The Other Face of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in Hospitalized Patients: Insights from over Two Decades of Non-Cystic Fibrosis Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Demographic and Clinical Data

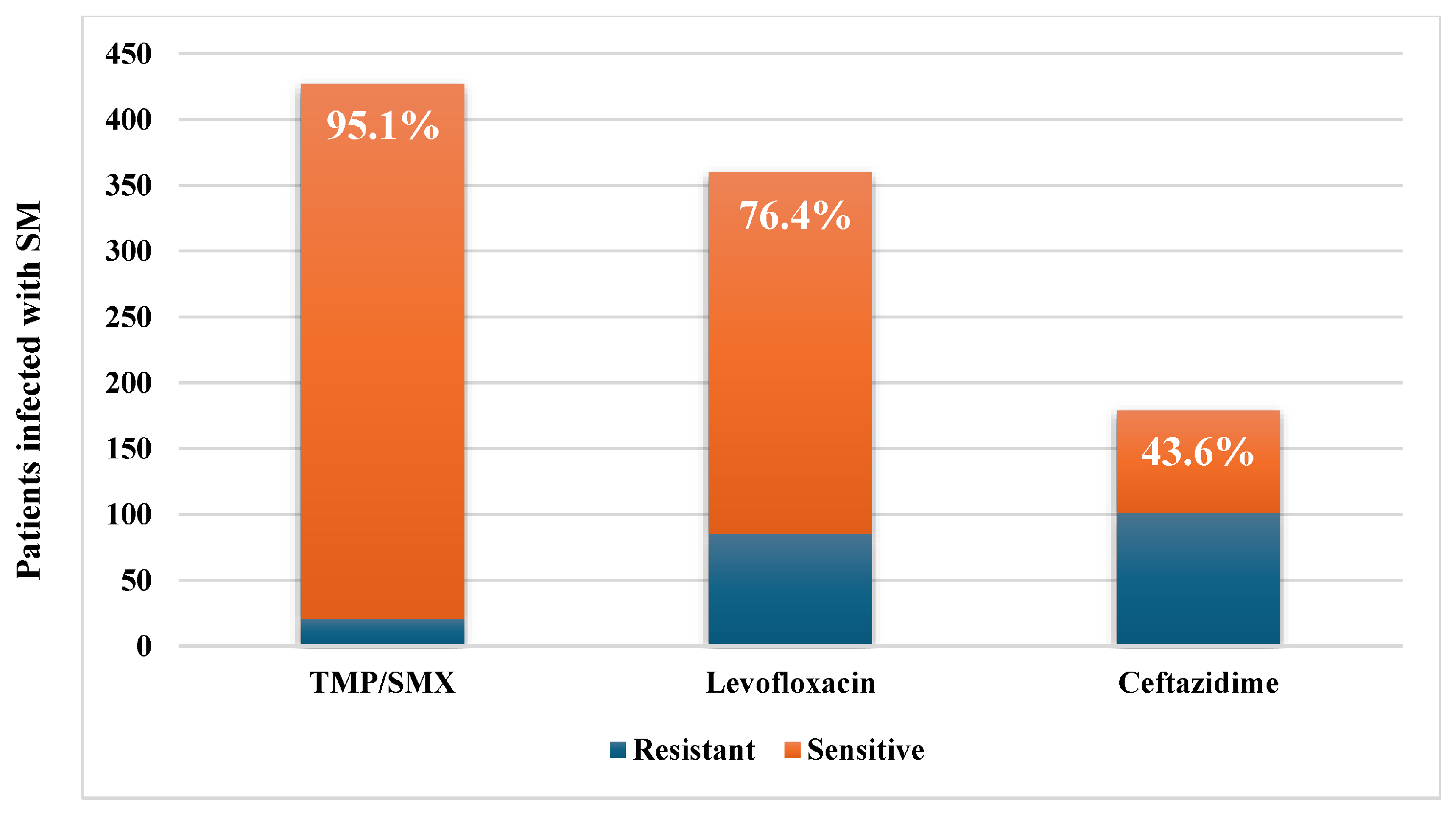

2.2. Microbiological Data

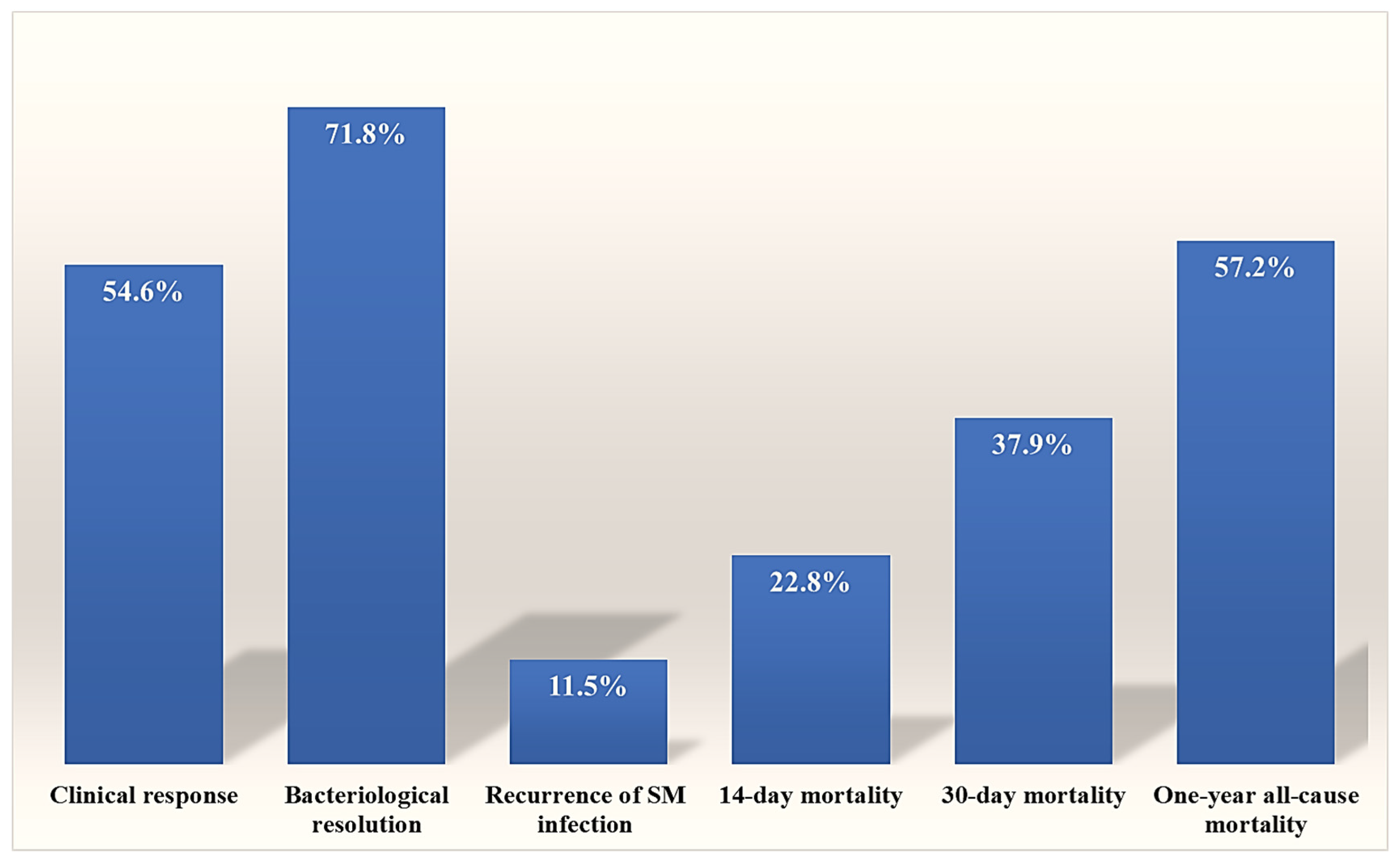

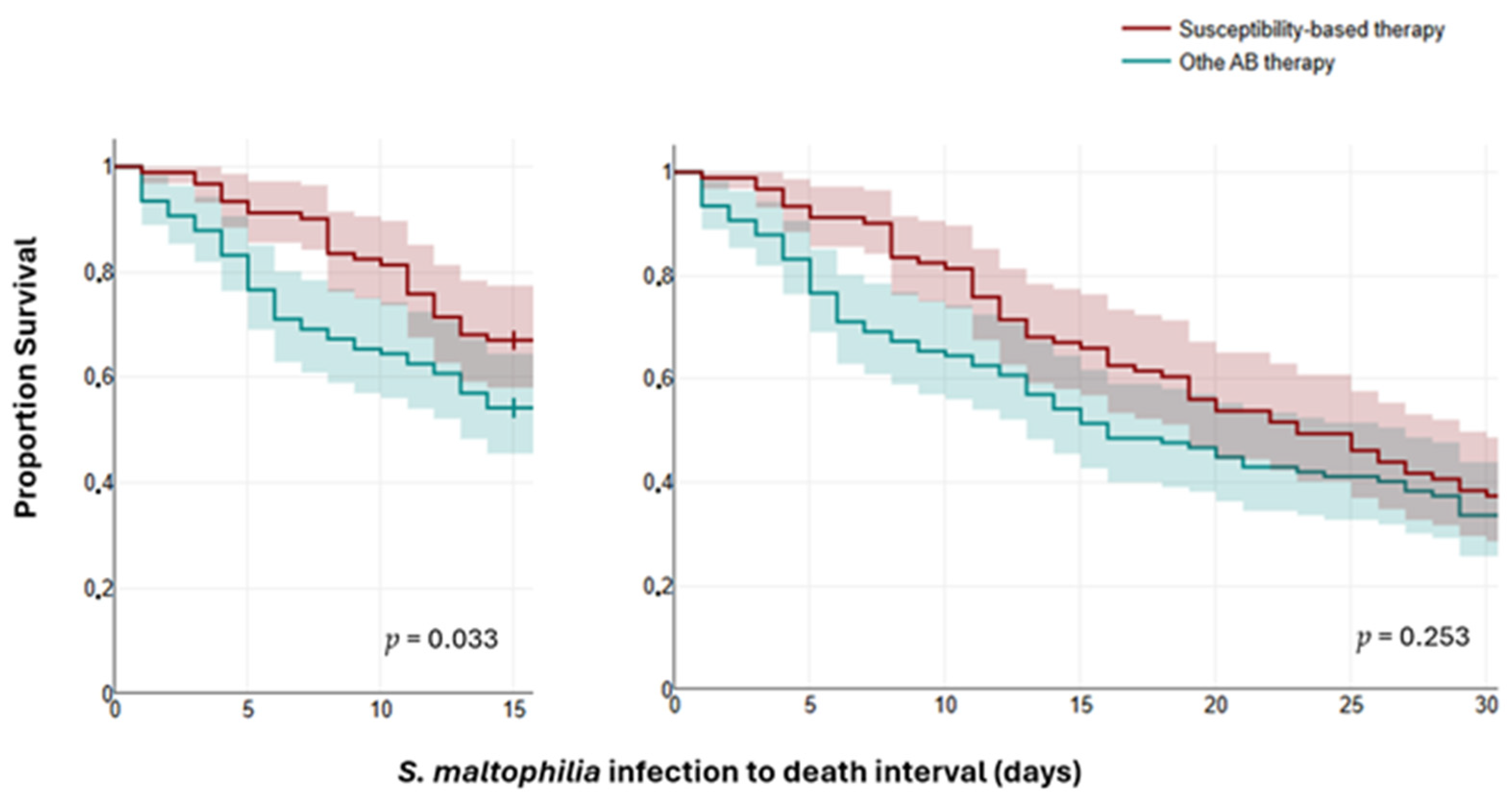

2.3. Outcomes and Mortality Predictors

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

