Carbon Microfibers Coated with 3-Methyl-4-Phenylpyrrole for Possible Uses in Energy Storage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials, Technology and Characterization Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Technology

2.3. Characterization Equipment

3. Results and Discussion

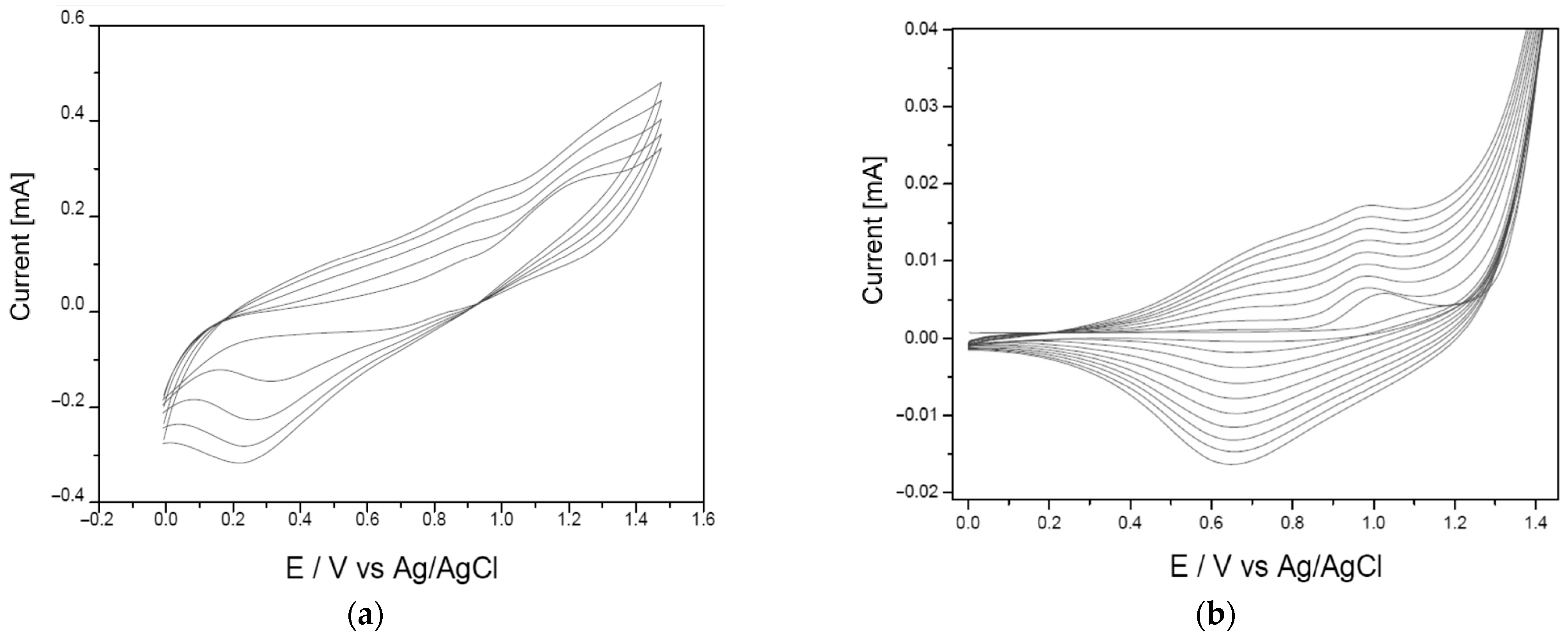

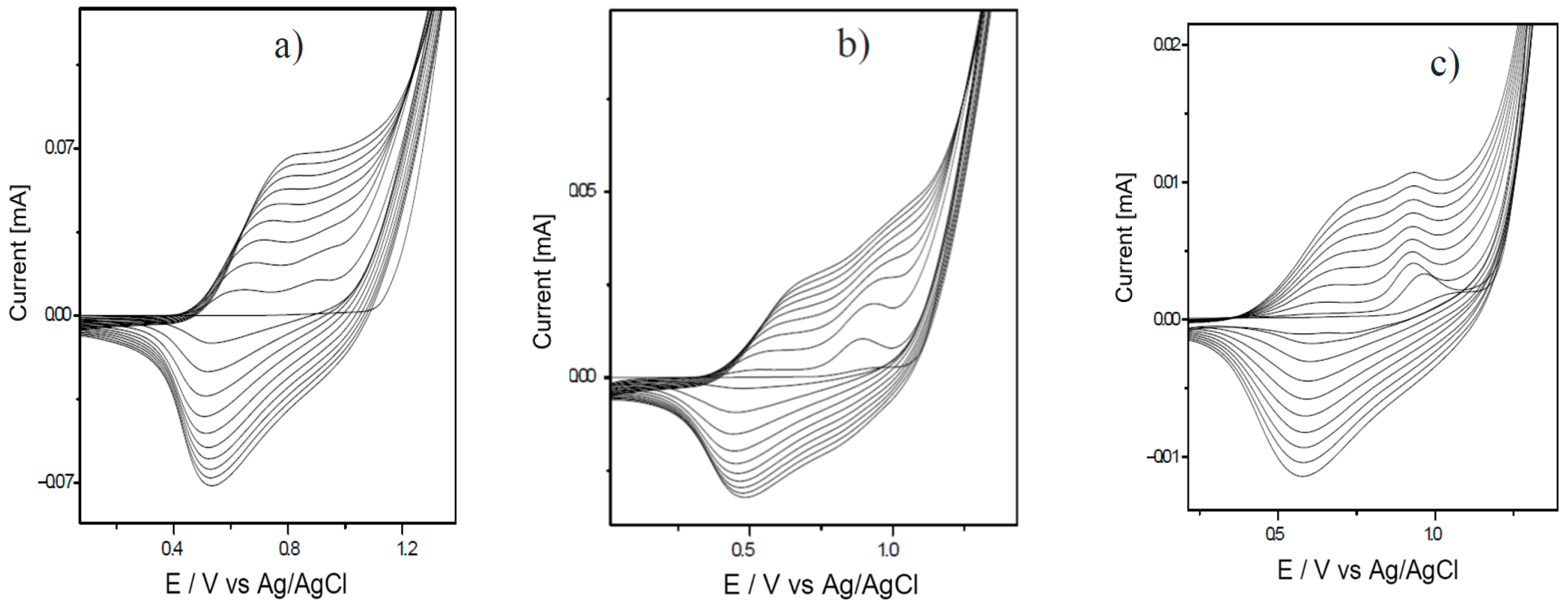

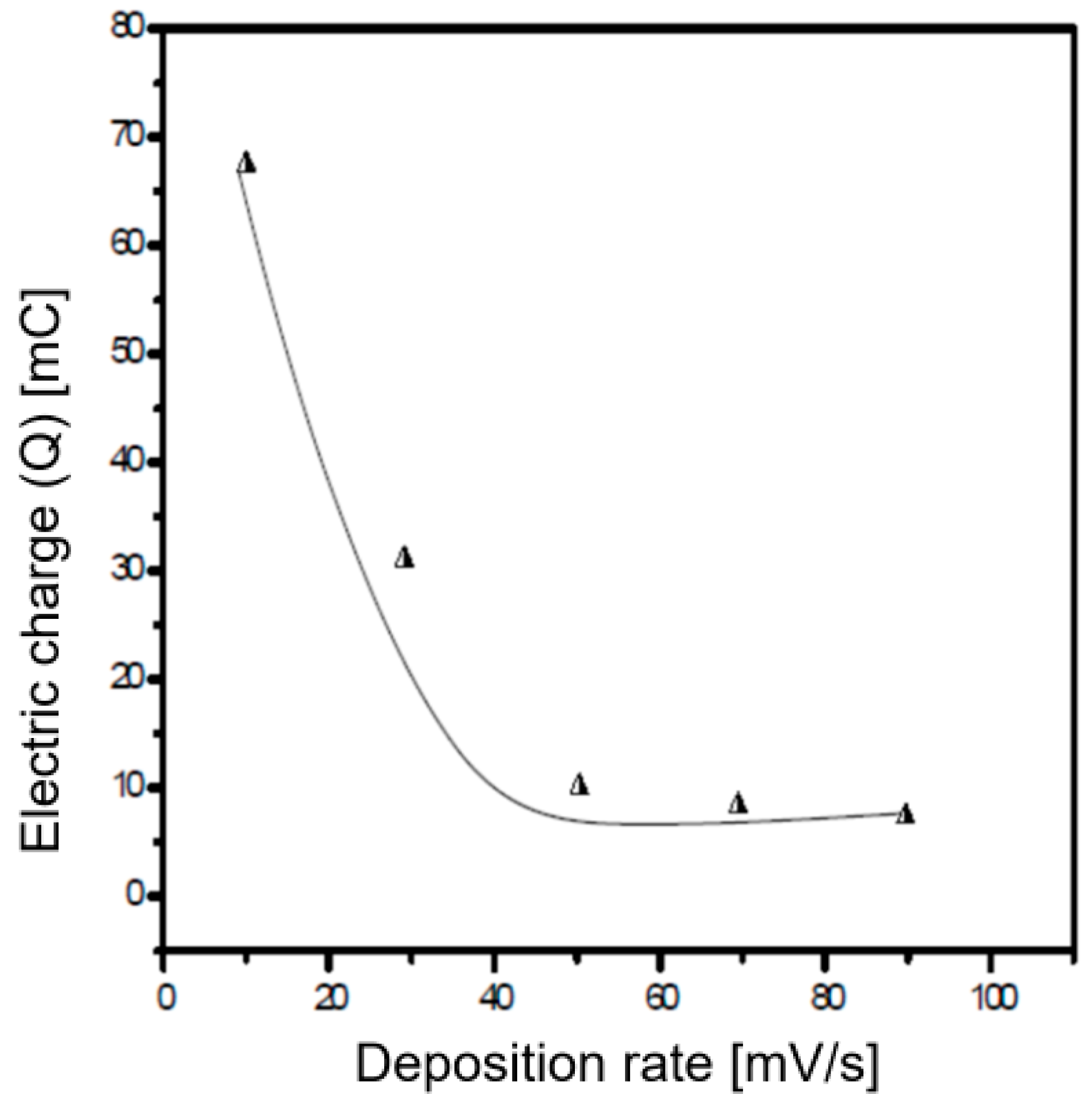

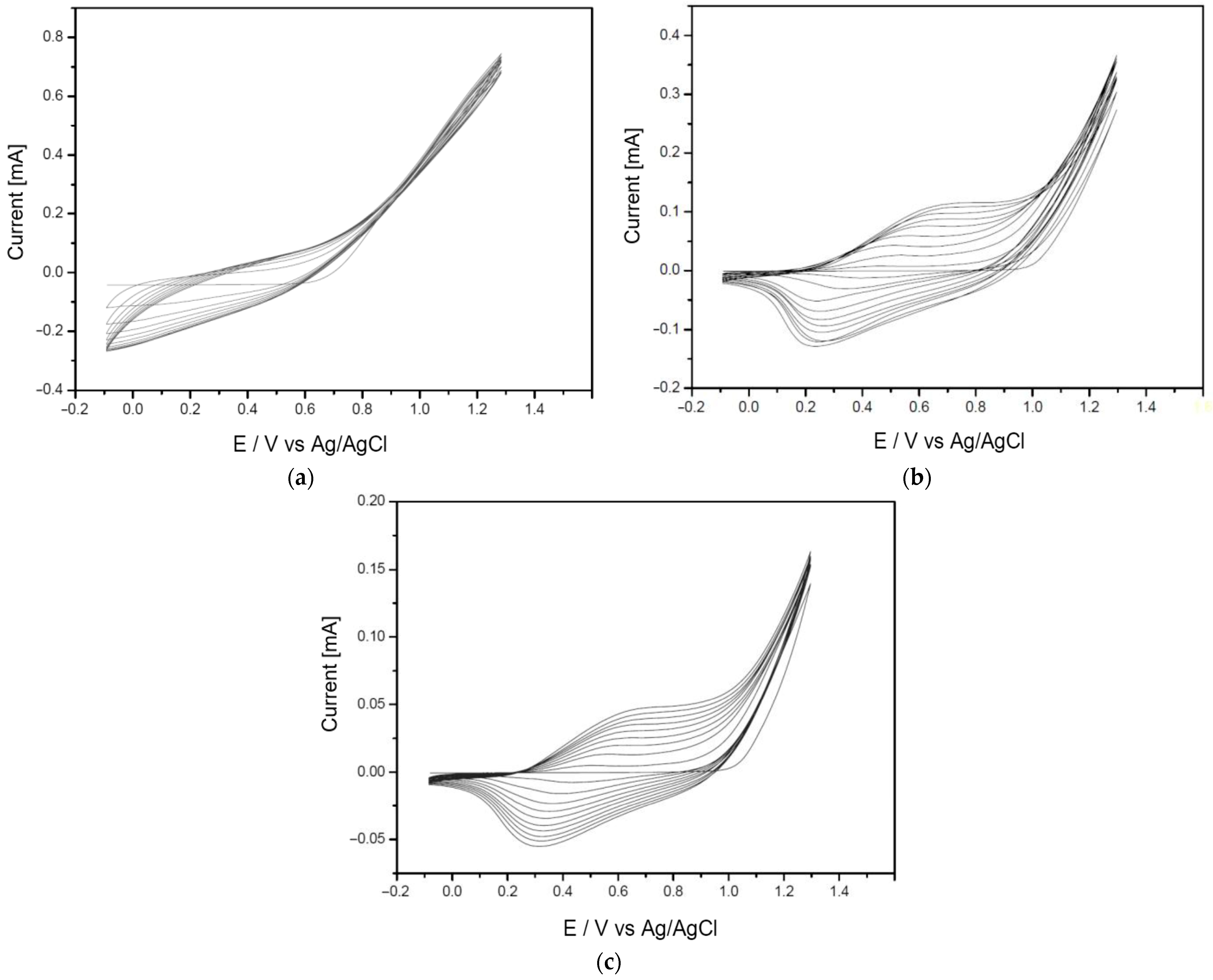

3.1. Analysis of the Polymer Deposition Process

