Polyvinyl Alcohol and Nano-Clay Based Solution Processed Packaging Coatings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Processing of Films

2.3. Characterization of Films

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siracusa, V. Food packaging permeability behaviour: A Report. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2012, 2012, 302029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figura, L.O.; Teixeira, A.A. Food Physics, Physical Proerties-Measurements and Applicartions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 39, pp. 561–563. [Google Scholar]

- Channa, I.A.; Distler, A.; Egelhaaf, H.; Brabec, C.J. Solution Coated Barriers for Flexible Electronics. In Organic Flexible Electronics, Fundamentals, Devices, and Applications; Cosseddu, P., Caironi, M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Channa, I.A.; Distler, A.; Zaiser, M.; Brabec, C.J.; Egelhaaf, H. Thin film encapsulation of organic solar cells by direct deposition of polysilazanes from solution. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1900598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooksey, K. Important Factors for Selecting; Packag: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Geueke, B.; Groh, K.; Muncke, J. Food packaging in the circular economy: Overview of chemical safety aspects for commonly used materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channa, I.A. Development of Solution Processed Thin Film Barriers for Encapsulating Thin Film Electronics; Friedrich Alexander University of Erlangen Nuremberg: Bavaria, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Raheem, D. Application of plastics and paper as food packaging materials? An overview. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2013, 25, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustace, I.J. Some factors affecting oxygen transmission rates of plastic films for vacuum packaging of meat. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, I.; Nayik, G.A.; Dar, S.M.; Nanda, V. Novel food packaging technologies: Innovations and future prospective. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018, 17, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, C.; Duraccio, D.; Cimmino, S. Food packaging based on polymer nanomaterials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 1766–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Lee, H.S. Water and oxygen permeation through transparent ethylene vinyl alcohol/(graphene oxide) membranes. Carbon Lett. 2014, 15, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarenko, S.; Meneghetti, P.; Julmon, P.; Olson, B.; Qutubuddin, S. Gas barrier of polystyrene montmorillonite clay nanocomposites: Effect of mineral layer aggregation. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2007, 45, 1733–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granstrom, J.; Roy, A.; Rowell, G.; Moon, J.S.; Jerkunica, E.; Heeger, A.J. Improvements in barrier performance of perfluorinated polymer films through suppression of instability during film formation. Thin Solid Films 2010, 518, 3767–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Bugnicourt, E.; Latorre, M.; Jorda, M.; Echegoyen Sanz, Y.; Lagaron, J.; Miesbauer, O.; Bianchin, A.; Hankin, S.; Bölz, U.; et al. Review on the processing and properties of polymer nanocomposites and nanocoatings and their applications in the packaging, automotive and solar energy fields. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokwena, K.K.; Tang, J. Ethylene vinyl alcohol: A review of barrier properties for packaging shelf stable foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammann, F.; Schmid, M. Determination and quantification of molecular interactions in protein films: A review. Materials 2014, 7, 7975–7996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, M.; Dallmann, K.; Bugnicourt, E.; Cordoni, D.; Wild, F.; Lazzeri, A.; Noller, K. Properties of whey-protein-coated films and laminates as novel recyclable food packaging materials with excellent barrier properties. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2012, 2012, 562381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Zillinger, W.; Müller, K.; Sängerlaub, S. Permeation of water vapour, nitrogen, oxygen and carbon dioxide through whey protein isolate based films and coatings—Permselectivity and activation energy. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2015, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, C.S.; Lopez, A.D.; Ramos, M.H.; Ballester, V.A.C. Nanomaterials: A map for their selection in food packaging applications. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2014, 27, 839–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Jini, D.; Aravind, M.; Parvathiraja, C.; Ali, R.; Kiyani, M.Z.; Alothman, A. A novel study on synthesis of egg shell based activated carbon for degradation of methylene blue via photocatalysis. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 8717–8722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, J.H.; Lee, C.H.; Park, C.-S.; Lee, K.-J.; Nam, J.-D.; Kim, S.W. Rheological, morphological, mechanical, and barrier properties of PP/EVOH blends. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2001, 20, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, V.; Ingrao, C.; Giudice, A.L.; Mbohwa, C.; Rosa, M.D. Environmental assessment of a multilayer polymer bag for food packaging and preservation: An LCA approach. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Iacovidou, E. Closing the loop on plastic packaging materials: What is quality and how does it affect their circularity? Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 1394–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaume, J.; Taviot-Gueho, C.; Cros, S.; Rivaton, A.; Thérias, S.; Gardette, J.L. Optimization of PVA clay nanocomposite for ultra-barrier multilayer encapsulation of organic solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2012, 99, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawhecker, K.E.; Manias, E. Nanocomposites based on water soluble polymers and unmodified smectide clays. Polym. Nanocompos. 2006, 206, 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, J.; Bazaka, K.; Anderson, L.J.; White, R.; Jacob, M. Materials and methods for encapsulation of OPV: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atai, M.; Solhi, L.; Nodehi, A.; Mirabedini, S.M.; Kasraei, S.; Akbari, K.; Babanzadeh, S. PMMA-grafted nanoclay as novel filler for dental adhesives. Dent. Mater. 2009, 25, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, A.K.; Achilias, D.S.; Karayannidis, G.P. Synthesis and characterization of PMMA/organomodified montmorillonite nanocomposites prepared by in situ bulk polymerization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seethamraju, S.; Ramamurthy, P.; Madras, G. Performance of an ionomer blend-nanocomposite as an effective gas barrier material for organic devices. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 11176–11187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hong, S.I.; Lee, H.; Rhim, J. Effects of clay type and content on mechanical, water barrier and antimicrobial properties of agar-based nanocomposite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 691–699. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, S. Photovoltaic Module Reliability Workshop 2012: February 28–March 1, 2012; Office of Scientific and Technical Information (OSTI): Zhenjiang, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carosio, F.; Colonna, S.; Fina, A.; Rydzek, G.; Hemmerlé, J.; Jierry, L.; Schaaf, P.; Boulmedais, F. Efficient gas and water vapor barrier properties of thin poly(lactic acid) packaging films: Functionalization with moisture resistant nafion and clay multilayers. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 5459–5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.-Y.; Lin, M.-J.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Chou, P.-C. Effects of modified clay on the morphology and thermal stability of PMMA/clay nanocomposites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbaghianamiri, M.; Duraia, E.-S.M.; Beall, G.W. Self-assembled Montmorillonite clay-poly vinyl alcohol nanocomposite as a safe and efficient gas barrier. Results Mater. 2020, 7, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurko, E.S.; Feicht, P.; Habel, C.; Schilling, T.; Daab, M.; Rosenfeldt, S.; Breu, J. Can high oxygen and water vapor barrier nanocomposite coatings be obtained with a waterborne formulation? J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 540, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, Z.W.; Dong, Y.; Han, N.; Liu, S. Water and gas barrier properties of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)/starch (ST)/ glycerol (GL)/halloysite nanotube (HNT) bionanocomposite films: Experimental characterisation and modelling approach. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 174, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangreez, T.A.; Mobin, R. 13-Polymer composites for dental fillings. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomaterials [Internet]; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2019; pp. 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhu, P.; Zhou, M.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, F. Effect of Microfibrillated cellulose loading on physical properties of starch/polyvinyl Al-cohol composite films. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2020, 35, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Tang, K.; Liu, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y. Compatibility and properties of biodegradable blend films with gelatin and poly(vinyl al-cohol). J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Sci. Ed. 2014, 29, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, M.C.; Erdmann, E.; Destéfanis, H.A. Preparation of Poli (Vinylalcohol)/Organoclay Nanocomposites by Casting and in Situ Polymerization. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Composite Materials, Venice, Italy, 24–28 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, Y.; Peruzzo, P.J.; Fernández, M.; Paulis, M.; Leiza, J.R. Encapsulation of clay within polymer particles in a high-solids content aqueous dispersion. Langmuir 2013, 29, 9849–9856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Fisher, A.; Foo, P.; Queen, D.; Gaylor, J. In vitro assessment of water vapour transmission of synthetic wound dressings. Biomaterials 1995, 16, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manias, E.; Touny, A.; Wu, L.; Strawhecker, K.; Lu, B.; Chung, T.C. Polypropylene/montmorillonite nanocomposites. Review of the synthetic routes and materials properties. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 3516–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, R.K. Modeling the barrier properties of polymer-layered silicate nanocomposites. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 9189–9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channa, I.A.; Distler, A.; Scharfe, B.; Feroze, S.; Forberich, K.; Lipovšek, B.; Brabec, C.J.; Egelhaaf, H.-J. Solution processed oxygen and moisture barrier based on glass flakes for encapsulation of organic (opto-) electronic devices. Flex. Print. Electron. 2021, 6, 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channa, I.; Chandio, A.; Rizwan, M.; Shah, A.; Bhatti, J.; Shah, A.; Hussain, F.; Shar, M.; AlHazaa, A. Solution processed PVB/mica flake coatings for the encapsulation of organic solar cells. Materials 2021, 14, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

