Antimicrobial Activity of Nitrogen-Containing 5-α-Androstane Derivatives: In Silico and Experimental Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

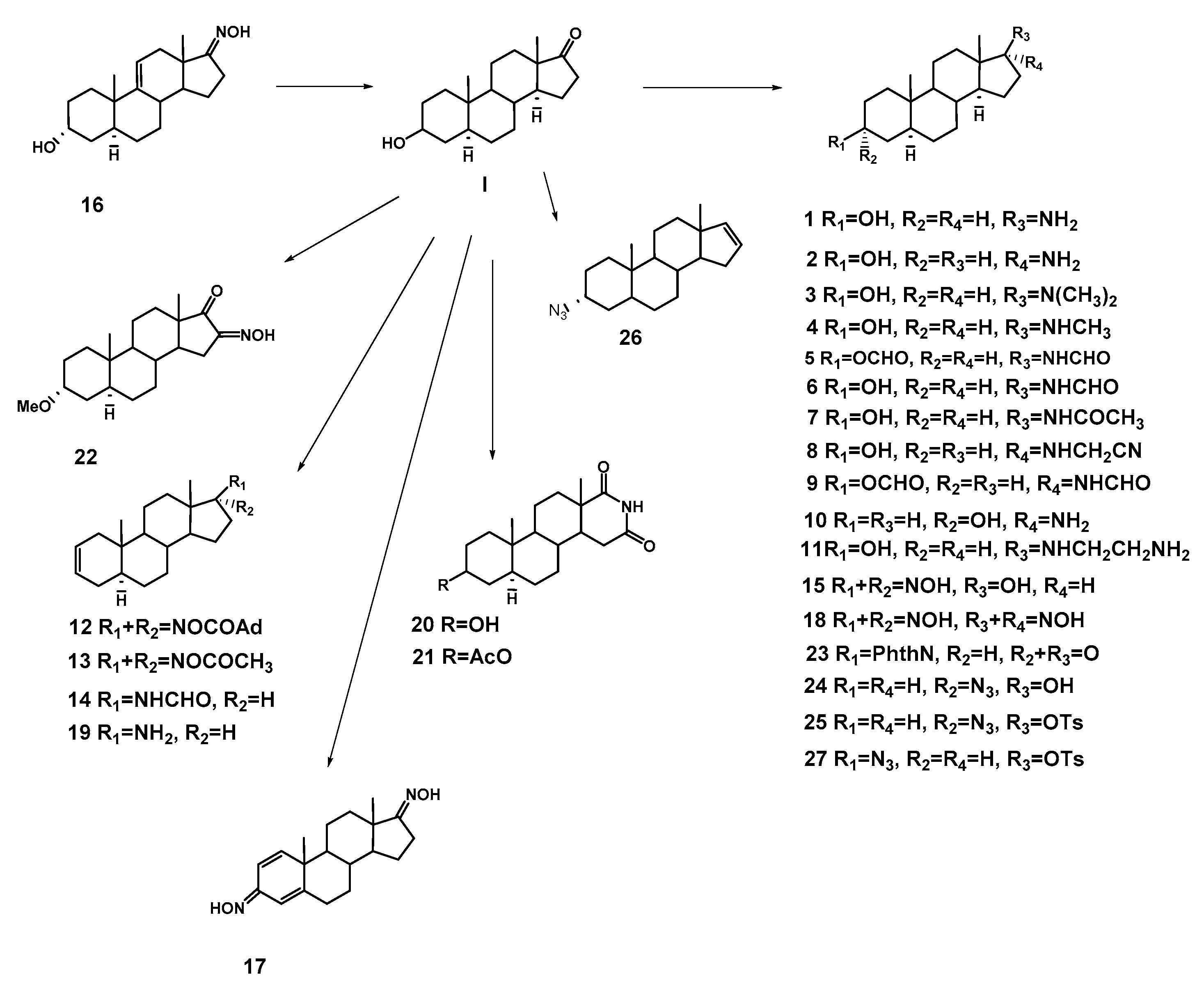

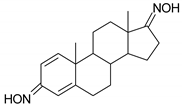

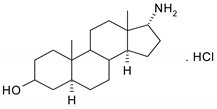

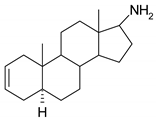

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Biological Activity and Toxicity Predictions

