1. Introduction

Orthopedic implants have transformed the clinical management of trauma, degenerative disease and congenital deformities. However, implant-associated infection (IAI) [

1,

2] persists as a challenging complication that can jeopardize osseointegration, prolong hospitalization, and necessitate costly revision procedures. Biofilm-forming pathogens such as

Staphylococcus aureus and opportunistic Gram-negative species (e.g.,

Escherichia coli) colonize abiotic surfaces and acquire tolerance to antibiotics, reducing therapeutic options once infection is established [

3]. This clinical reality has driven interest in surface engineering strategies that endow implant materials with an intrinsic, long-lasting antibacterial function while preserving the biological performance needed for bone integration.

Among antibacterial agents, silver (Ag) is notable for its broad-spectrum activity, lack of specific bacterial target binding, and effectiveness against antibiotic-resistant strains [

4]. Nonetheless, translating Ag into load-bearing implant coatings presents two recurring obstacles. First, the mechanical robustness of particulate or polymer-bound Ag systems is often inadequate for long-term service in vivo, where interfaces can be challenged by micromotion and interfacial shear. Second, uncontrolled or excessive Ag

+ release may cause local cytotoxicity and interfere with osteogenic processes. Thin-film approaches address these constraints by immobilizing Ag within a dense, adherent metallic layer whose release kinetics are governed by surface chemistry and microstructure rather than particulate detachment [

3,

5].

High power impulse magnetron sputtering (HiPIMS) [

6] has emerged as a particularly attractive method for fabricating such layers. Compared to direct-current magnetron sputtering (DCMS), HiPIMS pulses yield a high degree of target material ionization and high ion energies at the growing surface, enabling densification, improved texture control, and strong film–substrate adhesion at modest substrate temperatures [

7,

8]. These attributes are advantageous for Ti implants, which are commonly used in orthopedic devices and must retain favorable biomechanical and surface properties. With HiPIMS, very short deposition times can yield continuous Ag coverage with a fine-grained microstructure, while the ion-assisted growth mode enhances interfacial quality [

9].

Building on these considerations, the present work investigates Ag thin films deposited onto Ti by HiPIMS, focusing specifically on antibacterial efficacy and osteoblast cytocompatibility. It is anticipated that (i) HiPIMS produces continuous, crystalline Ag films at short deposition times with robust adhesion; (ii) even ultrathin films provide strong antibacterial effects through controlled, low-level Ag

+ release; and (iii) the resulting coatings are cytocompatible with osteoblastic cells [

10]. The study aims to provide a coherent data set that supports the use of HiPIMS-Ag as a surface-engineered active antibacterial solution for Ti implants.

2. Materials and Methods

Commercially pure Ti substrates, prepared in two sizes (50 mm × 50 mm × 1 mm for antibacterial testing and 25 mm × 25 mm × 1 mm for osteoblast compatibility testing), were all subjected to the same cleaning procedure. Each specimen was ultrasonically cleaned in acetone, ethanol and deionized water, followed by air drying. Immediately prior to deposition, specimens received an argon plasma pre-treatment to remove adventitious surface contaminants and to enhance interfacial bonding. Ag films were deposited using a HiPIMS power supply coupled to a planar Ag target (335 mm × 114 mm). Power parameters were chosen to achieve a high ionized fraction of sputtered species to facilitate a fine-grained microstructure and strong film adhesion [

9]. Substrate table was without additional heating.

Figure 1a shows the coating chamber inside with Ag target and Ti substrates attached onto rotation substrate holder and

