Antibiotic Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Related Enterobacterales: Molecular Mechanisms, Mobile Elements, and Therapeutic Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Combination (ATB/Inhibitor) | Active Against | Inactive/Limitations | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftazidime/avibactam (CZA) | KPC, OXA-48-like | MBLs | Resistance via KPC mutations (e.g., D179Y in Ω-loop), porin changes (OmpK35/36) | [23] |

| Meropenem/vaborbactam (MVB) | KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae | Limited against OXA-48-like, inactive against MBLs | — | [35] |

| Imipenem/cilastatin/ relebactam (IMI/REL) | KPC-producing K. pneumoniae | Limited against OXA-48-like, inactive against MBLs | Resistance via OmpK36 disruption combined with increased expression of KPC enzymes | [36] |

| Cefiderocol | Broad spectrum, including MBL producers | Resistance via cirA/tonB disruption, especially in MBL backgrounds | Requires careful AST and stewardship | [29,33] |

| Aztreonam/avibactam (ATM/AVI) | MBL producers (also ESBL, AmpC, KPC) | — | Approved by EMA [37] and FDA [38] for cIAI, HAP/VAP, and cUTI. Resistance via PBP3 modifications (Escherichia coli), high-level AmpC (e.g., CMY-42), KPC mutations, porin loss, and efflux pump overexpression (K. pneumoniae) | [39] |

| Cefepime/enmetazobactam (FEP/ENM) | ESBL-producing Enterobacterales | — | Approved by EMA [40]; carbapenem-sparing option | [41] |

| Cefepime/taniborbactam (FEP/TAN) | KPC, OXA-48-like, some MBLs | Not approved by FDA [42]; limited clinical availability | Promising in vitro activity | [43] |

| Cefepime/zidebactam (FEP/ZID) | KPC, OXA-48-like, many MBL producers | — | Zidebactam binds PBP2 + has BLI activity; Phase 3 trials positive | [43] |

