Functional Characterization of ycao in Escherichia coli C91 Reveals Its Role in Siderophore Production, Iron-Limited Growth, and Antimicrobial Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

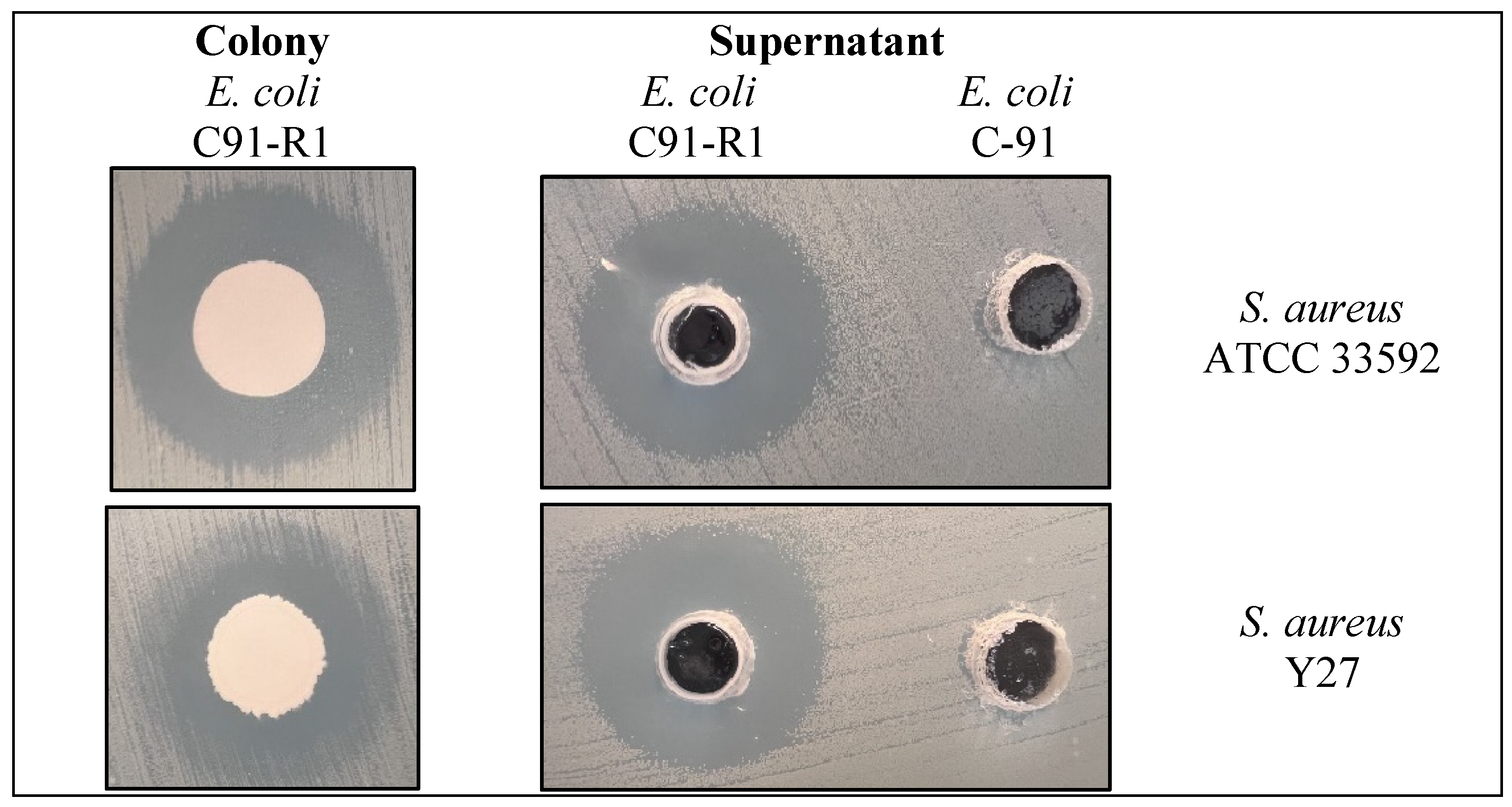