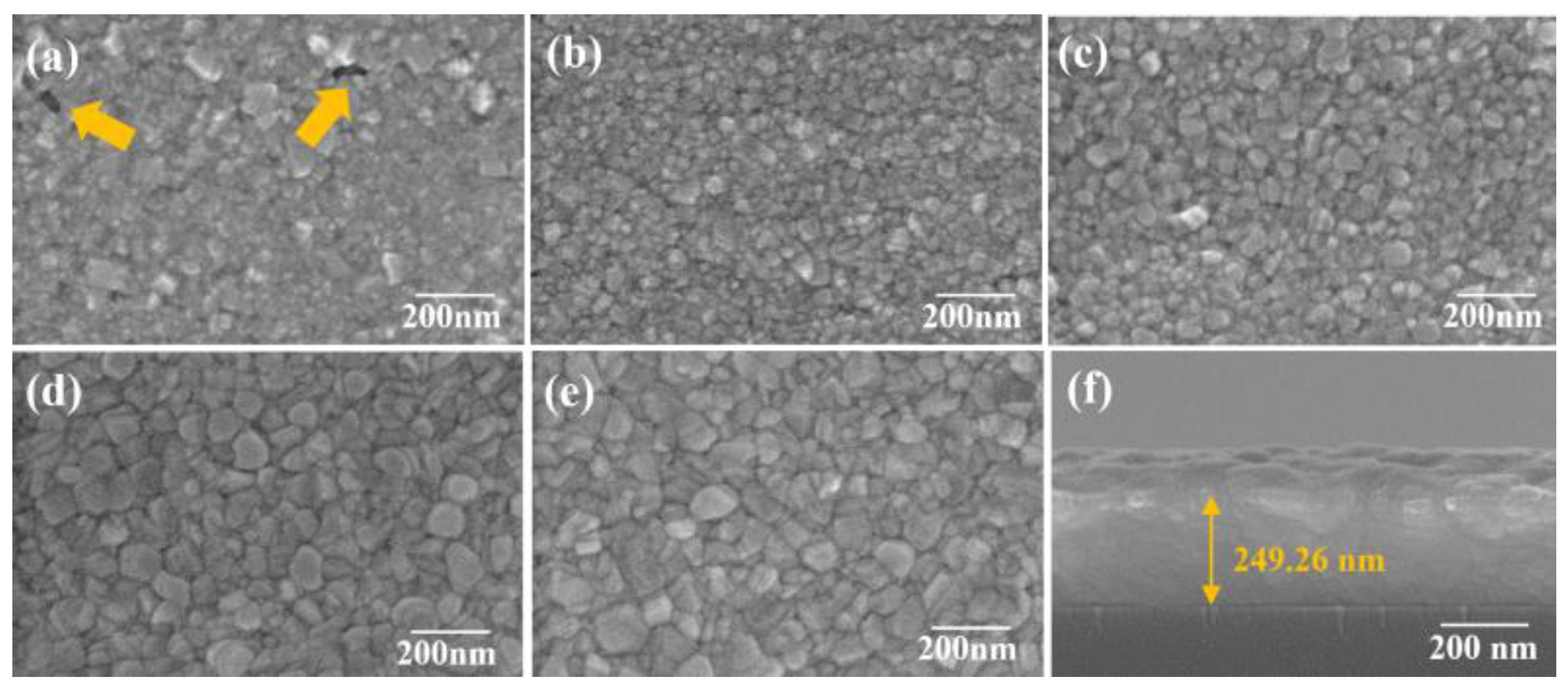

Figure 1b shows the target peak voltage and the responded peak current. Deposition time was systematically varied from a few seconds to several minutes to tune film thickness over the ultrathin to sub-hundred-nanometer regime. Process conditions (pressure, target–substrate distance, duty cycle) were held constant for parametric comparisons. The overall goal was to establish the minimum deposition time needed for continuous Ag coverage with satisfactory adhesion.