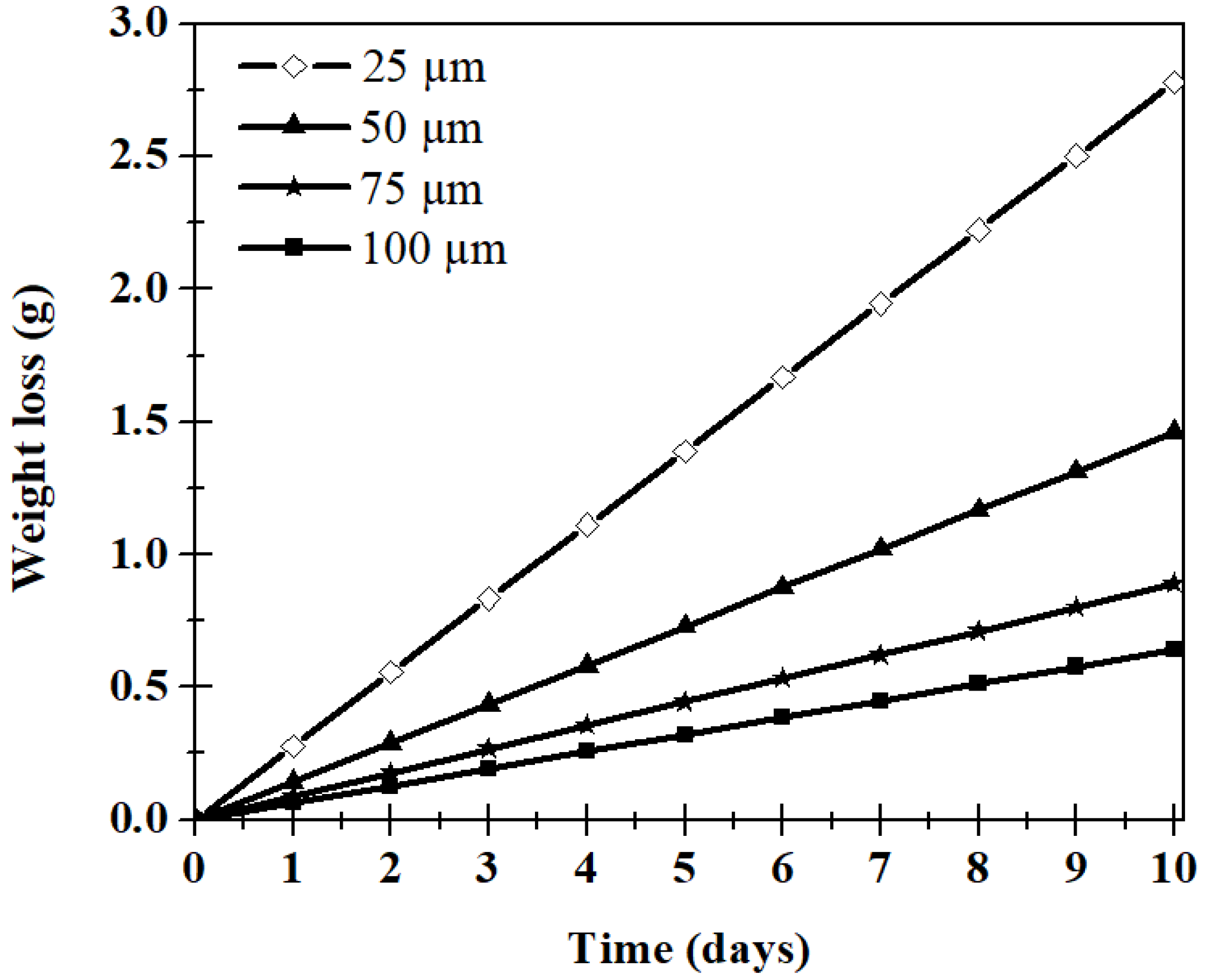

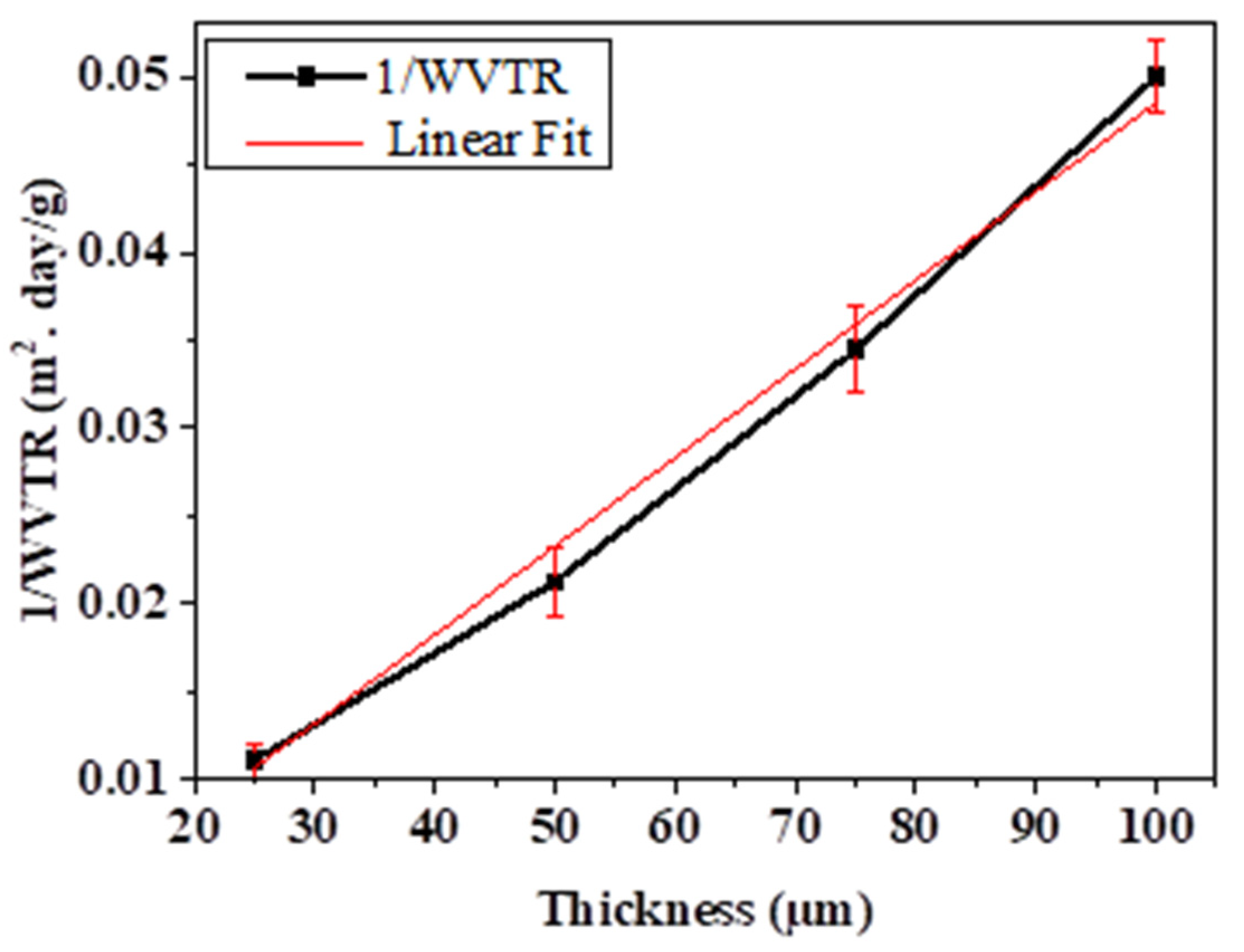

| Film Thickness (µm) | WVTR (g/(m2·Day)) |

|---|---|

| 25 | 90 ± 5.2 |

| 50 | 47 ± 4.2 |

| 75 | 29 ± 3.4 |

| 100 | 20.5 ± 2.5 |

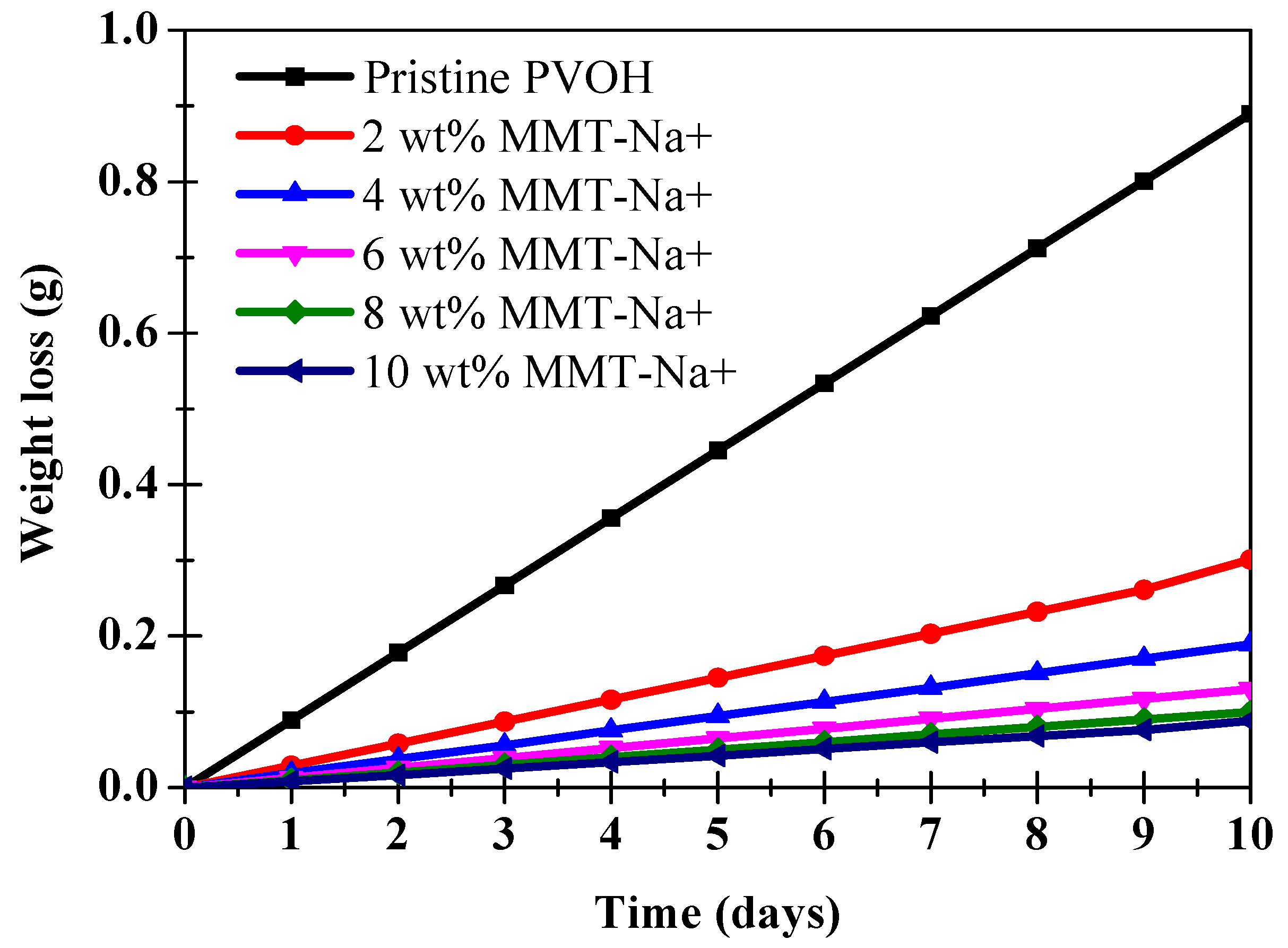

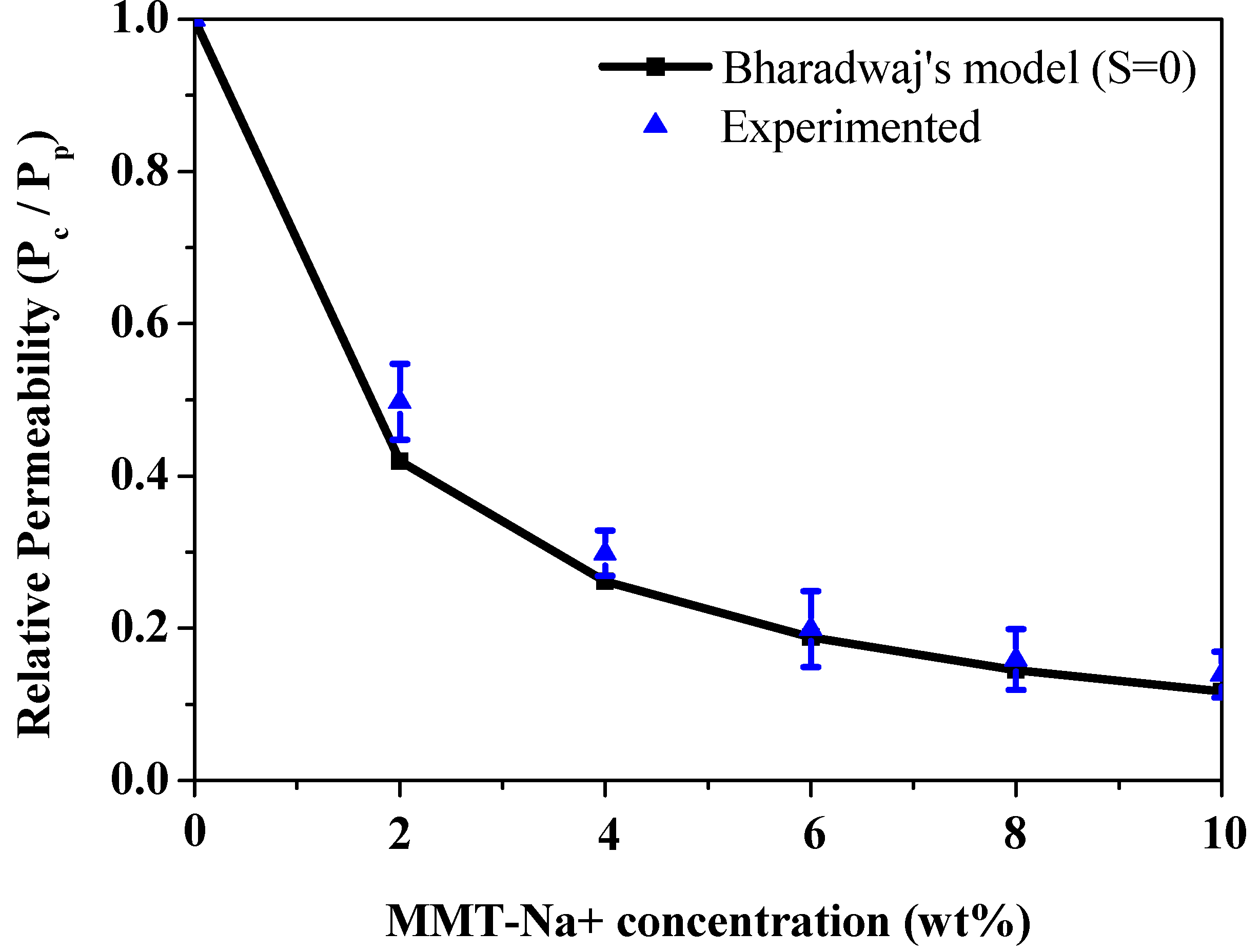

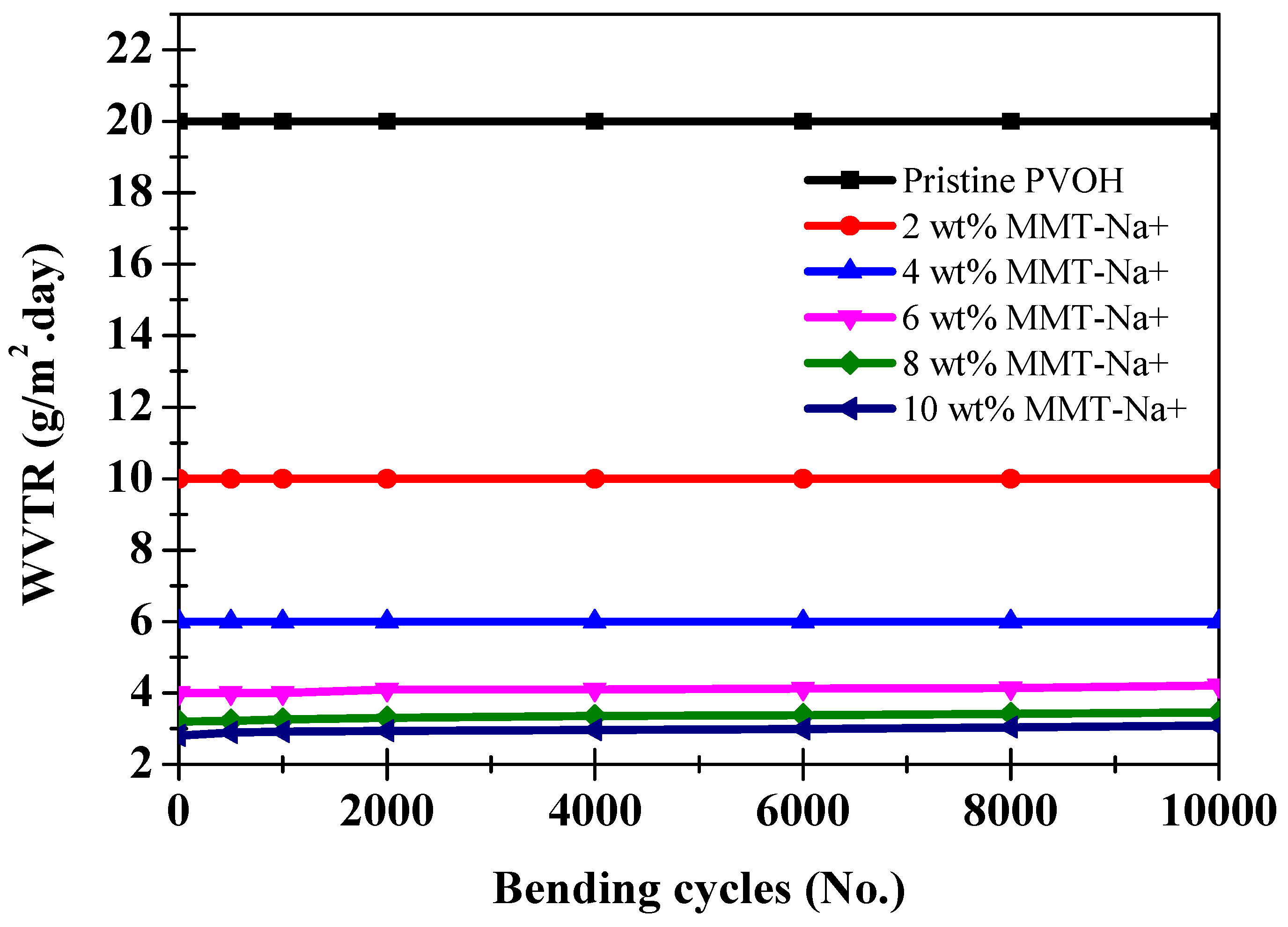

