Lavandula angustifolia Essential Oil as a Developmental Inhibitor of Candida Species and Biofilms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

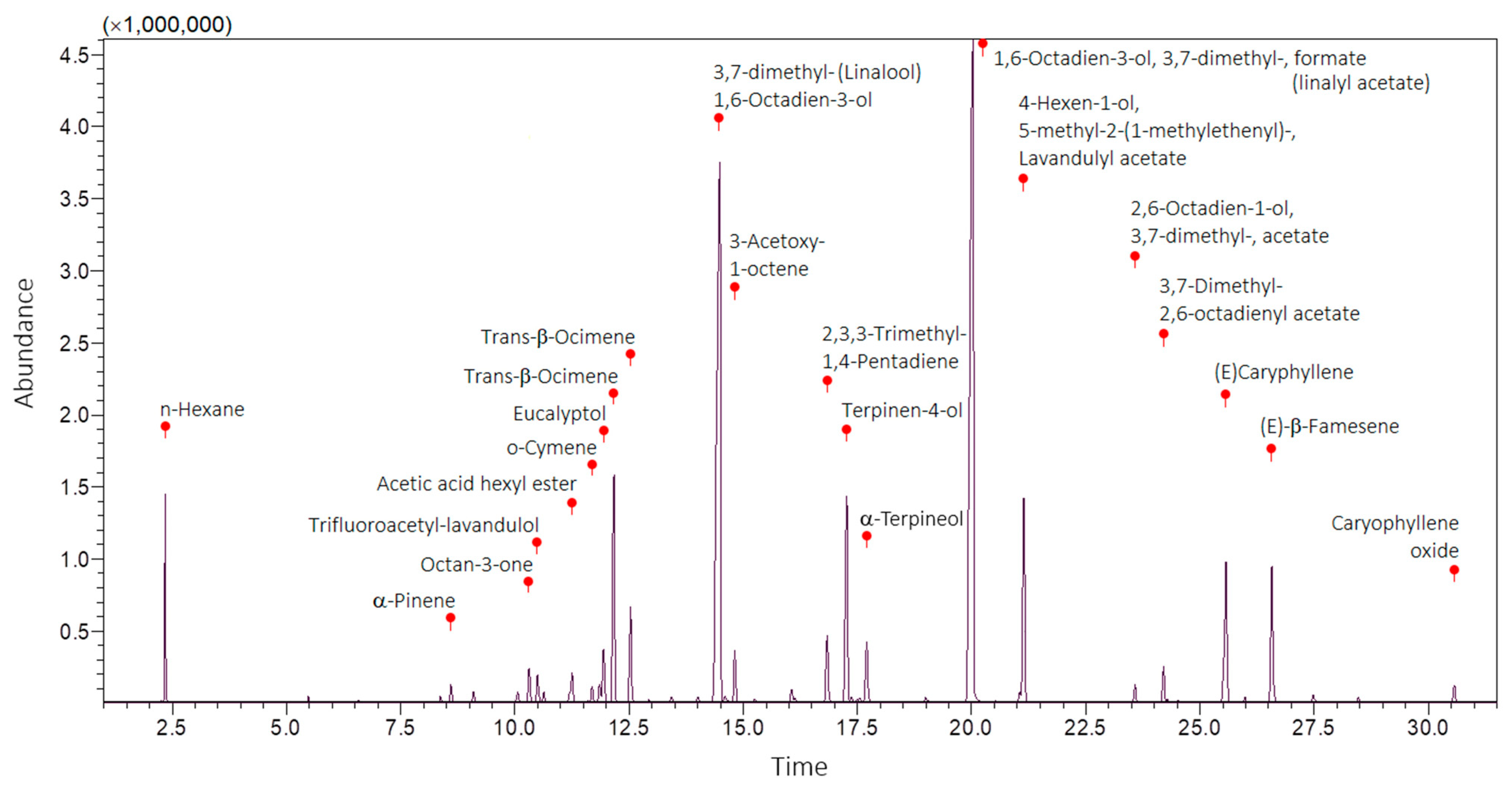

2.1. GC–MS of LaEO

2.2. Antifungal Susceptibility of LaEO

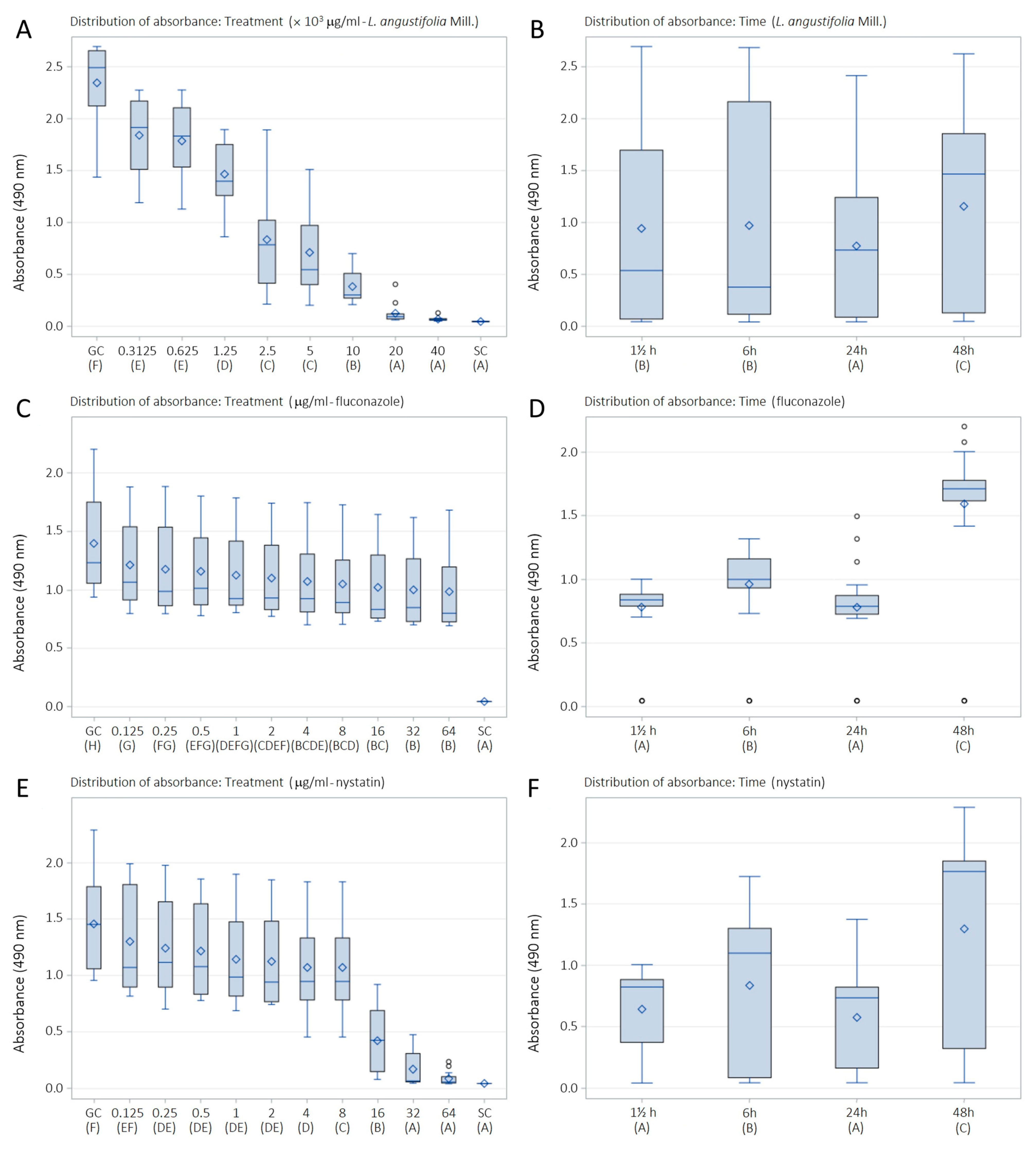

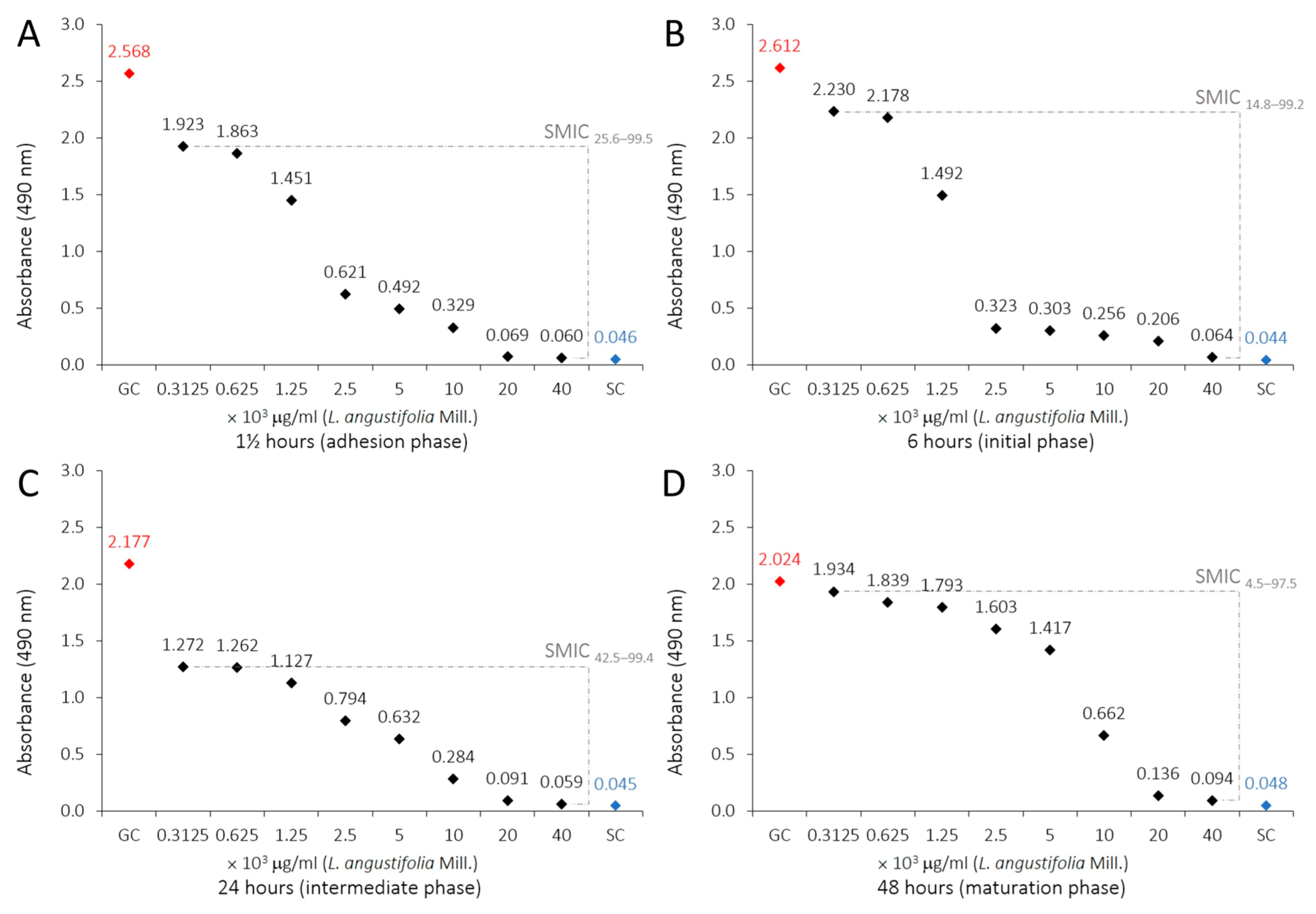

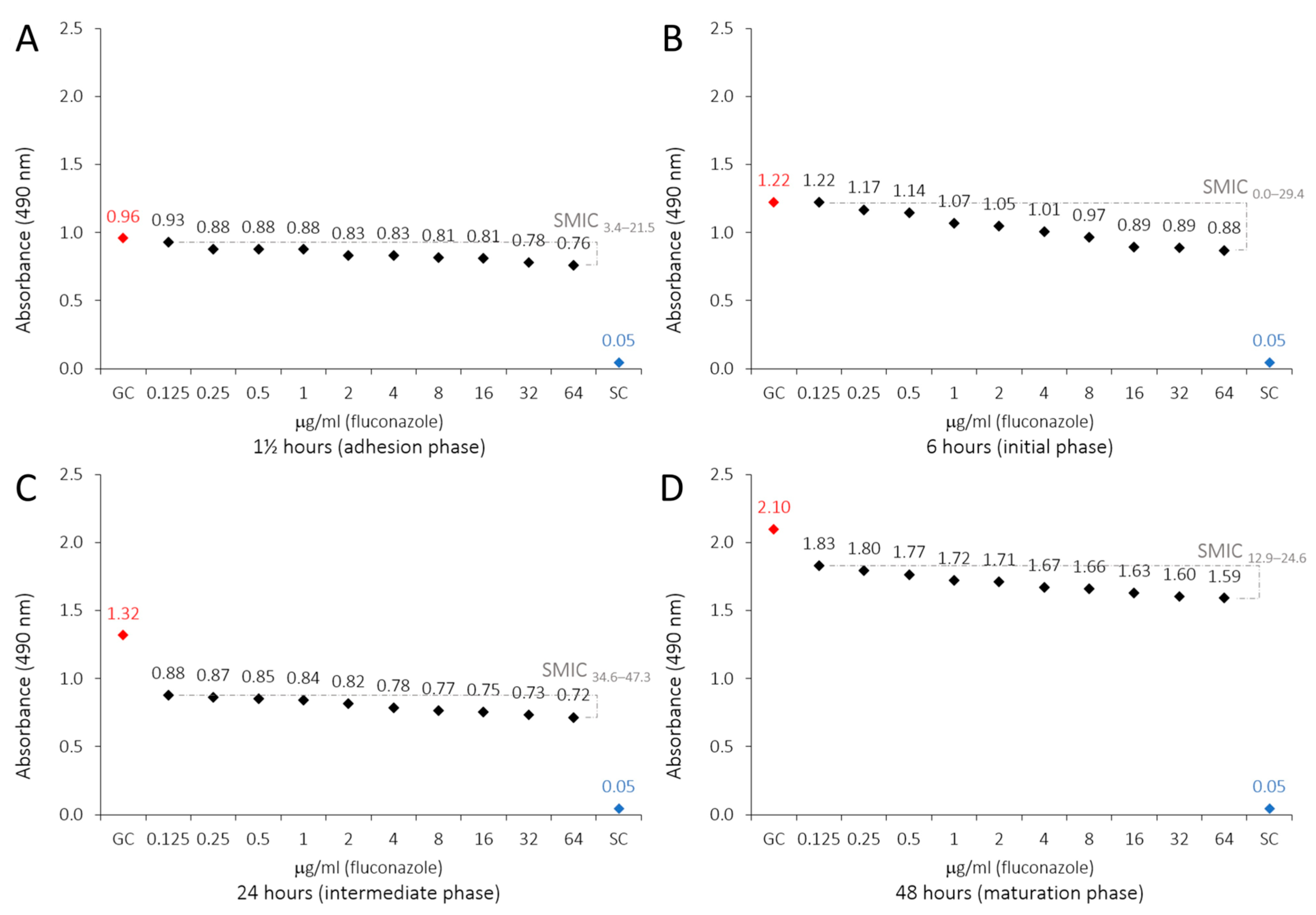

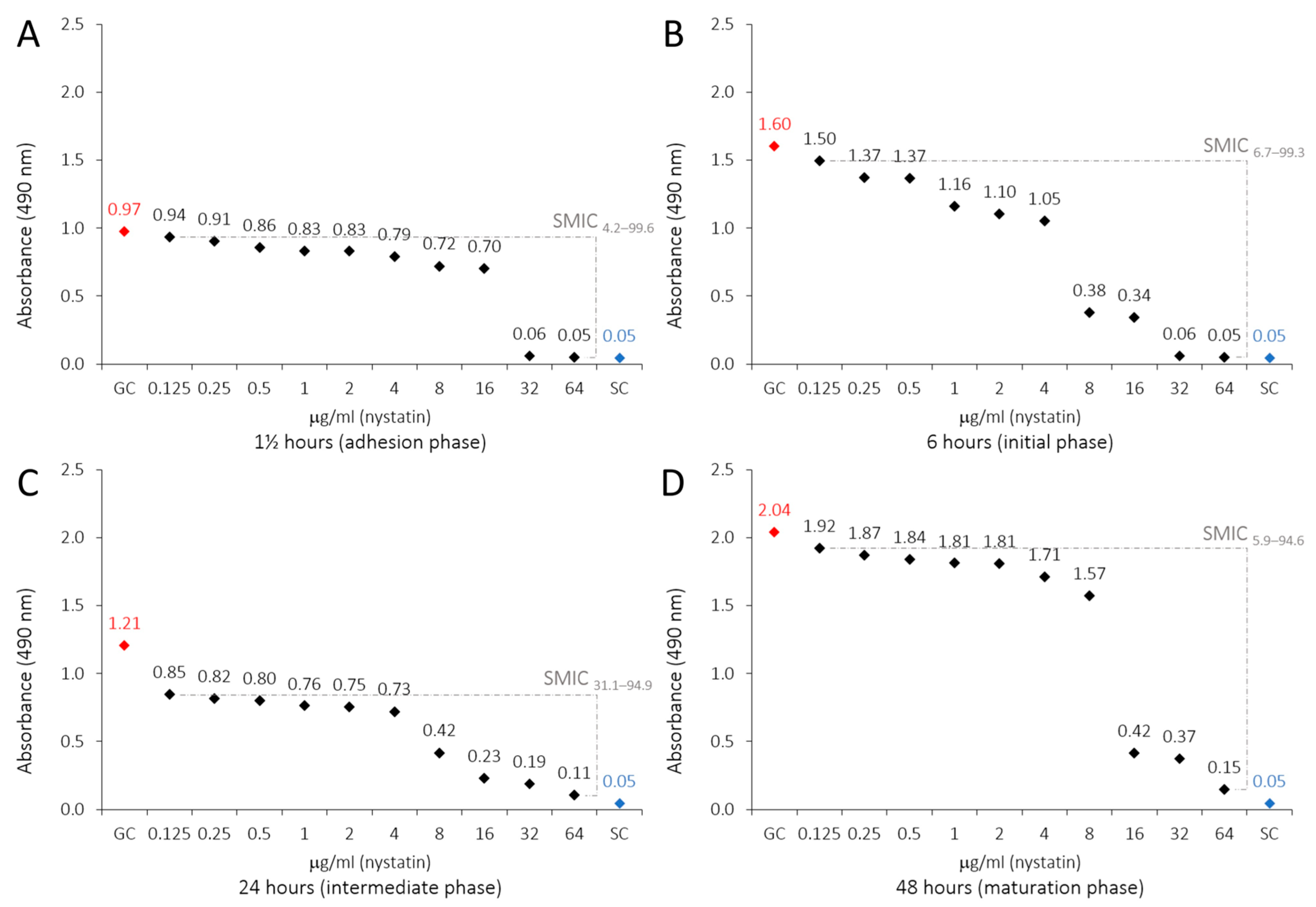

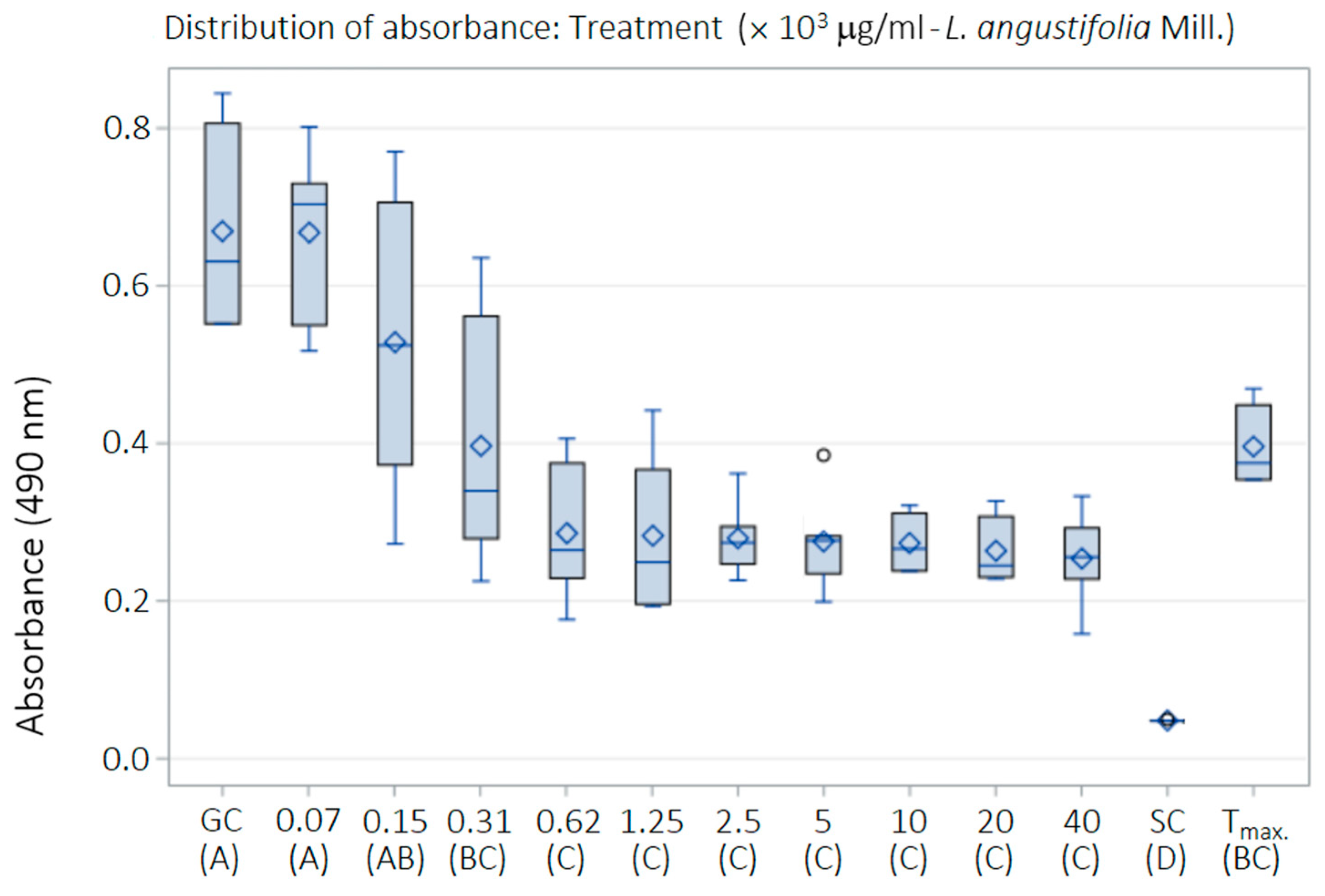

2.3. Antibiofilm Susceptibility of LaEO

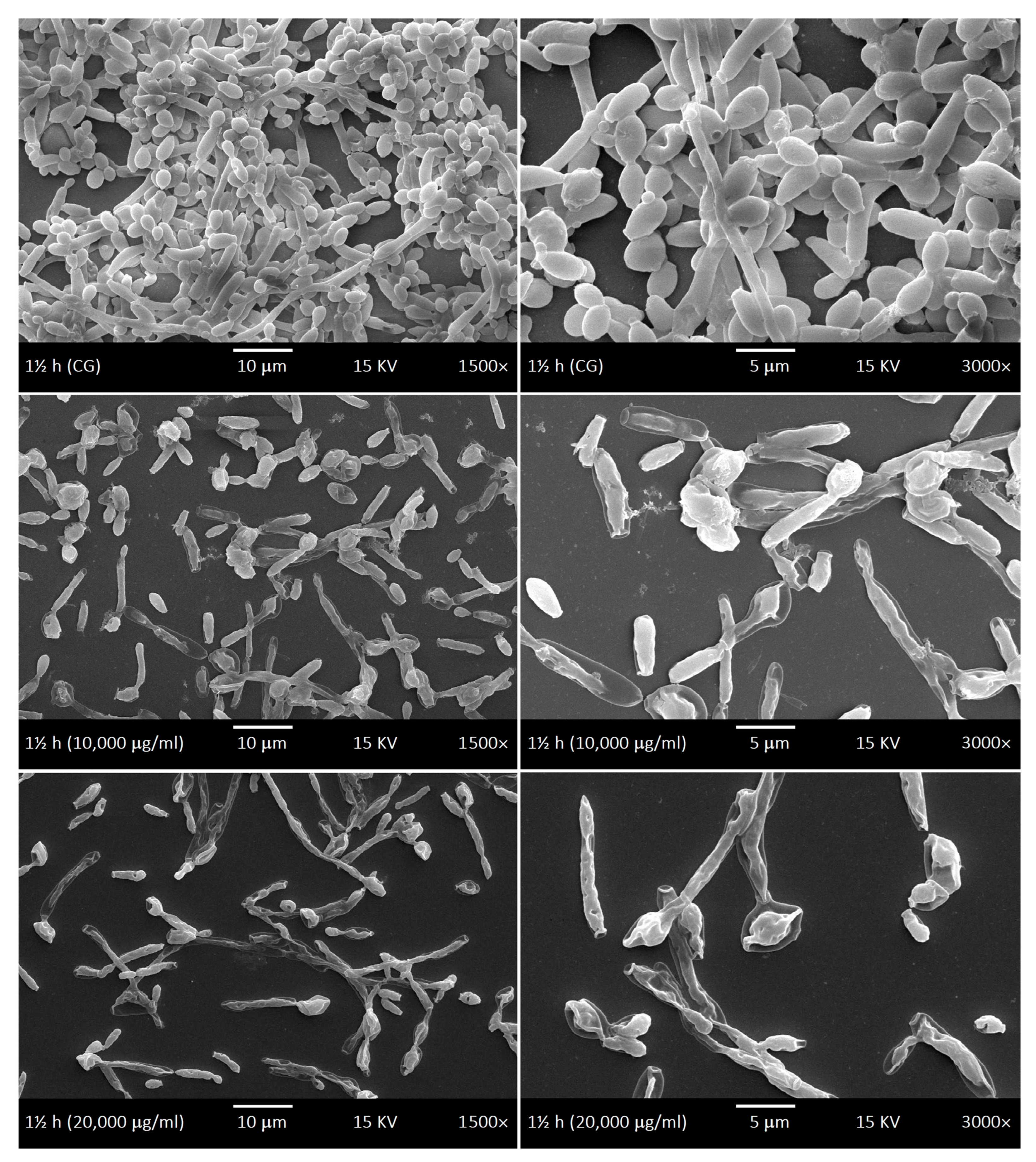

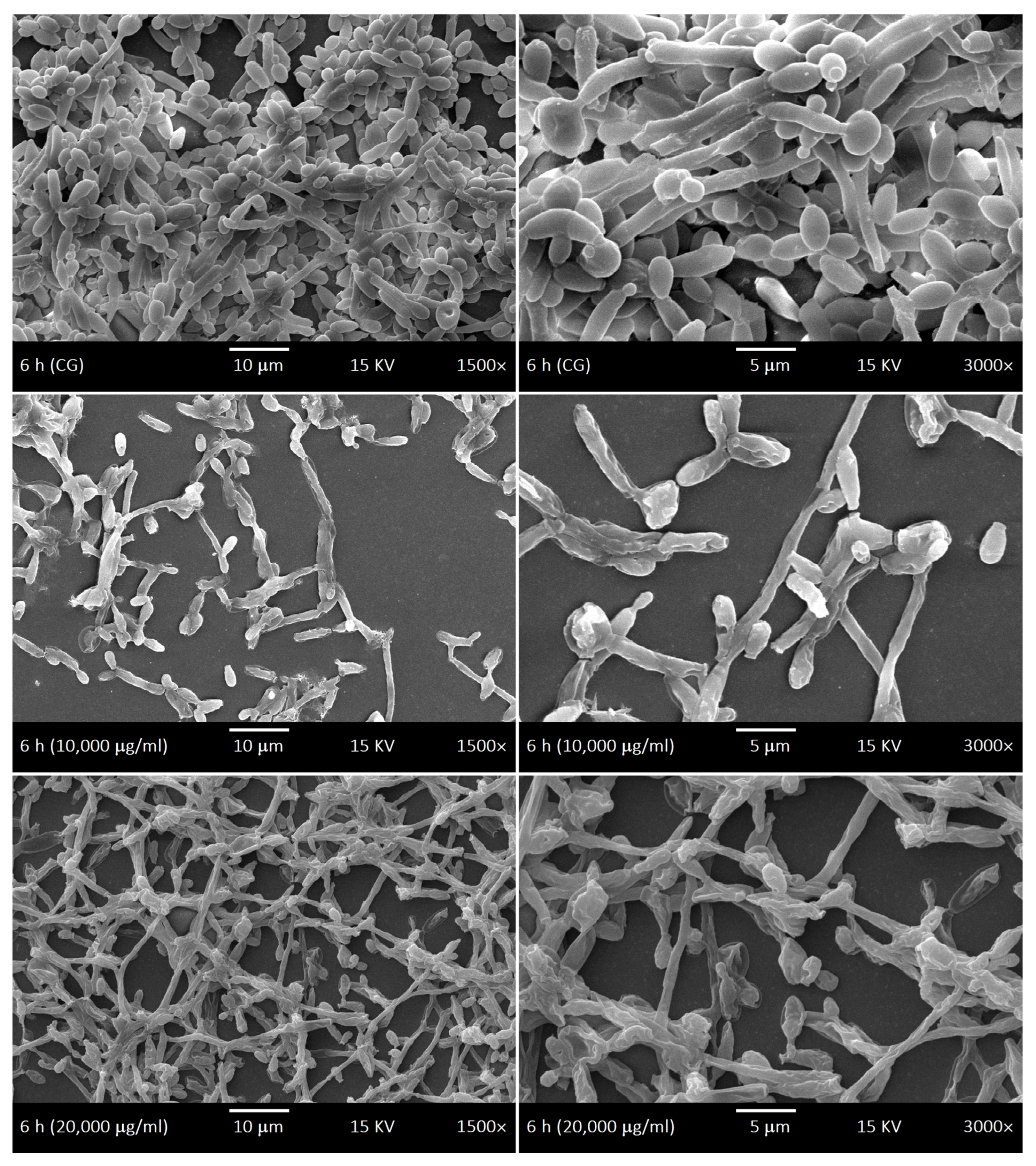

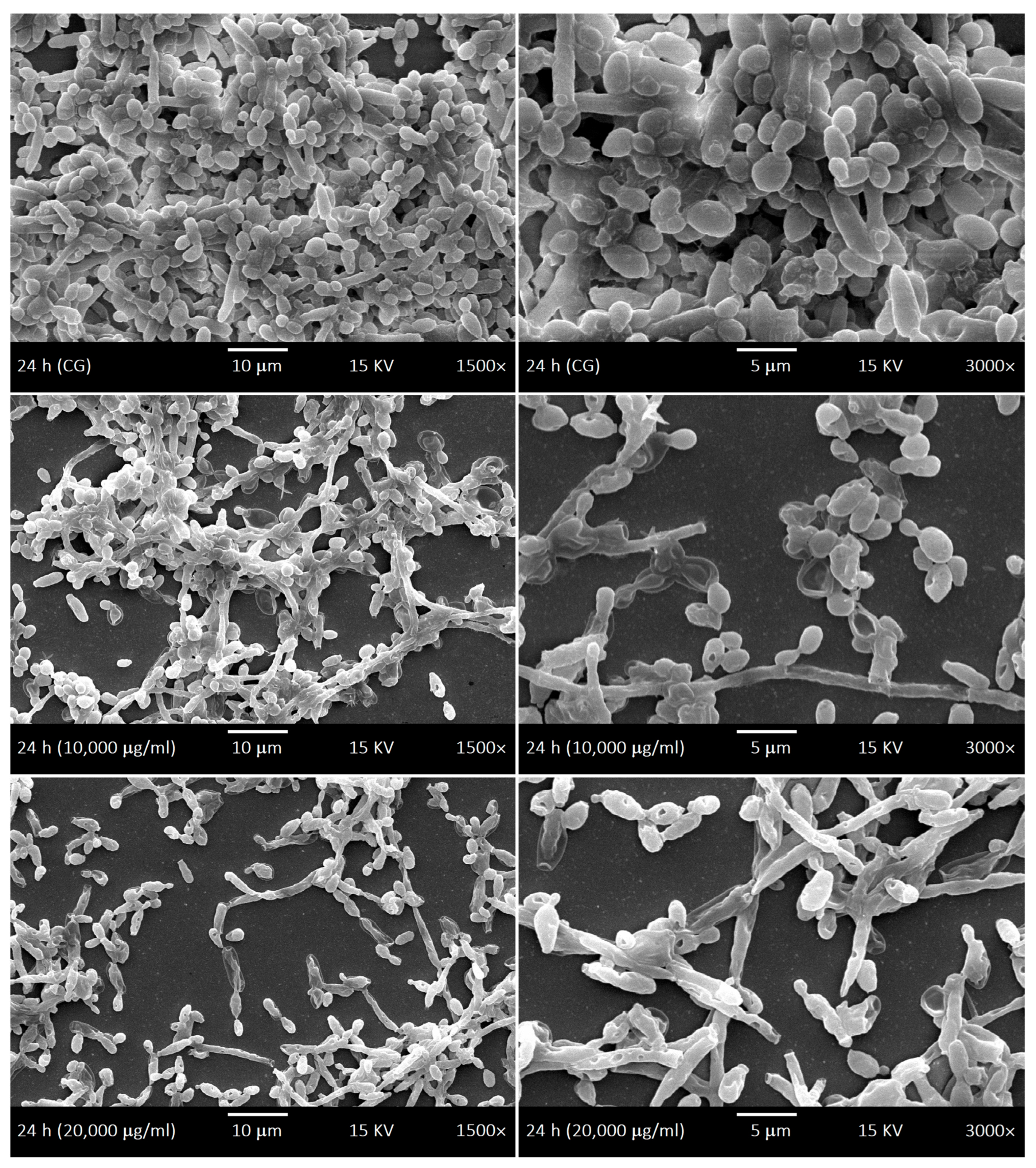

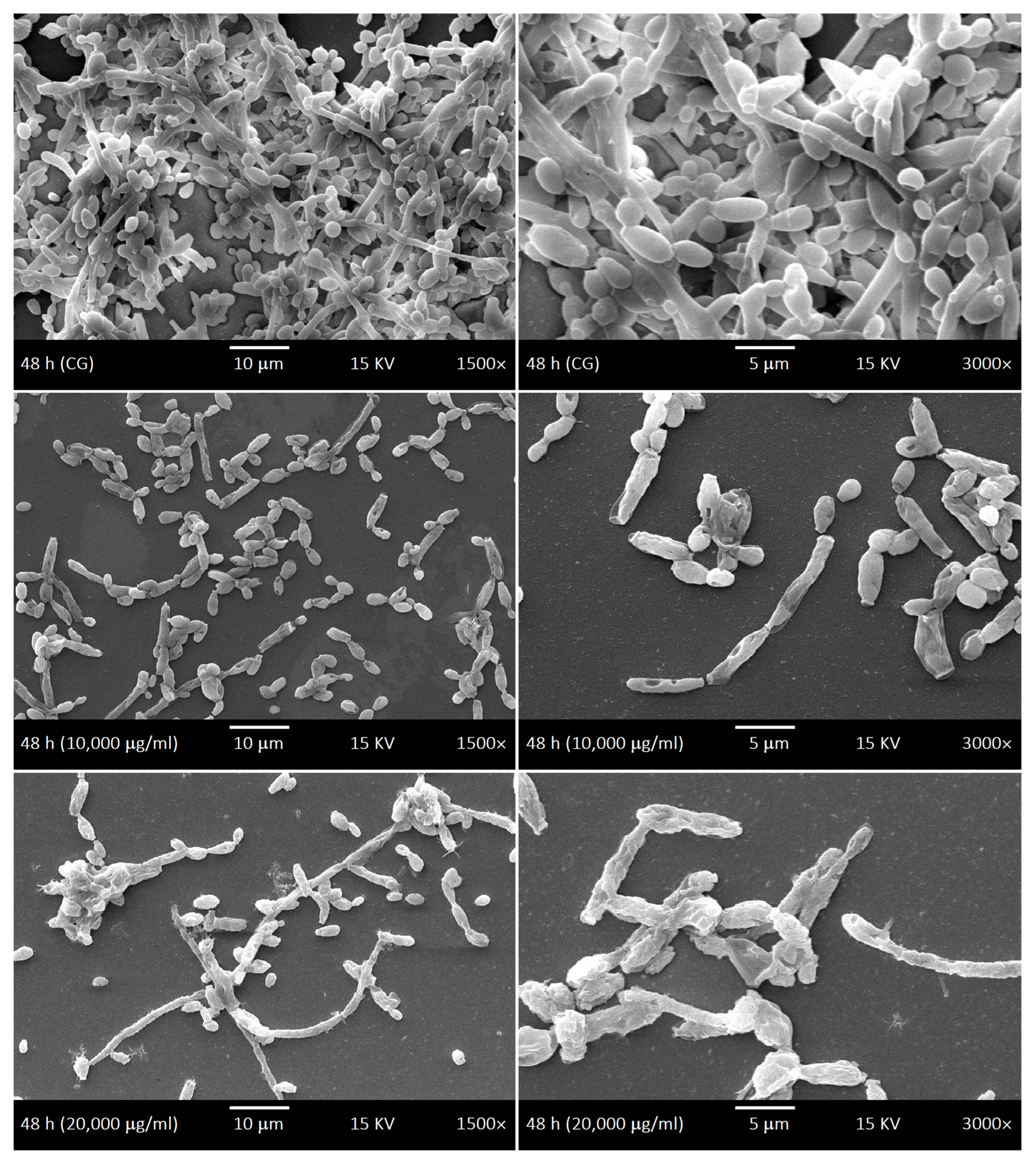

2.4. SEM of Biofilms and LaEO

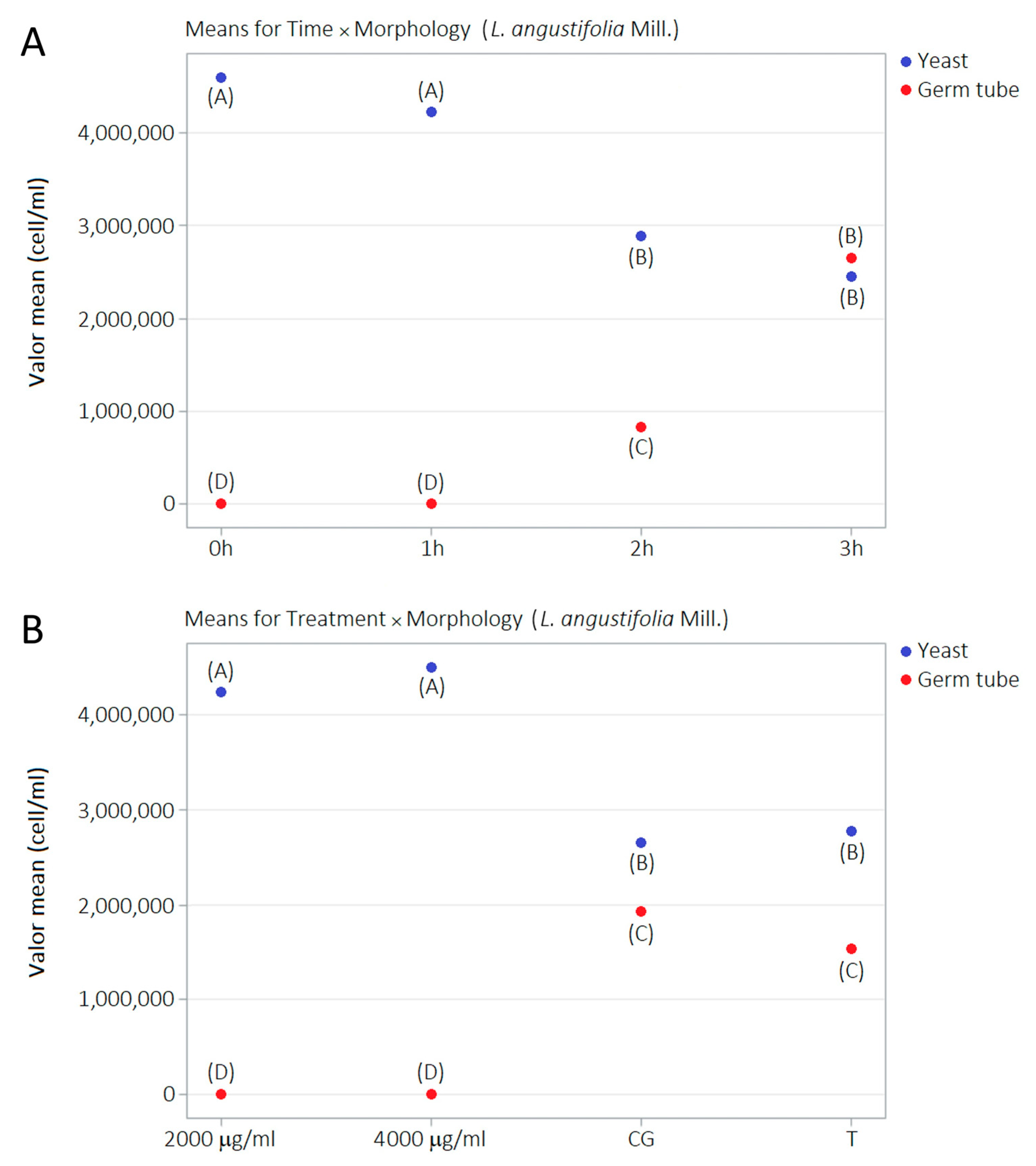

2.5. Germ Tube Development Kinetics and LaEO

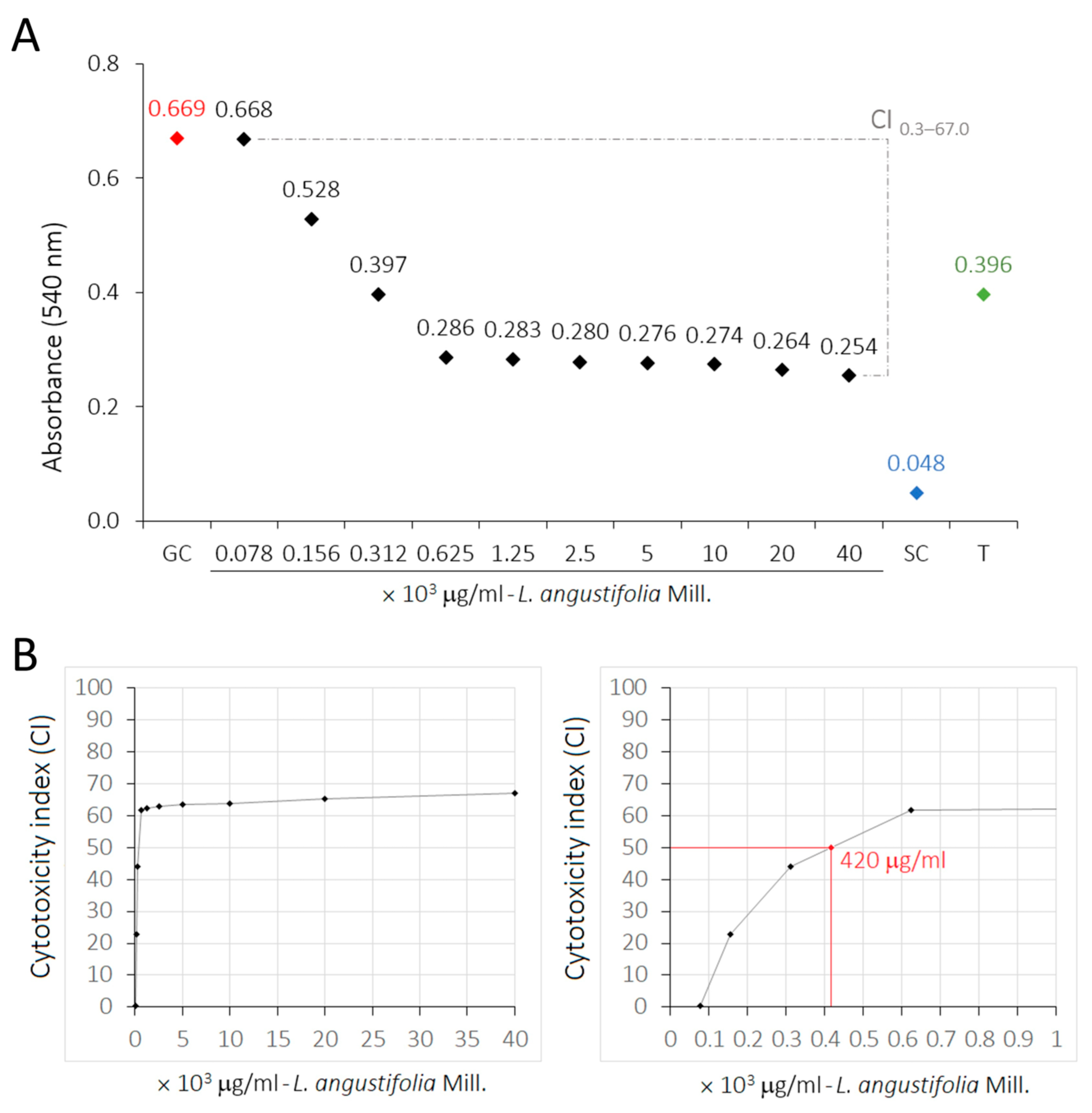

2.6. Cytotoxicity of LaEO

2.7. Selectivity Index of LaEO

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Essential Oil Source

4.2. GC–MS Analysis

4.3. Yeasts and Growth Conditions

4.4. Antifungal Susceptibility Tests

4.5. Minimum Fungicidal Concentration

4.6. Antibiofilm Tests

4.6.1. Culture of Planktonic Yeasts

4.6.2. Adsorb Films

4.6.3. Biofilm Control

4.6.4. Treatment Groups of Biofilms

4.6.5. Bioactivity Analysis

4.7. Ultrastructural Morphology of Biofilms

4.8. Germ Tube Induction Assays

4.8.1. Yeast Culture

4.8.2. Treatment Throughout Germ Tube Development Kinetics

4.9. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Tests

4.9.1. Cell Culture

4.9.2. Sulforhodamine B Assay

4.10. Selectivity Index

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AB | Amphotericin B |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Units |

| CI50 | Cytotoxicity Index 50 |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| FLU | Fluconazole |

| GC–MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| HaCaT | Human Adult Low Calcium High Temperature Keratinocytes |

| LaEO | Lavandula angustifolia Essential Oil |

| LRI | Linear Retention Index |

| MFC | Minimum Fungicidal Concentration |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MIC50 | Inhibitory Concentration for 50% Reduction |

| MOPS | 3-(N-Morpholino)propanesulfonic Acid |

| NYS | Nystatin |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| QC | Quality Control |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute Medium |

