The Origin of KO-KUTANI Porcelain—Part II: The Unearthed Secrets of the Hakuji Shallow Bowl

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

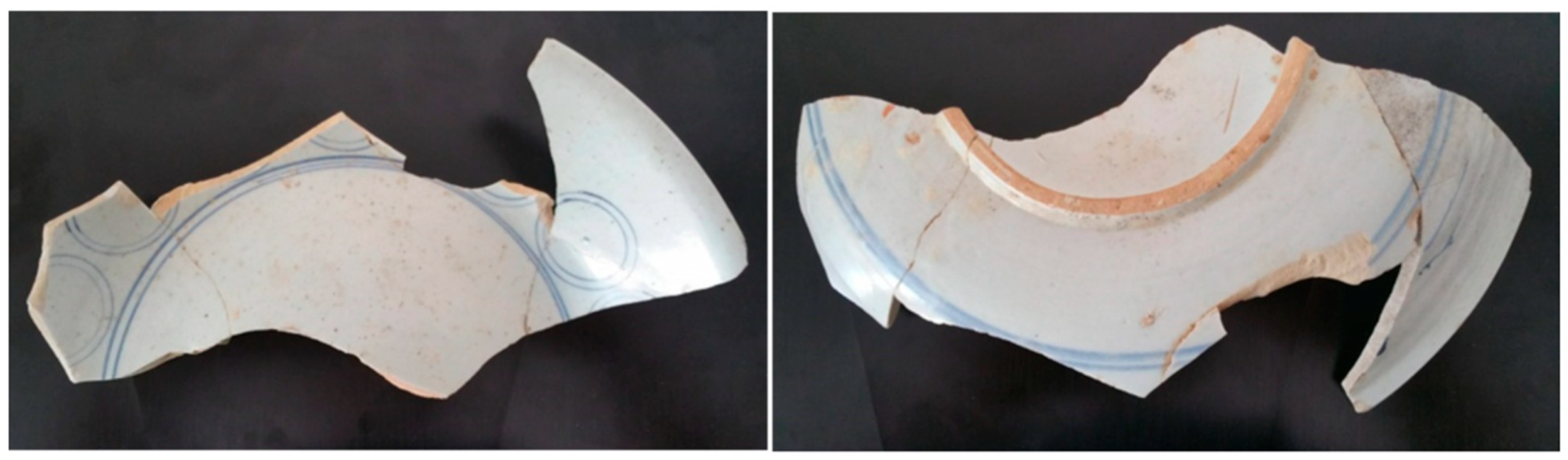

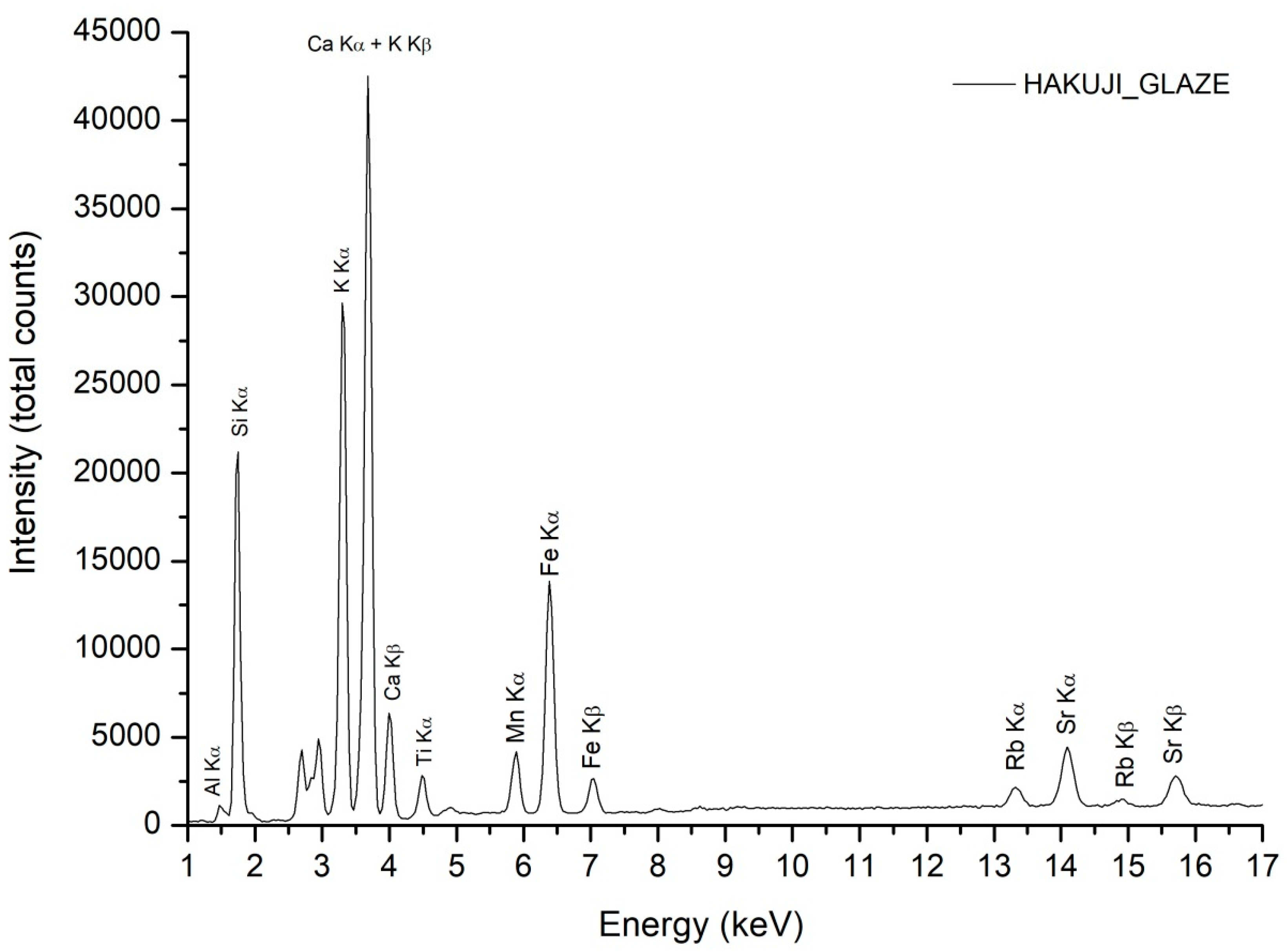

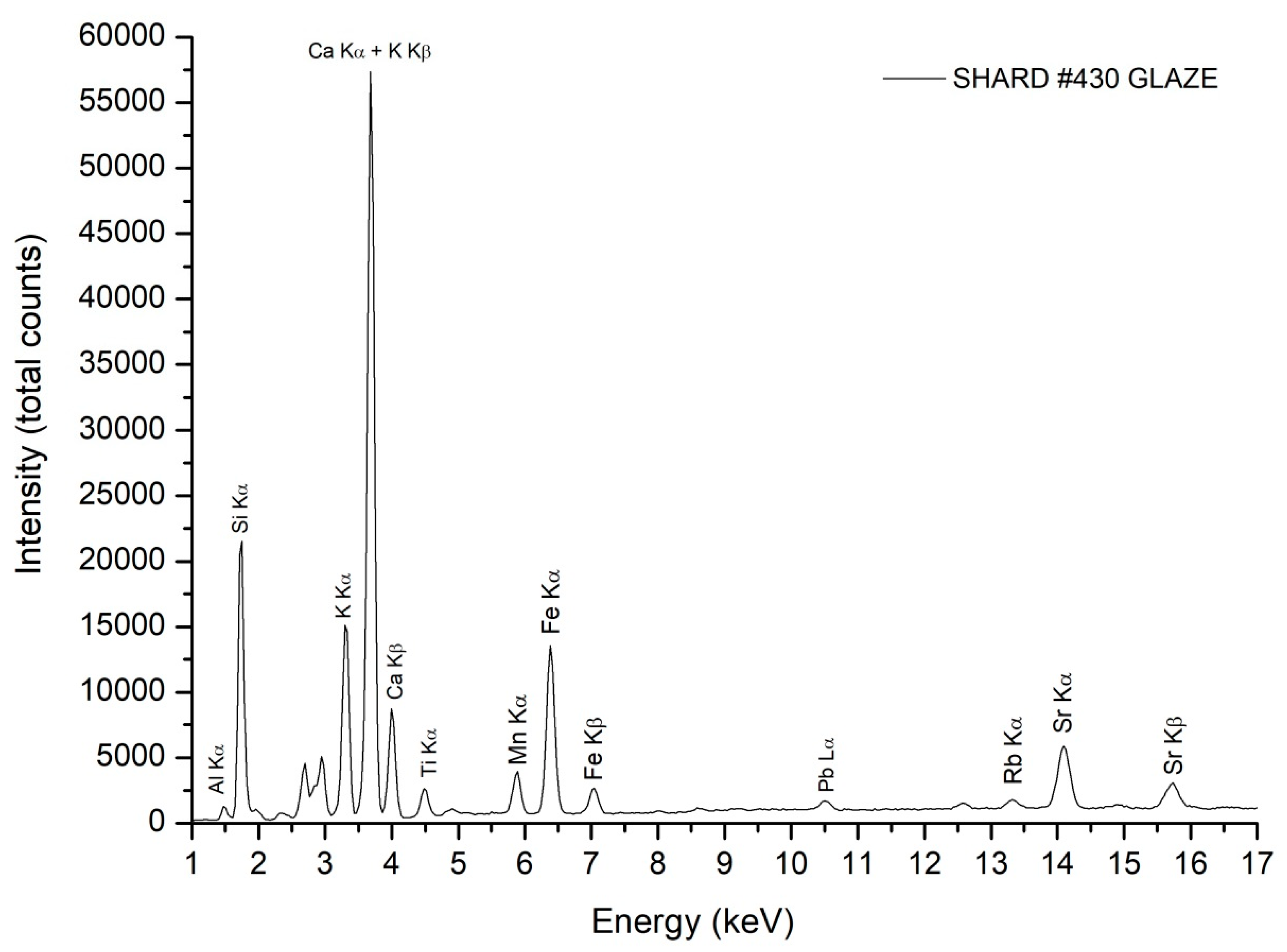

2.1. Analyzed Porcelains and Excavated Hakuji Bowl

