The Cu Ions Releasing Behavior of Cu-Ti Pseudo Alloy Antifouling Anode Deposited by Cold Spray in Marine Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments and Methods

2.1. Cu Ions Releasing Rate Simulation

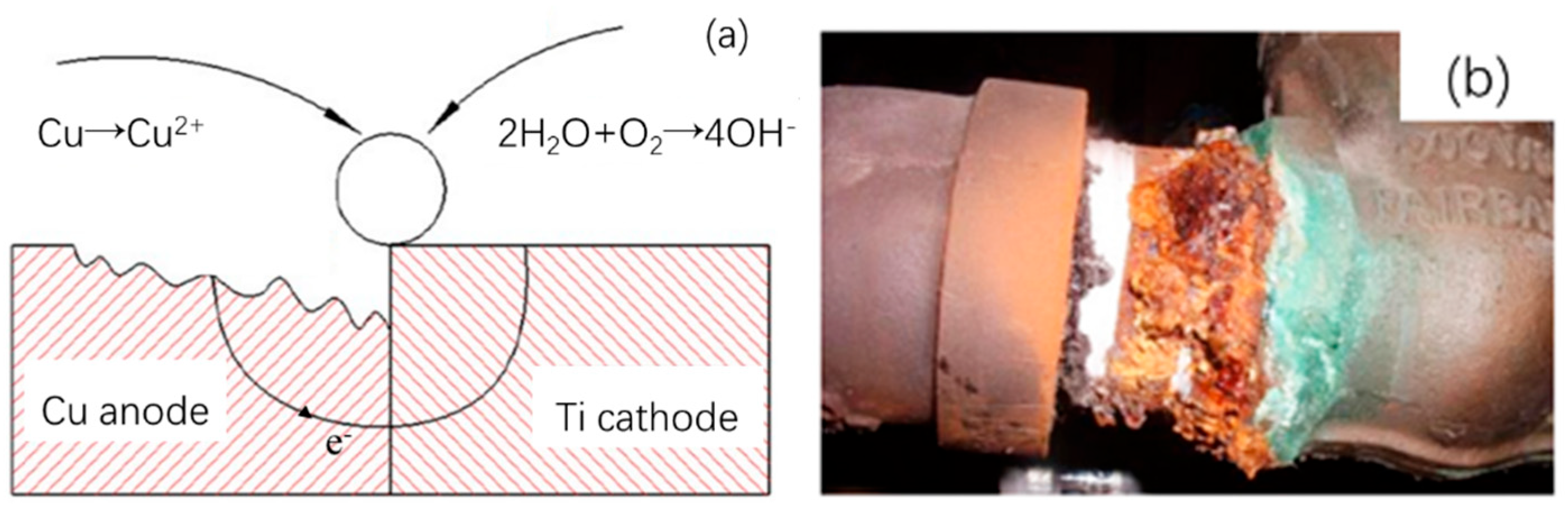

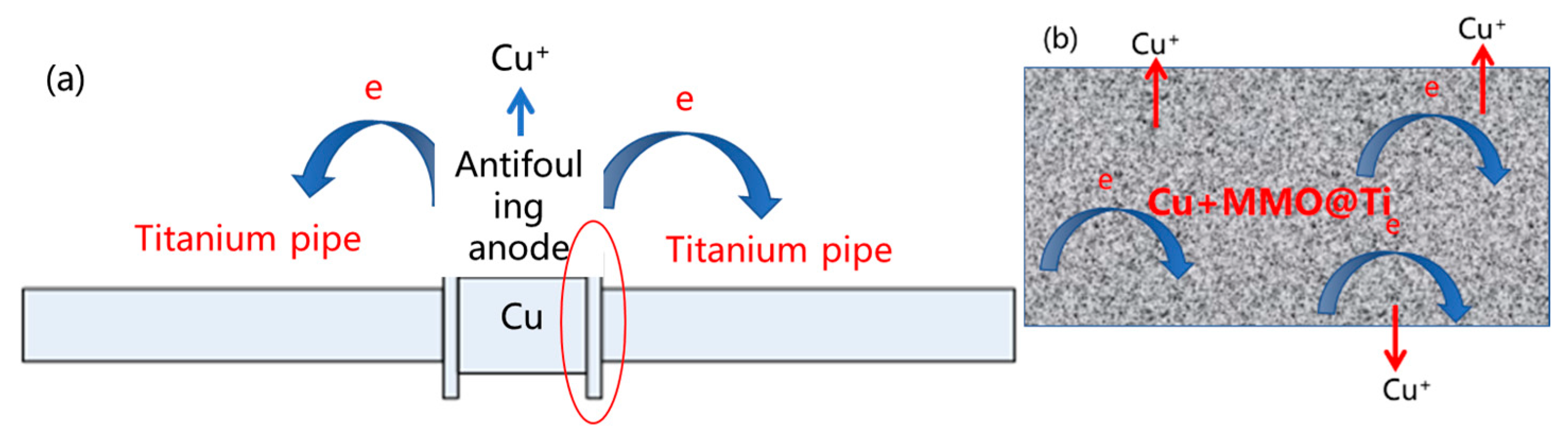

2.1.1. Physical Problem

2.1.2. Geometry Model

2.1.3. State Equations

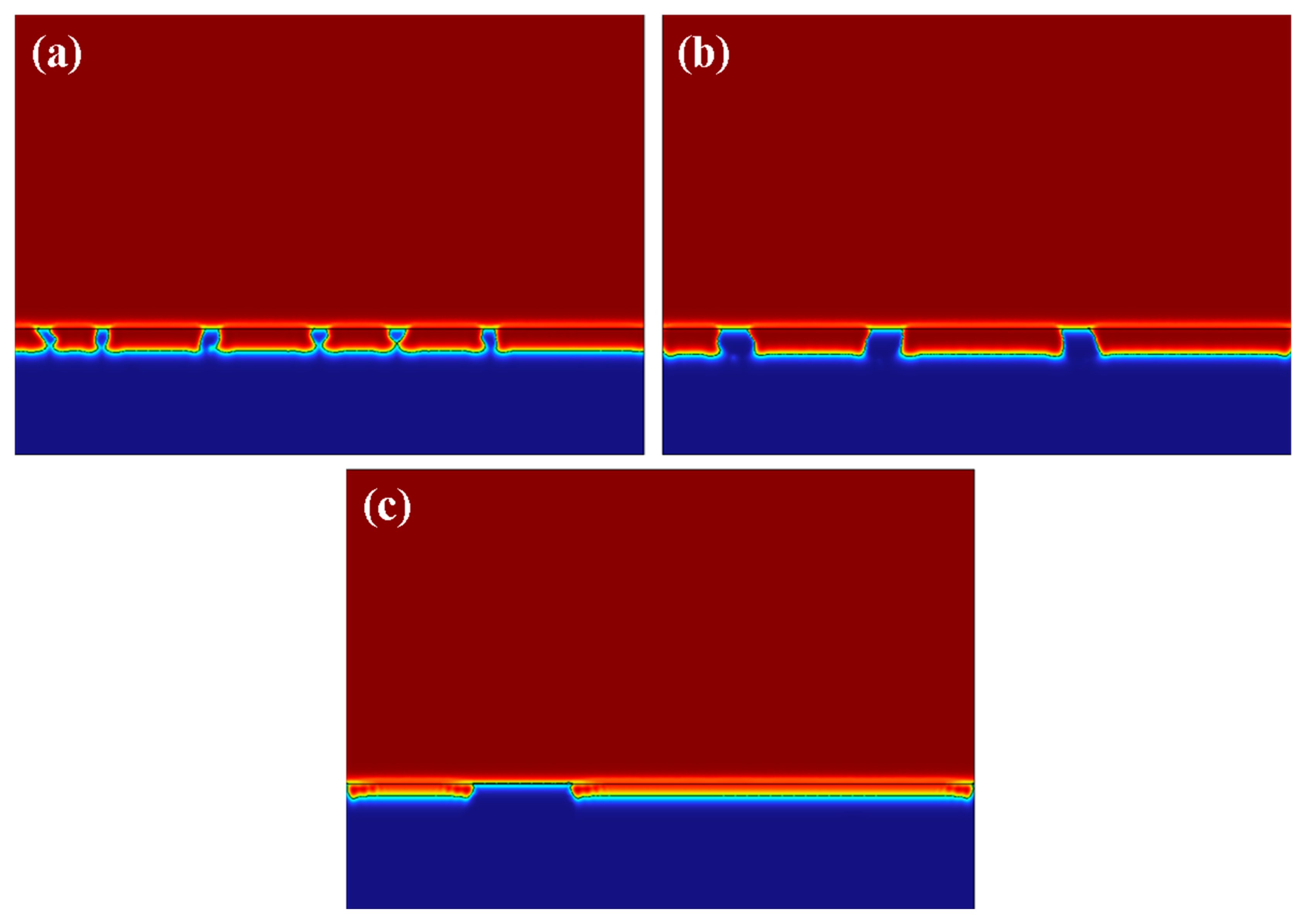

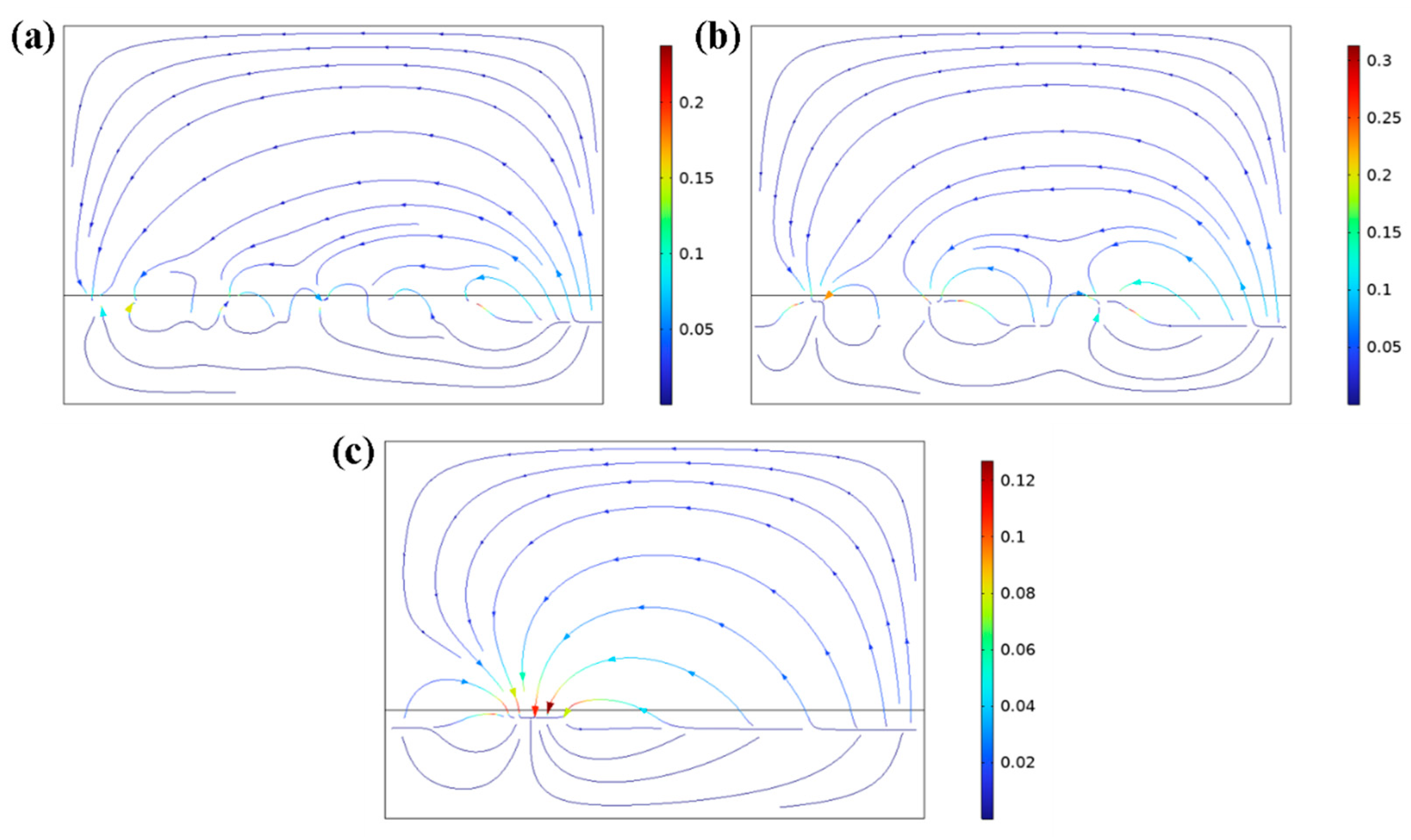

2.1.4. Level Set Method

2.1.5. Boundary Condition Setting

2.2. Cu Ions Releasing Rate Verification

Anode Preparation

2.3. Microstructure Characterization

2.4. Cu Ions Relaeasing Behavior

3. Results

3.1. The Ti Content Influene on the Releasing Current

3.2. The Ti Particle Diameter Influence the Releasing Current

3.3. The Real Corrosion Behavior of Cu-Ti Anode

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.Z.; Jiang, Q.T.; Han, D.X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.P.; Pei, Y.T.; Duan, J.Z.; Hou, B.R. Progress in anti-biofouling materials and coatings for the marine environment. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Liang, H.; Li, Y. Review of Progress in Marine Anti-Fouling Coatings: Manufacturing Techniques and Copper- and Silver-Doped Antifouling Coatings. Coatings 2024, 14, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debiemme-Chouvy, C.; Cachet, H. Electrochemical (pre)treatments to prevent biofouling. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2018, 11, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Feng, K.; Li, J. Marine antifouling strategies: Emerging opportunities for seawater resource utilization. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 149859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, D.; Casanueva, J.F.; Nebot, E. Assessment of the antifouling effect of five different treatment strategies on a seawater cooling system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 85, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Al-Jumaili, A.; Bazaka, O. Functional nanomaterials, synergisms, and biomimicry for environmentally benign marine antifouling technology. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8, 3201–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, H. Progress of marine biofouling and antifouling technologies. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2010, 56, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Tian, L.; Bing, W. Bioinspired marine antifouling coatings: Status, prospects, and future. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 124, 100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X. Special issue on advanced corrosion-resistance materials and emerging applications. The progress on antifouling organic coating: From biocide to biomimetic surface. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.H.; Wang, H.T.; Yu, L. Effect of Zn Content on Electrochemical Properties of Al-Zn-In-Mg Sacrificial Anode Alloy. J. Chin. Soc. Corros. Prot. 2023, 43, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.L. Research progress of biofouling and its control technology in marine underwater facilities. Mar. Sci. 2020, 44, 162–177. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.J. Research of the Chlorine in the Seawater Electrolysis Antifouling System. Master’s Thesis, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.F.; Li, Z.X.; Wang, H.N. Corrosion Behavior of T2 Copper in Static Artificial Seawater. Mater. Prot. 2018, 51, 14–17+52. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Liu, X.J.; Liu, N.Z. Galvanic Corrosion of T2 Cu-alloy and Q235 Steel in Simulated Beishan Groundwater Environment. J. Chin. Soc. Corros. Prot. 2024, 44, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.F.; Li, Z.X.; Wang, H.N. Galvanic corrosion behavior of T2/TC4 galvanic couple in static artificial seawater. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2019, 48, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Xu, K.; Hu, J. Durable self-polishing antifouling Cu-Ti coating by a micron-scale Cu/Ti laminated microstructure design. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 79, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Y.; Cao, C.C.; Yang, X.W. Cold spraying hybrid processing technology and its application. J. Mater. Eng. 2019, 47, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.R.; Li, X.; Liu, C. Principle and application of localized scanning electrochemical measurement technology. Mod. Chem. Res. 2024, 8, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Milagre, M.X.; Donatus, U.; Mogili, N.V. Galvanic and asymmetry effects on the local electrochemical behavior of the 2098-T351 alloy welded by friction stir welding. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 45, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.D.; Lu, J.; Sun, C.C. Progress of the additive manufacturing applications of cold spray technique. Surf. Technol. 2024, 53, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Wang, H.; Li, X. Deposition efficiency of low pressure cold sprayed aluminum coating. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2017, 33, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbaum, D.; Shockley, J.M.; Chromik, R.R. The Effect of Deposition Conditions on Adhesion Strength of Ti and Ti6Al4V Cold Spray Splats. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2011, 21, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.W.; Li, W.Y.; Xing, C.H. Research Progress in Cold Spraying of Copper Coating. Mater. Prot. 2022, 55, 58–70+85. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.J.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhai, H.M. Corrosion behaviors cold spraying Zn-Al composite coating in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution. J. Lanzhou Univ. Technol. 2023, 49, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Yang, F.; Chen, Z. Enhancing mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of nickel-aluminum bronze via hot rolling process. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.B.; Du, X.G.; Wang, Q.W. Corrosion Behavior of Copper in a Simulated Grounding Condition in Electric Power Grid. J. Chin. Soc. Corros. Prot. 2023, 43, 435–440. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Xu, K.; Tian, J. Tailoring the Micro-galvanic Dissolution Behavior and Antifouling Performance Through Laminated-Structured Cu-X Composite Coating. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2021, 30, 1566–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Hu, J.Y.; Qiu, S.W. Analysis on Galvanic Corrosion Behavior of TA2, BAl7-7-2-2 and 921A. Dev. Appl. Mater. 2018, 33, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, L.D.; Sun, W. Effect of corrosion products of pure iron on the corrosion behavior of pure iron and its mechanism. Mater. Prot. 2021, 54, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, R.; Li, X.B.; Wang, J. Study on antifouling effect of cold spray Cu-Cu2O coating. Paint. Coat. Ind. 2013, 43, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Elmas, S.; Skipper, K.; Salehifar, N. Cyclic Copper Uptake and Release from Natural Seawater-A Fully Sustainable Antifouling Technique to Prevent Marine Growth. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.J.; Wang, K.; Xu, K.W. Effect of coating composition on the micro-galvanic dissolution behavior and antifouling performance of plasma-sprayed laminated-structured Cu Ti composite coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 410, 126963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.; Chen, X. Research Progress of Galvanic Corrosion in Marine Environment. J. Chin. Soc. Corros. Prot. 2022, 42, 531–539. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.L.; Zhang, F.; Huang, G.S.; Jiang, D.; Dong, G.J. Corrosion Behavior of Cold Spray Cu-Ti Pseudo Alloy as Anti-fouling Material in Natural Seawater. J. Chin. Soc. Corros. Prot. 2025, 45, 1310–1321. [Google Scholar]