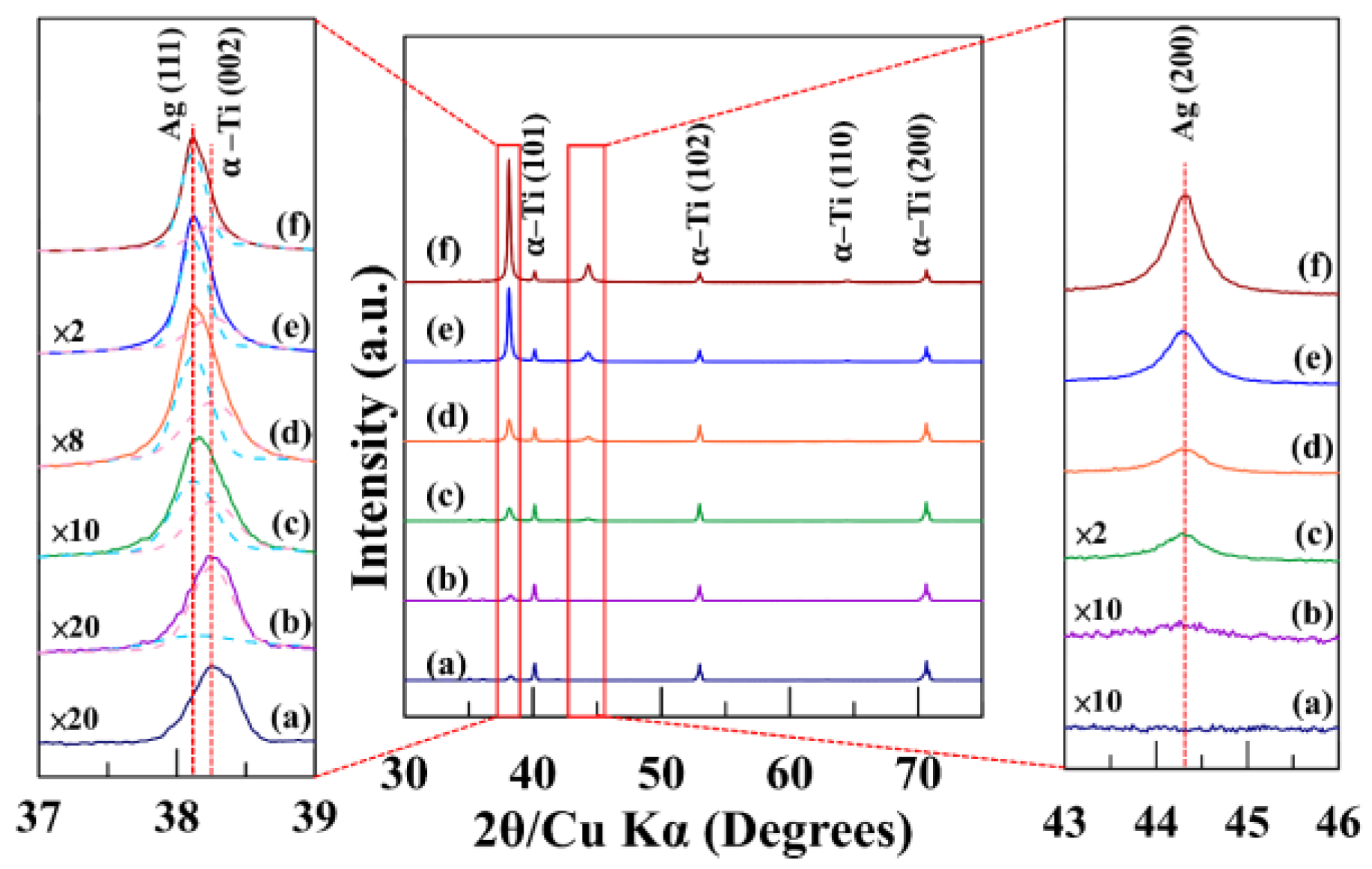

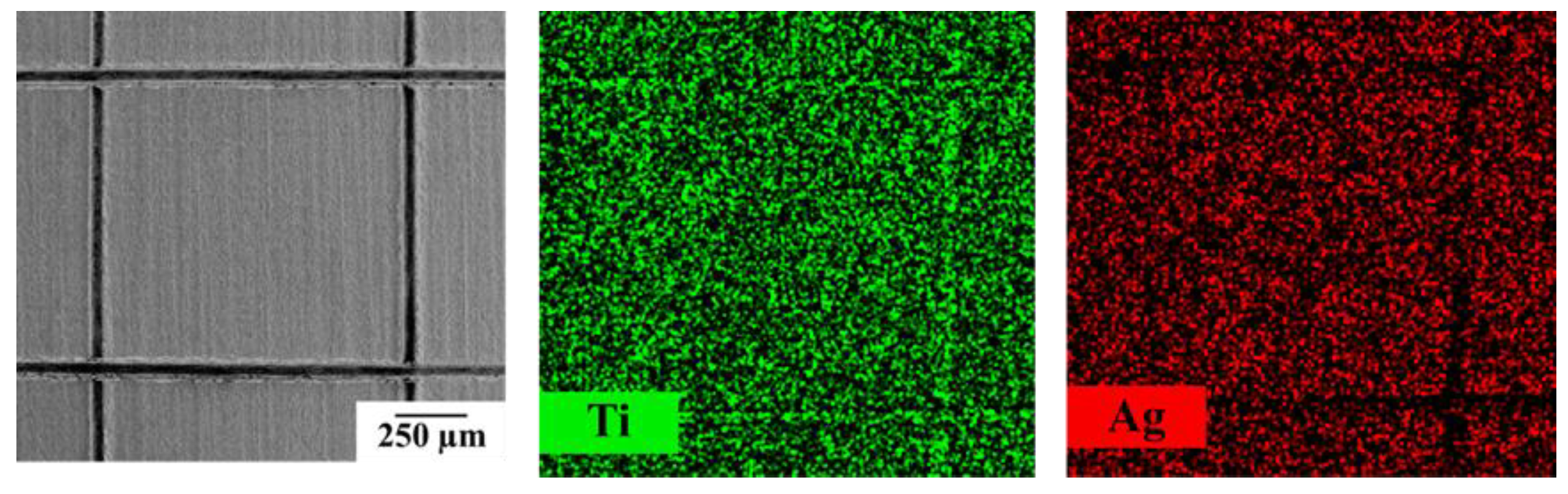

Plan-view and cross-sectional morphologies were examined by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). Additionally, the cross-sectional image was also used to estimate film thickness and infer the growth rate from thickness–time relationships. X-ray diffractometry (XRD) was used to assess crystallinity and texture.

