Development of DEEP-URO, a Generic Research Tool for Enhancing Antimicrobial Stewardship in a Surgical Specialty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Organizational Items

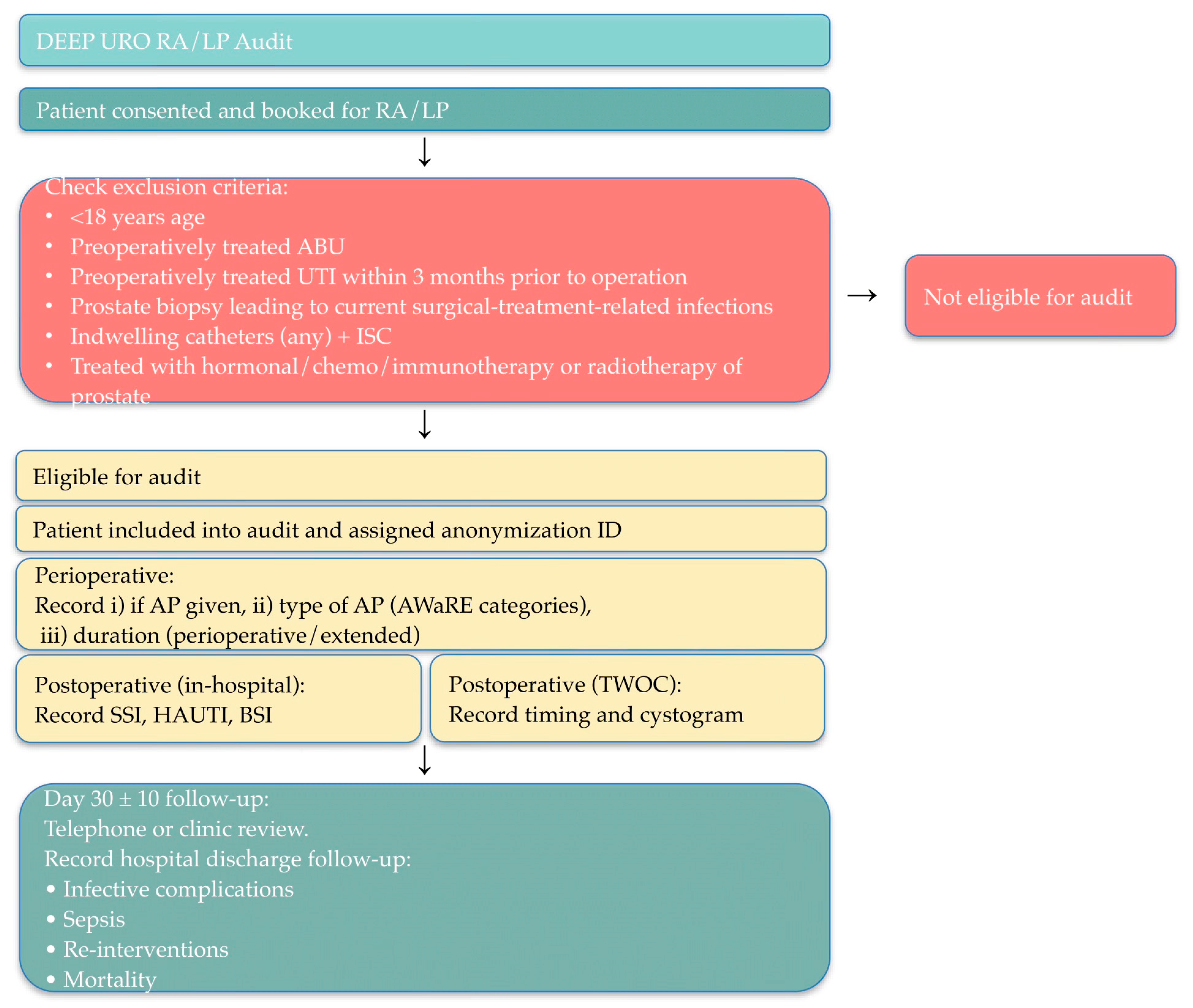

2.1.1. Study Design

2.1.2. Study Setting

2.1.3. Site Eligibility Criteria

- Provide routine follow-up for the patients undergoing the procedure being studied at or around day 30 post-surgery.

