Environmental Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Resistome-Based Comparison of Hospital and Community Wastewater Sources

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

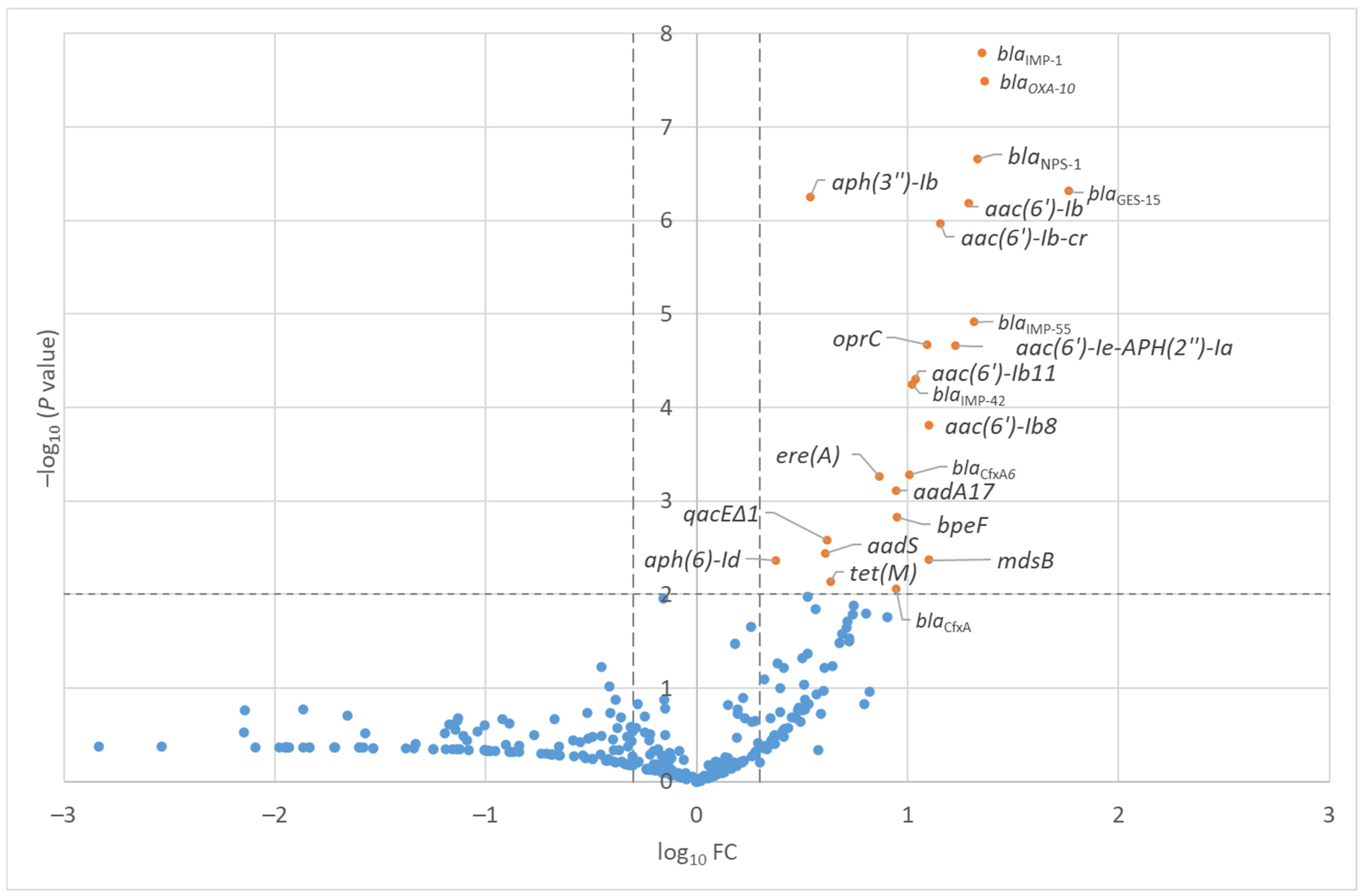

