Microstructure, Elevated-Temperature Tribological Properties and Electrochemical Behavior of HVOF-Sprayed Composite Coatings with Varied NiCr/Cr3C2 Ratios and CoCrFeNiMo Additions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

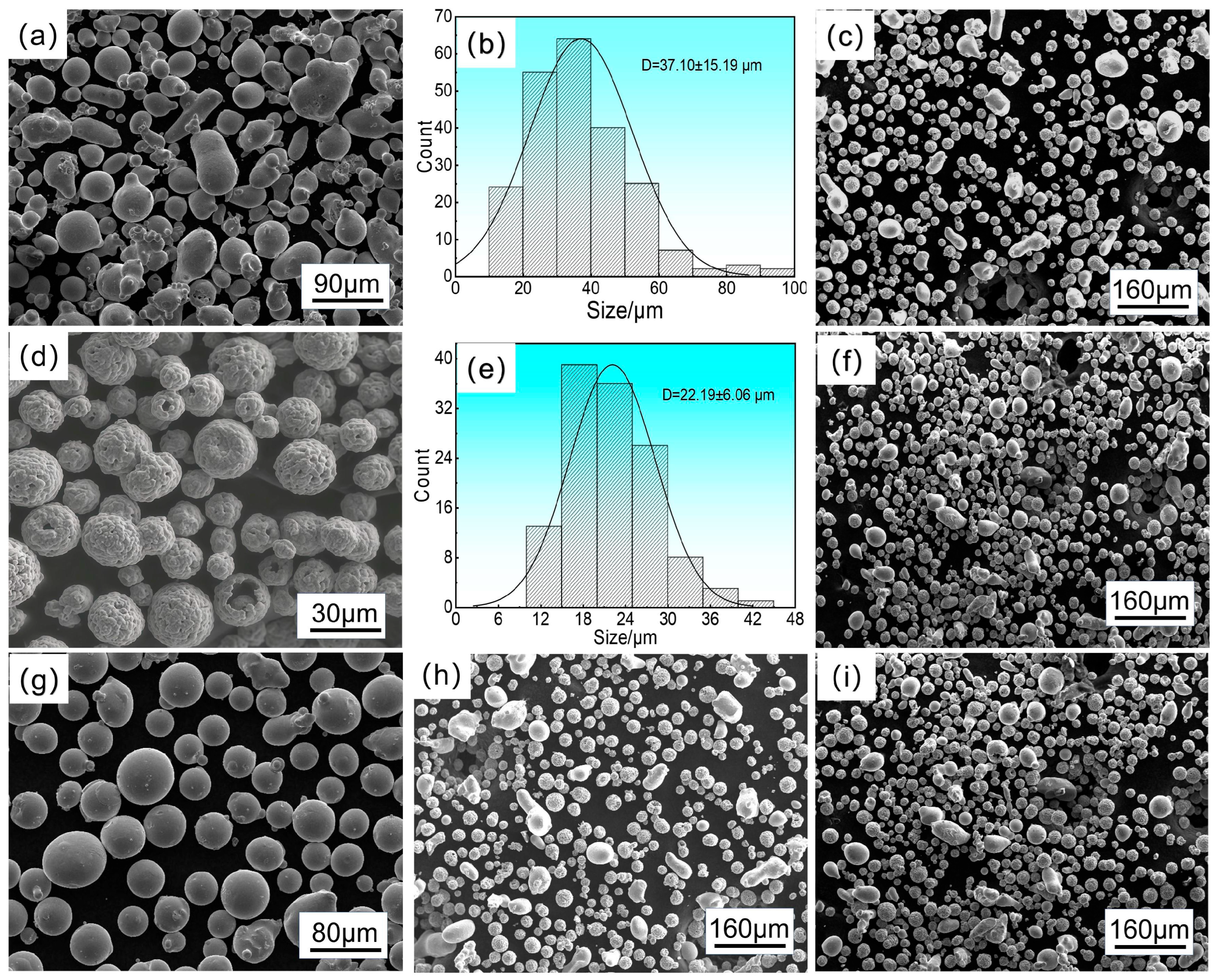