2.3. Biological Evaluation

2.3.1. Antimicrobial Activity

2.3.2. Evaluation of Antifungal Activity

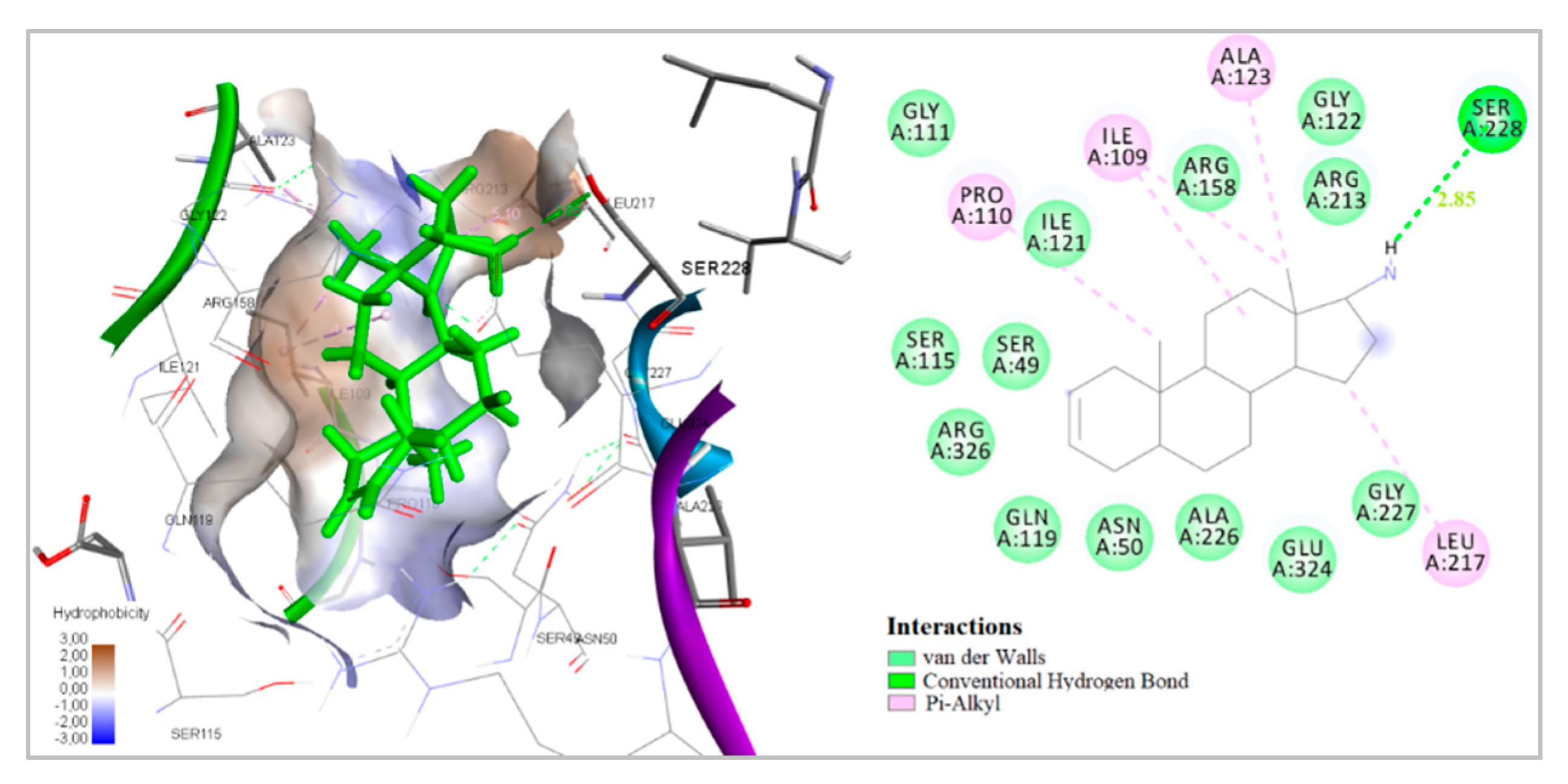

2.4. Docking to Antibacterial Targets

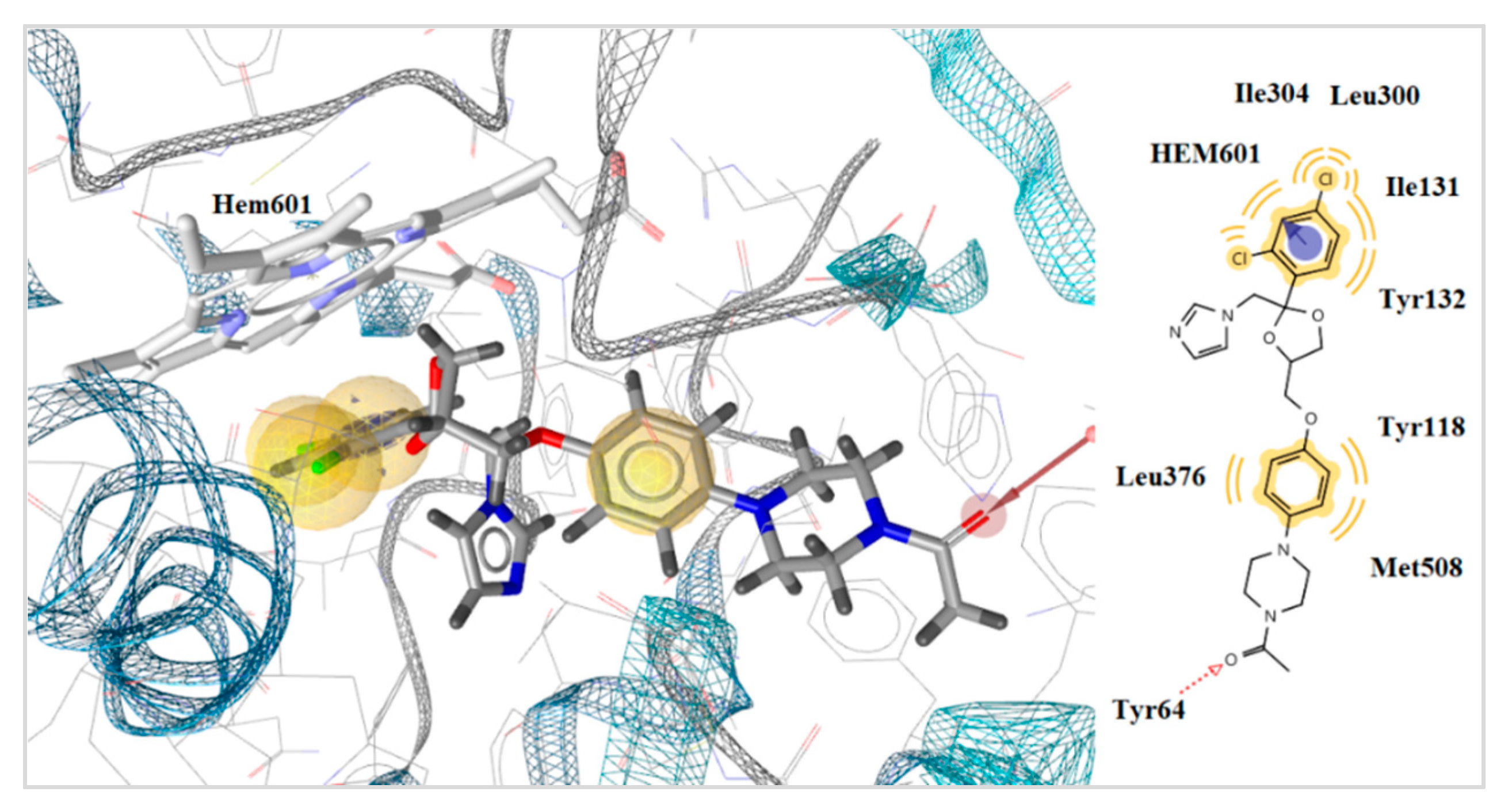

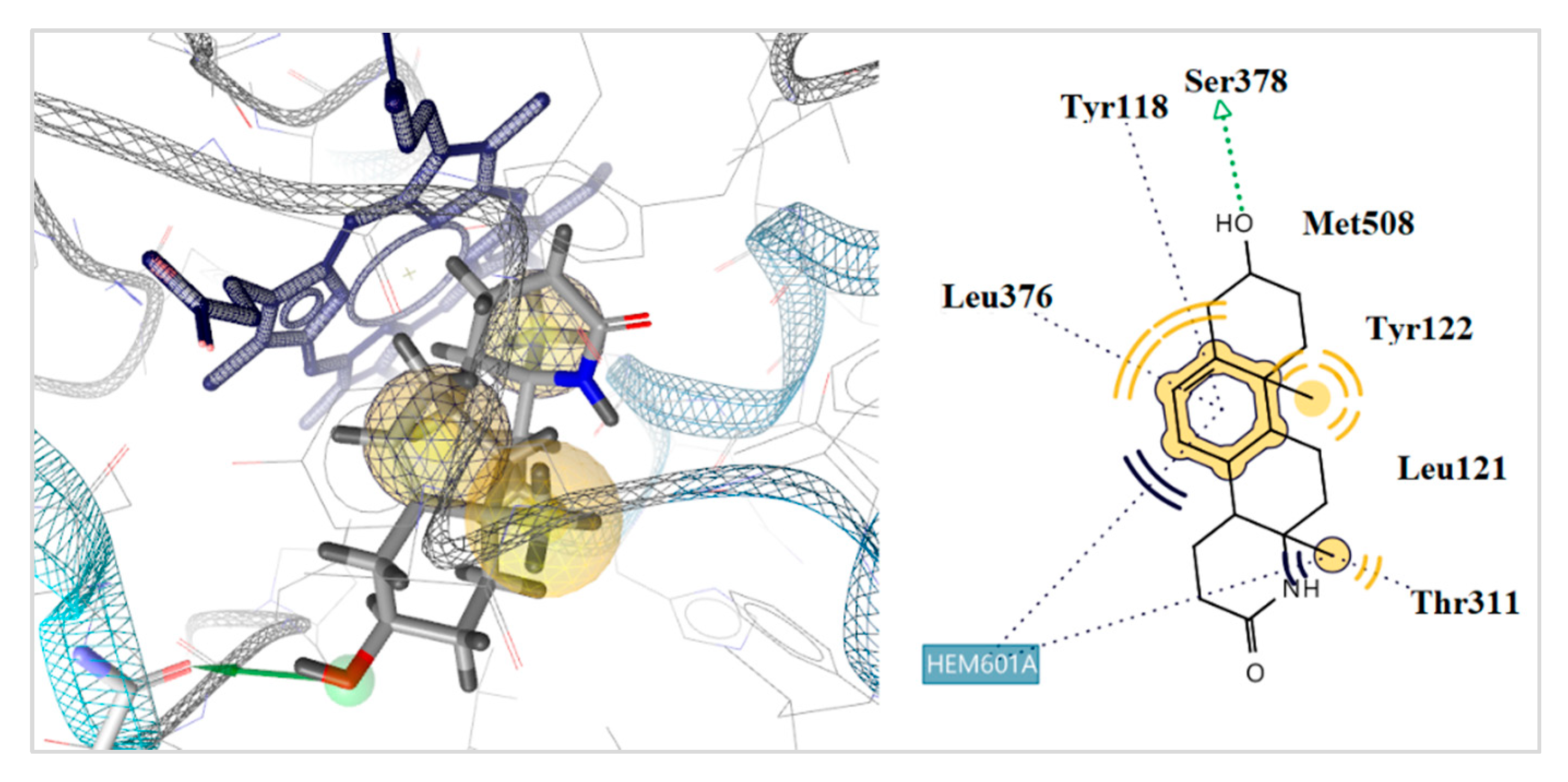

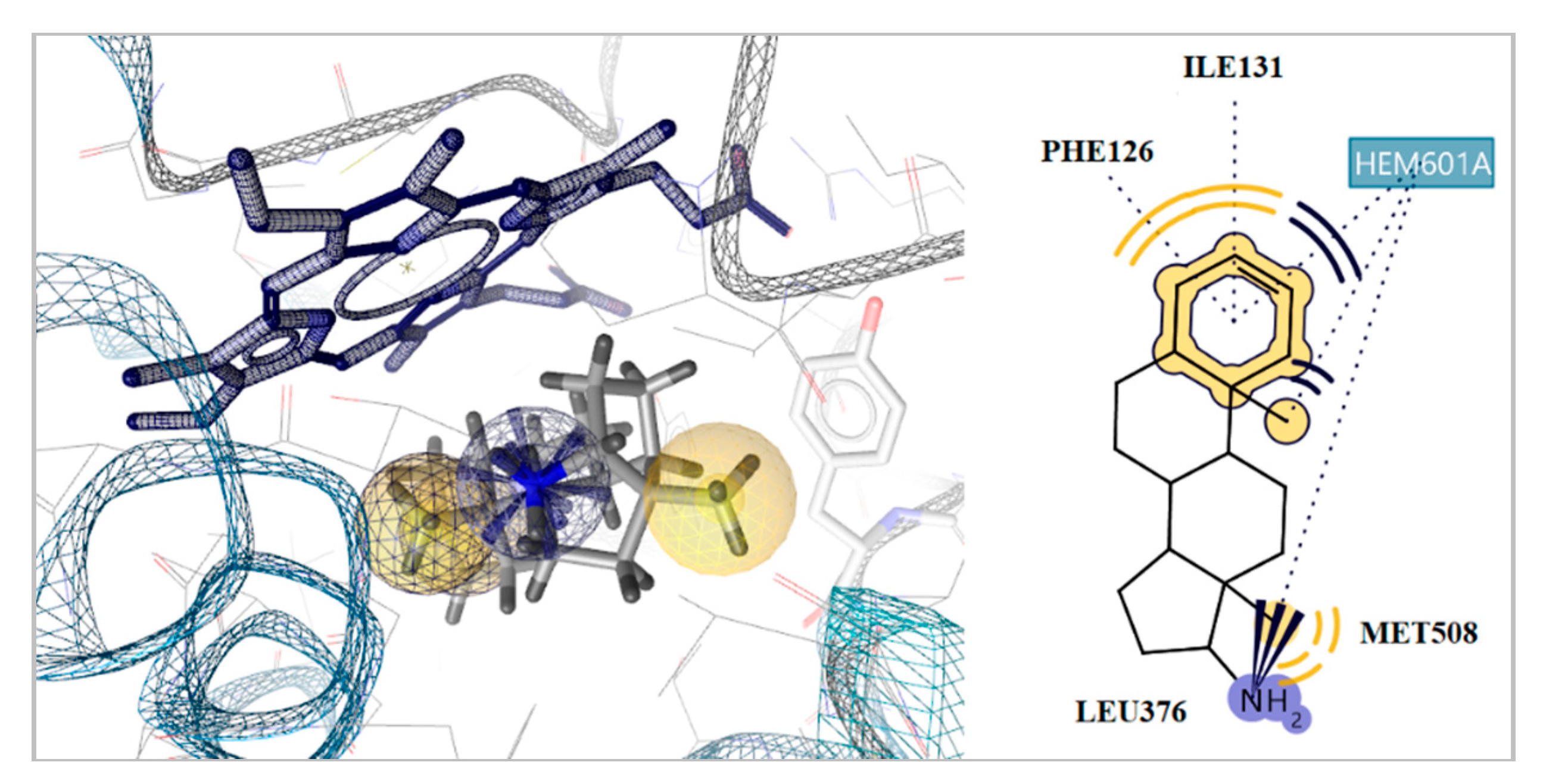

2.5. Docking to Antifungal Targets

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activity Prediction

3.2. Biological Evaluation

3.2.1. Antibacterial Activity

Microdilution Test

3.2.2. Antifungal Activity

3.3. Docking Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/index.html (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Cornaglia, G. Fighting infections due to multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens. Clin. Microb. Infect. 2009, 15, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calfee, D.P. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and other Gram-positives in healthcare. Curr. Opin. 2012, 25, 285–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Choe, P.G.; Song, K.H.; Park, S.W.; Kim, H.B.; Kim, N.J.; Kim, E.C.; Park, W.B.; Oh, M.D. Is cefazolin inferior to nafcillin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 5122–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, H.B.; Kim, N.J.; Kim, E.C.; Oh, M.D.; Choe, K.W. Outcome of vancomycin treatment in patients with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holmes, N.E.; Howden, B.P. What’s new in the treatment of serious MRSA infection? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 27, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, E.J.; Chambers, H.F. Treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J. Infect. Chemother. 2016, 48, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Picconi, P.; Hind, C.; Jamshidi, S.; Nahar, K.; Clifford, M.; Wand, M.E.; Sutton, J.M.; Rahman, K.M. Triaryl Benzimidazoles as a new class of antibacterial agents against resistant pathogenic microorganisms. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 6045–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.; Czaplewski, L.; Piddock, L.J.V. Discovery and development of new antibacterial drugs: Learning from experience? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giannakaki, V.; Miyakis, S. Novel antimicrobial agents against multi-drug-resistant gram-positive bacteria: An overview. Recent Pat. Antiinfect. Drug Discov. 2012, 7, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.S.; Menagen, B.; Avnir, D.; Hayouka, Z. Random peptide mixtures entrapped within a copper-cuprite matrix: New antimicrobial agent against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Βorde, R.Μ.; Jadhav, S.B.; Dhavse, R.R.; Munde, A.C. Design, synthesis, and pharmacological evaluation of some novel bis-thiazole derivatives. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezki, N.; Al-Yahyawi, A.M.; Bardaweel, S.K.; Al-Blewi, F.F.; Aouad, M.R. Synthesis of Novel 2,5-Disubstituted-1,3,4-thiadiazoles Clubbed 1,2,4-Triazole, 1,3,4-Thiadiazole, 1,3,4-Oxadiazole and/or Schiff Base as Potential Antimicrobial and Antiproliferative Agents. Molecules 2015, 20, 16048–16067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lone, I.H.; Khan, K.Z.; Fozdar, B.I.; Hussain, F. Synthesis antimicrobial and antioxidant studies of new oximes of steroidal chalcones. Steroids 2013, 78, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.; Lee, D.U. Green synthesis, biochemical and quantum chemical studies of steroidal oximes. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 32, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Choi, B.S.; Kwon, K.C.; Lee, S.O.; Kwak, H.J.; Lee, C.H. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of squalamine analogue. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000, 8, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, H.S. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of 7-fluoro-3-aminosteroids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 5139–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Jung, Y.M.; Kim, B.J.; Cho, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.-S. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of 7α-amino-23,24-bisnor-5α-cholan-22-ol derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 2558–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, C.; Loncle, C.; Letourneux, Y.; Brunel, J.M. Efficient preparation of secondary aminoalcohols through a Ti(IV) reductive amination procedure. Application to the synthesis and antibacterial evaluation of new 3β-N-[hydroxyalkyl]aminosteroid derivatives. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 4453–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, C.; Loncle, C.; Vidal, N.; Laget, M.; Letourneux, Y.; Michel Brunel, J. Antimicrobial Activities of 3-Amino- and Polyaminosterol Analogues of Squalamine and Trodusquemine. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2008, 23, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadaraia, N.S.; Amiranashvili, L.S.; Merlani, M.I. Structure-Activity Relationship of Epimeric 3,17-Substituted 5α-Androstane Aminoalcohols. Chem. Nat. Compds. 2016, 52, 961–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadaraia, N.S.; Amiranashvili, L.S.; Merlani, M.; Kakhabrishvili, M.L.; Barbakadze, N.N.; Geronikaki, A.; Petrou, A.; Poroikov, V.; Ciric, A.; Glamoclija, J.; et al. Novel antimicrobial agents discovery among the steroid derivatives. Steroids 2019, 144, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimstra, P.D. 3α-azido-5α-androstan-17-one and derivatives thereof. US3350424A, 31 October 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Genin, M.J.; Allwine, D.A.; Anderson, D.J.; Barbachyn, M.R.; Emmert, D.E.; Garmon, S.A.; Graber, D.R.; Grega, K.C.; Hester, J.B.; Hutchinson, D.K. Substituent effects on the antibacterial activity of nitrogen-carbon-linked (azolylphenyl)oxazolidinones with expanded activity against the fastidious Gram-negative organisms Haemophilus Influenza and Moraxella catarrhalis. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 43, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kádár, Z.; Kovács, D.; Frank, E.; Schneider, G.; Huber, J.; Zupkó, I.; Bartók, T.; Wölfling, J. Synthesis and In Vitro Antiproliferative Activity of Novel Androst-5-ene Triazolyl and Tetrazolyl Derivatives. Molecules 2011, 16, 4786–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, J.M.; Cocolas, C.H.; Hall, I.H. Hypolipidemic Activity of Phthalimide Derivatives IV: Further Chemical Modification and Investigation of the Hypolipidemic Activity of N-substituted imides. J. Pharm. Sci. 1983, 72, 1344–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinji, C.; Nakamura, T.; Maeda, S.; Yoshida, M.; Hashimotoa, Y.; Miyachia, H. Design and synthesis of phthalimide-type histone deacetylase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 4427–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyar, A.; Jain, R. Recent Advances in New Structural Classes of Anti-Tuberculosis Agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 1873–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camoutsis, C.; Trafalis, D.T.P. An overview on the antileukemic potential of d-homo-aza- and respective 17beta-acetamido-steroidal alkylating esters. Invest. New Drugs 2003, 21, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruya, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Koyama, T.; Suenaga, K.; Kita, M.; Uemura, D. Nakiterpiosin, a novel cytotoxic C-nor-D-homosteroid from the Okinawan sponge Terpios hoshinota. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 5171–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, G.L.; Kinsman, O.S. Synthesis and antifungal activity of novel aza-d-homosteroids, hydroisoquinolines, pyridines and dihydropyridines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 3, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlani, M.I.; Amiranashvili, L.S.; Mulkidzhanyan, K.G.; Kemertelidze, E.P. Synthesis and biological activity of certain amino-derivatives of 5α-steroids. Chem. Nat. Compds. 2006, 42, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadaraia, N.S.; Sladkov, V.I.; Dorodnikova, E.V.; Mashkovskii, M.D.; Kemertelidze, E.P.; Suvorov, N.N. Synthesis and antiarrhythmic activity of epimeric 17-amino-5α-androstan-3-ols and their derivatives. Russ. Khim.-Farm. Zh. 1988, 22, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemertelidze, E.P.; Benidze, M.M.; Skhirtladze, A.B.; Nadaraia, N.S.; Merlani, M.I.; Amiranashvili, L.S. Synthesis of Steroidal Hormonal Preparations on the Basis of Tigogenin from Yucca gloriosa L, Introduced in Georgia and Studying of the Chemical Composition of the Plant; Georgian National Academy Press: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2018; pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Merlani, M.I.; Davitishvili, M.G.; Nadaraia, N.S.; Sikharulidze, M.I.; Papadopulos, K. Conversion of epiandrosterone into 17β-amino-5α-androstane. Chem. Nat. Compds. 2004, 40, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlani, M.I.; Amiranashvili, L.S.; Mulkidzhanyan, K.G.; Shelar, A.R.; Manvi, F.V. Synthesis and antituberculosis activity of certain steroidal derivatives of the 5α-series. Chem. Nat. Compds. 2008, 44, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikharulidze, M.I.; Nadaraia, N.S.; Kakhabrishvili, M.L.; Barbakadze, N.N. Synthesis and biological activity some derivatives of 5α-androst-2-en-17-one. Coll. Sci. Wrk. Tbilisi State Med. Univ. 2012, XLVI, 148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sikharulidze, M.I.; Nadaraia, N.S.; Kakhabrishvili, M.L.; Barbakadze, N.N.; Mulkidzhanyan, K.G. Synthesis and biological activity of several steroidal oximes. Chem. Nat. Compds. 2010, 46, 493–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camoutsis, C.; Catsoulacos, P. Formation of Bishomoazasteroids by the Beckmann Rearrangement. J. Heterocyc. Chem. 1988, 25, 1617–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlani, M.I.; Amiranashvili, L.S.; Mulkidzhanyan, K.G.; Shelar, A.R. Synthesis and antitumor activity of some 5α-steroid derivatives. Chem. Nat. Compds. 2008, 44, 819–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiranashvili, L.S.; Sladkov, V.I.; Lindeman, S.V.; Aleksanian, M.S.; Struchkov, Y.T.; Suvorov, N.N. Synthesis 16β-amino-3 β,17β-dihydroxy-5α-androstane on the basis epiandrosterone and structure its triacetate derivative. Zhurnal organicheskoĭ khimii 1990, 29, 1052–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Merlani, M.I.; Amiranashvili, L.S.; Kemertelidze, E.P. Synthesis of several 5α-d-homosteroid derivatives based on tigogenine. Chem. Nat. Compds. 2014, 50, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiranashvili., L.S.; Sladkov, V.I.; Levina, I.I.; Mens’hova, N.I.; Suvorov, N.N. Synthesis of 3α-amino-5α-androstane-17α-ole. Zhurnal organicheskoĭ khimii 1990, 26, 1884–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Kapoor, V.K.; Bhardwaj, T.R.; Kaur, M. A facile route for the synthesis of bisquartenary azasteroids. Inter. J. Pharm & Pharm. Sci 2013, 5, 728–732. [Google Scholar]

