Irrational and Inappropriate Use of Antifungals in the NICU: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology

1.2. Clinical Presentation

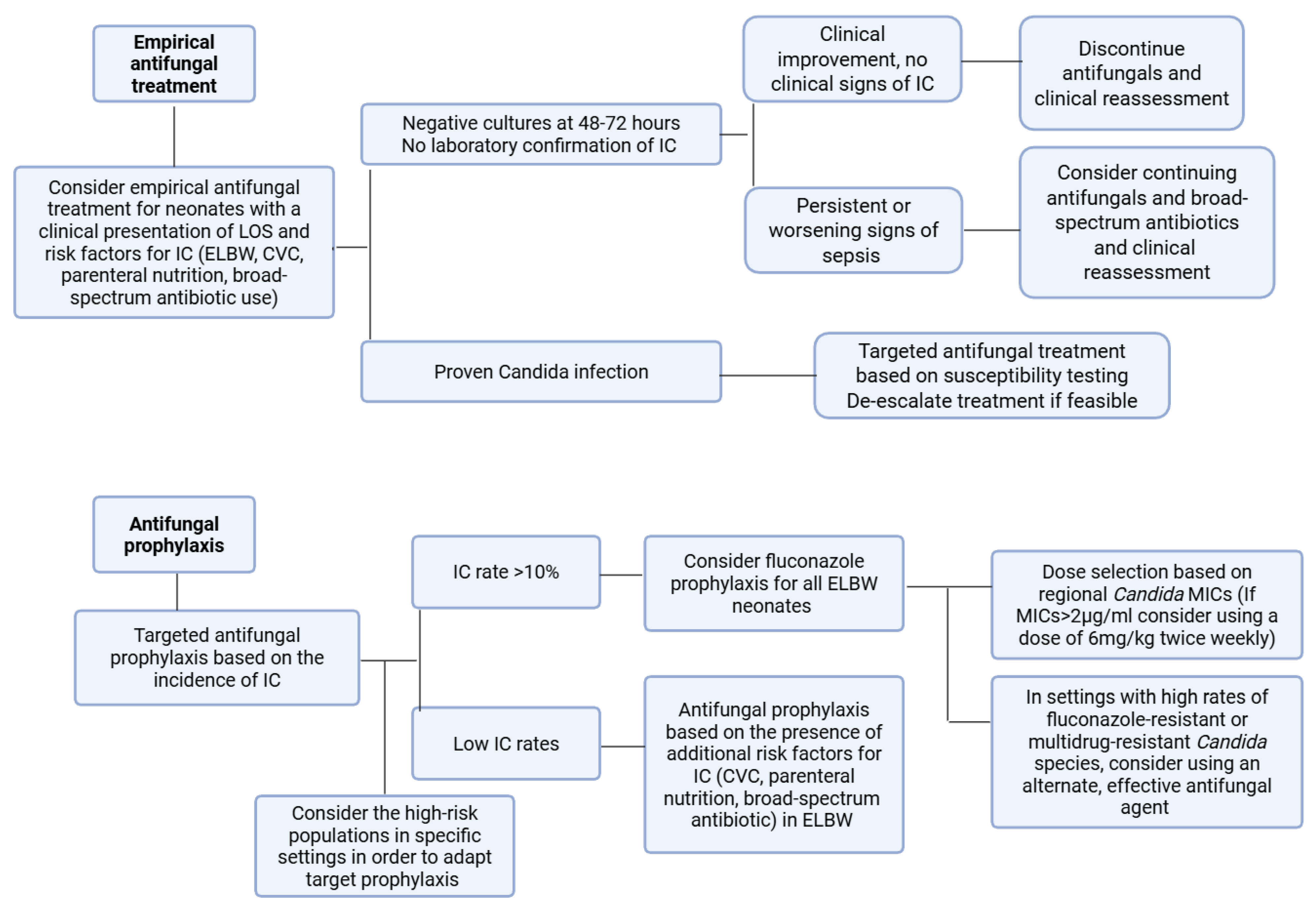

1.3. Antifungal Prophylaxis

1.4. Overview of Antifungals Used in Neonates

| Antifungal Class | Antifungal Agent | Mechanism of Action | Approved for Use in Neonates | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyenes [40,56] | Amphotericin B deoxycholate | Binding to ergosterol (component cytoplasmic membrane), leading to pore formation and increased permeability leading to cell death | Yes | Nephrotoxicity Electrolyte disturbances |

| Liposomal amphotericin B | Yes | Less adverse effects compared to Amphotericin B deoxycholate | ||

| Triazoles [39,40,57] | Fluconazole | Disruption of ergosterol biosynthesis, by inhibition of 14-a-sterol demethylase (cytochrome P-450 enzyme) | Yes | Hepatotoxicity Nephrotoxicity Gastrointestinal irritation QT prolongation Drug–drug interactions |

| Itraconazole | No | Hepatotoxicity Nephrotoxicity Cardiac effects Gastrointestinal irritation Drug–drug interactions | ||

| Voriconazole | No | Hepatotoxicity Visual disturbances Photosensitivity QT prolongation Drug–drug interactions | ||

| Echinocandins [58] | Micafungin | Disruption of synthesis of 1,3-beta-D-glucan (component of the fungal cell wall, essential for structural integrity) | Yes | Hepatotoxicity Gatsrointestinal irritation Hypokalemia |

| Caspofungin | No | Hepatotoxicity Gatsrointestinal irritation Hypokalemia | ||

| Anidulafungin | No | Hepatotoxicity Gatsrointestinal irritation Hypokalemia Potential accumulation of polysorbate 80 | ||

| Nucleoside analogue [52] | Flucytosine | Disruption of RNA and inhibition of DNA synthesis in the fungal cell | Yes | Hepatotoxicity Nephrotoxicity Bone marrow suppression Gastrointestinal irritation |