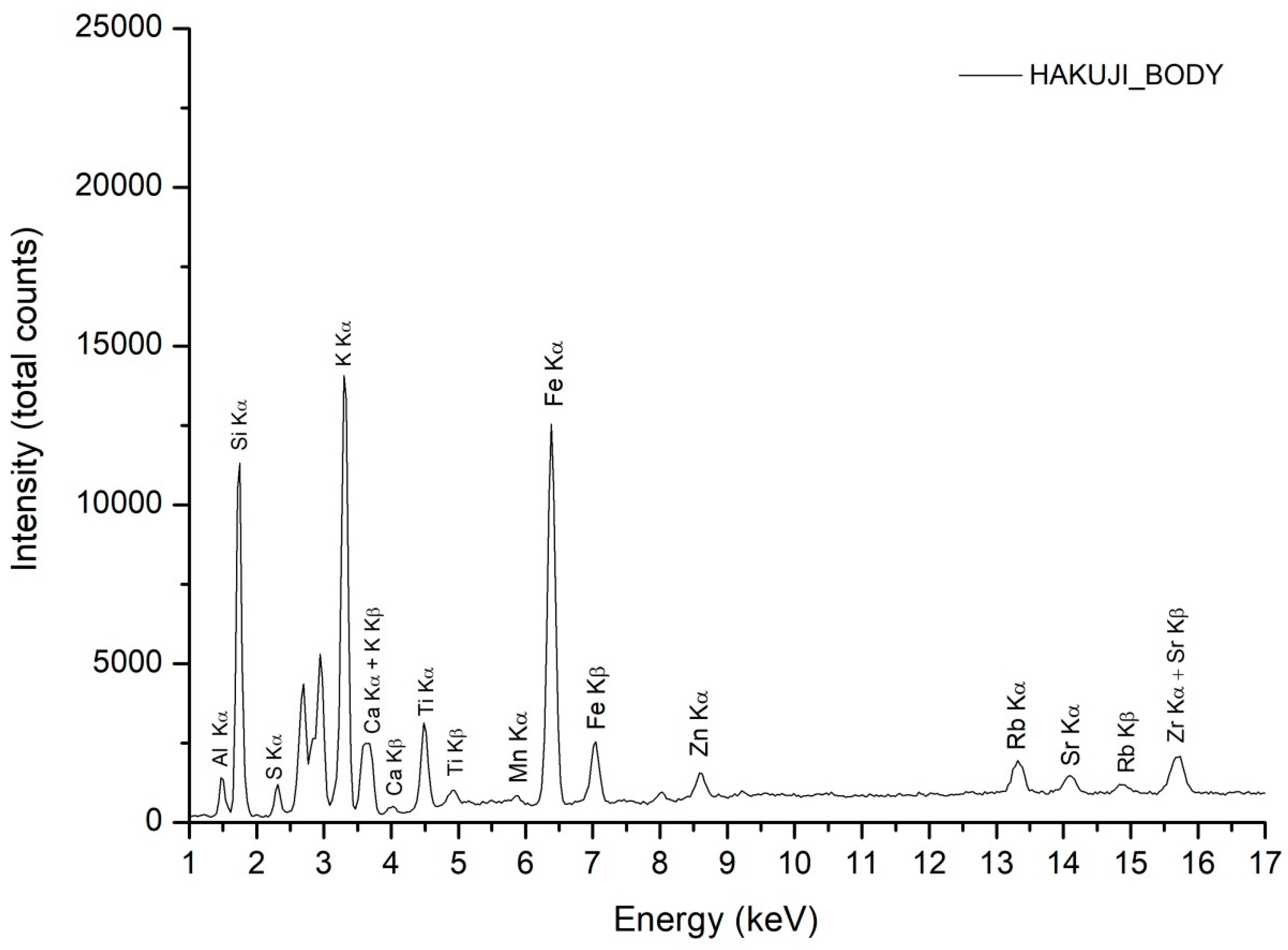

2.2. XRF Spectrometer: Experimental and Measurement Parameters

3. Results and Discussion

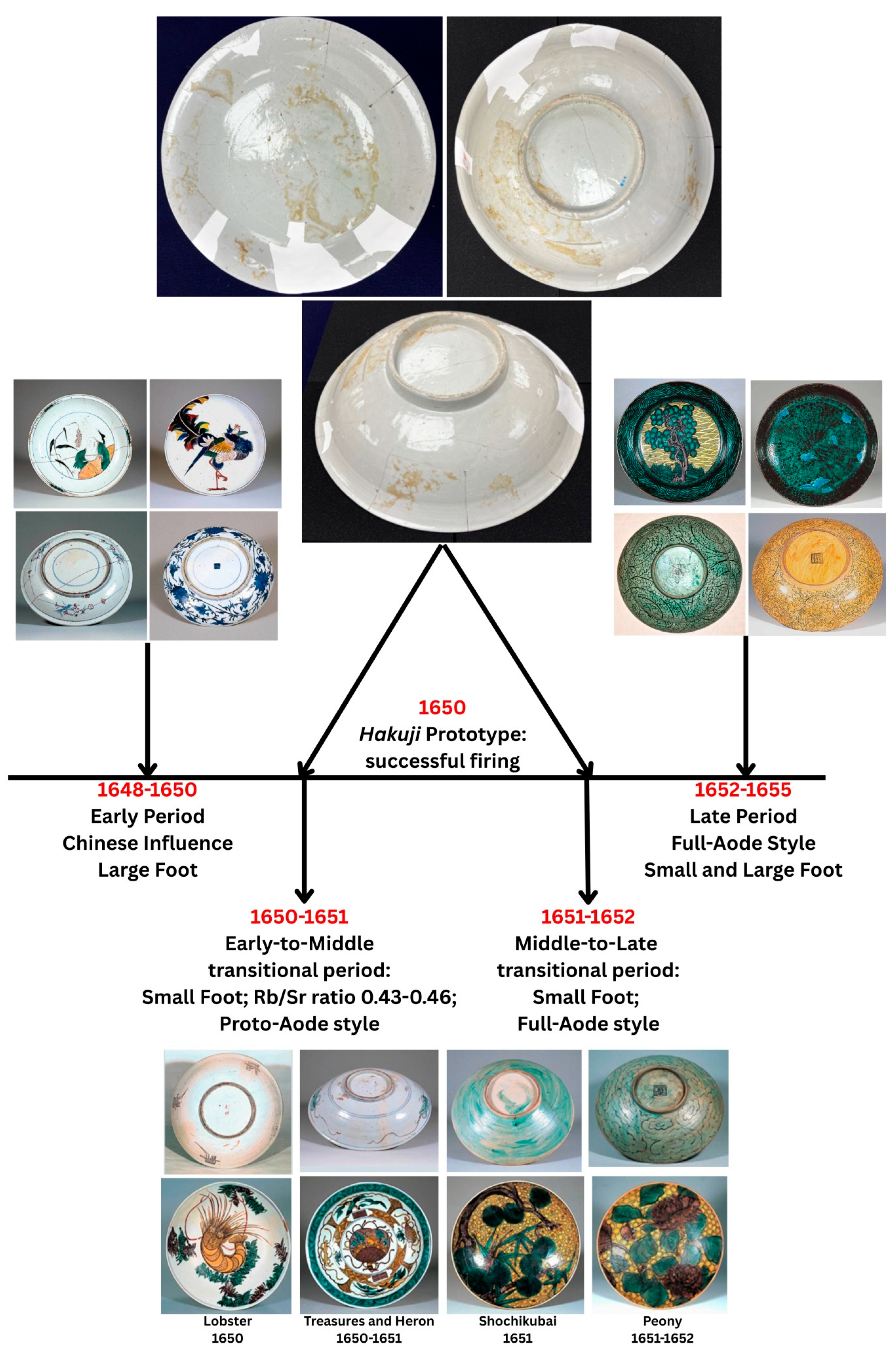

The Hakuji Shallow Bowl and the Massive Body of Ko-Kutani Enameled Wares: Origin of Potting Style in Kaga

