Policy Framework and Barriers in Antimicrobial Consumption Monitoring at the National Level: A Qualitative Study from Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Theme I: Perception About Antimicrobial Consumption, AWaRe Classification, and Related Terms

2.1.1. Perception About Antimicrobial Consumption and Antimicrobial Use

“There is a narrow difference. Antimicrobial consumption is used as an overall term for how many antimicrobials are imported in Pakistan, while utilization is the number of medicines or antimicrobials used in a hospital.”(Federal regulator-I)

“In my point of view, AMU and AMC are different. AMU is a rational use of antimicrobials, while AMC is the use of antimicrobials in your country. AMC is the consumption of antimicrobials in all aspects, whether it is legal or illegal.”(International health organization-I)

“I believe antimicrobial consumption and use are more or less the same, i.e., the total amount of antibiotics manufactured or imported in a country.”(Federal regulator-II)

“The use is the same as consumption; I don’t see any difference between the two.”(Manufacturer-III)

2.1.2. Antimicrobial Resistance

“AMR is the major problem. We further elaborate on the terms’ consumption’ and ‘utilization’ under AMR. Irrational use and self-medication are the primary drivers of this issue. Many superbugs are changing, which we knew during treatment.”(Pharmaceutical policy and practice expert-I)

2.1.3. AWaRe Classification

“WHO has an essential medicine list, which is used as it is without any amendment, and is approved by DRAP.”(Federal regulator-IV)

“I think that every country should adopt not just the WHO classification but its own form of classification, which should be assessed according to their needs, because resistant patterns are different. However, the WHO classification is helpful for the country as well as any region, for example, developing countries like Pakistan, which have limited resources.”(Federal regulator-III)

“Some physicians have no idea about AWaRe, and I don’t blame them for that, as they are not provided with any awareness about it. They have not been trained in any way, and this should be the responsibility of the provincial departments and the federal government.”(International health organization-I)

2.2. Theme II: Antimicrobial Consumption: Policy Design

2.2.1. Rules for Import and Manufacturing of Antimicrobials

“Sub rule 6 of rule 30 of Licensing, Registration and Advertising Rules under the Drug Act 1976, states that all the manufacturers that use API, will submit their consumption record quarterly on form 7 (L, R &A), and unfortunately, there is no implementation of that rule.”(Provincial regulator-III)

“Drug registering, licensing, and advertising are rules framed under the drug act 1976. It states that each manufacturing unit of medicines whose products are registered must provide import, export, and production records every 3 months. It is not implemented in the true spirit.”(Provincial regulator-V)

“DRAP has data on all anti-microbial drugs imported into Pakistan. The import and export section within the quality assurance and lab testing (QA<) division regulates the import and export of antimicrobial raw materials and finished products. DRAP is the authority primarily responsible for approving the import of health commodities by the public and private sectors, importers, individual organizations, and public institutions (e.g., hospitals, donor agencies, and research institutions). It issues all import permits for any medicine imported into the country. However, the consumption record of those antimicrobials is not always kept up-to-date.”(Federal regulator-IV)

“We obtain an import license before importing the antibiotics and a manufacturing license before formulating it. Similarly, the distribution and sale of drugs are regulated and conducted in accordance with the relevant regulations after obtaining the relevant license. However, we are not strictly asked to submit quarterly consumption.”(Manufacturer-II)

“We import antimicrobials to meet the demand of the market, and it is beneficial from a business point of view. Seasonal trends of specific antibiotics also exist. In winter, the sales and demand of antibiotics increase. We don’t have any import restrictions regarding the quantity of antibiotics”(Manufacturer-I)

“We follow rules, and we register drugs and import as per policy and submit the consumption reports quarterly. Inspectors visit to assess the quality of materials and ensure SOPs are followed during manufacturing. If quality is not maintained, the industry is fined and sealed by the inspector depending on the offense”(Manufacturer-III)

“Though we are bound to submit a quarterly consumption report, we usually don’t. Annual reports are submitted occasionally or when we need to import or export another consignment of drugs; we are also asked to report the consumption of the old import. In this way, the next consignment is cleared. However, unlike controlled drugs, there is no restriction on the amount of antibiotics we can import if we are registered for the specific drug.”

“Some antimicrobials used in the animal sector are imported as growth promoters, so these are imported without approval of DRAP. Moreover, the same antimicrobial is administered in various animals, and to calculate DDDs, we have to divide it by different animal weights for each type of animal and it is often not done.”(Federal regulator III)

2.2.2. Distribution and Sales: Legislation in Different Provinces of Pakistan

“Seven set rules regarding sales are implemented in our country, including all four provinces (Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Islamabad Capital Territory, AJK, and Gilgit Baltistan. There are two types of schedules in these rules. The important one is Schedule D of drug rules, which is implemented in Punjab, Islamabad, and KPK. There is a list of medicines in the schedule that may be sold only with a prescription, and you must maintain records of their sale. If these schedules are checked strictly, you can see that these schedules are not updated, so you can’t achieve results even after their 100% implementation.”(Federal regulator-I)

“There are the Drugs (Labeling and Packing) rules 1986, stating the medicines that fall in the schedules (schedule D) should be labeled ‘to be sold on the prescription of a registered medical practitioner (RMP) only’. We are deficient in both the implementation and legislative aspects.”(Provincial regulator-III)

“In Pakistan, mostly antibiotics are sold without a prescription. After a struggle of 3–4 years, we have controlled the sale of psychotropic and controlled drugs. Now, we can start working on antimicrobials to be sold only with a prescription.”(Federal regulator-IV)

“All the provinces have their regulatory bodies. There are no specific sales rules for the antibiotics in the provinces. The EML and schedules are not up-to-date, and many antibiotics are not included in the relevant schedules.”(Federal regulator-I)

“Both human and animal drugs are referred to as therapeutic drugs, and the distribution and consumption among the human and animal industries have the same laws.”(Provincial regulator-V)

“The rules that exist are not followed because of many issues. Many antibiotics are not part of the list of ‘sold on prescription only’. The rules and lists need amendments; we are working on it.”(Provincial regulator-V)

2.3. Theme III: Data Management and Record Keeping for the Estimation of Antimicrobial Consumption

2.3.1. Estimation of Consumption: Grounds for Human and Animal Consumption

“DRAP should play this role, they are working on this aspect to be more helpful as they are the major stakeholder.”(International health organization-IV)

“DRAP has a role in the registration of data. We have the import and export data here. The manufacturers have manufacturing and distribution records for finished products. Distributors have the data for further distribution of antimicrobials to retailers and community Pharmacies.”(Federal regulator-II)

“IQVIA takes data from distributions and a few private setups, as our government setups don’t have resources, training, and manpower to collect the data systematically”(International health organization-II)

“There are many methods; the one we have used till now is to document the international trade, meaning data from customs, import in animal and human health.”(Federal regulator-IV)

“We have import and export data of antimicrobials, but sometimes it is difficult to segregate human and animal data. A manufacturer can have a human and veterinary antimicrobial section under the same license, though the sections are separate. So, if they imported antimicrobials, it is difficult to segregate whether the antimicrobial was imported for human medicine or for veterinary medicine”(Federal regulator-V)

“Import and export data are documented in kilogram/units. In both the animal and human sectors, generic drugs are imported. Active ingredients are imported in kilograms. We haven’t reached the level to maintain data by route of administration. We compile the import and export data and keep it. Recently, we started segregating the data we receive by access watch and reserve groups. We don’t have further segregation.”(Federal regulator-III)

“After obtaining data, the next step is validation of that data, e.g., if ciprofloxacin is imported 40 tons, its manufacture and consumption don’t need to be according to the import; there will be a difference in the pattern of how it is utilized. We need to calculate the import data and report it, and simultaneously begin estimating the utilization pattern. For utilization, the process is not easy. We have to approach this at different levels within the government sector, such as what kinds of procurement executive district officer (EDOs), district health officers (DHOs), medical superintendent (MS), Tertiary care, and other offices can do. For now, it is not possible to obtain data from all sectors and every hospital, so we can start by selecting a few locations to collect data, and we have started with KPK. We haven’t started in other places till now because of a feasibility issue.”(International health organization-III)

2.3.2. In Animals (as Feed Grade and Growth Promoters)

“There are different ways of monitoring consumption. In animal health, there is a concept of using a raw material, a pure material, or an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). Few companies in Pakistan import antibiotics as nutritional products, calling them feed grade, and DRAP is not involved in it, as they are not directly labeled as antibiotics. I don’t know how consumption data is interpreted and evaluated internationally. Still, in Pakistan, I believe it cannot happen accurately; we cannot estimate consumption on similar grounds as humans, as in the animal sector, we have finished products very rarely.”(International health organization-IV)

“Only a sophisticated farm keeps the record of use. We struggled a lot and tried many ways, like installing trash cans and asking them to throw medicine-related trash into them. Every brand has almost 4,5 combinations of antimicrobials in one dosage form of medicine. In such a situation, calculating AMU becomes complicated. Those who maintain the record are not doing so because they have concerns about AMR; they have to keep a ledger of the amounts used from a business point of view.”(Academia animal health-I)

2.4. Theme IV: Levels of Estimation for Antimicrobial Consumption and Organizations

2.4.1. Responsibilities of Different Organizations for Controlling Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance as per the National Action Plan

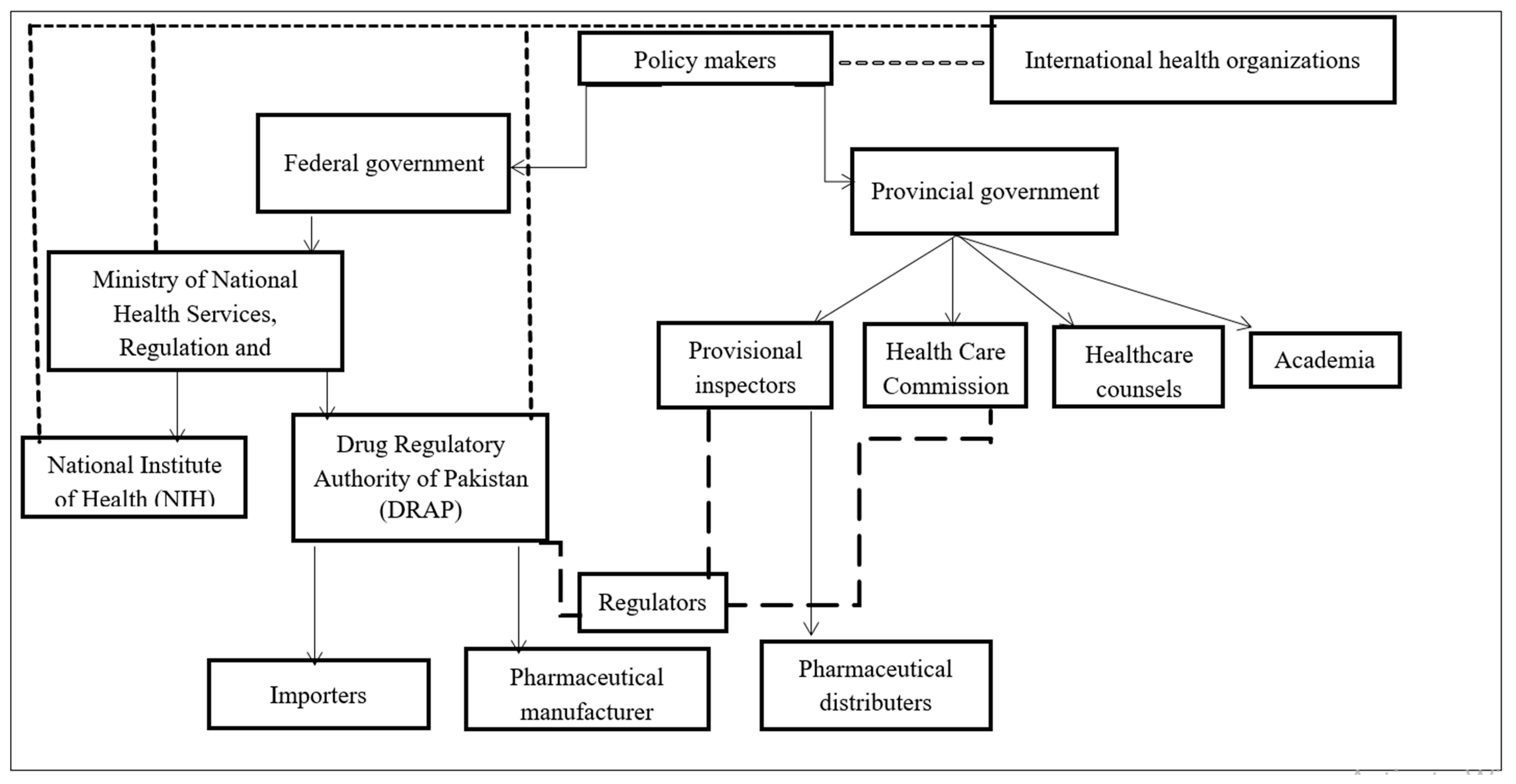

“Major focal point for AMR in Pakistan is NIH, which is working in collaboration with health departments, regulatory bodies, federal (DRAP), provincial), hospitals, and academia for controlling AMR. DRAP deals with the AMC component (the NIH’s role is collaborative), i.e., the import, manufacturing, distribution, and sale of antimicrobials. The mandate of international health organizations working in Pakistan is to collaborate with national and provisional bodies and assist them, such as providing training sessions, and other matters.”(Pharmaceutical policy and practice expert-I)

2.4.2. Software for Data Collection and Data Arrangement

“We have launched PIRISMS, for the licensing of pharmaceutical units. This will improve accountability and transparency. Once we shift it online, it will reduce the workload and give accurate trends of import and export of drugs.”(Federal regulator I)

“Our vision is that when we get the ultimate trend for the anti-microbial consumption data, we want to link it with the AMR pattern. With a linked resistance pattern, we can determine whether specific antimicrobials are required. This information will help medical professionals and other stakeholders.”(Federal regulator-II)

2.5. Theme V: Challenges and Suggested Solutions in Estimation of AMC: One Health Approach Is the Way Forward

2.5.1. Challenges

“Government organizations don’t have a proper system. Even in the organization, there is a conflict of opinion. Sometimes, availability and accessing data are issues, indicating a lack of proper systems and coordination among departments. Ideally, every province should have a system that compiles and reports data monthly, quarterly, and annually to the director general of health of the province; they then report it to the national organization, for example, in case of AMR to NIH & for AMC to DRAP. The national organizations should consolidate the data, generate an annual report on the country’s situation on that matter, and share it with the WHO for the GLASS report. In our country, data is not compiled regularly or on time, leading to missing data and broken links. We do not have institutionalization; we receive the data but lack the resources or methods to validate it. Sometimes we obtained data that is flawed to the point that carbapenems are not used on poultry, but the data will support their use, showing a major error.”(Federal regulator-1)

