Thermo-Chemo-Mechanical Coupling in TGO Growth and Interfacial Stress Evolution of Coated Dual-Pipe System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conservation Laws in TBCs

2.2. Constitutive Equations

2.3. Oxygen Diffusion Model

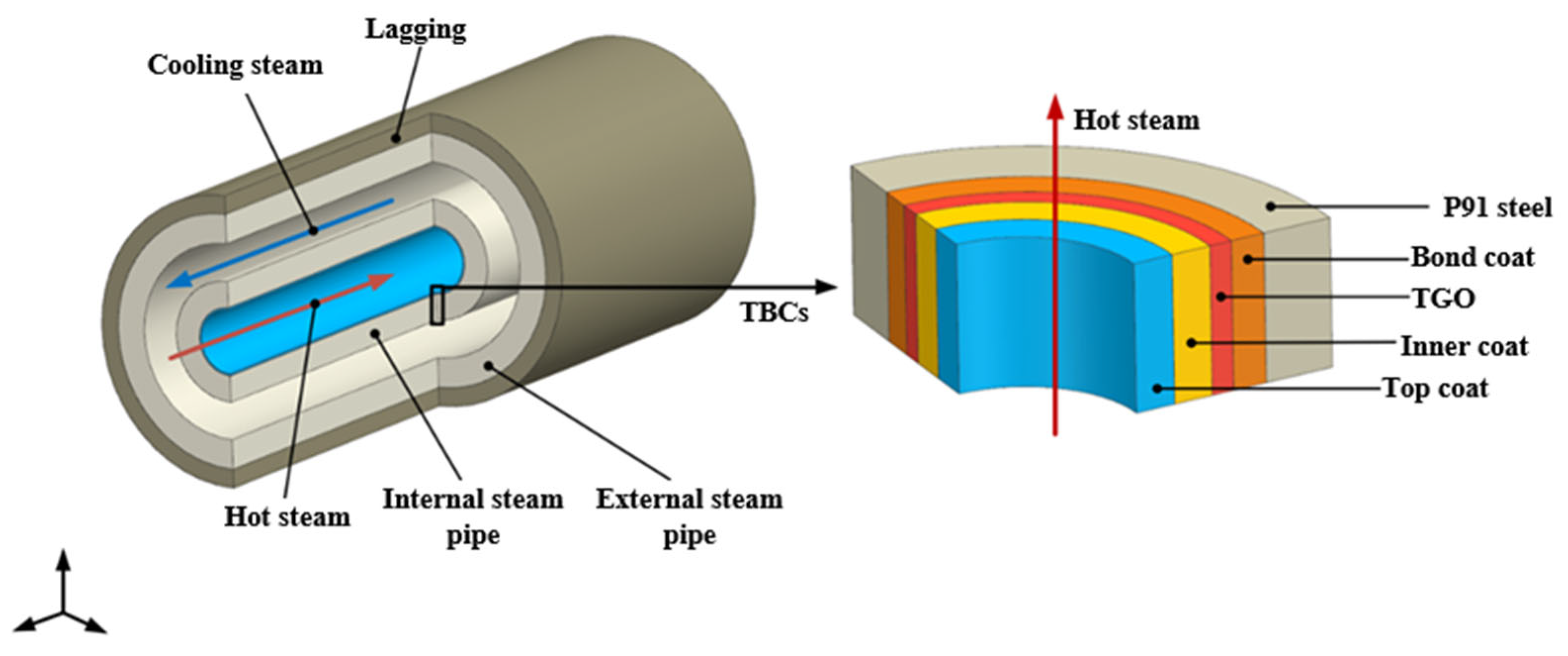

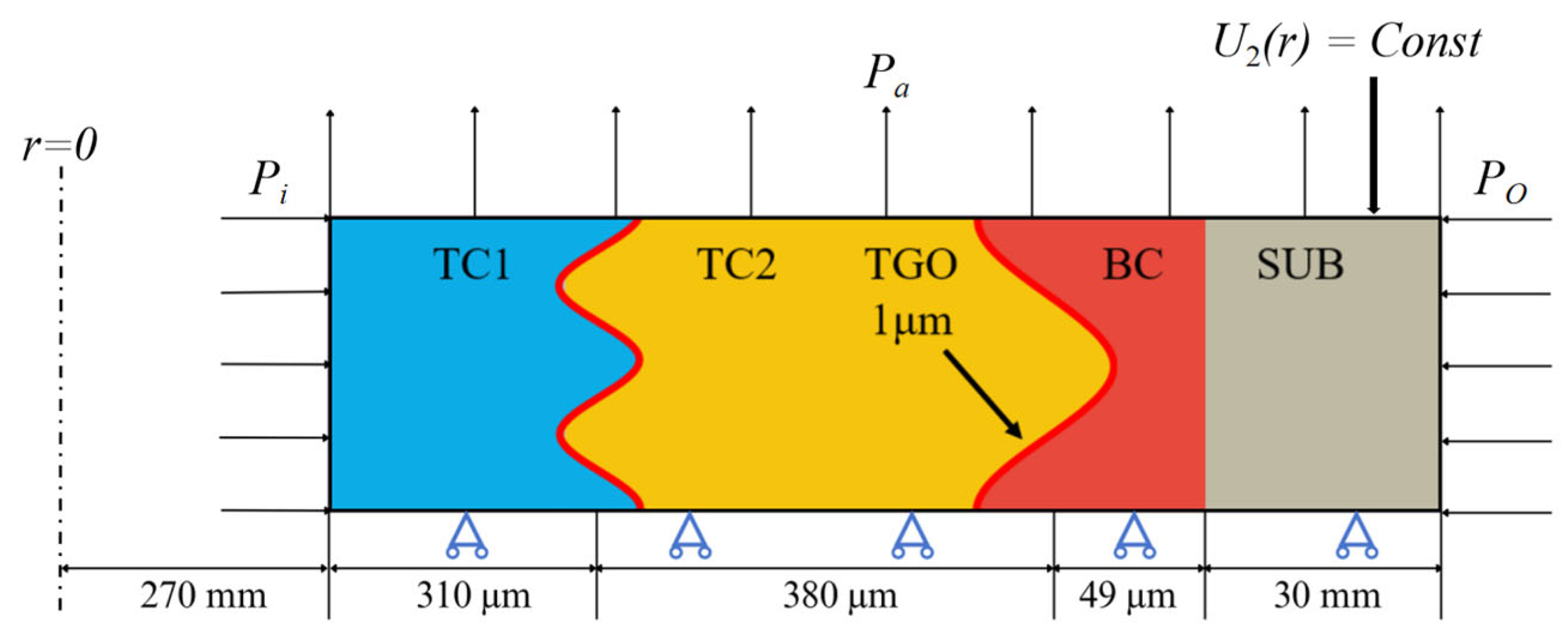

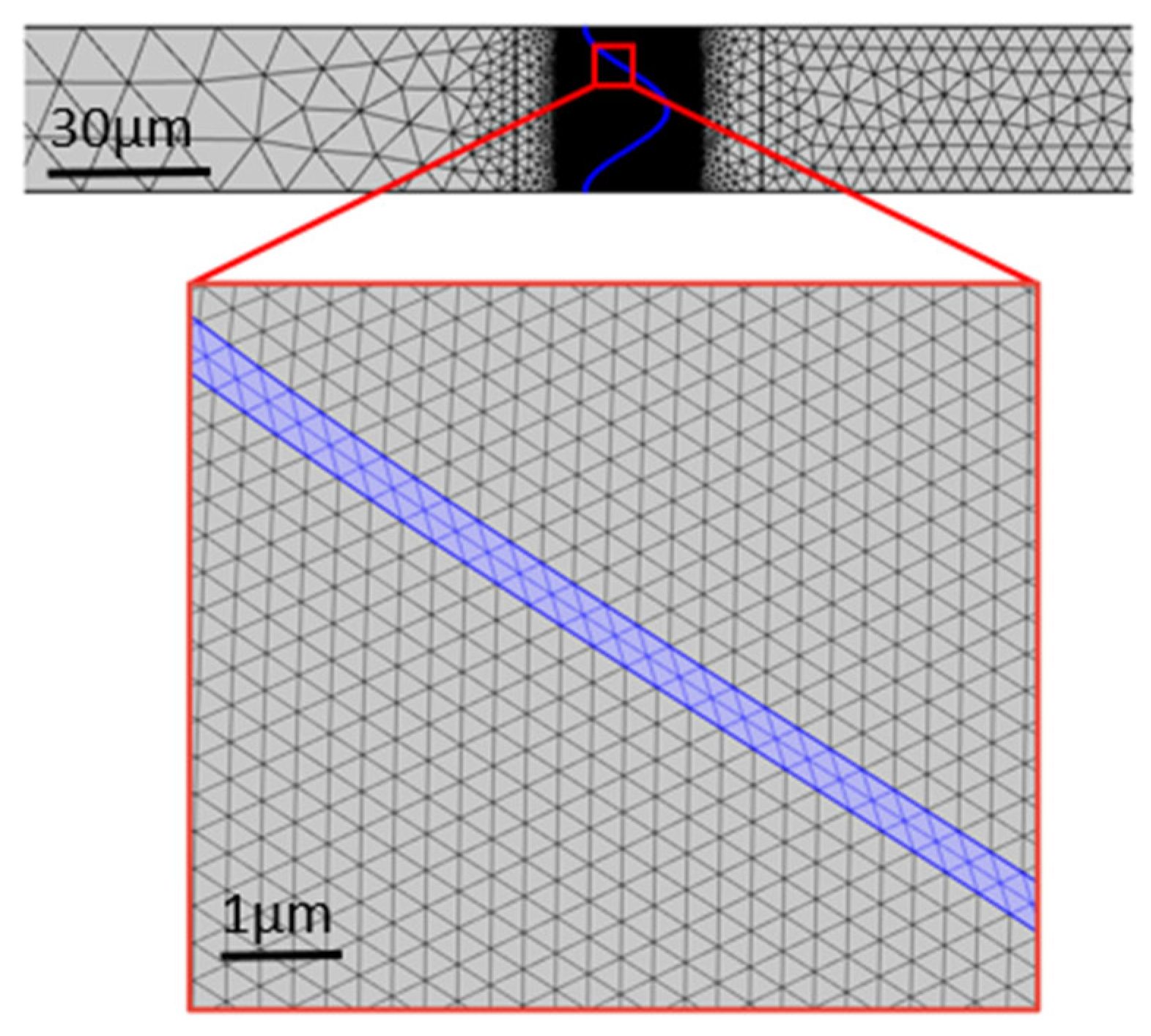

3. Finite Element Model of Dual-Pipe Coating System

3.1. Geometric Model and Mesh Generation

3.2. Material Parameters and Boundary Conditions

4. Results and Discussion