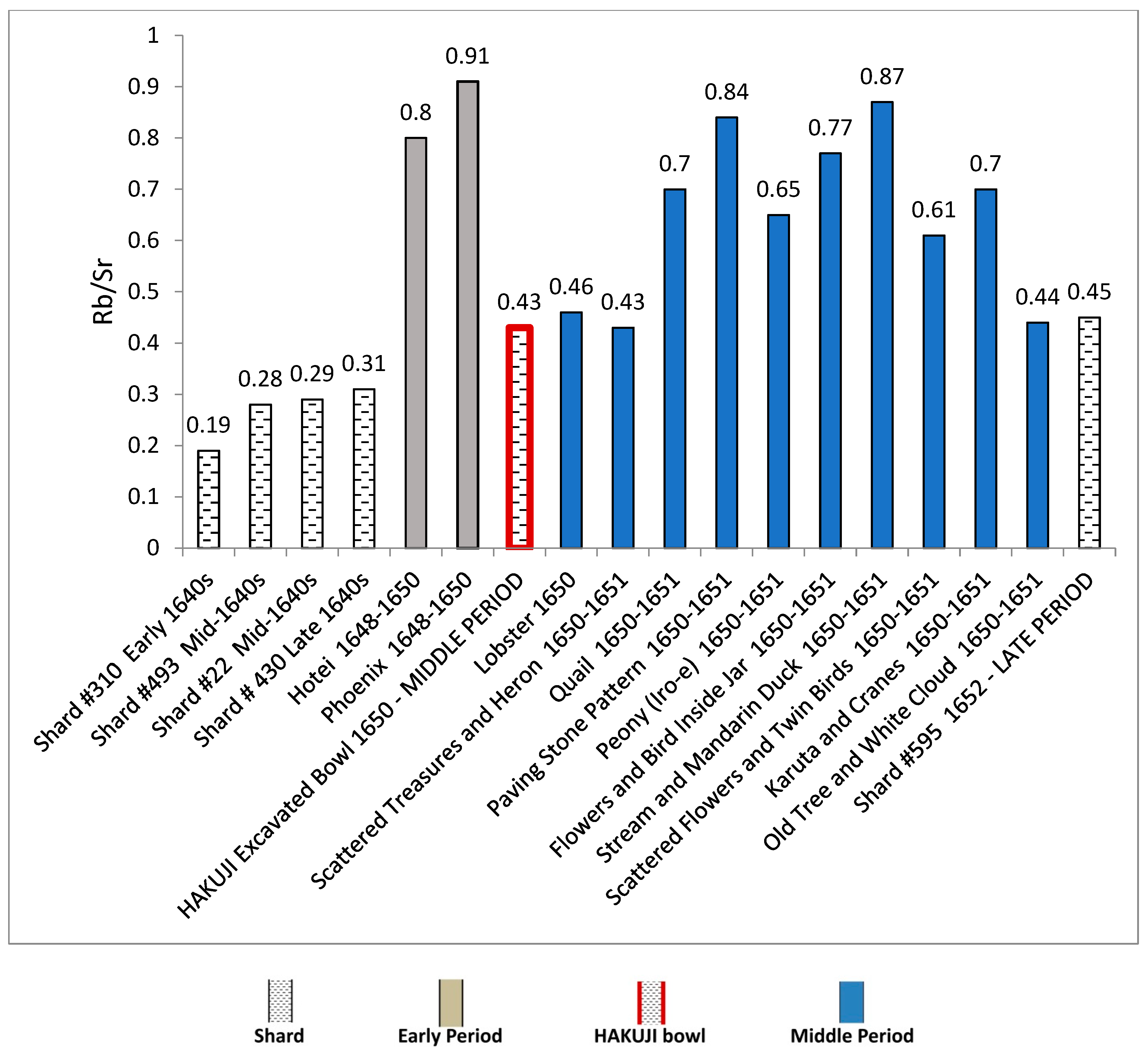

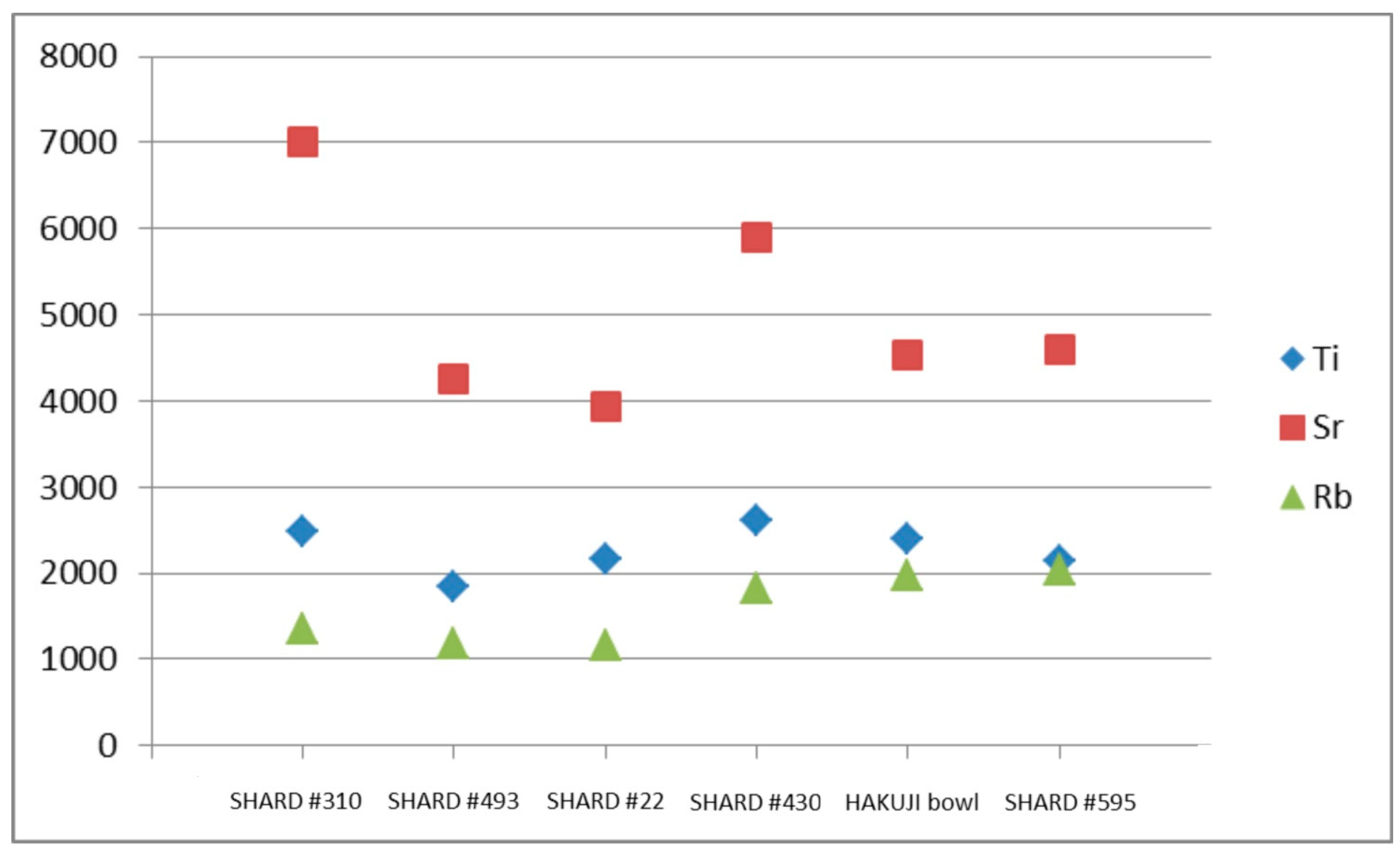

4. The Hakuji Bowl and Excavated Shards: Rb/Sr Ratios and Preliminary Considerations on Glazes

