A Damage Model for Predicting Fatigue Life of 0Cr17Ni4Cu4Nb Stainless Steel Under Near-Yield Stress-Controlled Cyclic Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Characterization of the Stress State

2.2. Plasticity Model

3. Experimental Methods and Ductile Fracture Criteria

3.1. Material and Experiments

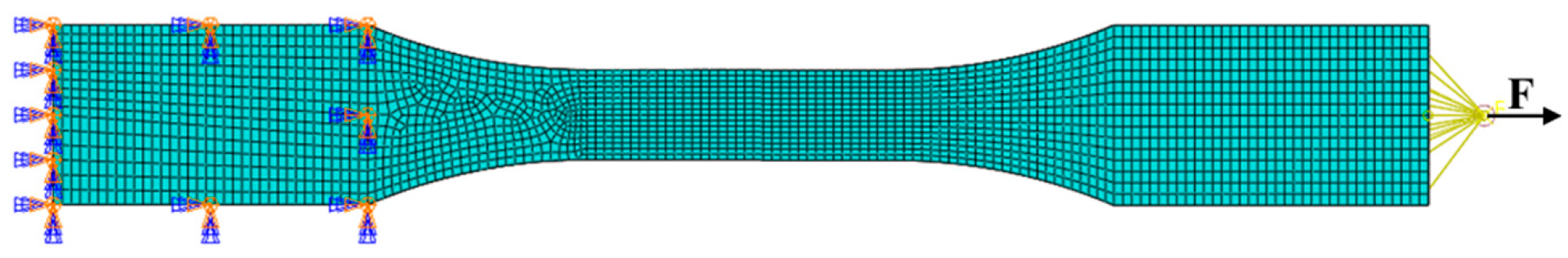

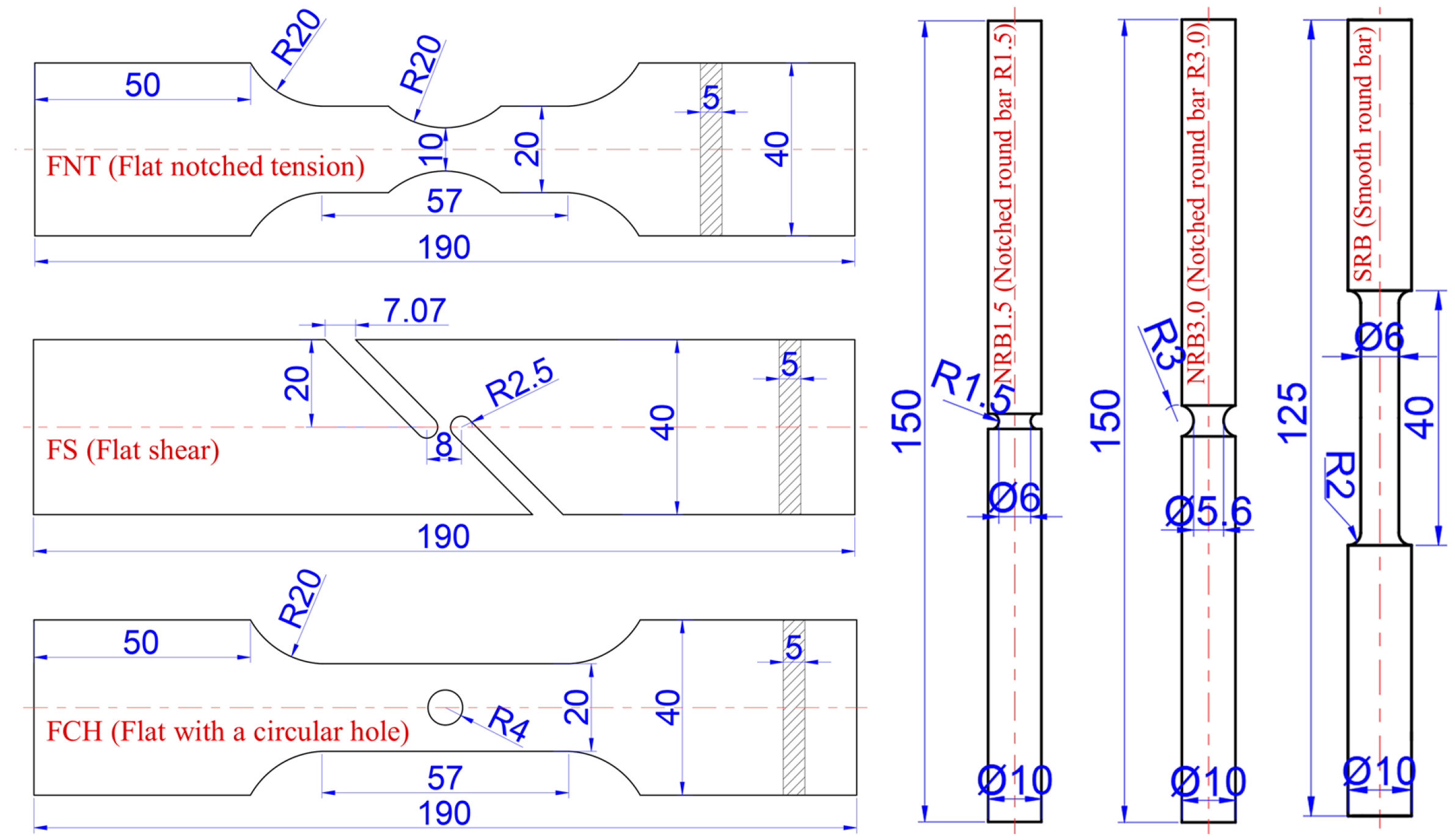

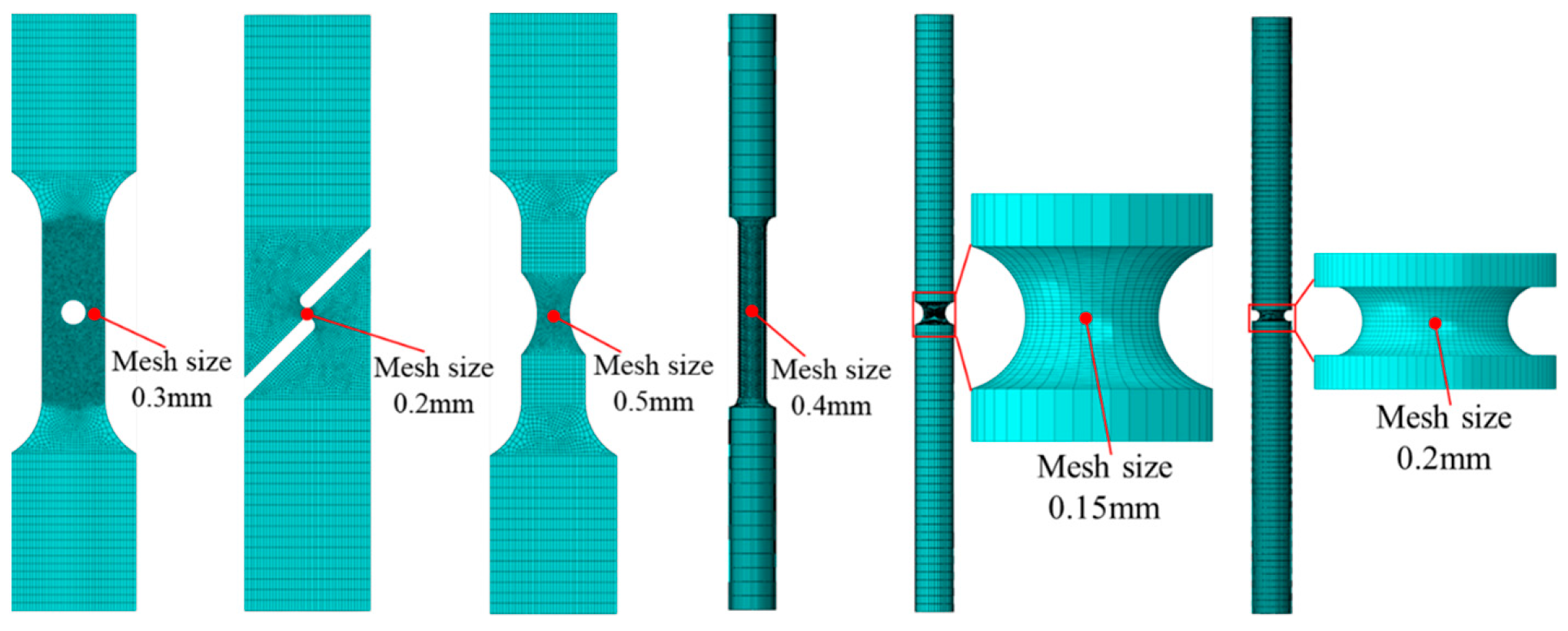

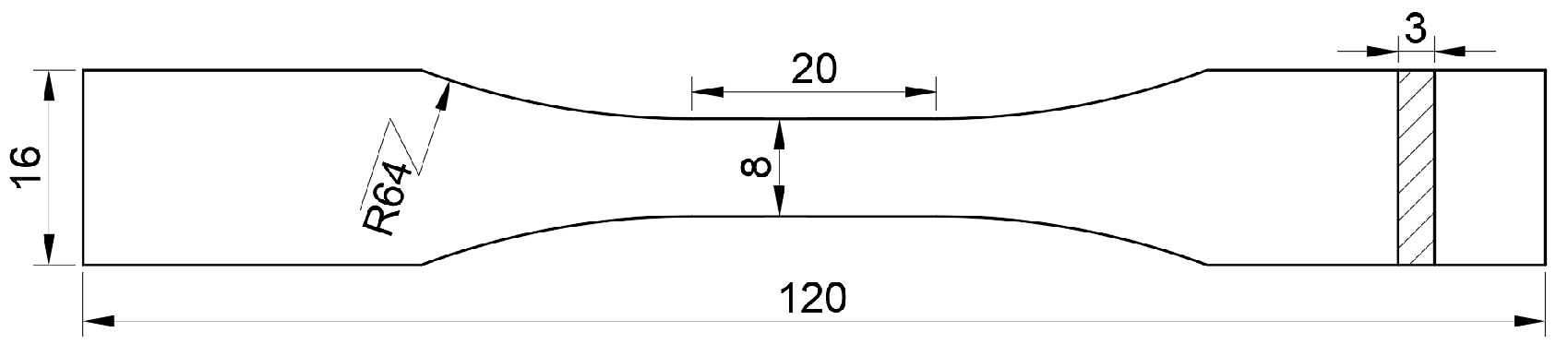

3.2. Finite Element Model

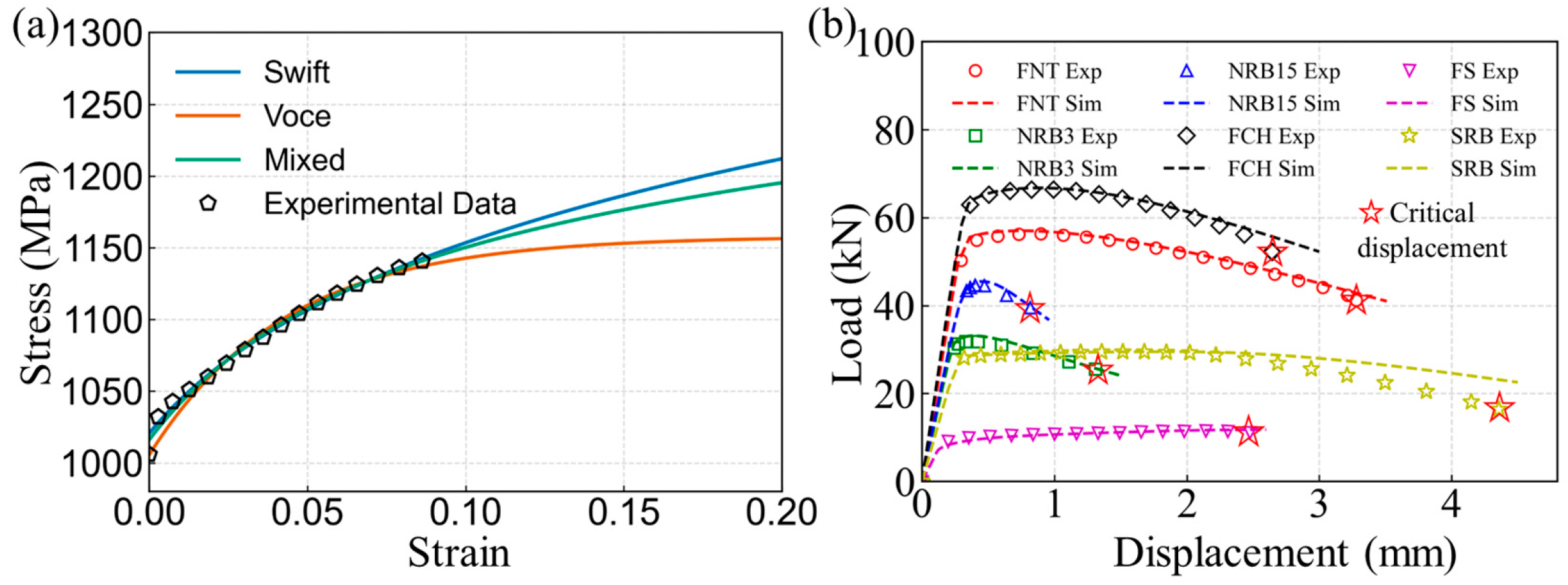

3.3. Hardening Model

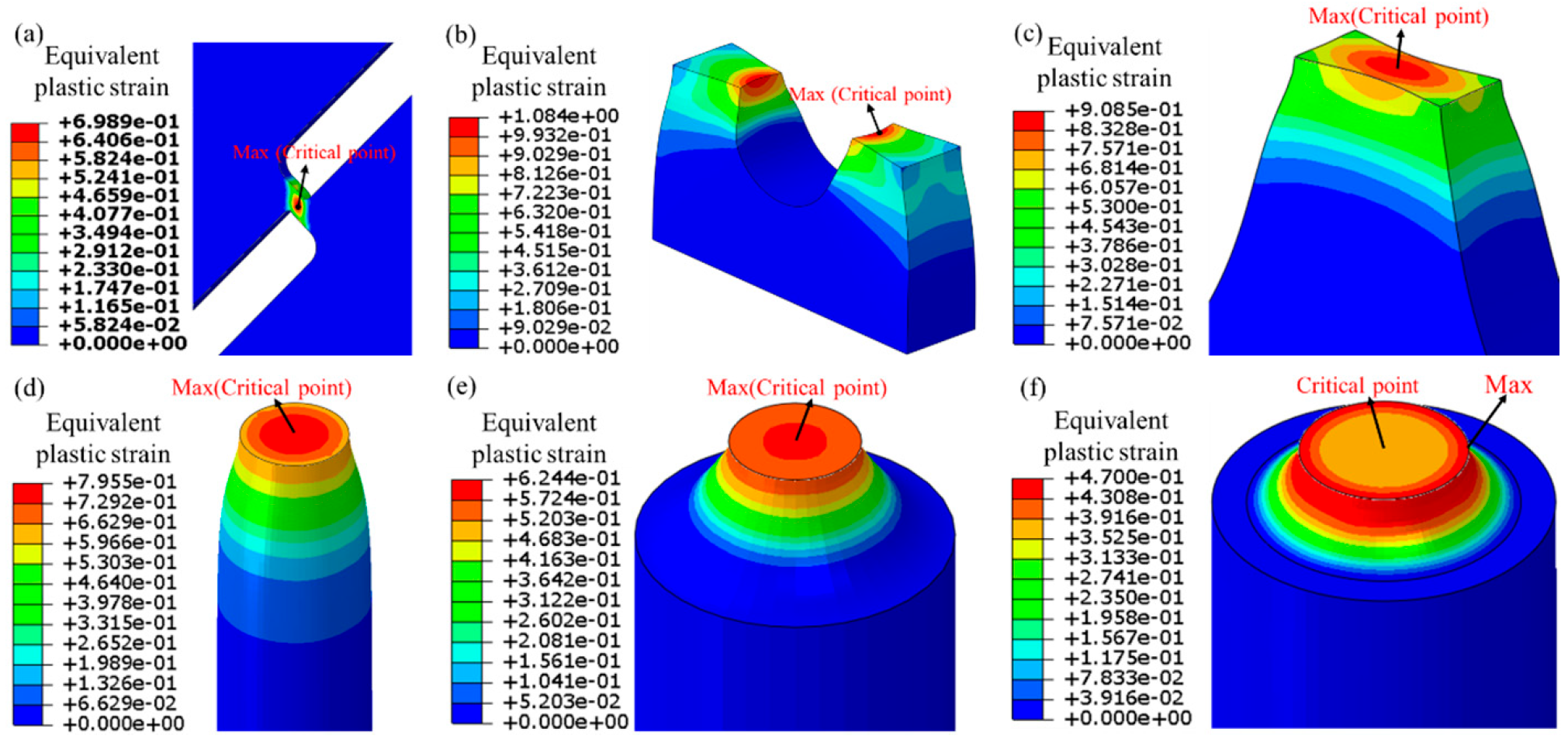

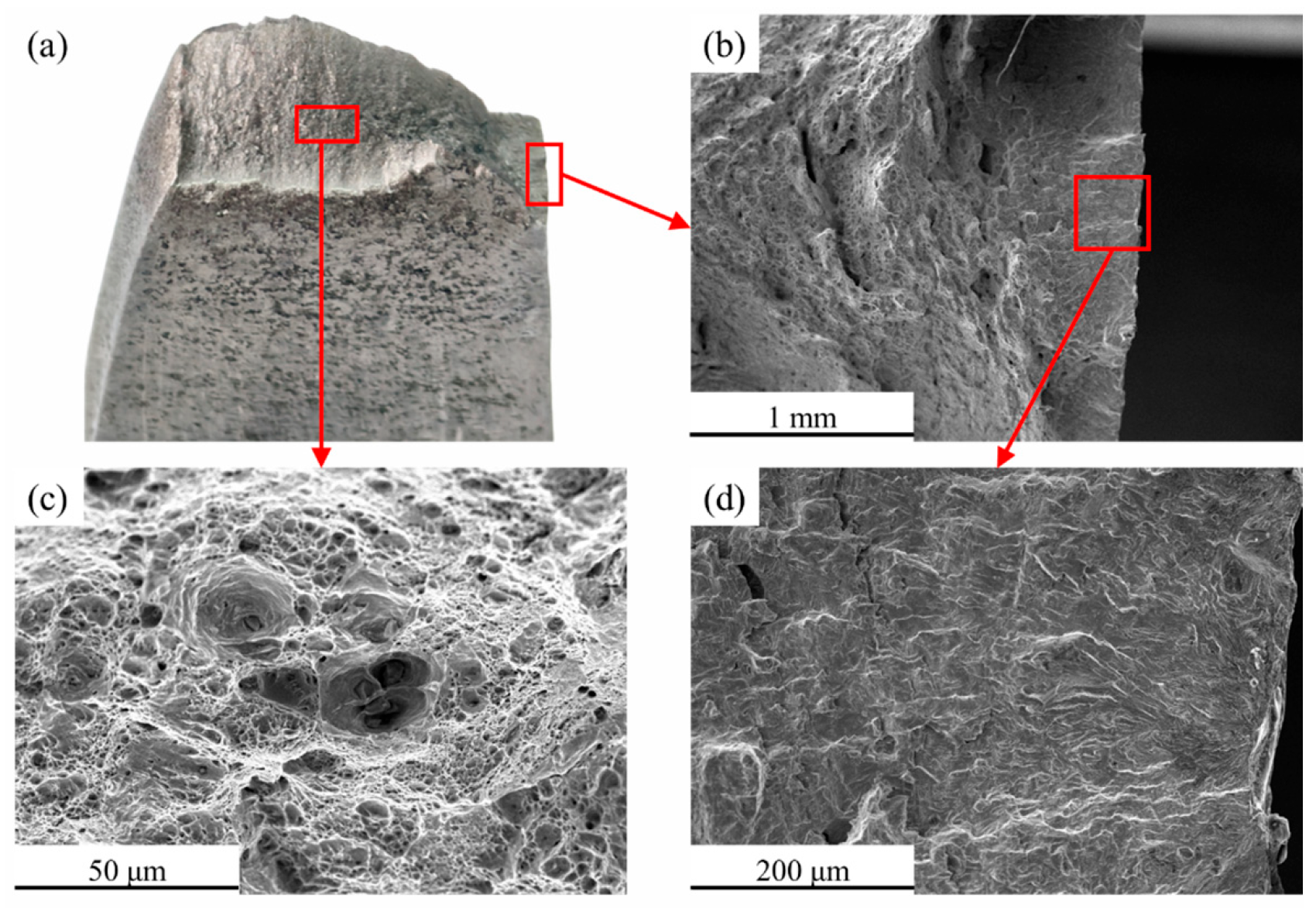

3.4. Damage Fracture Tests

4. Application to Stress-Controlled Cyclic Loading near the Yield Point

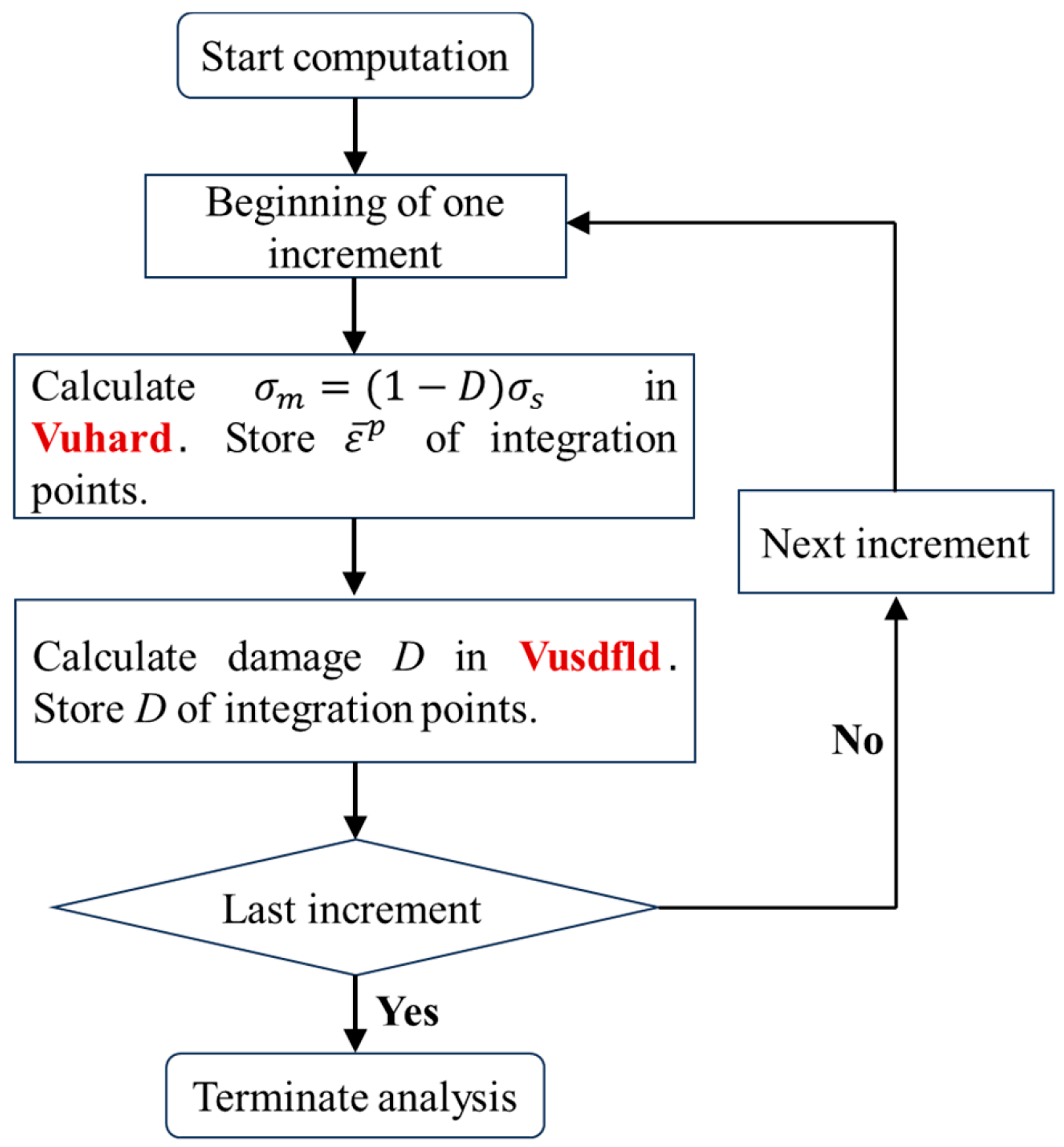

4.1. Damage-Coupled Elastoplastic Fatigue Constitutive Model

4.2. Experiments on Near-Yield Stress-Controlled Cyclic Loading

4.3. Numerical Model

4.4. Numerical Results

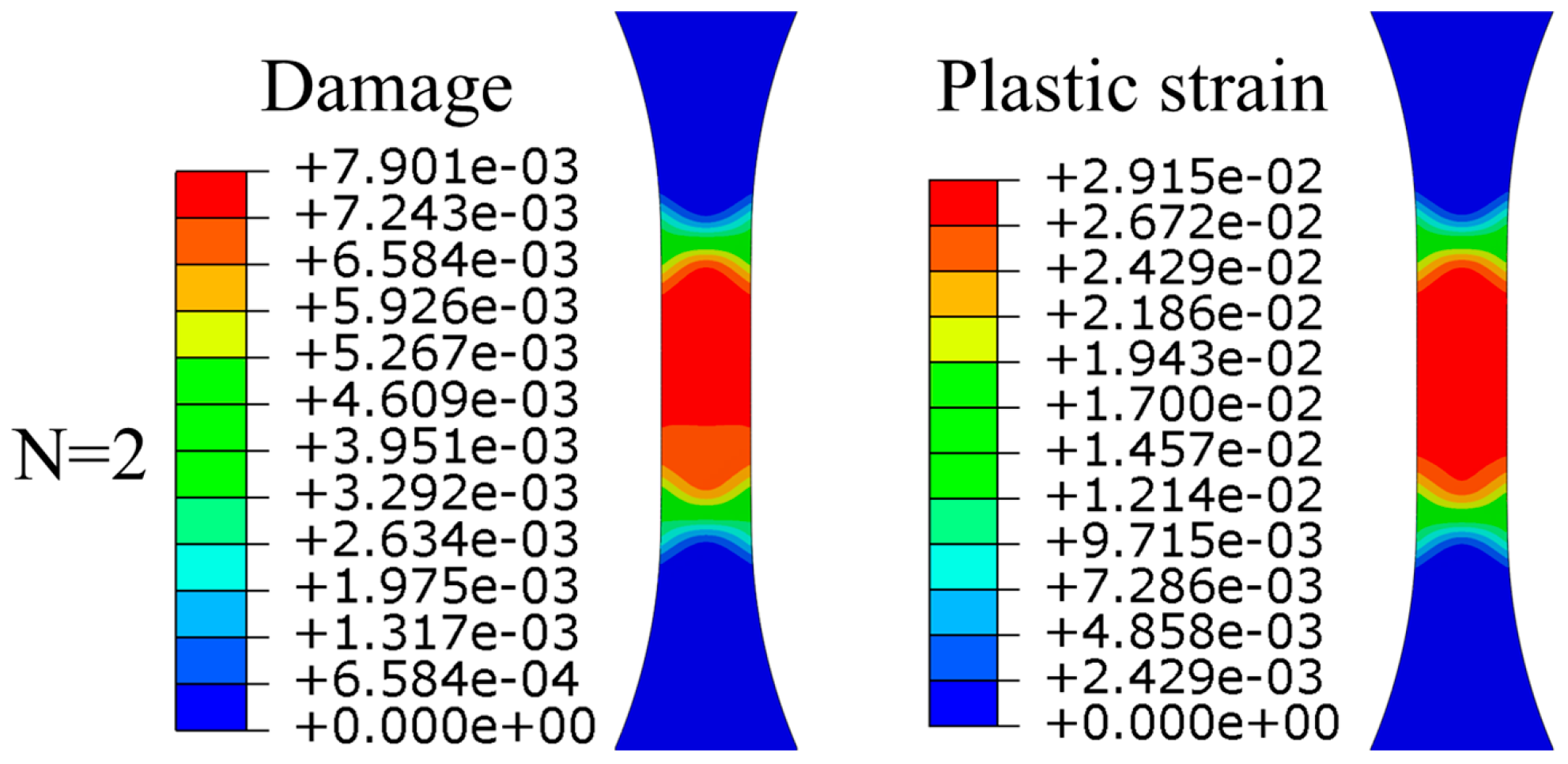

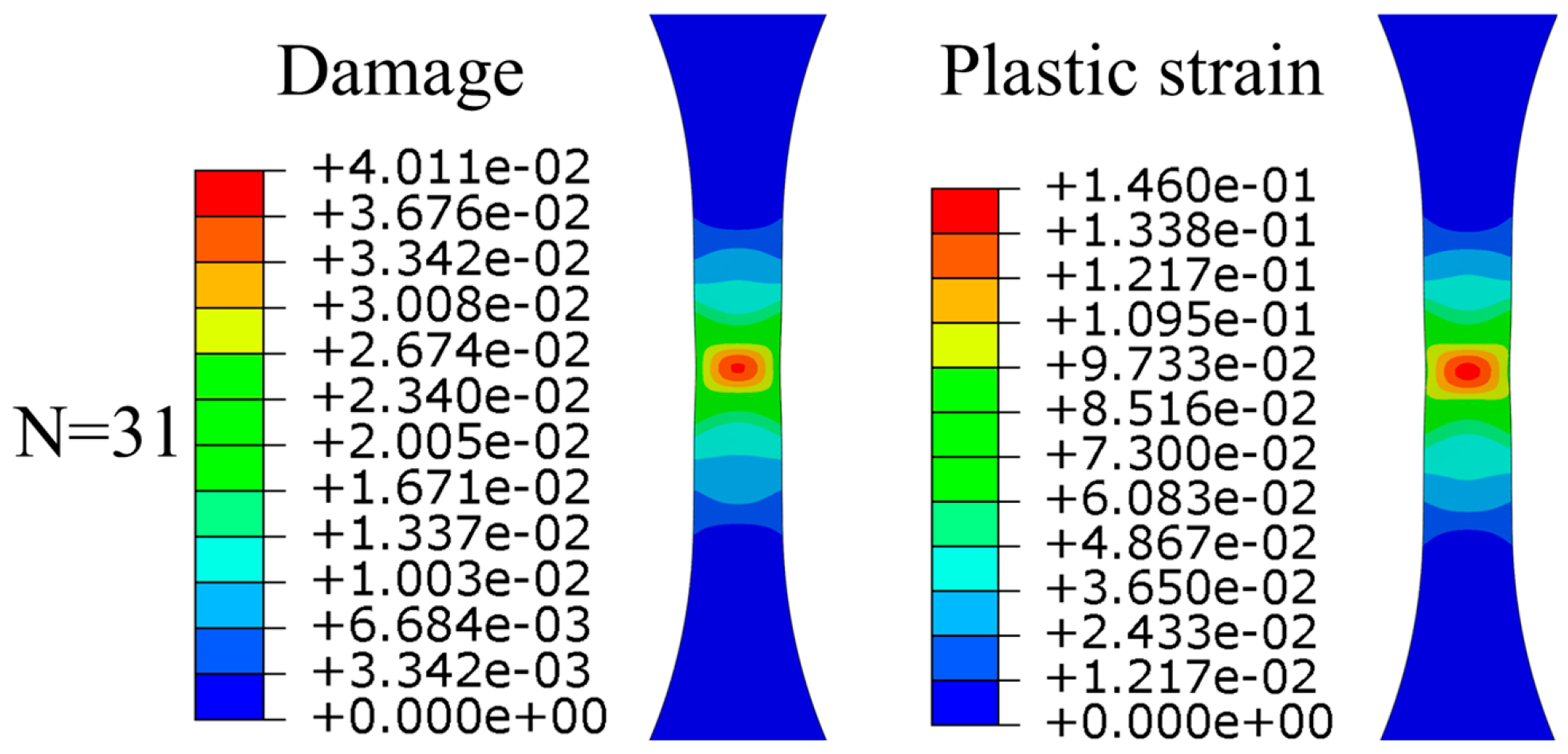

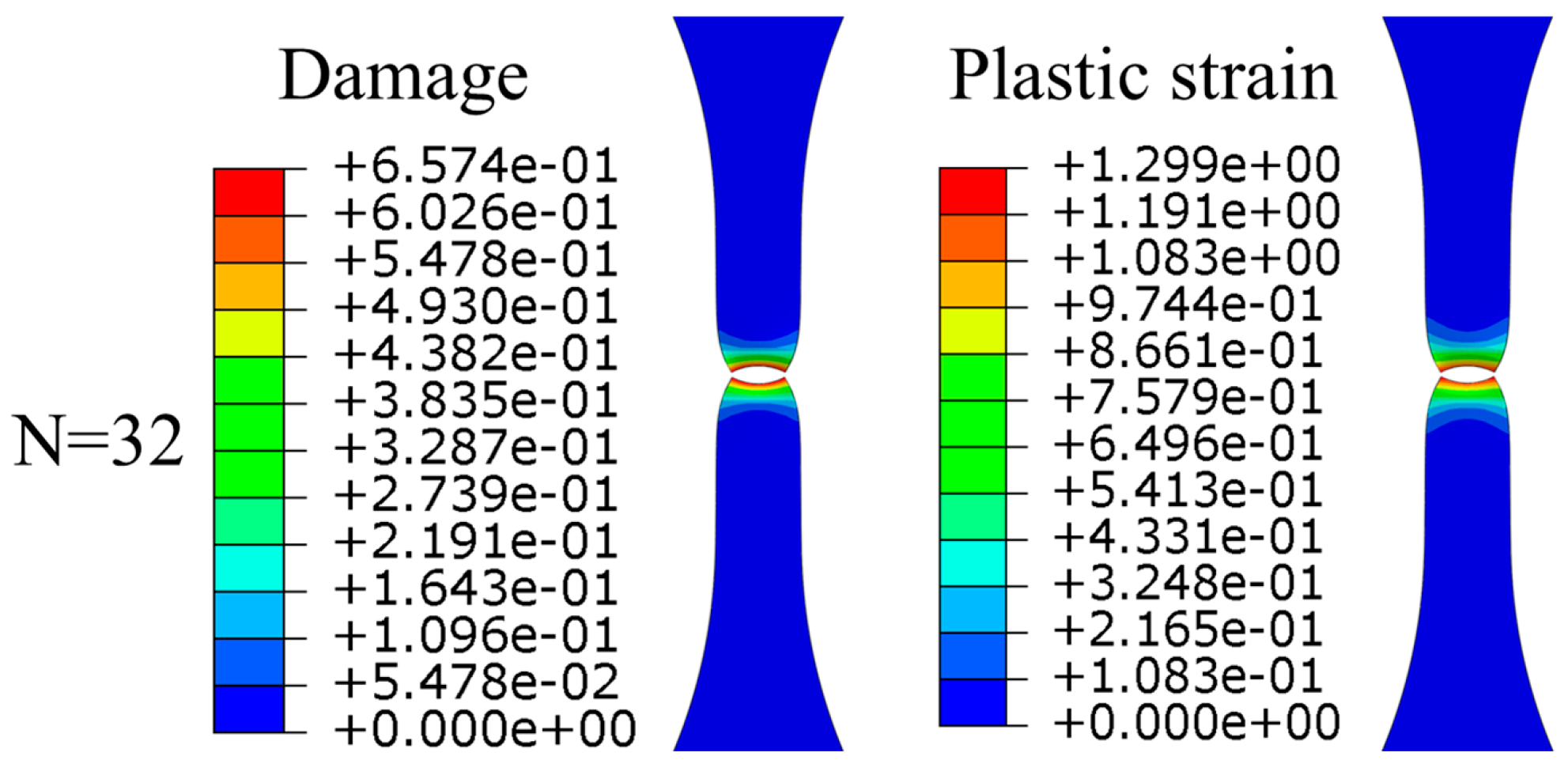

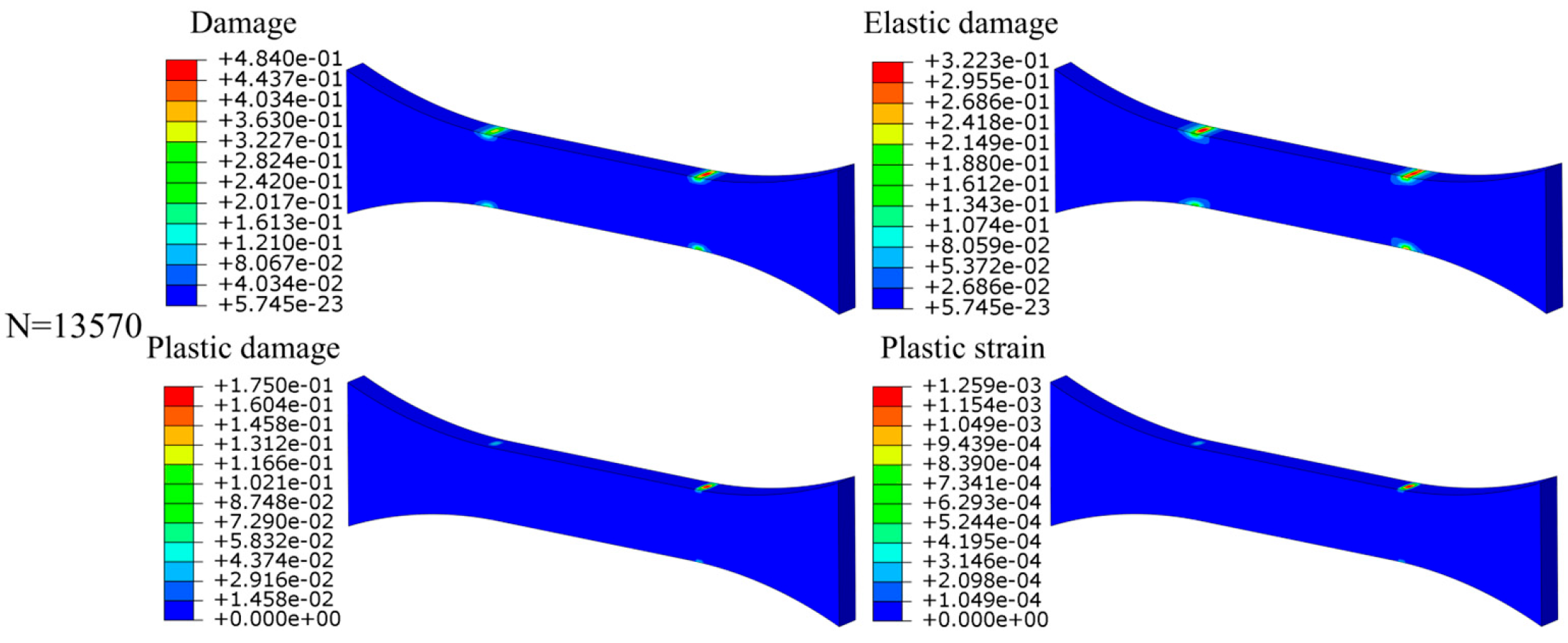

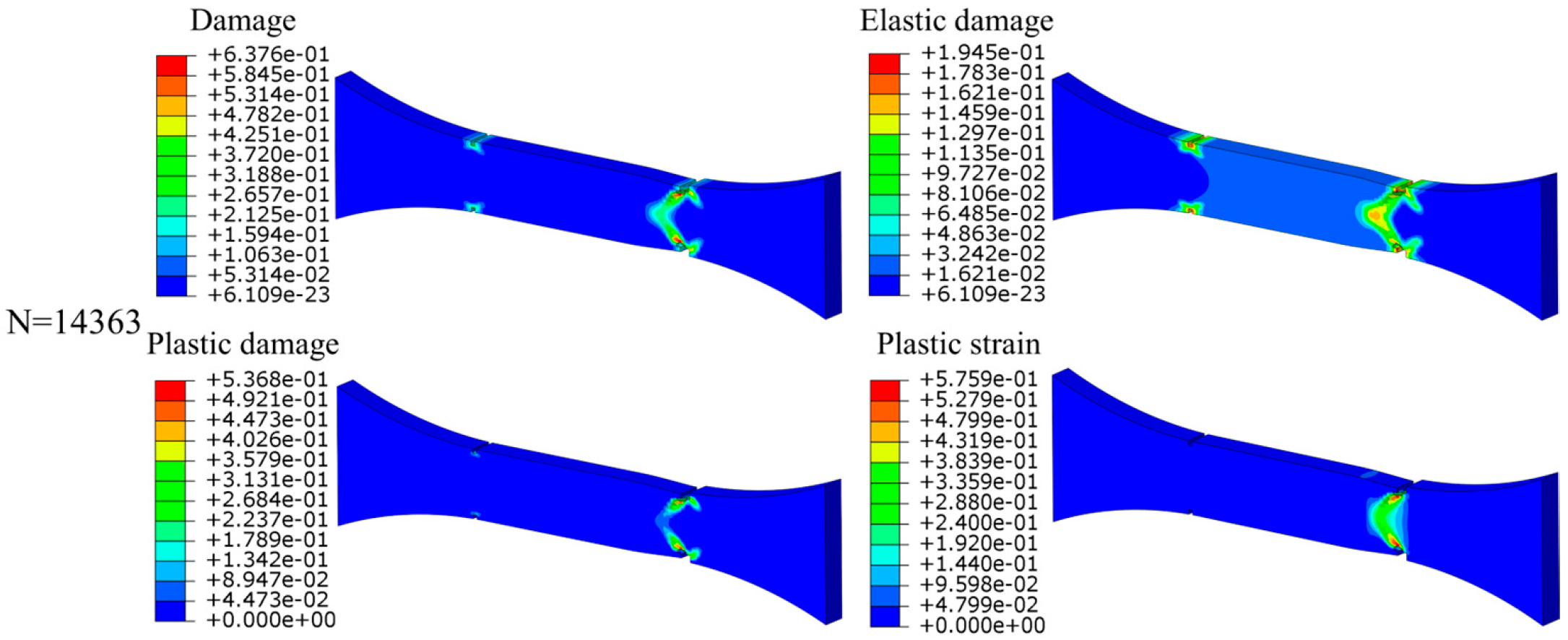

4.4.1. Damage Evolution Under Stress-Controlled Post-Yield Cyclic Loading

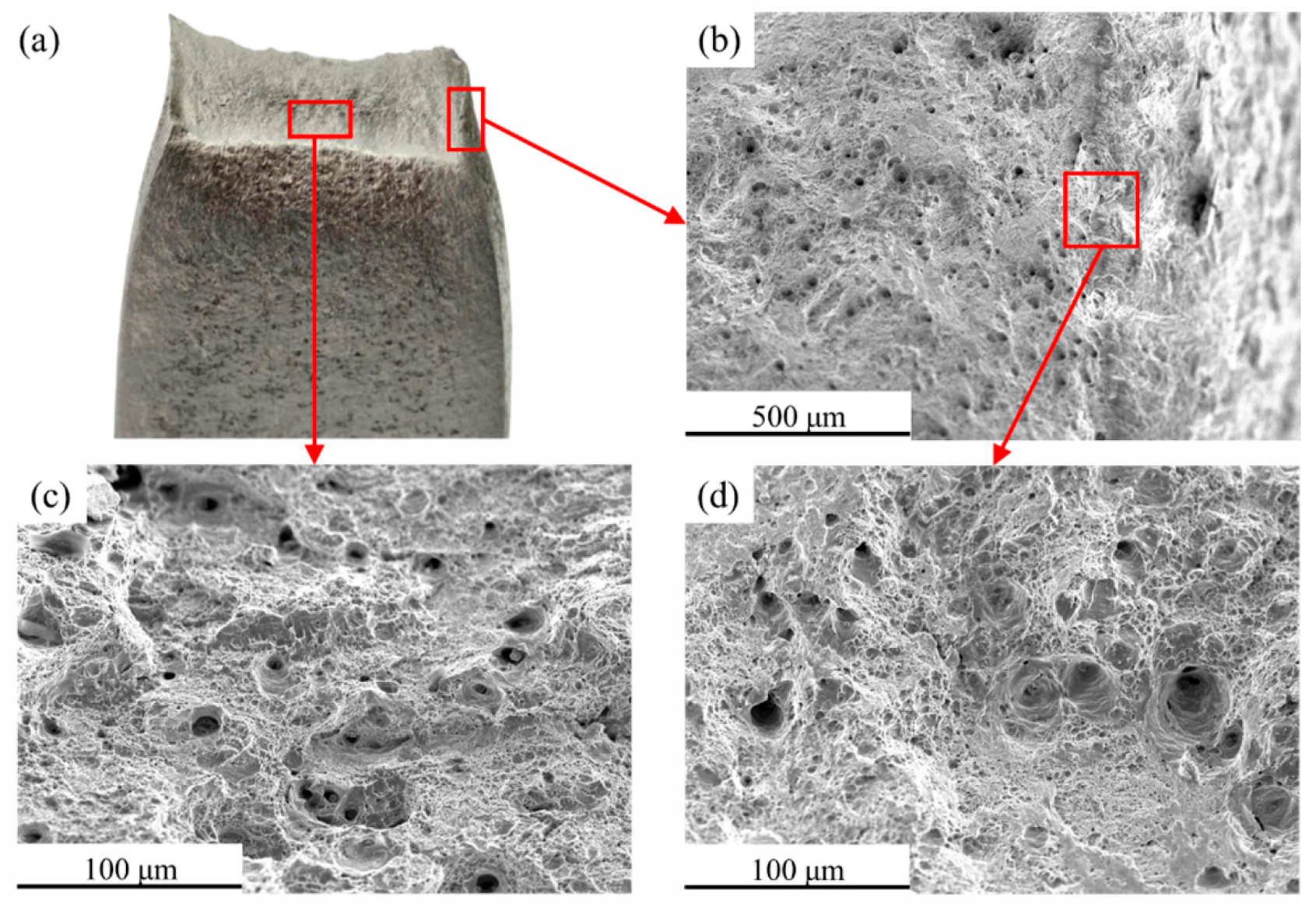

4.4.2. Damage Evolution Under Cyclic Loading Below Yield