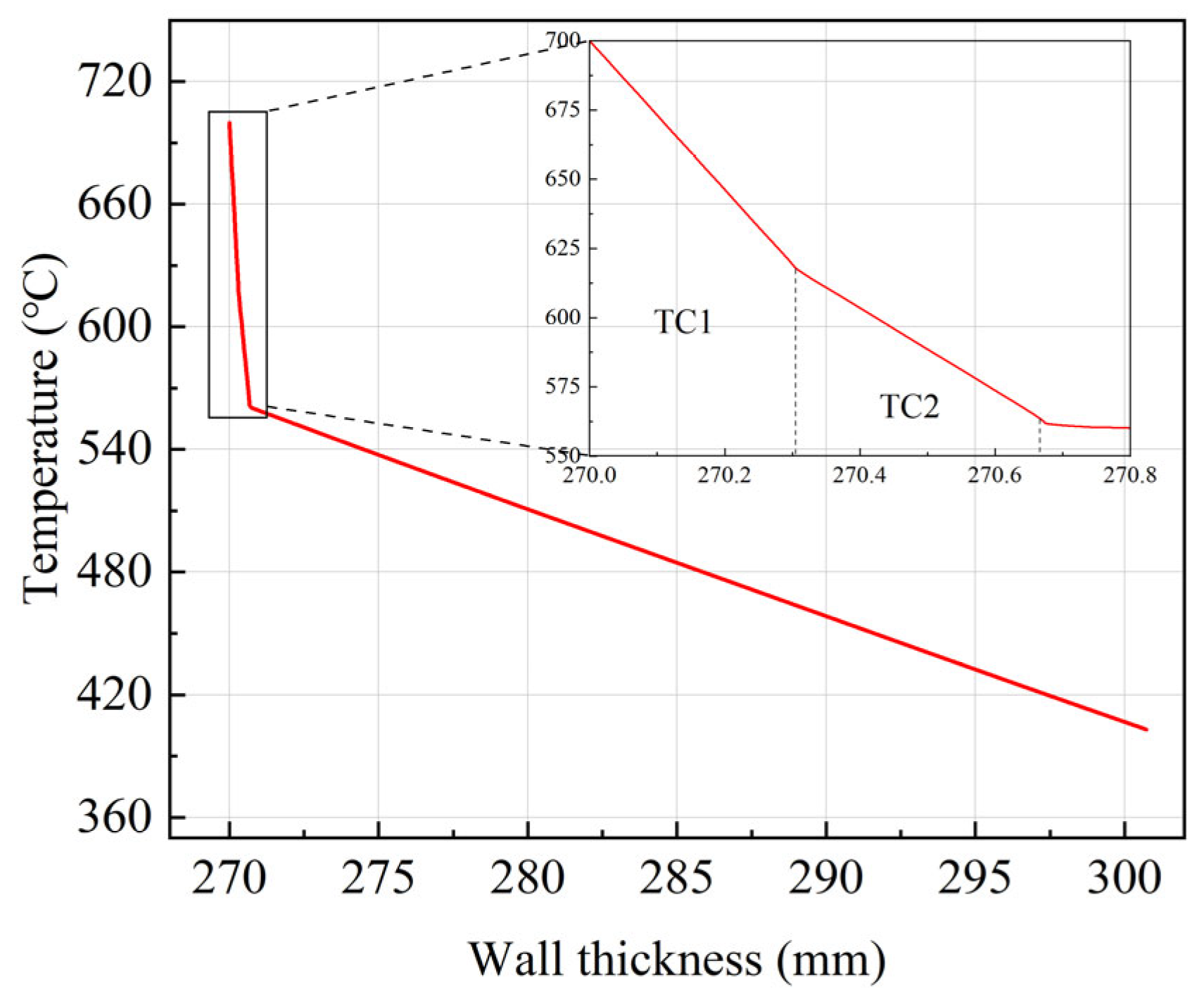

4.1. Steady-State Heat Transfer Analysis of Dual-Pipe Coating System

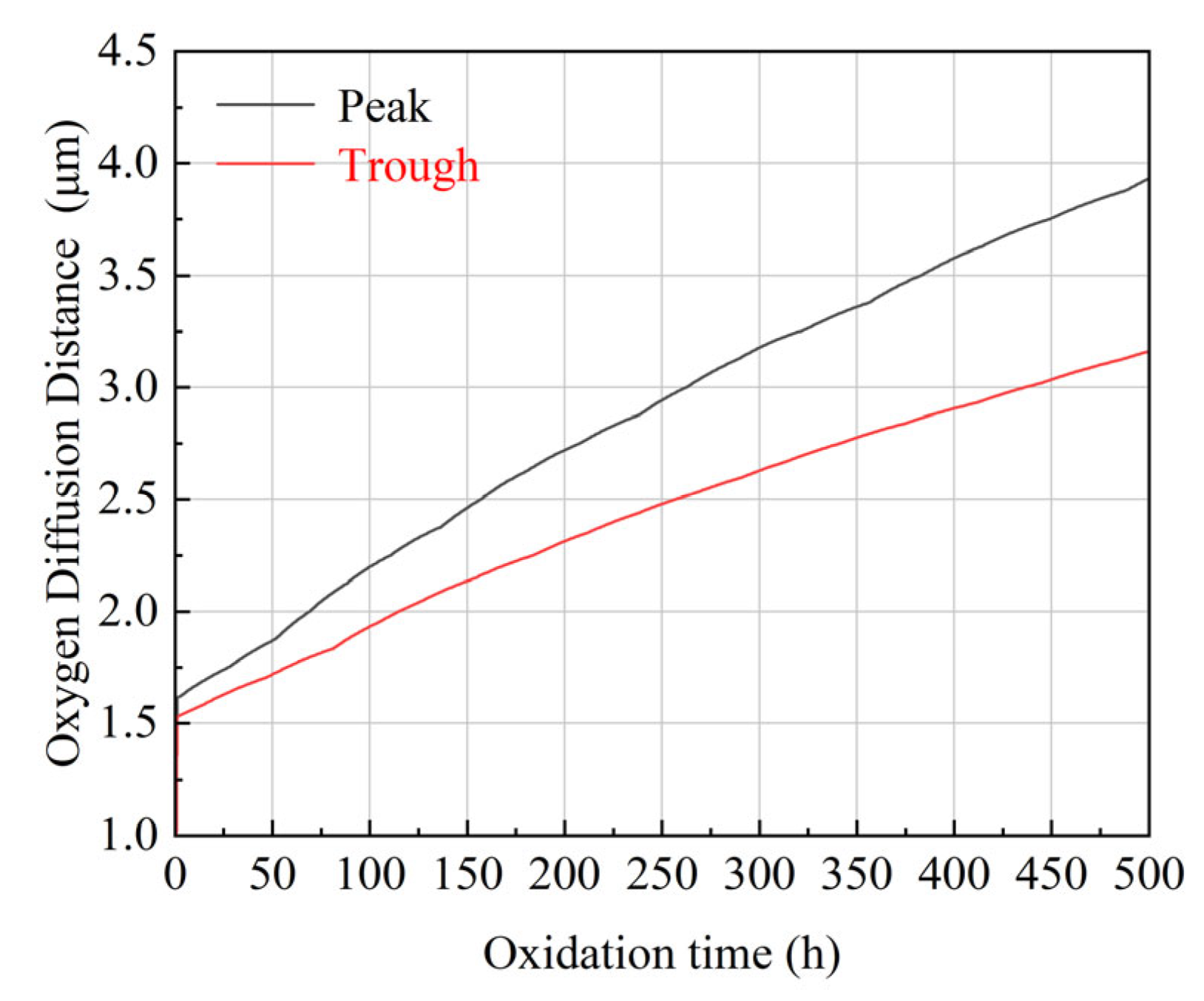

4.2. Oxygen Diffusion Characteristics

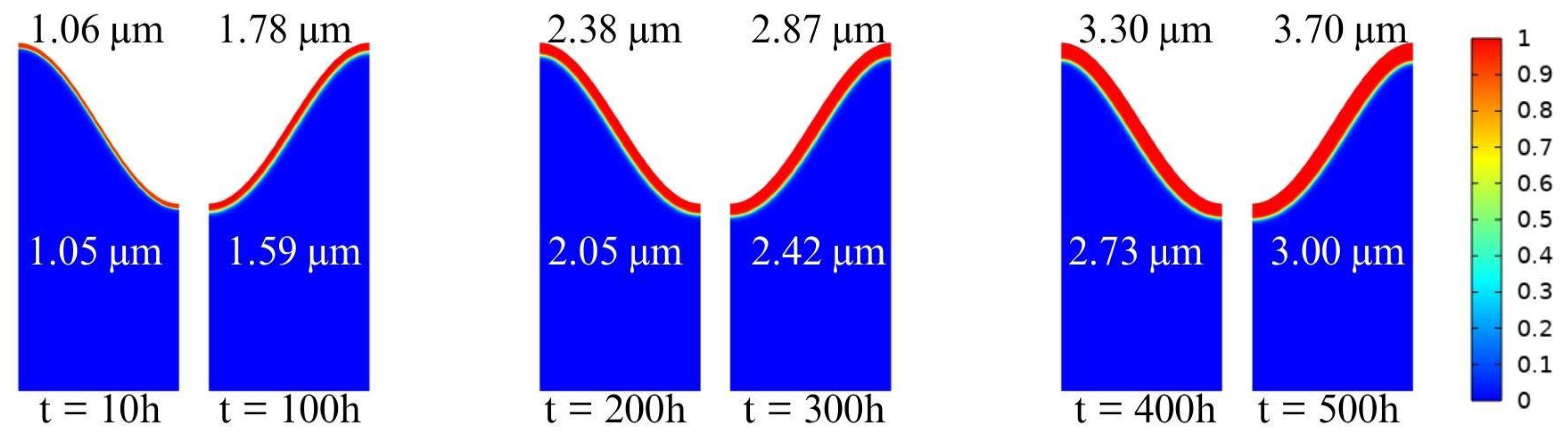

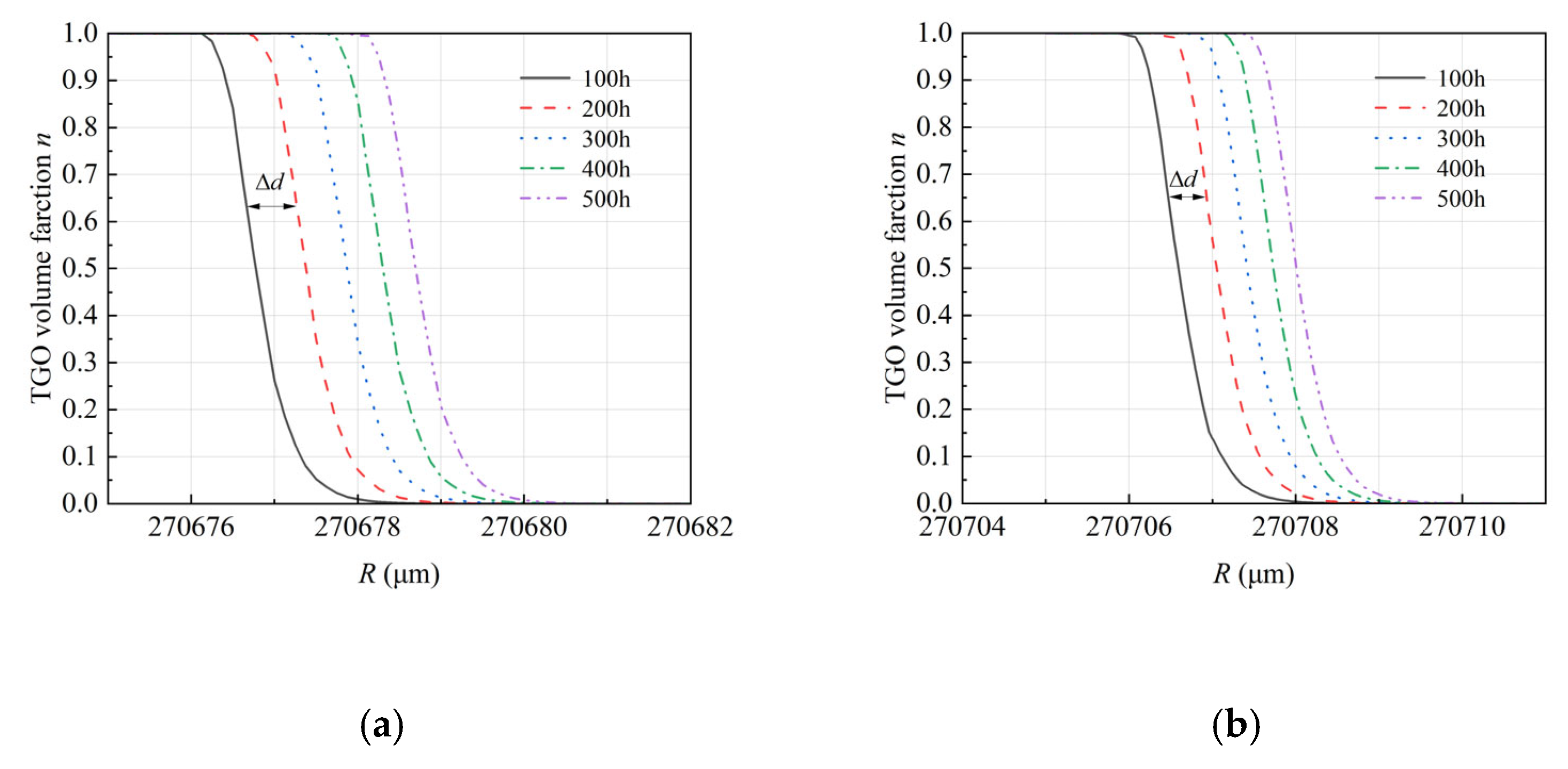

4.3. Thermo-Chemo-Mechanical Coupling Growth of TGO

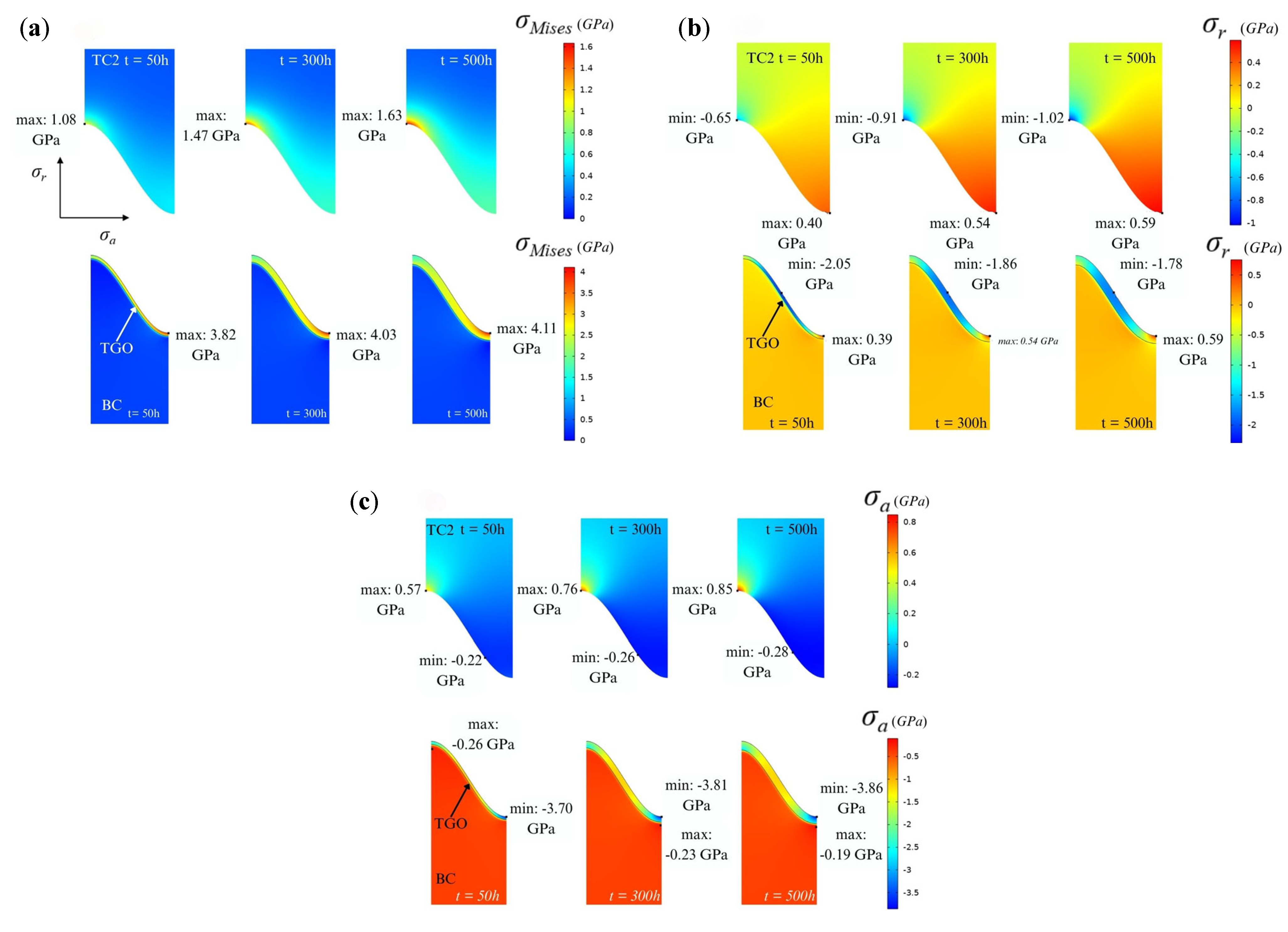

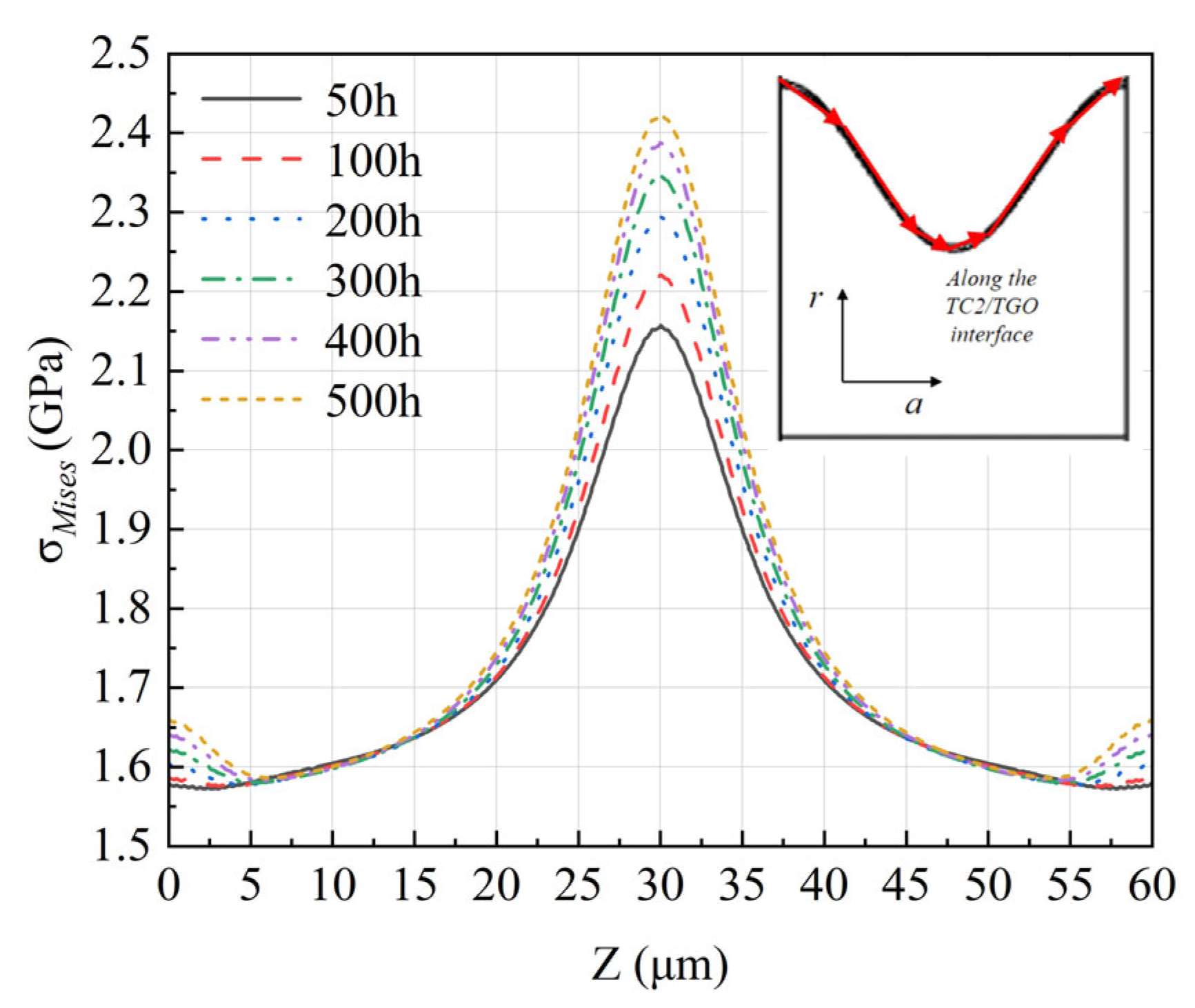

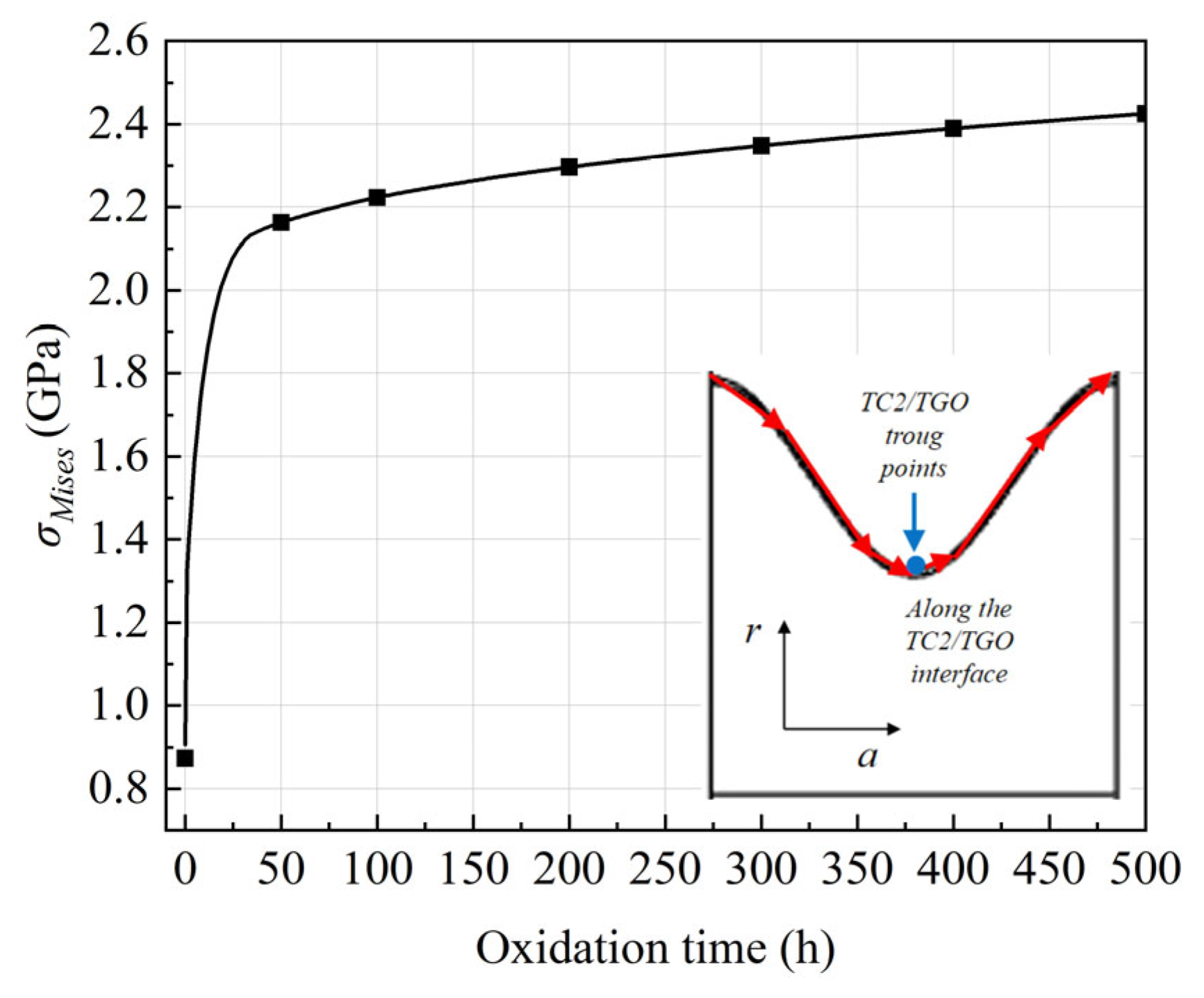

4.4. Stress Distribution and Evolution at Interfaces

5. Concluding Remarks