2. Methods

3. Factors Contributing to Inappropriate Use of Antifungals in Neonates

3.1. Challenges in Establishing a Definitive Diagnosis

3.2. Challenges with Antifungal Use in Neonates

3.3. Irrational and Inappropriate Use of Antifungal Prophylaxis

4. Consequences of Inappropriate Use of Antifungals

4.1. Microbiological Consequences

4.1.1. Emergence of Resistance

4.1.2. Antifungal Tolerance, Persistence, and Outbreaks in the NICU

4.2. Clinical Consequences

4.2.1. Antifungal Drug Toxicity

4.2.2. Drug Interactions

4.2.3. Effects on Mycobiome

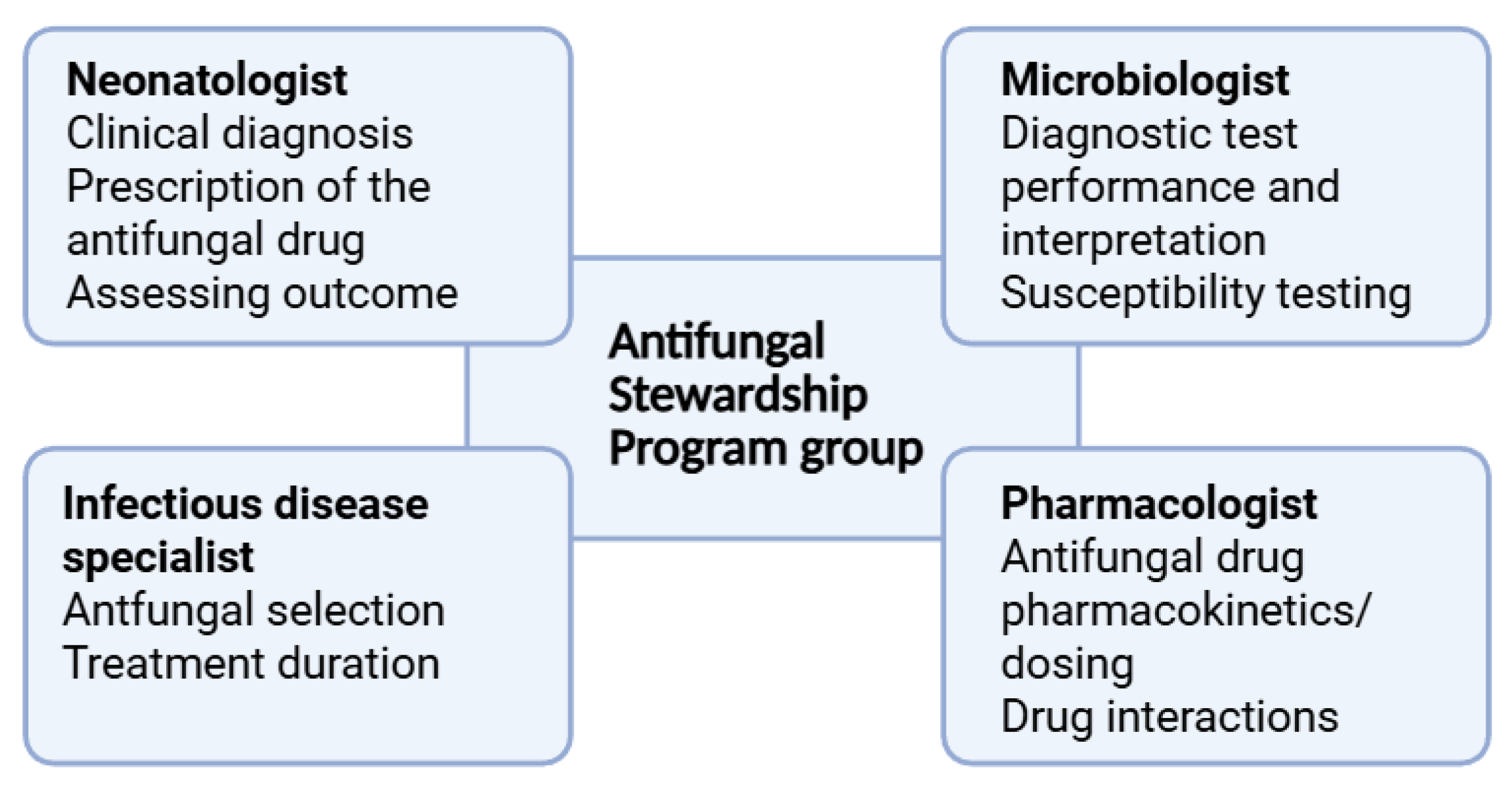

5. Antifungal Stewardship Programs in the NICU

5.1. Targets of AFS in the NICU

5.2. Implementation of AFS in the NICU

6. Future Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kariniotaki, C.; Thomou, C.; Gkentzi, D.; Panteris, E.; Dimitriou, G.; Hatzidaki, E. Neonatal Sepsis: A Comprehensive Review. Antibiotics 2024, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M.L.; Dickson, B.F.R.; Sharland, M.; Williams, P.C.M. Beyond Early- and Late-Onset Neonatal Sepsis Definitions: What Are the Current Causes of Neonatal Sepsis Globally? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Evidence. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 43, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, D.D.; Edwards, E.M.; Coggins, S.A.; Horbar, J.D.; Puopolo, K.M. Late-Onset Sepsis Among Very Preterm Infants. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022058813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, D.H.-T.; Wu, I.C.-Y.; Chang, L.-F.; Lu, M.J.-H.; Debnath, B.; Govender, N.P.; Sharland, M.; Warris, A.; Hsia, Y.; Ferreras-Antolin, L. The Burden of Neonatal Invasive Candidiasis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.S.; Benjamin, D.K.; Smith, P.B. The Epidemiology and Diagnosis of Invasive Candidiasis Among Premature Infants. Clin. Perinatol. 2015, 42, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, J.Y.; Roberts, A.; Synnes, A.; Canning, R.; Bodani, J.; Monterossa, L.; Shah, P.S. Invasive Fungal Infections in Neonates in Canada. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018, 37, 1154–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autmizguine, J.; Tan, S.; Cohen-Wolkowiez, M.; Cotten, C.M.; Wiederhold, N.; Goldberg, R.N.; Adams-Chapman, I.; Stoll, B.J.; Smith, P.B.; Benjamin, D.K. Antifungal Susceptibility and Clinical Outcome in Neonatal Candidiasis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018, 37, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.; O’Brien, K.; Robinson, J.L.; Davies, D.H.; Simpson, K.; Asztalos, E.; Langley, J.M.; Le Saux, N.; Sauve, R.; Synnes, A.; et al. Invasive Candidiasis in Low Birth Weight Preterm Infants: Risk Factors, Clinical Course and Outcome in a Prospective Multicenter Study of Cases and Their Matched Controls. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, D.K.; Stoll, B.J.; Fanaroff, A.A.; McDonald, S.A.; Oh, W.; Higgins, R.D.; Duara, S.; Poole, K.; Laptook, A.; Goldberg, R. Neonatal Candidiasis Among Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants: Risk Factors, Mortality Rates, and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 18 to 22 Months. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Kelly, E.; Luu, T.M.; Ye, X.Y.; Ting, J.; Shah, P.S.; Lee, S.K. Fungal Infection and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 18–30 Months in Preterm Infants. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1145252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.; Ferreras-Antolin, L.; Adhisivam, B.; Ballot, D.; Berkley, J.A.; Bernaschi, P.; Carvalheiro, C.G.; Chaikittisuk, N.; Chen, Y.; Chibabhai, V.; et al. Neonatal Invasive Candidiasis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Data from the NeoOBS Study. Med. Mycol. 2023, 61, myad010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jajoo, M.; Manchanda, V.; Chaurasia, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Gautam, H.; Agarwal, R.; Yadav, C.P.; Aggarwal, K.C.; Chellani, H.; Ramji, S.; et al. Alarming Rates of Antimicrobial Resistance and Fungal Sepsis in Outborn Neonates in North India. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0180705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warris, A.; Pana, Z.-D.; Oletto, A.; Lundin, R.; Castagnola, E.; Lehrnbecher, T.; Groll, A.H.; Roilides, E. Etiology and Outcome of Candidemia in Neonates and Children in Europe. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 39, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreras-Antolin, L.; Chowdhary, A.; Warris, A. Neonatal Invasive Candidiasis: Current Concepts. Indian. J. Pediatr. 2025, 92, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerihew, L.; Lamagni, T.L.; Brocklehurst, P.; McGuire, W. Invasive Fungal Infection in Very Low Birthweight Infants: National Prospective Surveillance Study. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006, 91, F188–F192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Sood, P.; Rudramurthy, S.M.; Chen, S.; Jillwin, J.; Iyer, R.; Sharma, A.; Harish, B.N.; Roy, I.; Kindo, A.J.; et al. Characteristics, Outcome and Risk Factors for Mortality of Paediatric Patients with ICU-acquired Candidemia in India: A Multicentre Prospective Study. Mycoses 2020, 63, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, K.; Roy, M.; Kabbani, S.; Anderson, E.J.; Farley, M.M.; Harb, S.; Harrison, L.H.; Bonner, L.; Wadu, V.L.; Marceaux, K.; et al. Neonatal and Pediatric Candidemia: Results From Population-Based Active Laboratory Surveillance in Four US Locations, 2009–2015. J. Pediatric. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2018, 7, e78–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezer, H.; Canpolat, F.E.; Dilmen, U. Invasive Fungal Infections during the Neonatal Period: Diagnosis, Treatment and Prophylaxis. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2012, 13, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, K.E.D.; Smith, P.B.; Puia-Dumitrescu, M.; Aleem, S. Invasive Fungal Infections in Neonates: A Review. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 91, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, R.; Scarrow, E.; Hornik, C.; Greenberg, R.G. Neonatal Invasive Candidiasis: Updates on Clinical Management and Prevention. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2022, 6, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, D.K.; Poole, C.; Steinbach, W.J.; Rowen, J.L.; Walsh, T.J. Neonatal Candidemia and End-Organ Damage: A Critical Appraisal of the Literature Using Meta-Analytic Techniques. Pediatrics 2003, 112, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.; Qiu, M.; Niu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Cao, J.; Tang, S.; Cheng, L.; Mei, Y.; Liang, H.; et al. End-Organ Damage from Neonatal Invasive Fungal Infection: A 14-Year Retrospective Study from a Tertiary Center in China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, I.; Spettel, K.; Willinger, B. Molecular Methods for the Diagnosis of Invasive Candidiasis. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Yang, Q. Updates in Laboratory Identification of Invasive Fungal Infection in Neonates. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paula Menezes, R.; da Silveira Ferreira, I.C.; Lopes, M.S.; de Jesus, T.A.; de Araujo, L.B.; dos Santos Pedroso, R.; de Brito Röder, D.V. Epidemiological Indicators and Predictors of Lethality Associated with Fungal Infections in a NICU: A Historical Series. J. Pediatr. 2024, 100, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermitzaki, N.; Baltogianni, M.; Tsekoura, E.; Giapros, V. Invasive Candida Infections in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Risk Factors and New Insights in Prevention. Pathogens 2024, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Ji, H.; Dong, X.; Li, J.; Li, H.; He, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; et al. Invasive Fungal Infection Is Associated with Antibiotic Exposure in Preterm Infants: A Multi-Centre Prospective Case–Control Study. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 134, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feja, K.N.; Wu, F.; Roberts, K.; Loughrey, M.; Nesin, M.; Larson, E.; Della-Latta, P.; Haas, J.; Cimiotti, J.; Saiman, L. Risk Factors for Candidemia in Critically Ill Infants: A Matched Case-Control Study. J. Pediatr. 2005, 147, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pera, A.; Byun, A.; Gribar, S.; Schwartz, R.; Kumar, D.; Parimi, P. Dexamethasone Therapy and Candida Sepsis in Neonates Less Than 1250 Grams. J. Perinatol. 2002, 22, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorafa, E.; Iosifidis, E.; Oletto, A.; Warris, A.; Castagnola, E.; Bruggemann, R.; Groll, A.H.; Lehrnbecher, T.; Ferreras Antolin, L.; Mesini, A.; et al. Antifungal Drug Usage in European Neonatal Units: A Multicenter Weekly Point Prevalence Study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 43, 1047–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, W.W.; Castagnola, E.; Groll, A.H.; Roilides, E.; Akova, M.; Arendrup, M.C.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Bassetti, M.; Bille, J.; Cornely, O.A.; et al. ESCMID Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candida Diseases 2012: Prevention and Management of Invasive Infections in Neonates and Children Caused by Candida spp. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.L.; Hornik, C.D.; Zimmerman, K. Pharmacokinetic, Efficacy, and Safety Considerations for the Use of Antifungal Drugs in the Neonatal Population. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2020, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, J. Review of Amphotericin B for Invasive Fungal Infections in Neonates and Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 2020, 2, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J.; Adler-Shohet, F.C.; Nguyen, C.; Lieberman, J.M. Nephrotoxicity Associated with Amphotericin B Deoxycholate in Neonates. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2009, 28, 1061–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, E.C.; Curtis, N.; Coghlan, B.; Cranswick, N.; Gwee, A. Adverse Effects of Amphotericin B in Children; a Retrospective Comparison of Conventional and Liposomal Formulations. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, K.J.; Fisher, B.T.; Zane, N.R. Administration and Dosing of Systemic Antifungal Agents in Pediatric Patients. Pediatr. Drugs 2020, 22, 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltogianni, M.; Giapros, V.; Dermitzaki, N. Recent Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment of Invasive Candidiasis in Neonates. Children 2024, 11, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, C.D.; Bondi, D.S.; Greene, N.M.; Cober, M.P.; John, B. Review of Fluconazole Treatment and Prophylaxis for Invasive Candidiasis in Neonates. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 26, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bersani, I.; Piersigilli, F.; Goffredo, B.M.; Santisi, A.; Cairoli, S.; Ronchetti, M.P.; Auriti, C. Antifungal Drugs for Invasive Candida Infections (ICI) in Neonates: Future Perspectives. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, E.J.; Choi, M.J.; Kim, M.-N.; Yong, D.; Lee, W.G.; Uh, Y.; Kim, T.S.; Byeon, S.A.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S.H.; et al. Fluconazole-Resistant Candida Glabrata Bloodstream Isolates, South Korea, 2008–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroczyńska, M.; Brillowska-Dąbrowska, A. Review on Current Status of Echinocandins Use. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.-A.; Slavin, M.A.; Sorrell, T.C. Echinocandin Antifungal Drugs in Fungal Infections. Drugs 2011, 71, 11–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, P.S.; Patwardhan, S.A.; Joshi, R.S.; Dhupad, S.; Rane, T.; Prayag, A.P. Comparative Efficacies of the Three Echinocandins for Candida Auris Candidemia: Real World Evidence from a Tertiary Centre in India. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Nakwa, F.L.; Araujo Motta, F.; Liu, H.; Dorr, M.B.; Anderson, L.J.; Kartsonis, N. A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial Investigating the Efficacy of Caspofungin versus Amphotericin B Deoxycholate in the Treatment of Invasive Candidiasis in Neonates and Infants Younger than 3 Months of Age. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, P.; Wu, C.; Tweddle, L.; Roilides, E. Micafungin in Premature and Non-Premature Infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2014, 33, e291–e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, C.; Carver, P. Update on Echinocandin Antifungals. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 29, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekoura, M.; Ioannidou, M.; Pana, Z.-D.; Haidich, A.-B.; Antachopoulos, C.; Iosifidis, E.; Kolios, G.; Roilides, E. Efficacy and Safety of Echinocandins for the Treatment of Invasive Candidiasis in Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/mycamine-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/021506s023lbl.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Agudelo-Pérez, S.; Fernández-Sarmiento, J.; Rivera León, D.; Peláez, R.G. Metagenomics by Next-Generation Sequencing (MNGS) in the Etiological Characterization of Neonatal and Pediatric Sepsis: A Systematic Review. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1011723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigera, L.S.M.; Denning, D.W. Flucytosine and Its Clinical Usage. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, 20499361231161387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreras-Antolín, L.; Irwin, A.; Atra, A.; Dermirjian, A.; Drysdale, S.B.; Emonts, M.; McMaster, P.; Paulus, S.; Patel, S.; Kinsey, S.; et al. Neonatal Antifungal Consumption Is Dominated by Prophylactic Use; Outcomes From The Pediatric Antifungal Stewardship: Optimizing Antifungal Prescription Study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortmann, I.; Hartz, A.; Paul, P.; Pulzer, F.; Müller, A.; Böttger, R.; Proquitté, H.; Dawczynski, K.; Simon, A.; Rupp, J.; et al. Antifungal Treatment and Outcome in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018, 37, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourti, M.; Chorafa, E.; Roilides, E.; Iosifidis, E. Antifungal Stewardship Programs in Children: Challenges and Opportunities. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, e246–e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koren, G.; Lau, A.; Klein, J.; Golas, C.; Bologa-Campeanu, M.; Soldin, S.; MacLeod, S.M.; Prober, C. Pharmacokinetics and Adverse Effects of Amphotericin B in Infants and Children. J. Pediatr. 1988, 113, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.B.; Kauffman, C.A. Voriconazole: A New Triazole Antifungal Agent. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dermitzaki, N.; Balomenou, F.; Gialamprinou, D.; Giapros, V.; Rallis, D.; Baltogianni, M. Perspectives on the Use of Echinocandins in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keighley, C.; Cooley, L.; Morris, A.J.; Ritchie, D.; Clark, J.E.; Boan, P.; Worth, L.J. Consensus Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Invasive Candidiasis in Haematology, Oncology and Intensive Care Settings, 2021. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, D.P.; Friedman, D.F.; Chiotos, K.; Sullivan, K.V. Blood Volume Required for Detection of Low Levels and Ultralow Levels of Organisms Responsible for Neonatal Bacteremia by Use of Bactec Peds Plus/F, Plus Aerobic/F Medium, and the BD Bactec FX System: An In Vitro Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 3609–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelonka, R.L.; Moser, S.A. Time to Positive Culture Results in Neonatal Candida Septicemia. J. Pediatr. 2003, 142, 564–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliquennois, P.; Scherdel, P.; Lavergne, R.; Flamant, C.; Morio, F.; Cohen, J.F.; Launay, E.; Gras Le Guen, C. Serum (1 → 3)-β-D-glucan Could Be Useful to Rule out Invasive Candidiasis in Neonates with an Adapted Cut-off. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.F.; Ouziel, A.; Matczak, S.; Brice, J.; Spijker, R.; Lortholary, O.; Bougnoux, M.-E.; Toubiana, J. Diagnostic Accuracy of Serum (1,3)-Beta-d-Glucan for Neonatal Invasive Candidiasis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagna, M.T.; Lovero, G.; De Giglio, O.; Iatta, R.; Caggiano, G.; Montagna, O.; Laforgia, N.; AURORA Project Group. Invasive Fungal Infections in Neonatal Intensive Care Units of Southern Italy: A Multicentre Regional Active Surveillance (AURORA Project). J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2010, 51, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri, S.; Trovato, L.; Betta, P.; Romeo, M.G.; Nicoletti, G. Experience with the Platelia Candida ELISA for the Diagnosis of Invasive Candidosis in Neonatal Patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppler, A.R.; Fisher, B.T.; Lehrnbecher, T.; Walsh, T.J.; Steinbach, W.J. Role of Molecular Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Invasive Fungal Diseases in Children. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2017, 6, S32–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga, S.; Clark, R.H.; Laughon, M.; Walsh, T.J.; Hope, W.W.; Benjamin, D.K.; Kaufman, D.; Arrieta, A.; Benjamin, D.K.; Smith, P.B. Changes in the Incidence of Candidiasis in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreras-Antolín, L.; Irwin, A.; Atra, A.; Chapelle, F.; Drysdale, S.B.; Emonts, M.; McMaster, P.; Paulus, S.; Patel, S.; Rompola, M.; et al. Pediatric Antifungal Prescribing Patterns Identify Significant Opportunities to Rationalize Antifungal Use in Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2022, 41, e69–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreras-Antolin, L.; Bielicki, J.; Warris, A.; Sharland, M.; Hsia, Y. Global Divergence of Antifungal Prescribing Patterns. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreras-Antolín, L.; Sharland, M.; Warris, A. Management of Invasive Fungal Disease in Neonates and Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, S2–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rose, D.U.; Ronchetti, M.P.; Santisi, A.; Bernaschi, P.; Martini, L.; Porzio, O.; Dotta, A.; Auriti, C. Stop in Time: How to Reduce Unnecessary Antibiotics in Newborns with Late-Onset Sepsis in Neonatal Intensive Care. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astorga, M.C.; Piscitello, K.J.; Menda, N.; Ebert, A.M.; Ebert, S.C.; Porte, M.A.; Kling, P.J. Antibiotic Stewardship in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Effects of an Automatic 48-Hour Antibiotic Stop Order on Antibiotic Use. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2019, 8, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermitzaki, N.; Atzemoglou, N.; Giapros, V.; Baltogianni, M.; Rallis, D.; Gouvias, T.; Serbis, A.; Drougia, A. Elimination of Candida Sepsis and Reducing Several Morbidities in a Tertiary NICU in Greece After Changing Antibiotic, Ventilation, and Nutrition Protocols. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestner, J.M.; Smith, P.B.; Cohen-Wolkowiez, M.; Benjamin, D.K.; Hope, W.W. Antifungal Agents and Therapy for Infants and Children with Invasive Fungal Infections: A Pharmacological Perspective. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestner, J.M.; Versporten, A.; Doerholt, K.; Warris, A.; Roilides, E.; Sharland, M.; Bielicki, J.; Goossens, H. Systemic Antifungal Prescribing in Neonates and Children: Outcomes from the Antibiotic Resistance and Prescribing in European Children (ARPEC) Study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, S.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E.; Elie, V.; Legrand, F.; Barin-Le Guellec, C.; Aurich, B.; Biran, V.; Dusang, B.; Goudjil, S.; Coopman, S.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Fluconazole and Micafungin in Neonates with Systemic Candidiasis: A Randomized, Open-label Clinical Trial. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1989–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O.A.; Sprute, R.; Bassetti, M.; Chen, S.C.-A.; Groll, A.H.; Kurzai, O.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Revathi, G.; et al. Global Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candidiasis: An Initiative of the ECMM in Cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e280–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rose, D.; Bersani, I.; Ronchetti, M.; Piersigilli, F.; Cairoli, S.; Dotta, A.; Desai, A.; Kovanda, L.; Goffredo, B.; Auriti, C. Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Concentrations of Micafungin Administered at High Doses in Critically Ill Infants with Systemic Candidiasis: A Pooled Analysis of Two Studies. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.B.; Walsh, T.J.; Hope, W.; Arrieta, A.; Takada, A.; Kovanda, L.L.; Kearns, G.L.; Kaufman, D.; Sawamoto, T.; Buell, D.N.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of an Elevated Dosage of Micafungin in Premature Neonates. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2009, 28, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemian, S.M.; Farhadi, T.; Velayati, A.A. Caspofungin: A Review of Its Characteristics, Activity, and Use in Intensive Care Units. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosifidis, E.; Papachristou, S.; Roilides, E. Advances in the Treatment of Mycoses in Pediatric Patients. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrando, G.; Castagnola, E. Prophylaxis of Invasive Fungal Infection in Neonates: A Narrative Review for Practical Purposes. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robati Anaraki, M.; Nouri-Vaskeh, M.; Abdoli Oskoei, S. Fluconazole Prophylaxis against Invasive Candidiasis in Very Low and Extremely Low Birth Weight Preterm Neonates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2021, 64, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, J.E.; Kaufman, D.A.; Kicklighter, S.D.; Bhatia, J.; Testoni, D.; Gao, J.; Smith, P.B.; Prather, K.O.; Benjamin, D.K. Fluconazole Prophylaxis for the Prevention of Candidiasis in Premature Infants: A Meta-Analysis Using Patient-Level Data. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Xie, D.; He, N.; Wang, X.; Dong, W.; Lei, X. Prophylactic Use of Fluconazole in Very Premature Infants. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 726769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Rajapakse, N.; Sauer, H.E.; Ellsworth, K.; Dinnes, L.; Madigan, T. A Quality Improvement Project Aimed at Standardizing the Prescribing of Fluconazole Prophylaxis in a Level IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Pediatr. Qual. Saf. 2022, 7, e579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitkamp, J.-H.; Ozdas, A.; LaFleur, B.; Potts, A.L. Fluconazole Prophylaxis for Prevention of Invasive Fungal Infections in Targeted Highest Risk Preterm Infants Limits Drug Exposure. J. Perinatol. 2008, 28, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonart, L.P.; Tonin, F.S.; Ferreira, V.L.; Tavares da Silva Penteado, S.; de Araújo Motta, F.; Pontarolo, R. Fluconazole Doses Used for Prophylaxis of Invasive Fungal Infection in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: A Network Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2017, 185, 129–135.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momper, J.D.; Capparelli, E.V.; Wade, K.C.; Kantak, A.; Dhanireddy, R.; Cummings, J.J.; Nedrelow, J.H.; Hudak, M.L.; Mundakel, G.T.; Natarajan, G.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Fluconazole in Premature Infants with Birth Weights Less than 750 Grams. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5539–5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, K.C.; Benjamin, D.K.; Kaufman, D.A.; Ward, R.M.; Smith, P.B.; Jayaraman, B.; Adamson, P.C.; Gastonguay, M.R.; Barrett, J.S. Fluconazole Dosing for the Prevention or Treatment of Invasive Candidiasis in Young Infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2009, 28, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, B.; Ding, Y.; Xu, S.; Qin, P.; Fu, J. Epidemiology of and Risk Factors for Neonatal Candidemia at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Western China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaguelidou, F.; Pandolfini, C.; Manzoni, P.; Choonara, I.; Bonati, M.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E. European Survey on the Use of Prophylactic Fluconazole in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2012, 171, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Matary, A.; Almahmoud, L.; Masmoum, R.; Alenezi, S.; Aldhafiri, S.; Almutairi, A.; Alatram, H.; Alenzi, A.; Alajm, M.; Artam Alajmi, A.; et al. Oral Nystatin Prophylaxis for the Prevention of Fungal Colonization in Very Low Birth Weight Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cureus 2022, 14, e28345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, N.; Cleminson, J.; Darlow, B.A.; McGuire, W. Prophylactic Oral/Topical Non-Absorbed Antifungal Agents to Prevent Invasive Fungal Infection in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD003478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandramati, J.; Sadanandan, L.; Kumar, A.; Ponthenkandath, S. Neonatal Candida Auris Infection: Management and Prevention Strategies—A Single Centre Experience. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2020, 56, 1565–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanafani, Z.A.; Perfect, J.R. Resistance to Antifungal Agents: Mechanisms and Clinical Impact. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, C.M.; Ryan, L.K.; Gera, M.; Choudhuri, S.; Lyle, N.; Ali, K.A.; Diamond, G. Antifungals and Drug Resistance. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1722–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Berman, J.; Bicanic, T.; Bignell, E.M.; Bowyer, P.; Bromley, M.; Brüggemann, R.; Garber, G.; Cornely, O.A.; et al. Tackling the Emerging Threat of Antifungal Resistance to Human Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, A.; Ferrara, F.; Boccellino, M.; Ponzo, A.; Cimmino, C.; Comberiati, E.; Zovi, A.; Clemente, S.; Sabbatucci, M. Antifungal Drug Resistance: An Emergent Health Threat. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, C.M.; de Carvalho, A.M.R.; Macêdo, D.P.C.; Jucá, M.B.; Amorim, R.d.J.M.; Neves, R.P. Candidemia in Brazilian Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Risk Factors, Epidemiology, and Antifungal Resistance. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noni, M.; Stathi, A.; Vaki, I.; Velegraki, A.; Zachariadou, L.; Michos, A. Changing Epidemiology of Invasive Candidiasis in Children during a 10-Year Period. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykac, K.; Anac, E.G.; Seyrek, B.E.; Karaman, A.; Demir, O.O.; Unalan-Altintop, T.; Gulmez, D.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Avci, H.; Cengiz, A.B.; et al. Trends in Pediatric Invasive Candidiasis: Shifting Species Distribution and Improving Outcomes. Mycopathologia 2025, 190, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autmizguine, J.; Smith, P.B.; Prather, K.; Bendel, C.; Natarajan, G.; Bidegain, M.; Kaufman, D.A.; Burchfield, D.J.; Ross, A.S.; Pandit, P.; et al. Effect of Fluconazole Prophylaxis on Candida Fluconazole Susceptibility in Premature Infants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 3482–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luparia, M.; Landi, F.; Mesini, A.; Militello, M.A.; Galletto, P.; Farina, D.; Castagnola, E.; Manzoni, P. Fungal Ecology in a Tertiary Neonatal Intensive Care Unit after 16 Years of Routine Fluconazole Prophylaxis: No Emergence of Native Fluconazole-Resistant Strains. Am. J. Perinatol. 2019, 36, S126–S133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andes, D.; Forrest, A.; Lepak, A.; Nett, J.; Marchillo, K.; Lincoln, L. Impact of Antimicrobial Dosing Regimen on Evolution of Drug Resistance In Vivo: Fluconazole and Candida Albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2374–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, P.; Arisio, R.; Mostert, M.; Leonessa, M.; Farina, D.; Latino, M.A.; Gomirato, G. Prophylactic Fluconazole Is Effective in Preventing Fungal Colonization and Fungal Systemic Infections in Preterm Neonates: A Single-Center, 6-Year, Retrospective Cohort Study. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e22–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, D.; Boyle, R.; Hazen, K.C.; Patrie, J.T.; Robinson, M.; Donowitz, L.G. Fluconazole Prophylaxis against Fungal Colonization and Infection in Preterm Infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 34, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, C.M.; Campbell, J.R.; Zaccaria, E.; Baker, C.J. Fluconazole Prophylaxis in Extremely Low Birth Weight Neonates Reduces Invasive Candidiasis Mortality Rates Without Emergence of Fluconazole-Resistant Candida Species. Pediatrics 2008, 121, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvikivi, E.; Lyytikäinen, O.; Soll, D.R.; Pujol, C.; Pfaller, M.A.; Richardson, M.; Koukila-Kähkölä, P.; Luukkainen, P.; Saxén, H. Emergence of Fluconazole Resistance in a Candida Parapsilosis Strain That Caused Infections in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 2729–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.-S.; Shin, S.H.; Choi, C.W.; Kim, E.-K.; Choi, E.H.; Kim, B.I.; Choi, J.-H. Efficacy and Safety of Fluconazole Prophylaxis in Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants: Multicenter Pre-Post Cohort Study. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokou, R.; Palioura, A.E.; Kopanou Taliaka, P.; Konstantinidi, A.; Tsantes, A.G.; Piovani, D.; Tsante, K.A.; Gounari, E.A.; Iliodromiti, Z.; Boutsikou, T.; et al. Candida Auris Infection, a Rapidly Emerging Threat in the Neonatal Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse, M.B.; Gulati, M.; Johnson, A.D.; Nobile, C.J. Development and Regulation of Single- and Multi-Species Candida Albicans Biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, V.; Kissmann, A.-K.; Firacative, C.; Rosenau, F. Biofilm-Associated Candidiasis: Pathogenesis, Prevalence, Challenges and Therapeutic Options. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalheiro, M.; Teixeira, M.C. Candida Biofilms: Threats, Challenges, and Promising Strategies. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Chandra, J.; Kuhn, D.M.; Ghannoum, M.A. Mechanism of Fluconazole Resistance in Candida Albicans Biofilms: Phase-Specific Role of Efflux Pumps and Membrane Sterols. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 4333–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFleur, M.D.; Kumamoto, C.A.; Lewis, K. Candida Albicans Biofilms Produce Antifungal-Tolerant Persister Cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 3839–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.A.; Eilertson, B.; Cadnum, J.L.; Whitlow, C.S.; Jencson, A.L.; Safdar, N.; Krein, S.L.; Tanner, W.D.; Mayer, J.; Samore, M.H.; et al. Environmental Contamination with Candida Species in Multiple Hospitals Including a Tertiary Care Hospital with a Candida Auris Outbreak. Pathog. Immun. 2019, 4, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dire, O.; Ahmad, A.; Duze, S.; Patel, M. Survival of Candida Auris on Environmental Surface Materials and Low-Level Resistance to Disinfectant. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 137, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Menezes, R.; de Oliveira Melo, S.G.; Bessa, M.A.S.; Silva, F.F.; Alves, P.G.V.; Araújo, L.B.; Penatti, M.P.A.; Abdallah, V.O.S.; von Dollinger de Brito Röder, D.; dos Santos Pedroso, R. Candidemia by Candida Parapsilosis in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Human and Environmental Reservoirs, Virulence Factors, and Antifungal Susceptibility. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2020, 51, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldejohann, A.M.; Wiese-Posselt, M.; Gastmeier, P.; Kurzai, O. Expert Recommendations for Prevention and Management of Candida Auris Transmission. Mycoses 2022, 65, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, A.; Gotoh, K.; Iwahashi, J.; Togo, A.; Horita, R.; Miura, M.; Kinoshita, M.; Ohta, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Watanabe, H. Characteristics of Biofilms Formed by C. Parapsilosis Causing an Outbreak in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekana, D.; Naicker, S.D.; Shuping, L.; Velaphi, S.; Nakwa, F.L.; Wadula, J.; Govender, N.P. Candida Auris Clinical Isolates Associated with Outbreak in Neonatal Unit of Tertiary Academic Hospital, South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado-Socarras, J.L.; Vargas-Soler, J.A.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Villegas-Lamus, K.C.; Rojas-Torres, J.P.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. A Cluster of Neonatal Infections Caused by Candida Auris at a Large Referral Center in Colombia. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2021, 10, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, H.; Kanamori, H.; Nakayama, A.; Sato, T.; Katsumi, M.; Chida, T.; Ikeda, S.; Seki, R.; Arai, T.; Kamei, K.; et al. A Cluster of Candida Parapsilosis Displaying Fluconazole-Trailing in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Successfully Contained by Multiple Infection-Control Interventions. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2024, 4, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baley, J.E.; Meyers, C.; Kliegman, R.M.; Jacobs, M.R.; Blumer, J.L. Pharmacokinetics, Outcome of Treatment, and Toxic Effects of Amphotericin B and 5-Fluorocytosine in Neonates. J. Pediatr. 1990, 116, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egunsola, O.; Adefurin, A.; Fakis, A.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E.; Choonara, I.; Sammons, H. Safety of Fluconazole in Paediatrics: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 69, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doby, E.H.; Benjamin, D.K.; Blaschke, A.J.; Ward, R.M.; Pavia, A.T.; Martin, P.L.; Driscoll, T.A.; Cohen-Wolkowiez, M.; Moran, C. Therapeutic Monitoring of Voriconazole in Children Less Than Three Years of Age. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2012, 31, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roilides, E.; Carlesse, F.; Tawadrous, M.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Conte, U.; Raber, S.; Swanson, R.; Yan, J.L.; Aram, J.A.; Queiroz-Telles, F. Safety, Efficacy and Pharmacokinetics of Anidulafungin in Patients 1 Month to <2 Years of Age With Invasive Candidiasis, Including Candidemia. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 39, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrek, L. A Synopsis of Current Theories on Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity. Life 2023, 13, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Cai, X.; Ye, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, F.; Zheng, C. The Role of Microbiota in Infant Health: From Early Life to Adulthood. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 708472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Aschenbrenner, D.; Yoo, J.Y.; Zuo, T. The Gut Mycobiome in Health, Disease, and Clinical Applications in Association with the Gut Bacterial Microbiome Assembly. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e969–e983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, D.; Salamon, S.; Wróblewska-Seniuk, K. It’s Time to Shed Some Light on the Importance of Fungi in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: What Do We Know about the Neonatal Mycobiome? Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1355418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Fan, N.; Ma, S.; Cheng, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, G. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Pathogenesis, Diseases, Prevention, and Therapy. MedComm 2025, 6, e70168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.A.; Phillips, S.; Telatin, A.; Baker, D.; Ansorge, R.; Clarke, P.; Hall, L.J.; Carding, S.R. Preterm Infants Harbour a Rapidly Changing Mycobiota That Includes Candida Pathobionts. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpakosi, A.; Sokou, R.; Theodoraki, M.; Kaliouli-Antonopoulou, C. Neonatal Gut Mycobiome: Immunity, Diversity of Fungal Strains, and Individual and Non-Individual Factors. Life 2024, 14, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, M.L.; Limon, J.J.; Bar, A.S.; Leal, C.A.; Gargus, M.; Tang, J.; Brown, J.; Funari, V.A.; Wang, H.L.; Crother, T.R.; et al. Immunological Consequences of Intestinal Fungal Dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutin, R.C.T.; Sbihi, H.; McLaughlin, R.J.; Hahn, A.S.; Konwar, K.M.; Loo, R.S.; Dai, D.; Petersen, C.; Brinkman, F.S.L.; Winsor, G.L.; et al. Composition and Associations of the Infant Gut Fungal Microbiota with Environmental Factors and Childhood Allergic Outcomes. mBio 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, W.; He, F.; Li, J. The Mycobiome as Integral Part of the Gut Microbiome: Crucial Role of Symbiotic Fungi in Health and Disease. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2440111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.V.; Leonardi, I.; Iliev, I.D. Gut Mycobiota in Immunity and Inflammatory Disease. Immunity 2019, 50, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, K.A.; Gurung, M.; Talatala, R.; Rearick, J.R.; Ruebel, M.L.; Stephens, K.E.; Yeruva, L. The Role of Early Life Gut Mycobiome on Child Health. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiemsma, L.T.; Turvey, S.E. Asthma and the Microbiome: Defining the Critical Window in Early Life. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2017, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, K.E.; Sitarik, A.R.; Havstad, S.; Lin, D.L.; Levan, S.; Fadrosh, D.; Panzer, A.R.; LaMere, B.; Rackaityte, E.; Lukacs, N.W.; et al. Neonatal Gut Microbiota Associates with Childhood Multisensitized Atopy and T Cell Differentiation. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.-C.; Arévalo, A.; Stiemsma, L.; Dimitriu, P.; Chico, M.E.; Loor, S.; Vaca, M.; Boutin, R.C.T.; Morien, E.; Jin, M.; et al. Associations between Infant Fungal and Bacterial Dysbiosis and Childhood Atopic Wheeze in a Nonindustrialized Setting. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 424–434.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schei, K.; Simpson, M.R.; Avershina, E.; Rudi, K.; Øien, T.; Júlíusson, P.B.; Underhill, D.; Salamati, S.; Ødegård, R.A. Early Gut Fungal and Bacterial Microbiota and Childhood Growth. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 572538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.W.; Mercer, E.M.; Moossavi, S.; Laforest-Lapointe, I.; Reyna, M.E.; Becker, A.B.; Simons, E.; Mandhane, P.J.; Turvey, S.E.; Moraes, T.J.; et al. Maturational Patterns of the Infant Gut Mycobiome Are Associated with Early-Life Body Mass Index. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 100928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgo, F.; Verduci, E.; Riva, A.; Lassandro, C.; Riva, E.; Morace, G.; Borghi, E. Relative Abundance in Bacterial and Fungal Gut Microbes in Obese Children: A Case Control Study. Child. Obes. 2017, 13, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Serradell, L.; Liu-Tindall, J.; Planells-Romeo, V.; Aragón-Serrano, L.; Isamat, M.; Gabaldón, T.; Lozano, F.; Velasco-de Andrés, M. The Human Mycobiome: Composition, Immune Interactions, and Impact on Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Guo, Z.; Wang, J.; Gao, D.; Xu, Q.; Hua, S. Gut Mycobiome in Cardiometabolic Disease Progression: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1659654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiew, P.Y.; Mac Aogain, M.; Ali, N.A.B.M.; Thng, K.X.; Goh, K.; Lau, K.J.X.; Chotirmall, S.H. The Mycobiome in Health and Disease: Emerging Concepts, Methodologies and Challenges. Mycopathologia 2020, 185, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Hettle, D.; Hutchings, S.; Wade, S.; Forrest-Jones, K.; Sequeiros, I.; Borman, A.; Johnson, E.M.; Harding, I. Promoting Antifungal Stewardship through an Antifungal Multidisciplinary Team in a Paediatric and Adult Tertiary Centre in the UK. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 6, dlae119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capoor, M.R.; Subudhi, C.P.; Collier, A.; Bal, A.M. Antifungal Stewardship with an Emphasis on Candidaemia. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 19, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markogiannakis, A.; Korantanis, K.; Gamaletsou, M.N.; Samarkos, M.; Psichogiou, M.; Daikos, G.; Sipsas, N.V. Impact of a Non-Compulsory Antifungal Stewardship Program on Overuse and Misuse of Antifungal Agents in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 57, 106255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahar, F.; Alhamad, H.; Abu Assab, M.; Abu-Farha, R.; Alawi, L.; Khaleel, S. The Impact of Antifungal Stewardship on Clinical and Performance Measures: A Global Systematic Review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, K.; Moreno, M.T.; Espinosa, M.; Sáez-Llorens, X. Impact of routine fluconazole prophylaxis for premature infants with birth weights of less than 1250 grams in a developing country. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2010, 29, 1050–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uko, S.; Soghier, L.M.; Vega, M.; Marsh, J.; Reinersman, G.T.; Herring, L.; Dave, V.A.; Nafday, S.; Brion, L.P. Targeted Short-Term Fluconazole Prophylaxis Among Very Low Birth Weight and Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, D.A. “Getting to Zero”: Preventing Invasive Candida Infections and Eliminating Infection-Related Mortality and Morbidity in Extremely Preterm Infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2012, 88, S45–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.D.; Lewis, R.E.; Dodds Ashley, E.S.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Zaoutis, T.; Thompson, G.R.; Andes, D.R.; Walsh, T.J.; Pappas, P.G.; Cornely, O.A.; et al. Core Recommendations for Antifungal Stewardship: A Statement of the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, S175–S198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Barnes, R.; Brüggemann, R.J.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Warris, A. The Role of the Multidisciplinary Team in Antifungal Stewardship. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, ii37–ii42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Palomar, N.; Garcia-Palop, B.; Melendo, S.; Martín, M.T.; Renedo-Miró, B.; Soler-Palacin, P.; Fernández-Polo, A. Antifungal Stewardship in a Tertiary Care Paediatric Hospital: The PROAFUNGI Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ESCMID 2012 |