5. PRE-HAKUJI PHASE: Initial Experimentation with Glazes in the 1640s

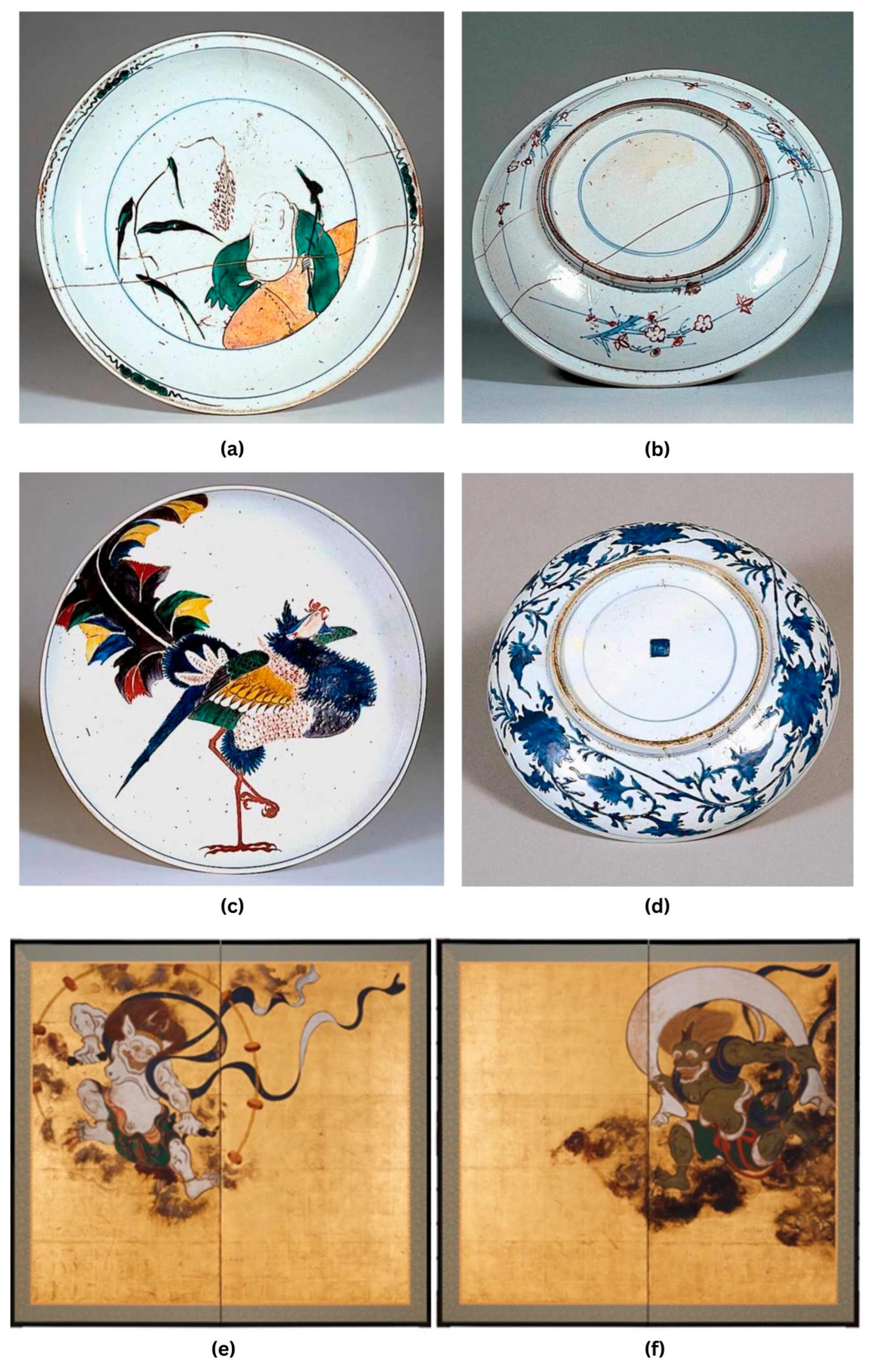

PRE-HAKUJI PHASE: The Early Period (1648–1650)