- The dual-pipe architecture effectively mitigates thermal loads through a significant thermal gradient. Under steady-state conditions with internal steam at 700 °C, the surface temperature of the inner P91 steel pipe is reduced to 560 °C. This thermal reduction confirms the system’s capability to utilize ferritic steels in advanced USC environments without requiring nickel-based alloy upgrades.

- The growth of TGO follows the parabolic growth kinetics but exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity driven by geometric curvature. The simulation reveals that oxygen diffusion flux is concentrated at interfacial peaks, resulting in a 23% thicker TGO at the peaks than at the troughs after 500 h. This confirms that interface morphology is a governing factor in local oxidation kinetics.

- The evolution of interfacial stress is dominated by the synergism between thermal mismatch and constrained volumetric expansion. This study identifies that axial stress significantly exceeds radial stress, with a 49% increase in axial stress at the TGO peaks over 500 h. This stress escalation is attributed to the incompatible growth strains within the TGO layer, which are constrained by the adjacent TC and BC.

- TGO evolution is a fully coupled thermo-chemo-mechanical process where growth stresses eventually surpass initial thermal mismatch stresses. The stress concentration identified at the wave peaks suggests these regions are the primary initiation sites for vertical cracking and subsequent spallation. These findings provide a theoretical basis for optimizing coating surface textures to enhance the structural integrity of high-temperature energy systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, X.F.; Benaarbia, A.; Sun, W.; Becker, A.; Morris, A.; Pavier, M.; Flewitt, P.; Tierney, M.; Wales, C. Optimisation and thermo-mechanical analysis of a coated steam dual pipe system for use in advanced ultra-supercritical power plant. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2020, 186, 104157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Stein, P.; Bai, Y.; Al-Siraj, M.; Yang, Y.; Xu, B.-X. A review on modeling of electro-chemo-mechanics inlithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2019, 413, 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.C.; Liu, Q.X.; Yang, L.; Wu, D.J.; Mao, W.G. Failure mechanisms and life prediction of thermal barrier coatings. Chin. J. Solid Mech. 2010, 31, 504–531. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.J.; Fan, X.L.; Sun, Y.L.; Su, L.; Song, Y.; Lv, B. The stresses and cracks in thermal barrier coating system: A review. Chin. J. Solid Mech. 2016, 37, 67647717. [Google Scholar]