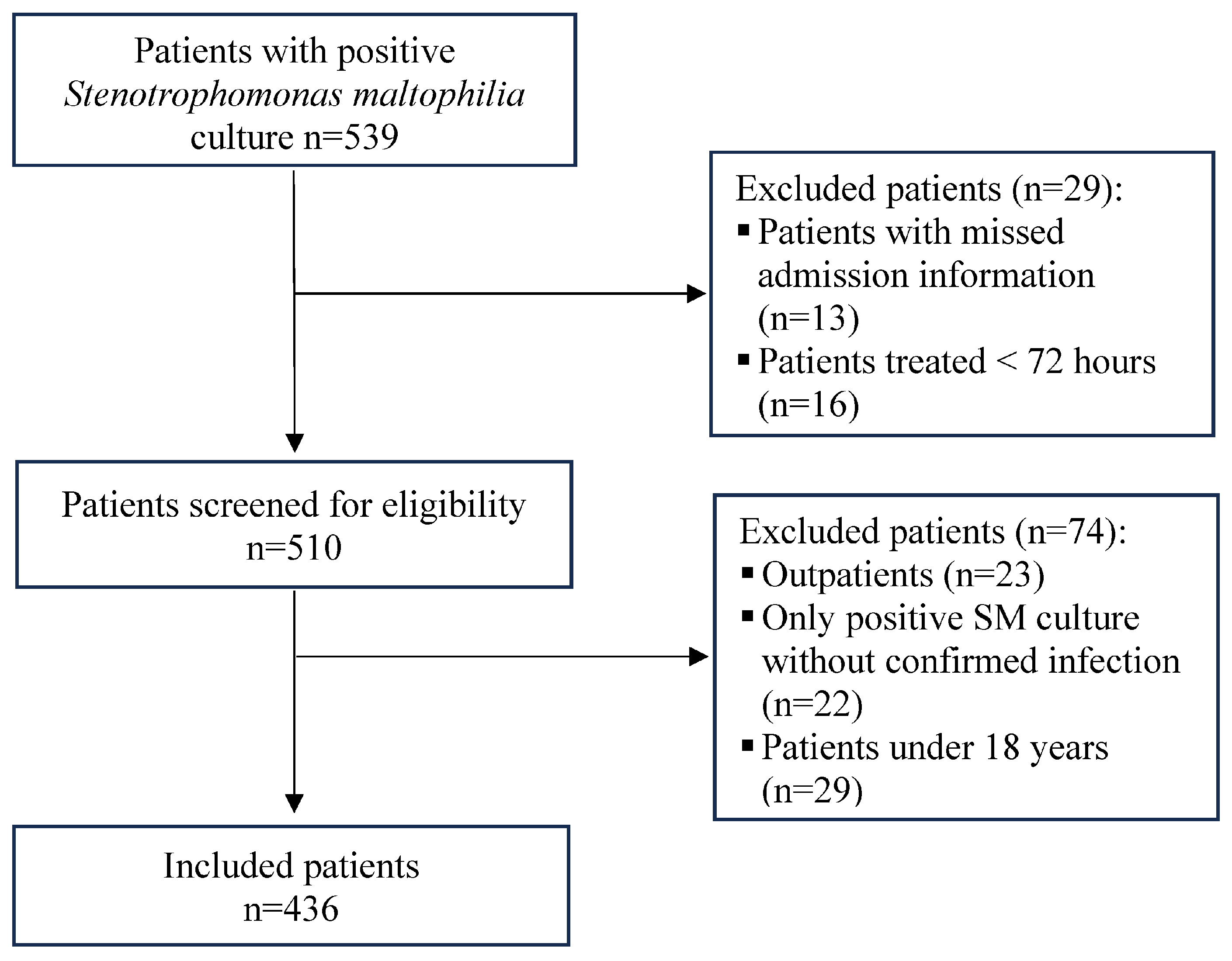

4.1. Study Design, Settings, and Participants

- Adult ≥ 18.

- Clinically diagnosed S. maltophilia infection (not colonization).

- Receipt of directed antimicrobial therapy ≥ 72 h.

- The key admission data were missing.

- They were managed as outpatients.

4.2. Demographics and Clinical Data Collection

4.3. Microbiological Procedures

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APACHE | Acute Physiological Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation |

| aPTT | Activated partial thromboplastin time |

| AST | Antimicrobial susceptibility testing |

| BSI | bloodstream infections |

| CF | Cystic fibrosis |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| HAP | Hospital-acquired pneumonia |

| ICU | intensive care unit |

| PT | prothrombin time |

| SOFA | Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| TMP-SMX | Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole |

| UTIs | urinary tract infections |

| VAP | Ventilator-associated pneumonia |

References

- Chauviat, A.; Meyer, T.; Favre-Bonté, S. Versatility of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: Ecological Roles of RND Efflux Pumps. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J.S. Advances in the Microbiology of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34, e00030-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, D.J.; Rutala, W.A.; Blanchet, C.N.; Jordan, M.; Gergen, M.F. Faucet Aerators: A Source of Patient Colonization with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Am. J. Infect. Control 1999, 27, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, M.; Kerr, K.G. Microbiological and Clinical Aspects of Infection Associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Hsueh, P.-R. Update on Infections Caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia with Particular Attention to Resistance Mechanisms and Therapeutic Options. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlFonaisan, M.K.; Mubaraki, M.A.; Althawadi, S.I.; Obeid, D.A.; Al-Qahtani, A.A.; Almaghrabi, R.S.; Alhamlan, F.S. Temporal Analysis of Prevalence and Antibiotic-Resistance Patterns in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Clinical Isolates in a 19-Year Retrospective Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Kastoris, A.C.; Vouloumanou, E.K.; Rafailidis, P.I.; Kapaskelis, A.M.; Dimopoulos, G. Attributable Mortality of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infections: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Future Microbiol. 2009, 4, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettcher, S.R.; Kenney, R.M.; Arena, C.J.; Beaulac, A.E.; Tibbetts, R.J.; Shallal, A.B.; Suleyman, G.; Veve, M.P. Say It Ain’t Steno: A Microbiology Nudge Comment Leads to Less Treatment of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Respiratory Colonization. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2024, 46, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicodemo, A.C.; Paez, J.I.G. Antimicrobial Therapy for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007, 26, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erinmez, M.; Aşkın, F.N.; Zer, Y. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Outbreak in a University Hospital: Epidemiological Investigation and Literature Review of an Emerging Healthcare-Associated Infection. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2024, 66, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Gil, T.; Martínez, J.L.; Blanco, P. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: A Review of Current Knowledge. Expert. Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.B. Antibiotic Resistance in the Opportunistic Pathogen Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banar, M.; Sattari-Maraji, A.; Bayatinejad, G.; Ebrahimi, E.; Jabalameli, L.; Beigverdi, R.; Emaneini, M.; Jabalameli, F. Global Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance in Clinical Isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1163439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 35th ed.; CLSI supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tamma, P.D.; Heil, E.L.; Justo, J.A.; Mathers, A.J.; Satlin, M.J.; Bonomo, R.A. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2024 Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024; ciae403, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbek, M.; Aldemir, Ö.; Çakır Kıymaz, Y.; Baysal, C.; Yıldırım, D.; Büyüktuna, S.A. Mortality Rates and Risk Factors Associated with Mortality in Patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Primary Bacteraemia and Pneumonia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 111, 116664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gales, A.C.; Jones, R.N.; Forward, K.R.; Liñares, J.; Sader, H.S.; Verhoef, J. Emerging Importance of Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter Species and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia as Pathogens in Seriously Ill Patients: Geographic Patterns, Epidemiological Features, and Trends in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997–1999). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32, S104–S113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menekşe, Ş.; Altınay, E.; Oğuş, H.; Kaya, Ç.; Işık, M.E.; Kırali, K. Risk Factors for Mortality in Patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bloodstream Infections in Immunocompetent Patients. Infect. Dis. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 4, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lu, P.-L.; Lai, C.-C.; Chen, T.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Wu, D.-C.; Wang, T.-P.; Lin, C.-M.; Lin, W.-R.; et al. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bloodstream Infection: Comparison between Community-Onset and Hospital-Acquired Infections. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2014, 47, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insuwanno, W.; Kiratisin, P.; Jitmuang, A. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infections: Clinical Characteristics and Factors Associated with Mortality of Hospitalized Patients. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-L.; Chang, P.-H.; Liu, Y.-W.; Lai, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, I.-L.; Li, W.-F.; Wang, C.-C.; Lee, I.-K. Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections in Surgical Intensive Care Unit Patients Following Abdominal Surgery: High Mortality Associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infection. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2024, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, N.M.; Sahbudak Bal, Z.; Güner Özenen, G.; Yildirim Arslan, S.; Ozek, G.; Ozdemir Karadas, N.; Yazici, P.; Cilli, F.; Kurugöl, Z. Risk Factors for Infection and Mortality Associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bloodstream Infections in Children; Comparison with Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bloodstream Infections. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Rong, H.; Guo, Z.; Xu, J.; Huang, X. Risk Factors of Lower Respiratory Tract Infection Caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1035812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanuma, M.; Sakurai, T.; Nakaminami, H.; Tanaka, M. Risk Factors and Clinical Characteristics for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infection in an Acute Care Hospital in Japan: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2025, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saburi, M.; Oshima, K.; Takano, K.; Inoue, Y.; Harada, K.; Uchida, N.; Fukuda, T.; Doki, N.; Ikegame, K.; Matsuo, Y.; et al. Risk Factors and Outcome of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infection after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: JSTCT, Transplant Complications Working Group. Ann. Hematol. 