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Romero, A.; Caminero, M.A.; García-Plaza, E.; Núñez, P.J.; Chacón, J.M.; Rodríguez, G.P.; Cañadilla, A.; Martínez, J.L. Mechanical and metrological characterisation of 17-4PH stainless steel structures processed by material extrusion additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 38, 1699–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hebert, R.J.; Aindow, M. Effect of laser scan length on the microstructure of additively manufactured 17-4PH stainless steel thin-walled parts. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Ma, A.; Xu, X.; Zhang, W. An investigation of fretting fatigue behavior and mechanism in 17-4PH stainless steel with gradient structure produced by an ultrasonic surface rolling process. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 131, 105340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, B.; Pramanik, B.; Kudzal, A.; Taggart-Scarff, J. High strain rate compressive deformation behavior of an additively manufactured stainless steel. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 24, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeli, G.; Auger, M.A.; Wilford, K.; Smith, G.D.W.; Bagot, P.A.J.; Moody, M.P. Sequential nucleation of phases in a 17-4PH steel: Microstructural characterisation and mechanical properties. Acta Mater. 2017, 125, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Meng, Q.; Fan, W.; Gu, W.; Wan, J.; Li, Q. Vibration characteristics and life prediction of last stage blade in steam turbine Based on wet steam model. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 159, 108127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Xu, B.; Liao, T.; Yin, C.; Tan, Z. Application of local-feature-based 3-D point cloud stitching method of low-overlap point cloud to aero-engine blade measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1008913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Application of ductile fracture model for the prediction of low cycle fatigue in structural steel. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2023, 289, 109469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xie, X.; Cheng, C.; Tian, Q. A modified Coffin-Manson model for ultra-low cycle fatigue fracture of structural steels considering the effect of stress triaxiality. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2020, 237, 107223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, R.J.; O’Donoghue, P.E.; Leen, S.B. Experimental characterisation and computational modelling for cyclic elastic-plastic constitutive behaviour and fatigue damage of X100Q for steel catenary risers. Int. J. Fatigue 2018, 116, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.; De Jesus, A.; Fernandes, A.A. A new ultra-low cycle fatigue model applied to the X60 piping steel. Int. J. Fatigue 2016, 93, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lin, J.; Zhuge, H.; Xie, X.; Cheng, C. Ultra-low cycle fatigue fracture initiation life evaluation of thick-walled steel bridge piers with microscopic damage index under bidirectional cyclic loading. Structures 2022, 43, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, M.; Choi, Y.; Bai, Y. A unified material model for multiaxial ductile fracture and extremely low cycle fatigue of Inconel 718. Int. J. Fatigue 