2.1. Production of Antimicrobials by E. coli C91 and E. coli C91-R1

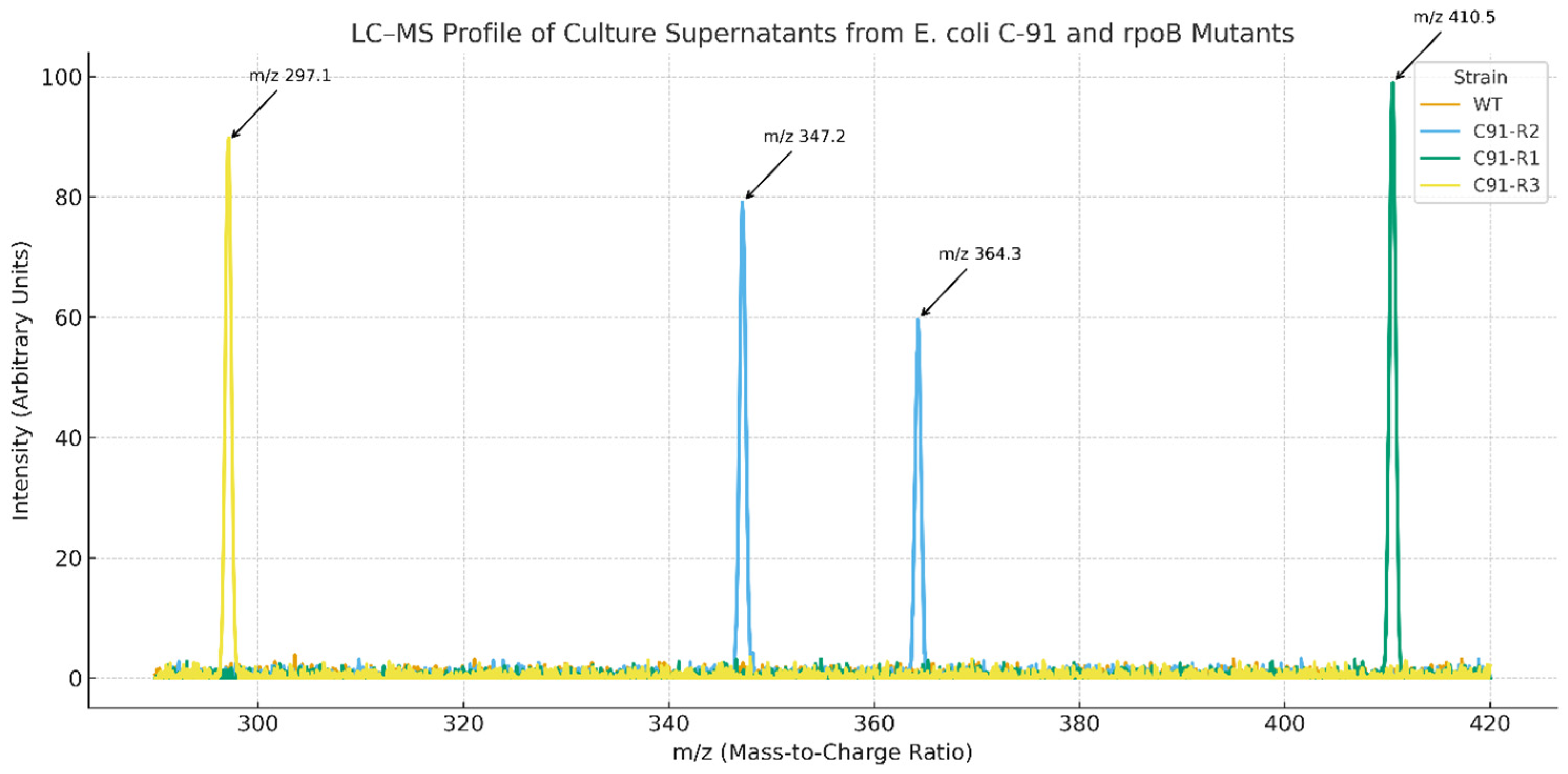

2.2. LC-MS of Supernatants

2.3. CAS Assay for Siderophore Production

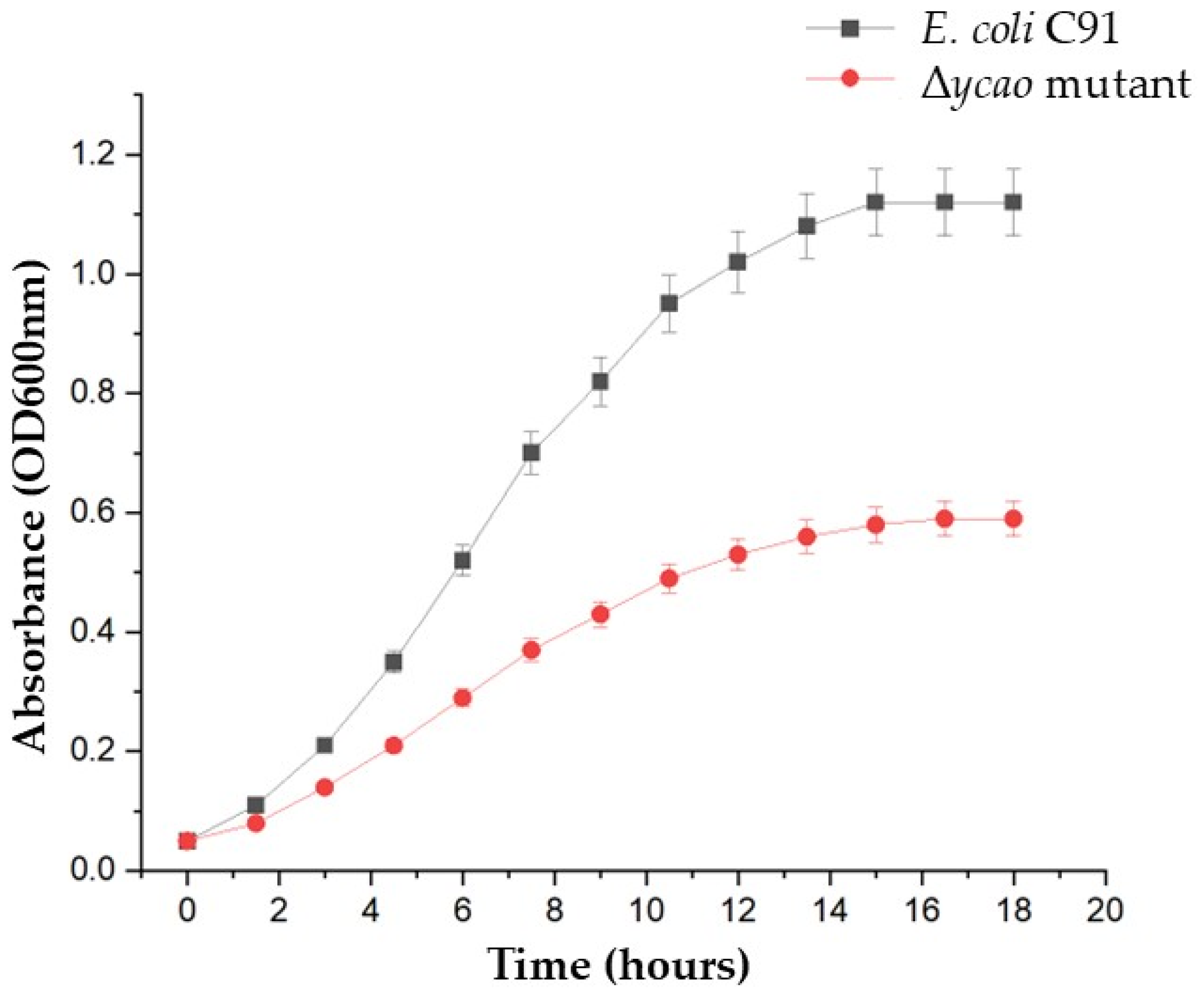