6. Hakuji Prototype Development in 1650: Implications on Ko-Kutani Production

7. Post-Hakuji Phase: The Middle Period (1650–1651)

7.1. Post-Hakuji Phase: Ko-Kutani Glazes in the Middle Period (1650–1651)

7.2. Post-Hakuji Phase: The Late Period (1651–1655)

7.3. Post-Hakuji Phase: Body Recipe for the New Decoration Styles

7.4. Post-Hakuji Phase: Body Recipe for the New Decoration Styles—Additional Remarks

8. Hakuji Shallow Bowl—Overall Influence on Ko-Kutani Production—Further Remarks

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montanari, R.; Murase, H.; Alberghina, M.F.; Schiavone, S.; Pelosi, C. The Origin of Ko-Kutani Porcelain: New Discoveries and a Reassessment. Coatings 2024, 14, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHK Publishing Inc. NHK 歴史ドキュメント6 (NHK Historical Documents 6); NHKPublishing Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 1987; pp. 18–54. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, R.; Alberghina, M.F.; Schiavone, S.; Pelosi, C. The Jesuit painting Seminario in Japan: European Renaissance technology and its influence on Far Eastern Art. X-Ray Spect. 2022, 51, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, R. The Art of the Jesuit Mission in 16th-Century Japan: The Italian Painter Giovanni Cola and the Technological Transfer at the Painting Seminario in Arie. Eikón Imago 2022, 11, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa Prefecture Board of Education. Kutani Old Kiln Excavation Report; Ishikawa Prefecture Board of Education: Kanazawa, Japan, 2007. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa Prefecture Board of Education; Ishikawa Prefecture Archaeological Foundation. Kaga City Kutani Kiln-Site AII Excavation Report; Ishikawa Prefecture Board of Education; Ishikawa Prefecture Archaeological Foundation: Kanazawa, Japan, 2006. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, H. Japanese Export Porcelain During the 17th and 18th Century. Ph.D. Thesis, Oxford University, Oxford, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, R.; Nobuyuki, M.; De Bonis, A.; Colomban, P.; Alberghina, M.F.; Grifa, C.; Izzo, F.; Morra, V.; Pelosi, C.; Schiavone, S. The early porcelain kilns of Arita: Identification of raw materials and their use from the 17th to the 19th century. Open Ceram. 2022, 9, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyongshin Koh Choo, C.; Kil Choo, W.; Ahn, S.; Eun Lee, Y.; Ho Kim, G.; Sook Lee, Y. A study of the chemical composition of Korean traditional ceramics (III): Comparison of punch’ŏng with Koryŏ ware and chosŏn whiteware. J. Conserv. Sci. 2011, 27, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Impey, O. The Early Porcelain Kilns of Japan; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, N. Excavated Ceramics, Exhibition Guidebook; Arita History and Folklore Museum: Arita, Japan, 2021. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, N. The Origin of Imari Porcelain—Excavated Shards from Komizo Kiln; Sojusha Art Publishing: Kyoto, Japan, 2020. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Arita City Board of Education. Yanbeta Kiln Excavation Report; Arita City Board of Education: Arita, Japan, 2015. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Arita City Board of Education. Excavation at the Workshop Related to the Yanbeta Kiln Site, A Nationally Designated Historic Site; Arita City Board of Education: Arita, Japan, 2017. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Henderson, J.; Evans, J. A new method of identifying the flux in ancient Chinese high fired glaze—Sr Isotopic composition analysis. In Recent Advances in the Scientific Research on Ancient Glass and Glaze (Series on Archaeology and History of Science in China); Li, Q., Henderson, J., Gan, F., Eds.; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 353–373. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, T. On the Chemical Constituents of the Heart Wood of Distylium Racemosum S. et Z. J. Fac. Agric. Kyushu Univ. 1951, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fitski, M. Kakiemon Porcelain—Handbook; Leiden University Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Murase, H. 総合知の観点から古九谷を捉え直す(Rethinking Ko-Kutani from the perspective of Convergence Knowledge). In 石川県九谷焼美術館紀要『九谷を拓く』 (第7号) (Bulletin of the Kutaniyaki Art Museum, “Pioneering Kutani” (Kutani wo Hiraku); 2025; Volume 7, pp. 5–35, (In Japanese and English); Available online: https://researchmap.jp/alleukeinen/published_papers/50460974?lang=en (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Montanari, R.; Murakami, N.; Colomban, P.; Alberghina, M.F.; Pelosi, C.; Schiavone, S. European ceramic technology in the Far East: Enamels and pigments in Japanese art from the 16th to the 20th century and their reverse influence on China. Herit. Sci. 2020, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analyzed Porcelains | Historical Period | XRF Results: Enamel Matrix, Chromophores and Glazes | Identified Pigments | |

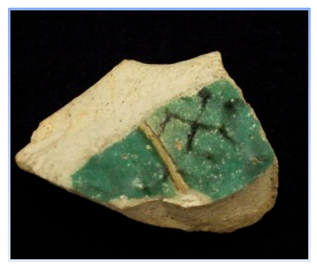

| Shard #310 | Early 1640s | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, Si (Ca, Fe, K, Zn, Ni, Ti, Al) | Cu-Zn Green |

| Main Characteristics: Earliest Ko-Kutani enameled porcelain. Arita-based transparent glaze with Rb/Sr ratio of 0.19. | ||||

| Shard #493 | Mid-1640s | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, Si, K (Fe, Ca, Zn, Ti, Mn, Ni, Al) | Cu-Zn Green |

| Main Characteristics: Earliest Ko-Kutani enameled porcelain. Arita-based transparent glaze with Rb/Sr ratio of 0.28. | ||||

| Shard #22 | Mid-1640s | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K, Si (Fe, Ca, Zn, Ni, Mn, Ti, Al) | Cu-Zn Green |

| Main Characteristics: Earliest Ko-Kutani enameled porcelain. Arita-based transparent glaze with Rb/Sr ratio of 0.29. | ||||

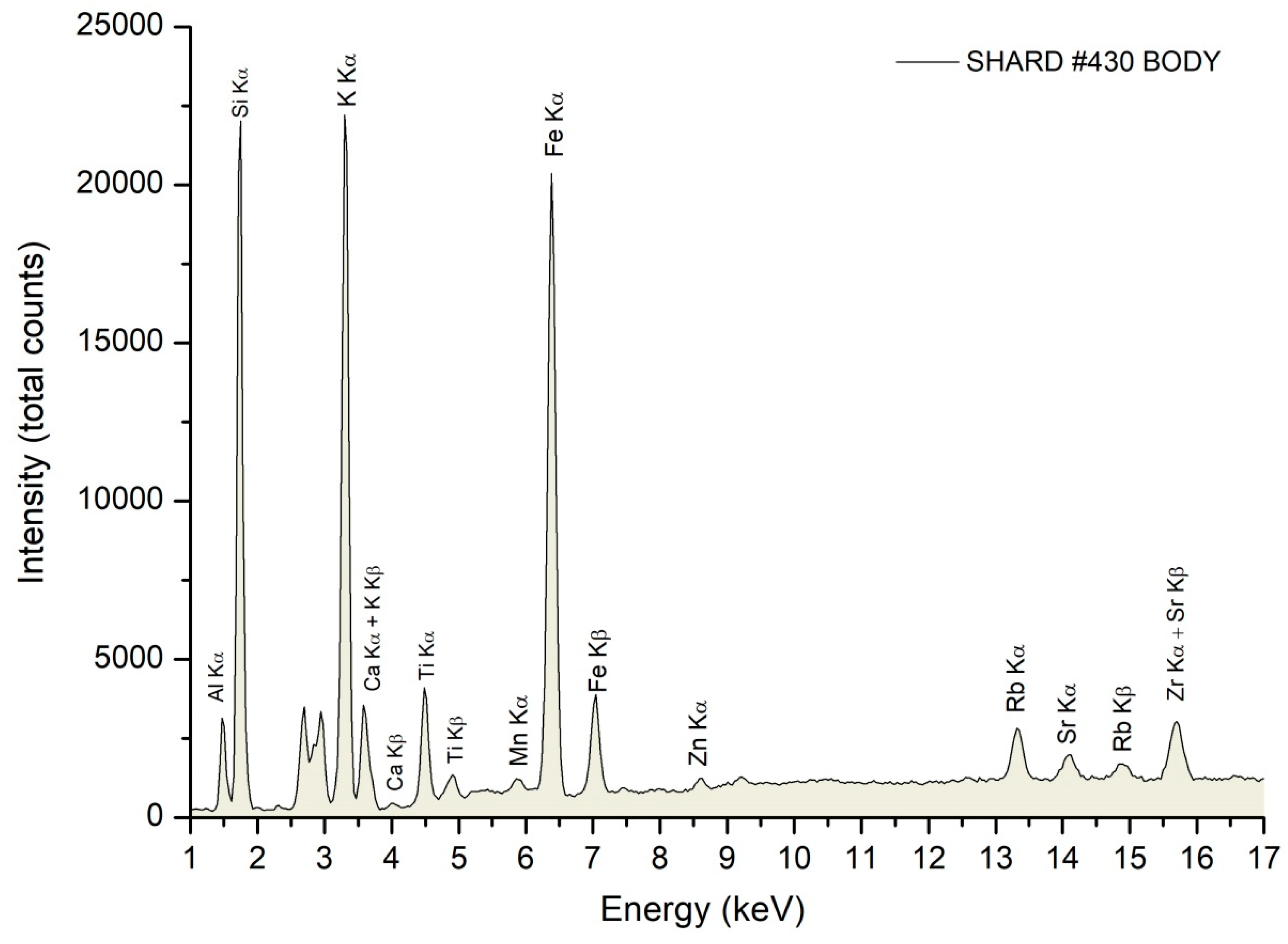

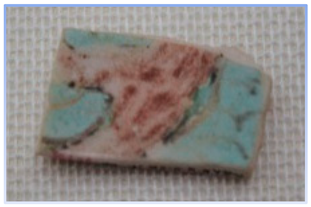

| Shard #430 | Late 1640s | Glaze Ca, Si, K, Fe, Sr (Mn, Ti, Rb, Al, Pb) Red Enamel Ca, Fe, Si, Pb, K (Sr, Mn, Ti, Rb, Al) | Fe-based Red |

| Main Characteristics: Earliest Ko-Kutani enameled porcelain. Arita-based transparent glaze with Rb/Sr ratio of 0.31. | ||||

| Hotei | Early Period (1648–1650) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K, Si (Fe, Ca, Zn, As, Ni, Mn, Ti, Ca) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Early Period enameled body type with large foot. Kaga-incepted decoration style based on Tawaraya Sotatsu’s painting composition. Kaga opaque glaze with Rb/Sr ratio of 0.8. | ||||

| Phoenix | Early Period (1648–1650) | Blue Enamel Pb, K, Si (Cu, Fe, Co, Ni, As, Ti, Ca) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K, Si (Fe, Ca, Zn, As, Ni, Mn, Ti) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Early Period enameled body type with large foot. Decoration style with its inception in Kaga based on Tawaraya Sotatsu’s painting composition. Kaga opaque glaze with Rb/Sr ratio of 0.91. Notable Features: - Introduction of Smalt-based overglaze-blue enamel. - Underside fully enameled with Smalt-based blue. | ||||