- Catsoulacos, P.; Boutis, L. Aza –steroids. Beckmann rearrangement of 3-β-acetoxy-5-α-androstan-17-one oxime acetate with boron fluoride. Alkylating agents. Chimie Therapeutique 1973, 2, 315–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, S. Steroids XVI. Beckmann rearrangement of 17-ketosteroid oximes. J. Am.Chem.Soc. 1951, 73, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Druzhilovskiy, D.S.; Lagunin, A.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Dmitriev, A.V.; Pogodin, P.V.; Poroikov, V.V. Komp’yuternoe prognozirovanie spektrov biologicheskoi aktivnosti khimicheskikh soedinenii: Vozmozhnosti i ogranicheniya [Computer-aided prediction of biological activity spectra for chemical compounds: Opportunities and limitations]. Biomed. Chem. Res. Meth. 2018, 1, e00004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Lagunin, A.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Druzhilovskiy, D.S.; Pogodin, P.V.; Poroikov, V.V. Prediction of the biological activity spectra of organic compounds using the PASS online web resource. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2014, 50, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogodin, P.V.; Lagunin, A.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Druzhilovskiy, D.S.; Filimonov, D.A.; Poroikov, V.V. AntiBac-Pred: A Web Application for Predicting Antibacterial Activity of Chemical Compounds. J. Chem. Inform. Model. 2019, 59, 4513–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AntiBAC Pred web-service. Available online: http://www.way2drug.com/antibac/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- AntiFUN Pred web-service. Available online: http://www.way2drug.com/micF/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Filimonov, D.A.; Zakharov, A.V.; Lagunin, A.A.; Poroikov, V.V. QNA-based ‘Star Track’ QSAR approach. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2009, 20, 679–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.; Zakharov, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. QSAR modelling of rat acute toxicity on the basis of PASS prediction. Mol. Inform. 2011, 30, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rat Acute Toxicity Prediction. Available online: http://www.way2drug.com/gusar/acutoxpredict.html (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- OECD Chemical Hazard Classification. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/env/ehs/riskmanagement/classificationandlabellingofchemicals.htm] (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Lagunin, A.A.; Dubovskaja, V.I.; Rudik, A.V.; Pogodin, P.V.; Druzhilovskiy, D.S.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Filimonov, D.A.; Sastry, G.N.; Poroikov, V.V. CLC-Pred: A freely available web-service for in silico prediction of human cell line cytotoxicity for drug-like compounds. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CLC-Pred web-service. Available online: http://www.way2drug.com/Cell-line/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Tsukatani, T.; Suenaga, H.; Shiga, M.; Noguchi, K.; Ishiyama, M.; Ezoe, T.; Matsumoto, K.J. Comparison of the WST-8 colorimetric method and the CLSI broth microdilution method for susceptibility testing against drug-resistant bacteria. Microbiol. Method. 2012, 90, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically, Approved standard, 8th ed.; CLSI publication M07-A8; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fesatidou, M.; Zagaliotis, P.; Camoutsis, C.; Petrou, A.; Eleftheriou, P.; Tratrat, C.; Haroun, M.; Geronikaki, A.; Ciric, A.; Sokovic, M. 5-Adamantan thiadiazole- based thiazolidinones as antimicrobial agents. Design, synthesis, molecular docking and evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 4664–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