2.4. Growth Under Iron-Limiting Conditions

2.5. Generation and Molecular Confirmation of the Δycao Mutant

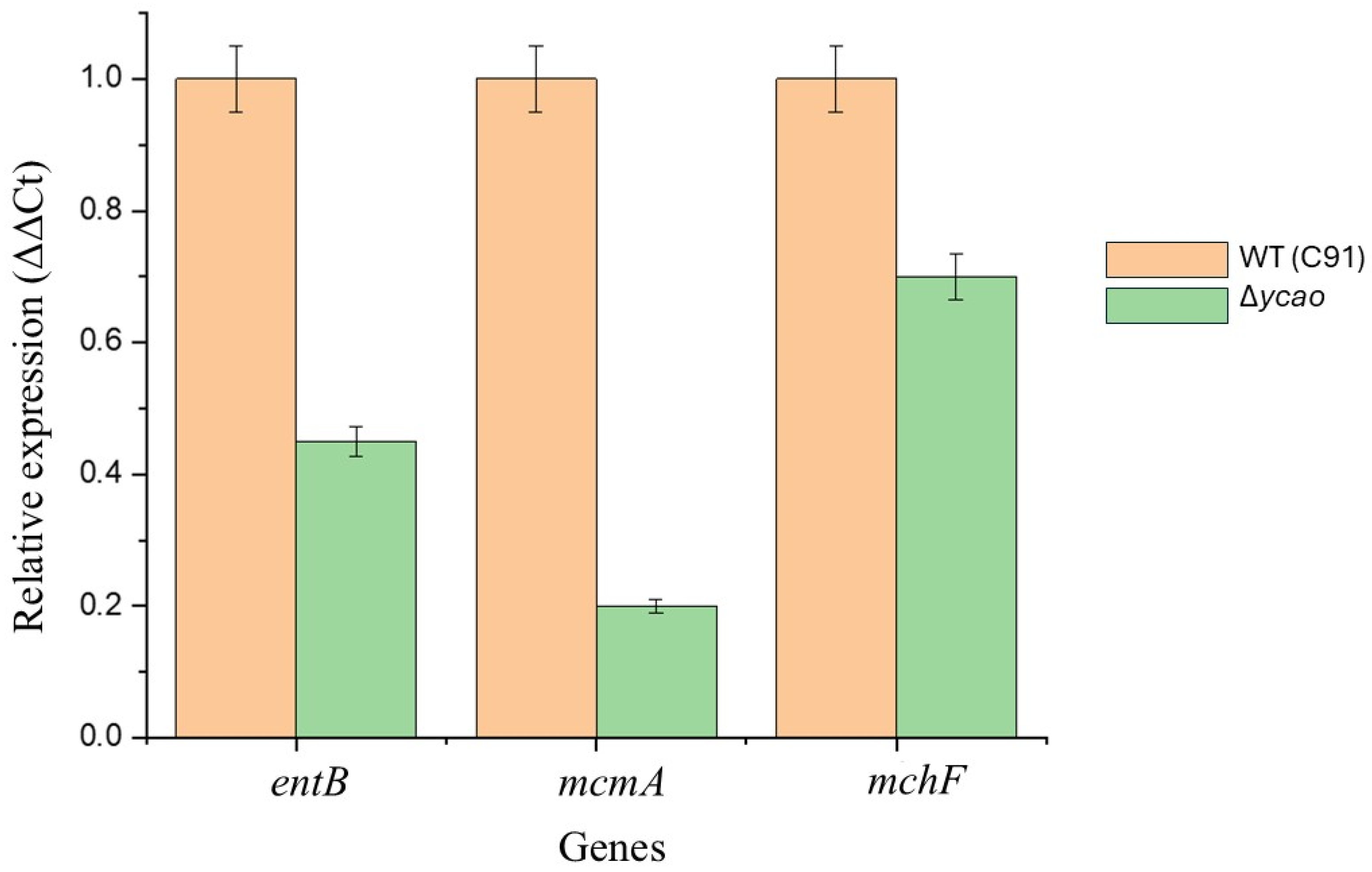

2.6. Transcription Analysis

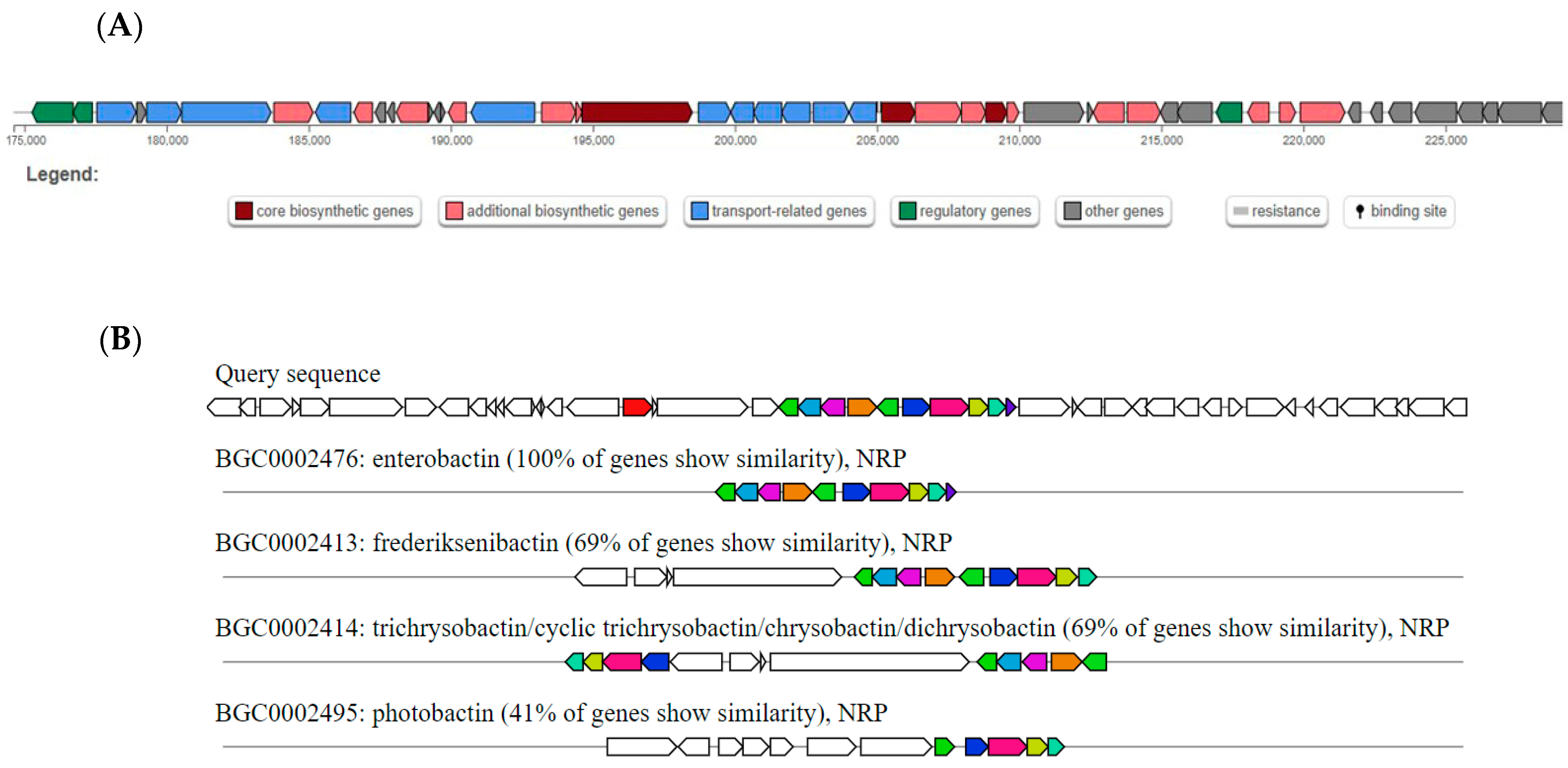