2023, 102, 2507–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompilio, A.; Crocetta, V.; De Nicola, S.; Verginelli, F.; Fiscarelli, E.; Di Bonaventura, G. Cooperative Pathogenicity in Cystic Fibrosis: Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Modulates Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Virulence in Mixed Biofilm. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebara, H.; Hagiya, H.; Haruki, Y.; Kondo, E.; Otsuka, F. Clinical Characteristics of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bacteremia: A Regional Report and a Review of a Japanese Case Series. Intern. Med. 2017, 56, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gezer, Y.; Tayşi, M.R.; Tarakçı, A.; Gökçe, Ö.; Danacı, G.; Altunışık Toplu, S.; Erdal Karakaş, E.; Alkan, S.; Kuyugöz Gülbudak, S.; Şahinoğlu, M.S.; et al. Evaluation of Clinical Outcomes and Risk Factors Associated with Mortality in Patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bloodstream Infection: A Multicenter Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanasuwan, S.; Rongmuang, J.; Siripaitoon, P.; Kositpantawong, N.; Charoenmak, B.; Hortiwakul, T.; Nwabor, O.F.; Chusri, S. Clinical Characteristics, Outcomes, and Risk Factors for Mortality in Patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bacteremia. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Singh, P.; Sharad, N.; Kiro, V.V.; Malhotra, R.; Mathur, P. Infection Trends, Susceptibility Pattern, and Treatment Options for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infections in Trauma Patients: A Retrospective Study. J. Lab. Physicians 2023, 15, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, E.B.; Alby, K.; Bryson, A.L. Updates to Susceptibility Breakpoints for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. CLSI AST News Update 2025, 10. Available online: https://clsi.org/resources/insights/updates-to-susceptibility-breakpoints-for-stenotrophomonas-maltophilia/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Appaneal, H.J.; Lopes, V.V.; LaPlante, K.L.; Caffrey, A.R. Treatment, Clinical Outcomes, and Predictors of Mortality among a National Cohort of Hospitalized Patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infection. Public Health 2023, 214, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.; Slaven, B.; Clarke, L.G.; Ludwig, J.; Shields, R.K. Clinical and Microbiologic Outcomes of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bloodstream Infections. Infection 2025, 53, 1483–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwa, A.L.H.; Low, J.G.H.; Lim, T.P.; Leow, P.C.; Kurup, A.; Tam, V.H. Independent Predictors for Mortality in Patients with Positive Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Cultures. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2008, 37, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-L.; Liu, C.-E.; Ko, W.-C.; Hsueh, P.-R. In Vitro Susceptibilities of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Isolates to Antimicrobial Agents Commonly Used for Related Infections: Results from the Antimicrobial Testing Leadership and Surveillance (ATLAS) Program, 2004–2020. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2023, 62, 106878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Arias, C.A.; Abbott, A.; Dien Bard, J.; Bhatti, M.M.; Humphries, R.M. Evaluation of the Vitek 2, Phoenix, and MicroScan for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e00654-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.D.; Jeong, W.Y.; Kim, M.H.; Jung, I.Y.; Ahn, M.Y.; Ann, H.W.; Ahn, J.Y.; Han, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Song, Y.G.; et al. Risk Factors for Mortality in Patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bacteremia. Medicine 2016, 95, e4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raad, M.; Abou Haidar, M.; Ibrahim, R.; Rahal, R.; Abou Jaoude, J.; Harmouche, C.; Habr, B.; Ayoub, E.; Saliba, G.; Sleilaty, G.; et al. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Pneumonia in Critical COVID-19 Patients. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Lin, L.; Kuo, S. Risk Factors for Mortality in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bacteremia—A Meta-Analysis. Infect. Dis. 2024, 56, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.; Bartilotti Matos, F.; Gorgulho, A.; Gonçalves, C.; Figueiredo, C.; Coutinho, D.; Teixeira, T.; Pargana, M.; Abreu, G.; Malheiro, L. Determinants of Clinical Cure and Mortality in Patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infections: A Retrospective Analysis. Cureus 2025, 17, e86294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paez, J.I.G.; Costa, S.F. Risk Factors Associated with Mortality of Infections Caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: A Systematic Review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2008, 70, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Kim, Y.C.; Ahn, J.Y.; Jeong, S.J.; Ku, N.S.; Choi, J.Y.; Yeom, J.-S.; Song, Y.G. Risk Factors for Mortality in Patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bacteremia and Clinical Impact of Quinolone-Resistant Strains. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Xie, Z.; Chen, L. Risk Factors for Mortality in Hospitalized Patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bacteremia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 3881–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czosnowski, Q.A.; Wood, G.C.; Magnotti, L.J.; Croce, M.A.; Swanson, J.M.; Boucher, B.A.; Fabian, T.C. Clinical and Microbiologic Outcomes in Trauma Patients Treated for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. Pharmacotherapy 2011, 31, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, E.T.; Wardlow, L.; Ogake, S.; Bazan, J.A.; Coe, K.; Kuntz, K.; Elefritz, J.L. Comparison of Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole versus Minocycline Monotherapy for Treatment of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Pneumonia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nekidy, W.S.; Al Zaman, K.; Abidi, E.; Alrahmany, D.; Ghazi, I.M.; El Lababidi, R.; Mooty, M.; Hijazi, F.; Ghosn, M.; Askalany, M.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole in Critically Ill Patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Bacteremia and Pneumonia Utilizing Renal Replacement Therapies. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nys, C.; Cherabuddi, K.; Venugopalan, V.; Klinker, K.P. Clinical and Microbiologic Outcomes in Patients with Monomicrobial Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00788-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilmis, B.; Rouzaud, C.; To-Puzenat, D.; Gigandon, A.; Dauriat, G.; Feuillet, S.; Mitilian, D.; Issard, J.; Monnier, A.L.; Lortholary, O.; et al. Description, Clinical Impact and Early Outcome of S. Maltophilia Respiratory Tract Infections after Lung Transplantation, A Retrospective Observational Study. Respir. Med. Res. 2024, 86, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (N = 436) | Survivors (N = 305) | Non-Survivors (N = 131) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age (in years) * | 60.53 ± 19.31 | 59.96 ± 20.13 | 61.85 ± 17.24 | 0.350 |