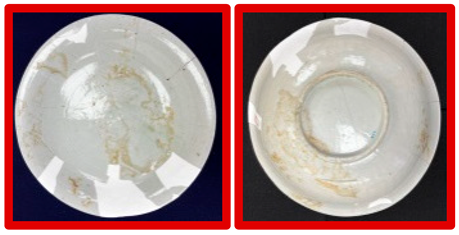

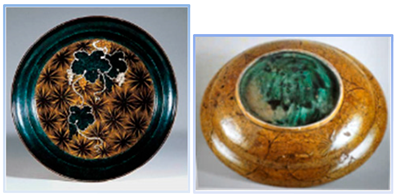

| HAKUJI bowl (#12-9) | Middle Period (1650) | Glaze Ca, K, Si, Fe, Sr (Mn, Ti, Rb, Al) Body K, Fe, Si (Ti, Ca, Rb, Al, Zn, Cu) | – |

| Newly Introduced Body Prototype: - Shallow bowl with Korean-based small foot. - Introduction of the new Hakuji glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.40. | ||||

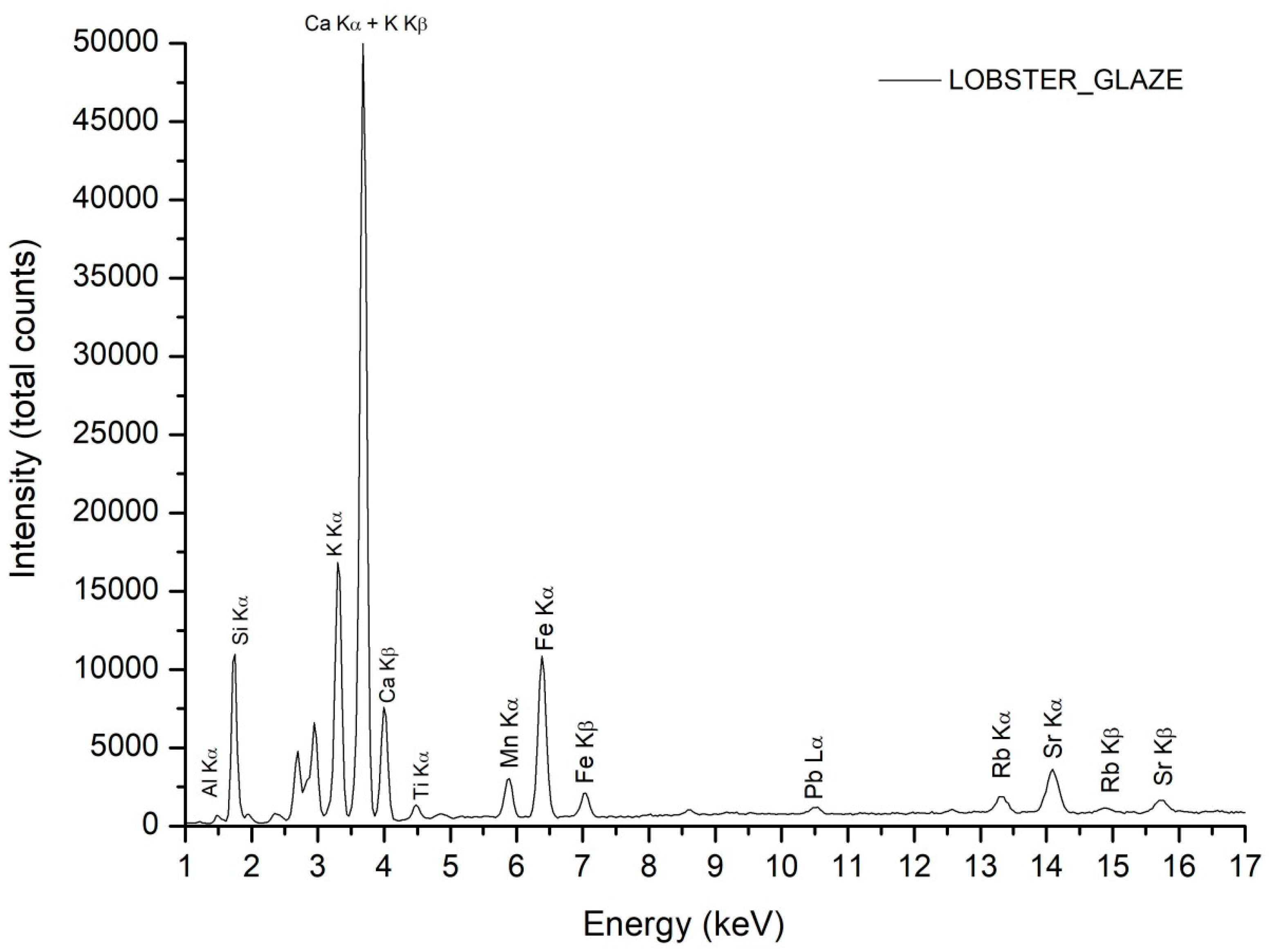

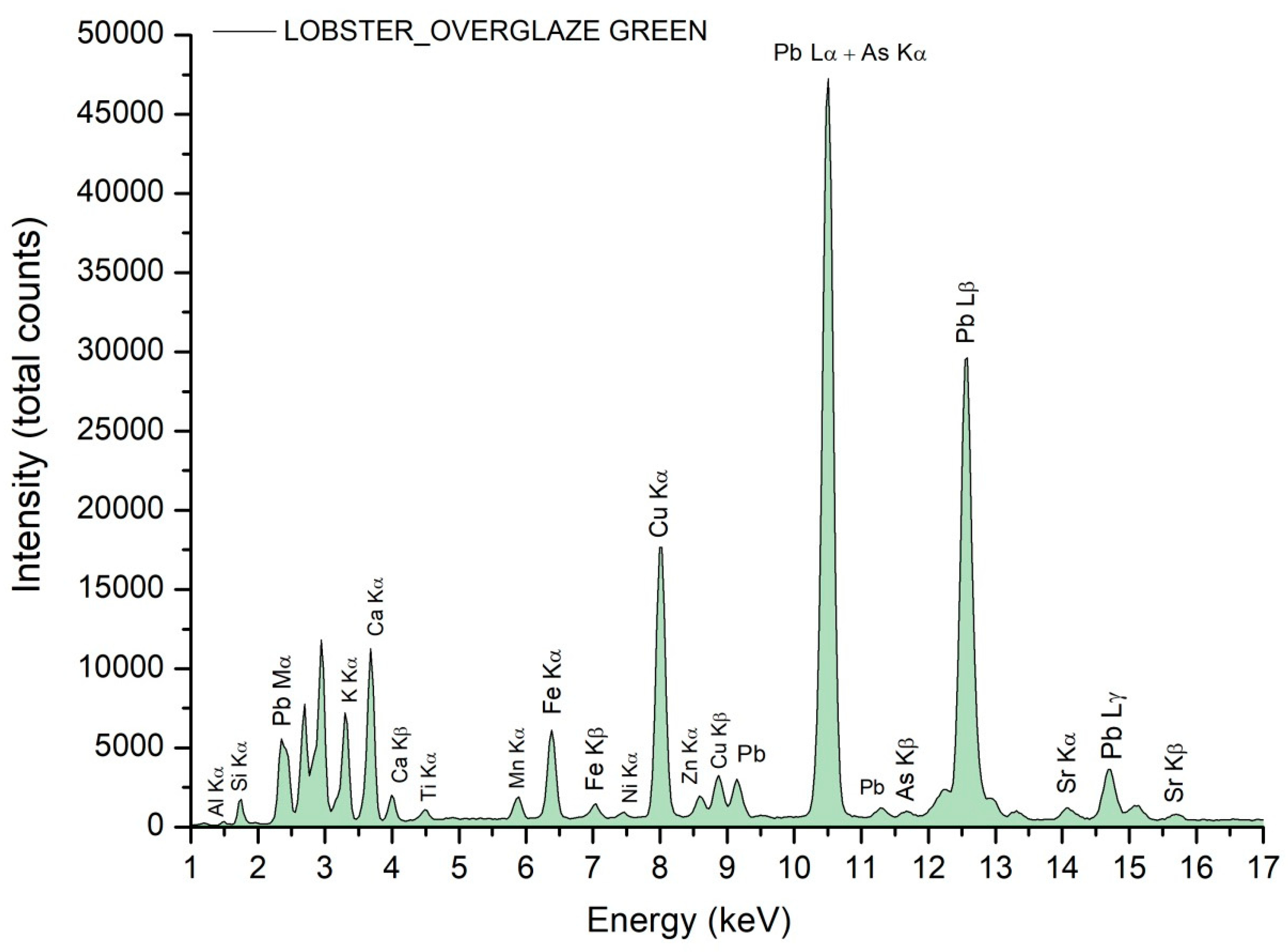

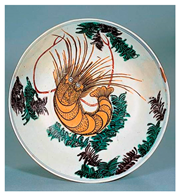

| Lobster | Middle Period (1650) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, Ca, K, Fe (Si, Mn, Zn, Ti, As, Ni) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Transitional piece (Early-to-Middle Period): - Hakuji-type body with small foot. - Decoration style with its inception in Kaga based on Tawaraya Sotatsu’s painting composition. - New Hakuji glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.46. | ||||

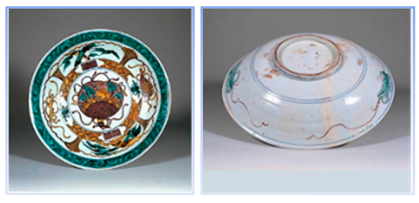

| Scattered Treasures and Heron | Middle Period (1650) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K, Si (Fe, Ca, Zn, As, Ni, Ti, Ca) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Transitional piece (Early-to-Middle Period): - Hakuji-type body with small foot. - Initial form of Proto-Aode decoration style. - New Hakuji glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.43. - Stabilization and standardization of production. | ||||

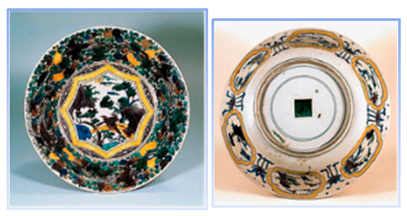

| Quail | Middle Period (1651) | Blue Enamel Pb, K, Si (Cu, Fe, Co, Ni, As, Ti, Ca) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K, Si (Fe, Zn, As, Ni, Mn, Ti, Ca) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Shallow bowl with large foot, decorated in Proto-Aode style. Transitional features: - Return to initial Kaga opaque glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.70. - Introduction of large foot in Proto-Aode decoration style after production stabilization and standardization. - Introduction of Smalt-based overglaze-blue in the Middle Period. | ||||

| Paving Stone Pattern | Middle Period (1651) | Blue Enamel Pb, K (Cu, Fe, Co, Ni, As, Si, Zn, Ti, Al, Ca) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Fe, Zn, As, Ni, Mn, Ti, Si, Ca) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with large foot, decorated in Proto-Aode style. Kaga opaque glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.84. | ||||

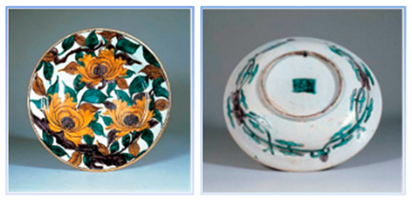

| Peony (Iro-e) (Iro-e Botan) | Middle Period (1651) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Fe, Zn, As, Ni, Mn, Ti, Si) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with large foot, decorated in Proto-Aode style. Kaga opaque glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.65. | ||||

| Flowers and Birds Inside Jar | Middle Period (1651) | Blue Enamel Pb, K (Cu, Fe, Co, Ni, As, Si, Zn, Ti, Ca) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Fe, Zn, As, Ni, Mn, Ti, Si, Ca) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with large foot, decorated in Proto-Aode style. Kaga opaque glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.77. | ||||

| Stream and Mandarin Duck | Middle Period (1651) | Blue Enamel Pb, K (Cu, Fe, Co, Ni, As, Zn, Si, Ti, Ca) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Si, Fe, Zn, As, Ni, Ti, Mn, Ca) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with large foot, decorated in Proto-Aode style. Kaga opaque glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.87. | ||||