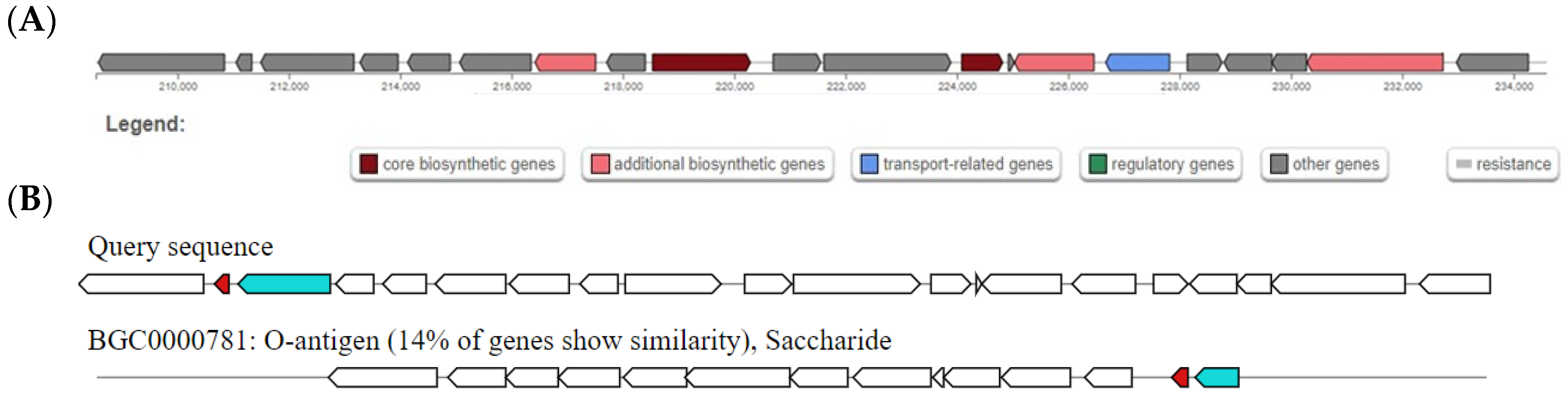

2.7. Prediction of Genes Coding for Possible Antibacterial Compounds in the Genome of E. coli C91

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strain and Culture Conditions