2.1. ARGs in the Wastewater Samples from the Hospital and Shopping Mall

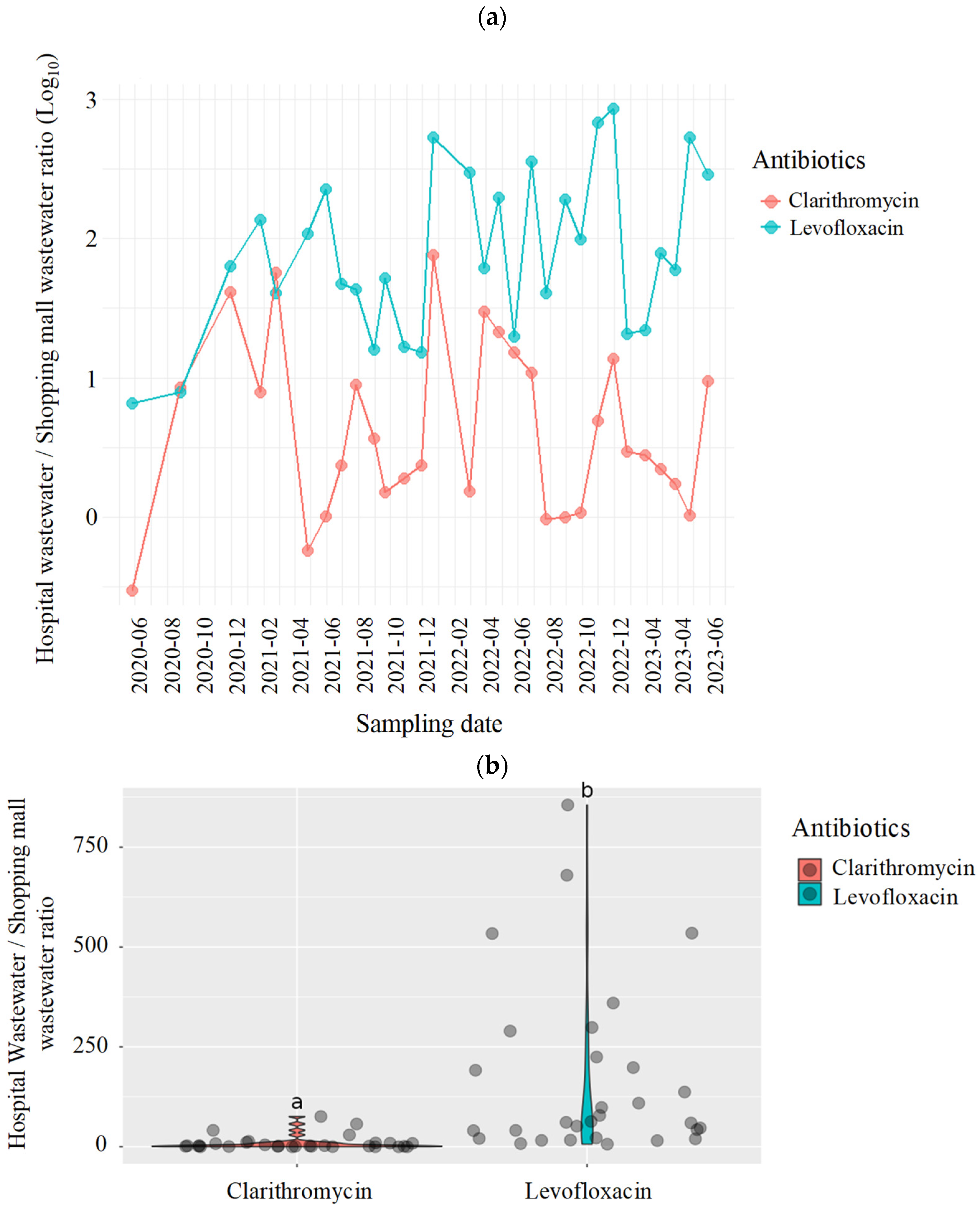

2.2. Antimicrobials in the Wastewater Samples from the Hospital and Shopping Mall

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Settings and Sample Collection