| Scattered Flowers and Twin Birds | Middle Period (1651) | Blue Enamel Pb, K (Si, Cu, Fe, Co, Ni, As, Ti, Zn, Ca) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Fe, Si, Zn, As, Ni, Mn, Ti, Ca) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with large foot, decorated in Proto-Aode style. Kaga opaque glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.61. | ||||

| Karuta and Cranes | Middle Period (1651) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Si, Fe, Zn, As, Ni, Mn, Ti, Ca) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with Hakuji-type body and small foot, decorated in Proto-Aode style. Kaga opaque glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.70. | ||||

| Old Tree and White Cloud | Middle Period (1651) | Blue Enamel Pb, K, Fe **, Cu (Zn **, Mn **, Co, Ni, As, Ti, Si, Ca, Al) ** from black decoration layer Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Fe, Zn, As, Si, Ni, Ti, Si) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Transitional piece (Middle-to-Late Period): - Shallow bowl with large foot decorated in Proto-Aode style. - Return to Hakuji glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.44. - Introduction of green washed underside. | ||||

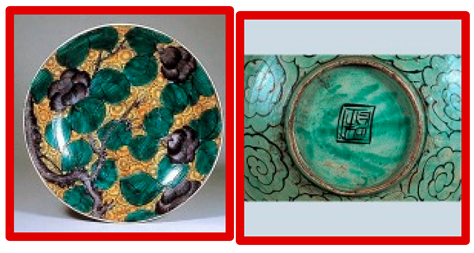

| Shochikubai | Late Period (1651) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Fe, Zn, As, Ti, Ni, Si) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Transitional piece (Middle-to-Late Period): - Shallow bowl with Hakuji-type body and small foot. - Unwashed base. - Decorated in initial form of Full-Aode style. | ||||

| Peony | Late Period (1651–1652) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, Zn, K (Fe, As, Mn, Si, Ti, Ni, Ca) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with Hakuji-type body and small foot, decorated in Full-Aode style. Notable feature: Introduction of the iconic snowflake design on the underside. | ||||

| Aged Pine Tree | Late Period (1651–1652) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K, Zn (As, Fe, Si, Mn, Ni, Ti, Ca) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with Hakuji-type body and small foot, decorated in Full-Aode style. Snowflake design on the underside. | ||||

| Bamboo Leaves | Late Period (1651–1652) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, Zn, K (Si, As, Fe, Ca, Ti) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with Hakuji-type body and small foot, decorated in Full-Aode style. Snowflake design on the underside. | ||||

| Camellias | Late Period (1651–1652) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K, Si (Fe, Zn, Ca, Ni, Ti, Mn, As, Al) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with Hakuji-type body and small foot, decorated in Full-Aode style. Snowflake design on the underside. | ||||

| Shard #595 | Late Period (1652) | Blue Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Si, Fe, Co, Ni, As, Zn, Mn, Ti, Al, Ca) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K, Si (Fe, Ca, Zn, Ni, Ti, Mn, Al) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn Green |

| Transitional piece (Middle-to-Late Period): - Enameled porcelain with Hakuji-type glaze: Rb/Sr = 0.45. - Experimentation with Smalt-based overglaze-blue enamel. | ||||

| Poppy | Late Period (1652) | Blue Enamel Pb, K, Fe (Si, Co, Ni, As, Ca, Ti) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Ca, Si, Fe, Zn, Ni, Mn, Ti) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with Hakuji-type body and small foot, decorated in Full-Aode style. Notable features: - Introduction of systematic Smalt-based overglaze-blue enamel decoration in the Late Period. | ||||