| SDA | Sabouraud Dextrose Agar |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SI | Selectivity Index |

| SMIC | Sessile Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| SMIC50 | Sessile Inhibitory Concentration for 50% Reduction |

| SRB | Sulforhodamine B |

| TIC | Total Ion Chromatogram |

| TTZ | Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| XTT | 2,3-Bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulphophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium Hydroxide |

| YEPD | Yeast Extract Peptone Dextrose |

| YNB | Yeast Nitrogen Base |

References

- Diaz, P.I.; Dongari-Bagtzoglou, A. Critically Appraising the Significance of the Oral Mycobiome. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunetel, L.; Tamanai-Shacoori, Z.; Martin, B.; Autier, B.; Guiller, A.; Bonnaure-Mallet, M. Interactions between oral commensal Candida and oral bacterial communities in immunocompromised and healthy children. J. Mycol. Méd. 2019, 29, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, V.K.; Lee, T.Y.; Rusliza, B.; Chong, P.P. Dissecting Candida albicans infection from the perspective of C. albicans virulence and omics approaches on host–pathogen interaction: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, M.C.B.; Ferreira Dalla Pria, H.R.; Truong, M.T.; Shroff, G.S.; Marom, E.M. Invasive Fungal Pneumonia in Immunocompromised Patients. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 60, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichard, D.C.; Freeman, A.F.; Cowen, E.W. Primary immunodeficiency update: Part II. Syndromes associated with mucocutaneous candidiasis and noninfectious cutaneous manifestations. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 73, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardi, J.C.O.; Scorzoni, L.; Bernardi, T.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Mendes Giannini, M.J.S. Candida species: Current epidemiology, pathogenicity, biofilm formation, natural antifungal products and new therapeutic options. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013, 62, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatasalu, M.R.; Murang, Z.R.; Ramasamy, D.T.R.; Dhaliwal, J.S. Oral health problems among palliative and terminally ill patients: An integrated systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motaung, T.E.; Ells, R.; Pohl, C.H.; Albertyn, J.; Tsilo, T.J. Genome-wide functional analysis