell Mineral Adhesion Studies in a Controlled Environment. Appl. Geochem. 2014, 42, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeep, K.M.; Bhat, S.; Dharmaprakash, S.M. Nonlinear Absorption Properties of ZnO and Al Doped ZnO Thin Films under Continuous and Pulsed Modes of Operations. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 102, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Majumdar, R.; Sen, A.; Maiti, H.S. Nanosized Bismuth Ferrite Powder Prepared through Sonochemical and Microemulsion Techniques. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 2100–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulama, A.A.; Mwabora, J.M.; Oduor, A.O.; Muiva, C.C. Optical Properties and Raman Studies of Amorphous Se-Bi Thin Films. African Rev. Phys. 2014, 9, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, S.; Saroja, M.; Venkatachalam, M.; Parthasarathy, G. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using ZnO Thin Films. Int. J. Chem. Concepts 2017, 03, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Jellal, I.; Daoudi, O.; Nouneh, K.; Boutamart, M. Comparative Study on the Properties of Al- and Ni-Doped ZnO Nanostructured Thin Films Grown by SILAR Technique: Application to Solar Photocatalysis. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2023, 55, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, H.; Sato, M. Heat Treatment in Molecular Precursor Method for Fabricating Metal Oxide Thin Films. In Heat Treatment—Conventional and Novel Applications; InTechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2012; Volume 100C, pp. 147–167. ISBN 9789583213208. [Google Scholar]

- Thein, M.T.; Pung, S.Y.; Aziz, A.; Itoh, M. The Role of Ammonia Hydroxide in the Formation of ZnO Hexagonal Nanodisks Using Sol–Gel Technique and Their Photocatalytic Study. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2015, 10, 1068–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.T.; Tu, N.H.; Le, H.H.; Ryu, K.Y.; Le, K.B.; Pillai, K.; Yi, J. Improving the Ethanol Sensing of ZnO Nano-Particle Thin Films—The Correlation between the Grain Size and the Sensing Mechanism. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2011, 152, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | FWHM | D (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| ZnO | 0.3300 | 26 |

| 2% Al-ZnO | 0.4284 | 20 |

| 4% Al-ZnO | 0.9595 | 8 |

| 8% Al-ZnO | - | - |

| Photocatalyst | Method of Fabrication | Dye | Experimental Conditions (Light, Time, Dye Conc.) | %D | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO | SILAR | Orange G | Visible light, 3 h, 10–5 M | 14.4 | [38] |

| 2% Al-ZnO | 44.6 | ||||

| 4% Al-ZnO | 44.1 | ||||

| 8% Al-ZnO | 46.1 | ||||

| ZnO | Spray-coating | Methyl Orange | Visible light, 4 h, 0.76 × 10–6 M | 0.26 | Current work |

| 2% Al-ZnO | 22 | ||||

| 4% Al-ZnO | 49 | ||||

| 8% Al-ZnO | 52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Titus, W.N.; Uusiku, A.; Hishimone, P.N. Aluminium-Doped Zinc Oxide Thin Films Fabricated by the Aqueous Spray Method and Their Photocatalytic Activities. Coatings 2026, 16, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010020

Titus WN, Uusiku A, Hishimone PN. Aluminium-Doped Zinc Oxide Thin Films Fabricated by the Aqueous Spray Method and Their Photocatalytic Activities. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleTitus, Wilka N., Alina Uusiku, and Philipus N. Hishimone. 2026. "Aluminium-Doped Zinc Oxide Thin Films Fabricated by the Aqueous Spray Method and Their Photocatalytic Activities" Coatings 16, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010020

APA StyleTitus, W. N., Uusiku, A., & Hishimone, P. N. (2026). Aluminium-Doped Zinc Oxide Thin Films Fabricated by the Aqueous Spray Method and Their Photocatalytic Activities. Coatings, 16(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010020