3.2. Structural Analysis

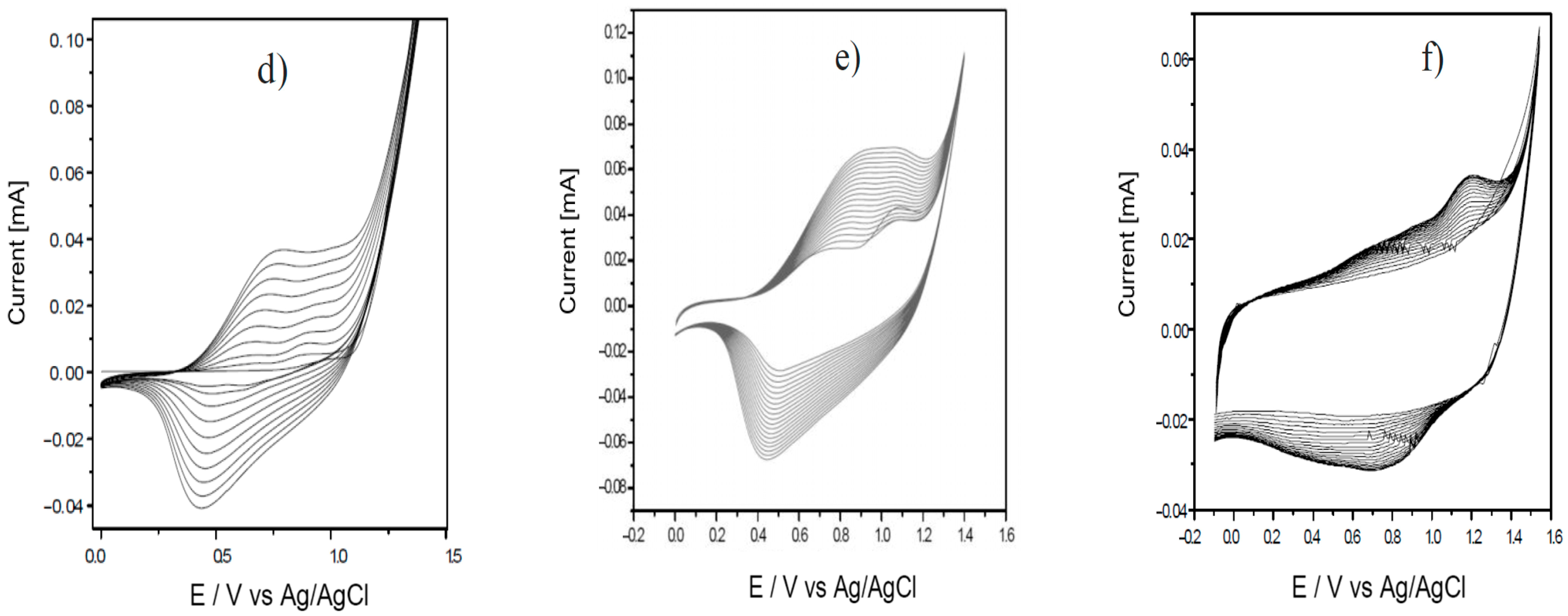

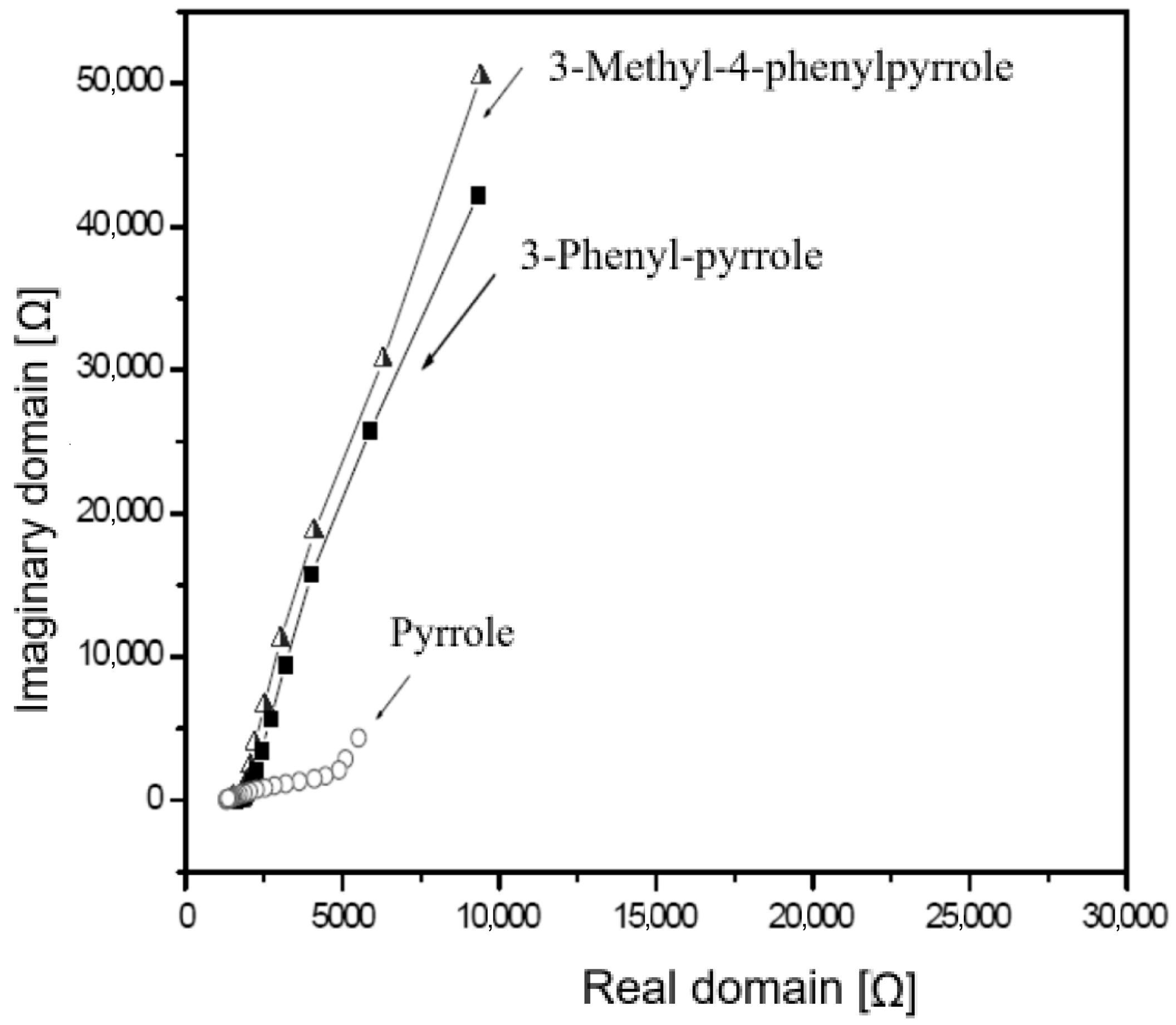

3.3. Comparative Analysis of the Activity Versus Carbon Micro-Fibers After Electrochemical Polymerization of PPy, 3-Methyl-Pyrrole and 3-Methyl-4-Phenylpyrrole Polymers

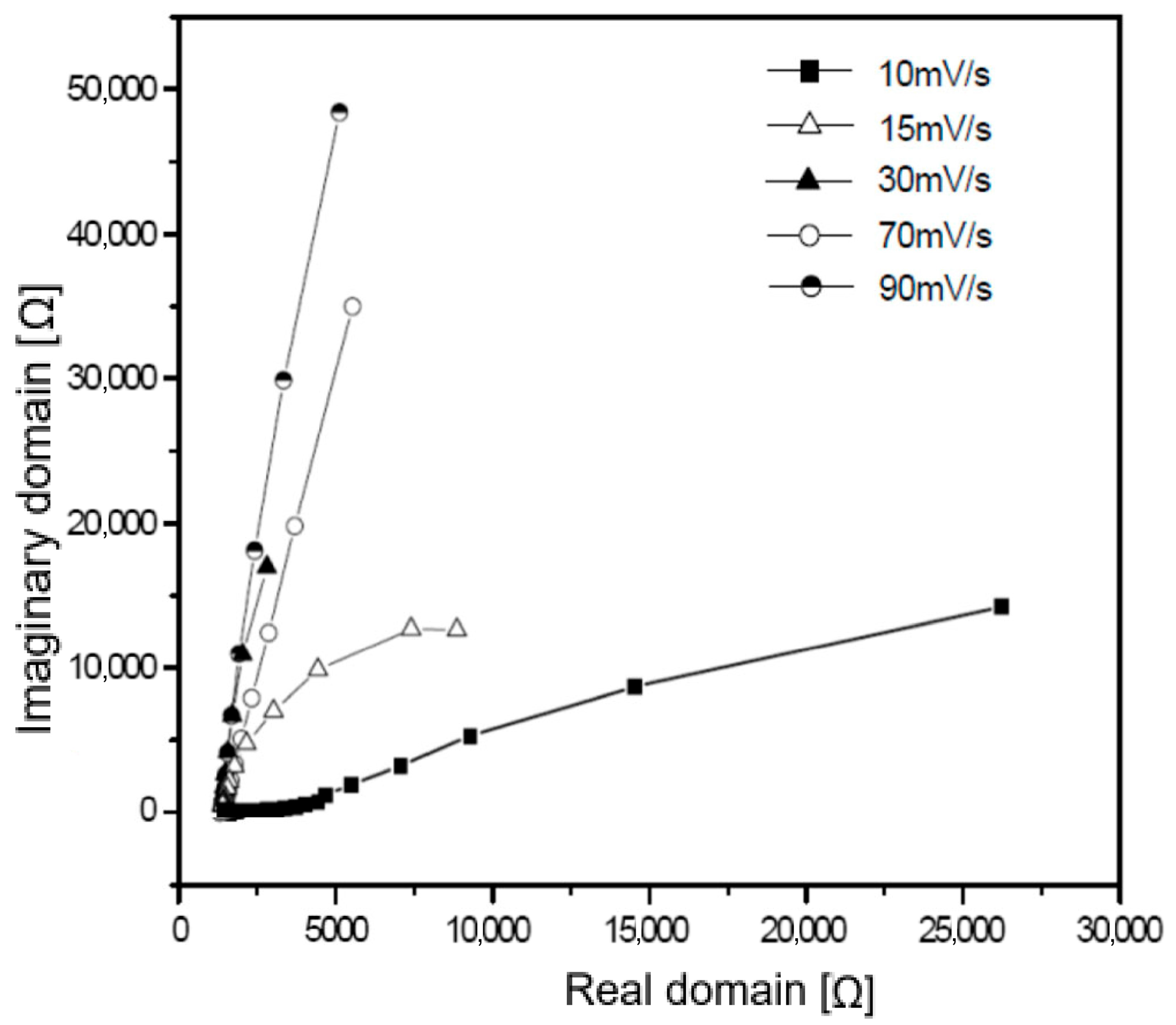

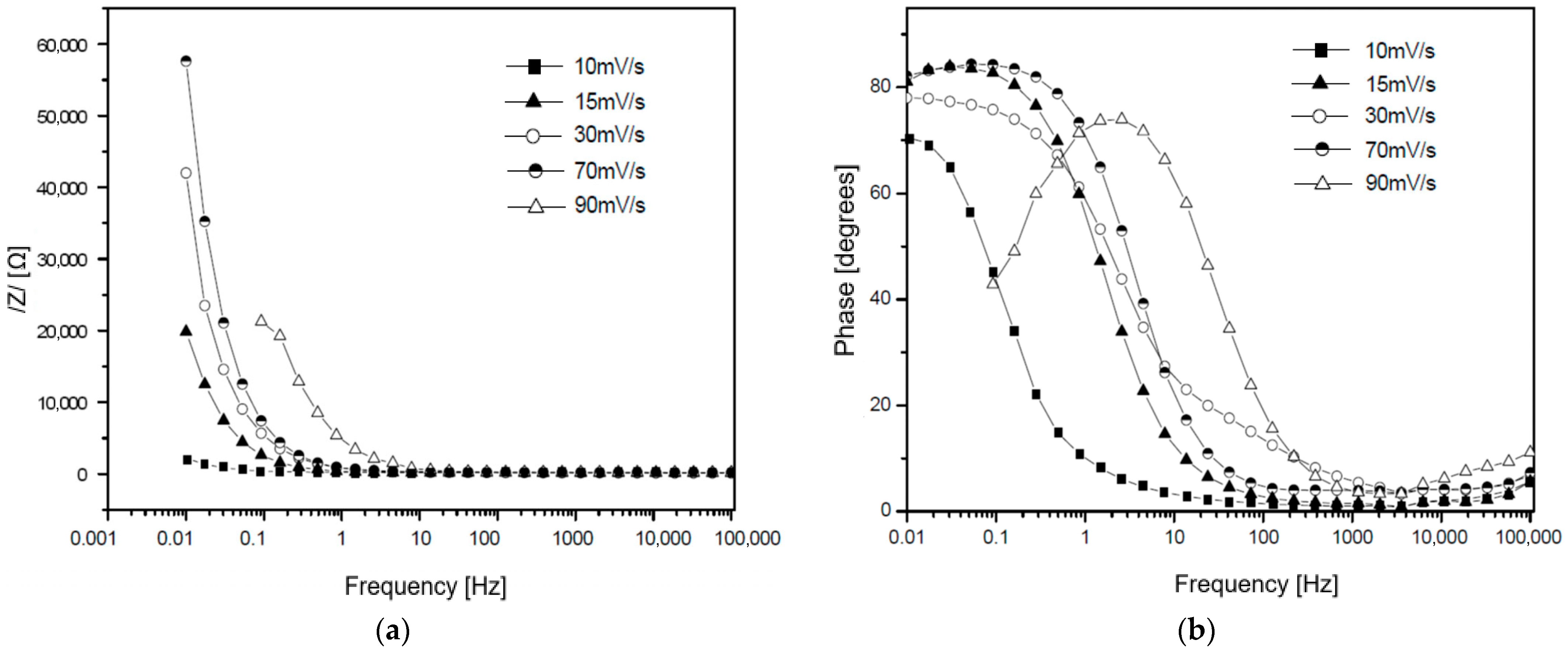

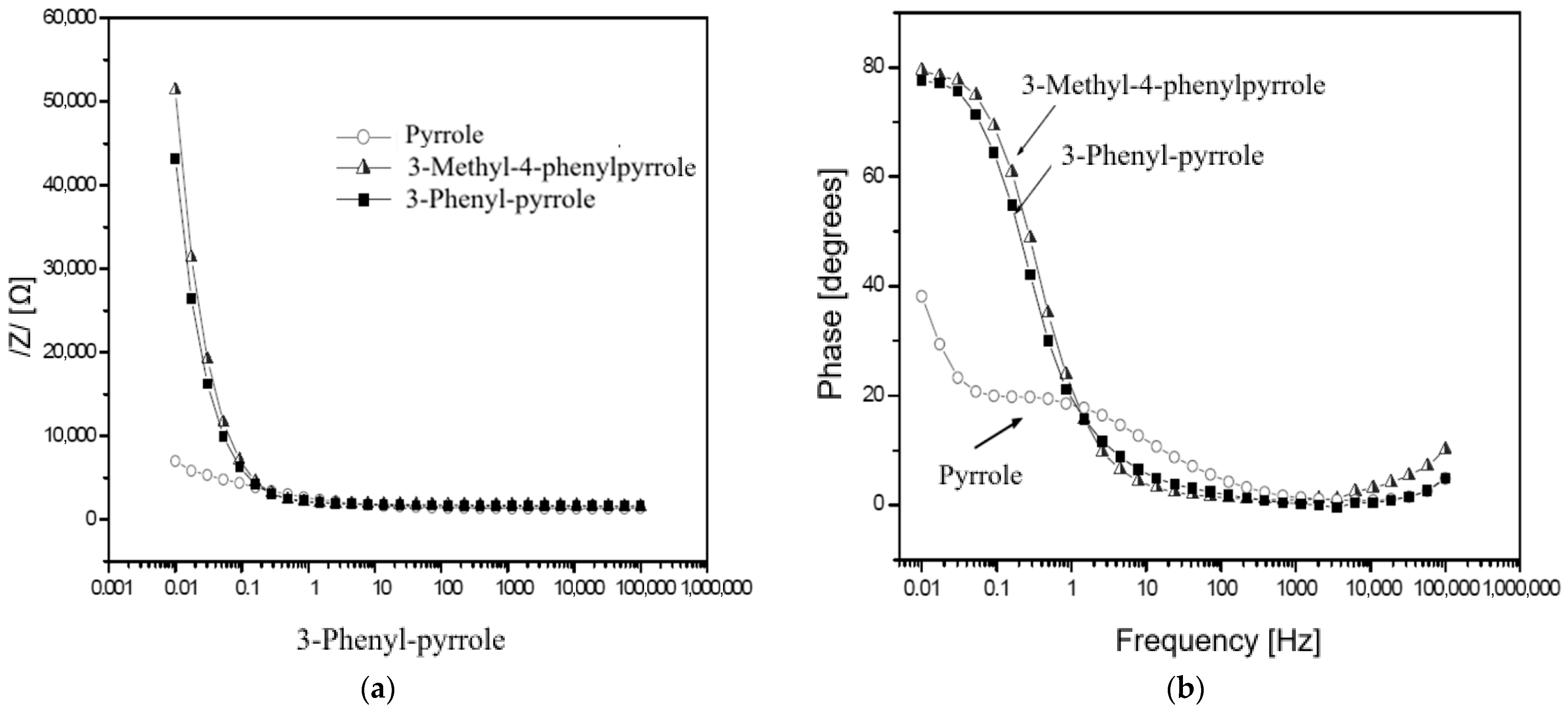

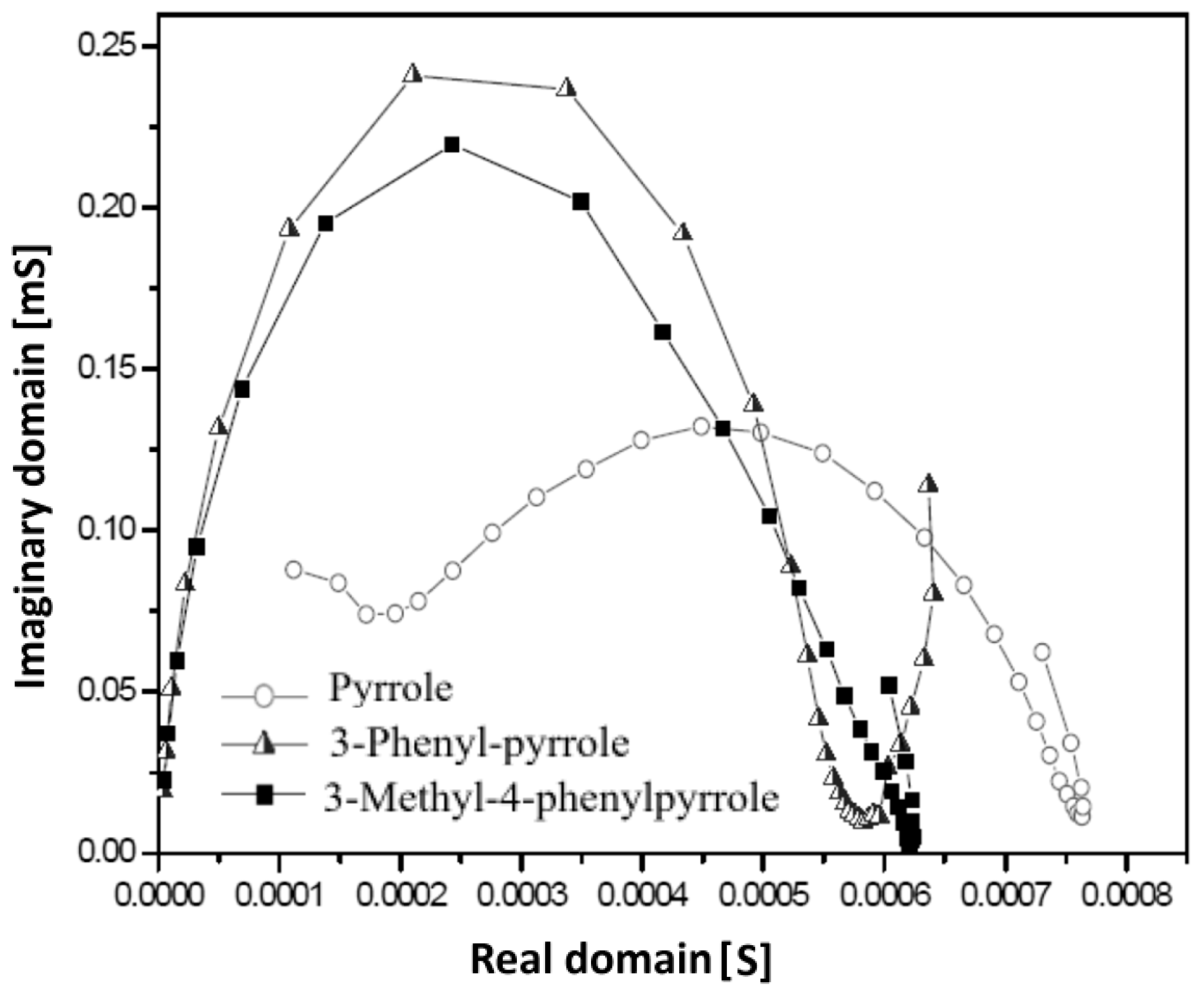

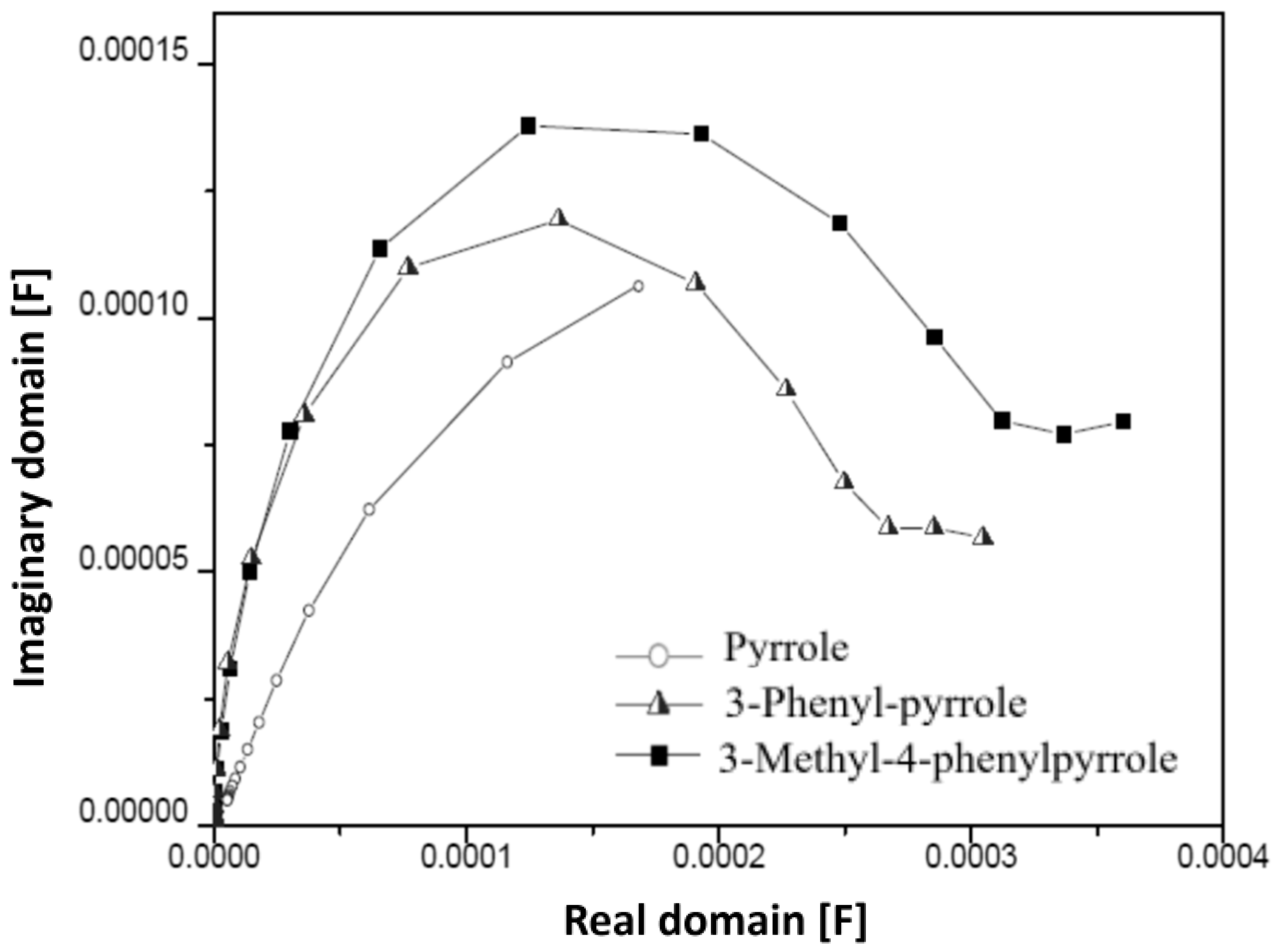

3.4. Electrochemical Impedance Analysis

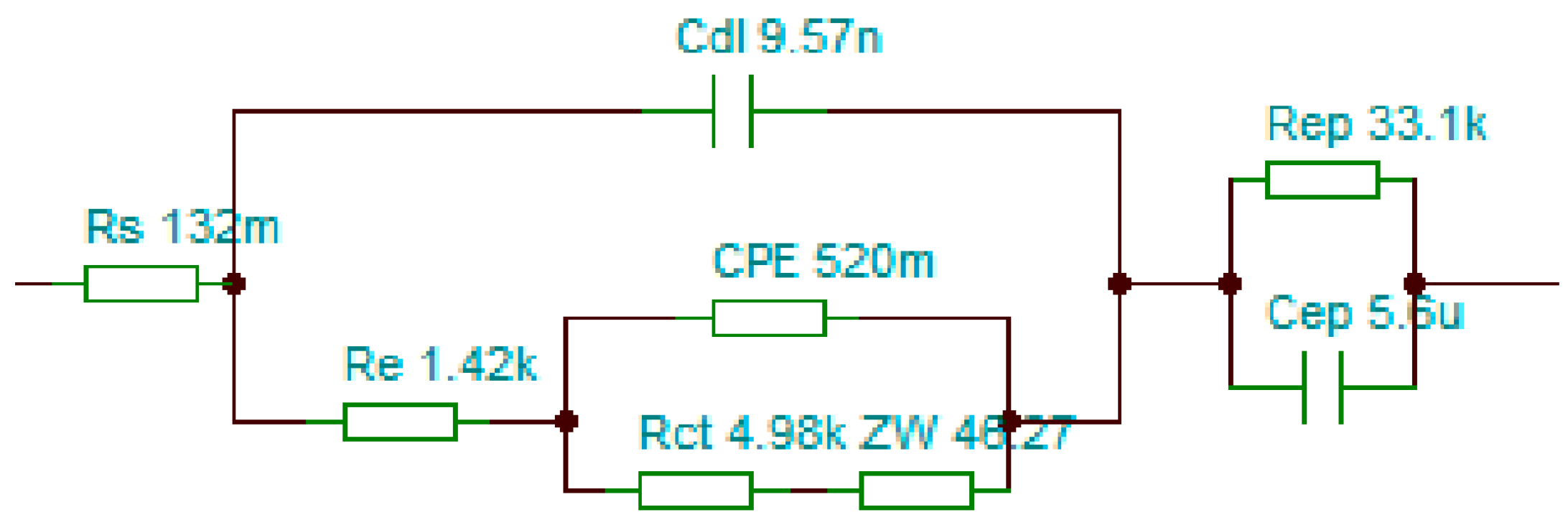

3.5. Equivalent Circuit Modeling Based on Electrochemical Impedance Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hao, L.; Dong, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, K.; Yu, D. Polypyrrole nanomaterials: Structure, preparation and application. Polymers 2022, 14, 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Jadoon, S.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Hegazy, H.H.; Ahmad, Z.; Yahia, I.S. Recent progress in polypyrrole and its composites with carbon, metal oxides, sulfides and other conducting polymers as an emerging electrode material for asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2024, 85, 110955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Dong, C.; Yu, D. Polypyrrole Derivatives: Preparation, Properties and Application. Polymers 2024, 16, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul, N.S.; Han, J.I. Polypyrrole nanostructures//activated carbon based electrode for energy storage applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 7890–7900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.; Tapadia, K.; Maharana, T. Casting of carbon cloth enrobed polypyrrole electrode for high electrochemical performances. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andezai, A.; Iroh, J. Sustainable Energy Storage Systems: Polypyrrole-Filled Polyimide-Modified Carbon Nanotube Sheets with Remarkable Energy Density. Energies 2025, 18, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, D.; Liu, X.; Du, X.; Li, S.; Xing, X.; Cheng, X.; Bi, D.; Qiu, D. Facile Synthesis of Novel Conducting Copolymers Based on N-Furfuryl Pyrrole and 3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene with Enhanced Optoelectrochemical Performances Towards Electrochromic Application. Molecules 2025, 30, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouris, C.; Crayston, J.; Walton, J. Poly(N-hydroxypyrrole) and poly(3-phenyl-N-hydroxypyrrole): Synthesis, conductivity, spectral properties and oxidation. Synth. Met. 1992, 48, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, K.B. Fabrication and electrochemical properties of carbon nanotube/polypyrrole composite film electrodes with controlled pore size. J. Power Sources 2008, 176, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, F.; Cai, Y.; Yang, P. Electrodeposition of Graphene/Polypyrrole Electrode for Flexible Supercapacitor with Large Areal Capacitance. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 5832–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wu, Q.; Lu, Y. Recent Progress of the Application of Electropolymerization in Batteries and Supercapacitors: Specific Design of Functions in Electrodes. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202300776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Füser, M.; Bolte, M.; Terfort, A. Self-assembled monolayers of aromatic pyrrole derivatives: Electropolymerization and electrocopolymerization with pyrrole. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 246, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Yue, G.; Guo, S. Porous polypyrrole-derived carbon nanotubes as a cathode material for zinc-ion hybrid supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 108925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Du, X.; Wang, J.; Ma, H.; Jing, X. Polypyrrole composites with carbon materials for supercapacitors. Chem. Pap. 2017, 71, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zheng, L.; Wang, X.; Yi, L.; Zhang, X. Polypyrrole/carbon aerogel composite materials for supercapacitor. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 6964–6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhitomirsky, I. Influence of dopants and carbon nanotubes on polypyrrole electropolymerization and capacitive behavior. Mater. Lett. 2013, 98, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoglio, R.A.; Biaggio, S.R.; Bocchi, N.; Rocha-Filho, R.C. Flexible and high surface area composites of carbon fiber, polypyrrole, and poly(DMcT) for supercapacitor electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 93, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, A.; Rahman, M.; Hossain, T.; Hossain, I.; Sheikh, S.; Rahman, S.; Uddin, N.; Donne, S.W.; Hoque, I.U. Advances in Conductive Polymer-Based Flexible Electronics for Multifunctional Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Paul, R.; Da, L. Carbon-based supercapacitors for efficient energy storage. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017, 4, 453–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, J.; Manikandan, R.; Lee, W.-G.; Cho, W.-J.; Yu, K.H.; Kim, B.C. Polypyrrole thin film on electrochemically modified graphite surface for mechanically stable and high-performance supercapacitor electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 283, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.K.; Lim, Y.S.; Pandikumar, A.; Huang, N.M.; Lim, H.N. Graphene/polypyrrole-coated carbon nanofiber core–shell architecture electrode for electrochemical capacitors. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 12692–12699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, C.J.; Kim, B.C.; Cho, W.J.; Lee, W.G.; Jung, S.D.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, S.Y.; Yu, K.H. Highly flexible and planar supercapacitors using graphite flakes/polypyrrole in polymer lapping film. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 13405–13414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Flournoy, R.C.; Torres, J.A.; Snelling, R.R.; Spande, T.F.; Garraffo, H.M. 3-Methyl-4-phenylpyrrole from the Ants Anochetus kempfi and Anochetus mayri. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1343–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, F.; Rückle, D.; Killian, M.; Turhan, M.; Virtanen, S. Electropolymerization and Characterization of Poly-N-methylpyrrole Coatings on AZ91D Magnesium Alloy. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 11924–11932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, B.; Bereket, G. Cyclic Voltammetric Synthesis of Poly(N-methyl pyrrole) on Copper and Effects of Polymerization Parameters on Corrosion Performance. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 5246–5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, T.; Ledwon, P. Electrochemically Produced Copolymers of Pyrrole and Its Derivatives: A Plentitude of Material Properties Using “Simple” Heterocyclic Co-Monomers”. Materials 2021, 14, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarac, A.S.; Sezgin, S.; Ates, M.; Turhan, C.M.; Parlak, E.A.; Irfanoglu, B. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of poly(N-methyl pyrrole) on carbon fiber microelectrodes and morphology. Prog. Org. Coat. 2008, 62, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, M.; Sarac, A.S.; Gencturk, A.; Gilsing, H.D.; Faltz, H.; Schulz, B. Electrochemical impedance characterization and potential dependence of poly[3,4-(2,2-dibutylpropylenedioxy)thiophene] nanostructures on single carbon fiber microelectrode. Synth. Met. 2012, 162, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surface Roughness Parameters. Available online: https://www.keyence.eu/ss/products/microscope/roughness/line/tab03_b.jsp (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- ISO 21920-2:2021; (Previously ISO 4287:1997). Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Profile. Part 2: Terms, Definitions and Surface Texture Parameters. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/72226.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Sarac, A.S.; Ates, M.; Kilic, B. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopic Study of Polyaniline on Platinum, Glassy Carbon and Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2008, 3, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabali, A.; Alkaraki, A.; Gammoh, O.; Qnais, E.; Alqudah, A.; Mishra, V.; Mishra, Y.; El-Tanani, M. Design, structure, and application of conductive polymer hybrid materials: A comprehensive review of classification, fabrication, and multifunctionality. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 27493–27523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, Y.; Singh, K.; Mudila, H.; Lokhande, P.E.; Singh, L.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, A.; Mubarak, N.M.; Dehghani, M.H. Insights into properties, synthesis and emerging applications of polypyrrole-based composites, and future prospective: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazanas, A.; Prodromidis, M. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy—A Tutorial. ACS Meas. Sci. 2023, 3, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randviir, E.; Banks, C. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy: An overview of bioanalytical applications. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 1098–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magar, H.; Hassan, R.; Mulchandani, A. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Principles, Construction, and Biosensing Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X. Recent research progress of conductive polymer-based supercapacitor electrode materials. Text. Res. J. 2023, 93, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Boussoualem, M.; Roussel, F. Spectroscopic and electrical properties of 3-alkyl pyrrole–pyrrole copolymers. Polymer 2007, 48, 4047–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okner, R.; Domb, A.J.; Mandler, D. Electrochemical Formation and Characterization of Copolymers Based on N-Pyrrole Derivatives. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 2928–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gocki, M.; Nowak, A.J.; Karoń, K. Analysis of the parameters, of supercapacitors containing, polypyrrole and its derivatives. Arch. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 120, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mini-Electrode Type | EpA [V] | EpC [V] | ΔE [V] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum | 1.15 | 0.27 | 0.88 |

| Carbon | 1.12 | 0.66 | 0.46 |

| Polymer Deposition Rate [mV/s] | EpA [V] | EpC [V] | ΔE [V] | Q [mC] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 0.81 | 0.49 | 0.32 | 67.59 |

| 30 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 33.86 |

| 70 | 0.89 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 10.13 |

| 90 | 0.81 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 7.78 |

| 500 | 1.06 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 3.41 |

| 1000 | 1.22 | 0.78 | 0.44 | 1.56 |

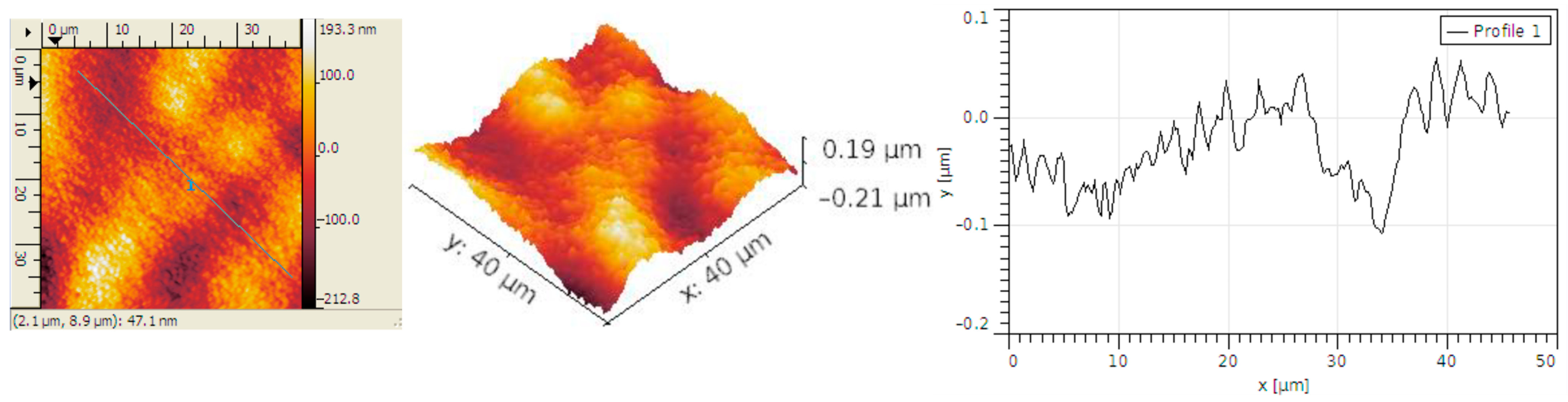

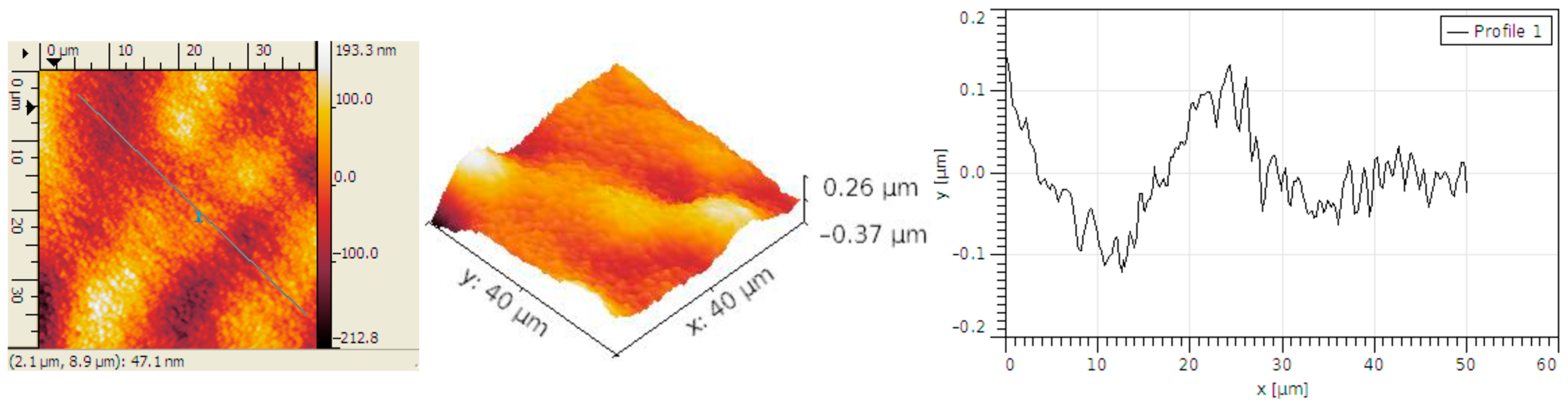

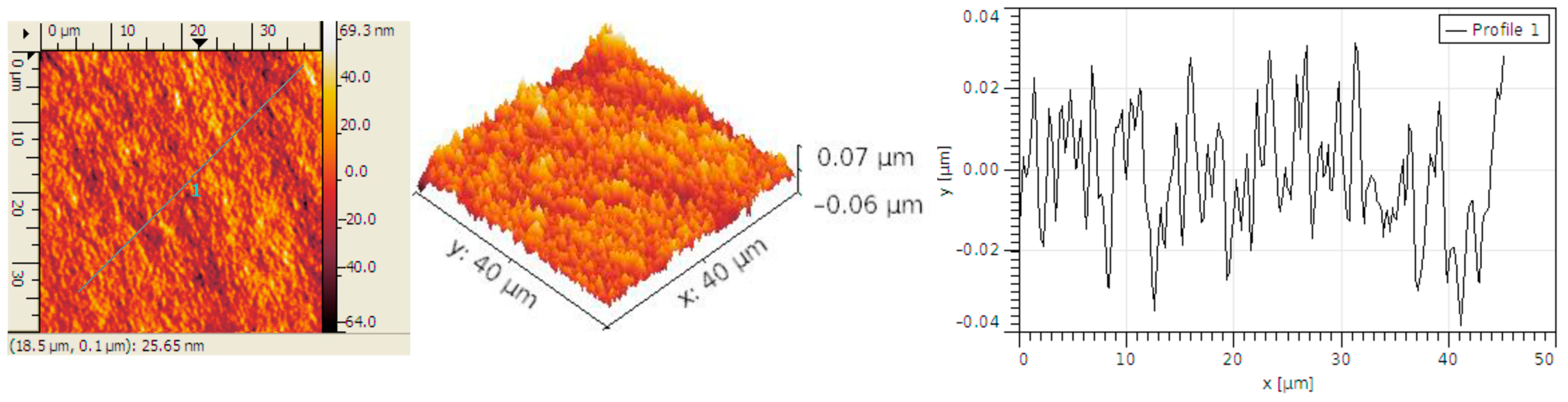

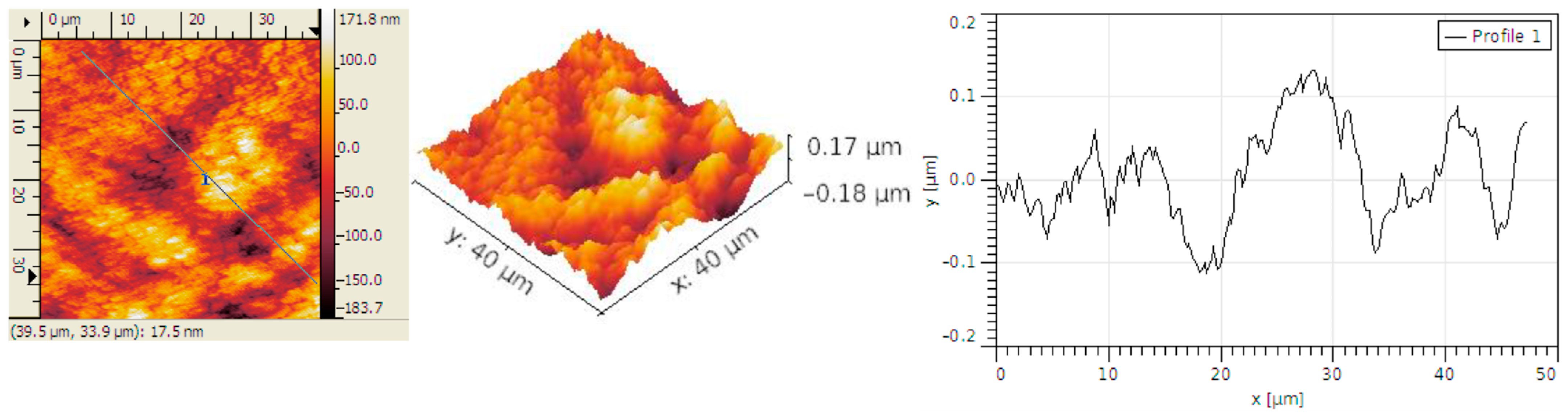

| Sample | RMS (nm) | Ra (nm) | RSk | RKu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon micro-fiber | 62 | 49 | 0.01 | 2.86 |

| Carbon micro-fiber coated at 30 mV/s rate | 70 | 53 | 0.26 | 4.2 |

| Carbon micro-fiber coated at 70 mV/s rate | 15 | 12 | 0.12 | 3.19 |

| Carbon micro-fiber coated at 90 mV/s rate | 58 | 47 | 0.02 | 2.7 |

| Polymer Type | Pyrrole | 3-Phenyl-Pyrrole | 3-Methyl-4-Phenylpyrrole |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q [mC] | 47.51 | 38.43 | 33.84 |

| EpA [V] | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.65 |

| EpC [V] | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

| ΔE [V] | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.33 |

| /Ipa/Ipc/ | 1.27 | 0.95 | 1.02 |

| Polymer Type | Pyrrole | 3-Phenyl-Pyrrole | 3-Methyl-4-Phenylpyrrole |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y [mS] | 0.129 | 0.237 | 0.218 |

| C [F] × 10−4 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.4 |

| Increase of Csp | 0 | +9.1% | +27.3% |

| Specific Parameters | Pyrrole | 3-Phenyl-Pyrrole | 3-Methyl-4-Phenylpyrrole |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rs [Ω] | 0.132 | 1.012 | 1.205 |

| Cdl [μF] | 9.57 × 10−3 | 4.72 × 10−4 | 8.12 × 10−4 |

| Re [Ω] | 1421 | 1284 | 1589 |

| CPE | 0.520 | 0.925 | 0.411 |

| Rct [Ω] | 4987 | 839 | 532 |

| ZW | 46.27 | 852 | 296 |

| Cep [nF] | 5.6 × 103 | 3.48 × 10−4 | 4.43 × 10−4 |

| Rep [Ω] | 3.31 × 103 | 0.21 | 0.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trandabat, A.F.; Ciobanu, R.C.; Schreiner, O.D. Carbon Microfibers Coated with 3-Methyl-4-Phenylpyrrole for Possible Uses in Energy Storage. Coatings 2025, 15, 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121420

Trandabat AF, Ciobanu RC, Schreiner OD. Carbon Microfibers Coated with 3-Methyl-4-Phenylpyrrole for Possible Uses in Energy Storage. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121420

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrandabat, Alexandru Florentin, Romeo Cristian Ciobanu, and Oliver Daniel Schreiner. 2025. "Carbon Microfibers Coated with 3-Methyl-4-Phenylpyrrole for Possible Uses in Energy Storage" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121420

APA StyleTrandabat, A. F., Ciobanu, R. C., & Schreiner, O. D. (2025). Carbon Microfibers Coated with 3-Methyl-4-Phenylpyrrole for Possible Uses in Energy Storage. Coatings, 15(12), 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121420