in Candida albicans. Virulence 2017, 8, 1563–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucci, M.; Barreiros, G.; Guimarães, L.F.; Deriquehem, V.A.S.; Castiñeiras, A.C.; Nouér, S.A. Increased incidence of candidemia in a tertiary care hospital with the COVID-19 pandemic. Mycoses 2021, 64, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, G.; Saville, S.P.; Thomas, D.P.; López-Ribot, J.L. Candida biofilms: An update. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.J.D.; Silva, T.A.D.; Almeida, H.; Rodrigues Netto, M.F.; Cerdeira, C.D.; Höfling, J.F.; Boriollo, M.F.G. Candida species biotypes in the oral cavity of infants and children with orofacial clefts under surgical rehabilitation. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 124, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Lara, M.F.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L. Invasive Candidiasis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quindós, G. Epidemiology of candidaemia and invasive candidiasis. A changing face. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2014, 31, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues Netto, M.F.; Júnior da Silva, J.; Andrielle da Silva, T.; Oliveira, M.C.; Höfling, J.F.; de Andrade Bressan, E.; Vargas de Oliveira Figueira, A.; Gomes Boriollo, M.F. DNA microsatellite genotyping of potentially pathogenic Candida albicans and C. dubliniensis isolated from the oral cavity and dental prostheses. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 149, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaci, O.; Haliki-Uztan, A.; Ozturk, B.; Toksavul, S.; Ulusoy, M.; Boyacioglu, H. Determining Candida spp. Incidence in Denture Wearers. Mycopathologia 2010, 169, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.Y.; Meurman, J.H.; Kari, K.; Rautemaa, R.; Samaranayake, L.P. In vitro adhesion of Candida species to denture base materials. Mycoses 2006, 49, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C.B.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Fortes, C.V.; Bueno, F.L.; de Wever, B.; Oliveira, V.C.; Macedo, A.P.; Paranhos, H.F.O.; da Silva, C.H.L. Effect of local hygiene protocols on denture-related stomatitis, biofilm, microbial load, and odor: A randomized controlled trial. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, A.; Coco, B.J.; Milligan, S.; Young, B.; Lappin, D.F.; Bagg, J.; Murray, C.; Ramage, G. Reducing the Incidence of Denture Stomatitis: Are Denture Cleansers Sufficient? J. Prosthodont. 