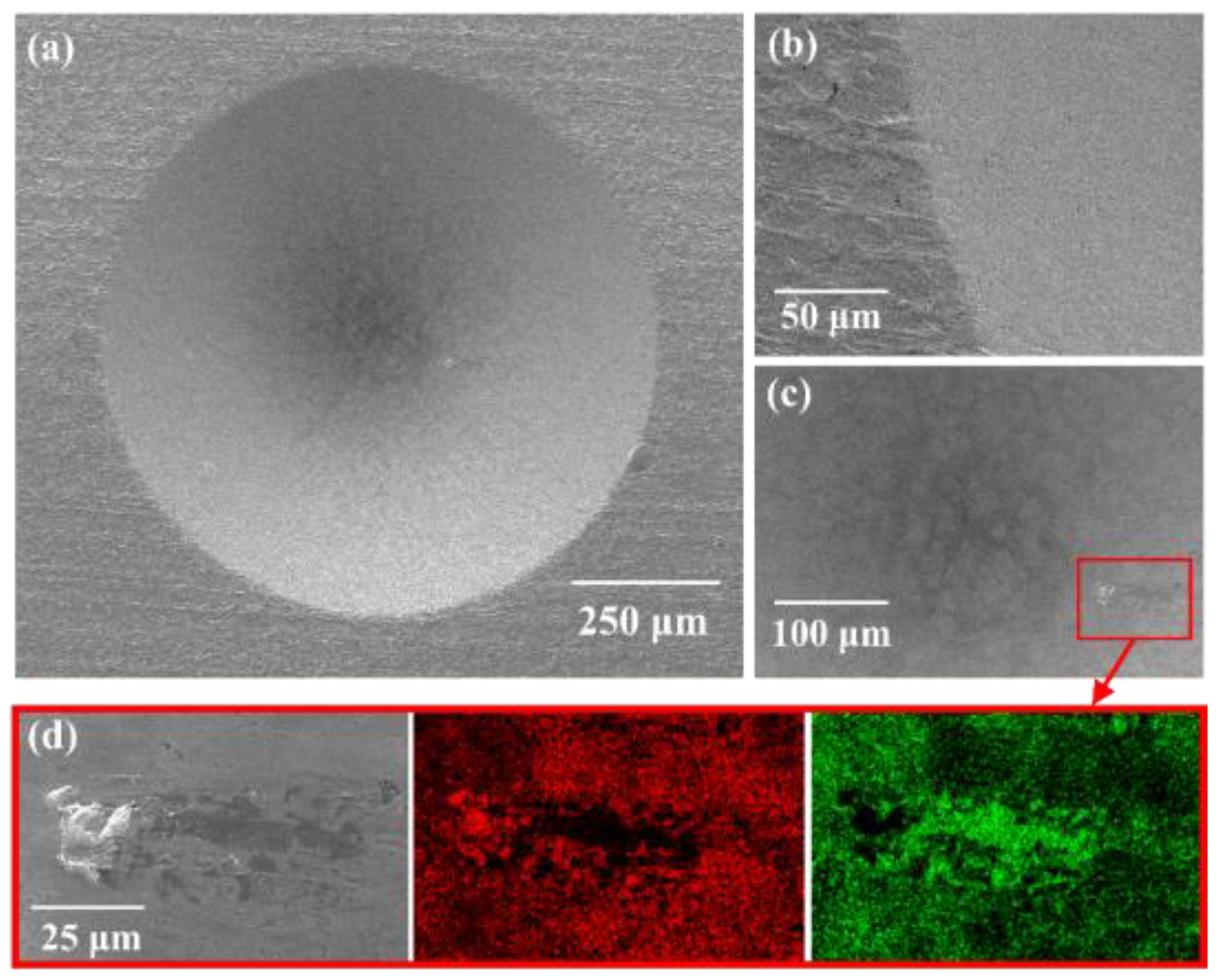

Interfacial adhesion was quantified by ASTM D3359-02 cross-cut tape testing [

11] using standard procedures and a rating scale from 0B to 5B, where 5B indicates no detachment along the scribed lattice. Complementary Daimler-Benz Rockwell-C indentation (VDI 3198) [

12] was performed to evaluate cohesive/adhesive failures surrounding the indentation imprint (classifications HF1–HF6).