- Ability to access and extract data from operative notes (for AP variation documentation) and standard follow-up documentation (clinic letters, discharge summaries, readmission notes).

- Obtain local audit registration/governance approval.

- Demonstrate ability to maintain data completeness and quality standards (≥95%).

- Ability to confirm infection outcomes through local records or coordinated communication with downstream care providers.

- Centers with care pathways that discharge patients without structured postoperative follow-up (e.g., no day 30 contact) shall be excluded.

2.1.4. Patient Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Outcomes

2.2.1. Outcome Measures and Audit Benchmark Values

2.2.2. Case Definitions

2.2.3. Antibiotic Prophylaxis Assessment

2.2.4. Quality of SSI Preventive Measures

2.2.5. Follow-Up and Outcome Assessment

2.3. IT and Statistics

2.3.1. Data Collection and Management

2.3.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.4. Data Quality Standards

2.3.5. Quality Assurance and Validation

2.4. Ethics and Governance

2.4.1. Ethical Considerations

2.4.2. Data Protection and Confidentiality

2.4.3. Governance Structure

2.4.4. Publication and Authorship

2.4.5. End of Audit Definition

3. Discussion

3.1. Implications for AMS and Clinical Practice

3.2. Strengths and Weaknesses

3.3. Further Research

4. Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| AP | Antibiotic prophylaxis |

| ABU | Asymptomatic bacteriuria |

| AWaRe | Access, Watch, Reserve (WHO classification) |

| BSI | Bloodstream infection |

| CAUTI | Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection |

| CHG | Chlorhexidine gluconate |

| CPIC | Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium |

| DEEP-URO | De-escalation of AP in Urological Procedures |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| eCRF | Electronic case report form |

| EHR | Electronic health record |

| GPIU | Global Prevalence of Infections in Urology |

| HAI | Healthcare-associated infection |

| HAUTI | Healthcare-associated urinary tract infection |

| ICMJE | International Committee of Medical Journal Editors |

| IPC | Infection Prevention and Control |

| LP | Laparoscopic Prostatectomy |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary team |

| NAL | National audit lead |

| RALP | Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy |

| RA/LP | Robot-Assisted/Laparoscopic Prostatectomy |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

| SSI | Surgical site infection |

| TWOC | Trial Without Catheter |

| UCL | University College London |

| UTI | Urinary tract infection |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- de la santé, O.M. (Ed.) Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance; World Health Organization: Genève, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 978-92-4-156474-8. [Google Scholar]