4.2. Antimicrobial Resistome Analysis

4.3. Evaluation of Residual Antimicrobial Concentrations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| ARG | Antimicrobial resistance gene |

| TLA | Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae |

| CRE | Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae |

| ESBL | Extended spectrum β-lactamase |

| FC | Fold change |

| NCGM | National Center for Global Health and Medicine |

| RPKM | reads per kilobase per million mapped reads |

| WBE | wastewater-based epidemiology |

References

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Khurshid, M.; Arshad, M.I.; Muzammil, S.; Rasool, M.; Yasmeen, N.; Shah, T.; Chaudhry, T.H.; Rasool, M.H.; Shahid, A.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance: One Health One World Outlook. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 771510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkman, A.; Do, T.T.; Walsh, F.; Virta, M.P.J. Antibiotic-Resistance Genes in Waste Water. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendonk, T.U.; Manaia, C.M.; Merlin, C.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Cytryn, E.; Walsh, F.; Buergmann, H.; Sørum, H.; Norström, M.; Pons, M.-N.; et al. Tackling antibiotic resistance: The environmental framework. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, D.I.; Hughes, D. Microbiological effects of sublethal levels of antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, A.G.; Vill, A.C.; Shi, Q.; Satlin, M.J.; Brito, I.L. Widespread transfer of mobile antibiotic resistance genes within individual gut microbiomes revealed through bacterial Hi-C. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, J.; Li, S.C. Understanding Horizontal Gene Transfer network in human gut microbiota. Gut Pathog. 2020, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun-Kheir, N.; Stabholz, Y.; Kreft, J.U.; de la Cruz, R.; Romalde, J.L.; Nesme, J.; Sørensen, S.J.; Smets, B.F.; Graham, D.; Paul, M. Comparison of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes abundance in hospital and community wastewater: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.D. The antibiotic resistome: The nexus of chemical and genetic diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Cha, C.J. Antibiotic resistome from the One-Health perspective: Understanding and controlling antimicrobial resistance transmission. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Chamorro, S.; Marti, E.; Huerta, B.; Gros, M.; Sànchez-Melsió, A.; Borrego, C.M.; Barceló, D.; Balcázar, J.L. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in hospital and urban wastewaters and their impact on the receiving river. Water Res. 2015, 69, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuma, T.; Matsunaga, N.; Ohmagari, N.; Kuroda, M. Development of a high-throughput analytical method for antimicrobials in wastewater using an automated pipetting and solid-phase extraction system. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Zheng, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, A.N.; Jiang, X.T.; Zhang, T. ARGs-OAP v3.0: Antibiotic-Resistance Gene Database Curation and Analysis Pipeline Optimization. Engineering 2023, 27, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, M.; Graham, D.W.; Ahammad, S.Z. Hospital Wastewater Releases of Carbapenem-Resistance Pathogens and Genes in Urban India. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 13906–13912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cheng, W.; Xu, L.; Strong, P.J.; Chen, H. Antibiotic-resistant genes and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the effluent of urban residential areas, hospitals, and a municipal wastewater treatment plant system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 4587–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Cao, Y.; Li, B. Hospital Wastewater as a Reservoir for Antibiotic Resistance Genes: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Public. Health 2020, 8, 574968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelow, E.; Bayjanov, J.R.; Majoor, E.; Willems, R.J.; Bonten, M.J.; Schmitt, H.; van Schaik, W. Limited influence of hospital wastewater on the microbiome and resistome of wastewater in a community sewerage system. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, N.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Cao, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, C. The microbiome, resistome, and their co-evolution in sewage at a hospital for infectious diseases in Shanghai, China. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0390023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Sun, J.; Yao, F.; Yuan, Y.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, X. Antimicrobial resistance bacteria and genes detected in hospital sewage provide valuable information in predicting clinical antimicrobial resistance. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talat, A.; Blake, K.S.; Dantas, G.; Khan, A.U. Metagenomic Insight into Microbiome and Antibiotic Resistance Genes of High Clinical Concern in Urban and Rural Hospital Wastewater of Northern India Origin: A Major Reservoir of Antimicrobial Resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0410222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, K.; Matsumoto, A.; Tetsuka, N.; Morioka, H.; Iguchi, M.; Ishiguro, N.; Nagamori, T.; Takahashi, S.; Saito, N.; Tokuda, K.; et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales infections in Japan. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 29, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, K.; Ogawa, M.; Sakata, R.; Kanamori, H. Epidemiological Characteristics of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Japan: A Nationwide Analysis of Data from a Clinical Laboratory Center (2016–2022). Pathogens 2023, 12, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamio, K.; Espinoza, J.L. The Predominance of Klebsiella aerogenes among Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Infections in Japan. Pathogens 2022, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayama, S.; Yahara, K.; Sugawara, Y.; Kawakami, S.; Kondo, K.; Zuo, H.; Kutsuno, S.; Kitamura, N.; Hirabayashi, A.; Kajihara, T.; et al. National genomic surveillance integrating standardized quantitative susceptibility testing clarifies antimicrobial resistance in Enterobacterales. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (JANIS). Clinical Laboratory Division. Annual Open Report 2022 (All Facilities). Available online: https://janis.mhlw.go.jp/english/report/open_report/2022/3/1/ken_Open_Report_Eng_202200_clsi2012.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Yuan, T.; Pian, Y. Hospital wastewater as hotspots for pathogenic microorganisms spread into aquatic environment: A review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1091734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, G.; Chaudhary, P.; Gangola, S.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, A.; Rafatullah, M.; Chen, S. A review on hospital wastewater treatment technologies: Current management practices and future prospects. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2023, 56, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J.; Flach, C.F. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.A.; Feyen, L.; Hübner, T.; Brüggemann, N.; Prost, K.; Grohmann, E. Fate of Horizontal-Gene-Transfer Markers and Beta-Lactamase Genes during Thermophilic Composting of Human Excreta. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.A.A.; Shin, W.S.; Septian, A.; Samaraweera, H.; Khan, I.J.; Mohamed, M.M.; Billah, M.M.; López-Maldonado, E.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; et al. Exploring the environmental pathways and challenges of fluoroquinolone antibiotics: A state-of-the-art review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Pratap, S.G.; Raj, A. Occurrence and dissemination of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in aquatic environment and its ecological implications: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 47505–47529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, A.; Zhang, X.; Dai, Y.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y. Occurrence and removal of quinolone, tetracycline, and macrolide antibiotics from urban wastewater in constructed wetlands. J. Clean. Product. 2020, 252, 119677. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.; Sui, M.; Qin, C.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhao, J. Migration, transformation and removal of macrolide antibiotics in the environment: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 26045–26062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaerts, T.; Van Wichelen, N.; Quireyns, M.; Burgard, D.; Bijlsma, L.; Delputte, P.; Gys, C.; Covaci, A.; van Nuijs, A.L.N. Current state and future perspectives on de facto population markers for normalization in wastewater-based epidemiology: A systematic literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 935, 173223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmiege, D.; Haselhoff, T.; Thomas, A.; Kraiselburd, I.; Meyer, F.; Moebus, S. Small-scale wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) for infectious diseases and antibiotic resistance: A scoping review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2024, 259, 114379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuma, T.; Katagiri, M.; Sasaki, N.; Kuroda, M.; Watanabe, M. Performance of a pilot-scale continuous flow ozone-based hospital wastewater treatment system. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Shukla, P.; Giri, B.S.; Chowdhary, P.; Chandra, R.; Gupta, P.; Pandey, A. Prevalence and hazardous impact of pharmaceutical and personal care products and antibiotics in environment: A review on emerging contaminants. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Zhao, K.; Song, G.; Zhao, S.; Liu, R. Risk control of antibiotics, antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) during sewage sludge treatment and disposal: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162772. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare (Japan). Japan Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (JANIS), Nosocomial Infections Surveillance for Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria. Available online: https://janis.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.asp (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare (Japan). Annual Report on Statistics of Production by Pharmaceutical Industry in 2021. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/105-1.html (accessed on 2 June 2025). (In Japanese)