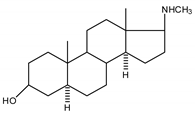

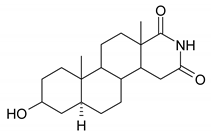

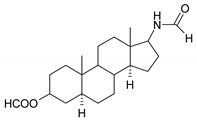

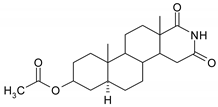

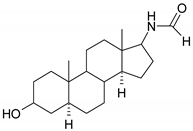

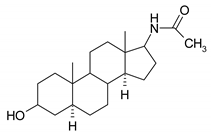

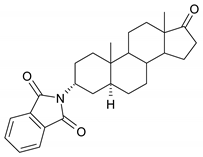

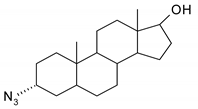

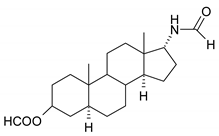

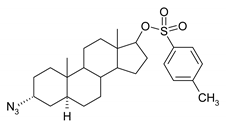

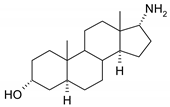

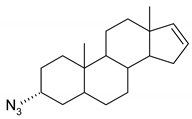

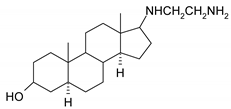

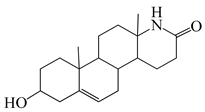

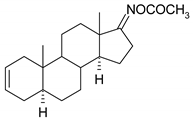

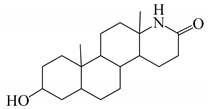

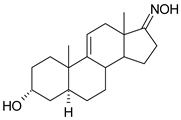

| N | Structure | N | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

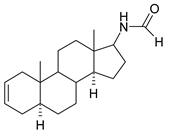

| 1 |  | 17 |  |

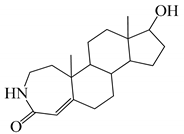

| 2 |  | 18 |  |

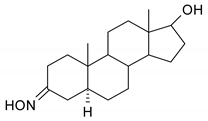

| 3 |  | 19 |  |

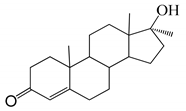

| 4 |  | 20 |  |

| 5 |  | 21 |  |

| 6 |  | 22 |  |

| 7 |  | 23 |  |

| 8 |  | 24 |  |

| 9 |  | 25 |  |

| 10 |  | 26 |  |

| 11 |  | 27 |  |

| 12 |  | 28 |  |

| 13 |  | 29 |  |

| 14 |  | 30 |  |

| 15 |  | 31 |  |

| 16 |  |

| N | Antibacterial Pa | Antifungal Pa | N | Antibacterial Pa | Antifungal Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.420 | 0.350 | 16 | 0.276 | 0.375 |

| 2 | 0.420 | 0.350 | 17 | 0.351 | - |

| 3 | 0.370 | 0.349 | 18 | 0.227 | 0.256 |

| 4 | 0.340 | 0.342 | 19 | 0.208 | 0.253 |

| 5 | 0.374 | 0.180 | 20 | 0.320 | 0.248 |

| 6 | 0.437 | 0.308 | 21 | 0.288 | 0.243 |

| 7 | 0.334 | 0.231 | 22 | 0.299 | 0.336 |

| 8 | 0.315 | 0.188 | 23 | 0.348 | - |

| 9 | 0.374 | 0.180 | 24 | 0.285 | 0.286 |

| 10 | 0.420 | 0.350 | 25 | 0.278 | 0.171 |

| 11 | 0.438 | 0.368 | 26 | 0.340 | 0.185 |

| 12 | 0.239 | 0.203 | 27 | 0.278 | 0.171 |

| 13 | 0.199 | 0.214 | 28 | - | - |

| 14 | 0.458 | 0.216 | 29 | - | - |

| 15 | 0.376 | 0.427 | 30 | - | - |

| 31 | - | - |

| Compounds | S. a. | MRSA | L. m. | P. a. | PaO1 | E. coli | E. coli res | S. thy. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MIC | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.025 | 0.037 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.025 |

| MBC | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.037 | |

| 2 | MIC | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.050 | 0.025 | 0.015 | 0.075 | 0.050 | 0.050 |

| MBC | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.075 | |

| 3 | MIC | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.30 | 0.15 | - | 0.020 | 0.020 |

| MBC | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.45 | 0.30 | - | 0.037 | 0.037 | |

| 4 | MIC | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.050 | 0.015 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.020 | 0.020 |

| MBC | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.037 | 0.037 | |

| 5 | MIC | 0.20 | 0.050 | 0.10 | 0.050 | - | - | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| MBC | 0.30 | 0.037 | 0.15 | 0.075 | - | - | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| 6 | MIC | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.30 | - |

| MBC | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.60 | - | |

| 7 | MIC | - | 0.075 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| MBC | - | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| 8 | MIC | 0.30 | 0.037 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| MBC | 0.45 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| 9 | MIC | - | 0.050 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.30 |

| MBC | - | 0.075 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.45 | |

| 10 | MIC | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.037 | 0.10 | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.020 |

| MBC | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.037 | |

| 11 | MIC | 0.050 | 0.005 | 0.10 | 0.020 | 0.10 | 0.050 | 0.037 | 0.10 |

| MBC | 0.075 | 0.007 | 0.15 | 0.037 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.15 | |

| 12 | MIC | - | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.15 | - |

| MBC | - | 0.15 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.30 | - | |

| 13 | MIC | - | 0.037 | - | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | - |

| MBC | - | 0.075 | - | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.30 | - | |

| 14 | MIC | 0.20 | 0.020 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| MBC | 0.30 | 0.037 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| 15 | MIC | - | 0.020 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.060 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| MBC | - | 0.040 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.080 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| 16 | MIC | 0.20 | 0.030 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| MBC | 0.30 | 0.040 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.30 | |

| 17 | MIC | - | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.15 | - | 0.15 | - | 0.30 |

| MBC | - | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.30 | - | 0.30 | - | 0.60 | |

| 18 | MIC | 0.30 | 0.075 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.20 | - | 0.30 |

| MBC | 0.60 | 0.15 | 0.60 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.30 | - | 0.60 | |

| 19 | MIC | 0.0005 | 0.00015 | 0.0015 | 0.0015 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| MBC | 0.0007 | 0.0003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.007 | |