4.2. Assays for Antibiotic Production by E. coli C91

4.2.1. Agar-Well Diffusion Assays

4.2.2. Spot-on-Lawn Assay

4.3. Determination of MICs

4.4. Selection of Rifampicin-Resistant E. coli C91 Mutants

4.5. DNA Extraction, Amplification and Sequencing

4.6. Analysis of Antibiotic Production by Mutant Strains of E. coli C91

4.7. Generation of ycao Deletion Mutant in E. coli C91

4.8. Chrome Azurol (CAS) Assay

4.9. Growth Assays Under Iron-Limiting Conditions

4.10. LC-MS Analysis of Culture Supernatant

4.11. Transcriptional Analysis by Real-Time qPCR

4.12. In Silico Prediction of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| antiSMASH | Antibiotics and Secondary Metabolites Analysis Shell |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BAGEL4 | BActeriocin GEnome mining tool |

| BGC | Biosynthetic gene cluster |

| BPC | Base peak chromatograms |

| CAS | Chrome Azurol S |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CFS | Cell-free supernatant |

| CNF1 | Cytotoxicity necrotizing factor 1 |

| HPLC | High-performance Liquid Chromatography |

| EIC | Extracted ion chromatogram |

| Fur | Ferric uptake regulator |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| NP | Natural product |

| PRISM | PRediction Informatics for Secondary Metabolomes |

| rpm | Rotations per minute |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time PCR |