- Freborg, A.M.; Ferguson, B.L. Modeling oxidation induced stresses in thermal barrier coatings. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1998, 245, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, A.M.; Evans, A.G. A numerical model forthe cyclic instability of thermally grown oxides inthermal barrier systems. Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 1793–1804. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, A.M.; Evans, A.G. A model study of displacement instabilities during cyclic oxidation. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.Y.; Hutchinson, J.W.; Evans, A.G. Large deformation simulations of cyclic displacement instabilities in thermal barrier systems. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 1063–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.Y.; Hutchinson, J.W.; Evans, A.G. Simulation of stresses and delamination in a plasma-sprayed thermal barrier system upon thermal cycling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 345, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hille, T.S.; Turteltaub, S.; Suiker, A.S.J. Oxide growth and damage evolution in thermal barrier coatings. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2011, 78, 2139–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffel, K.; Anand, L. A chemo-thermo-mecha nically coupled theory for elastic-viscoplastic deformation, diffusion, and volumetric swelling due to a chemical reaction. Int. J. Plast. 2011, 27, 1409–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffel, K.; Anand, L.; Gasem, Z.M. On modeling the oxidation of high-temperature alloys. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.L.; Shen, S.P. Non-equilibrium thermodynamics and variational principles for fully coupled thermal-mechanical-chemical processes. Acta Mech. 2013, 224, 2895–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.N.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Y.C.; Pi, Z.; Zhu, W. A chemo-thermo-mechanically constitutive theory for thermal barrier coatings under CMAS infiltration and corrosion. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2019, 133, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Zhong, Z. A coupled theory for chemically active and deformable solids with mass diffusion and heat conduction. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2017, 107, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Zhong, Z. A diffusion–reaction–deformation coupling model for lithiation of silicon electrodes considering plastic flow at large deformation. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2021, 91, 2713–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.C.; Hashida, T. Coupled effects of temperature gradient and oxidation on thermal stress in thermal barrier coating system. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2001, 38, 4235–4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Zhu, P.P.; Zhong, Z. A chemo-mechanically coupled continuum damage-healing model for chemical reaction-based self-healing materials. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2022, 236–237, 111346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Suo, Y.H.; Shen, S.P. Reaction–diffusion–stress coupling effect in inelastic oxide scale during oxidation. Oxide Scale Dur. Oxid. 2015, 83, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.E. Stress effects in high temperature oxidation of metals. Int. Mater. Rev. 1995, 40, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.F.; Zhang, Z.L.; Qin, L.; Yuan, B.; Gao, J.X.; Pang, Z.Q. Key characteristic parameters analysis and structure optimization design of 700 °C new coating double tube system. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2023, 52, 3757–3766. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Q.; Li, S.Z.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, T. Coupled mechanical-oxidation modeling during oxidation of thermal barrier coatings. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 154, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.Y.; Meguid, S.A. Modeling and characterisation of depletion of aluminium in bond coat and growth of mixed oxides in thermal barrier coatings. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2020, 16, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Wang, K.; Guo, X.; Gao, J.; Chen, P.N. Nonlinear Oxidation Behavior at Interfaces in Coated Steam Dual-Pipe with Initial Waviness and Cooling Temperature. Coatings 2024, 14, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q. Theoretical Research of Large Deformation Thermo-Chemo-Mechanical Coupled Growth and Failure during Thermal Barrier Coatings Interface Oxidation. Doctoral Dissertation, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.Q.; Yang, L.; Nie, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y. A chemo-thermo-mechanically constitutive theory of high-temperature interfacial oxidation in alloys under deformation. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2023, 66, 1018–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.G.; Mumm, D.R.; Hutchinson, J.W.; Meier, G.H.; Pettit, F.S. Mechanisms controlling the durability of thermal barrier coatings. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2001, 46, 505–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomimatsu, T.; Zhu, S.; Kagawa, Y. Effect of thermal exposure on stress distribution in TGO layer of EB-PVD TBC. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 2397–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padture, N.P.; Gell, M.; Jordan, E.H. Thermal barrier coatings for gas-turbine engine applications. Science 2002, 296, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, L.; Wang, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhao, D.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, P.; Yao, W.; Bui, T.Q. A chemo-thermo-mechanical coupled phase field framework for failure in thermal barrier coatings. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 411, 116044. [Google Scholar]

| T (°C) | E (GPa) | v | ρ (kg/m3) | α (10−6/°C) | kc (W/(m·°C)) | C (J/(kg·°C)) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC1 | - | 63 | 0.25 | 6300 | 9.1 | 0.87 | 460 |

| TC2 | 20 800 | 204 179 | 0.1 0.11 | 6037 | 9.68 9.88 | 1.2 | 500 |

| TGO | 20 1000 | 400 325 | 0.23 0.25 | 3984 | 8 9.3 | 10 4 | 755 |

| BC | 20 800 | 200 145 | 0.3 0.32 | 7711 | 12.5 14.3 | 5.8 14.5 | 628 |

| SUB | 20 100 200 300 400 450 500 550 600 650 | 218 213 207 199 190 186 181 175 168 162 | 0.3 | 488 461 441 427 396 - 360 331 285 206 | - 10.9 11.3 11.7 12.1 12.1 12.3 12.4 12.6 12.7 | 26 27 28 28 29 29 30 30 30 30 | 440 480 510 550 630 630 660 710 770 860 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, W.; Wu, T.; Gao, J.; Guo, X.; Yuan, B.; Lv, K. Thermo-Chemo-Mechanical Coupling in TGO Growth and Interfacial Stress Evolution of Coated Dual-Pipe System. Coatings 2025, 15, 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121498

Song W, Wu T, Gao J, Guo X, Yuan B, Lv K. Thermo-Chemo-Mechanical Coupling in TGO Growth and Interfacial Stress Evolution of Coated Dual-Pipe System. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121498

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Weiao, Tianliang Wu, Junxiang Gao, Xiaofeng Guo, Bo Yuan, and Kun Lv. 2025. "Thermo-Chemo-Mechanical Coupling in TGO Growth and Interfacial Stress Evolution of Coated Dual-Pipe System" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121498

APA StyleSong, W., Wu, T., Gao, J., Guo, X., Yuan, B., & Lv, K. (2025). Thermo-Chemo-Mechanical Coupling in TGO Growth and Interfacial Stress Evolution of Coated Dual-Pipe System. Coatings, 15(12), 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121498