2.1. Powder Raw Materials and Mixing Preparation

2.2. Preparation of Coatings

2.3. Friction and Wear Test

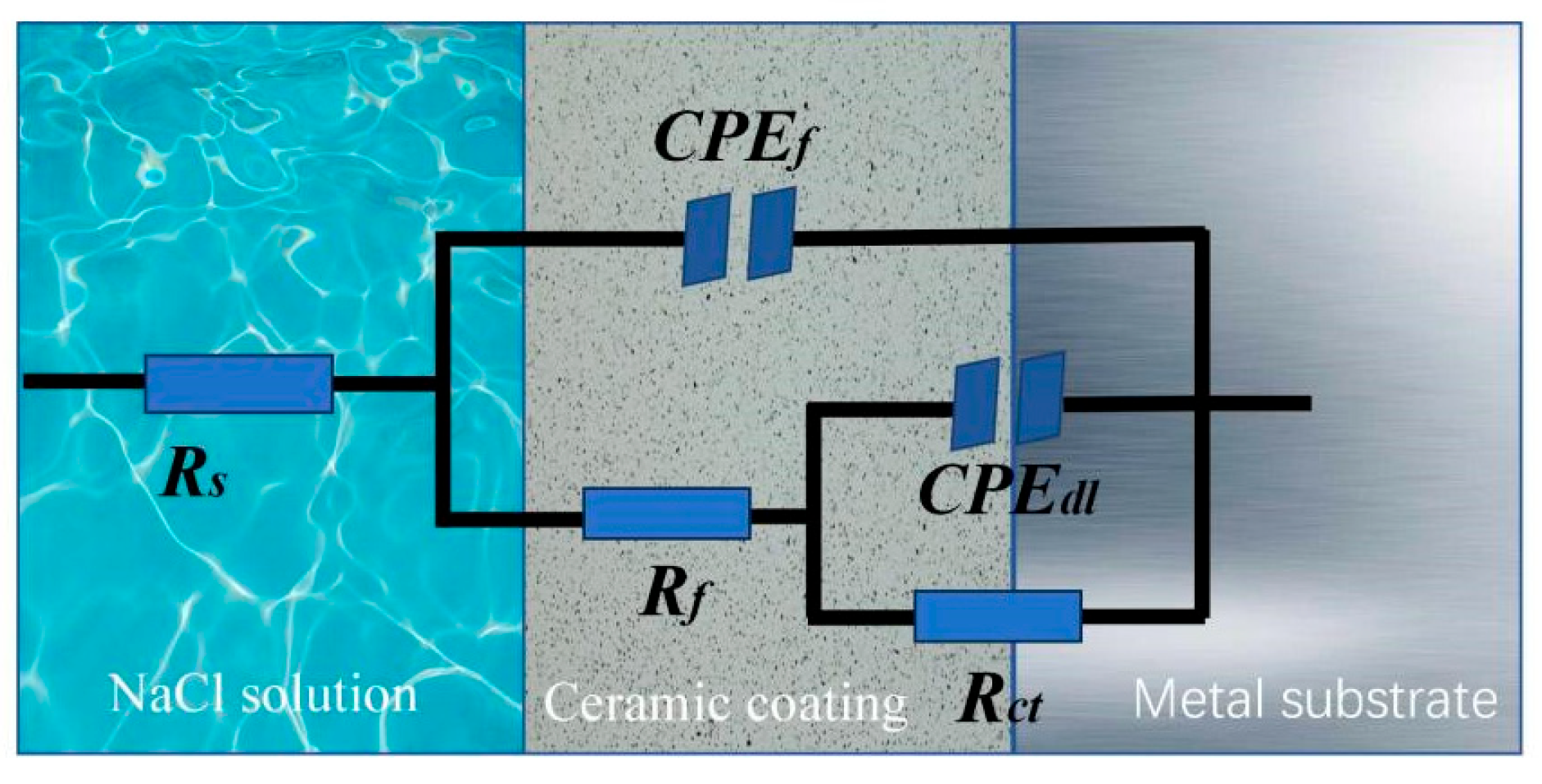

2.4. Electrochemical Tests

2.5. Characterization Method

3. Analysis and Discussion