2010, 19, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulak, Y.; Arikan, A.; Delibalta, N. Comparison of three different treatment methods for generalized denture stomatitis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1994, 72, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taff, H.T.; Mitchell, K.F.; Edward, J.A.; Andes, D.R. Mechanisms of Candida biofilm drug resistance. Future Microbiol. 2013, 8, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekor, M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 4, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wińska, K.; Mączka, W.; Łyczko, J.; Grabarczyk, M.; Czubaszek, A.; Szumny, A. Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Agents-Myth or Real Alternative? Molecules 2019, 24, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, R.R. Medicinally potential plants of Labiatae (Lamiaceae) family: An overview. Res. J. Med. Plant. 2012, 6, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažeković, B.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Kindl, M.; Pepeljnjak, S.; Vladimir-Knežević, S. Chemical composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of essential oils of Lavandula × intermedia ‘Budrovka’ and L. angustifolia cultivated in Croatia. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 123, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprari, C.; Fantasma, F.; Divino, F.; Bucci, A.; Iorizzi, M.; Naclerio, G.; Ranalli, G.; Saviano, G. Chemical profile, in vitro biological activity and comparison of essential oils from fresh and dried flowers of Lavandula angustifolia L. Molecules 2021, 26, 5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobros, N.; Zawada, K.D.; Paradowska, K. Phytochemical Profiling, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Plants Belonging to the Lavandula Genus. Molecules 2022, 28, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smigielski, K.; Prusinowska, R.; Stobiecka, A.; Kunicka-Styczyñska, A.; Gruska, R. Biological Properties and Chemical Composition of Essential Oils from Flowers and Aerial Parts of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia). J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2018, 21, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, E.R.L.d.; Cruz, J.H.d.A.; Gomes, N.M.L.; Ramos, L.L.; Oliveira Filho, A.A.d. Lavandula angustifolia Miller e sua utilização na Odontologia: Uma breve revisão. Arch. Health Investig. 