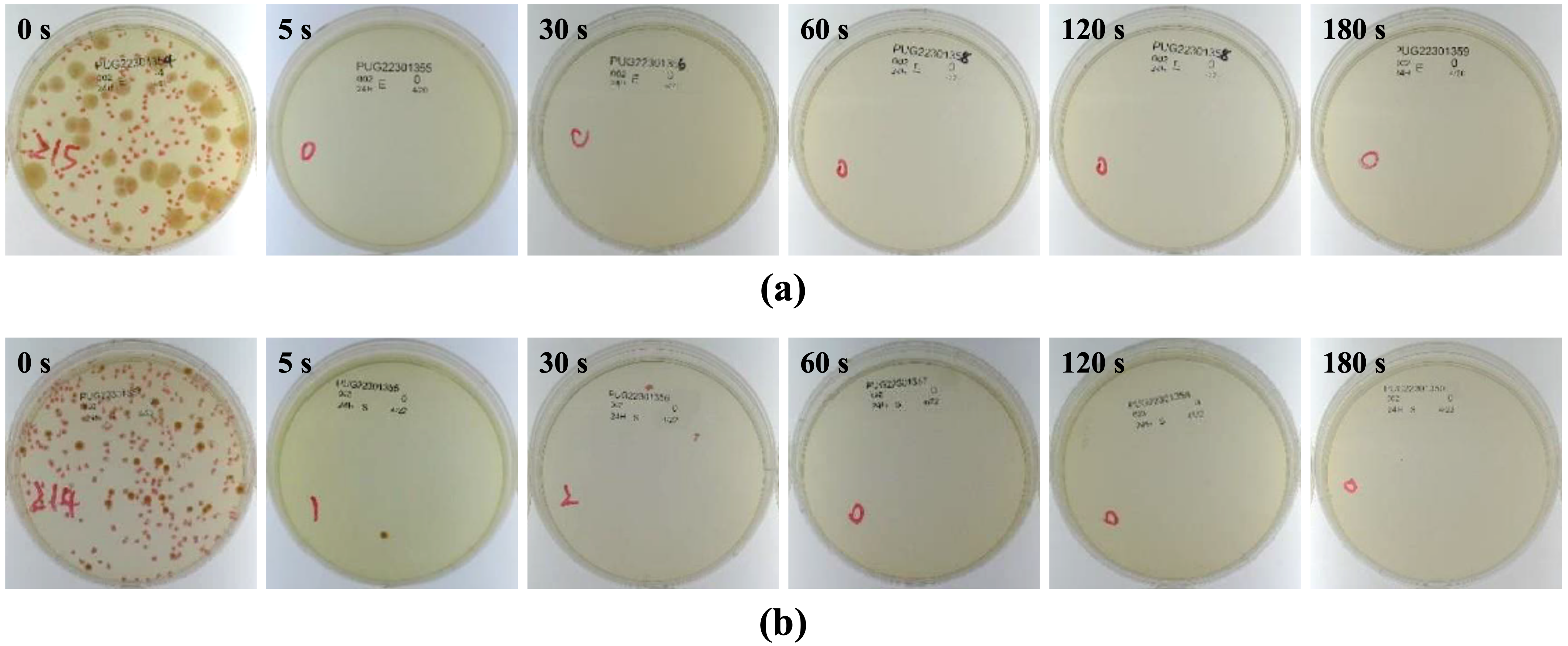

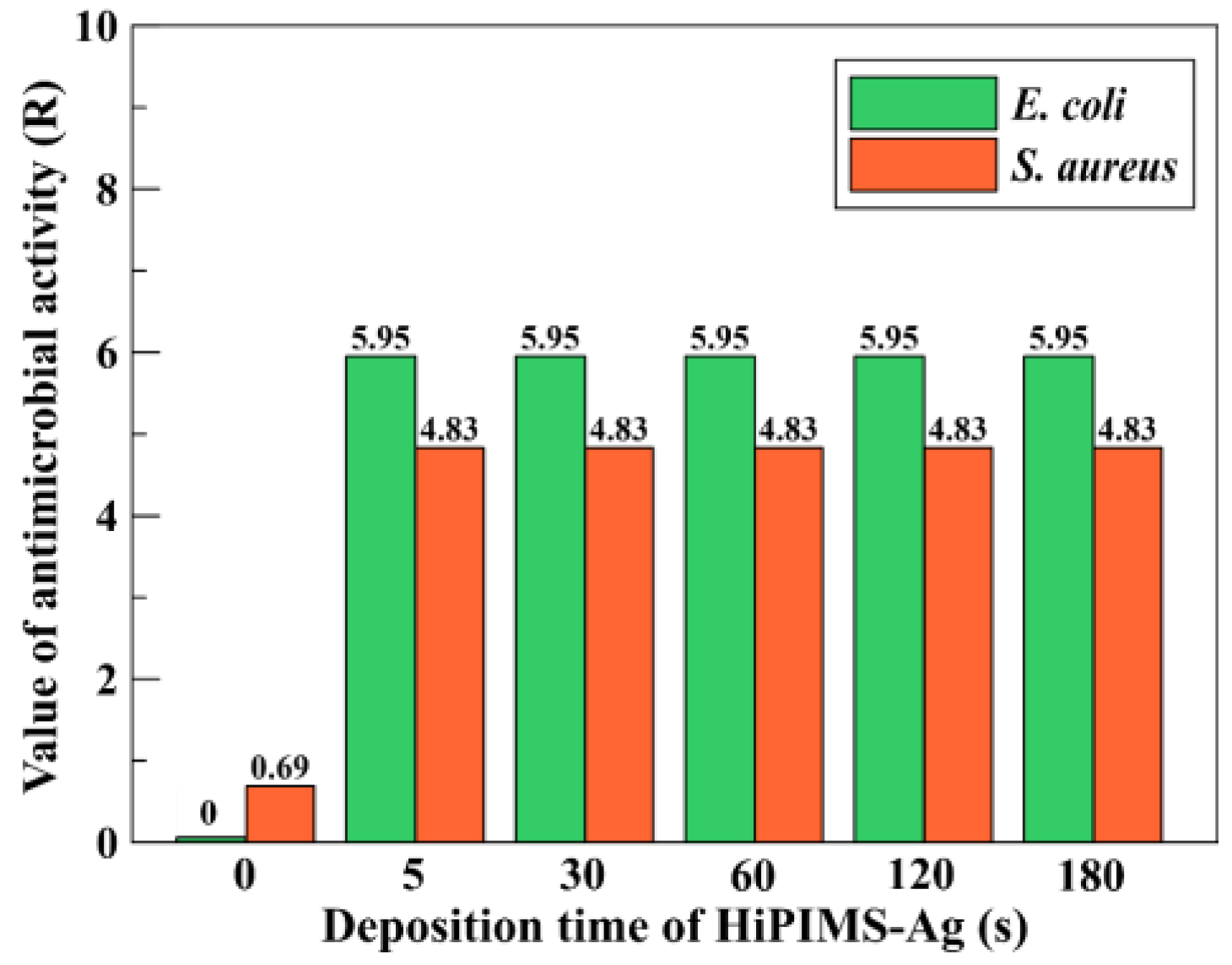

Antibacterial activity was evaluated against

Escherichia coli and

Staphylococcus aureus according to JIS Z 2801:2010 [

13]. Briefly, sterilized specimens were inoculated with a defined bacterial suspension and incubated under controlled temperature and humidity. After exposure, non-adherent bacteria were gently rinsed off and surface-associated bacteria were recovered and enumerated on agar plates. Antibacterial activity values were calculated relative to uncoated Ti controls using established protocols. Each condition included multiple technical replicates and at least three independent experiments. Colony-forming units (CFU) per specimen were calculated as N = C × D × V, where C is the mean colony count of duplicate plates, D is the dilution factor, and V is the recovery volume (mL; here, 9.76 mL). Antibacterial activity was expressed as R = log

10(N

B/N

C) equivalent to [log

10(N

B/N

A) − log

10(N

C/N

A)], where N

A is the CFU for Group A (titanium, immediate rinse), N

B is the CFU for Group B (titanium after 24 h), and N

C is the CFU for Group C (HiPIMS-Ag after 24 h). In accordance with the JIS criterion, specimens were considered antibacterial when R > 2.0.