- Allegranzi, B.; Bischoff, P.; De Jonge, S.; Kubilay, N.Z.; Zayed, B.; Gomes, S.M.; Abbas, M.; Atema, J.J.; Gans, S.; Van Rijen, M.; et al. New WHO Recommendations on Preoperative Measures for Surgical Site Infection Prevention: An Evidence-Based Global Perspective. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, e276–e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bootsma, A.M.J.; Laguna Pes, M.P.; Geerlings, S.E.; Goossens, A. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Urologic Procedures: A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2008, 54, 1270–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkensammer, E.; Erenler, E.; Johansen, T.E.B.; Tzelves, L.; Schneidewind, L.; Yuan, Y.; Cai, T.; Koves, B.; Tandogdu, Z. Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çek, M.; Tandoğdu, Z.; Naber, K.; Tenke, P.; Wagenlehner, F.; Van Oostrum, E.; Kristensen, B.; Bjerklund Johansen, T.E. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Urology Departments, 2005–2010. Eur. Urol. 2013, 63, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/urological-infections (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- The Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, 2025: WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) Classification of Antibiotics for Evaluation and Monitoring of Use. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/B09489 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- The History of Aarhus University in 25 Sections/The University’s Seal. Available online: https://auhist.au.dk/en/25kapitlerafuniversitetetshistorie/theuniversity%27sseal (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Moschini, M.; Gandaglia, G.; Fossati, N.; Dell’Oglio, P.; Cucchiara, V.; Luzzago, S.; Zaffuto, E.; Suardi, N.; Damiano, R.; Shariat, S.F.; et al. Incidence and Predictors of 30-Day Readmission After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2017, 15, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merhe, A.; Abou Heidar, N.; Hout, M.; Bustros, G.; Mailhac, A.; Tamim, H.; Wazzan, W.; Bulbul, M.; Nasr, R. An Evaluation of the Timing of Surgical Complications Following Radical Prostatectomy: Data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP). Arab. J. Urol. 2020, 18, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstedt Lantz, A.; Stranne, J.; Tyritzis, S.I.; Bock, D.; Wallin, D.; Nilsson, H.; Carlsson, S.; Thorsteinsdottir, T.; Gustafsson, O.; Hugosson, J.; et al. 90-Day Readmission after Radical Prostatectomy-a Prospective Comparison between Robot-Assisted and Open Surgery. Scand. J. Urol. 2019, 53, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björklund, J.; Stattin, P.; Rönmark, E.; Aly, M.; Akre, O. The 90-Day Cause-Specific Mortality after Radical Prostatectomy: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. BJU Int. 2022, 129, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandoğdu, Z.; Bartoletti, R.; Cai, T.; Çek, M.; Grabe, M.; Kulchavenya, E.; Köves, B.; Menon, V.; Naber, K.; Perepanova, T.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Urosepsis: Outcomes from the Multinational, Multicenter Global Prevalence of Infections in Urology (GPIU) Study 2003–2013. World J. Urol. 2016, 34, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneman, N.; Low, D.E.; McGeer, A.; Green, K.A.; Fisman, D.N. At the Threshold: Defining Clinically Meaningful Resistance Thresholds for Antibiotic Choice in Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Point Prevalence Survey of Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use in European Acute Care Hospitals: Protocol Version 5.3: ECDC PPS 2016–2017; Publications Office LU: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangram, A.J.; Horan, T.C.; Pearson, M.L.; Silver, L.C.; Jarvis, W.R. Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am. J. Infect. Control 1999, 27, 97–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Urology Today: April/May 2023. Available online: https://online.flippingbook.com/view/257304614?sharedOn= (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- UTISOLVE. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/company/utisolveresearch/posts/?feedView=all (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Williams, B. The National Early Warning Score: From Concept to NHS Implementation. Clin. Med. 2022, 22, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.M.; Fink, M.P.; Marshall, J.C.; Abraham, E.; Angus, D.; Cook, D.; Cohen, J.; Opal, S.M.; Vincent, J.-L.; Ramsay, G. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Intensive Care Med. 2003, 29, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recommendations|Sepsis: Recognition, Diagnosis and Early Management|Guidance|NICE. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG51/chapter/Recommendations#identifying-people-with-suspected-sepsis (accessed on 26 October 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Falkensammer, E.; Köves, B.; Wagenlehner, F.; Medina-Polo, J.; Tapia-Herrero, A.-M.; Day, E.; Stangl, F.; Schneidewind, L.; Kranz, J.; Bjerklund Johansen, T.E.; et al. Development of DEEP-URO, a Generic Research Tool for Enhancing Antimicrobial Stewardship in a Surgical Specialty. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010074

Falkensammer E, Köves B, Wagenlehner F, Medina-Polo J, Tapia-Herrero A-M, Day E, Stangl F, Schneidewind L, Kranz J, Bjerklund Johansen TE, et al. Development of DEEP-URO, a Generic Research Tool for Enhancing Antimicrobial Stewardship in a Surgical Specialty. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010074

Chicago/Turabian StyleFalkensammer, Eva, Béla Köves, Florian Wagenlehner, José Medina-Polo, Ana-María Tapia-Herrero, Elizabeth Day, Fabian Stangl, Laila Schneidewind, Jennifer Kranz, Truls Erik Bjerklund Johansen, and et al. 2026. "Development of DEEP-URO, a Generic Research Tool for Enhancing Antimicrobial Stewardship in a Surgical Specialty" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010074

APA StyleFalkensammer, E., Köves, B., Wagenlehner, F., Medina-Polo, J., Tapia-Herrero, A.-M., Day, E., Stangl, F., Schneidewind, L., Kranz, J., Bjerklund Johansen, T. E., & Tandogdu, Z., on behalf of the UTISOLVE Research Group. (2026). Development of DEEP-URO, a Generic Research Tool for Enhancing Antimicrobial Stewardship in a Surgical Specialty. Antibiotics, 15(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010074