A Study of Speckle Materials for Digital Image Correlation (DIC): Thermal Stability and Color Change Mechanisms at High Temperatures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experiments

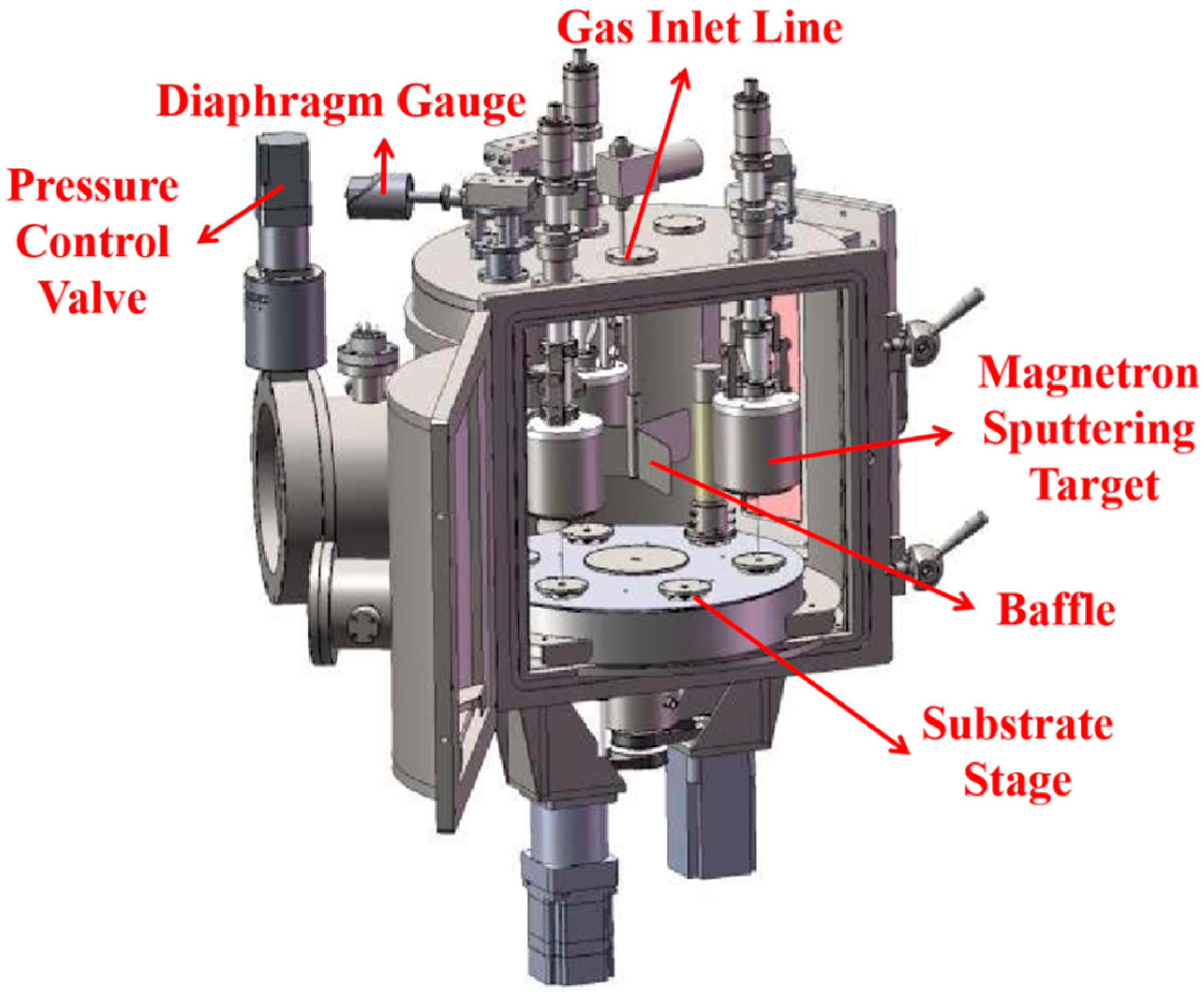

2.1. Magnetron Sputtering Film Preparation

2.2. High-Temperature Test and Analysis

2.3. Mechanisms of Color Change

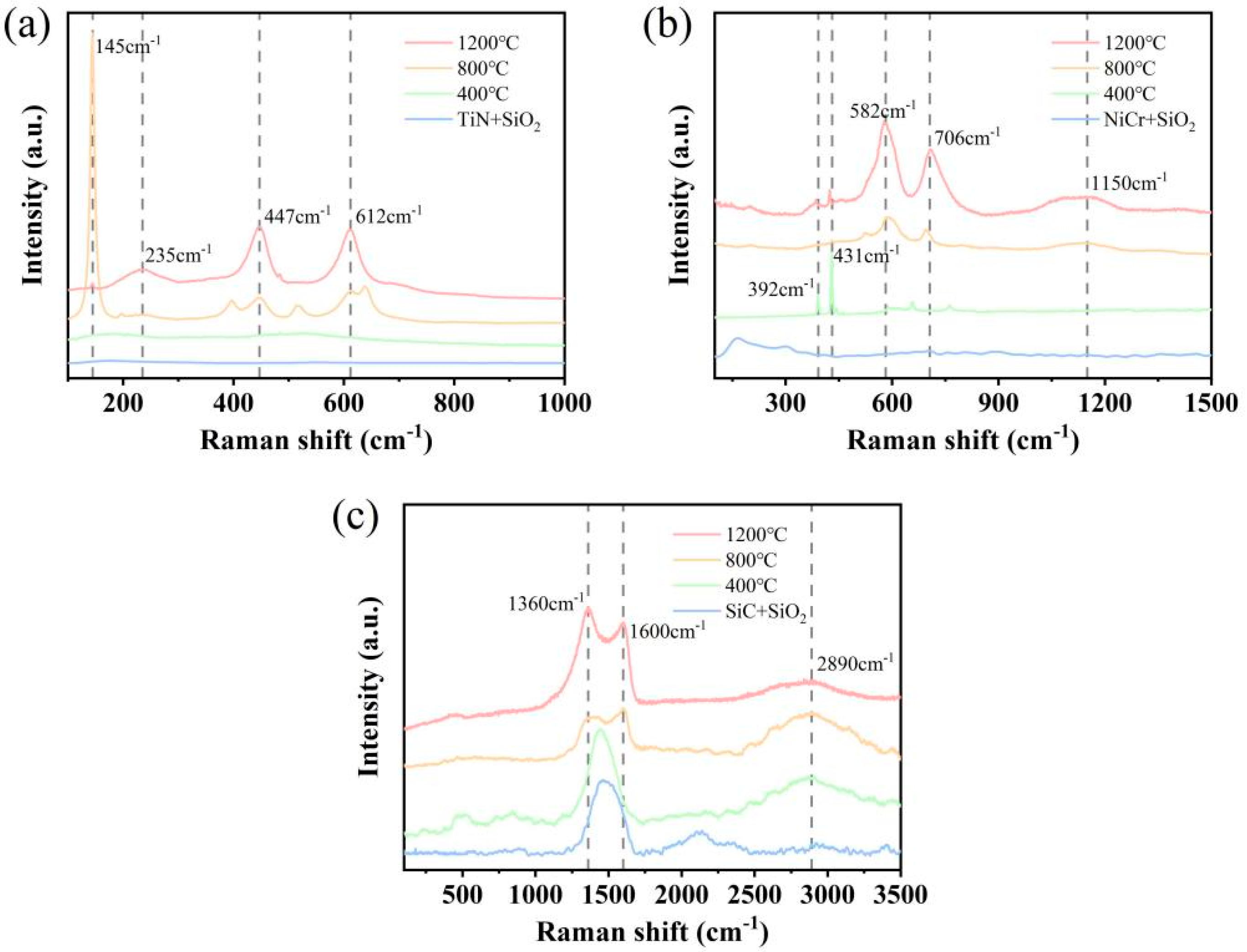

2.3.1. Raman Spectra Analysis

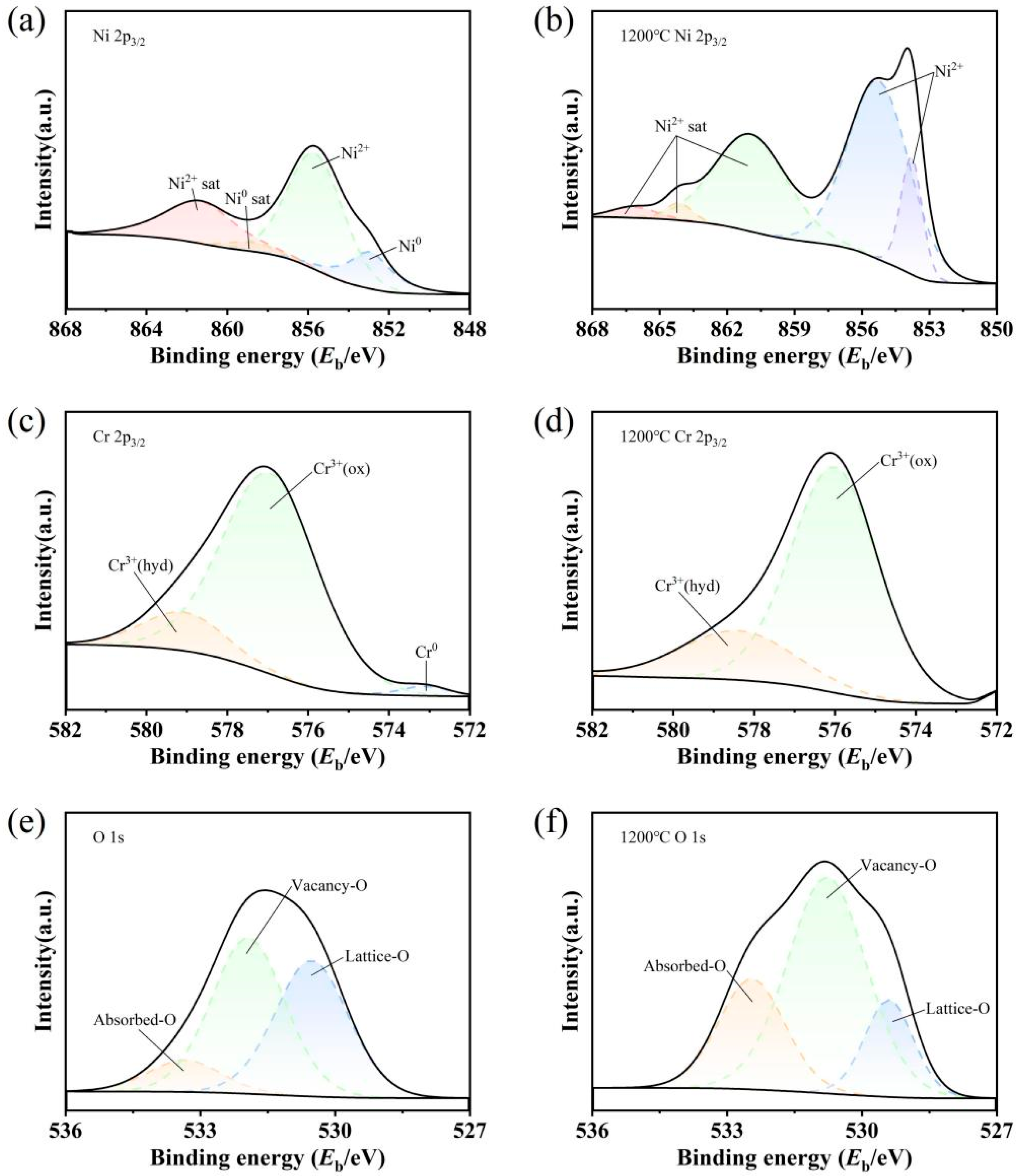

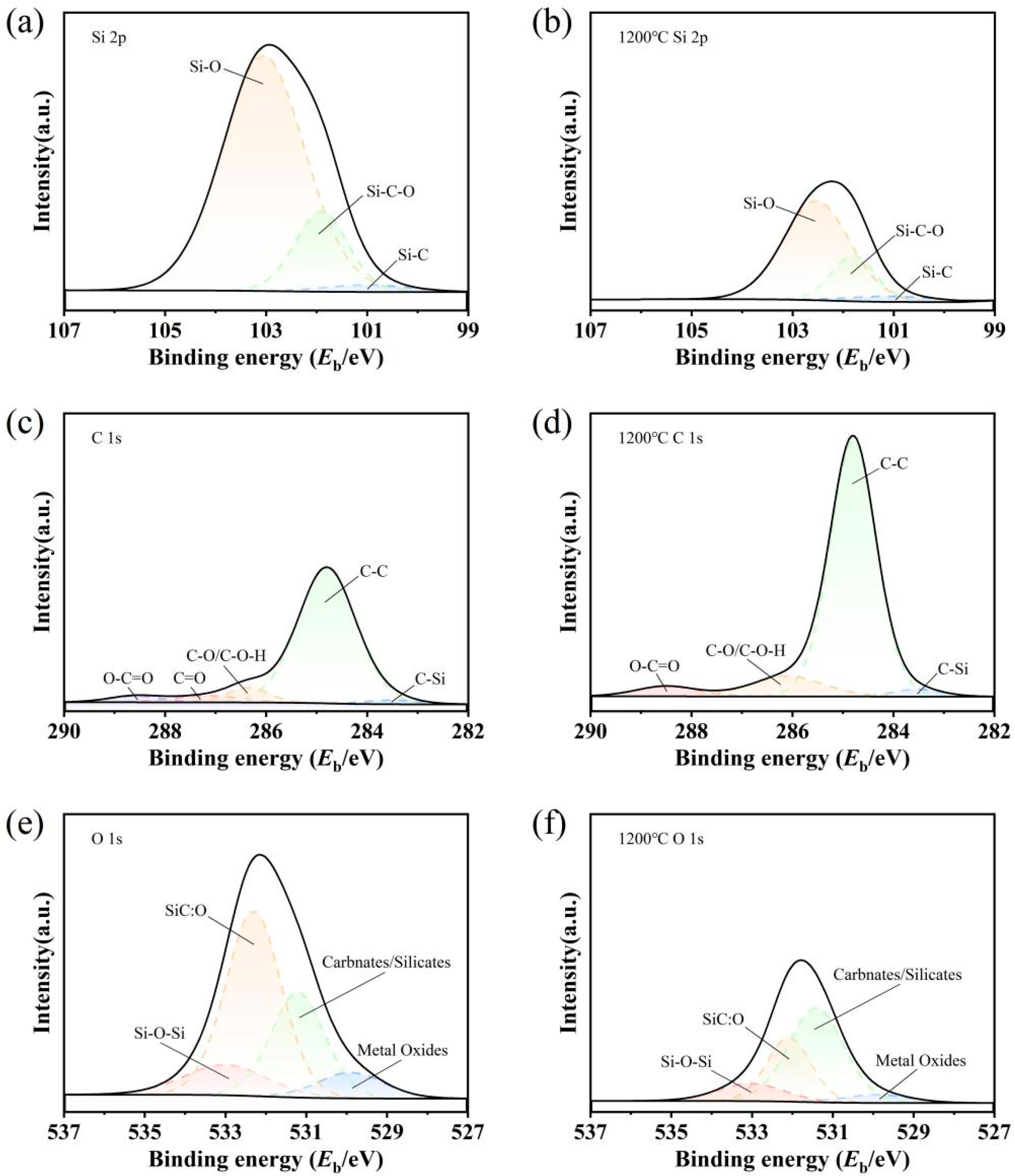

2.3.2. XPS Analysis

2.4. SiO2 Film

2.4.1. Raman Spectra Analysis

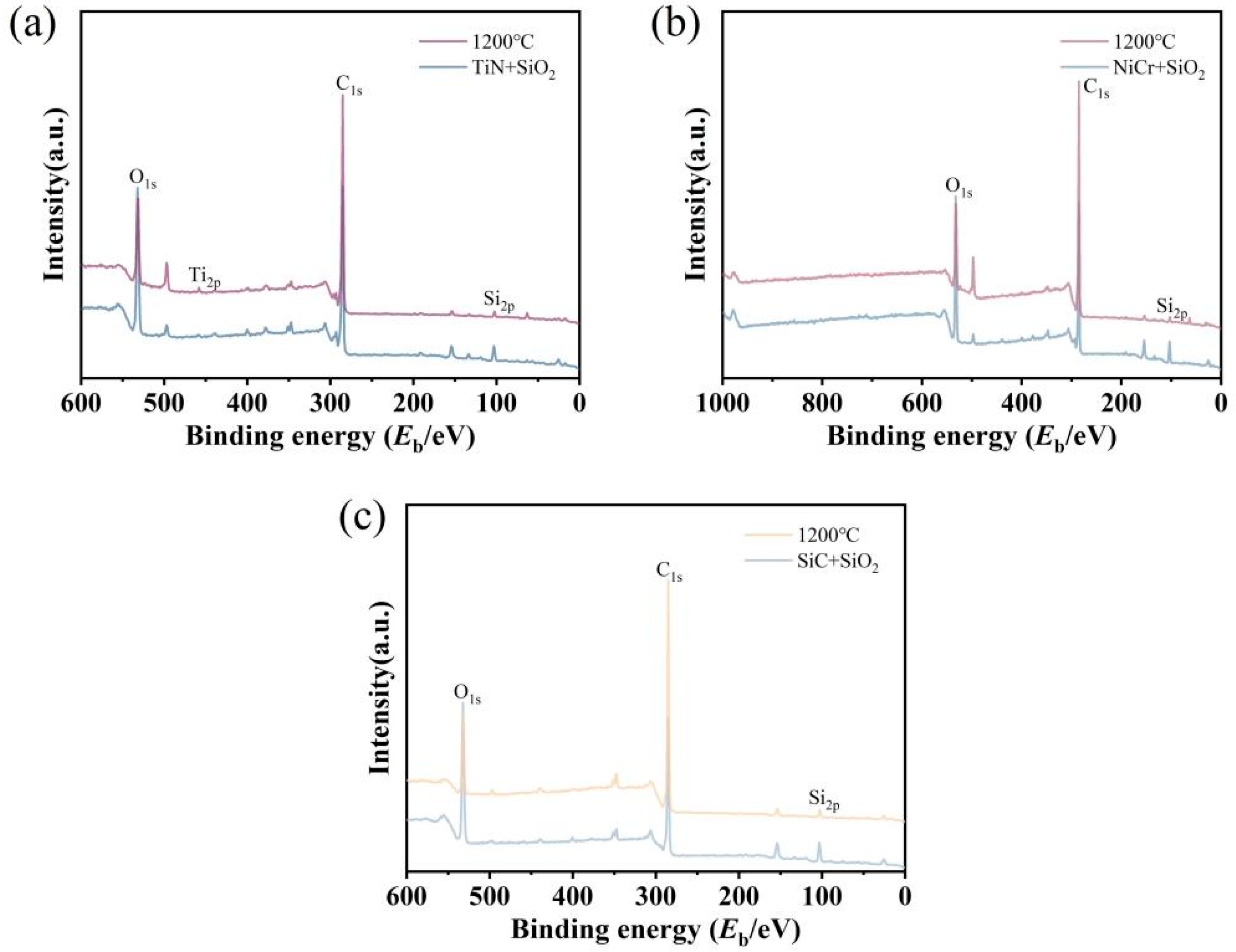

2.4.2. XPS Analysis

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pan, B.; Jiang, T.; Wu, D. Strain measurement of objects subjected to aerodynamic heating using digital image correlation: Experimental design and preliminary results. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2014, 85, 115102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Pan, B. Overview of High-temperature Deformation Measurement Using Digital Image Correlation. Exp. Mech. 2021, 61, 1121–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.M.; Goo, N.S. High-Temperature DIC Deformation Measurement under High-Intensity Blackbody Radiation. Aerospace 2024, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreis, T. Digital holographic interference-phase measurement using the Fourier-transform method. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1986, 3, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fang, D.; Xie, H.; Lee, J.J. Study of effect of 90° domain switching on ferroelectric ceramics fracture using the moiré interferometry. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 3911–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xie, X.; Zhu, L.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. Review of electronic speckle pattern interferometry (ESPI) for three dimensional displacement measurement. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2014, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassini, R.; Rossi, G.; Brouckaert, J.F. On the development of a magnetoresistive sensor for blade tip timing and blade tip clearance measurement systems. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016, 87, 102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, W.H.; Ranson, W.F. Digital Imaging Techniques In Experimental Stress Analysis. Opt. Eng. 1982, 21, 213427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, M.A.; Wolters, W.J.; Peters, W.H.; Ranson, W.F.; McNeill, S.R. Determination of displacements using an improved digital correlation method. Image Vis. Comput. 1983, 1, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.C.; Ranson, W.F.; Sutton, M.A. Applications of digital-image-correlation techniques to experimental mechanics. Exp. Mech. 1985, 25, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Qian, K.; Xie, H.; Asundi, A. Two-dimensional digital image correlation for in-plane displacement and strain measurement: A review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 062001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.L.; Pan, B. A Review of Speckle Pattern Fabrication and Assessment for Digital Image Correlation. Exp. Mech. 2017, 57, 1161–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lan, S.; Li, J.; Fang, Q.; Ren, Y.; He, W.; Xie, H. Digital image correlation in extreme conditions. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 205, 112589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Wu, D.; Wang, Z.; Xia, Y. High-temperature digital image correlation method for full-field deformation measurement at 1200 °C. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 015701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yao, X.F.; Su, Y.Q.; Liu, W. The feasibility and application of gray scale adjustment method in high temperature digital image correlation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2017, 28, 025201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.M.C.; Reu, P.L. Distortion of Digital Image Correlation (DIC) Displacements and Strains from Heat Waves. Exp. Mech. 2018, 58, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Rui, X. A Correction Method for Heat Wave Distortion in Digital Image Correlation Measurements Based on Background-Oriented Schlieren. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yao, X.F.; Su, Y.Q.; Ma, Y.J. High temperature image correction in DIC measurement due to thermal radiation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2015, 26, 095006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yue, M.; Qu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Takagi, K.; Fang, X.; Feng, X. High-temperature DIC based on aluminium dihydrogen phosphate speckle. Measurement 2019, 133, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, R.; Dupré, J.-C.; Doumalin, P.; Pop, O.; Teixeira, L.; Huger, M. High-temperature digital image correlation techniques for full-field strain and crack length measurement on ceramics at 1200 °C: Optimization of speckle pattern and uncertainty assessment. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2021, 146, 106716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Arévalo, F.M.; Pulos, G. Use of digital image correlation to determine the mechanical behavior of materials. Mater. Charact. 2008, 59, 1572–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.D.; Zok, F.W. High-temperature materials testing with full-field strain measurement: Experimental design and practice. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2011, 82, 115101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Wu, D.; Gao, J. High-temperature strain measurement using active imaging digital image correlation and infrared radiation heating. J. Strain Anal. Eng. Des. 2014, 49, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xie, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J. Fabrication of micro-scale speckle pattern and its applications for deformation measurement. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2012, 23, 035402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsen, A. Characterization of Local Strain Fields in Cross-Ply Composites Under Transverse Loading. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karanjgaokar, N.J.; Oh, C.S.; Chasiotis, I. Microscale Experiments at Elevated Temperatures Evaluated with Digital Image Correlation. Exp. Mech. 2011, 51, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, G.J.; Sehitoglu, H. Experimental Methodology for Studying Strain Heterogeneity with Microstructural Data from High Temperature Deformation. Exp. Mech. 2015, 55, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Sutton, M.A.; Li, X.; Schreier, H.W. Full-field Thermal Deformation Measurements in a Scanning Electron Microscope by 2D Digital Image Correlation. Exp. Mech. 2008, 48, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gioacchino, F.; Quinta Da Fonseca, J. Plastic Strain Mapping with Sub-micron Resolution Using Digital Image Correlation. Exp. Mech. 2013, 53, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guery, A.; Latourte, F.; Hild, F.; Roux, S. Characterization of SEM speckle pattern marking and imaging distortion by digital image correlation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 015401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yan, G.; He, G.; Chen, L. Fabrication and optimization of micro-scale speckle patterns for digital image correlation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2016, 27, 015203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, H.; Luo, Q.; Gu, C.; Hu, Z.; Chen, P.; Zhang, Q. Fabrication technique of micro/nano-scale speckle patterns with focused ion beam. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2012, 55, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Sockalingam, S.; O’brien, H.; Yang, G.; El Loubani, M.; Lee, D.; Sutton, M.A. Sub-microscale speckle pattern creation on single carbon fibers for scanning electron microscope-digital image correlation (SEM-DIC) experiments. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 165, 107331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, J.T. Physics and technology of magnetron sputtering discharges. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.J.; Arnell, R.D. Magnetron sputtering: A review of recent developments and applications. Vacuum 2000, 56, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Garah, M.; Soubane, D.; Sanchette, F. Review on mechanical and functional properties of refractory high-entropy alloy films by magnetron sputtering. Emergent Mater. 2024, 7, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefnagels, J.P.M.; Van Maris, M.P.F.H.L.; Vermeij, T. One-step deposition of nano-to-micron-scalable, high-quality digital image correlation patterns for high-strain in-situ multi-microscopy testing. Strain 2019, 55, e12330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattox, D.M. Physical vapor deposition (PVD) processes. Met. Finish. 2002, 100, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.A. Vacuum Deposition onto Webs, Films, and Foils; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, G.S.; Ahn, S.M.; Hwang, N.-M. Effects of Sputtering Power, Working Pressure, and Electric Bias on the Deposition Behavior of Ag Films during DC Magnetron Sputtering Considering the Generation of Charged Flux. Electron. Mater. Lett. 2022, 18, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, A.G.; Scarisoareanu, M.; Morjan, I.; Dutu, E.; Badiceanu, M.; Mihailescu, I. Principal component analysis of Raman spectra for TiO2 nanoparticle characterization. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 417, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswathy, N.R.; Varghese, J.; Nair, S.R.; Kumar, R.V. Structural, optical, and magnetic properties of Mn-doped NiO thin films prepared by sol-gel spin coating. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 282, 125916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eda, Y.; Manaka, T.; Hanawa, T.; Chen, P.; Ashida, M.; Noda, K. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy-based valence band spectra of passive films on titanium. Surf. Interface Anal. 2022, 54, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, S.; Lu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, X. Oxidation behavior of a Ni-Cr-Fe superalloy from 800 °C to 1100 °C in air: Formation and mechanism of multilayer oxide films. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1020, 179393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, B.P.; Grosvenor, A.P.; Biesinger, M.C.; Kobe, B.A.; Mcintyre, N.S. Structure and growth of oxides on polycrystalline nickel surfaces. Surf. Interface Anal. 2007, 39, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosvenor, A.P.; Biesinger, M.C.; Smart, R.S.C.; Mcintyre, N.S. New interpretations of XPS spectra of nickel metal and oxides. Surf. Sci. 2006, 600, 1771–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, K.; Suresh, P.; Prabu, M.; Kavimani, V. Effect of graphene/silicon dioxide fillers addition on mechanical and thermal stability of epoxy glass fibre composite. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 9961–9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, N.A.; Patra, N.; Ni, N.; Jayaseelan, D.D.; Lee, W.E. Oxidation behaviour of SiC/SiC ceramic matrix composites in air. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36, 3293–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, J.A.; Tressler, R.E. Oxidation Kinetics of Silicon Carbide Crystals and Ceramics: I, In Dry Oxygen. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1986, 69, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Film Material | Room Temperature | 400 °C | 600 °C | 800 °C | 1000 °C | 1200 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| TiN |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Ta |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| NiCr |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| SiC |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Flim Material | Room Temperature | 400 °C | 800 °C | 1200 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiN/SiO2 |  |  |  |  |

| NiCr/SiO2 |  |  |  |  |

| SiC/SiO2 |  |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ni, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, H. A Study of Speckle Materials for Digital Image Correlation (DIC): Thermal Stability and Color Change Mechanisms at High Temperatures. Coatings 2025, 15, 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121444

Ni Y, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Zheng H. A Study of Speckle Materials for Digital Image Correlation (DIC): Thermal Stability and Color Change Mechanisms at High Temperatures. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121444

Chicago/Turabian StyleNi, Yunzhu, Yan Wang, Zhongya Zhang, and Huilong Zheng. 2025. "A Study of Speckle Materials for Digital Image Correlation (DIC): Thermal Stability and Color Change Mechanisms at High Temperatures" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121444

APA StyleNi, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., & Zheng, H. (2025). A Study of Speckle Materials for Digital Image Correlation (DIC): Thermal Stability and Color Change Mechanisms at High Temperatures. Coatings, 15(12), 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121444