- Azuma, T.; Nakano, T.; Koizumi, R.; Matsunaga, N.; Ohmagari, N.; Hayashi, T. Evaluation of the correspondence between the concentration of antimicrobials entering sewage treatment plant influent and the predicted concentration of antimicrobials using annual sales, shipping, and prescriptions data. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, T.; Usui, M.; Hayashi, T. Inactivation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in hospital wastewater by ozone-based advanced water treatment processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167432. [Google Scholar]

- Daughton, C.G. Pharmaceuticals and the Environment (PIE): Evolution and impact of the published literature revealed by bibliometric analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 562, 391–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Lee, D.; Cho, H.K.; Choi, S.D. Review of the quechers method for the analysis of organic pollutants: Persistent organic pollutants, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and pharmaceuticals. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2019, 22, e00063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.; Škrbić, B.; Živančev, J.; Ferrando-Climent, L.; Barcelo, D. Determination of 81 pharmaceutical drugs by high performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry with hybrid triple quadrupole–linear ion trap in different types of water in serbia. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 468–469, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Sui, Q.; Yu, X.; Zhao, W.; Li, Q.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Lyu, S. Identification of indicator ppcps in landfill leachates and livestock wastewaters using multi-residue analysis of 70 PPCPs: Analytical method development and application in Yangtze River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 753, 141653. [Google Scholar]

| Antimicrobial Class | Antimicrobial Resistant Gene | −log10(p) | log10(FC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactam | blaIMP-1 | 7.8 | 1.4 |

| β-lactam | blaOXA-10 | 7.5 | 1.4 |

| β-lactam | blaNPS-1 | 6.7 | 1.3 |

| β-lactam | blaGES-15 | 6.3 | 1.8 |

| Aminoglycoside | aph(3″)-Ib | 6.3 | 0.5 |

| Aminoglycoside | aac(6′)-Ib′ | 6.2 | 1.3 |

| Aminoglycoside | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 6.0 | 1.2 |

| β-lactam | blaIMP-55 | 4.9 | 1.3 |

| Multi-drug | oprC | 4.7 | 1.1 |

| Aminoglycoside | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia | 4.7 | 1.2 |

| Aminoglycoside | aac(6′)-Ib11 | 4.3 | 1.0 |

| β-lactam | blaIMP-42 | 4.2 | 1.0 |

| Aminoglycoside | aac(6′)-Ib8 | 3.8 | 1.1 |

| β-lactam | blaCfxA6 | 3.3 | 1.0 |

| Macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin | ere(A) | 3.3 | 0.9 |

| Aminoglycoside | aadA17 | 3.1 | 0.9 |

| Multi-drug | bpeF | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| Multi-drug | qacEΔ1 | 2.6 | 0.6 |

| Aminoglycoside | aadS | 2.4 | 0.6 |

| Multi-drug | mdsB | 2.4 | 1.1 |

| Aminoglycoside | aph(6)-Id | 2.4 | 0.4 |

| Tetracycline | tet(M) | 2.1 | 0.6 |

| β-lactam | blaCfxA | 2.1 | 0.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kitano, T.; Matsunaga, N.; Akiyama, T.; Azuma, T.; Fujii, N.; Tsukada, A.; Hibino, H.; Kuroda, M.; Ohmagari, N. Environmental Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Resistome-Based Comparison of Hospital and Community Wastewater Sources. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010099

Kitano T, Matsunaga N, Akiyama T, Azuma T, Fujii N, Tsukada A, Hibino H, Kuroda M, Ohmagari N. Environmental Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Resistome-Based Comparison of Hospital and Community Wastewater Sources. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleKitano, Taito, Nobuaki Matsunaga, Takayuki Akiyama, Takashi Azuma, Naoki Fujii, Ai Tsukada, Hiromi Hibino, Makoto Kuroda, and Norio Ohmagari. 2026. "Environmental Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Resistome-Based Comparison of Hospital and Community Wastewater Sources" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010099

APA StyleKitano, T., Matsunaga, N., Akiyama, T., Azuma, T., Fujii, N., Tsukada, A., Hibino, H., Kuroda, M., & Ohmagari, N. (2026). Environmental Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Resistome-Based Comparison of Hospital and Community Wastewater Sources. Antibiotics, 15(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010099