| Gender (male) | 271 (62.2) | 195 (63.9) | 76 (58.0) | 0.234 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 170 (39.0) | 114 (37.4) | 56 (42.7) | 0.292 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 9 (2.1) | 7 (2.3) | 2 (1.5) | 0.605 |

| Renal failure | 96 (22.0) | 58 (19.0) | 38 (29.0) | 0.021 |

| Malignancy | 24 (5.5) | 16 (5.2) | 8 (6.1) | 0.724 |

| Site of infection acquisition | ||||

| Hospital-acquired | 405 (92.9) | 277 (90.8) | 128 (97.7) | 0.010 |

| Community-acquired | 31 (7.1) | 28 (9.2) | 3 (2.3) | |

| Infection type | ||||

| Bloodstream infection | 67 (15.4) | 43 (14.1) | 24 (18.3) | 0.262 |

| Pneumonia | 264 (60.6) | 177 (58.0) | 87 (66.4) | 0.101 |

| Urinary tract infection | 27 (6.2) | 21 (6.9) | 6 (4.6) | 0.360 |

| Skin and soft tissue infection | 34 (7.8) | 28 (9.2) | 6 (4.6) | 0.101 |

| Wound infection | 23 (5.3) | 18 (5.9) | 5 (3.8) | 0.372 |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 9 (2.1) | 7 (2.3) | 2 (1.5) | 0.605 |