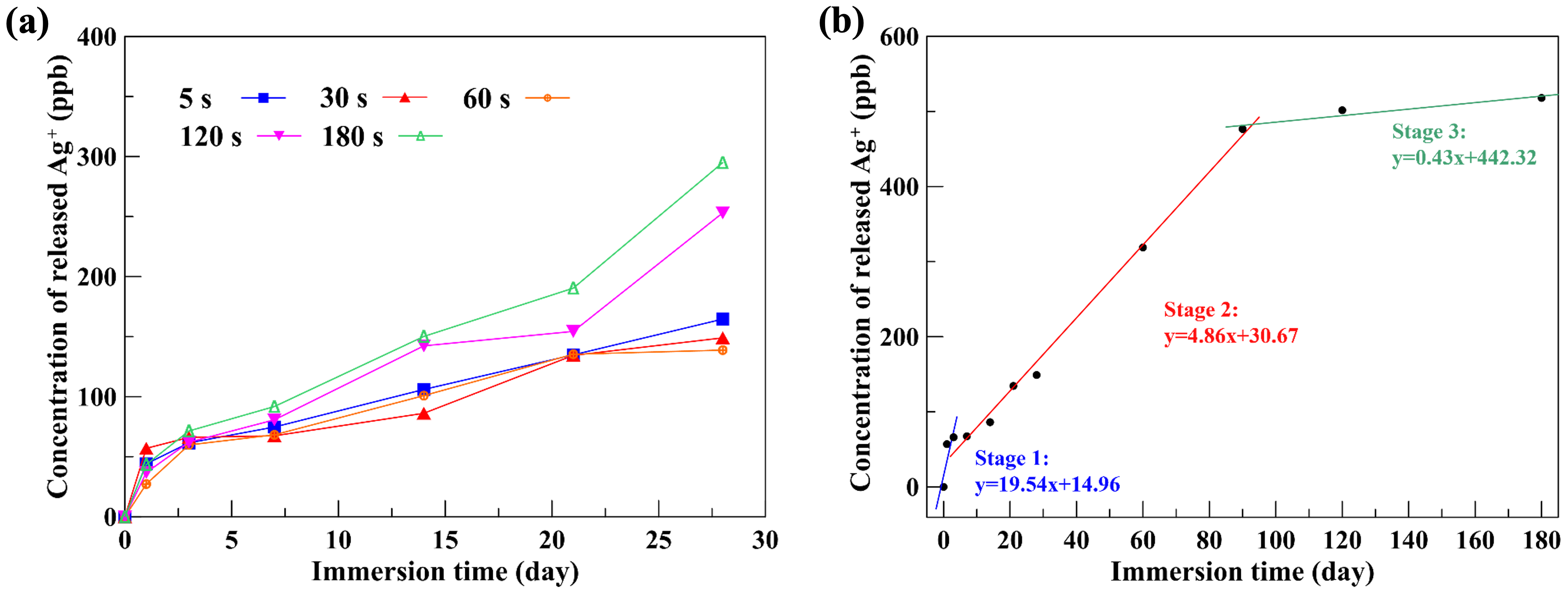

The HiPIMS-Ag thin-film specimens were immersed in PBS to simulate the silver-ion release behavior after implantation. Potential correlations between antibacterial performance and Ag+ availability, aliquots were collected at specified intervals. Ag+ concentrations were quantified using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