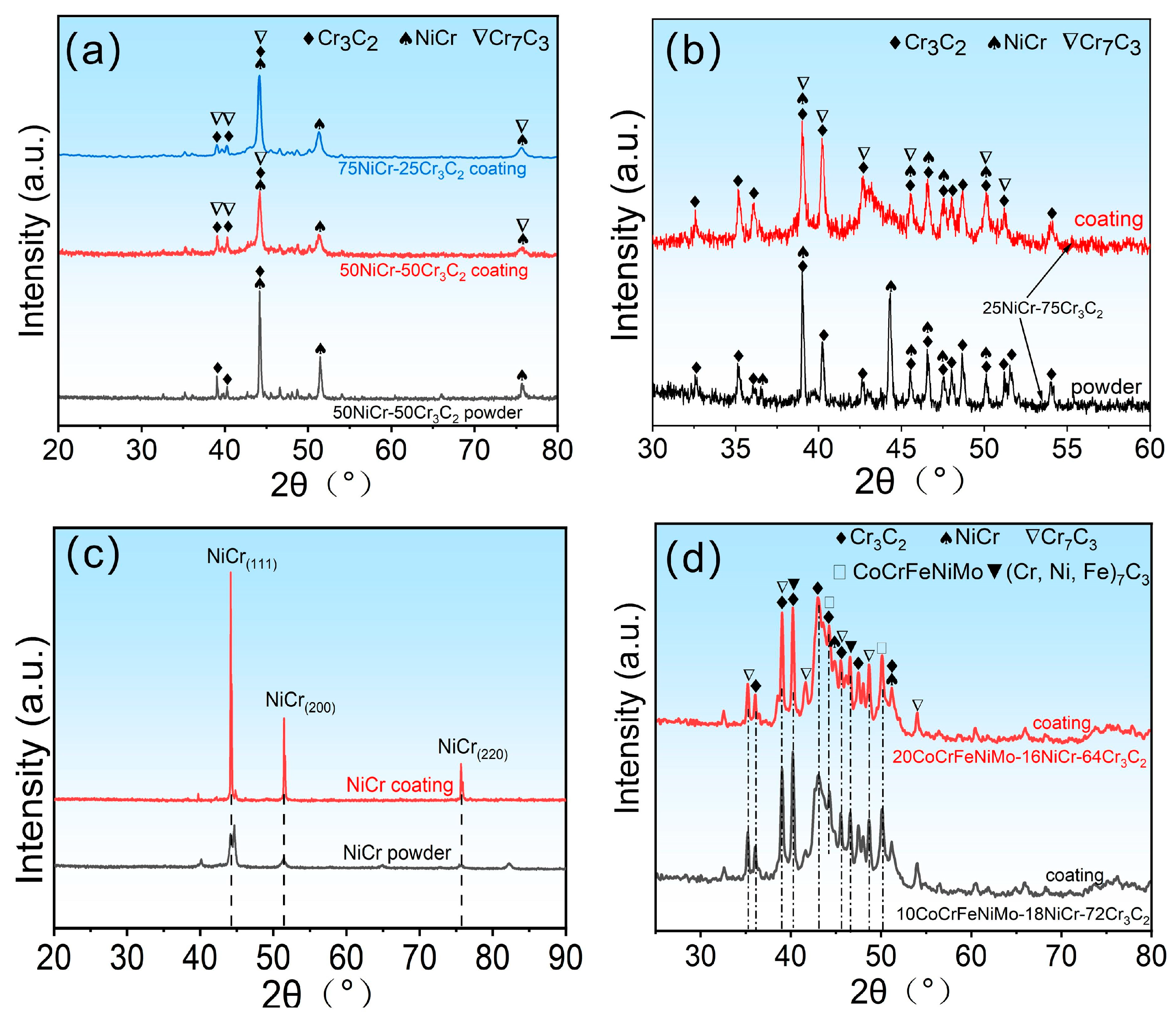

3.1. XRD Analysis of Coatings and Powders

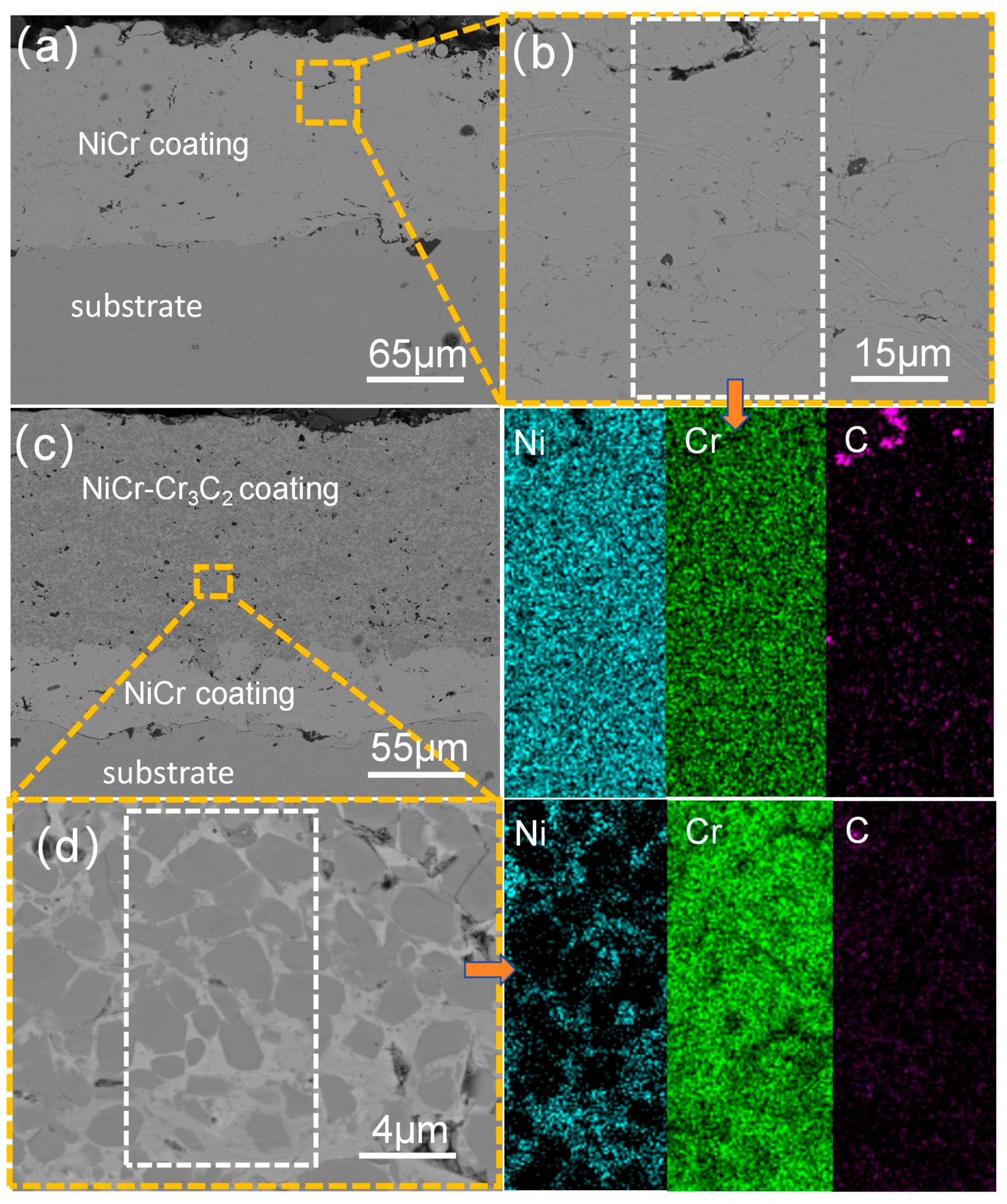

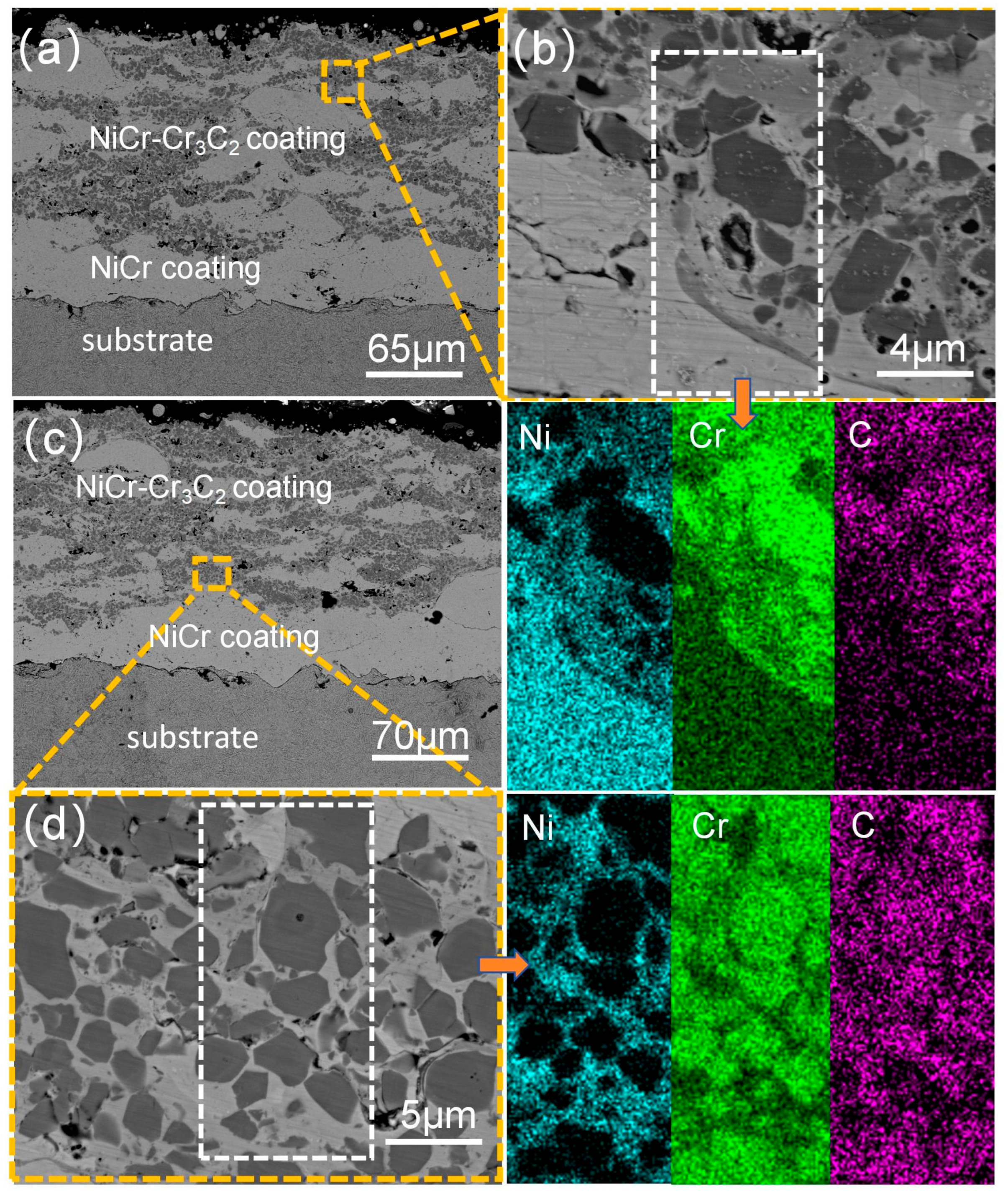

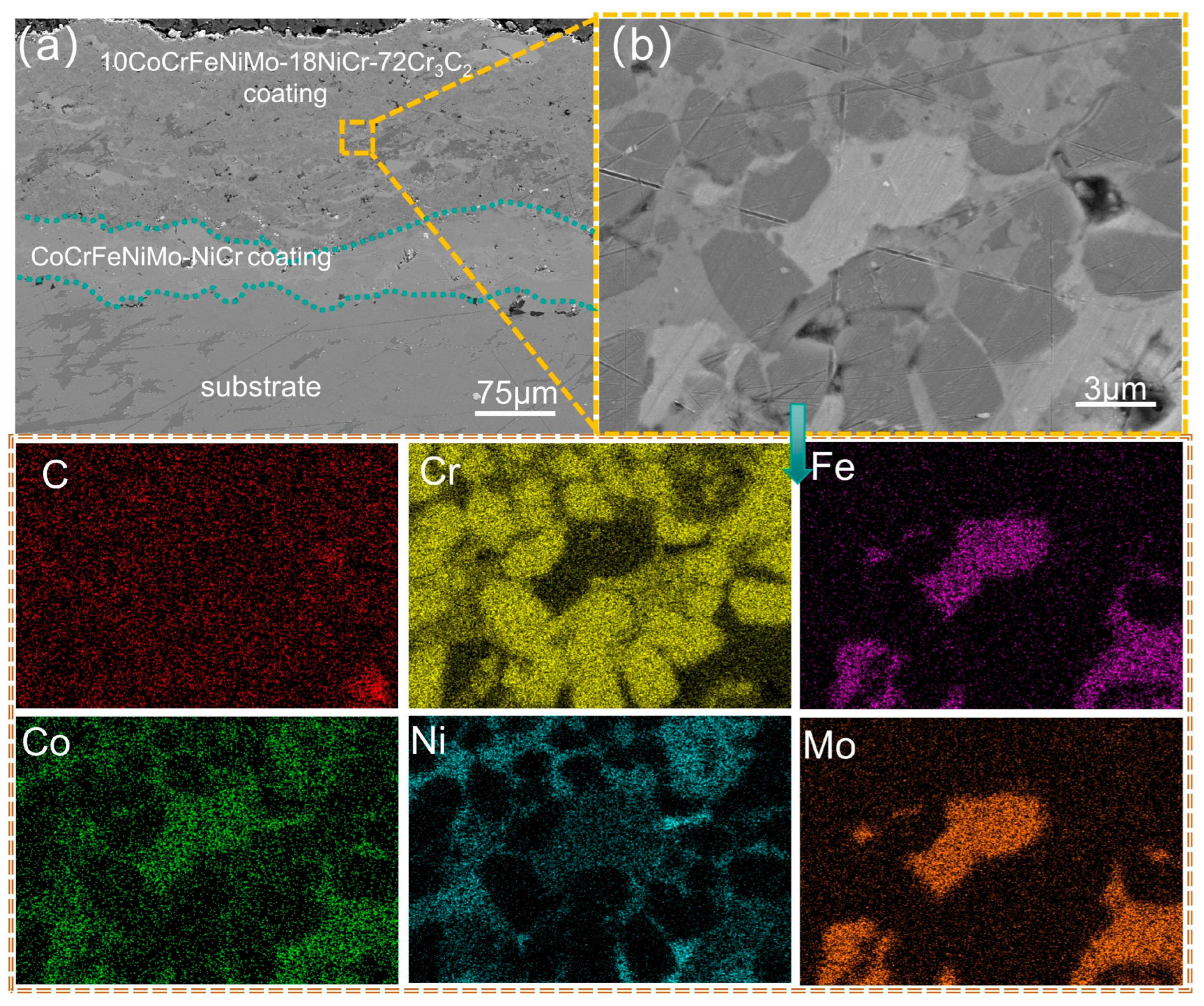

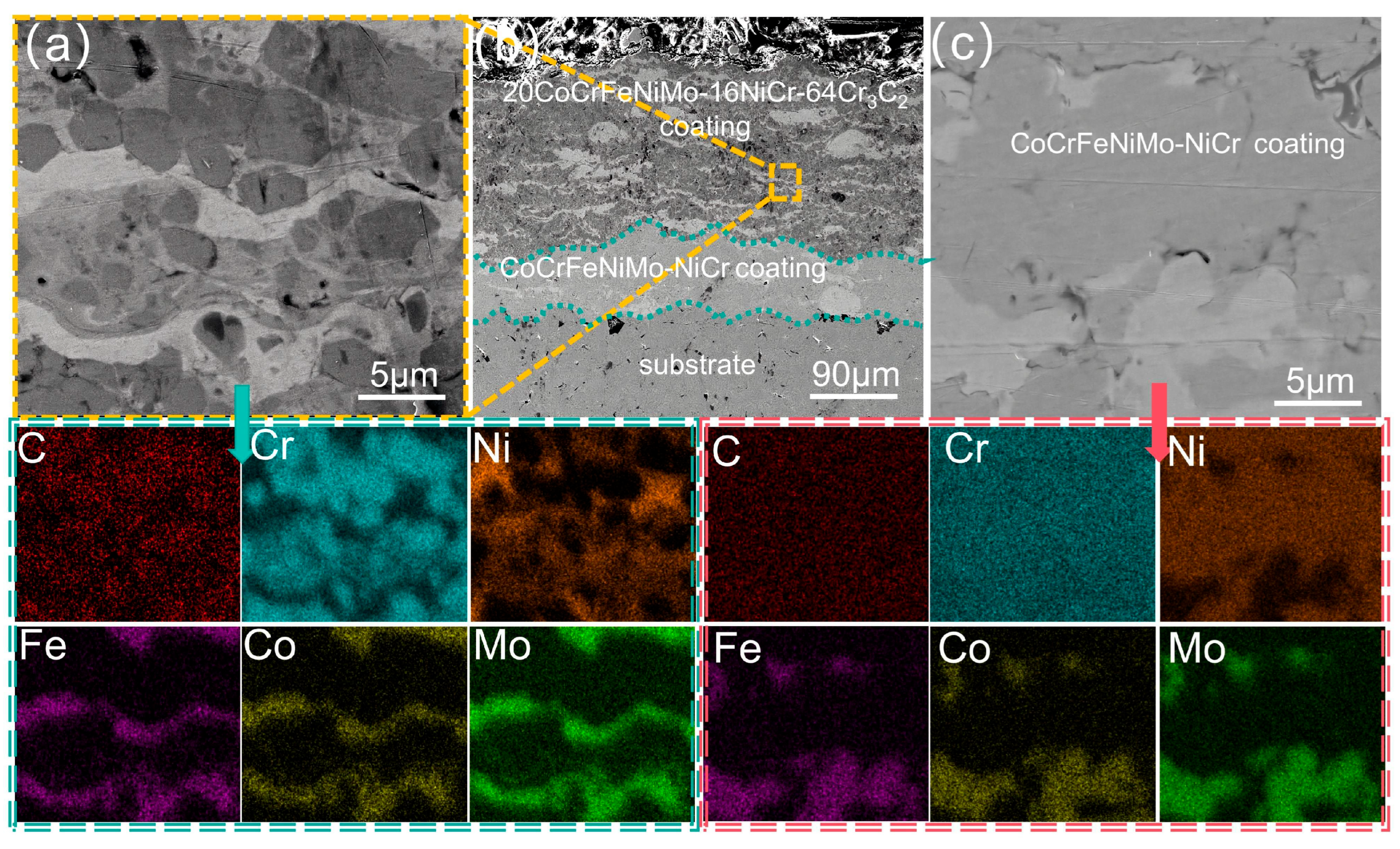

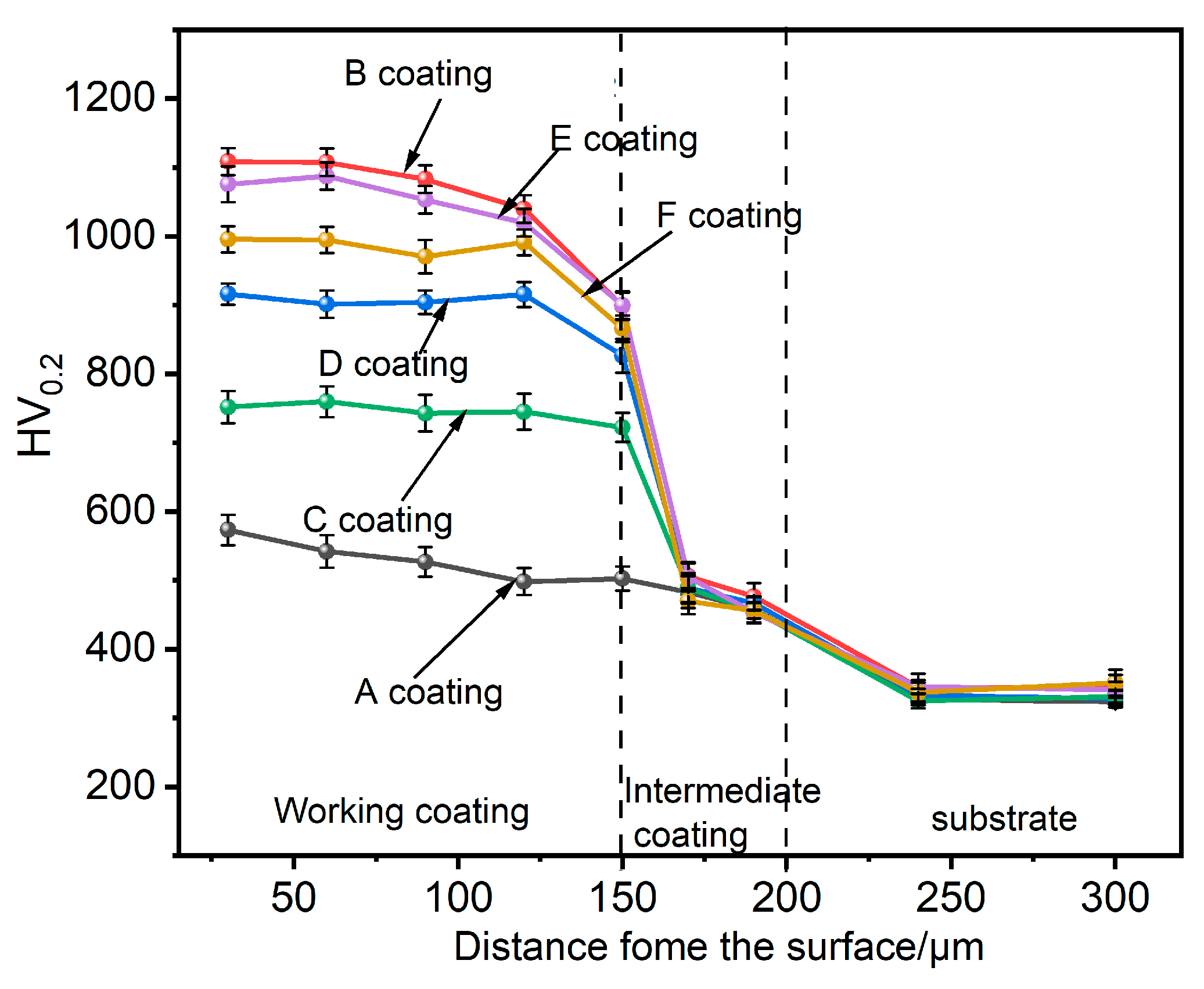