| Central nervous system infection | 3 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 0.901 |

| Ear infection | 9 (2.1) | 9 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.047 |

| Hospital-acquired infection type | ||||

| Bloodstream infection | 65 (14.9) | 41 (13.4) | 24 (18.3) | 0.190 |

| Hospital-acquired pneumonia | 135 (31.0) | 99 (32.5) | 36 (27.5) | 0.303 |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 119 (27.3) | 70 (23.0) | 49 (37.4) | 0.002 |

| Urinary tract infection | 22 (5.0) | 16 (5.2) | 6 (4.6) | 0.771 |

| Skin and soft tissue infection | 28 (6.4) | 23 (7.5) | 5 (3.8) | 0.146 |

| Wound infection | 22 (5.0) | 17 (5.6) | 5 (3.8) | 0.442 |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 9 (2.1) | 7 (2.3) | 2 (1.5) | 0.605 |

| Central nervous system infection | 3 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 0.901 |

| Ear infection | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.353 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Previous hospitalization # | 151 (34.6) | 100 (32.8) | 51 (38.9) | 0.216 |

| Previous antibiotic therapy # | 241 (55.3) | 159 (52.1) | 82 (62.6) | 0.044 |

| ICU admission | 177 (40.6) | 96 (31.5) | 81 (61.8) | <0.001 |

| Central venous catheter | 103 (23.6) | 55 (18.0) | 48 (36.6) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 158 (36.2) | 87 (28.5) | 71 (54.2) | <0.001 |

| Concomitant infection | 242 (55.5) | 166 (54.4) | 76 (58.0) | 0.489 |

| Length of stay before S. maltophilia infection * | 29.40 ± 54.73 | 28.23 ± 57.4 | 32.12 ± 48.02 | 0.497 |

|

Survivors (N = 305)

(mean ± SD) |

Non-Survivors (N = 131)

(mean ± SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells | 11.50 ± 6.25 | 12.86 ± 8.25 | 0.068 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 71.97 ± 14.72 | 79.7 ± 13.96 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.13 ± 2.30 | 9.12 ± 1.72 | <0.001 |

| Platelets | 285.80 ± 147.1 | 180.70 ± 147.1 | <0.001 |

| Prothrombin time | 15.47 ± 5.31 | 19.08 ± 10.73 | <0.001 |

| Partial thromboplastin time | 36.30 ± 13.60 | 42.48 ± 24.81 | 0.002 |

| C-reactive protein | 8.85 ± 8.13 | 11.59 ± 7.87 | 0.017 |

| Procalcitonin | 3.12 ± 10.43 | 5.87 ± 12.15 | 0.163 |

| Total protein | 6.16 ± 1.53 | 5.58 ± 0.99 | <0.001 |

| Albumin | 2.65 ± 0.63 | 2.58 ± 0.59 | 0.247 |

| Aspartate transferase | 47.60 ± 60.89 | 91.65 ± 289.6 | 0.018 |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 51.27 ± 64.90 | 65.28 ± 113.0 | 0.139 |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 30.59 ± 26.11 | 47.17 ± 35.65 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine | 1.57 ± 1.90 | 1.93 ± 1.81 | 0.084 |

|

Total (N = 436) | Survivors (N = 305) | Non-Survivors (N = 131) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Concomitant isolated microbes | ||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 64 | 49 (16.1) | 15 (11.5) | 0.212 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 58 | 38 (12.5) | 20 (15.3) | 0.429 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 47 | 29 (9.5) | 18 (13.7) | 0.191 |

| Escherichia coli | 13 | 11 (3.6) | 2 (1.5) | 0.242 |

| Serratia marcescens | 20 | 12 (3.9) | 8 (6.1) | 0.320 |

| Enterobacter Species | 13 | 11 (3.6) | 2 (1.5) | 0.242 |

| Other Gram-negative | 14 | 12 (3.9) | 2 (1.5) | 0.191 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 14 | 11 (3.6) | 3 (2.3) | 0.475 |

| Other Staphylococci | 8 | 5 (1.6) | 3 (2.3) | 0.643 |

| Enterococcus Species | 13 | 9 (3.0) | 4 (3.1) | 0.954 |

| Candida Species | 24 | 15 (4.9) | 9 (6.9) | 0.413 |

| Antibacterial therapy | ||||

| Susceptibility-based AB therapy | 191 | 132 (43.3) | 59 (45.0) | 0.734 |

| Other AB therapy | 245 | 173 (56.7) | 72 (55.0) | |

| TMP-SMX monotherapy | 81 | 58 (19.0) | 23 (17.6) | 0.719 |

| Levofloxacin monotherapy | 49 | 32 (10.5) | 17 (13.0) | 0.451 |

| Ceftazidime monotherapy | 23 | 12 (3.9) | 11 (8.4) | 0.056 |

| TMP-SMX-Levofloxacin | 17 | 12 (3.9) | 5 (3.8) | 0.954 |

| TMP-SMX + Ceftazidime | 9 | 8 (2.6) | 1 (0.8) | 0.211 |

| Levofloxacin + Ceftazedime | 5 | 4 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) | 0.622 |