| Pine Tree and Peacock | Late Period (1652) | Blue Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Si, Fe, Co, Ni, As, Zn, Ti, Ca) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Si, Fe, Zn, Ni, Ti, Mn, Ca) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with large foot in Full-Aode style. Notable features: Introduction of large foot with fully washed base in the Late Period. | ||||

| Chestnuts and Waves | Late Period (1652) | Blue Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Si, Fe, Co, Ni, As, Zn, Ti, Ca) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Si, Fe, Zn, Ni, Ti, Mn, Ca) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with large foot in Full-Aode style. Notable features: Introduction of floral scroll design on the underside to replace the iconic snowflake design. | ||||

| Bamboo and Chrysanthemum | Late Period (1652–1653) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Fe, Ca, Si, As, Zn, Ti, Ni, Al, Mn) | Cu-Zn-As Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with large foot in Full-Aode style. Notbale features: - Introduction of yellow-washed underside on large-footed bowls. - Unwashed base. | ||||

| Scattered Cherry Blossoms | Late Period (1652–1653) | Blue Enamel Pb, K, Cu (Si, Fe, Co, Ni, As, Zn, Ti, Ca, Al, Mn) Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Si, Fe, Zn, Ni, Ti, Ca) | Smalt Blue Cu-Zn Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with large foot decorated in Full-Aode style. Notable features: Introduction of yellow wash to cover both underside and base. | ||||

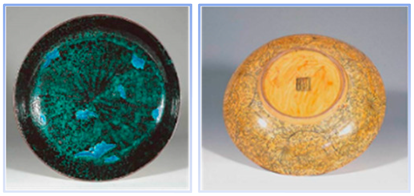

| Grapevine | Late Period (1653–1654) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Fe, Zn, Si, Ti, Ni, Ca) | Cu-Zn Green |

| Main Characteristics: Shallow bowl with large foot in Full-Aode style. Notable features: Underside bearing two different washes, brown and green. | ||||

| Jumokuzu (Big Tree) | Late Period (1654–1655) | Green Enamel Pb, Cu, K (Si, Fe, Zn, Ni, Ti, Ca) | Cu-Zn Green |

| Main Characteristics: Hakuji-type body with small foot in Full-Aode style. Notable features: Latest example of small-foot recurrence before Ko-Kutani kiln shut down. | ||||

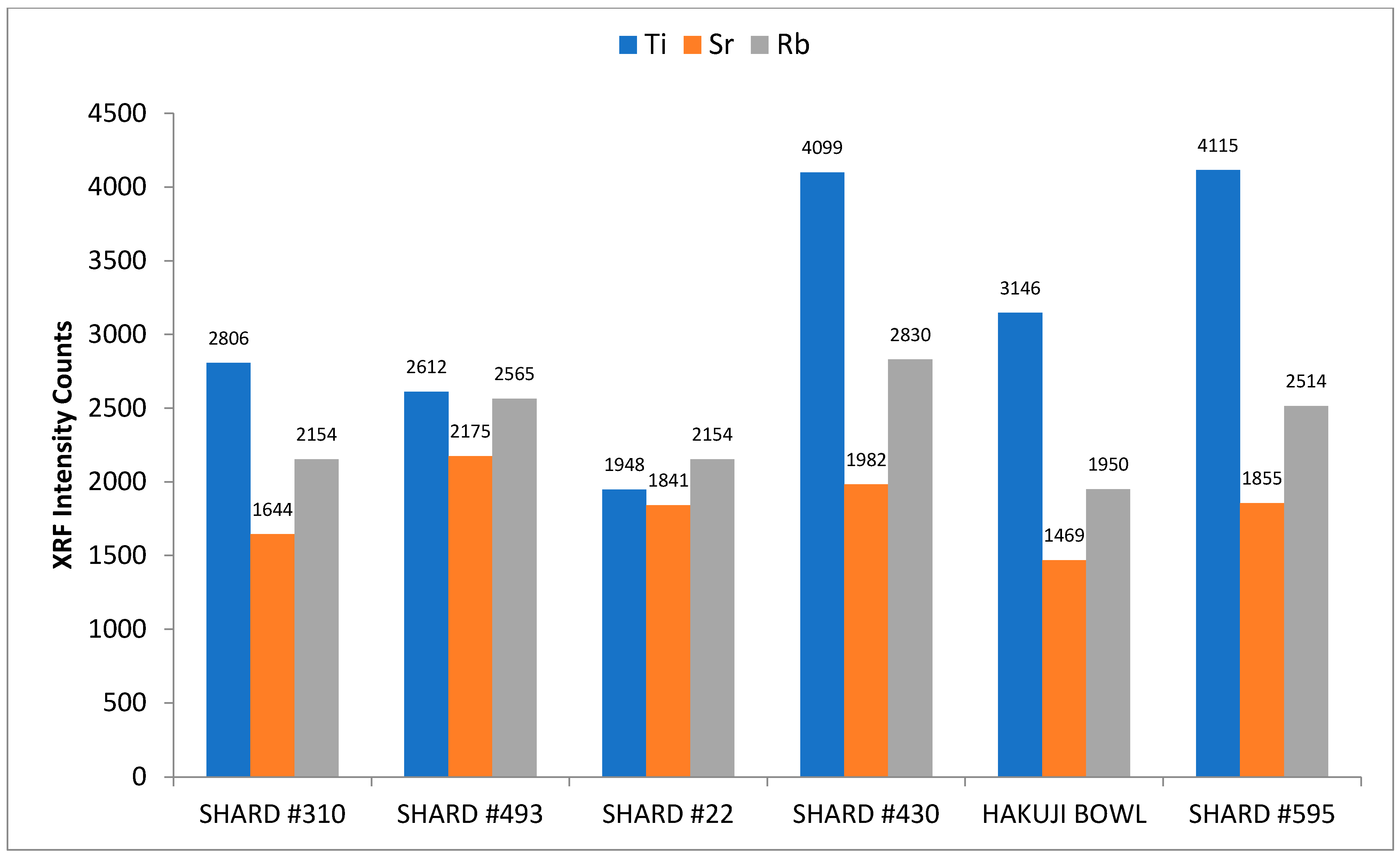

| Example | Shard #310 | Shard #493 | Shard #22 | Shard #430 | Hakuji Bowl | Shard #595 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rb/Sr ratio | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.45 |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

| Early 1640s | Mid-1640s | Mid-1640s | Late 1640s | 1650 Middle Period | 1652 Late Period |

| Example | Hakuji Bowl | Lobster | Scattered Treasures and Heron | Old Tree and White Cloud | Shard #595 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rb/Sr ratio | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.45 |

|  |  |  |  | |

| 1650 Middle Period | 1650 Middle Period | 1650 Middle Period | 1651 Middle Period | 1652 Late Period |

| Example | Shard #310 | Shard #493 | Shard #22 | Shard #430 | Hakuji Bowl | Shard #595 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti/Rb ratio | 1.30 | 1.02 | 0.9 | 1.45 | 1.61 | 1.63 |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

| Early 1640s | Mid-1640s | Mid-1640s | Late 1640s | 1650 Middle Period | 1652 Late Period |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montanari, R.; Murase, H.; Alberghina, M.F.; Schiavone, S.; Pelosi, C. The Origin of KO-KUTANI Porcelain—Part II: The Unearthed Secrets of the Hakuji Shallow Bowl. Coatings 2025, 15, 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15091007

Montanari R, Murase H, Alberghina MF, Schiavone S, Pelosi C. The Origin of KO-KUTANI Porcelain—Part II: The Unearthed Secrets of the Hakuji Shallow Bowl. Coatings. 2025; 15(9):1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15091007

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontanari, Riccardo, Hiroharu Murase, Maria Francesca Alberghina, Salvatore Schiavone, and Claudia Pelosi. 2025. "The Origin of KO-KUTANI Porcelain—Part II: The Unearthed Secrets of the Hakuji Shallow Bowl" Coatings 15, no. 9: 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15091007

APA StyleMontanari, R., Murase, H., Alberghina, M. F., Schiavone, S., & Pelosi, C. (2025). The Origin of KO-KUTANI Porcelain—Part II: The Unearthed Secrets of the Hakuji Shallow Bowl. Coatings, 15(9), 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15091007