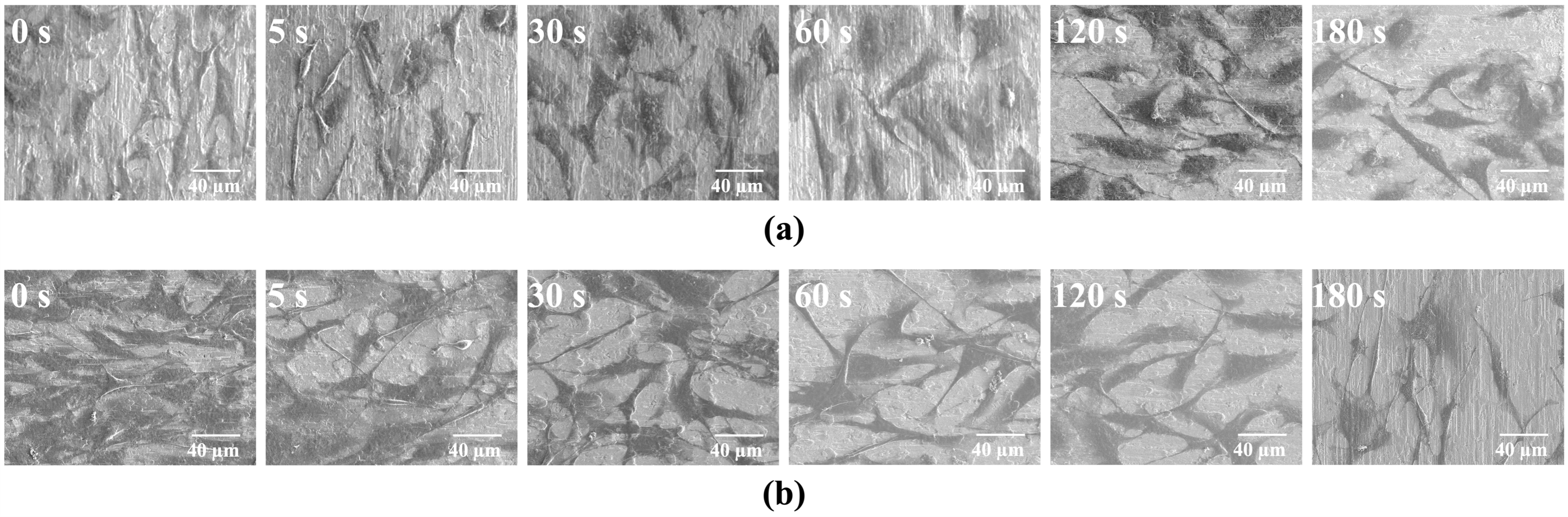

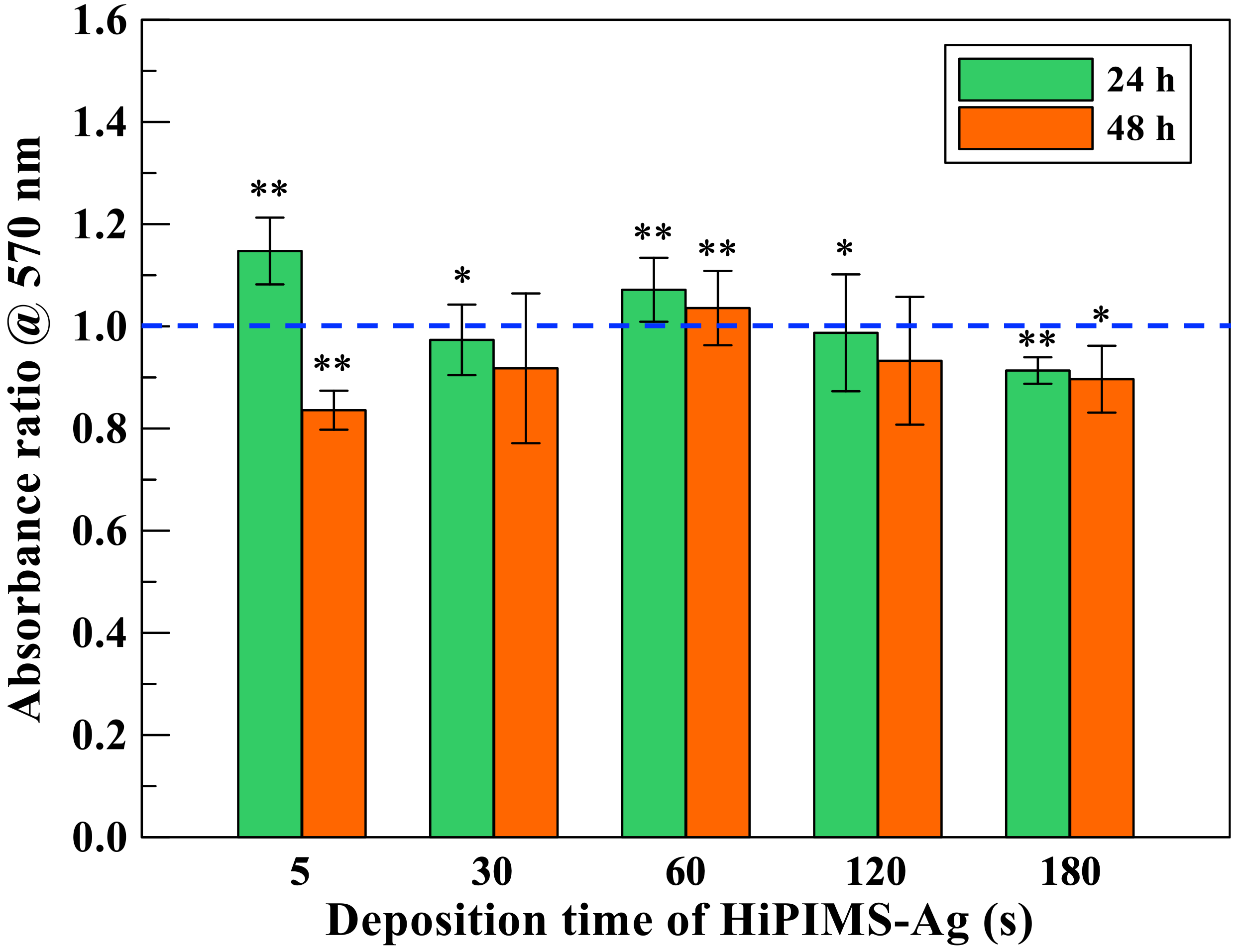

MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells were used as a model to assess host compatibility. Cells were seeded onto coated and uncoated Ti substrates and cultured under standard conditions. Early adhesion and spreading were visualized microscopically at 4 h and 24 h. Cell proliferation and metabolic activity were evaluated at later time points using common viability assays.

4. Discussion

The present results demonstrate that HiPIMS can translate silver’s well-established antibacterial properties into a form of thin-film that is mechanically robust and biologically acceptable for titanium implants. Several aspects of the data merit discussion. First, the rapid onset of crystallinity and film continuity at short deposition times reflects the high degree of ionization and energetic bombardment characteristic of HiPIMS [

6]. In contrast to conventional DC or pulsed-DC magnetron sputter deposition [

14,

15], the highly ionized plasma in HiPIMS generates energetic metal ions that bombard the substrate surface, providing additional energy to adatoms and enhancing their surface mobility. The increased adatom mobility promotes lateral diffusion and densification of the growing film, thereby suppressing the formation of columnar porosity typically observed in low-energy sputter growth [

8]. This ion-assisted densification not only results in a fine-grained, compact microstructure but also reinforces interfacial adhesion. Such microstructural integrity is consistent with the excellent 5B cross-cut rating and the absence of delamination around the Rockwell-C imprints [

9]. The combination of strong adhesion and dense microstructure is expected to ensure long-term stability under physiological conditions. In clinical practice, modular junctions and fixation interfaces experience micromotion and shear. Coatings that detach or crack under such loads can generate debris and expose bare substrate regions that favor biofilm formation. By contrast, HiPIMS-Ag’s interfacial robustness suggests resilience against these mechanical challenges. Although full in vivo testing and mechanical wear simulations (e.g., pin-on-disk or fretting) were beyond the present scope, the adhesion metrics provide encouraging proxies for durability.