“Data reliability is a major issue, and gaps exist. Survey-based data has its own limitations. As we don’t have a system available, it’s better to have something than nothing. Some private organizations collect data, and the ways adopted to collect data lead to a question mark.”(Federal regulator-III)

“International organizations gave training. I believe they were not very fruitful. We need to understand that training should have a practical aspect rather than just bookish, repetitive knowledge. They should improve the training content. At our organizational level, we also offer interdepartmental training. But not much was about the AMC aspect.”(Federal regulator-II)

“For AMC, weak institutions in terms of federal regulatory authority, poor communication between provincial and federal authorities, and a lack of digitalization are the main problems. If customs can digitalize it through a single-window operation, why can’t the federal organization primarily responsible for AMC do the same? The transfer of officers responsible for AMC to other departments is another challenge. This makes it difficult to design a proper training.”(International health organization-I)

“Objectively speaking, lack of trust, miscommunication, or no communication at all are the primary reasons that lead to many problems. The government has power, and international organizations have funding. If they can sit and give credit where it’s due, it can help resolve many issues.”

“This is a developing country, money is an issue, and people work overtime to earn money. If you have money, you can hire more people & have a well-developed system.”(Provincial government-I)

“I agree, it is the weakness, and I believe it is a system failure, as we are unable to stop or restrict OTC sales of antibiotics. Realistically speaking, we are a developing country, and people are poor. To avoid physicians’ charges, they self-medicate or prefer the quacks, a cheaper solution. They visit qualified doctors or professionals only when the situation is worse, as the areas are remote and travelling costs a lot. We cannot change the situation overnight. It will take time, and I believe strict implementation of laws is the only solution”(Provincial government-II)

“The human health surveillance plan raises objections; it is too microbiology-oriented, and the epidemiology part is missing.”(Federal regulator-V)