| SM | Secondary metabolite |

| SPE | Solid phase extraction |

| SPSS | Statistical Packages for Social Sciences |

| UPEC | Uropathogenic E. coli |

| VRE | Vancomycin-resistant enterococci |

| WGS | Whole genome sequence |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Boucher, H.W.; Talbot, G.H.; Bradley, J.S.; Edwards, J.E.; Gilbert, D.; Rice, L.B.; Scheld, M.; Spellberg, B.; Bartlett, J. Bad bugs, no drugs: No ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, J.; Reyneke, B.; Waso-Reyneke, M.; Havenga, B.; Barnard, T.; Khan, S.; Khan, W. Prevalence of ESKAPE pathogens in the environment: Antibiotic resistance status, community-acquired infection and risk to human health. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 244, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tängdén, T.; Giske, C.G. Global dissemination of extensively drug-resistant carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: Clinical perspectives on detection, treatment, and infection control. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 283, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. Platforms for antibiotic discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radajewski, S.; Webster, G.; Reay, D.S.; Morris, S.A.; Ineson, P.; Nedwell, D.B.; Prosser, J.I.; Murrell, J.C. Identification of active methylotroph populations in an acidic forest soil by stable-isotope probing. Microbiology 2002, 148, 2331–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipperer, A.; Konnerth, M.C.; Laux, C.; Berscheid, A.; Janek, D.; Weidenmaier, C.; Burian, M.; Schilling, N.A.; Slavetinsky, C.; Marschal, M.; et al. Human commensals producing a novel antibiotic impair pathogen colonization. Nature 2016, 535, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimermancic, P.; Medema, M.H.; Claesen, J.; Kurita, K.; Wieland Brown, L.C.; Mavrommatis, K.; Pati, A.; Godfrey, P.A.; Koehrsen, M.; Clardy, J.; et al. Insights into secondary metabolism from a global analysis of prokaryotic biosynthetic gene clusters. Cell 2014, 158, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malit, J.J.L.; Leung, H.Y.C.; Qian, P.Y. Targeted Large-Scale Genome Mining and Candidate Prioritization for Natural Product Discovery. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Steinke, K.; Villebro, R.; Ziemert, N.; Lee, S.; Medema, M.; Weber, T. antiSMASH 5.0: Updates to the secondary metabolite genome mining pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W81–W87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinnider, M.; Merwin, N.; Johnston, C.; Magarvey, N. PRISM 3: Expanded prediction of natural product chemical structures from microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W49–W54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zheng, L.; Gong, Z.; Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chi, M. Urinary tract infections caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli: Mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touchon, M.; Hoede, C.; Tenaillon, O.; Barbe, V.; Baeriswyl, S.; Bidet, P.; Bingen, E.; Bonacorsi, S.; Bouchier, C.; Bouvet, O.; et al. Organised genome dynamics in the Escherichia coli species results in highly diverse adaptive paths. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azimzadeh, P.N.; Birchenough, G.M.; Gualbuerto, N.C.; Pinkner, J.S.; Tamadonfar, K.O.; Beatty, W.; Hannan, T.J.; Dodson, K.W.; Ibarra, E.C.; Kim, S.; et al. Mechanisms of uropathogenic E. coli mucosal association in the gastrointestinal tract. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadp7066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlizzi, M.E.; Gribaudo, G.; Maffei, M.E. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) infections: Virulence factors, bladder responses, antibiotic resistance, and the unmet need for new therapeutic strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.E.; Heffernan, J.R.; Henderson, J.P. The iron hand of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: The role of transition metal control in virulence. Future Microbiol. 2018, 13, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Walker, J.N.; Caparon, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary tract infections: Epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owrangi, B.; Masters, N.; Kuballa, A.; O’Dea, C.; Vollmerhausen, T.L.; Katouli, M. Invasion and translocation of uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from urosepsis and patients with community-acquired urinary tract infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maan, H.; Itkin, M.; Malitsky, S.; Friedman, J.; Kolodkin-Gal, I. Resolving the conflict between antibiotic production and rapid growth by recognition of peptidoglycan of susceptible competitors. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miethke, M.; Marahiel, M.A. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007, 71, 413–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Hantke, K. Recent insights into iron import by bacteria. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011, 15, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlitni, S.; Ferruccio, L.F.; Brown, E.D. Metabolic suppression identifies new antibacterial inhibitors under nutrient limitation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.B.; Wilson, I.D.; Nicholls, A.W.; Broadhurst, D. The importance of experimental design and quality control in large-scale and MS-based metabolomics. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 5437–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, N.; Silhavy, T.J. How Escherichia coli Became the Flagship Bacterium of Molecular Biology. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 20, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherlach, K.; Hertweck, C. Mining and unearthing hidden biosynthetic potential. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, K.; Hosaka, T. New strategies for drug discovery: Activation of silent or weakly expressed microbial gene clusters. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, A.A.; Vali, L.; Shamsah, S.; Jadaon, M.; ElShazly, S. Genomic Characteristics of an Extensive-Drug-Resistant Clinical Escherichia coli O99 H30 ST38 Recovered from Wound. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2024, 23, e143910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Park, S.Y.; Park, Y.S.; Eun, H.; Lee, S.Y. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for natural product biosynthesis. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 745–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farha, M.A.; Tu, M.M.; Brown, E.D. Important challenges to finding new leads for new antibiotics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2024, 83, 102562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavituna, F.; Luti, K.J.; Gu, L. In search of the E. coli compounds that change the antibiotic production pattern of Streptomyces coelicolor during inter-species interaction. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2016, 90, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Y.; Soni, V.; Rhee, K.Y.; Helmann, J.D. Mutations in rpoB That Confer Rifampicin Resistance Can Alter Levels of Peptidoglycan Precursors and Affect β-Lactam Susceptibility. mBio 2023, 25, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, S.R.; Kerdel, Y.; Gathot, J.; Rigali, S. The Transcriptional Architecture of Bacterial Biosynthetic Gene Clusters. bioRxiv 2025, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.D. Opportunities for natural products in 21st century antibiotic discovery. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.A.; Korzheva, N.; Mustaev, A.; Murakami, K.; Nair, S.; Goldfarb, A.; Darst, S.A. Structural mechanism for rifampicin inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase. Cell 2001, 104, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, M.F.; Summers, S.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Zacharia, V.M.; Hightower, G.A.; Smith, J.T.; Conway, T. The global, ppGpp-mediated stringent response to amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 68, 1128–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reen, F.J.; Romano, S.; Dobson, A.D.W.; O’Gara, F. The Sound of Silence: Activating Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Marine Microorganisms. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 4754–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerinot, M.L. Microbial iron transport. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1994, 48, 743–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.C.; Robinson, A.K.; Rodríguez-Quiñones, F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duquesne, S.; Destoumieux-Garzón, D.; Peduzzi, J.; Rebuffat, S. Microcins, gene-encoded antibacterial peptides from enterobacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007, 24, 708–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, S.W.; Kim, D.; Szubin, R.; Palsson, B.O. Genome-wide reconstruction of OxyR and SoxRS transcriptional regulatory networks under oxidative stress in E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 5089–5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcheron, G.; Dozois, C.M. Interplay between iron homeostasis and virulence: Fur and RyhB as major regulators of bacterial pathogenicity. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 31, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amankwah, F.K.D.; Gbedema, S.Y.; Boakye, Y.D.; Bayor, M.T.; Boamah, V.E. Antimicrobial Potential of Extract from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolate. Scientifica 2022, 2022, 4230397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgas, C.; De Souza, S.M.; Smânia, E.F.A.; Smânia, A., Jr. Screening methods to determine antibacterial activity of natural products. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2007, 38, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coman, M.M.; Verdenelli, M.C.; Cecchini, C.; Silvi, S.; Orpianesi, C.; Boyko, N.; Cresci, A. In vitro evaluation of antimicrobial activity of Lactobacillus rhamnosus IMC 501®, Lactobacillus paracasei IMC 502® and SYNBIO® against pathogens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaluso, G.; Fiorenza, G.; Gaglio, R.; Mancuso, I.; Scatassa, M.L. In Vitro Evaluation of Bacteriocin-Like Inhibitory Substances Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated During Traditional Sicilian Cheese Making. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2016, 5, 5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (CLSI), 30th ed.; CLSI supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko, K.A.; Wanner, B.L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 6640–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwyn, B.; Neilands, J.B. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 160, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagg, A.; Neilands, J.B. Ferric uptake regulation protein acts as a repressor, employing iron (II) as a cofactor to bind the operator of an iron transport operon in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 1987, 26, 5471–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernbom, N.; Ng, Y.Y.; Kjelleberg, S.; Harder, T.; Gram, L. Marine bacteria from Danish coastal waters show antifouling activity against the marine fouling bacterium Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain S91 and zoospores of the green alga Ulva australis independent of bacteriocidal activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 8557–8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, D.; Müller, R. Secondary metabolomics: The impact of mass spectrometry-based approaches on the discovery and characterization of microbial natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 768–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | Zone of Inhibition a (mm) | Rifampicin Resistance (µg/mL) | Mutation Detected (rpoB) | Reference or Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus Y27 | S. aureus ATCC 33592 | ||||