Second, the antibacterial efficacy observed for ultrathin (~7 nm) films highlights the importance of interfacial chemistry and surface-mediated ion exchange rather than bulk silver inventory [

4]. In other words, a small areal reservoir of Ag—when presented as a continuous film with high surface quality—can yield sufficient Ag

+ flux to challenge planktonic bacteria and early colonizers without exceeding levels associated with cytotoxic effects [

4,

16,

17,

18]. Quantitatively, according to previous studies [

16], the minimum effective concentration of Ag

+ required to exhibit antibacterial activity is approximately 0.1 ppb. In the present work, all HiPIMS-Ag film specimens released Ag

+ concentrations exceeding this antibacterial threshold, which explains why every coating demonstrated excellent antibacterial efficacy against both

Escherichia coli and

Staphylococcus aureus. Furthermore, the maximum tolerable silver-ion concentration for human cells has been reported to be around 10 ppm [

16,

17]. After 180 days of immersion in PBS, the cumulative Ag

+ release from the HiPIMS-Ag films reached only 518 ppb, which is nearly four orders of magnitude lower than the cytotoxic limit. Based on the steady-state release rate of 0.43 ppb/day observed in the third stage of ion release, extrapolation suggests that the total Ag

+ concentration would remain below the cytotoxic limit for more than 60 years, indicating excellent long-term cytocompatibility. Although Ag

+ can temporarily or chronically accumulate in human organs such as the kidneys, liver, and bones, they are gradually excreted through bile, urine, hair, and nails [

19]. Considering the body’s inherent capability for Ag

+ absorption and metabolic clearance, the actual cytotoxic risk from the HiPIMS-Ag coating during clinical use is expected to be even lower. Overall, this study demonstrates that the Ag

+ release behavior of the HiPIMS-Ag coatings falls within a “safe operating window,” defined as 0.1 ppb < [Ag

+] < 10

4 ppb (10 ppm). The lower bound ensures antibacterial effectiveness, while the upper bound maintains cytocompatibility, confirming that HiPIMS-Ag films occupy a stable and biologically safe “Goldilocks regime”, thereby decreasing the detrimental risk from over-release of silver ions. In addition, this study also found that the ion release kinetics of the HiPIMS-Ag coating can be divided into three distinct stages:

- (1)

Stage I—Rapid release phase: an initial burst providing immediate postoperative antibacterial protection.

- (2)

Stage II—Stable release phase: a controlled release maintaining antibacterial efficacy.

- (3)

Stage III—Slow release phase: a long-term sustained release ensuring durable protection without cytotoxicity.

This three-stage behavior effectively satisfies the functional requirements of antibacterial orthopedic implants—delivering both immediate and prolonged antibacterial activity while maintaining excellent biocompatibility.

Third, while silver is sometimes criticized for potential interference with osteogenesis at high concentrations, the trace-level Ag

+ release measured here—paired with the favorable MC3T3-E1 responses—indicates that HiPIMS-Ag can inhabit a safe operating window in vitro. On the other hand, it is well established that the initial adsorption of proteins (e.g., albumin, fibronectin, and vitronectin) on implant surfaces can critically influence subsequent cell adhesion and bacterial colonization [

20]. Given the dense, smooth, and crystalline morphology of the HiPIMS-Ag coatings, it is expected that the surface may selectively adsorb proteins with lower affinity for bacterial adhesion, thereby reducing bacterial anchoring and biofilm formation. At the same time, moderate protein adsorption could facilitate osteoblast attachment without compromising antibacterial performance. Moreover, the trace-level Ag

+ release (~0.43 ppb/day) observed in this study might further modulate the composition or conformation of the adsorbed protein layer, influencing the delicate balance between cytocompatibility and antibacterial activity. Collectively, these hypotheses suggest that the interactions among protein adsorption, conditioning-film formation, and the HiPIMS-Ag surface could play a critical role in determining long-term biological outcomes—representing a worthwhile direction for future investigation.

Finally, compared to nanoparticle-based approaches, thin-film Ag coatings—especially those prepared using HiPIMS process—can avoid particle detachment and limit burst-release behavior [

21]. As mentioned in the Introduction section, nanoparticle- or composite-based Ag coatings often suffer from mechanical instability due to weak interfacial bonding with the substrate and the discrete nature of embedded or loosely bound Ag particles. Under physiological or mechanical stresses, such particulate coatings can experience particle detachment, leading to uncontrolled or “burst” Ag

+ release and potential local cytotoxicity [

3,

5]. In contrast, the HiPIMS process produces a dense, continuous, and strongly adherent silver film through a highly ionized plasma with energetic ion bombardment. This ion-assisted growth mechanism promotes atomic-scale intermixing and densification at the film–substrate interface, resulting in exceptional adhesion (ASTM 5B and VDI HF1 ratings in this study). The continuous film structure eliminates particulate boundaries, thereby preventing detachment and ensuring that Ag

+ release occurs solely through surface-mediated reactions rather than physical particle loss. Consequently, the HiPIMS-Ag thin film achieves long-term stability and a controlled, steady-state Ag

+ release profile, demonstrating the advantages of high interfacial integrity and microstructural compactness that underpin its superior durability and biocompatibility for orthopedic applications. In addition, HiPIMS-Ag coating can also simplify sterilization and packaging workflows, as continuous metallic layers generally withstand common sterilization methods without significant degradation. The present focus was on antibacterial efficacy and cytocompatibility; nevertheless, the favorable adhesion and microstructure achieved by HiPIMS provide a solid platform for downstream evaluations, including sterilization resistance, long-term immersion studies, and device-specific validation [

4].