3.2. Analysis of the Cross-Sectional Microstructure of the Coating

3.3. Coating Performance Analysis

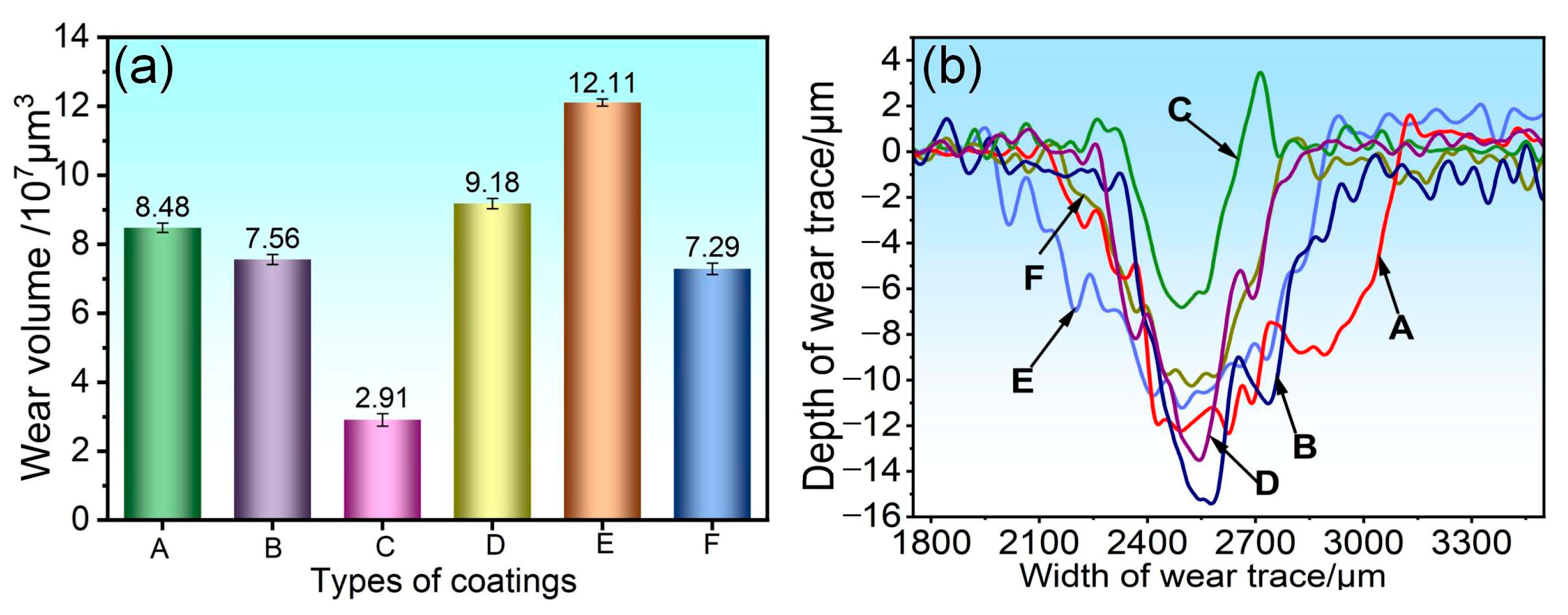

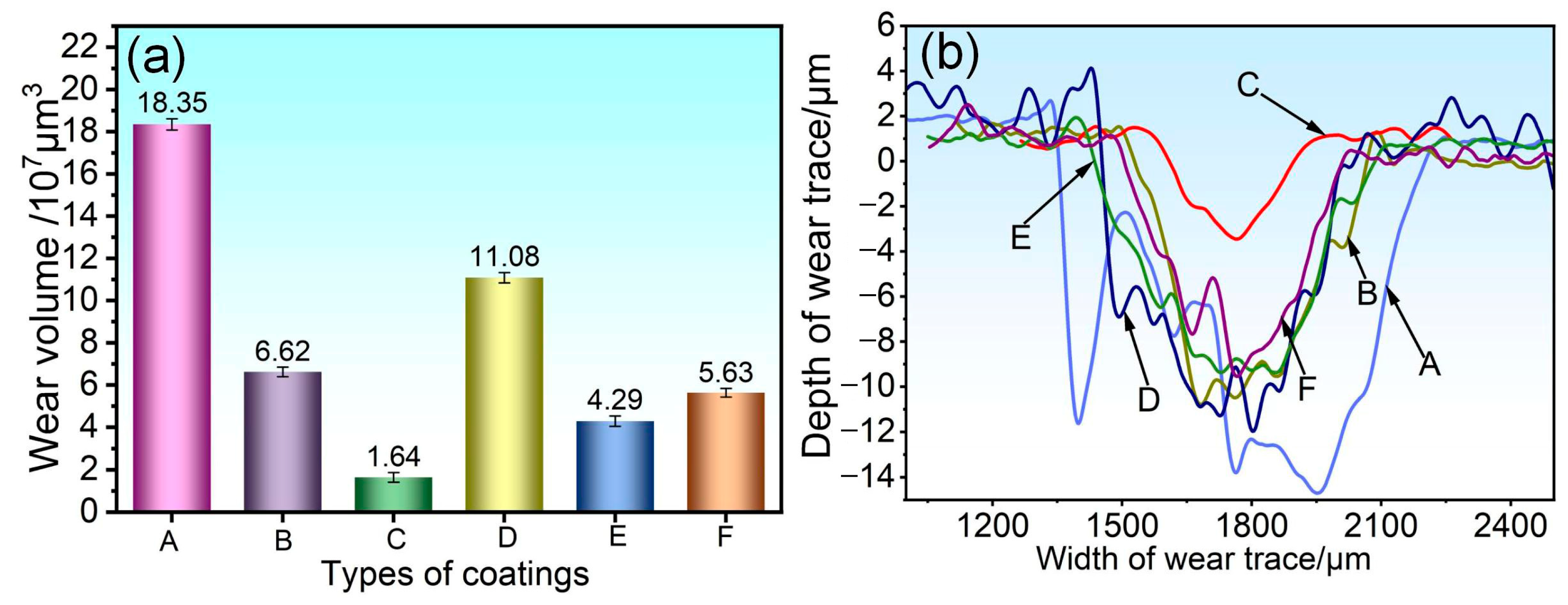

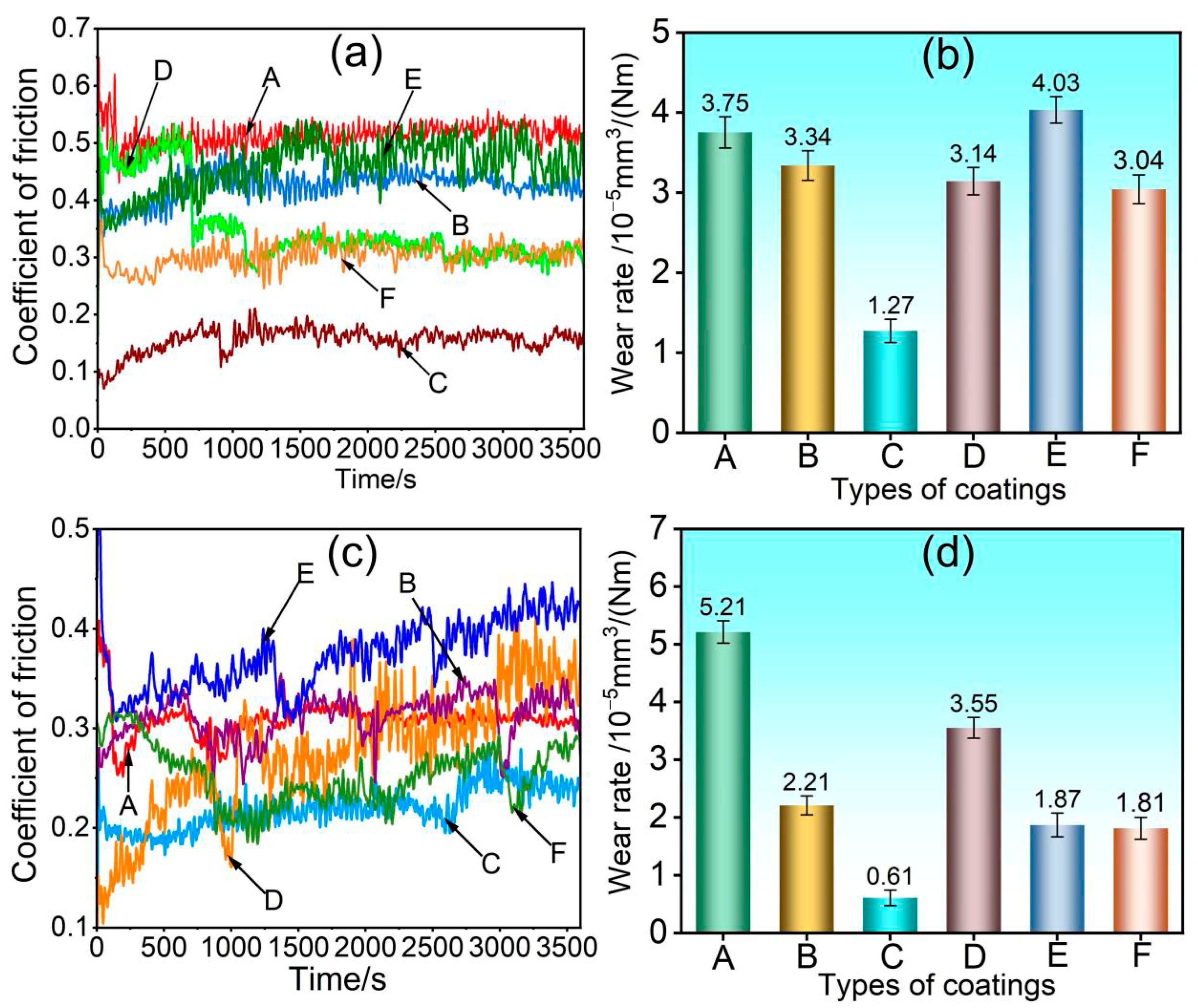

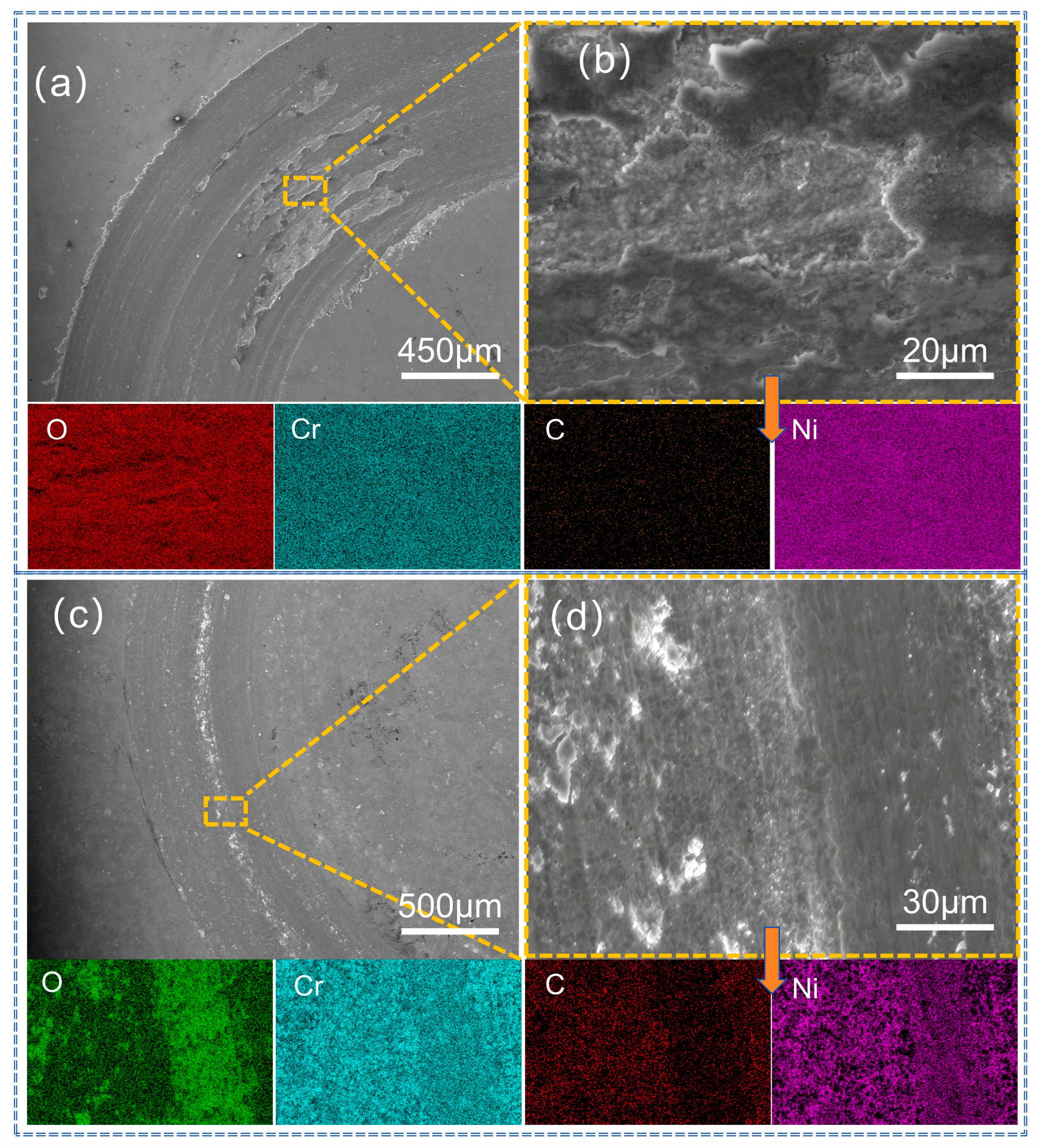