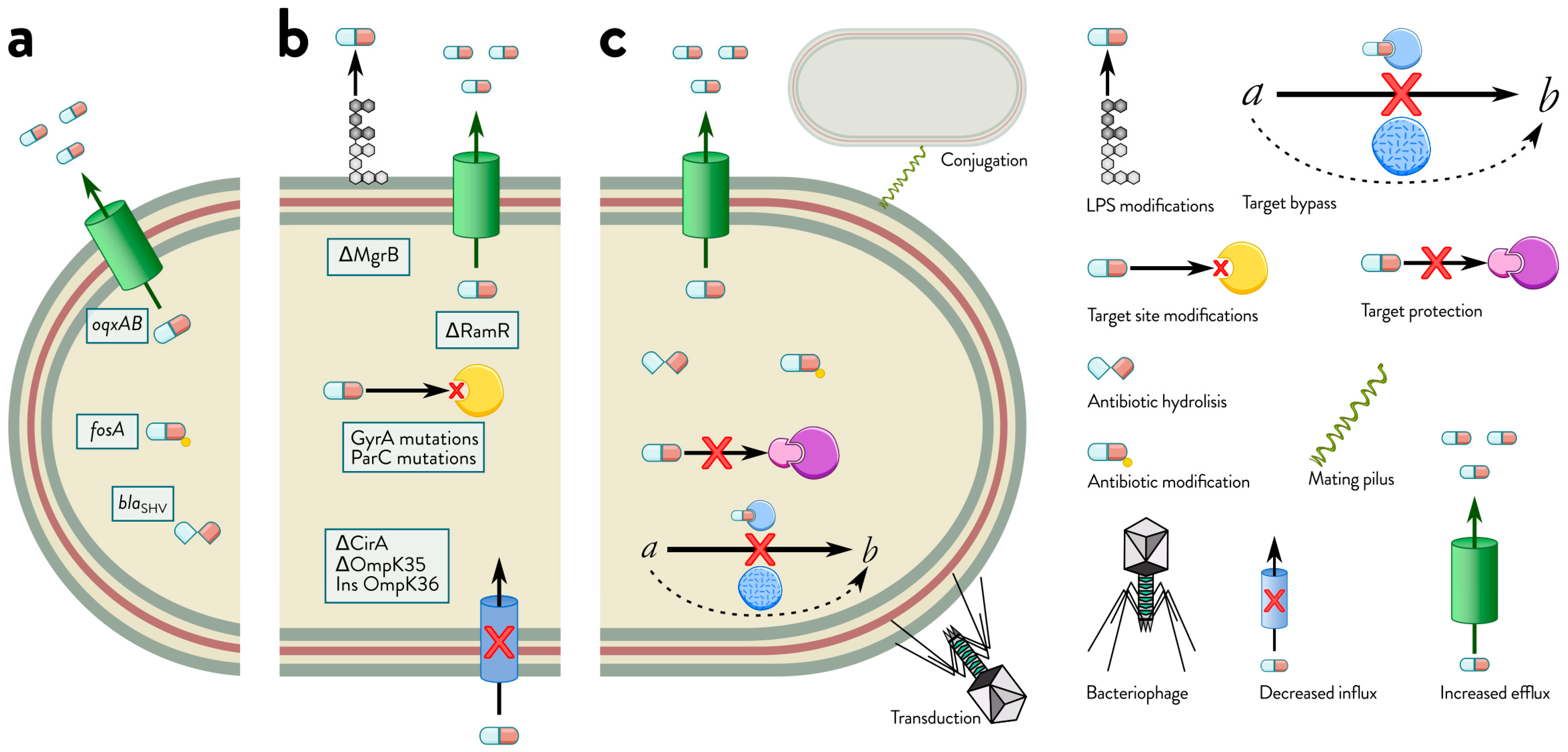

2. Comprehensive Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Klebsiella spp.

2.1. Mechanisms of Intrinsic Resistance

2.2. Mechanisms of Acquired Resistance: Horizontal Gene Transfer and Mutational Adaptations in Bacteria

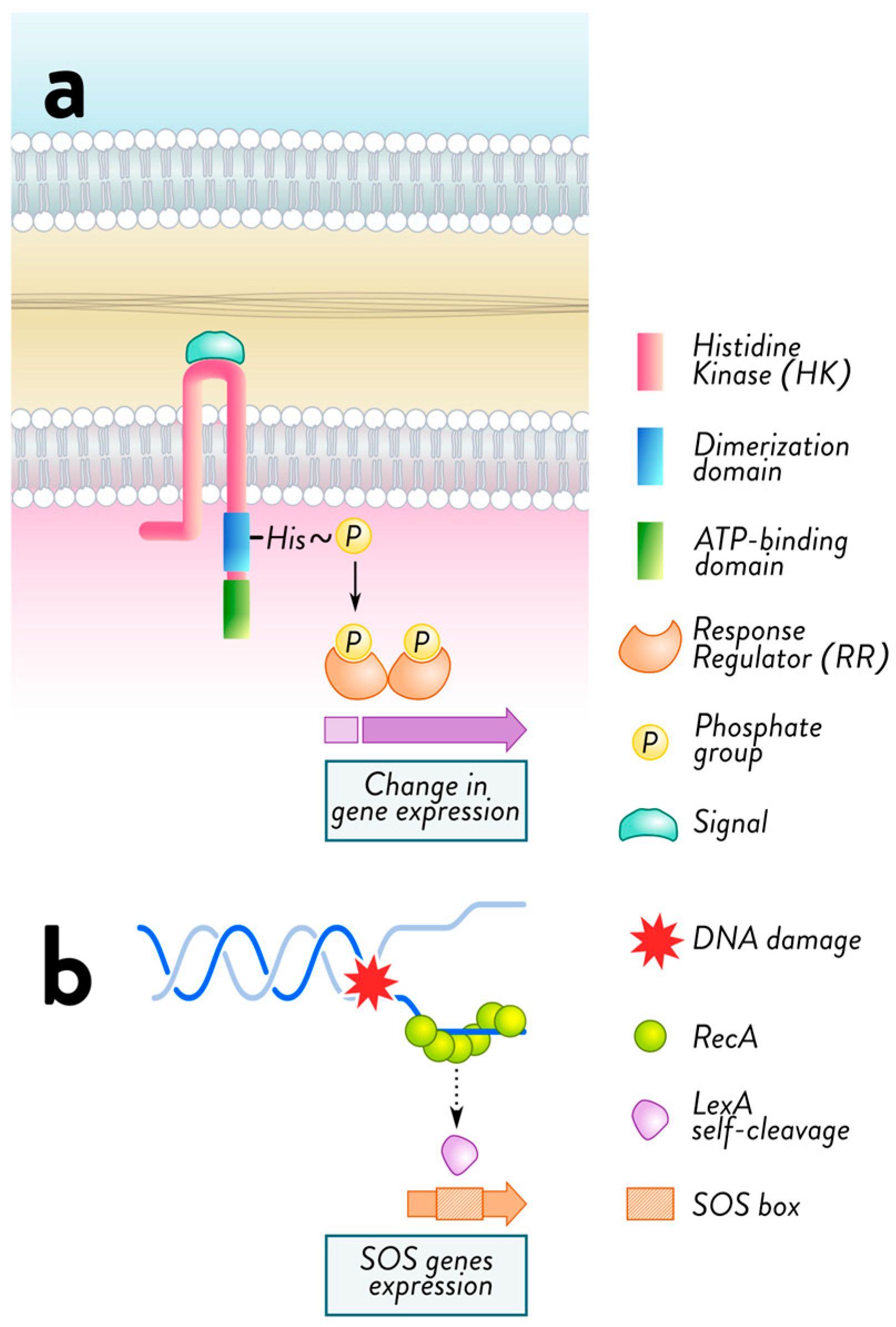

2.3. Mechanisms of Adaptive Resistance

2.4. Interplay of Intrinsic, Acquired, and Adaptive Resistance Mechanisms in Bacterial Survival

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| acyl-PGs | acyl-glycerophosphoglycerols |

| AMR | antimicrobial resistance |

| ARGs | antibiotic resistance genes |

| AST | antimicrobial susceptibility testing |

| CAP | cationic antimicrobial peptide |

| CIP | ciprofloxacin |

| CMY | active on cephamycins |

| CPS | capsular polysaccharide |

| CTX-M | cefotaxime-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase–Munich |

| DHA | discovered at Dhahran, Saudi Arabia |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EPIs | efflux pump inhibitors |

| ESBL | extended-spectrum beta-lactamase |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FOX | active on cefoxitin |

| H-NS | histone-like nucleoid structuring protein |

| IMP | active on imipenem |

| Inc | incompatibility |

| hvKp | hypervirulent K. pneumoniae |

| KPC | K. pneumoniae carbapenemase |

| KpSC | K. pneumoniae species complex |

| LEN | from K. pneumoniae strain LEN-1 |

| Lpp | murein-lipoprotein |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MATE | multidrug and toxic compound extrusion |

| MBL | metallo-beta-lactamase |

| mcr | mobile colistin resistance gene |

| MDR | multidrug-resistant |

| MFS | major facilitator superfamily |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MLS | macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin |

| MOX | active on moxalactam |

| MPS | mating pair stabilization |

| NDM | New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase |

| OKP | other K. pneumoniae beta-lactamase |

| OM | outer membrane |

| OMP | outer membrane protein |

| OmpA | outer membrane protein A |

| OXA | active on oxacillin |

| PAL | peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein |

| PBP | penicillin-binding protein |

| (p)ppGpp | guanosine tetra- and pentaphosphate (stringent response alarmone) |

| RND | resistance nodulation cell division |

| SHV | sulfhydryl reagent variable |

| SMR | small multidrug resistance |

| TCS | two-component system |

| TEM | Temoneira |

| VIM | Verona integron-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase |

| XDR | extensively drug-resistant |

References

- Podschun, R.; Ullmann, U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: Epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K.L.; Lam, M.M.C.; Holt, K.E. Population genomics of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffet, A.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Rendueles, O. Nutrient conditions are primary drivers of bacterial capsule maintenance in Klebsiella. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2021, 288, 20202876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, X.; An, H.; Wang, J.; Ding, M.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Ji, Q.; Qu, F.; Wang, H.; et al. Capsule type defines the capability of Klebsiella pneumoniae in evading Kupffer cell capture in the liver. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, S.; Altarriba, M.; Izquierdo, L.; Nogueras, M.M.; Regué, M.; Tomás, J.M. Cloning and Sequencing of the Klebsiella pneumoniae O5wb Gene Cluster and Its Role in Pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 2435–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.A.; Marr, C.M. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00001-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.C.; Li, C.L.; Zhang, S.Y.; Yang, X.F.; Jiang, M. The Global and Regional Prevalence of Hospital-Acquired Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofad649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peabody, M.A.; Van Rossum, T.; Lo, R.; Brinkman, F.S. Evaluation of shotgun metagenomics sequence classification methods using in silico and in vitro simulated communities. BMC Bioinform. 2015, 16, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K.L.; Holt, K.E. Klebsiella pneumoniae as a key trafficker of drug resistance genes from environmental to clinically important bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 45, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.N. Microbial etiologies of hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, S81–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, A.S.; Bajwa, R.P.; Russo, T.A. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: A new and dangerous breed. Virulence 2013, 4, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialek-Davenet, S.; Criscuolo, A.; Ailloud, F.; Passet, V.; Jones, L.; Delannoy-Vieillard, A.S.; Garin, B.; Le Hello, S.; Arlet, G.; Nicolas-Chanoine, M.H.; et al. Genomic definition of hypervirulent and multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal groups. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1812–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroll, C.; Barken, K.B.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Struve, C. Role of type 1 and type 3 fimbriae in Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm formation. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, N.R.; Lazazzera, B.A. Environmental signals and regulatory pathways that influence biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 52, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, K.K.; Lam, M.M.C.; Wick, R.R.; Wyres, K.L.; Bachman, M.; Baker, S.; Barry, K.; Brisse, S.; Campino, S.; Chiaverini, A.; et al. Diversity, functional classification and genotyping of SHV beta-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb. Genom. 2024, 10, 001294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUCAST [Internet]. Expected Resistant Phenotypes. Version 1.2. 2023. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/expert_rules_and_expected_phenotypes/expected_phenotypes (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Leverstein-van Hall, M.A.; Dierikx, C.M.; Cohen Stuart, J.; Voets, G.M.; van den Munckhof, M.P.; van Essen-Zandbergen, A.; Platteel, T.; Fluit, A.C.; van de Sande-Bruinsma, N.; Scharinga, J.; et al. Dutch patients, retail chicken meat and poultry share the same ESBL genes, plasmids and strains. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdarska, V.; Kolar, M.; Mlynarcik, P. Occurrence of beta-lactamases in bacteria. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2024, 122, 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDSA. Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. 2024. Available online: https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/amr-guidance/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Keam, S.J. Cefepime/Enmetazobactam: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Drug Approval Package: AVYCAZ (Ceftazidime-Avibactam). Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2015/206494Orig1s000TOC.cfm (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- EMA Zavicefta|European Medicines Agency. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zavicefta (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Xu, T.T.; Guo, Y.Q.; Ji, Y.; Wang, B.H.; Zhou, K. Epidemiology and Mechanisms of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Engineering 2022, 11, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillyer, T.; Shin, W.S. Meropenem/Vaborbactam-A Mechanistic Review for Insight into Future Development of Combinational Therapies. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, T.A.; Gallagher, J.C. A Clinical Review and Critical Evaluation of Imipenem-Relebactam: Evidence to Date. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 4297–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambler, R.P. The structure of beta-lactamases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1980, 289, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K. Past and Present Perspectives on beta-Lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01076-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navon-Venezia, S.; Kondratyeva, K.; Carattoli, A. Klebsiella pneumoniae: A major worldwide source and shuttle for antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.H.; Yang, D.Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Ni, W.T. Cefiderocol for the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Systematic Review of Currently Available Evidence. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 896971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palombo, M.; Secci, B.; Bovo, F.; Gatti, M.; Ambretti, S.; Gaibani, P. In Vitro Evaluation of Increasing Avibactam Concentrations on Ceftazidime Activity Against Ceftazidime/Avibactam-Susceptible and Resistant KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Arcari, G.; Bibbolino, G.; Sacco, F.; Tomolillo, D.; Di Lella, F.M.; Trancassini, M.; Faino, L.; Venditti, M.; Antonelli, G.; et al. Evolutionary Trajectories toward Ceftazidime-Avibactam Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0057421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, C.A.; Pierrat, G.; Tenaillon, O.; Bonacorsi, S.; Bercot, B.; Jaouen, E.; Jacquier, H.; Birgy, A. Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase Variants Resistant to Ceftazidime-Avibactam: An Evolutionary Overview. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, 00447-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriz, R.; Spettel, K.; Pichler, A.; Schefberger, K.; Sanz-Codina, M.; Lötsch, F.; Harrison, N.; Willinger, B.; Zeitlinger, M.; Burgmann, H.; et al. In vitro resistance development gives insights into molecular resistance mechanisms against cefiderocol. J. Antibiot. 2024, 77, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polani, R.; De Francesco, A.; Tomolillo, D.; Artuso, I.; Equestre, M.; Trirocco, R.; Arcari, G.; Antonelli, G.; Villa, L.; Prosseda, G.; et al. Cefiderocol Resistance Conferred by Plasmid-Located Ferric Citrate Transport System in KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackel, M.A.; Lomovskaya, O.; Dudley, M.N.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Sahm, D.F. In Vitro Activity of Meropenem-Vaborbactam against Clinical Isolates of KPC-Positive Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01904-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, J.N.; Lodise, T.P. New Perspectives on Antimicrobial Agents: Imipenem-Relebactam. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e00256-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New Antibiotic to Fight Infections Caused by Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria | European Medicines Agency n.d. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/new-antibiotic-fight-infections-caused-multidrug-resistant-bacteria (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- AbbVie. FDA Approves EMBLAVEO™ (Aztreonam and Avibactam) for the Treatment of Adults with Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections with Limited or No Treatment Options. Available online: https://news.abbvie.com/2025-02-07-U-S-FDA-Approves-EMBLAVEO-TM-aztreonam-and-avibactam-for-the-Treatment-of-Adults-With-Complicated-Intra-Abdominal-Infections-With-Limited-or-No-Treatment-Options (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Karaiskos, I.; Galani, I.; Daikos, G.L.; Giamarellou, H. Breaking Through Resistance: A Comparative Review of New Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors (Avibactam, Vaborbactam, Relebactam) Against Multidrug-Resistant Superbugs. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exblifep European Medicines Agency (EMA). 2024. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/exblifep (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Bhowmick, T.; Canton, R.; Pea, F.; Quevedo, J.; Henriksen, A.S.; Timsit, J.F.; Kaye, K.S. Cefepime-enmetazobactam: First approved cefepime-β-lactamase inhibitor combination for multi-drug resistant Enterobacterales. Future Microbiol. 2025, 20, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chris Dall. FDA Rejects New Drug Application for Cefepime-Taniborbactam. Published Online. 27 February 2024. Available online: https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/antimicrobial-stewardship/fda-rejects-new-drug-application-cefepime-taniborbactam (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Katsarou, A.; Stathopoulos, P.; Tzvetanova, I.D.; Asimotou, C.M.; Falagas, M.E. β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combination Antibiotics Under Development. Pathogens 2025, 14, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, E.M.; Trampari, E.; Siasat, P.; Gaya, M.S.; Alav, I.; Webber, M.A.; Blair, J.M.A. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance revisited. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui, Z.; Ocampo-Sosa, A.; Fernandez Martinez, M.; Landolsi, S.; Ferjani, S.; Maamar, E.; Saidani, M.; Slim, A.; Martinez-Martinez, L.; Boutiba-Ben Boubaker, I. Role of association of OmpK35 and OmpK36 alteration and blaESBL and/or blaAmpC genes in conferring carbapenem resistance among non-carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, K.E.; Wertheim, H.; Zadoks, R.N.; Baker, S.; Whitehouse, C.A.; Dance, D.; Jenney, A.; Connor, T.R.; Hsu, L.Y.; Severin, J.; et al. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E3574–E3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, J.; Ladona, M.G.; Segura, C.; Coira, A.; Reig, R.; Ampurdanes, C. SHV-1 beta-lactamase is mainly a chromosomally encoded species-specific enzyme in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 2856–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L.; Walsh, T.R.; Livermore, D.M. The emerging NDM carbapenemases. Trends Microbiol. 2011, 19, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, P.; Cuzon, G.; Naas, T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2009, 9, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Walsh, T.R.; Yi, L.X.; Zhang, R.; Spencer, J.; Doi, Y.; Tian, G.; Dong, B.; Huang, X.; et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: A microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, P.R. Book review: Tackling drug-resistant infections globally. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 7, 110–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, N.; Turton, J.F.; Livermore, D.M. Multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria: The role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 736–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, A.J.; Peirano, G.; Pitout, J.D. The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 565–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitout, J.D.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a Key Pathogen Set for Global Nosocomial Dominance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 5873–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J.R.; Kitchel, B.; Driebe, E.M.; MacCannell, D.R.; Roe, C.; Lemmer, D.; de Man, T.; Rasheed, J.K.; Engelthaler, D.M.; Keim, P.; et al. Genomic Analysis of the Emergence and Rapid Global Dissemination of the Clonal Group 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnin, R.A.; Jousset, A.B.; Chiarelli, A.; Emeraud, C.; Glaser, P.; Naas, T.; Dortet, L. Emergence of New Non–Clonal Group 258 High-Risk Clones among Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase–Producing K. pneumoniae Isolates, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaidullina, E.R.; Schwabe, M.; Rohde, T.; Shapovalova, V.V.; Dyachkova, M.S.; Matsvay, A.D.; Savochkina, Y.A.; Shelenkov, A.A.; Mikhaylova, Y.V.; Sydow, K.; et al. Genomic analysis of the international high-risk clonal lineage Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 395. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turton, J.; Davies, F.; Turton, J.; Perry, C.; Payne, Z.; Pike, R. Hybrid Resistance and Virulence Plasmids in “High-Risk” Clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Including Those Carrying blaNDM-5. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Achille, G.; Cotoloni, G.; Nunzi, I.; Brescini, L.; Fioriti, S.; Armiento, M.; Pocognoli, A.; Giovanetti, E.; Paoletti, C.; Menzo, S.; et al. Diffusion of OXA-48- and NDM-5-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST383 clone in Central Italy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, dkaf397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, A.S.; Kiani, N.; Aghamohammad, S.; Shafiei, M.; Darazam, I.A.; Darabi, S.; Badmasti, F. Clonal dissemination of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in outpatients as fecal-carriages: Predominance of the high-risk clone ST231. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Xiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Lineage-specific evolution and resistance-virulence divergence in Klebsiella pneumoniae ST268: A global population genomic analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e0070325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, T.D.; Wyres, K.L. What defines hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae? Ebiomedicine 2024, 108, 105331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcari, G.; Carattoli, A. Global spread and evolutionary convergence of multidrug-resistant and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae high-risk clones. Pathog. Glob. Health 2023, 117, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicas, T.I.; Hancock, R.E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane permeability: Isolation of a porin protein F-deficient mutant. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 153, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido, H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. MMBR 2003, 67, 593–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, G.E. The structure of bacterial outer membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)–Biomembr. 2002, 1565, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, B.D.; Trent, M.S. Fortifying the barrier: The impact of lipid A remodelling on bacterial pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlynarcik, P.; Kolar, M. Molecular mechanisms of polymyxin resistance and detection of mcr genes. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky. