One Health Perspective on Antimicrobial Resistance in Bovine Mastitis Pathogens—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Etiology of Bovine Mastitis

3. Antimicrobials Used to Treat Bovine Mastitis

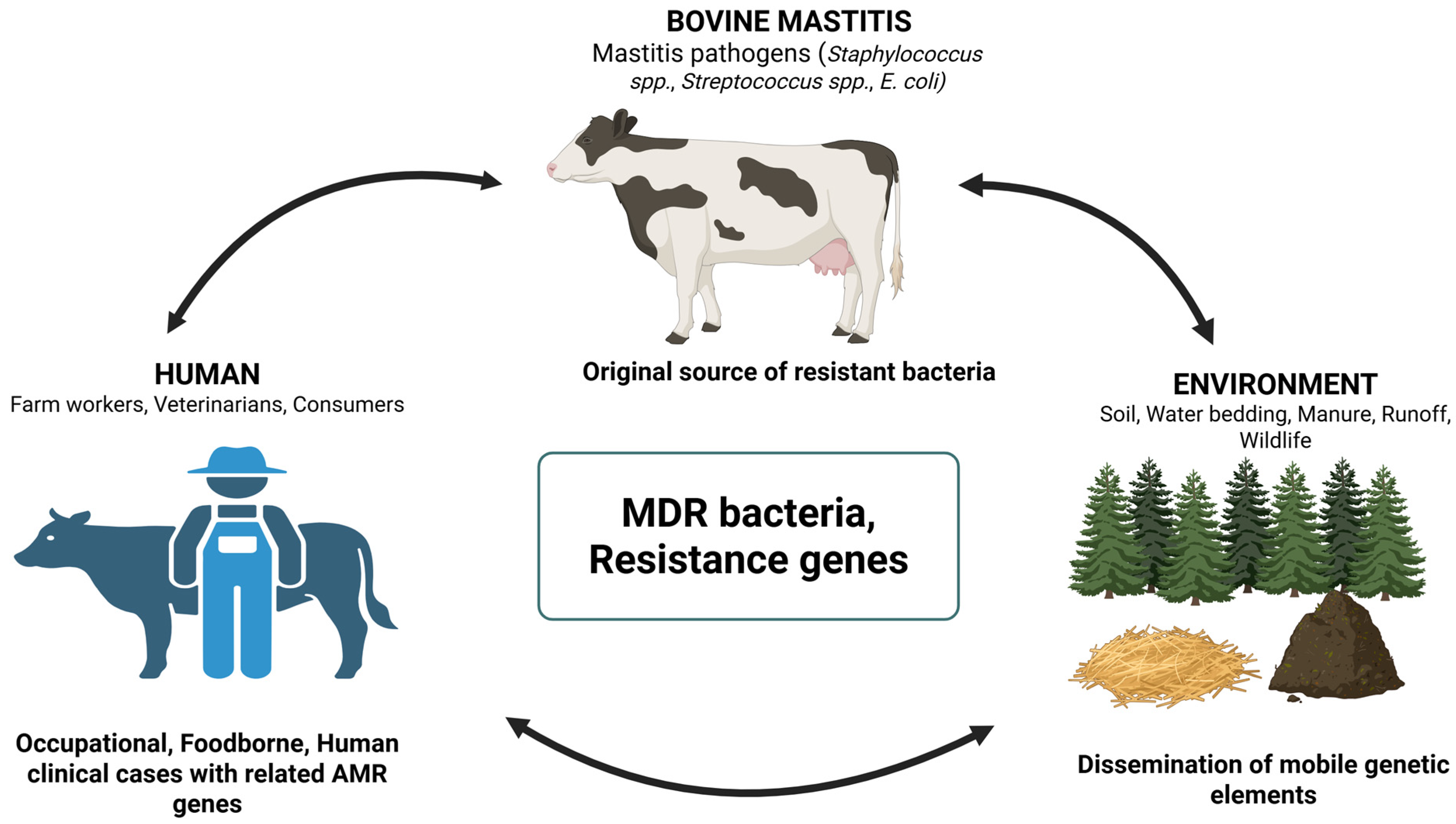

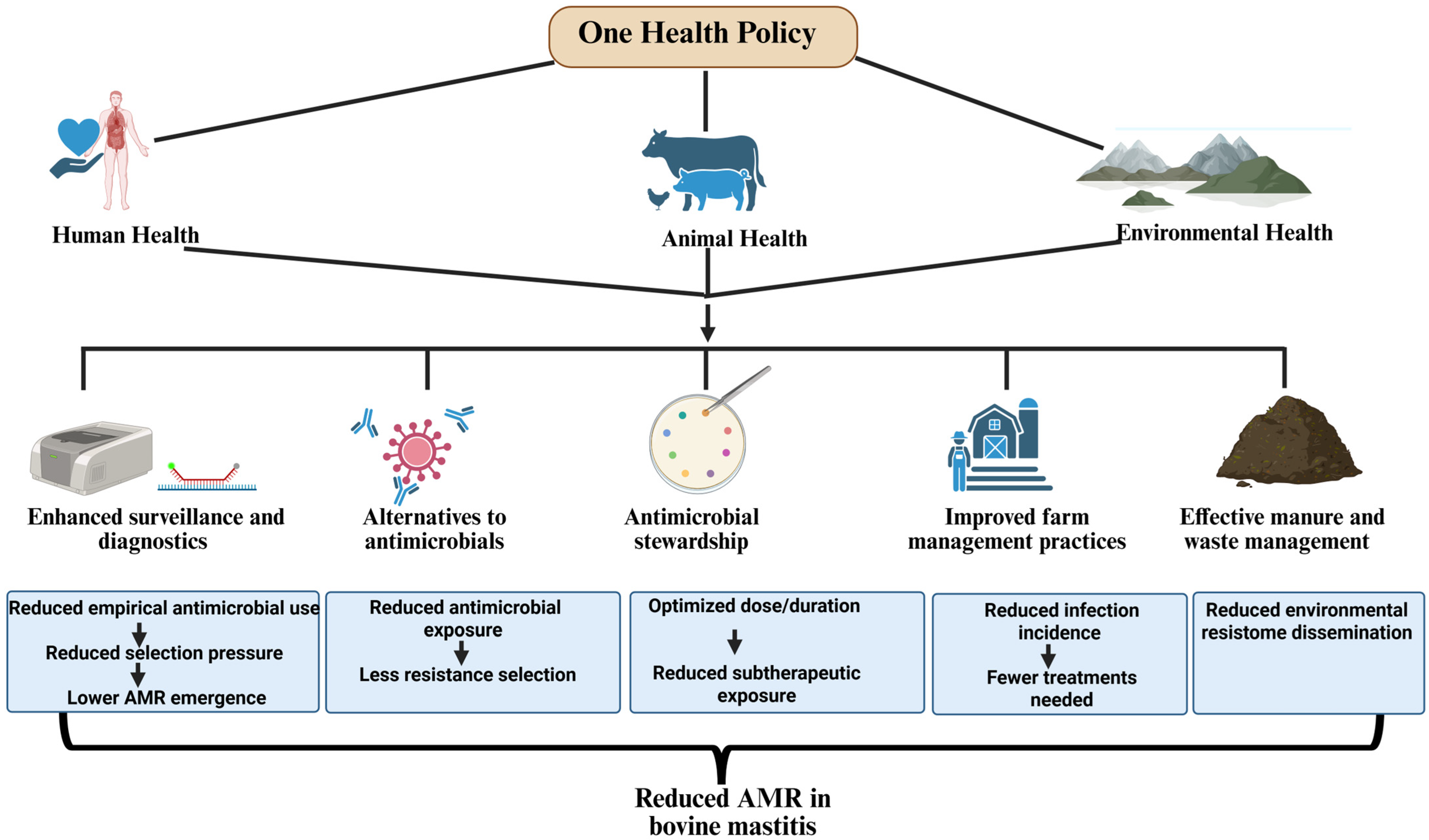

4. A One Health Perspective

4.1. Antimicrobial Resistance in Bovine Mastitis Pathogens

4.2. Zoonotic and Public Health Implications

4.3. Environmental Reservoirs of AMR

5. Integrated One Health Policies to Mitigate AMR in Bovine Mastitis Pathogens

5.1. Enhanced Surveillance and Diagnostics

5.2. Alternatives to Antimicrobials

5.3. Antimicrobial Stewardship

5.4. Improved Farm Management Practices

5.5. Effective Manure and Waste Management

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stanek, P.; Żółkiewski, P.; Januś, E. A review on mastitis in dairy cows research: Current status and future perspectives. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, P.; Barkema, H.W.; Osei, P.P.; Taylor, J.; Shaw, A.P.; Conrady, B.; Chaters, G.; Muñoz, V.; Hall, D.C.; Apenteng, O.O.; et al. Global losses due to dairy cattle diseases: A comorbidity-adjusted economic analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 6945–6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogeveen, H.; Steeneveld, W.; Wolf, C.A. Production diseases reduce the efficiency of dairy production: A review of the results, methods, and approaches regarding the economics of mastitis. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2019, 11, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.N.; Han, S.G. Bovine mastitis: Risk factors, therapeutic strategies, and alternative treatments—A review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 33, 1699–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasivam, R.; Gopal, D.R.; Dhandapani, R.; Subbarayalu, R.; Elangovan, M.P.; Prabhu, B.; Veerappan, V.; Nandheeswaran, A.; Paramasivam, S.; Muthupandian, S. Is AMR in dairy products a threat to human health? An updated review on the origin, prevention, treatment, and economic impacts of subclinical mastitis. Infect. Drug. Resist. 2023, 16, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Qi, Y. Prevalence of clinical mastitis and its associated risk factors among dairy cattle in mainland China during 1982–2022: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1185995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ATAER Global. The Economic Impact of Mastitis on Dairy Farming. ATAER Global—Official Distributor of AntiMastitor. 2025. Available online: https://ataerglobal.com/the-economic-impact-of-mastitis-on-dairy-farming/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Zhao, X.; Lacasse, P. Mammary tissue damage during bovine mastitis: Causes and control. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabelitz, T.; Aubry, E.; van Vorst, K.; Amon, T.; Fulde, M. The role of Streptococcus spp. in bovine mastitis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egyedy, A.F.; Ametaj, B.N. Mastitis: Impact of dry period, pathogens, and immune responses on etiopathogenesis of disease and its association with periparturient diseases. Dairy 2022, 3, 881–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Barkema, H.; Brito, L.; Narayana, S.; Miglior, F. Symposium review: Novel strategies to genetically improve mastitis resistance in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 2724–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonestroo, J.; Fall, N.; Hogeveen, H.; Emanuelson, U.; Klaas, I.C.; van der Voort, M. The costs of chronic mastitis: A simulation study of an automatic milking system farm. Prev. Vet. Med. 2023, 210, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupczyński, R.; Bednarski, M.; Sokołowski, M.; Kowalkowski, W.; Pacyga, K. Comparison of antibiotic use and the frequency of diseases depending on the size of herd and the type of cattle breeding. Animals 2024, 14, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xu, C.; Liang, B.; Kastelic, J.P.; Han, B.; Tong, X.; Gao, J. Alternatives to antibiotics for treatment of mastitis in dairy cows. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1160350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaatout, N.; Ayachi, A.; Kecha, M. Staphylococcus aureus persistence properties associated with bovine mastitis and alternative therapeutic modalities. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 1102–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, E.A.; Fazal, M.A.; Alim, M.A. Frequently used therapeutic antimicrobials and their resistance patterns on Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli in mastitis affected lactating cows. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2022, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, A.; Godden, S.M.; Bey, R.; Ruegg, P.L.; Leslie, K. The selective treatment of clinical mastitis based on on-farm culture results: I. Effects on antibiotic use, milk withholding time, and short-term clinical and bacteriological out-comes. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 4441–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, M.M.S.; Dubenczuk, F.C.; Melo, D.A.; Holmström, T.C.N.; Mendes, M.B.; Reinoso, E.B.; Coelho, S.M.O.; Coelho, I.S. Antimicrobial therapy approaches in the mastitis control driven by one health insights. Braz. J. Vet. Med. 2024, 46, e002624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). One Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Galarde-López, M.; Carrillo-Quiróz, B.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Antimicrobial resistance: One Health approach. Vet. World 2022, 15, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Nickerson, R.; Zhang, W.; Peng, X.; Shang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, Q.; Wen, G.; Cheng, Z. The impacts of animal agriculture on One Health—Bacterial zoonosis, antimicrobial resistance, and beyond. One Health 2024, 18, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, S.A.; Collignon, P.J. Antimicrobial resistance: A One Health perspective. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, A.; Bernabucci, U.; Nardone, A.; Lacetera, N. Effect of season, month, and temperature-humidity index on the occurrence of clinical mastitis in dairy heifers. Adv. Anim. Biosci. 2016, 7, 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitz, J.; Wente, N.; Zhang, Y.; Klocke, D.; Tho Seeth, M.; Krömker, V. Dry period or early lactation—Time of onset and associated risk factors for intramammary infections in dairy cows. Pathogens 2021, 10, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordillo, L.M. Mammary gland immunobiology and resistance to mastitis. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2018, 34, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sordillo, L.M. Factors affecting mammary gland immunity and mastitis susceptibility. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 98, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, X.; Nan, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Yao, J.; Xiong, B. Nutrition, gastrointestinal microorganisms and metabolites in mastitis occurrence and control. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 17, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ubaldo, A.L.; Rivero-Perez, N.; Valladares-Carranza, B.; Velázquez-Ordoñez, V.; Delgadillo-Ruiz, L.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A. Bovine mastitis, a worldwide impact disease: Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and viable alternative approaches. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2023, 21, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, B.; Chuang, S.T.; Hsieh, J.C.; Hsieh, M.H.; Chiang, H.I. Prevalence, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance of major mastitis pathogens isolated from Taiwanese dairy farms. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Takemoto, N.; Ogura, K.; Miyoshi-Akiyama, T. Severe invasive streptococcal infection by Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadoks, R.N.; Middleton, J.R.; McDougall, S.; Katholm, J.; Schukken, Y.H. Molecular epidemiology of mastitis pathogens of dairy cattle and comparative relevance to humans. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2011, 16, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobirka, M.; Tancin, V.; Slama, P. Epidemiology and classification of mastitis. Animals 2020, 10, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasapane, N.G.; Byaruhanga, C.; Thekisoe, O.; Nkhebenyane, S.J.; Khumalo, Z.T.H. Prevalence of subclinical mastitis, its associated bacterial isolates and risk factors among cattle in Africa: A systematic review and me-ta-analysis. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Guo, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, F.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bian, Y.; Tian, G.; Wu, C.; Cui, Q.; et al. Major causative bacteria of dairy cow mastitis in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, China, 2015–2024: An Epidemiologic Survey and Analysis. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, P.; Suresh, K.P.; Jayamma, K.S.; Shome, B.R.; Patil, S.S.; Amachawadi, R.G. An understanding of the global status of major bacterial pathogens of milk concerning bovine mastitis: A systematic review and metanalysis (Scientometrics). Pathogens 2021, 10, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, B.; Chen, Y.T.; Paudyal, S.; Pudasaini, R.; Chen, Y.T.; Chiang, H.I. Genomic signatures of beta-lactam resistance and reversion in Staphylococcus aureus from bovine mastitis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 78, ovaf107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, V.; McClure, J.T.; Léger, D.; Keefe, G.P.; Scholl, D.T.; Morck, D.W.; Barkema, H.W. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of common mastitis pathogens on Canadian dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 4319–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.S.; Hossain, H.; Rahman, M.N.; Rahman, A.; Ghosh, P.K.; Uddin, M.B.; Nazmul Hoque, M.; Hossain, M.M.; Rahman, M.M. Emergence of highly virulent multidrug and extensively drug resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in buffalo subclinical mastitis cases. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Shenawy, F.A. Bovine Mastitis: Pathogen factors and antibiotic-resistant genes “Article Review”. Egypt. J. Anim. Health 2024, 4, 220–237. [Google Scholar]

- Matheou, A.; Abousetta, A.; Pascoe, A.P.; Papakostopoulos, D.; Charalambous, L.; Panagi, S.; Panagiotou, S.; Yiallouris, A.; Filippou, C.; Johnson, E.O. Antibiotic use in livestock farming: A driver of multidrug resistance? Microorganisms 2025, 13, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J. Bovine immunology: Implications for dairy cattle. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 643206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovinen, M.; Pyörälä, S. Udder health of dairy cows in automatic milking. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mramba, R.P.; Mohamed, M.A. The prevalence and factors associated with mastitis in dairy cows kept by small-scale farmers in Dodoma, Tanzania. Heliyon 2024, 10, E34122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Angel, C.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Roche, S.M.; Ritter, C. A focus group study of Canadian dairy farmers’ attitudes and social referents on antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 645221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, H.; Barkema, H.W.; Jacques, M.; Lavallée-Bourget, E.-M’.; Malouin, F.; Saini, V.; Stryhn, H.; Dufour, S. Invited review: Incidence, risk factors, and effects of clinical mastitis recurrence in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4729–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolhouse, M.; Ward, M.; vanBunnik, B.; Farrar, J. Antimicrobial resistance in humans, livestock and the wider environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilm, J.; Svennesen, L.; Kirkeby, C.; Krömker, V. Treatment of clinically severe bovine mastitis—A scoping review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1286461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmund, M.; Egger-Danner, C.; Firth, C.L.; Obritzhauser, W.; Roch, F.F.; Conrady, B.; Wittek, T. The effect of antibiotic versus no treatment at dry-off on udder health and milk yield in subsequent lactation: A retrospective analysis of Austrian health recording data from dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidović, J.; Stojanović, D.; Cagnardi, P.; Kladar, N.; Horvat, O.; Ćirković, I.; Bijelić, K.; Stojanac, N.; Kovačević, Z. Farm animal veterinarians’ knowledge and attitudes toward antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial use in the Republic of Serbia. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomanić, D.; Samardžija, M.; Kovačević, Z. Alternatives to antimicrobial treatment in bovine mastitis therapy: A review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosain, M.Z.; Kabir, S.M.L.; Kamal, M.M. Antimicrobial uses for livestock production in developing countries. Vet. World 2021, 14, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, T.A.; Birhanu, A.G. Antibiotic use in livestock and environmental antibiotic resistance: A narrative review. Environ. Health Insights 2025, 19, 11786302251357775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preine, F.; Herrera, D.; Scherpenzeel, C.; Kalmus, P.; McCoy, F.; Smulski, S.; Rajala-Schultz, P.; Schmenger, A.; Moroni, P.; Krömker, V. Different European Perspectives on the treatment of clinical mastitis in lactation. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krukowski, H.; Bakuła, Z.; Iskra, M.; Olender, A.; Bis-Wencel, H.; Jagielski, T. The first outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in dairy cattle in Poland with evidence of on-farm and intrahousehold transmission. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 10577–10584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbehiry, A.; Marzouk, E. From Farm to Fork: Antimicrobial-resistant bacterial pathogens in livestock production and the food chain. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasapane, N.G.; de Smidt, O.; Lekota, K.E.; Nkhebenyane, J.; Thekisoe, O.; Ramatla, T. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence determinants of Escherichia coli isolates from raw milk of dairy cows with subclinical mastitis. Animals 2025, 15, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massella, E.; Russo, S.; Filippi, A.; Garbarino, C.A.; Ricchi, M.; Bassi, P.; Toschi, E.; Torreggiani, C.; Pupillo, G.; Rugna, G.; et al. Does bovine raw milk represent a potential risk for vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) transmission to humans? Antibiotics 2025, 14, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesso, L.; Vanzetti, T.; Weber, J.; Vaccani, M.; Riva Scettrini, P.; Sartori, C.; Ivanovic, I.; Romanò, A.; Bodmer, M.; Bacciarini, L.N.; et al. District-wide herd sanitation and eradication of intramammary Staphylococcus aureus genotype B infection in dairy herds in Ticino, Switzerland. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 8299–8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, L.C.B.; Gouvêa, F.L.R.; Latosinski, G.S.; Fabri, F.H.H.; Salvador, T.B.; Guimaraes, F.F.; Ribeiro, M.G.; Langoni, H.; Rall, V.L.M.; Hernandes, R.T.; et al. Species diversity and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Enterococcus spp. isolated from mastitis cases, milking machine and the environment of dairy cows. Lett. Appl. MicroBiol. 2022, 75, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrah, A.; Zhang, D.; Darvishzadeh, P.; LaPointe, G. The contribution of dairy bedding and silage to the dissemination of genes coding for antimicrobial resistance: A narrative review. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhász-Kaszanyitzky, E.; Jánosi, S.; Somogyi, P.; Dán, A.; van der Graaf-van Bloois, L.; van Duijkeren, E.; Wagenaar, J.A. MRSA transmission between cows and humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 630–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, M.; Saab, M.; Heider, L.; McClure, J.T.; Rodriguez-Lecompte, J.C.; Sanchez, J. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of environmental streptococci recovered from bovine milk samples in the maritime provinces of Canada. Front. Vet. Sci. 2016, 3, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wente, N.; Krömker, V. Streptococcus dysgalactiae-Contagious or Environmental? Animals 2020, 10, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murinda, S.E.; Ibekwe, A.M.; Rodriguez, N.G.; Quiroz, K.L.; Mujica, A.P.; Osmon, K. Shiga Toxin–producing Escherichia coli in mastitis: An international perspective. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2019, 16, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, R.; Hatiya, H.; Abera, M.; Megersa, B.; Asmare, K. Bovine mastitis: Prevalence, risk factors, and isolation of Staphylococcus aureus in dairy herds at Hawassa milk shed, South Ethiopia. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarba, E.J.; Tola, G.K. Cross-sectional study on bovine mastitis and its associated risk factors in Ambo district of West Shewa zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Vet. World 2017, 10, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Antibiotic Use on, U.S. Dairy Operations, 2002 and 2007; October 2008. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/dairy07_is_antibioticuse.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Doehring, C.; Sundrum, A. The informative value of an overview on antibiotic consumption, treatment efficacy, and cost of clinical mastitis at farm level. Prev. Vet. Med. 2019, 165, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHM). Dairy 2014 Report 2: Milk Quality Milking Procedures Mastitis on, U.S. Dairies, 2014; September 2016. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/dairy14_dr_mastitis.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Okello, E.; ElAshmawy, W.R.; Williams, D.R.; Lehenbauer, T.W.; Aly, S.S. Effect of dry cow therapy on antimicrobial resistance of mastitis pathogens post-calving. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1132810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, A.K.; Bhardwaj, R.; Mishra, P.; Rajput, S.K. Antimicrobials misuse/overuse: Adverse effect, mechanism, challenges, and strategies to combat resistance. Open Biotechnol. J. 2020, 14, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molineri, A.I.; Camussone, C.; Zbrun, M.V.; Suárez Archilla, G.; Cristiani, M.; Neder, V.; Calvinho, L.; Signorini, M. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 188, 105261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemzadeh, S.; Korneeva, O.; Shabunin, S.; Syromyatnikov, M. Antibiotic resistance in mastitis-causing bacteria: Exploring antibiotic-resistance genes, underlying mechanisms, and their implications for dairy animal and public health. Open Vet. J. 2025, 15, 3980–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, R.; Cosandey, A.; Luini, M.; Artursson, K.; Bardiau, M.; Breitenwieser, F.; Hehenberger, E.; Lam, T.; Mansfeld, M.; Michel, A.; et al. Bovine Staphylococcus aureus: Subtyping, evolution, and zoonotic transfer. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holko, I.; Tančin, V.; Vršková, M.; Tvarožková, K. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of udder pathogens isolated from dairy cows in Slovakia. J. Dairy Res. 2019, 86, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Kong, L.; Gao, H.; Cheng, X.; Wang, X. A review of current bacterial resistance to antibiotics in food animals. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 822689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, I.D.; Nicholson, J.K. Gut microbiome interactions with drug metabolism, efficacy, and toxicity. Transl. Res. 2017, 179, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine of Ireland, Agri-Food and Bioscience Institute, and Animal Health Ireland (DAFM, AFBI, and AHI). All-Island Animal Disease Surveillance Report 2020, DAFM, Dublin, Ireland; 24 December 2021. Available online: https://www.animalhealthsurveillance.agriculture.gov.ie/media/animalhealthsurveillance/content/labreports/SurveillanceReport2020.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Baumgartner, M.; Štromerová, N.H.; Bzdil, J.; Siegwalt, G. Susceptibility and resistance of selected pathogens of the mammary gland of cattle from Austria and Czech Republic in 2017. In Proceedings of the XVIII Middle-European Buiatrics Congress and XXVIII International Congress of the Hungarian Association for Buiatrics, Eger, Hungary, 30 May–2 June 2018; pp. 3448–3453. [Google Scholar]

- Chehabi, C.N.; Nonnemann, B.; Astrup, L.B.; Farre, M.; Pedersen, K. In vitro antimicrobial resistance of causative agents to clinical mastitis in Danish Dairy cows. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2019, 16, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, G.; Zhang, B.; Luo, Z.; Lu, B.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Z.; Shen, L.; et al. Molecular typing and prevalence of antibiotic resistance and virulence genes in Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from Chinese dairy cows with clinical mastitis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Behiry, A.; Schlenker, G.; Szabo, I.; Roesler, U. In vitro susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from cows with subclinical mastitis to different antimicrobial agents. J. Vet. Sci. 2012, 13, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelam Jain, V.K.; Singh, M.; Joshi, V.G.; Chhabra, R.; Singh, K.; Rana, Y.S. Virulence and antimicrobial resistance gene profiles of Staphylococcus aureus associated with clinical mastitis in cattle. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbindyo, C.M.; Gitao, G.C.; Plummer, P.J.; Kulohoma, B.W.; Mulei, C.M.; Bett, R. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and genes of Staphylococci Isolated from mastitic cow’s milk in Kenya. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suojala, L.; Pohjanvirta, T.; Simojoki, H.; Myllyniemi, A.L.; Pitkälä, A.; Pelkonen, S.; Pyörälä, S. Phylogeny, virulence factors, and antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli isolated in clinical bovine mastitis. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 147, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BVL. Resistenzsituation bei Klinisch Wichtigen Tierpathogenen Bakterien. German Resistance Monitoring, Vet. ORCA Affairs. 2018. Available online: https://www.bvl.bund.de/SharedDocs/Berichte/07_Resistenzmonitoringstudie/Bericht_Resistenzmonitoring_2018.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=7 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Yang, J.; Xiong, Y.; Barkema, H.W.; Tong, X.; Lin, Y.; Deng, Z.; Kastelic, J.P.; Nobrega, D.B.; Wang, Y.; Han, B.; et al. Comparative genomic analyses of Klebsiella pneumoniae K57 capsule serotypes isolated from bovine mastitis in China. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 3114–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duse, A.; Persson-Waller, K.; Pedersen, K. Microbial aetiology, antibiotic susceptibility and pathogen-specific risk factors for udder pathogens from clinical mastitis in dairy cows. Animals 2021, 11, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomanić, D.; Kladar, N.; Kovačević, Z. Antibiotic residues in milk as a consequence of mastitis treatment: Balancing animal welfare and one health risks. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.C.; Chowdhury, T.; Hossain, M.T.; Hasan, M.M.; Zahran, E.; Rahman, M.M.; Zinnah, K.M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Hossain, F.M.A. Zoonotic linkage and environmental contamination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in dairy farms: A One Health perspective. One Health 2024, 18, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Ambatipudi, K. Mammary microbial dysbiosis leads to the zoonosis of bovine mastitis: A One-Health perspective. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 97, fiaa241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoek, A.H.; Mevius, D.; Guerra, B.; Mullany, P.; Roberts, A.P.; Aarts, H.J. Acquired antibiotic resistance genes: An overview. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, H.; Schmitt, H.; Smalla, K. Antibiotic resistance gene spread due to manure application on agricultural fields. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyi-Loh, C.E.; Mamphweli, S.N.; Meyer, E.L.; Makaka, G.; Simon, M.; Okoh, A.I. An overview of the control of bacterial pathogens in cattle manure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meçaj, R.; Muça, G.; Koleci, X.; Sulçe, M.; Turmalaj, L.; Zalla, P.; Anita Koni, A.; Tafaj, M. Bovine environmental mastitis and their control: An overview. Int. J. Agric. Biosci. 2023, 12, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoaib, M.; Tang, M.; Aqib, A.I.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Wen, Y.; Pu, W. Dairy farm waste: A potential reservoir of diverse antibiotic resistance and virulence genes in aminoglycoside-and beta-lactam-resistant Escherichia coli in Gansu Province, China. Environ. Res. 2024, 263, 120190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, B.; Cornaggia, M.; Sabatino, R.; Di Cesare, A.; Furlan, M.; Barco, L.; Orsini, M.; Cordioli, B.; Mantovani, C.; Bano, L.; et al. Calves as main reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes in dairy farms. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 918658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, M.F.; Gomez, A.P.; Ceballos-Garzon, A. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Staphylococcus isolated from cows with subclinical mastitis: Do strains from the environment and from humans contribute to the dissemination of resistance among bacteria on dairy farms in Colombia? Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.R.; Kwong, S.M.; Firth, N.; Jensen, S.O. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, e00088-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinthong, W.; Pumipuntu, N.; Santajit, S.; Kulpeanprasit, S.; Buranasinsup, S.; Sookrung, N.; Chaicumpa, W.; Aiumurai, P.; Indrawattana, N. Detection and drug resistance profile of Escherichia coli from subclinical mastitis cows and water supply in dairy farms in Saraburi Province, Thailand. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piessens, V.; De Vliegher, S.; Verbist, B.; Braem, G.; Van Nuffel, A.; De Vuyst, L.; Heyndrickx, M.; Van Coillie, E. Characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococcus species from cows’ milk and environment based on bap, icaA, and mecA genes and phenotypic susceptibility to antimicrobials and teat dips. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 7027–7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.; Kock, M.M.; Ehlers, M.M. Diversity and antimicrobial susceptibility profiling of staphylococci isolated from bovine mastitis cases and close human contacts. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 6256–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizauro, L.J.L.; de Almeida, C.C.; Soltes, G.A.; Slavic, D.; de Ávila, F.A.; Zafalon, L.F.; MacInnes, J.I. Detection of antibiotic resistance, mecA, and virulence genes in coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. from buffalo milk and the milking environment. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 11459–11464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.N.; Osburn, B.I.; Cullor, J.S. A one health perspective on dairy production and dairy food safety. One Health 2019, 7, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.; Domingues, S.; Da Silva, G.J. Manure as a potential hotspot for antibiotic resistance dissemination by horizontal gene transfer events. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, C.; Rokana, N.; Chandra, M.; Singh, B.P.; Gulhane, R.D.; Gill, J.P.S.; Ray, P.; Puniya, A.K.; Panwar, H. Antimicrobial resistance: Its surveillance, impact, and alternative management strategies in dairy animals. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 4, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, E.; Giovanetti, M.; Benedetti, F.; Scarpa, F.; Johnston, C.; Borsetti, A.; Ceccarelli, G.; Azarian, T.; Zella, D.; Ciccozzi, M. Joining forces against antibiotic resistance: The One Health solution. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, D.; Uskoković, V.; Wakil, A.M.; Goni, Y.; Yusof, N.Y. Current and future technologies for the detection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.W.; Cha, C.N.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, M.J.; Park, J.Y.; Yoo, C.Y.; Son, S.E.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.J. Therapeutic effect of oregano essential oil on subclinical bovine mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Korean J. Vet. Res. 2015, 55, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, F.; Mancini, S.; Turchi, B.; Friscia, E.; Pistelli, L.; Giusti, G.; Cerri, D. A novel interpretation of the fractional inhibitory concentration index: The case Origanum vulgare L. and Leptospermum scoparium J. R. et G. Forst essential oils against Staphylococcus aureus strains. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 195, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.S.; Lee, E.B.; Hsu, W.H.; Suk, K.; Sayem, S.A.J.; Ullah, H.M.A.; Lee, S.J.; Park, S.C. Probiotics and postbiotics as an alternative to antibiotics: An emphasis on pigs. Pathogens 2023, 12, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdeva, A.; Tomar, T.; Malik, T.; Bains, A.; Karnwal, A. Exploring probiotics as a sustainable alternative to antimicrobial growth promoters: Mechanisms and benefits in animal health. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 8, 1523678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainard, P.; Gilbert, F.B.; Germon, P.; Foucras, G. A critical appraisal of mastitis vaccines for dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 10427–10448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Gao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Bacteriophage cocktails protect dairy cows against mastitis caused by drug-resistant Escherichia coli infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 690377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federman, C.; Joo, J.; Almario, J.A.; Salaheen, S.; Biswas, D. Citrus-derived oil inhibits Staphylococcus aureus growth and alters its interactions with bovine mammary cells. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 3667–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerioli, M.F.; Moliva, M.V.; Cariddi, L.N.; Reinoso, E.B. Effect of the essential oil of Minthostachys verticillata (Griseb.) Epling and limonene on biofilm production in pathogens causing bovine mastitis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesiak, B.; Kołodziej, B.; Głowacka, A.; Krukowski, H. The effect of some natural essential oils against bovine mastitis caused by Prototheca zopfii isolates in vitro. Mycopathologia 2018, 183, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeloengan, M. The effect of red ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) extract on the growth of mastitis-causing bacterial isolates. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2011, 5, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; He, X.R.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Zhao, H.Y.; Zheng, W.X.; Jiang, S.T.; Zhou, Q.; Li, P.P.; Han, S.Y. Taraxacum mongolicum extract induced endoplasmic reticulum stress associated-apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 206, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, B.J.; Zhao, P.; Li, H.T.; Sang, R.; Wang, M.; Zhou, H.Y.; Zhang, X.M. Taraxacum mongolicum protects against Staphylococcus aureus-infected mastitis by exerting an anti-inflammatory role via TLR2-NF-κB/MAPKs pathways in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 268, 113595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, P.M.; Smith, B.S.; Stewart, W.K.; Gonzalez, R.N.; Rubino, S.D.; Gusik, S.A.; Kulisek, E.S.; Projan, S.J.; Blackburn, P. Evaluation of a nisin-based germicidal formulation on teat skin of live cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1992, 75, 3185–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Shrivastava, S.; Singh, R.J.; Gogoi, P.; Saxena, S.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, N.; Gaur, G.K. Synthetic antimicrobial peptide Polybia MP-1 (mastoparan) inhibits growth of antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from mastitic cow milk. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2021, 27, 2471–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Shrivastava, S.; Gogoi, P.; Saxena, S.; Srivastava, S.; Singh, R.J.; Godara, B.; Kumar, N.; Gaur, G.K. Wasp venom peptide (Polybia MP-1) shows antimicrobial activity against multi drug resistant bacteria isolated from mastitic cow milk. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2022, 28, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacasse, P.; Lauzon, K.; Diarra, M.S.; Petitclerc, D. Utilization of lactoferrin to fight antibiotic-resistant mammary gland pathogens. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, N.; Capucchio, M.T.; Biasibetti, E.; Pessione, E.; Cirrincione, S.; Giraudo, L.; Corona, A.; Dosio, F. Antimicrobial activity of lactoferrin-related peptides and applications in human and veterinary medicine. Molecules 2016, 21, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, J.J.; Pacan, J.C.; Carson, M.E.; Leslie, K.E.; Griffiths, M.W.; Sabour, P.M. Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of bacteriophage therapy in treatment of subclinical Staphylococcus aureus mastitis in lactating dairy cattle. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2912–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schukken, Y.H.; Günther, J.; Fitzpatrick, J.; Fontaine, M.C.; Goetze, L.; Holst, O.; Leigh, J.; Petzl, W.; Schuberth, H.J.; Sipka, A.; et al. Host-response patterns of intramammary infections in dairy cows. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2014, 144, 270–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, X. Advances in vaccines against bovine mastitis. Vet. Res. 2022, 53, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y.C.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, X.M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, D.R.; Gao, S.; Qi, Z. Impact of yeast and lactic acid bacteria on mastitis and milk microbiota composition of dairy cows. AMB Express 2020, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakawa, M.; Zhuang, T.; Sato, H.; Takanashi, S.; Yoshimura, K.; Endo, Y.; Katsura, T.; Umino, T.; Tanaka, K.; Watanabe, H.; et al. Prevention of mastitis in multiparous dairy cows with a previous history of mastitis by oral feeding with probiotic Bacillus subtilis. Anim. Sci. J. 2022, 93, e13764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta, O.A.; Carrasco, C.; Vieytes, C.; Tamayo, M.J.; Muñoz, I.; Sepulveda, S.; Tadich, T.; Duchens, M.; Melendez, P.; Mella, A.; et al. Safety and efficacy of a mesenchymal stem cell intramammary therapy in dairy cows with experimentally induced Staphylococcus aureus clinical mastitis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Saini, S.; Ansari, S.; Verma, V.; Chopra, S.; Sharma, V.; Devi, P.; Malakar, D. Allogenic umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells are more effective than antibiotics in alleviating subclinical mastitis in dairy cows. Theriogenology 2022, 187, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Wang, X.; Chen, D.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shao, L.; Huang, L.; et al. Enhanced treatment effects of tilmicosin against Staphylococcus aureus cow mastitis by self-assembly sodium alginate-chitosan nanogel. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; Ammar, A.M.; El-Naenaeey, E.Y.M.; El Damaty, H.M.; Elazazy, A.A.; Hefny, A.A.; Shaker, A.; Eldesoukey, I.E. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm potentials of cinnamon oil and silver nanoparticles against Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from bovine mastitis: New avenues for countering resistance. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, S.; Davidson, L.E. Antimicrobial stewardship. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011, 86, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, S.J.; McAloon, C.; Silva Boloña, P.; O’Grady, L.; O’Sullivan, F.; McGrath, M.; Buckley, W.; Downing, K.; Kelly, P.; Ryan, E.G.; et al. Mastitis control and intramammary antimicrobial stewardship in Ireland: Challenges and opportunities. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 748353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruegg, P.L. The future of udder health: Antimicrobial stewardship and alternative therapy of bovine mastitis. JDS Commun. 2025, 6, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerton, F.; Russell, J. Antimicrobial stewardship in veterinary medicine: A review of online resources. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 5, dlad058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neculai-Valeanu, A.S.; Ariton, A.M.; Radu, C.; Porosnicu, I.; Sanduleanu, C.; Amariții, G. From herd health to public health: Digital tools for combating antibiotic resistance in dairy farms. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadse, S.N.; Ugemuge, S.; Singh, C. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship on reducing antimicrobial resistance. Cureus 2023, 15, e49935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, T.J.; van den Borne, B.H.; Jansen, J.; Huijps, K.; van Veersen, J.C.; van Schaik, G.; Hogeveen, H. Improving bovine udder health: A national mastitis control program in the Netherlands. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kic, P. Influence of technological housing conditions on the concentration of airborne dust in dairy farms in the summer: A case study. Animals 2023, 13, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaka, P.; Chantziaras, I.; Vijay, D.; Bedi, J.S.; Makovska, I.; Biebaut, E.; Dewulf, J. Can improved farm biosecurity reduce the need for antimicrobials in food animals? A scoping review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marutescu, L.G.; Jaga, M.; Postolache, C.; Barbuceanu, F.; Milita, N.M.; Romascu, L.M.; Schmitt, H.; de Roda Husman, A.M.; Sefeedpari, P.; Glaeser, S.; et al. Insights into the impact of manure on the environmental antibiotic residues and resistance pool. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 965132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Williams, A.D.; Hooton, S.P.; Helliwell, R.; King, E.; Dodsworth, T.; Baena-Nogueras, R.M.; Warry, A.; Ortori, C.A.; Todman, H.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance in dairy slurry tanks: A critical point for measurement and control. Environ. Int. 2022, 169, 107516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmaissa, M.; Zouari-Mechichi, H.; Sciara, G.; Record, E.; Mechichi, T. Pollution from livestock farming antibiotics an emerging environmental and human health concern: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 13, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katada, S.; Fukuda, A.; Nakajima, C.; Suzuki, Y.; Azuma, T.; Takei, A.; Takada, H.; Okamoto, E.; Kato, T.; Tamura, Y.; et al. Aerobic composting and anaerobic digestion decrease the copy numbers of antibiotic-resistant genes and the levels of lactose-degrading Enterobacteriaceae in dairy farms in Hokkaido, Japan. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 737420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pathogen | Study Year | Dairy Cows | Human Health | Environmental | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2018 | Mastitis cases confirmed in multiple dairy cows. | Identical MRSA S. aureus strains detected in milker, veterinarian, and household members. | MRSA detected on farm equipment and surfaces, indicating environmental persistence. | First reported MRSA outbreak in Polish dairy cattle; demonstrates on-farm and human transmission, highlighting One Health risks. | [45] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2002–2004 | Common mastitis pathogen with β-lactam resistance; MRSA identified in dairy herds. | Documented evidence of MRSA isolated from both cows with mastitis and farm workers. | MRSA detected in bedding, on milking equipment, and in dust/air on farms. | Phenotypic/genotypic matching indicates probable direct transmission between cows and a human worker. | [61] |

| Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Lactococcus spp., and Enterococcus spp. | 2007–2008 | Widespread resistance among isolates causing bovine mastitis. | Opportunistic human infections reported; shared resistance genes with human streptococci. | Survives in bedding, manure, soil, and water on dairy farms. | Reduced beta-lactam susceptibility observed in some regions. | [62] |

| Streptococcus dysgalactiae | 2020 | Different resistance levels. | NA | Either cow-associated or environmentally associated mastitis pathogen; may persist on dairy farms for more than one year. | Shows mixed transmission patterns in dairy herds, with evidence of both contagious spread and environmental persistence across farms. | [63] |

| Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, and Staphylococcus aureus | 2024 | Emerging mastitis agent with MDR isolates reported. Widespread resistance among isolates. | Resistant isolates can cause severe human infections if transmitted. | Found in bedding, water, and manure; spreads in the farm environment. | Serious threats in mastitis management. | [55,56] |

| Escherichia coli | 2019–2025 | MDR E. coli commonly recovered from mastitis milk; resistance genes. | Presence of similar resistance genes in isolates from dairy workers; potential for foodborne exposure via raw milk. | Detected in manure, farm runoff, and soils; ARG persistence documented on farms. | Genomic resistome/virulome analysis shows shared resistance genes; suggests reservoir potential. | [40,64] |

| Enterococcus spp. | 2017–2018 | Isolated from mastitis milk samples; species-specific distribution among milk, feces, and milking equipment. | Important opportunistic human pathogens; vancomycin-resistant enterococci are a major public health concern. | Widely distributed in feces, bedding, water, aisles, and milking equipment. | Showed species-specific niche distribution across milk, feces, and farm environments. | [59] |

| Enterococcus spp. | 2022–2024 | Mastitis isolates often carry van resistance genes. | vanC genes detected in raw bovine milk, suggesting possible transmission route from dairy to humans. | NA | Evidence of plasmid-mediated sharing of resistance determinants between animal and human isolates. | [57] |

| Pathogens | Country | Year | DISC or MIC | Resistance to Different Antimicrobials (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus uberis | Ireland | 2020 | DISC | Erythromycin (15.2%), Pirlimycin (22.2%), Tetracycline (11.5%) | [78] |

| Austria | 2017 | DISC | Penicillin (2.0%) | [79] | |

| Streptococcus spp. | Denmark | 2016 | MIC | Erythromycin (6.6%), Streptomycin (98.4%), Tetracycline (21.3%), Trimethoprim (1.6%) | [80] |

| Taiwan | 2020–2021 | DISC | Tetracycline (86.30%), Neomycin (79.45%), Bacitracin (38.35%), Ampicillin (45.20%), Oxacillin (73.97%), Cefuroxime (19.17%), Cephalothin (8.21%), Ceftiofur (26.02%). | [29] | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | China | 2017–2019 | DISC | Streptomycin (24.8%), Piperacillin (29.5%), Ceftriaxone (98.1%), penicillin (98.1%), Amoxicillin (98.1%), Ceftazidime (98.1%), | [81] |

| Staphylococcus spp. | Germany | 2012 | DISC | Penicillin (74.28%), Gentamycin (10%), and Tetracycline (7.14%). | [82] |

| Slovakia | 2015–2016 | DISC | Penicillin (5.9%), Oxacillin (14.4%), Lincomycin (4.8%), Neomycin (20.9%), Streptomycin (36.4%). | [75] | |

| Taiwan | 2020–2021 | DISC | Tetracycline (59.37%), Neomycin (21.87%), Bacitracin (34.37%), Ampicillin (43.75%), Oxacillin (53.12%), | [29] | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | India | 2021 | DISC | Penicillin (83.64%), Cefuroxime (21.82%), Amikacin (58.18%), Gentamicin (34.55%), Oxytetracycline (98.18%), Lincomycin (49.09%) | [83] |

| Kenya | 2018–2019 | DISC | Ampicillin (71.4%), Streptomycin (21%), Gentamycin (6%), Ciprofloxacin (3.2%), Norfloxacin (4.3%), Tetracycline (21%), Erythromycin (25.2%), Chloramphenicol (8.7%) | [84] | |

| Coliforms | Taiwan | 2020–2021 | DISC | Tetracycline (31.57%), Neomycin (21.05%), Bacitracin (68.42%), Ampicillin (31.57%), Oxacillin (100%), Cefuroxime (15.78%), Cephalothin (31.57%) | [29] |

| Escherichia coli | Finland | 2011 | MIC | Ampicillin (18.7%), Chloramphenicol (6.9%), Kanamycin (6.3%), Streptomycin (18.1%), Tetracycline (16.7%), Sulfamethoxazole (14.6%), Trimethoprim (10.4%) | [85] |