2017, 96, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, Z.J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.F. Extremely-low-cycle fatigue behaviors of Cu and Cu–Al alloys: Damage mechanisms and life prediction. Acta Mater. 2015, 83, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yue, J.; Wu, X.; Lei, J.; Fang, X. A damage coupled elasto-plastic constitutive model of marine high-strength steels under low cycle fatigue loadings. Int. J. Pres. Ves. Pip. 2023, 205, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, R.A.; O’Donoghue, P.E.; Leen, S.B. A physically-based constitutive model for high temperature microstructural degradation under cyclic deformation. Int. J. Fatigue 2017, 100, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauzay, M.; Fournier, B.; Mottot, M.; Pineau, A.; Monnet, I. Cyclic softening of martensitic steels at high temperature—Experiments and physically based modelling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 483–484, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Kang, L. A damage index-based evaluation method for predicting the ductile crack initiation in steel structures. J. Earthq. Eng. 2012, 16, 623–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateishi, K.; Hanji, T.; Minami, K. A prediction model for extremely low cycle fatigue strength of structural steel. Int. J. Fatigue 2007, 29, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L. A unified expression for low cycle fatigue and extremely low cycle fatigue and its implication for monotonic loading. Int. J. Fatigue 2008, 30, 1691–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, G.; Han, J.; Wang, S.; He, W.; Zhu, S. An enhanced Hosford–Coulomb fracture model for predicting ductile fracture under a wide range of stress states. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 312, 110635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Shen, W.; Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, C.; Xue, F. An uncoupled ductile fracture criterion for a wide range of stress states in sheet metal forming failure prediction. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 310, 110464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambirajan, T.; Kumar, P.C.A.; Aggarwal, S.; Gurudutt, A. Uncoupled fracture model for E250, E350, and E450 grades of structural steel under monotonic loading. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2023, 292, 109638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhu, T. Ductile fracture of X80 pipeline steel over a wide range of stress triaxialities and Lode angles. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2023, 289, 109470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Zhang, P.; Chen, B.; Li, Y.; Xing, J. A new ductile fracture model for Q460C high-strength structural steel under monotonic loading: Experimental and numerical investigation. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2023, 288, 109358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Chen, L.; Clausmeyer, T.; Tekkaya, A.E.; Yoon, J.W. Modeling of ductile fracture from shear to balanced biaxial tension for sheet metals. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2017, 112, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Yoon, J.W.; Huh, H. Modeling of shear ductile fracture considering a changeable cut-off value for stress triaxiality. Int. J. Plast. 2014, 54, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.S.A.; Kueh, A.B.H.; Tamin, M.N.; Kim, J.J.; Kadir, M.A.A.; Yahaya, N.; Noor, N.M. Water–Cement Ratio on High-Cycle Fatigue in the Theory of Critical Distances of Plain Concrete, Iranian Journal of Science and Technology. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2022, 46, 4281–4290. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Badshah, S.; Koloor, S.R.; Amjad, M.; Khalil, S.; Tamin, N. Cumulative fretting fatigue damage model for steel wire ropes. Fatigue Fract. Eng. M. 2024, 47, 1656–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastgerdi, J.N.; Jaberi, O.; Remes, H.; Lehto, P.; Toudeshky, H.H.; Kuva, J. Fatigue damage process of additively manufactured 316 L steel using X-ray computed tomography imaging. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 70, 103559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, R.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Xu, W. Characterization of uncoupled ductile fracture criteria for 0Cr17Ni4Cu4Nb stainless steel under different stress states. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 5985–6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, H.W. Plastic instability under plane stress. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1952, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voce, E. The relationship between stress and strain for homogeneous deformation. J. Inst. Met. 1948, 74, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y.; Wierzbicki, T. On fracture locus in the equivalent strain and stress triaxiality space. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2004, 46, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Li, S.; Gao, Z. A continuum damage mechanics model for high cycle fatigue. Int. J. Fatigue 1998, 20, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | C | Cr | Ni | Cu | Si | Mn | Nb | Ti | P | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (wt%) | 0.05 | 15.54 | 4.33 | 3.51 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.028 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Specimen | Average Stress Triaxility | Average Lode Parameter | Lou-Yoon | Enhanced-Lou-Yoon | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error | Error | ||||||

| FS | 0.0929 | −0.2015 | 0.6989 | 0.7064 | 1.11% | 0.7064 | 1.11% |

| FCH | 0.4734 | −0.7297 | 1.0838 | 0.8184 | 24.86% | 0.7301 | 32.64% |

| SRB | 0.5861 | −0.9964 | 0.9328 | 0.9781 | 4.85% | 0.8413 | 9.81% |

| FNT | 0.6726 | −0.4865 | 0.8336 | 0.5917 | 28.57% | 0.6381 | 23.45% |

| NRBR3 | 1.1040 | −0.9954 | 0.6244 | 0.7145 | 14.43% | 0.5370 | 14.00% |

| NRBR1.5 | 1.4685 | −0.9955 | 0.3963 | 0.6017 | 51.82% | 0.3961 | 0.05% |

| Average Error | 20.94% | 13.51% | |||||

| 1.4 | 0.75 | 5 | 0.0025 | 0.001258 | 2950 | 245 |