Fluconazole prophylaxis 3–6 mg/kg iv or per os biweekly.

|

| Lactoferrin 100 mg/day alone or in combination with Lactobacillus 106 colony-forming units once daily (moderate recommendation; moderate-quality evidence) |

| Nystatin 100,000 U per os every 8 h (moderate recommendation; moderate-quality evidence) |

| IDSA 2016 |

| Fluconazole prophylaxis 3–6 mg/kg iv or per os biweekly for six weeks for all ELBW neonates in NICUs with a high incidence of IC (>10%) (strong recommendation; high-quality evidence) |

| Lactoferrin 100 mg/day per os (weak recommendation; moderate-quality evidence) |

| Nystatin 100,000 U per os every 8 h for six weeks, in cases where fluconazole cannot be used due to unavailability or resistance (weak recommendation; moderate-quality evidence) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dermitzaki, N.; Balomenou, F.; Kosmeri, C.; Baltogianni, M.; Nikolaou, A.; Serbis, A.; Giapros, V. Irrational and Inappropriate Use of Antifungals in the NICU: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010073

Dermitzaki N, Balomenou F, Kosmeri C, Baltogianni M, Nikolaou A, Serbis A, Giapros V. Irrational and Inappropriate Use of Antifungals in the NICU: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleDermitzaki, Niki, Foteini Balomenou, Chrysoula Kosmeri, Maria Baltogianni, Aikaterini Nikolaou, Anastasios Serbis, and Vasileios Giapros. 2026. "Irrational and Inappropriate Use of Antifungals in the NICU: A Narrative Review" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010073

APA StyleDermitzaki, N., Balomenou, F., Kosmeri, C., Baltogianni, M., Nikolaou, A., Serbis, A., & Giapros, V. (2026). Irrational and Inappropriate Use of Antifungals in the NICU: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics, 15(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010073