| Germany | 2017 | MIC | Ampicillin (12.1%), Ceftiofur (4.5%), Tetracycline (8.5%), Gentamicin (0.9%), Ciprofloxacin (2.2%) | [86] | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Denmark | 2016 | MIC | Ampicillin (83.3%), Streptomycin (5.6%) | [80] |

| China | 2019 | MIC | Amoxicillin (100%), Clavulanate (100%), Cefquinome (30.0%), Polymyxin B (30%), Tetracycline (30%), Kanamycin (30%), Ceftiofur (20%) | [87] | |

| Sweden | 2013 | MIC | Ampicillin (95.4%), Colistin (4.6%), Ciprofloxacin (4.6%), Tetracycline (9.1%) | [88] |

| Pathogens | Antimicrobials | Source | ARGs | Virulence Genes | Major Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Aminoglycosides and beta-lactams | Dairy farm waste | 14 beta-lactam resistance genes, including TEM-1, CTX-M-55, EC-15, CTX-M-14, and ampC; 5 multidrug resistance genes, including soxS, soxR, AcrAB-TolC-MarR, and marA | 40 different adherence-related virulence factors, including ecpA, elfA, eaeH, hcpA, fimA, fimG, and fimI | 48.4–100% isolates exhibited resistance to the tested antimicrobials | [96] |

| Escherichia coli | 18 antimicrobials, including ampicillin and carbenicillin | Water source in a dairy farm | blaTEM, blaCMY-2, blaSHY, aac(3)IIa, and aadA | NA | Resistance to ampicillin and carbenicillin was the most common Strong potential of E. coli to transfer ARGs to other pathogens | [100] |

| Staphylococcus spp. | Erythromycin, oxacillin, cephalothin, and gentamicin | Dairy farm environment | Bap, icaA, and mecA | NA | Mainly resistant to erythromycin (23%) and oxacillin (16%) | [101] |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 15 antimicrobials, including amoxicillin, ampicillin, and cefoxitin | Humans working with dairy animals | mecA | NA | Multidrug resistance was common | [102] |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 13 antimicrobials, including beta-lactams | Milker’s hands, liners, calves | mecA | sea, see, eno, can, ebps, fnbA, and coa | Most of the isolates were resistant to tested antimicrobials | [103] |

| Staphylococcus spp. | Beta-lactams, cephalosporins, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and gentamicin | Milking parlour, workers’ nasal cavities | blaZ, aacA-aphD, ermC, tetK, and mecA | NA | Prevalence of AMR Staphylococcus was high in milking parlour environmental samples | [98] |

| NA | Penicillins | Bovine feces | blaTEM | NA | Dairy farms could be considered a hotspot of antimicrobial ARGs | [97] |

| Alternatives | Major Findings | References |

|---|---|---|

| Leptospermum scoparium and Origanum vulgare | Antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcal and E. coli. | [110] |

| Oregano vulgare | Improves the physical condition of the udder and decreases SCC and WBC in cows affected with subclinical mastitis. Prevents the growth of S. aureus and E. coli. | [109] |

| Citrus × sinensis | Prevents S. aureus growth and biofilm formation, and reduces adhesion and invasion. | [115] |

| Minthostachys verticillate | Antibacterial capacity and anti-biofilm effect against E. coli, Bacillus pumilus, and Enterococcus faecium. | [116] |

| Thymus vulgaris, Oregano vulgare, Origanum majerana | Reduce the growth of Prototheca zopfii with resistance to fluconazole and flucytosine. | [117] |

| Alpinia purpurata | Bactericidal effects on S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and S. agalactiae. Curcumin and gingerol killed bacteria by disrupting their extracellular membrane. | [118] |

| Taraxacum officinale | Free radical scavenging, antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory activities. Downregulates the inflammatory response. | [119,120] |

| Nisin | Produced by Lactococcus lactis; showed antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria. | [121] |

| Polybia MP-1 | A 14-amino acid peptide from wasp venom with bactericidal activity against multidrug-resistant S. aureus, E. coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. | [122,123] |

| Lactoferrin | A multifunctional glycoprotein found in saliva, tears, bronchial mucus, colostrum, and milk, with antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, anticatabolic, and antioxidative effects. | [124,125] |

| Bacteriophages | Target and lyse mastitis-causing bacteria, such as S. aureus, E. coli, and S. uberis, by injecting their genetic material into bacterial cells, replicating inside the bacteria, and causing cell lysis. | [14,126] |

| Vaccination | Stimulates the immune system to recognize and respond to bacteria. Enhances adaptive immunity, promoting antibody production and immune memory. Boosts the neutrophil response, improving bacterial clearance and reducing inflammation. Toxoids in the vaccine neutralize bacterial toxins and adhesion inhibitors to prevent bacterial colonization. | [127,128] |

| Probiotics | Feeding probiotics to heifers and transition cows reduced the incidence of clinical mastitis, lowered SCC, and minimized days of discarded milk. Supplementation with Lactobacilli, yeast, and a lactic acid bacterium–maltodextrin mixture optimized the mammary microbiota and enhanced mammary resistance in dairy cows. | [129,130] |

| Stem cells | Intramammary administration of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AT-MSCs) eliminated S. aureus in the udder. MSCs exhibit immunomodulatory properties by secreting bioactive compounds and facilitating the repair of damaged tissues. | [131,132] |

| Nanotechnology-based therapy | A self-assembling tilmicosin nanogel had a higher cure rate against S. aureus-infected mastitis cows compared to conventional treatment methods. Cinnamon oil and silver nanoparticles exhibited bactericidal activity against S. agalactiae. | [133,134] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dhital, B.; Pudasaini, R.; Hsieh, J.-C.; Pudasaini, R.; Chen, Y.-T.; Chao, D.-Y.; Chiang, H.-I. One Health Perspective on Antimicrobial Resistance in Bovine Mastitis Pathogens—A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010084

Dhital B, Pudasaini R, Hsieh J-C, Pudasaini R, Chen Y-T, Chao D-Y, Chiang H-I. One Health Perspective on Antimicrobial Resistance in Bovine Mastitis Pathogens—A Narrative Review. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010084

Chicago/Turabian StyleDhital, Bigya, Rameshwor Pudasaini, Jui-Chun Hsieh, Ramchandra Pudasaini, Ying-Tsong Chen, Day-Yu Chao, and Hsin-I Chiang. 2026. "One Health Perspective on Antimicrobial Resistance in Bovine Mastitis Pathogens—A Narrative Review" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010084

APA StyleDhital, B., Pudasaini, R., Hsieh, J.-C., Pudasaini, R., Chen, Y.-T., Chao, D.-Y., & Chiang, H.-I. (2026). One Health Perspective on Antimicrobial Resistance in Bovine Mastitis Pathogens—A Narrative Review. Antibiotics, 15(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010084