2019, 7, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benomari, F.Z.; Sarazin, M.; Chaib, D.; Pichette, A.; Boumghar, H.; Boumghar, Y.; Djabou, N. Chemical Variability and Chemotype Concept of Essential Oils from Algerian Wild Plants. Molecules 2023, 28, 4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Foppa, I.; Liebowitz, R.; Nelson, J.; Smith, M.; Sollars, D.; Ulbricht, C. Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Miller). J. Herb. Pharmacother. 2004, 4, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Auria, F.D.; Tecca, M.; Strippoli, V.; Salvatore, G.; Battinelli, L.; Mazzanti, G. Antifungal activity of Lavandula angustifolia essential oil against Candida albicans yeast and mycelial form. Med. Mycol. 2005, 43, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rapper, S.; Viljoen, A.; van Vuuren, S. The In Vitro Antimicrobial Effects of Lavandula angustifolia Essential Oil in Combination with Conventional Antimicrobial Agents. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 2752739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preethi, G.; Devi, R.G.; Priya, A.J. Knowledge, Attitude and Awareness towards Benefits of Lavender Oil. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2020, 32, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B.; Williams, C.A. Phytochemistry of the genus Lavandula. In Lavender: The Genus Lavandula; Lis-Balchin, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; pp. 86–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lesage-Meessen, L.; Bou, M.; Sigoillot, J.C.; Faulds, C.B.; Lomascolo, A. Essential oils and distilled straws of lavender and lavandin: Current uses and potential applications in white biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 3375–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriti, M.; Colnaghi, G.; Chemat, F.; Smadja, J.; Faoro, F.; Visinoni, F.A. Histocytochemistry and scanning electron microscopy of lavender glandular trichomes following conventional and microwave-assisted hydrodistillation: A comparative study. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis-Balchin, M. (Ed.) Lavender: The Genus Lavandula; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; 296p, ISBN 978-0415284868. [Google Scholar]