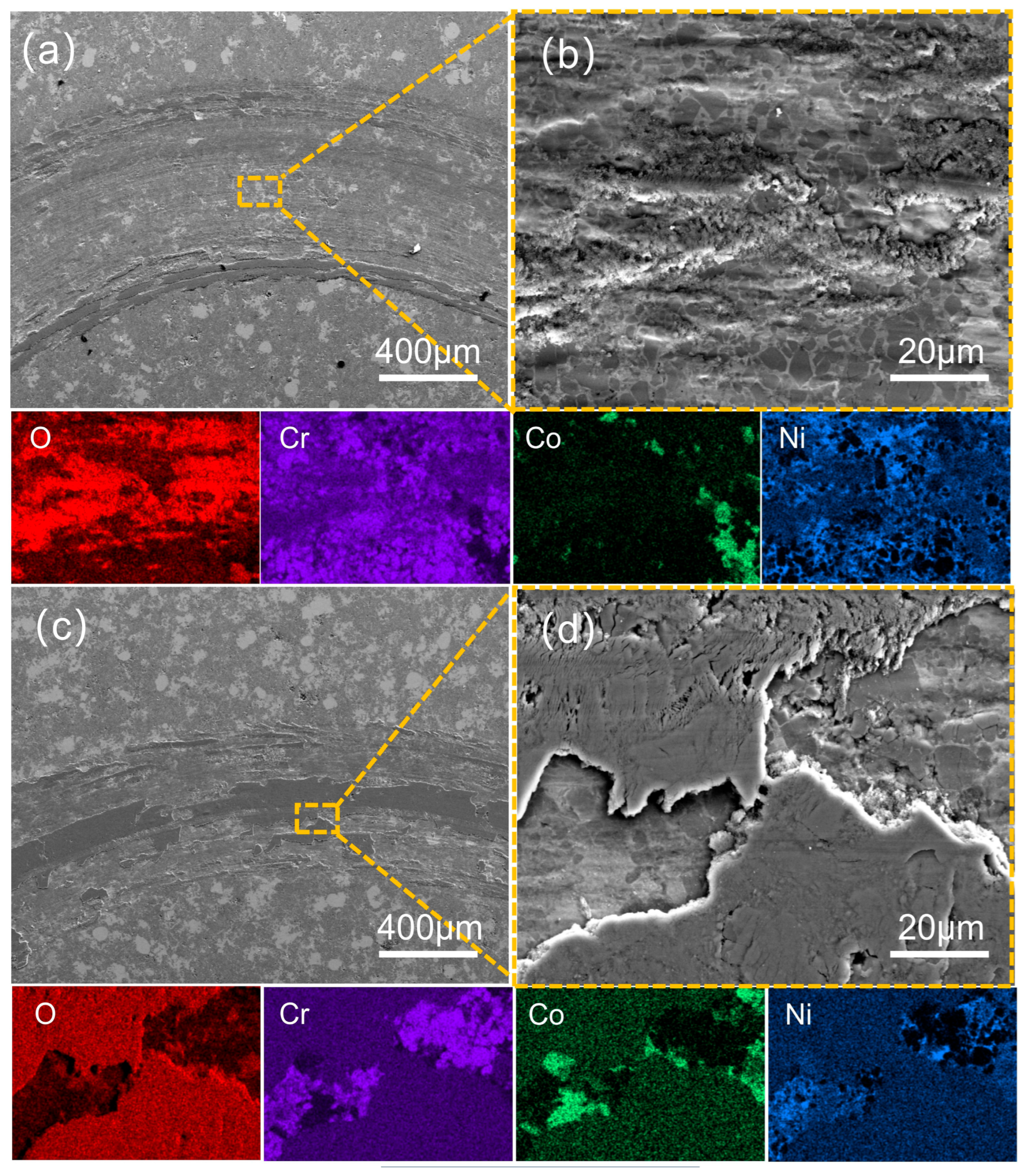

3.4. Analysis of Abrasion Morphology and Wear Mechanism of Coatings

| EDS Area | Ni | Cr | C | O | Fe | Co | Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 12b | 29.9 | 9.4 | 12.1 | 48.6 | -- | -- | -- |