“We need to check the use of pesticides and antibiotics in agriculture. People lack awareness of the issue’s sensitivity. Those pesticides enter the soil, contaminating the environment and the food consumed by humans and animals. It is a vicious cycle.”(Agriculture-I)

2.5.2. Suggested Solutions

“The best solution is to change our behavior; we should change ourselves rather than trying to change others. The government also needs to implement strict rules on self-medication with antibiotics. Strict implementation of laws and reviewing the old rules to close the loopholes are the solution.”(Academia pharmacy-II)

“As you know, DRAP wrote the generic letter, which states that no physician is allowed to write the antimicrobials with brand names and only use the generic name so that misuse of antibiotics can be prevented. Even physicians cannot differentiate between antibiotic brands, and they suggest two different brands without realizing that both are the same. DRAP is pressing hard on the provinces to sit together with the secretary of health, the Healthcare Commission, and other relevant authorities of the provinces and agree on a common point not to give any antibiotics without a prescription and dispense only in the presence of a pharmacist.”(Pharmaceutical policy and practice expert-I)

“In the past, we invited 2 to 3 people from every province to the headquarters, but now we have planned to go to each province to train and guide them. I am now responsible for organizing the AMC and AMS awareness campaign, and I have written letters to all provinces to maintain records of antimicrobial drug data. We aim to educate the doctors, nurses, pharmacists, pathologists, and medical lab technicians.”(Federal regulator-III)

“Development of user-friendly software that could be used while offline as well is mandatory. As Pakistan is a developing country, and all the provinces or areas do not have a smooth internet connection.”(Provincial regulator-III)

“Educate the medical students and pharmacy students about AMR, international guidelines, AWaRe classification may be one of the solutions.”(Academia medicine-1)

“Regulation of sales of antimicrobials is the responsibility of DRAP or provincial drug inspectors. Our work is to make sure the clinics have qualified doctors. Ensuring the presence of a pharmacist at pharmacies is the responsibility of drug inspectors. However, we are trying our best.”(Healthcare Commission-I)

“We did a few surveys whose results are under process of compilation. We will share our results with veterinary drug prescribers and provide recommendations. We forward our recommendations only after we have results based on evidence.”(International organization-II)

“Currently, we have launched the AMS programme for veterinary drugs. Surveillance programmes and AMS should be implemented in both the human and animal sectors”(International health organization-I)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Interview Schema Development

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMC | Antimicrobial Consumption |

| AMS | Antimicrobial Stewardship |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| API | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient |

| AWaRe | Access, Watch, Reserve |

| COREQ | Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| DRAP | Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| GLASS | Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System |

| KPK | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |

| NIH | National Institute of Health |

| OTC | Over the Counter |

| PIRIMS | Pakistan Integrated Regulatory Information Management System |

| PQM | Promoting the quality of medicine |

| RMP | Register Medical Practitioner |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| LMICs | Low and Middle Income Countries |