| Films | WVTR (g/m2·Day) | Permeability (g·cm/(m2·Day)) |

|---|---|---|

| Pristine PVOH | 20.5 ± 2.5 | 2.05 × 10−1 |

| PVOH/MMT-Na+ (2 wt.%) | 10 ± 1.3 | 1.1 × 10−1 |

| PVOH/MMT-Na+ (4 wt.%) | 6 ± 0.5 | 6 × 10−2 |

| PVOH/MMT-Na+ (6 wt.%) | 4 ± 0.3 | 4 × 10−2 |

| PVOH/MMT-Na+ (8 wt.%) | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 3.2 × 10−2 |

| PVOH/MMT-Na+ (10 wt.%) | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.8 × 10−2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chandio, A.D.; Channa, I.A.; Rizwan, M.; Akram, S.; Javed, M.S.; Siyal, S.H.; Saleem, M.; Makhdoom, M.A.; Ashfaq, T.; Khan, S.; et al. Polyvinyl Alcohol and Nano-Clay Based Solution Processed Packaging Coatings. Coatings 2021, 11, 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11080942

Chandio AD, Channa IA, Rizwan M, Akram S, Javed MS, Siyal SH, Saleem M, Makhdoom MA, Ashfaq T, Khan S, et al. Polyvinyl Alcohol and Nano-Clay Based Solution Processed Packaging Coatings. Coatings. 2021; 11(8):942. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11080942

Chicago/Turabian StyleChandio, Ali Dad, Iftikhar Ahmed Channa, Muhammad Rizwan, Shakeel Akram, Muhammad Sufyan Javed, Sajid Hussain Siyal, Muhammad Saleem, Muhammad Atif Makhdoom, Tayyaba Ashfaq, Safia Khan, and et al. 2021. "Polyvinyl Alcohol and Nano-Clay Based Solution Processed Packaging Coatings" Coatings 11, no. 8: 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11080942

APA StyleChandio, A. D., Channa, I. A., Rizwan, M., Akram, S., Javed, M. S., Siyal, S. H., Saleem, M., Makhdoom, M. A., Ashfaq, T., Khan, S., Hussain, S., Albaqami, M. D., & Alotabi, R. G. (2021). Polyvinyl Alcohol and Nano-Clay Based Solution Processed Packaging Coatings. Coatings, 11(8), 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11080942