| 20 | MIC | 0.20 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.020 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| MBC | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.037 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| 21 | MIC | - | 0.075 | 0.30 | - | - | - | 0.10 | 0.30 |

| MBC | - | 0.15 | 0.45 | - | - | - | 0.15 | 0.60 | |

| 22 | MIC | 0.10 | 0.0037 | 0.10 | 0.075 | 0.050 | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.15 |

| MBC | 0.15 | 0.015 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.30 | |

| 23 | MIC | 0.20 | 0.037 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| MBC | 0.30 | 0.075 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.075 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| 24 | MIC | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.075 | 0.050 | 0.05 | 0.007 | 0.20 |

| MBC | 0.45 | 0.075 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.30 | |

| 25 | MIC | - | 0.15 | - | - | - | - | 0.10 | - |

| MBC | - | 0.30 | - | - | - | - | 0.15 | - | |

| 26 | MIC | - | 0.037 | - | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.075 | - |

| MBC | - | 0.075 | - | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.15 | - | |

| 27 | MIC | - | 0.30 | - | - | - | 0.30 | - | - |

| MBC | - | 0.60 | - | - | - | 0.60 | - | - | |

| 28 | MIC | 0.15 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.02 | 0.007 | 0.02 | 0.037 | 0.15 |

| MBC | 0.30 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.30 | |

| 29 | MIC | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.075 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.15 |

| MBC | 0.60 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.45 | 0.30 | |

| 30 | MIC | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.10 |

| MBC | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| 31 | MIC | 0.45 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.45 |

| MBC | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.60 | |

| Streptomycin | MIC | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| MBC | 0.20 | - | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.1 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | |

| Ampicillin | MIC | 0.10 | - | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| MBC | 0.15 | - | 0.30 | 0.50 | - | 0.20 | - | 0.20 | |

| Compounds | A. fum. | A. v. | A. o. | A. n. | T. v. | P. f. | P. o. | P. v.c. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.007 | 0.037 | 0.007 | 0.037 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.010 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.075 | |

| 2 | MIC | 0.10 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.007 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.075 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.015 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.15 | |

| 3 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.015 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.037 | |

| 4 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.003 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.15 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.007 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.30 | |

| 5 | MIC | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.15 | 0.007 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.15 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.30 | 0.015 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.30 | |

| 6 | MIC | 0.45 | 0.075 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| MFC | 0.60 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 0.60 | |

| 7 | MIC | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.020 | 0.015 | 0.10 | 0.075 | 0.075 |

| MFC | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| 8 | MIC | 0.30 | 0.037 | 0.020 | 0.075 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.075 | 0.15 |

| MFC | 0.60 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.30 | |

| 9 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.05 | 0.020 | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.15 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.30 | |

| 10 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.15 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.037 | |

| 11 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.075 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.015 | |

| 12 | MIC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.05 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.075 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.15 | |

| 13 | MIC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.05 | 0.005 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.075 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.15 | |

| 14 | MIC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.05 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.075 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| 15 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.037 | |

| 16 | MIC | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.037 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.05 |

| MFC | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.075 | |

| 17 | MIC | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.037 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| 18 | MIC | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.10 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.15 |

| MFC | 0.037 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.037 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.30 | |

| 19 | MIC | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.015 |

| MFC | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.070 | 0.015 | 0.070 | 0.070 | 0.037 | |

| 20 | MIC | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.45 | 0.45 | |

| 21 | MIC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| 22 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.050 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.10 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.15 | |

| 23 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.015 | - | 0.037 | - | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.30 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.037 | - | 0.075 | - | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.45 | |

| 24 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.075 | 0.050 | 0.075 | 0.10 | 0.20 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.30 | |

| 25 | MIC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.10 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.45 | 0.45 | |

| 26 | MIC | 0.075 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.10 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.20 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.30 | |

| 27 | MIC | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| MFC | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.90 | 0.30 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 0.60 | |

| 28 | MIC | 0.037 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| MFC | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 | |

| 29 | MIC | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.05 | 0.020 | 0.050 |

| MFC | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.037 | |

| 30 | MIC | 2.40> | 0.60 | 1.20 | 2.40 | 0.20 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 1.20 |

| MFC | 2.40> | 1.20 | 1.80 | 2.40 | 0.30 | 1.20 | 0.60 | 2.40 | |

| 31 | MIC | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.60 | 0.15 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.60 |

| MFC | 1.80 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 1.20 | 0.30 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.80 | |

| Ketoconazole | MIC | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.20 |

| MFC | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.50 | 1.50 | 0.50 | 1.50 | 0.30 | |

| Bifonazole | MIC | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| MFC | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.20 | |

| N/N | Est. Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Binding Affinity Score E. coli MurB | I-H | Residues E. coli MurB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Topo IVPDB ID: 1S16 | E. coli Primase PDB ID: 1DDE | Gyrase PDB ID: 1KZN | Thymidylate Kinase PDB ID: 4QGG | E. coli MurB PDB ID: 2Q85 | ||||