| Physical Variable | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| σ | 4 S/m | Conductivity of seawater |

| M_Cu | 63.55 g/mol | Molecular mass of Cu |

| rho_Cu | 8940 kg/m3 | Density of Cu |

| n | 2 | Charge transfer numbers |

| Expression | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|

| (i_alpha(-phil)*(1 − micro(x,y)) + i_beta(-phil)*micro(x,y)) (y <= 0) | A/m2 | Local current density |

| (1/2)*i_loc/F_const*(1 − micro(x,y)) | mol/(m2·s) | Corrosion rate |

| Rc*M/rho*(1 − micro(x,y)) | m/s | Releasing rate |

| Sigma*ls.Vf1 + 0.1[S/m]*ls.Vf2 | S/m | Conductivity |

| Temperature (℃) | 900.0 |

| Pressure (MPa) | 5.5 |

| Temperature (℃) | 750 |

| Stand-off distance (mm) | 25.0 |

| Process gas | N2 |

| Powder feeding rate/(g·min−1) | 40.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, Y.; Cai, F.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, H.; Qian, J.; Ma, L.; Huang, G. The Cu Ions Releasing Behavior of Cu-Ti Pseudo Alloy Antifouling Anode Deposited by Cold Spray in Marine Environment. Coatings 2025, 15, 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121433

Su Y, Cai F, Wang Y, Wu S, Wang H, Qian J, Ma L, Huang G. The Cu Ions Releasing Behavior of Cu-Ti Pseudo Alloy Antifouling Anode Deposited by Cold Spray in Marine Environment. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121433

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Yan, Fulei Cai, Yuhao Wang, Shuai Wu, Hongren Wang, Jiancai Qian, Li Ma, and Guosheng Huang. 2025. "The Cu Ions Releasing Behavior of Cu-Ti Pseudo Alloy Antifouling Anode Deposited by Cold Spray in Marine Environment" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121433

APA StyleSu, Y., Cai, F., Wang, Y., Wu, S., Wang, H., Qian, J., Ma, L., & Huang, G. (2025). The Cu Ions Releasing Behavior of Cu-Ti Pseudo Alloy Antifouling Anode Deposited by Cold Spray in Marine Environment. Coatings, 15(12), 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121433