- Shafaghat, A.; Salimi, F.; Amani-Hooshyar, V. Phytochemical and antimicrobial activities of Lavandula officinalis leaves and stems. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woronuk, G.; Demissie, Z.; Rheault, M.; Mahmoud, S. Biosynthesis and therapeutic properties of Lavandula essential oil constituents. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angioni, A.; Barra, A.; Coroneo, V.; Dessi, S.; Cabras, P. Chemical composition, seasonal variability, and antifungal activity of Lavandula stoechas L. ssp. stoechas essential oils from stems/leaves and flowers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4364–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, E.J.; Griffiths, D.M.; Quirk, L.; Brownrigg, A.; Croot, K. Effects of essential oils and touch on resistance to nursing care procedures and dementia-related behaviours in a residential care facility. Int. J. Aromather. 2002, 12, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, H.M.; Wilkinson, J.M. Biological activities of lavender essential oil. Phytother. Res. 2002, 16, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.J.; Kemper, K.J. Lavender (Lavandula spp.); Longwood Herbal Task Force & Center for Holistic Pediatric Education and Research: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; 32p. [Google Scholar]

- Field, T.; Field, T.; Cullen, C.; Largie, S.; Diego, M.; Schanberg, S.; Kuhn, C. Lavender bath oil reduces stress and crying and enhances sleep in very young infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2008, 84, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Kim, H.; Lao, R.P. An olfactory stimulus modifies nighttime sleep in young men and women. Chronobiol. Int. 2005, 22, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höferl, M.; Krist, S.; Buchbauer, G. Chirality influences the effects of linalool on physiological stress parameters. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 1188–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.; Hopkins, V.; Hensford, C.; MacLaughlin, V.; Wilkinson, D.; Rosenvinge, H. Lavender oil as a treatment for agitated behaviour in severe dementia: A placebo-controlled study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2002, 17, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R. The value of lavender for rest and activity in elderly patients. Complement. Ther. Med. 1996, 4, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritsidima, M.; Newton, T.; Asimakopoulou, K. The effects of lavender scent on dental patient anxiety: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2010, 38, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis-Balchin, M.; Hart, S. Studies on the mode of action of the essential oil of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia P. Miller). Phytother. Res. 1999, 13, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.; Cavanagh, H.M.A.; Wilkinson, J.M. Antifungal activity of Australian grown Lavandula spp. essential oils against Aspergillus nidulans, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Leptosphaeria maculans and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2007, 19, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, J.; Brown, R.; Coulter, F.; Irvine, E.; Copland, C. Aromatherapy and behaviour disturbances in dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2001, 16, 1010–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, Y.; Hara, C.; Tamura, K.; Fujii, T.; Nakamura, K.; Masujima, T.; Aoki, T. Sedative effect on humans of inhalation of essential oil of linalool: Sensory evaluation and physiological measurements using optically active linalools. Anal. Chim. Acta 1998, 365, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasev, T.; Toléva, P.; Balabanova, V. Effet neuro-psychique des huiles essentielles bulgares de rose, de lavande et de géranium. Folia Med. 1969, 11, 307–317. [Google Scholar]

- Tisserand, R. The Essential Oil Safety Data Manual; Tisserand Aromatherapy Institute: Brighton, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils—A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, C.I.S.; Sousa, M.N.A.; Filho, G.G.A.; Freitas, F.O.R.; Uchoa, D.P.L.; Nobre, M.S.C.; Bezerra, A.L.D.; Rolim, L.A.D.M.M.; Morais, A.M.B.; Nogueira, T.B.S.S.; et al. Antifungal activity of linalool against fluconazole-resistant clinical strains of vulvovaginal Candida albicans and its predictive mechanism of action. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2022, 55, e11831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; Coppola, R.; De Feo, V. Essential oils and antifungal activity. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts: Approved Standard-Third Edition. In CLSI Document M27-A3; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Method for Antifungal Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts: Approved Guideline-Second Edition. In CLSI Document M44-A2; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Fourth Informational Supplement. In CLSI Document M27-S4; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bassi, R.C.; Boriollo, M.F.G. Amphotericin B, fluconazole, and nystatin as development inhibitors of Candida albicans biofilms on a dental prosthesis reline material: Analytical models in vitro. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Das, J.; Foley, I. Biofilm susceptibility to antimicrobials. Adv. Dent. Res. 1997, 11, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouidhi, B.; Al Qurashi, Y.M.; Chaieb, K. Drug resistance of bacterial dental biofilm and the potential use of natural compounds as alternative for prevention and treatment. Microb. Pathog. 2015, 80, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrabiah, M.; Alshagroud, R.S.; Alsahhaf, A.; Almojaly, S.A.; Abduljabbar, T.; Javed, F. Presence of Candida species in the subgingival oral biofilm of patients with peri-implantitis. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranno, N.; Cristalli, M.P.; Mengoni, F.; Sauzullo, I.; Annibali, S.; Polimeni, A.; La Monaca, G. Comparison of the effects of air-powder abrasion, chemical decontamination, or their combination in open-flap surface decontamination of implants failed for peri-implantitis: An ex vivo study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.C.; Lu, J.J.; Chang, S.C.; Ge, M.C. Identification of microbiota in peri-implantitis pockets by MALDI-TOF MS. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcanti, Y.W.; Wilson, M.; Lewis, M.; Del-Bel-Cury, A.A.; da Silva, W.J.; Williams, D.W. Modulation of Candida albicans virulence by bacterial biofilms on titanium surfaces. Biofouling 2016, 32, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, Y.W.; Wilson, M.; Lewis, M.; Williams, D.; Senna, P.M.; Del-Bel-Cury, A.A.; da Silva, W.J. Salivary pellicles equalise surfaces’ charges and modulate the virulence of Candida albicans biofilm. Arch. Oral Biol. 2016, 66, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.G.S.; Costa, R.C.; Sampaio, A.A.; Abdo, V.L.; Nagay, B.E.; Castro, N.; Retamal-Valdes, B.; Shibli, J.A.; Feres, M.; Barão, V.A.R.; et al. Cross-kingdom microbial interactions in dental implant-related infections: Is Candida albicans a new villain? iScience 2022, 25, 103994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, W.L.C.; Boriollo, M.F.G.; Tonon, C.C.; da Silva, J.J.; Oliveira, M.C.; de Moraes, F.C.; Spolidorio, D.M.P. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Syzygium cumini leaves and their potential effects on odontogenic pathogens and biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 995521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklenár, Z.; Scigel, V.; Horácková, K.; Slanar, O. Compounded preparations with nystatin for oral and oromucosal administration. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2013, 70, 759–762. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, W.-H.; Lai, K.-S.; Lim, S.-H.E. Combination therapy involving Lavandula angustifolia and its derivatives in exhibiting antimicrobial properties and combatting antimicrobial resistance: Current challenges and future prospects. Processes 2021, 9, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijatovic, S.; Stankovic, J.A.; Calovski, I.C.; Dubljanin, E.; Pljevljakusic, D.; Bigovic, D.; Dzamic, A. Antifungal activity of Lavandula angustifolia essential oil against Candida albicans: Time-kill study on pediatric sputum isolates. Molecules 2022, 27, 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behmanesh, F.; Pasha, H.; Sefidgar, A.A.; Taghizadeh, M.; Moghadamnia, A.A.; Adib Rad, H.; Shirkhani, L. Antifungal effect of lavender essential oil (Lavandula angustifolia) and clotrimazole on Candida albicans: An in vitro study. Scientifica 2015, 2015, 261397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, M.A.; Bungau, S.; Tit, D.M.; Zaha, D.C.; Nechifor, A.C.; Behl, T.; Chambre, D.; Lupitu, A.I.; Copolovici, L.; Copolovici, D.M. Chemical profile, antioxidant capacity, and antimicrobial activity of essential oils extracted from three different varieties (Moldoveanca 4, Vis Magic 10, and Alba 7) of Lavandula angustifolia. Molecules 2021, 26, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alteriis, E.; Maione, A.; Falanga, A.; Bellavita, R.; Galdiero, S.; Albarano, L.; Salvatore, M.M.; Galdiero, E.; Guida, M. Activity of free and liposome-encapsulated essential oil from Lavandula angustifolia against persister-derived biofilm of Candida auris. Antibiotics 2021, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Bamunuarachchi, N.I.; Tabassum, N.; Jo, D.M.; Khan, M.M.; Kim, Y.M. Suppression of hyphal formation and virulence of Candida albicans by natural and synthetic compounds. Biofouling 2021, 37, 626–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornitzer, D. Regulation of Candida albicans hyphal morphogenesis by endogenous signals. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Ferreira, S.; Duarte, A.; Mendonça, D.I.; Domingues, F.C. Antifungal activity of Coriandrum sativum essential oil, its mode of action against Candida species and potential synergism with amphotericin B. Phytomedicine 2011, 19, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronchin, G.; Bouchara, J.P.; Annaix, V.; Robert, R.; Senet, J.M. Fungal cell adhesion molecules in Candida albicans. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1991, 7, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, A.; Locke, I.C.; Evans, C.S. Cytotoxicity of lavender oil and its major components to human skin cells. Cell Prolif. 2004, 37, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boriollo, M.F.G.; Marques, M.B.; da Silva, T.A.; da Silva, J.J.; Dias, R.A.; Silva Filho, T.H.N.; Melo, I.L.R.; Dos Santos Dias, C.T.; Bernardo, W.L.C.; de Mello Silva Oliveira, N.; et al. Antimicrobial potential, phytochemical profile, cytotoxic and genotoxic screening of Sedum praealtum A. DC. (balsam). BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Bernardo, W.L.; Boriollo, M.F.G.; Tonon, C.C.; da Silva, J.J.; Cruz, F.M.; Martins, A.L.; Höfling, J.F.; Spolidorio, D.M.P. Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles and extracts of Syzygium cumini flowers and seeds: Periodontal, cariogenic and opportunistic pathogens. Arch. Oral Biol. 2021, 125, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantón, E.; Pemán, J.; Viudes, A.; Quindós, G.; Gobernado, M.; Espinel-Ingroff, A. Minimum fungicidal concentrations of amphotericin B for bloodstream Candida species. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2003, 45, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullo, F.P.; Sardi, J.C.O.; Santos, V.A.F.F.M.; Sangalli-Leite, F.; Pitangui, N.S.; Rossi, S.A.; Paula E Silva, A.C.A.d.; Soares, L.A.; Silva, J.F.; Oliveira, H.C.; et al. Antifungal activity of maytenin and pristimerin. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 340787. [Google Scholar]