| Figure 12d | 11.5 | 35.8 | 32.2 | 20.5 | -- | -- | -- |

| Figure 13b | 36.7 | 12.3 | 11.8 | 39.2 | -- | -- | -- |

| Figure 13d | 13.8 | 36.7 | 30.4 | 19.1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Figure 14b | 19.1 | 26.4 | 14.3 | 40.2 | -- | -- | -- |

| Figure 14d | 15.8 | 34.3 | 34.7 | 15.2 | -- | -- | -- |

| Figure 15b | 18.4 | 29.3 | 13.9 | 38.4 | -- | -- | -- |

| Figure 15d | 15.6 | 37.6 | 32.8 | 14.0 | -- | -- | -- |

| Figure 16b | 11.7 | 30.0 | 18.8 | 35.0 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Figure 16d | 9.9 | 28.3 | 21.7 | 34.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Figure 17b | 13.0 | 31.4 | 16.2 | 33.4 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Figure 17d | 10.3 | 26.9 | 14.2 | 40.5 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.7 |

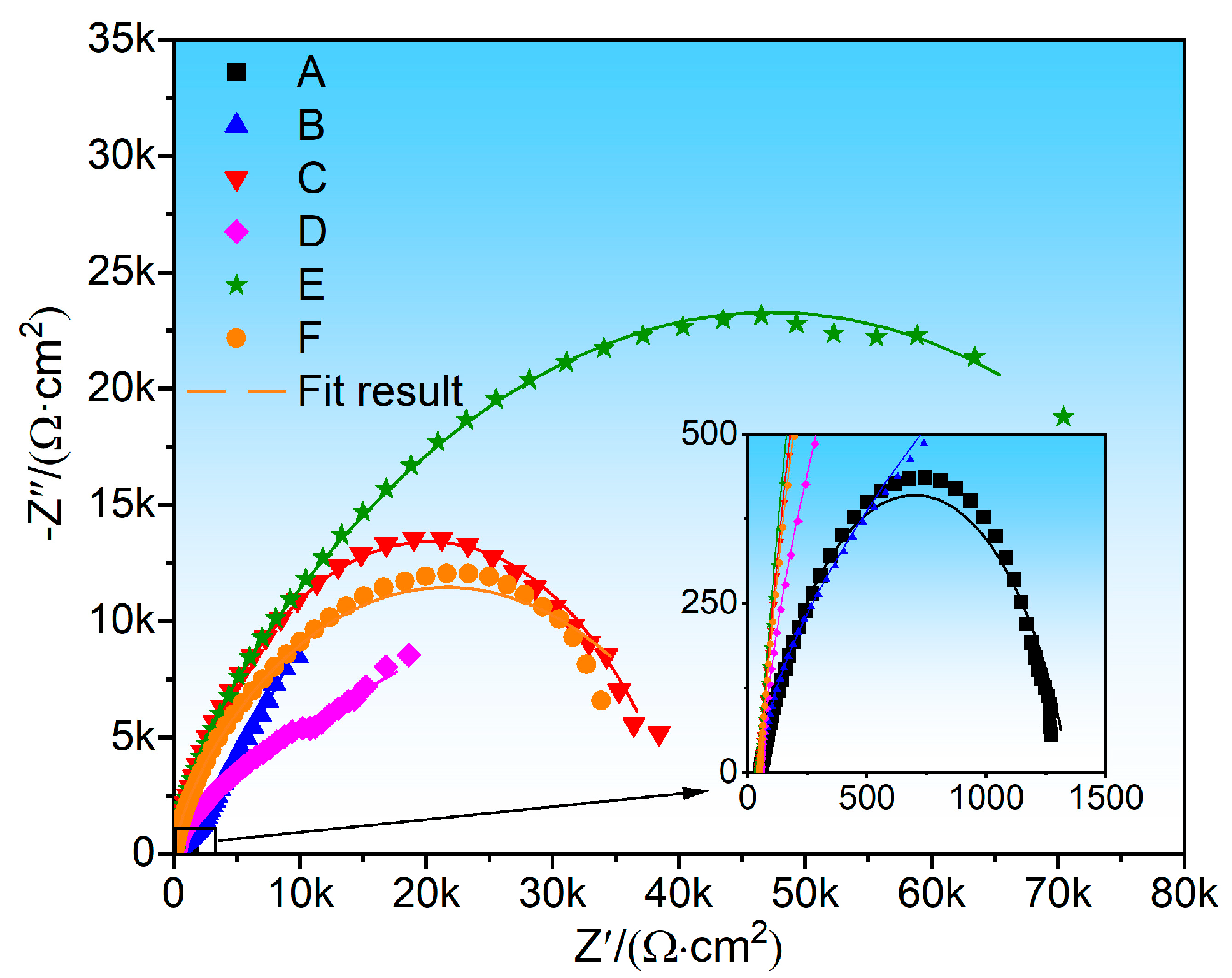

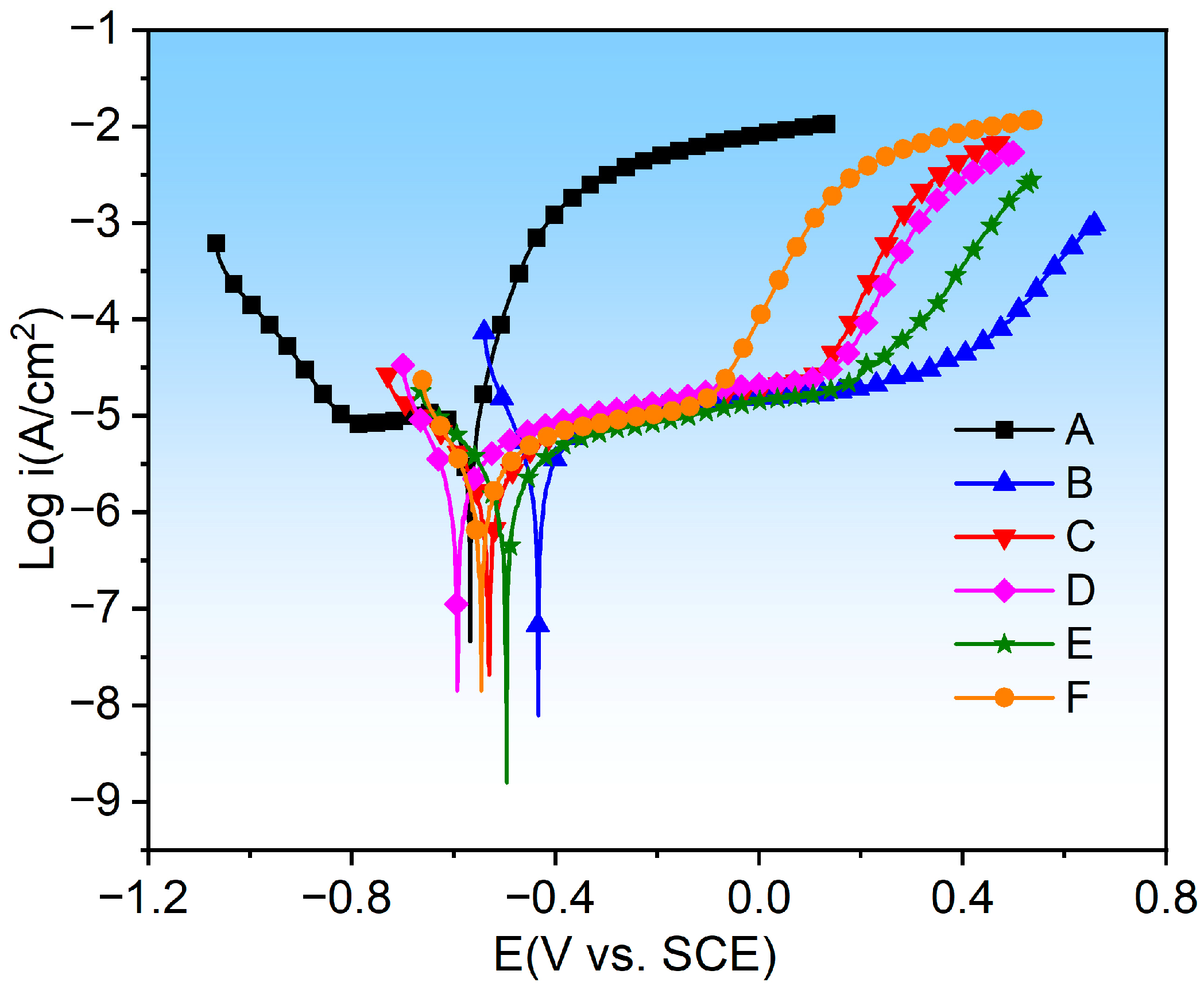

3.5. Electrochemical Performance Analysis

4. Conclusions

- Compared with the 25NiCr-75Cr3C2 (B) and 50NiCr-50Cr3C2 (D) coatings, the porosity of the 75NiCr-25Cr3C2 (C), 10CoCrFeNiMo-18NiCr-72Cr3C2 (E) and 20CoCrFeNiMo-16NiCr-64Cr3C2 (F) coatings was significantly reduced. It is worth noting that the introduction of CoCrFeNiMo high-entropy alloy has a significant effect on inhibiting pore formation and enhancing the coating’s density, which is conducive to improving the overall quality of the coating.