| 1 | −5.02 | - | −7.22 | −2.88 | −9.12 | −31.47 | 1 | Ser228 |

| 2 | −4.96 | −1.86 | −7.03 | - | −8.73 | −30.54 | 2 | Tyr189, Asn232 |

| 3 | - | - | −6.14 | −2.01 | −8.45 | −29.48 | 2 | Asn232, Glu324 |

| 4 | −3.82 | −1.63 | −6.85 | - | −8.71 | −30.12 | 1 | Ser228 |

| 5 | −2.18 | - | −5.73 | −2.15 | −7.70 | −27.56 | 2 | Tyr124, Arg213 |

| 6 | - | - | - | - | −5.14 | −17.24 | - | - |

| 7 | - | - | −7.43 | - | −7.02 | −25.31 | 1 | Gly122 |

| 8 | −1.21 | - | −3.31 | - | −6.50 | −22.13 | 1 | Arg158 |

| 9 | - | - | −2.88 | - | −6.25 | −21.01 | 1 | Arg213 |

| 10 | −5.22 | −2.35 | −7.31 | −2.89 | −9.36 | −31.58 | 1 | Ser228 |

| 11 | −3.01 | - | −6.16 | −2.13 | −8.70 | −29.55 | 1 | Ser228 |

| 12 | - | - | - | −1.93 | −6.57 | −22.43 | 1 | Arg158 |

| 13 | −1.25 | - | −3.38 | - | −6.62 | −22.79 | 1 | Asn232 |

| 14 | - | −1.13 | −5.05 | - | −7.22 | −25.41 | 1 | Tyr189 |

| 15 | −2.31 | - | −5.02 | - | −7.71 | −27.58 | 2 | Arg213, Asn232 |

| 16 | −2.11 | - | −4.81 | - | −7.69 | −27.55 | 2 | Arg213, Asn232 |

| 17 | - | - | −2.87 | - | −6.22 | −21.00 | 1 | Arg213 |

| 18 | −3.55 | - | −2.31 | - | −6.03 | −19.25 | 1 | Asn232 |

| 19 | −5.24 | −2.88 | −7.36 | −2.63 | −9.62 | −31.89 | 1 | Ser228 |

| 20 | - | −1.32 | −4.16 | −1.29 | −7.51 | −26.31 | 1 | Asn232 |

| 21 | - | - | - | - | −5.21 | −18.92 | - | - |

| 22 | −1.25 | −2.96 | −6.08 | - | −8.11 | −28.74 | 1 | Ser228 |

| 23 | - | - | −4.88 | - | 7.53 | −26.42 | 1 | Arg213 |

| 24 | - | - | −3.52 | - | −6.85 | −24.16 | 1 | Arg213 |

| 25 | - | - | - | - | −4.71 | −15.03 | - | - |

| 26 | −2.63 | - | −6.22 | - | −8.13 | −28.74 | 1 | Ser228 |

| 27 | - | - | - | - | −3.29 | −11.24 | - | - |

| 28 | - | −1.23 | −6.23 | - | −8.27 | −28.96 | 1 | Ser228 |

| 29 | - | −1.96 | −5.27 | - | −7.23 | −25.44 | 1 | Gly122 |

| 30 | - | - | −6.05 | - | −8.24 | −28.53 | 1 | Ser228 |

| 31 | - | - | −1.09 | - | −1.02 | −3.64 | - | - |

| Com. | Est. Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Binding Affinity Score CYP51 of C. albicans PDB ID: 5V5Z | I-H | Residues CYP51 of C. albicans PDB ID: 5V5Z | Interaction with Heme | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squalene SynthasePDB ID:1EZF | Dihydrofolate ReductasePDB ID: 4HOF | CYP51 of C. albicans PDB ID: 5V5Z | ||||||

| 1 | −1.85 | −6.92 | −9.31 | −30.74 | 1 | Ser312 | Hem601 | |

| 2 | −4.21 | −7.60 | −26.19 | 2 | Tyr118, Ser312 | |||

| 3 | −3.02 | −7.66 | −9.79 | −32.86 | 1 | Tyr118 | Hem601 | |

| 4 | −6.11 | −8.64 | −28.19 | - | - | Hem601 | ||

| 5 | −5.73 | −7.91 | −26.28 | - | - | Hem601 | ||

| 6 | −6.32 | −22.41 | 1 | Tyr132 | ||||

| 7 | −3.85 | −7.13 | −26.04 | - | - | Hem601 | ||

| 8 | −3.33 | −7.01 | −25.97 | - | - | Hem601 | ||

| 9 | −1.06 | −6.30 | −8.73 | −28.41 | - | - | Hem601 | |

| 10 | −1.25 | −6.54 | −8.80 | −29.13 | - | - | Hem601 | |

| 11 | −3.25 | −7.45 | −9.72 | −32.67 | 1 | Tyr118 | Hem601 | |

| 12 | −5.88 | −8.32 | −27.53 | - | - | Hem601 | ||

| 13 | −4.12 | −9.01 | - | - | ||||

| 14 | −5.93 | −8.37 | −27.16 | - | - | Hem601 | ||

| 15 | −2.84 | −7.23 | −9.51 | −31.93 | - | - | Hem601 | |

| 16 | −1.86 | −6.95 | −9.33 | −30.82 | 1 | Ser312 | Hem601 | |

| 17 | −1.12 | −2.47 | −7.02 | −25.93 | - | - | Hem601 | |

| 18 | −4.22 | −7.66 | −26.21 | 2 | Tyr118, Ser312 | |||

| 19 | −3.11 | −8.01 | −10.06 | 34.16 | - | - | Hem601 | |

| 20 | −6.71 | −24.13 | 1 | Tyr118 | ||||

| 21 | −6.55 | −23.58 | 1 | Tyr118 | ||||

| 22 | −5.44 | −7.68 | −26.13 | 2 | Tyr118, Tyr132 | |||

| 23 | −3.21 | −7.12 | - | - | ||||

| 24 | −5.87 | −8.34 | −27.36 | - | - | Hem601 | ||

| 25 | −7.02 | −25.94 | - | - | Hem601 | |||

| 26 | −1.03 | −6.75 | −24.19 | - | - | Hem601 | ||

| 27 | −5.84 | −19.05 | - | - | ||||

| 28 | −3.25 | −8.17 | −11.25 | −34.58 | 1 | Tyr378 | Hem601 | |

| 29 | −3.10 | 6.33 | −8.81 | −29.16 | - | - | Hem601 | |

| 30 | −4.82 | −9.15 | - | - | ||||

| 31 | −1.59 | −5.37 | −11.28 | - | - | |||

| ketoconazole | - | −6.75 | −8.23 | −22.47 | 1 | Tyr64 | Hem601 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amiranashvili, L.; Nadaraia, N.; Merlani, M.; Kamoutsis, C.; Petrou, A.; Geronikaki, A.; Pogodin, P.; Druzhilovskiy, D.; Poroikov, V.; Ciric, A.; et al. Antimicrobial Activity of Nitrogen-Containing 5-α-Androstane Derivatives: In Silico and Experimental Studies. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9050224

Amiranashvili L, Nadaraia N, Merlani M, Kamoutsis C, Petrou A, Geronikaki A, Pogodin P, Druzhilovskiy D, Poroikov V, Ciric A, et al. Antimicrobial Activity of Nitrogen-Containing 5-α-Androstane Derivatives: In Silico and Experimental Studies. Antibiotics. 2020; 9(5):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9050224

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmiranashvili, Lela, Nanuli Nadaraia, Maia Merlani, Charalampos Kamoutsis, Anthi Petrou, Athina Geronikaki, Pavel Pogodin, Dmitry Druzhilovskiy, Vladimir Poroikov, Ana Ciric, and et al. 2020. "Antimicrobial Activity of Nitrogen-Containing 5-α-Androstane Derivatives: In Silico and Experimental Studies" Antibiotics 9, no. 5: 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9050224

APA StyleAmiranashvili, L., Nadaraia, N., Merlani, M., Kamoutsis, C., Petrou, A., Geronikaki, A., Pogodin, P., Druzhilovskiy, D., Poroikov, V., Ciric, A., Glamočlija, J., & Sokovic, M. (2020). Antimicrobial Activity of Nitrogen-Containing 5-α-Androstane Derivatives: In Silico and Experimental Studies. Antibiotics, 9(5), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9050224