| Group | Load/N | Stress/MPa | Cycles to Failure | Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Simulation | ||||

| ① | 25,050 | 1043.75 | 38 | 32 | 15.8% |

| ② | 24,795 | 1033.13 | 117 | 93 | 20.5% |

| ③ | 24,220 | 1009.17 | 625 | 546 | 12.6% |

| ④ | 20,800 | 866.67 | 9298 | 9990 | 7.4% |

| ⑤ | 20,600 | 858.33 | 11,689 | 13,570 | 16.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, X.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Pan, Y.; Wu, H.; Chen, X. A Damage Model for Predicting Fatigue Life of 0Cr17Ni4Cu4Nb Stainless Steel Under Near-Yield Stress-Controlled Cyclic Loading. Coatings 2025, 15, 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15111318

Cheng X, Wang R, Li Y, Zhou Z, Pan Y, Wu H, Chen X. A Damage Model for Predicting Fatigue Life of 0Cr17Ni4Cu4Nb Stainless Steel Under Near-Yield Stress-Controlled Cyclic Loading. Coatings. 2025; 15(11):1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15111318

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Xiang, Ruomin Wang, Yong Li, Zhongkang Zhou, Yingfeng Pan, He Wu, and Xiaolei Chen. 2025. "A Damage Model for Predicting Fatigue Life of 0Cr17Ni4Cu4Nb Stainless Steel Under Near-Yield Stress-Controlled Cyclic Loading" Coatings 15, no. 11: 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15111318

APA StyleCheng, X., Wang, R., Li, Y., Zhou, Z., Pan, Y., Wu, H., & Chen, X. (2025). A Damage Model for Predicting Fatigue Life of 0Cr17Ni4Cu4Nb Stainless Steel Under Near-Yield Stress-Controlled Cyclic Loading. Coatings, 15(11), 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15111318