| TMP-SMX + Levofloxacin + Ceftazidime | 7 | 6 (2.0) | 1 (0.8) | 0.363 |

| AB therapy duration (mean ± SD) * | ||||

| TMP-SMX | 8.53 ± 5.72 | 9.51 ± 6.00 | 5.80 ± 3.73 | 0.002 |

| Levofloxacin | 8.24 ± 11.31 | 8.91 ± 13.17 | 6.75 ± 4.98 | 0.440 |

| Ceftazidime | 8.11 ± 7.79 | 8.67 ± 7.87 | 6.93 ± 7.75 | 0.497 |

| Univariable Logistic Regression | Multivariable Logistic Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Odds Ratio

(95% CI) | p-Value |

Adjusted Odds Ratio

(95% CI) | p-Value | |

| White blood cells | 1.027 (0.998–1.058) | 0.070 | 1.133 (1.052–1.220) | 0.001 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 1.045 (1.025–1.065) | <0.001 | 1.036 (1.003–1.070) | 0.034 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.745 (0.654–0.849) | <0.001 | 0.679 (0.510–0.903) | 0.008 |

| Platelets | 0.994 (0.993–0.996) | <0.001 | 0.994 (0.990–0.997) | 0.022 |

| Prothrombin time | 1.087 (1.043–1.134) | <0.001 | 1.086 (1.001–1.179) | 0.061 |

| Partial thromboplastin time | 1.018 (1.005–1.031) | 0.005 | 1.006 (0.987–1.026) | 0.256 |

| C-reactive protein | 1.041 (1.006–1.077) | 0.002 | 1.010 (0.963–1059) | 0.529 |

| Total Protein | 0.612 (0.489–0.765) | <0.001 | 0.887 (0.713–1.104) | 0.339 |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 1.018 (1.010–1.025) | <0.001 | 1.011 (0.997–1.024) | 0.111 |

| Univariable Logistic Regression | Multivariable Logistic Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identified Risk Factors | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

| Renal failure | 1.740 (1.084–2.794) | 0.022 | 1.640 (0.991–2.713) | 0.054 |

| Hospital-acquired | 4.313 (1.288–14.446) | 0.018 | 2.479 (0.699–8.793) | 0.160 |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 2.019 (1.305–3.123) | 0.002 | 0.522 (0.240–1.138) | 0.102 |

| Previous antibiotics | 1.537 (1.010–2.337) | 0.045 | 1.187 (0.753–1.871) | 0.460 |

| ICU admission | 3.527 (2.300–5.408) | <0.001 | 3.484 (1.466–8.276) | 0.005 |

| Central venous catheter | 2.629 (1.660–4.164) | <0.001 | 1.480 (0.882–2.484) | 0.137 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2.963 (1940–4.532) | <0.001 | 1.303 (0.465–3.652) | 0.615 |

| Levofloxacin monotherapy | 1.272 (0.679–2.383) | 0.452 | 1.197 (0.616–2.326) | 0.597 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alwazzeh, M.J.; Alnimr, A.; Alwarthan, S.M.; Alhajri, M.; Algazaq, J.; AlShehail, B.M.; Alnasser, A.H.; Alwail, A.T.; Alramadhan, K.M.; Alramadan, A.Y.; et al. The Other Face of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in Hospitalized Patients: Insights from over Two Decades of Non-Cystic Fibrosis Cohort. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010042

Alwazzeh MJ, Alnimr A, Alwarthan SM, Alhajri M, Algazaq J, AlShehail BM, Alnasser AH, Alwail AT, Alramadhan KM, Alramadan AY, et al. The Other Face of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in Hospitalized Patients: Insights from over Two Decades of Non-Cystic Fibrosis Cohort. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlwazzeh, Marwan Jabr, Amani Alnimr, Sara M. Alwarthan, Mashael Alhajri, Jumanah Algazaq, Bashayer M. AlShehail, Abdullah H. Alnasser, Ali Tahir Alwail, Komail Mohammed Alramadhan, Abdullah Yousef Alramadan, and et al. 2026. "The Other Face of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in Hospitalized Patients: Insights from over Two Decades of Non-Cystic Fibrosis Cohort" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010042

APA StyleAlwazzeh, M. J., Alnimr, A., Alwarthan, S. M., Alhajri, M., Algazaq, J., AlShehail, B. M., Alnasser, A. H., Alwail, A. T., Alramadhan, K. M., Alramadan, A. Y., Almulhim, F. A., Almulhim, G. A., Rahman, J. u., & Al-Hariri, M. T. (2026). The Other Face of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in Hospitalized Patients: Insights from over Two Decades of Non-Cystic Fibrosis Cohort. Antibiotics, 15(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010042