References

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 2015, 109, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, S.; Sisay, M.; Mengistu, G.; Amare, F.; Edessa, D. Antimicrobial utilization pattern in pediatric patients in tertiary care hospital, Eastern Ethiopia: The need for antimicrobial stewardship. Hosp. Pharm. 2018, 53, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Khan, R.; Khalid, K.; Chong, C.; Bakhtiar, A. Correlation between antibiotic consumption and the occurrence of multidrug-resistant organisms in a Malaysian tertiary hospital: A 3-year observational study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romandini, A.; Pani, A.; Schenardi, P.A.; Pattarino, G.A.C.; De Giacomo, C.; Scaglione, F. Antibiotic resistance in pediatric infections: Global emerging threats, predicting the near future. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinto, E.J.; Caro, I.; Villalobos-Delgado, L.H.; Mateo, J.; De-Mateo-Silleras, B.; Redondo-Del-Río, M.P. food safety through natural antimicrobials. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. CDC: 1 in 3 Antibiotic Prescriptions Unnecessary. Available online: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/media/releases/2016/p0503-unnecessary-prescriptions.html (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- WHO. WHO Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on Surveillance of Antibiotic Consumption: 2016–2018 Early Implementation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Badau, E. A one health perspective on the issue of the antibiotic resistance. Parasite 2021, 28, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Guo, Z.; Ai, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Cao, C.; Xu, J.; Xia, S.; Zhou, X.-N.; Chen, J.; et al. Establishment of an indicator framework for global One health intrinsic drivers index based on the grounded theory and fuzzy analytical hierarchy-entropy weight method. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2022, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charani, E.; Mendelson, M.; Pallett, S.J.C.; Ahmad, R.; Mpundu, M.; Mbamalu, O.; Bonaconsa, C.; Nampoothiri, V.; Singh, S.; Peiffer-Smadja, N.; et al. An analysis of existing national action plans for antimicrobial resistance—Gaps and opportunities in strategies optimising antibiotic use in human populations. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e466–e474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Z.; Godman, B.; Azhar, F.; Kalungia, A.C.; Fadare, J.; Opanga, S.; Markovic-Pekovic, V.; Hoxha, I.; Saeed, A.; Al-Gethamy, M.; et al. Progress on the national action plan of Pakistan on antimicrobial resistance (AMR): A narrative review and the implications. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharland, M.; Gandra, S.; Huttner, B.; Moja, L.; Pulcini, C.; Zeng, M.; Mendelson, M.; Cappello, B.; Cooke, G.; Magrini, N. Encouraging aware-ness and discouraging inappropriate antibiotic use-the new 2019 essential medicines list becomes a global antibiotic stewardship tool. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1278–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Aware Classification of Antibiotics for Evaluation and Monitoring of Use; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Ajaleh, S.; Darwish Elhajji, F.; Al-Bsoul, S.; Abu Farha, R.; Al-Hammouri, F.; Amer, A.; Al Rusasi, A.; Al-Azzam, S.; Araydah, M.; Aldeyab, M.A. An evaluation of the impact of increasing the awareness of the WHO access, watch, and reserve (aware) antibiotics classification on knowledge, attitudes, and hospital antibiotic prescribing practices. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A. Manual of Drug Laws (as Amended Upto Date); Mansoor Law Book House: Karachi, Pakistan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiga, I.; Pitchforth, E.; Stålsby Lundborg, C.; Machowska, A. Family doctors’ roles and perceptions on antibiotic consumption and antibiotic resistance in Romania: A qualitative study. BMC Prim. Care 2023, 24, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Ana-Tellez, Y.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K.; Leufkens, H.G.; Wirtz, V.J. Effects of over-the-counter sales restriction of antibiotics on substitution with medicines for symptoms relief of cold in Mexico and Brazil: Time series analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid Aziz, M.; Haider, F.; Rasool, M.F.; Hashmi, F.K.; Bahsir, S.; Li, P.; Zhao, M.; Alshammary, T.M.; Fang, Y. Dispensing of non-prescribed antibiotics from community pharmacies of Pakistan: A cross-sectional survey of pharmacy staff’s opinion. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Ihsan, B.; Malik, I.; Ahmad, N.; Saleem, Z.; Sehar, A.; Babar, Z.U. Antibiotic stewardship program in Pakistan: A multicenter qualitative study exploring medical doctors’ knowledge, perception and practices. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, H.A.; Babar, Z.-U.-D.; Hussain, I.M. A leap towards enforcing medicines prescribing by generic names in low- and middle-income countries (LMICS): Pitfalls, limitations, and recommendations for local drug regulatory agencies. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2022, 15, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, A.; Elnour, A.A.; Ali, A.A.; Hassan, N.A.; Shehab, A.; Bhagavathula, A.S. Evaluation of rational use of medicines (rum) in four government hospitals in uae. Saudi Pharm. J. 2016, 24, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G.; Kotwani, A.; Bhullar, L.; Joshi, J. Over-the-counter sales of antibiotics for human use in India: The challenges and opportunities for regulation. Med. Law Int. 2021, 21, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckernan, C.; Benson, T.; Farrell, S.; Dean, M. Antimicrobial use in agriculture: Critical review of the factors influencing behaviour. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goutard, F.L.; Bordier, M.; Calba, C.; Erlacher-Vindel, E.; Góchez, D.; De Balogh, K.; Benigno, C.; Kalpravidh, W.; Roger, F.; Vong, S. Antimicrobial policy interventions in food animal production in South East Asia. BMJ 2017, 358, j3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankhomwa, J.; Tolhurst, R.; M’biya, E.; Chikowe, I.; Banda, P.; Mussa, J.; Mwasikakata, H.; Simpson, V.; Feasey, N.; Macpherson, E.E. A qualitative study of antibiotic use practices in intensive small-scale farming in urban and peri-urban Blantyre, Malawi: Implications for antimicrobial resistance. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 876513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Ivanovska, V.; Schweickert, B.; Muller, A. Proxy indicators for antibiotic consumption; surveillance needed to control antimicrobial resistance. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 3-3A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, C.M.; De Kraker, M.E.A.; Harbarth, S. Surveillance of resistance to new antibiotics in an era of limited treatment options. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 652638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etikan, I. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; And Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