- When subjected to friction and wear at 350 °C and 500 °C, a stable oxide film was formed on the surface of the 75NiCr-25Cr3C2 coating (C). The wear mechanism was mainly oxidative wear, and thus it exhibited the best tribological performance at both temperatures, with the lowest friction coefficient and wear rate.

- Compared with the friction and wear at 350 °C, the wear rate and wear scar depth of the C, B, E and F coatings at 500 °C were significantly reduced, and the tribological performance was significantly improved. Among them, the wear rate of the E and F coatings was less than half of that at 350 °C, indicating that the addition of CoCrFeNiMo high-entropy alloy effectively enhanced the high-temperature wear resistance of the NiCr-Cr3C2 coating.

- At 350 °C, coatings B, D, E, and F primarily undergo abrasive wear, with oxidative wear as a secondary mechanism. Under these conditions, the oxide film provides limited protection, resulting in relatively severe material loss. At 500 °C, coatings B and D continue to experience abrasive wear as the dominant mechanism; however, the oxide film contributes to lubrication and protection, leading to a moderate improvement in wear resistance. In contrast, coatings E and F exhibit a transition to oxidative wear as the primary mechanism, accompanied by a notable enhancement in tribological performance.

- In terms of electrochemical corrosion performance, the E coating has the best corrosion resistance, followed by the C coating. The subsequent order of corrosion resistance is F, B, D, and A coatings, and the NiCr coating (A) has the poorest corrosion resistance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ding, Y.; Hussain, T.; McCartney, D. High-temperature oxidation of HVOF thermally sprayed NiCr–Cr3C2 coatings: Microstructure and kinetics. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 6808–6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Lu, H.; Qi, X.; Yang, B.; Li, C.; Yu, P.; Cao, Y. High temperature oxidation behavior and interface diffusion of Cr3C2-NiCrCoMo/nano-CeO2 composite coatings. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 905, 164177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matikainen, V.; Bolelli, G.; Koivuluoto, H.; Honkanen, M.; Vippola, M.; Lusvarghi, L.; Vuoristo, P. A study of Cr3C2-based HVOF- and HVAF-sprayed coatings: Microstructure and carbide retention. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2017, 26, 1239–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhou, K.; Li, Y.; Deng, C.; Zeng, K. High temperature wear performance of HVOF-sprayed Cr3C2-WC-NiCoCrMo and Cr3C2-NiCr hardmetal coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 416, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolelli, G.; Berger, L.M.; Börner, T.; Koivuluoto, H.; Matikainen, V.; Lusvarghi, L.; Lyphout, C.; Markocsan, N.; Nylén, P.; Sassatelli, P.; et al. Sliding and abrasive wear behaviour of HVOF- and HVAF-sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr hardmetal coatings. Wear 2016, 358–359, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolelli, G.; Berger, L.-M.; Bonetti, M.; Lusvarghi, L. Comparative study of the dry sliding wear behaviour of HVOF-sprayed WC–(W,Cr)2C–Ni and WC–CoCr hardmetal coatings. Wear 2014, 309, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Li, G.-L.; Wang, H.-D.; Kang, J.-J.; Xu, Z.-L.; Wang, H.-J. Structure and wear behavior of NiCr–Cr3C2 coatings sprayed by supersonic plasma spraying and high velocity oxy-fuel technologies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 356, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, D. Structural characteristics and wear, oxidation, hot corrosion behaviors of HVOF sprayed Cr3C2-NiCr hardmetal coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 457, 129319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgal, D.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Prakash, S. Corrosion behavior of bare, Cr3C2-25%(NiCr), and Cr3C2-25%(NiCr)+0.4%CeO2-coated superni 600 under molten salt at 900 °C. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 23, 3805–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, D.; Legoux, J.-G.; Lima, R.S. Engineering HVOF-sprayed Cr3C2-NiCr coatings: The effect of particle morphology and spraying parameters on the microstructure, properties, and high temperature wear performance. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2013, 22, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, F.; Merino, D.; Silvestri, A.T.; Munez, C.; Poza, P. Mechanical properties optimization of Cr3C2-NiCr coatings produced by compact plasma spray process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 465, 129570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Yan, J.; Wei, T.; Wu, J.; Yang, H. Microstructure and tribological performances of Cr3C2- and B4C-added CoCrFeNiMo HEA coatings prepared by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 511, 132–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriş, R.; Meghwal, A.; Singh, S.; Berndt, C.C.; Ang, A.S.M.; Munroe, P. Exploring the impact of Mo addition in high-velocity oxygen-fuel (HVOF) sprayed CoCrFeNiMo0.5 high-entropy alloy coatings. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1037, 180510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Lu, H.; Qi, X.; Yang, B.; Li, C.; Yu, P.; Wang, J.; Gao, L. The influence of nano-CeO2 on tribological properties and microstructure evolution of Cr3C2-NiCrCoMo composite coatings at high temperature. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 428, 127913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, D.; Jia-jie, K.; Guo-zheng, M.; Yong-kuan, Z.; Zhi-qiang, F.; Li-na, Z.; Ding-shun, S.; Hai-dou, W. Microstructure, mechanical property and high temperature wear mechanism of AlCoCrFeNi/WC composite coatings deposited by HVOF. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 14118–14131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasulu, V.; Manikandan, M. High-temperature corrosion behaviour of air plasma sprayed Cr3C2-25NiCr and NiCrMoNb powder coating on alloy 80A at 900 °C. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 337, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Jadhav, M.; Chakradhar, R.; Muniprakash, M.; Singh, S. Synthesis and properties of high velocity oxy-fuel sprayed FeCoCrNi2Al high entropy alloy coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 378, 124950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.J.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, J.C.; Liu, K.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liang, G.Y.; Gao, Y.; et al. Microstructural design and oxidation resistance of CoNiCrAlY alloy coatings in thermal barrier coating system. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 688, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallimanalan, A.; Babu, S.K.; Muthukumaran, S.; Murali, M.; Mahendran, R.; Gaurav, V.; Manivannan, S. Synthesis, characterisation and erosion behaviour of AlCoCrMoNi high entropy alloy coating. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 116543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Li, W.; Yang, J.; Zhu, S.; Cui, S.; Li, X.; Shao, L.; Zhai, H. Effect of Cr3C2 content on microstructure, mechanical and tribological properties of Ni3Al-based coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 466, 129597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.-y.; Li, Y.-l.; Li, F.-y.; Ran, X.-j.; Zhang, X.-y.; Qi, X.-X. Research on the high temperature oxidation mechanism of Cr3C2–NiCrCoMo coating for surface remanufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Wu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Li, J.; Lin, J. Effect of flow velocity on cavitation erosion behavior of HVOF sprayed WC-10Ni and WC-20Cr3C2–7Ni coatings. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2020, 92, 105330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liang, J.; Zhou, J. Effects of WS2 and Cr3C2 addition on microstructural evolution and tribological properties of the self-lubricating wear-resistant CoCrFeNiMo composite coatings prepared by laser cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 163, 109442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Munagala, V.N.V.; Sharifi, N.; Roy, A.; Alidokht, S.A.; Harfouche, M.; Makowiec, M.; Stoyanov, P.; Chromik, R.R.; Moreau, C. Influence of HVOF spraying parameters on microstructure and mechanical properties of FeCrMnCoNi high-entropy coatings (HECs). J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 4293–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, W.; Wang, B.; Zhao, J.; Zho, Z.; Li, S.; Mao, W. Influence of HVOF spray parameters on tribological behavior in CoCrFeNiMo high-entropy alloy coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 518, 132856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Hu, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, C. Tribological properties of atmospheric plasma sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr/20% nickel-coated graphite self-lubricating coatings. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 38040–38050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, L.; Mudgal, D.; Singh, S.; Prakash, S. A comparative study to evaluate the corrosion performance of Zr incorporated Cr3C2-(NiCr) coating at 900 °C. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 6479–6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alroy, R.J.; Kamaraj, M.; Sivakumar, G. Microstructure, property and high-temperature wear performance of Cr3C2-based coatings deposited by conventional and ID-HVAF spray torches: A comparative study. Wear 2024, 552–553, 205451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ge, M.; Hu, B.; Qu, X.; Gao, Y. High-temperature wear behavior and mechanisms of self-healing NiCrAlY-Cr3C2-Ti2SnC coating prepared by atmospheric plasma spraying. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2024, 33, 2433–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, P.; Kaur, M. Wear and friction characteristics of atmospheric plasma sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr coatings. Tribol. Mater. Surf. Interfaces 2020, 14, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, P.; Kaur, M.; Singh, S. High temperature tribological performance of atmospheric plasma sprayed Cr3C2-NiCr coating on H13 tool steel. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 33, 1518–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ge, M.; Qu, X.; Gao, Y. Improved high-temperature tribological properties of Ti3SiC2 modified NiCr-Cr3C2 coatings and their wear mechanism. Surf. Coat. Technol 2025, 501, 131943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janka, L.; Norpoth, J.; Trache, R.; Berger, L.-M. Influence of heat treatment on the abrasive wear resistance of a Cr3C2-NiCr coating deposited by an ethene-fuelled HVOF spray process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 291, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Jayaganthan, R.; Prakash, S. Evaluation of cyclic hot corrosion behaviour of detonation gun sprayed Cr3C2–25% NiCr coatings on nickel-and iron-based superalloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009, 203, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Wang, W.; Qi, W.; Li, W.; Xie, L. Preparation process, surface properties and mechanistic study of HVAF-sprayed CoCrFeNiMo0.2 high-entropy alloy coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 494, 131423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvello, A.; Diaz, E.T.; Ramirez, E.R.; Cano, I.G. Microstructural, mechanical and wear properties of atmospheric plasma-sprayed and high-velocity oxy-fuel AlCoCrFeNi equiatomic high-entropy alloys (HEAs) coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2023, 32, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liang, J.; Zhou, J. Microstructure and elevated temperature tribological performance of the CoCrFeNiMo high entropy alloy coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 449, 128978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhai, Q.; Zhai, C.; Zheng, H. Oxidation and failure mechanisms of CoCrFeNiMo HEA coatings at 1000 °C: Insights into TGO evolution and interface diffusion. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 509, 132229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.-Y.; Li, F.-Y.; Li, Y.-L.; Wang, L.-M.; Lu, H.-Y.; Ran, X.-J.; Zhang, X.-Y. Influences of plasma arc remelting on microstructure and service performance of Cr3C2-NiCr/NiCrAl composite coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 369, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Cheng, W.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J.; Chen, G. Microstructure and tribological behavior of CoCrFeNiMo0. 2/SiC high-entropy alloy gradient composite coating prepared by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 467, 129681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zeng, D.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y. High temperature oxidation and tribological behavior of Cr3C2-25CoNiCrAlY and Cr3C2-25NiCr coatings prepared by AC-HVAF. China Surf. Eng. 2017, 30, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Xu, J.; Ye, Z.; Li, X.; Luo, J. Microwave sintered porous CoCrFeNiMo high entropy alloy as an efficient electrocatalyst for alkaline oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 79, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X. Microstructure and mechanical properties of CoCrFeNiMo high-entropy alloy coatings. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 5127–5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Chen, S.; Dou, Y.; Han, S.; Wang, L.; Man, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Cheng, Y.F.; Li, X. Passivation behavior and surface chemistry of 2507 super duplex stainless steel in artificial seawater: Influence of dissolved oxygen and pH. Corros. Sci. 2019, 150, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medabalimi, S.; Hebbale, A.M.; Gudala, S.; Ramesh, M.; Gujar, R.; Aravindan, N.; Petru, J. Studies on high-temperature erosion behaviour of HVOF sprayed NiCr based composite coatings. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhao, L.; Chen, W.; Luo, J.; Zhou, H.; Wu, X.; Zheng, X. High-temperature tribological behavior and microstructural evolution of HVOF-sprayed (NiCr-Cr3C2)/NiCr coatings: A study from 600 to 1000 °C. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 514, 132579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.; Khorrami, M.S.; Sohi, M.H. Effect of molybdenum content on the microstructural characteristic of surface cladded CoCrFeNi high entropy on AISI420 martensitic stainless steel. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 43, 111729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xia, G.; Yan, H.; Xin, Y.; Song, H.; Luo, C.; Guan, H.; Luc, C.; Hu, Z. Visualising the adsorption behaviour of sodium dodecyl sulfate corrosion inhibitor on the Mg alloy surface by a novel fluorescence labeling strategy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 642, 158624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Dzhurinskiy, D.; Dautov, S.; Shornikov, P. Structure and electrochemical behavior of atmospheric plasma sprayed Cr3C2-NiCr cermet composite coatings. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2023, 111, 106105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.; Luo, C.; Song, H.; Yan, H.; Lin, L.; Hu, Z. Experimental and theoretical study of 2-mercaptopyridine as an effective eco-friendly inhibitor for copper in aqueous NaCl. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 382, 121924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types of Powder | d10 | d50 | d90 |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiC | ~20 μm | ~45 μm | ~70 μm |