- Regasini, L.O.; Pivatto, M.; Scorzoni, L.; Benaducci, T.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Giannini, M.J.S.M.; Barreiro, E.J.; Siva, D.H.S.; Bolzani, V.D.S. Antimicrobial activity of Pterogyne nitens Tul., Fabaceae, against opportunistic fungi. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2010, 20, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, J.; Kuhn, D.M.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Hoyer, L.L.; McCormick, T.; Ghannoum, M.A. Biofilm formation by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans: Development, architecture, and drug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 5385–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, J.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Ghannoum, M.A. In vitro growth and analysis of Candida biofilms. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1909–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yan, Z.; Xu, J. Quantitative variation of biofilms among strains in natural populations of Candida albicans. Microbiology 2003, 149, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, C.; Crow, S.A.; Ahearn, D.G. Adherence of Candida albicans to silicone induces immediate enhanced tolerance to fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3358–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, C.G.; Uppuluri, P.; Tristan, A.R.; Wormley, F.L.; Mowat, E.; Ramage, G.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1494–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, G.; vande Walle, K.; Wickes, B.L.; López-Ribot, J.L. Standardized method for in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 2475–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, I.; Felipe Rodrigues, M.P.; Bacelli, G.K.; Munin, E.; Alves, L.P.; Costa, M.S. Aloe vera extract reduces both growth and germ tube formation by Candida albicans. Mycoses 2012, 55, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.K.; Johnson, E.M.; Warnock, D.W. Identification of Pathogenic Fungi; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, K.A.; Carson, C.F.; Riley, T.V. Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil inhibits germ tube formation by Candida albicans. Med. Mycol. 2000, 38, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukamp, P.; Petrussevska, R.T.; Breitkreutz, D.; Hornung, J.; Markham, A.; Fusenig, N.E. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 106, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adan, A.; Kiraz, Y.; Baran, Y. Cell proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2016, 17, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, G.C.; de Feiria, S.N.B.; Santana, P.L.; Anibal, P.C.; Boriollo, M.F.G.; Buso-Ramos, M.M.; Barbosa, J.P.; de Oliveira, T.R.; Hofling, J.F. Antifungal and cytotoxic activity of purified biocomponents as carvone, menthone, menthofuran and pulegone from Mentha spp. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2016, 10, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, Ł.; Bednarz-Misa, I.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Kubiak, A.; Kasprzyk, P.; Sozański, T.; Przybylska, D.; Piórecki, N.; Krzystek-Korpacka, M. Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas L.) extracts exert cytotoxicity in melanoma cell lines: A factorial time-dependent analysis using SRB and MTT assays. Molecules 2022, 27, 4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yang, W.; Li, Z.; Jia, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Xiao, T. Bitter apricot essential oil induces apoptosis in human HaCaT keratinocytes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 34, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skehan, P.; Storeng, R.; Scudiero, D.; Monks, A.; McMahon, J.; Vistica, D.; Warren, J.T.; Bokesch, H.; Kenney, S.; Boyd, M.R. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer drug screening. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990, 82, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrol, D.H.; Chassagne, F.; Dettweiler, M.; Quave, C.L. Antibacterial activity of plant species used for oral health against Porphyromonas gingivalis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, P.Y.; Milton, M.N. The determination and interpretation of the therapeutic index in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterman, C.; Calcul, L.; Beau, J.; Ma, W.S.; Lebar, M.D.; von Salm, J.L.; Harter, C.; Mutka, T.; Morton, L.C.; Maignan, P.; et al. Miniaturized cultivation of microbiota for antimalarial drug discovery. Med. Res. Rev. 2016, 36, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasoon, M.R.A.; Jawad Kadhim, N. Improvement of the selectivity index and cytotoxicity of doxorubicin by Panax ginseng extract. Arch. Razi Inst. 2021, 76, 659–666. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Phytochemical Compound | RT | LRI | Score | Peak Area | Peak Area | Putative Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Min) | (Exp.) | (%) | (Counts) | (%) | (Library) | ||

| 1 | n-Hexane | 2.34 | – | 93 | 2,468,433 | 3.24 | NIST 11 |

| 2 | α-Pinene | 8.60 | 816 | 95 | 242,734 | 0.32 | FFNSC 1.3 |

| 3 | Octan-3-one | 10.31 | 846 | 96 | 590,837 | 0.77 | FFNSC 1.3 |

| 4 | Trifluoroacetyl-lavandulol | 10.49 | 849 | 67 | 540,636 | 0.71 | NIST 11 |

| 5 | Acetic acid hexyl ester | 11.25 | 862 | 97 | 626,875 | 0.82 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 6 | o-Cymene | 11.69 | 870 | 95 | 252,386 | 0.33 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 7 | Eucalyptol | 11.94 | 874 | 96 | 1,075,399 | 1.41 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 8 | Trans-β-Ocimene | 12.16 | 878 | 95 | 4,682,461 | 6.14 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 9 | Trans-β-Ocimene | 12.53 | 885 | 89 | 1,884,034 | 2.47 | NIST 11 |

| 10 | 1,6-Octadien-3-ol, 3,7-dimethyl-(Linalool) | 14.48 | 921 | 97 | 20,589,825 | 26.99 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 11 | 3-Acetoxy-1-octene | 14.81 | 928 | 96 | 818,961 | 1.07 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 12 | 2,3,3-Trimethyl-1,4-Pentadiene | 16.83 | 968 | 74 | 1,350,399 | 1.77 | NIST 11 |

| 13 | Terpinen-4-ol | 17.26 | 977 | 93 | 4,912,866 | 6.44 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 14 | α-Terpineol | 17.71 | 985 | 89 | 766,231 | 1.00 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 15 | 1,6-Octadien-3-ol, 3,7-dimethyl-, formate (linalyl acetate) | 20.02 | 1036 | 98 | 23,927,019 | 31.36 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 16 | 4-Hexen-1-ol, 5-methyl-2-(1-methylethenyl)-, Lavandulyl acetate | 21.14 | 1061 | 98 | 4,372,447 | 5.73 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 17 | 2,6-Octadien-1-ol, 3,7-dimethyl-, acetate, (Z)- | 23.58 | 1119 | 93 | 279,904 | 0.37 | FFNSC 1.3 + NIST 11 |

| 18 | 3,7-Dimethyl-2,6-octadienyl acetate | 24.20 | 1135 | 94 | 717,837 | 0.94 | FFNSC 1.3 |

| 19 | (E)-Caryphyllene | 25.57 | 1169 | 98 | 3,032,598 | 3.98 | FFNSC 1.3 |

| 20 | (E)-β-Famesene | 26.57 | 1195 | 84 | 2,791,995 | 3.66 | NIST 11 |

| 21 | Caryophyllene oxide | 30.56 | 1306 | 92 | 366,199 | 0.48 | FFNSC 1.3 |

| Candida Species | L. angustifolia Essential Oil (μg/mL) | SA (μg/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual | TTZ Assays | SI | FLU | AB | |||

| MIC | MFC | MIC100 | MIC50 | MIC | MIC | ||

| C. albicans (ATCC 90028) | 1000 | 2000 | 2000 | 958 | 0.438 | 1 | 1 |

| C. albicans (ATCC MYA-2876) | 1000 | 4000 | 4000 | 772 | 0.544 | 1 | 0.25 |

| C. glabrata (IZ07) | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 356 | 1.180 | 8 | 0.25 |

| C. lusitaniae (ATCC 42720) | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 1117 | 0.376 | 1 | 0.5 |

| C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) | 1000 | 2000 | 1000 | 701 | 0.599 | 2 | 0.25 |

| D. rugosa (ATCC 10571) | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 483 | 0.870 | 1 | 0.25 |

| I. orientalis (ATCC 6258) | 1000 | 2000 | 2000 | 709 | 0.592 | 32 | 0.25 |

| M. guilliermondii (ATCC 6260) | 125 | 500 | 125 | 73 | 5.753 | 1 | 0.25 |

| Treatment | 1½ h | 6 h | 24 h | 48 h | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | SMIC | Mean ± SD | SMIC | Mean ± SD | SMIC | Mean ± SD | SMIC | |