indicates a direct connection and impact of stakeholders with respect to AMC,

indicates a direct connection and impact of stakeholders with respect to AMC,  works in mutual interest (indicates aligned interest however not directly affected),

works in mutual interest (indicates aligned interest however not directly affected),  indicates regulators from different disciplines however connected (involved in AMU and AMC).

indicates regulators from different disciplines however connected (involved in AMU and AMC).

indicates a direct connection and impact of stakeholders with respect to AMC,

indicates a direct connection and impact of stakeholders with respect to AMC,  works in mutual interest (indicates aligned interest however not directly affected),

works in mutual interest (indicates aligned interest however not directly affected),  indicates regulators from different disciplines however connected (involved in AMU and AMC).

indicates regulators from different disciplines however connected (involved in AMU and AMC).

| Type of Institution | Sector | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Health | Animal Health | ||||

| Academia | Medicine | Nursing | Pharmacy | ||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |

| Federal government | 8 | 8 | |||

| Provincial government | 5 | 5 | |||

| Pharmaceutical policy and practice expert | 1 | 1 | |||

| International organizations | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| Manufacturers/Importers | 5 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Healthcare Commission | 3 | -- | 3 | ||

| Total | 31 | 6 | 37 * | ||

| Details | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Profession | |

| Doctor (MBBS) | 8 |

| Veterinary doctor | 4 |

| Pharmacist | 19 |

| Nurse | 2 |

| Distributor/Manufacturer | 4 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 29 |

| Female | 8 |

| Age | |

| <40 | 15 |

| 40–60 | 18 |

| >60 | 4 |

| Experience (years) | |

| <5 | 3 |

| 5–10 | 10 |

| 10–20 | 14 |

| 20+ | 10 |

| Levels of Estimation of AMC | Levels of Estimation of AMU |

|---|---|

| Customs data | Retail pharmacies |

| Import data from DRAP | Hospitals (private and public sector) |

| Manufacturers | Private clinics |

| Distributors |

| Organization | Major Stakeholder | Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| DRAP | AMC |

|

| NIH | AMR |

|

| International health organization (not a major stakeholder, but assists) | AMR, AMC, AMU |

|

| Provincial government | Distribution and sale of drugs |

Limited resources for the estimation of AMC

|

| Too much focus on the microbial resistance aspect instead of AMC (2) |

| Less communication between provincial and federal authorities (4) |

Lack of training sessions

|

| Lack of IT software Lack of digitalization (provincial) (11) |

Legislative Issues (Lack of legislation and its implementation)

|

Improving and implementing existing legislations

|

Capacity building programs

|

Development of user-friendly software that could be used while offline

|

Mapping of the antibiotic supply chain and keeping records in both the human and animal sectors

|

One Health Approach

|

| Mass Awareness campaigns (27) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ihsan, B.; Iqbal, S.M.; Aufy, M.; Jamil, Q. Policy Framework and Barriers in Antimicrobial Consumption Monitoring at the National Level: A Qualitative Study from Pakistan. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010089

Ihsan B, Iqbal SM, Aufy M, Jamil Q. Policy Framework and Barriers in Antimicrobial Consumption Monitoring at the National Level: A Qualitative Study from Pakistan. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleIhsan, Beenish, Shahid Muhammad Iqbal, Mohammed Aufy, and QurratulAin Jamil. 2026. "Policy Framework and Barriers in Antimicrobial Consumption Monitoring at the National Level: A Qualitative Study from Pakistan" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010089

APA StyleIhsan, B., Iqbal, S. M., Aufy, M., & Jamil, Q. (2026). Policy Framework and Barriers in Antimicrobial Consumption Monitoring at the National Level: A Qualitative Study from Pakistan. Antibiotics, 15(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010089