| E. coli C91 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | <5 | None | [28] |

| E. coli C91-R1 | 19 ± 0.72 | 20 ± 0.59 | >200 | S531L | This study |

| E. coli C91-R2 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | >200 | H526Y | This study |

| E. coli C91-R3 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | >200 | D516V | This study |

| Sample | New Peaks Detected (m/z) | Putative Compound Matched |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli C91 (WT) | None | - |

| E. coli C91-R1 | 410.5 | Non-ribosomal peptide-like compound |

| E. coli C91-R2 | 347.2, 364.3 | Possible polyketide or peptide |

| E. coli C91-R3 | 297.1 | Novel metabolite (no database match) |

| Strain | Siderophore Production (mm) | Relative Siderophore Units (RSU) * |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli C91 (wild type) | 14.2 ± 0.4 | 100% |

| Δycao (mutant) | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 39% |

| Growth Condition | Strain | Final OD600nm | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron replete (control) | E. coli C91 (WT) | 1.12 ± 0.04 | 9.11 ± 0.12 |

| Δycao mutant | 1.09 ± 0.03 | 8.88 ± 0.23 * | |

| Iron-limited | E. coli C91 (WT) | 1.0 ± 0.04 | 8.89 ± 0.15 |

| Δycao mutant | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 5.54 ± 0.35 ** |

| Tool | Cluster a | Type | Most Similar Known Cluster b | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | 1 | NRP | Enterobactin BGC | 100 |

| Frederiksenibactin BGC | 69 | |||

| Trichryobactin BGC | 69 | |||

| Photobactin BGC | 41 | |||

| antiSMASH | 2 | Thiopeptide | O-antigen BGC | 14 |

| PRISM | 1 | Polyketide | - | - |

| Indicator Organism | Phenotype of Resistance * | Institute/Company |

|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ADA 100 | AMP, COL, CAZ, TET | Medical Laboratory Sciences, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, Kuwait University |

| Acinetobacter baumannii ADA 155 | AMP, CTX, CAZ, CH, TET | |

| Staphylococcus aureus Y27 | MET, VA | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae ATCC 13813 | GM, MET | American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 33592 | VA, CIP, GM, MET |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dashti, K.M.; Ebrahim, H.; Vali, L.; Dashti, A.A. Functional Characterization of ycao in Escherichia coli C91 Reveals Its Role in Siderophore Production, Iron-Limited Growth, and Antimicrobial Activity. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010043

Dashti KM, Ebrahim H, Vali L, Dashti AA. Functional Characterization of ycao in Escherichia coli C91 Reveals Its Role in Siderophore Production, Iron-Limited Growth, and Antimicrobial Activity. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleDashti, Khadijah M., H. Ebrahim, Leila Vali, and Ali A. Dashti. 2026. "Functional Characterization of ycao in Escherichia coli C91 Reveals Its Role in Siderophore Production, Iron-Limited Growth, and Antimicrobial Activity" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010043

APA StyleDashti, K. M., Ebrahim, H., Vali, L., & Dashti, A. A. (2026). Functional Characterization of ycao in Escherichia coli C91 Reveals Its Role in Siderophore Production, Iron-Limited Growth, and Antimicrobial Activity. Antibiotics, 15(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010043