| L. angustifolia Mill. essential oil (μg/mL) | ||||||||

| GC F | 2.568 ± 0.219 | 0.0 | 2.612 ± 0.064 | 0.0 | 2.177 ± 0.271 | 0.0 | 2.024 ± 0.594 | 0.0 |

| 312.5 E | 1.923 ± 0.230 | 25.6 | 2.230 ± 0.045 | 14.8 | 1.272 ± 0.072 | 42.5 | 1.934 ± 0.059 | 4.5 |

| 625 E | 1.863 ± 0.239 | 28.0 | 2.178 ± 0.092 | 16.9 | 1.262 ± 0.152 | 43.0 | 1.839 ± 0.015 | 9.3 |

| 1250 D | 1.451 ± 0.230 | 44.3 | 1.492 ± 0.305 | 43.6 | 1.127 ± 0.230 | 49.3 | 1.793 ± 0.128 | 11.7 |

| 2500 C | 0.621 ± 0.185 | 77.3 | 0.323 ± 0.096 | 89.1 | 0.794 ± 0.022 | 64.9 | 1.603 ± 0.338 | 21.3 |

| 5000 C | 0.492 ± 0.083 | 82.4 | 0.303 ± 0.101 | 89.8 | 0.632 ± 0.091 | 72.5 | 1.417 ± 0.150 | 30.7 |

| 10,000 B | 0.329 ± 0.063 | 88.8 | 0.256 ± 0.041 | 91.7 | 0.284 ± 0.046 | 88.9 | 0.662 ± 0.039 | 68.8 |

| 20,000 A | 0.069 ± 0.001 | 99.1 | 0.206 ± 0.172 | 93.6 | 0.091 ± 0.031 | 97.9 | 0.136 ± 0.079 | 95.3 |

| 40,000 A | 0.060 ± 0.011 | 99.5 | 0.064 ± 0.004 | 99.2 | 0.059 ± 0.003 | 99.4 | 0.094 ± 0.030 | 97.5 |

| SC A | 0.046 ± 0.002 | 100 | 0.044 ± 0.004 | 100 | 0.045 ± 0.001 | 100 | 0.048 ± 0.001 | 100 |

| RA (SMIC) | y = −0.0252x + 2.5677 | y = −0.0257x + 2.6119 | y = −0.0213x + 2.1769 | y = −0.0198x + 2.0241 | ||||

| Fluconazole (μg/mL) | ||||||||

| GC H | 0.958 ± 0.019 | 0.0 | 1.222 ± 0.022 | 0.0 | 1.318 ± 0.178 | 0.0 | 2.095 ± 0.099 | 0.0 |

| 0.125 G | 0.927 ± 0.082 | 3.4 | 1.221 ± 0.079 | 0.0 | 0.878 ± 0.075 | 34.6 | 1.830 ± 0.043 | 12.9 |

| 0.25 FG | 0.877 ± 0.046 | 8.9 | 1.172 ± 0.151 | 4.2 | 0.865 ± 0.083 | 35.7 | 1.795 ± 0.076 | 14.6 |

| 0.5 EFG | 0.876 ± 0.004 | 9.0 | 1.144 ± 0.033 | 6.6 | 0.852 ± 0.071 | 36.7 | 1.766 ± 0.039 | 16.1 |

| 1 DEFG | 0.876 ± 0.015 | 9.0 | 1.067 ± 0.123 | 13.1 | 0.842 ± 0.051 | 37.5 | 1.721 ± 0.075 | 18.2 |

| 2 CDEF | 0.834 ± 0.039 | 13.6 | 1.046 ± 0.046 | 14.9 | 0.817 ± 0.039 | 39.4 | 1.711 ± 0.026 | 18.7 |

| 4 BCDE | 0.832 ± 0.038 | 13.8 | 1.007 ± 0.046 | 18.2 | 0.785 ± 0.098 | 42.0 | 1.668 ± 0.094 | 20.8 |

| 8 BCD | 0.814 ± 0.021 | 15.7 | 0.967 ± 0.034 | 21.6 | 0.765 ± 0.081 | 43.5 | 1.657 ± 0.115 | 21.4 |

| 16 BC | 0.811 ± 0.058 | 16.1 | 0.893 ± 0.139 | 27.9 | 0.754 ± 0.012 | 44.4 | 1.631 ± 0.015 | 22.7 |

| 32 B | 0.779 ± 0.101 | 19.6 | 0.889 ± 0.073 | 28.2 | 0.735 ± 0.041 | 45.9 | 1.604 ± 0.012 | 24.0 |

| 64 B | 0.761 ± 0.055 | 21.5 | 0.875 ± 0.095 | 29.4 | 0.717 ± 0.022 | 47.3 | 1.590 ± 0.149 | 24.6 |

| SC A | 0.046 ± 0.000 | 100 | 0.045 ± 0.000 | 100 | 0.045 ± 0.000 | 100 | 0.045 ± 0.000 | 100 |

| RA (SMIC) | y = −0.0091x + 0.9575 | y = −0.0118x + 1.2218 | y = −0.0127x + 1.3178 | y = −0.0205x + 2.0951 | ||||

| Nystatin (μg/mL) | ||||||||

| GC F | 0.974 ± 0.027 | 0.0 | 1.601 ± 0.073 | 0.0 | 1.207 ± 0.145 | 0.0 | 2.041 ± 0.217 | 0.0 |

| 0.125 EF | 0.935 ± 0.030 | 4.2 | 1.495 ± 0.286 | 6.7 | 0.847 ± 0.038 | 31.1 | 1.923 ± 0.060 | 5.9 |

| 0.25 DE | 0.905 ± 0.016 | 7.5 | 1.372 ± 0.129 | 14.7 | 0.818 ± 0.126 | 33.6 | 1.869 ± 0.098 | 8.6 |

| 0.5 DE | 0.860 ± 0.018 | 12.3 | 1.366 ± 0.082 | 15.0 | 0.799 ± 0.025 | 35.1 | 1.838 ± 0.017 | 10.1 |

| 1 DE | 0.832 ± 0.016 | 15.3 | 1.163 ± 0.040 | 28.1 | 0.762 ± 0.066 | 38.3 | 1.811 ± 0.077 | 11.5 |

| 2 DE | 0.829 ± 0.054 | 15.6 | 1.103 ± 0.112 | 31.9 | 0.753 ± 0.010 | 39.2 | 1.810 ± 0.065 | 11.6 |

| 4 D | 0.791 ± 0.088 | 19.8 | 1.054 ± 0.136 | 35.1 | 0.726 ± 0.271 | 41.5 | 1.711 ± 0.166 | 16.5 |

| 8 C | 0.722 ± 0.040 | 27.2 | 0.380 ± 0.240 | 78.3 | 0.422 ± 0.388 | 67.7 | 1.572 ± 0.091 | 23.4 |

| 16 B | 0.702 ± 0.023 | 29.3 | 0.341 ± 0.164 | 80.7 | 0.228 ± 0.168 | 84.4 | 0.416 ± 0.444 | 81.3 |

| 32 A | 0.062 ± 0.004 | 98.1 | 0.058 ± 0.011 | 98.9 | 0.188 ± 0.144 | 87.8 | 0.373 ± 0.102 | 83.4 |

| 64 A | 0.048 ± 0.005 | 99.6 | 0.051 ± 0.004 | 99.3 | 0.106 ± 0.078 | 94.9 | 0.149 ± 0.083 | 94.6 |

| SC A | 0.046 ± 0.000 | 100 | 0.045 ± 0.000 | 100 | 0.045 ± 0.000 | 100 | 0.046 ± 0.000 | 100 |

| RA (SMIC) | y = −0.0093x + 0.9744 | y = −0.0156x + 1.6006 | y = −0.0116x + 1.2071 | y = −0.02x + 2.0408 | ||||

| Morphology | Treatment | Time | |||

| 0 h A | 1 h A | 2 h B | 3 h B | ||

| Yeast | CG B | 4.73 ± 0.231 | 4.40 ± 0.477 | 1.22 ± 0.603 | 0.27 ± 0.252 |

| 2000 μg/mL A | 4.43 ± 0.451 | 4.28 ± 0.493 | 3.97 ± 0.161 | 4.27 ± 0.161 | |

| 4000 μg/mL A | 4.27 ± 0.284 | 4.67 ± 0.225 | 4.63 ± 0.306 | 4.47 ± 0.237 | |

| Tween 80 B | 4.97 ± 0.189 | 3.58 ± 0.404 | 1.75 ± 0.458 | 0.80 ± 0.346 | |

| Morphology | Treatment | Time | |||

| 0 h D | 1 h D | 2 h C | 3 h B | ||

| Germ tube | CG C | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.67 ± 0.605 | 6.10 ± 2.311 |

| 2000 μg/mL D | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.017 ± 0.029 | |

| 4000 μg/mL D | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| Tween® 80 C | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.67 ± 0.333 | 4.48 ± 0.506 |

| Treatment—L. angustifolia Essential Oil | Mean ± SD | CI |

|---|---|---|

| GC A | 0.669 ± 0.127 | 0.0 |

| 78.1 μg/mL (0.000097% Tween 80) A | 0.668 ± 0.110 | 0.3 |

| 156.2 μg/mL (0.00019% Tween 80) AB | 0.528 ± 0.190 | 22.7 |

| 312.5 μg/mL (0.00039% Tween 80) BC | 0.397 ± 0.165 | 44.0 |

| 625 μg/mL (0.00078% Tween 80) C | 0.286 ± 0.090 | 61.8 |

| 1250 μg/mL (0.00156% Tween 80) C | 0.283 ± 0.103 | 62.3 |

| 2500 μg/mL (0.00312% Tween 80) C | 0.280 ± 0.048 | 62.9 |

| 5000 μg/mL (0.00625% Tween 80) C | 0.276 ± 0.063 | 63.5 |

| 10,000 μg/mL (0.125% Tween 80) C | 0.274 ± 0.039 | 63.8 |

| 20,000 μg/mL (0.025% Tween 80) C | 0.264 ± 0.042 | 65.4 |

| 40,000 μg/mL (0.05% Tween 80) C | 0.254 ± 0.059 | 67.0 |

| SC D | 0.048 ± 0.001 | 100.2 |

| Tmax BC | 0.396 ± 0.052 | 44.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bassinello, V.; Boriollo, M.F.G.; Barbosa, J.P.; Bernardo, W.L.d.C.; Oliveira, M.C.; Dias, C.T.d.S.; Sousa, C.P.d. Lavandula angustifolia Essential Oil as a Developmental Inhibitor of Candida Species and Biofilms. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010041

Bassinello V, Boriollo MFG, Barbosa JP, Bernardo WLdC, Oliveira MC, Dias CTdS, Sousa CPd. Lavandula angustifolia Essential Oil as a Developmental Inhibitor of Candida Species and Biofilms. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleBassinello, Vanessa, Marcelo Fabiano Gomes Boriollo, Janaina Priscila Barbosa, Wagner Luís de Carvalho Bernardo, Mateus Cardoso Oliveira, Carlos Tadeu dos Santos Dias, and Cristina Paiva de Sousa. 2026. "Lavandula angustifolia Essential Oil as a Developmental Inhibitor of Candida Species and Biofilms" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010041

APA StyleBassinello, V., Boriollo, M. F. G., Barbosa, J. P., Bernardo, W. L. d. C., Oliveira, M. C., Dias, C. T. d. S., & Sousa, C. P. d. (2026). Lavandula angustifolia Essential Oil as a Developmental Inhibitor of Candida Species and Biofilms. Antibiotics, 15(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010041