| 25NiCr-75Cr3C2 | ~12 μm | ~25 μm | ~35 μm |

| 75NiCr-25Cr3C2 | ~18 μm | ~35 μm | ~60 μm |

| 50NiCr-50Cr3C2 | ~15 μm | ~32 μm | ~52 μm |

| 10CoCrFeNiMo | ~30 μm | ~50 μm | ~65 μm |

| 10CoCrFeNiMo-18NiCr-72Cr3C2 | ~13 μm | ~40 μm | ~61 μm |

| 20CoCrFeNiMo−16NiCr-64Cr3C2 | ~12 μm | ~46 μm | ~63 μm |

| Coating Parameters | A | B | C | D | E | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working layer | NiCr | 25NiCr -75Cr3C2 | 75NiCr -25Cr3C2 | 50NiCr -50Cr3C2 | 10CoCrFeNiMo -18NiCr-72Cr3C2 | 20CoCrFeNiMo-16NiCr-64Cr3C2 |

| Transition layer | NiCr | NiCr | NiCr | NiCr | NiCr-CoCrFeNiMo | NiCr-CoCrFeNiMo |

| Powder feed rate (g/min) | 55–60 | |||||

| Oxygen flow rate (LPM) | 1850 | 1900 | ||||

| Propylene flow rate (LPM) | 6 | |||||

| Air flow rate (LPM) | 21 | 26 | ||||

| Spray Distance (mm) | 360 | 310 | ||||

| Traverse speed (mm/s) | 500 | |||||

| Deposition Efficiency (%) | 72.3–75.8 | |||||

| Friction and Wear Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Load (N) | 15 |

| Radius (mm) | 2 |

| Rotational speed (r/min) | 200 |

| Time (min) | 60 |

| Friction temperature (°C) | 350 °C and 500 °C |

| Ambient temperature (°C) | 25 °C |

| Friction pair materials | Al2O3 |

| Sample | Rs (Ω•cm2) | CPEf | Rf (Ω•cm2) | CPEdl | Rct (Ω•cm2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y0f (Ω−1•cm−2•sn) | n | Y0f (Ω−1•cm−2•sn) | n | ||||

| A | 52.69 ± 7.25 | 3.28 × 10−4 | 0.80 | 1293 ± 35 | 9.98 × 10−5 | 0.77 | 3580 ± 33 |

| B | 47.38 ± 6.54 | 9.56 × 10−6 | 0.82 | 418 ± 19 | 7.51 × 10−5 | 0.78 | 1502 ± 21 |

| C | 43.60 ± 7.02 | 2.51 × 10−5 | 0.86 | 10,170 ± 58 | 2.762 × 10−5 | 0.63 | 30,560 ± 77 |

| D | 52.04 ± 8.88 | 8.25 × 10−6 | 0.85 | 989 ± 42 | 5.56 × 10−5 | 0.61 | 2105 ± 19 |

| E | 43.57 ± 7.56 | 1.31 × 10−5 | 0.87 | 12,830 ± 57 | 2.98 × 10−5 | 0.54 | 83,240 ± 85 |

| F | 49.73 ± 6.85 | 1.86 × 10−5 | 0.87 | 5786 ± 36 | 4.18 × 10−5 | 0.53 | 39,640 ± 75 |

| Sample | −Ecorr (mV vs. SCE) | icorr (nA·cm2) | βa | βc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 568 ± 12 | 11.8 ± 2.12 | 0.46 | 13.59 |

| B | 434 ± 11 | 2.55 ± 0.81 | 3.21 | 14.46 |

| C | 530 ± 15 | 2.19 ± 0.95 | 4.07 | 5.57 |

| D | 593 ± 14 | 2.62 ± 0.78 | 3.70 | 12.20 |

| E | 496 ± 9 | 2.08 ± 0.86 | 3.79 | 5.78 |

| F | 546 ± 14 | 2.42 ± 0.93 | 3.70 | 9.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Zhao, L.; Chen, W.; Luo, J.; Zhou, H.; Wu, X.; Zheng, X. Microstructure, Elevated-Temperature Tribological Properties and Electrochemical Behavior of HVOF-Sprayed Composite Coatings with Varied NiCr/Cr3C2 Ratios and CoCrFeNiMo Additions. Coatings 2025, 15, 1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121415

Zhang D, Zhao L, Chen W, Luo J, Zhou H, Wu X, Zheng X. Microstructure, Elevated-Temperature Tribological Properties and Electrochemical Behavior of HVOF-Sprayed Composite Coatings with Varied NiCr/Cr3C2 Ratios and CoCrFeNiMo Additions. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121415

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Daoda, Longzhi Zhao, Wanglin Chen, Junjie Luo, Hongbo Zhou, Xiaoquan Wu, and Xiaomin Zheng. 2025. "Microstructure, Elevated-Temperature Tribological Properties and Electrochemical Behavior of HVOF-Sprayed Composite Coatings with Varied NiCr/Cr3C2 Ratios and CoCrFeNiMo Additions" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121415

APA StyleZhang, D., Zhao, L., Chen, W., Luo, J., Zhou, H., Wu, X., & Zheng, X. (2025). Microstructure, Elevated-Temperature Tribological Properties and Electrochemical Behavior of HVOF-Sprayed Composite Coatings with Varied NiCr/Cr3C2 Ratios and CoCrFeNiMo Additions. Coatings, 15(12), 1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121415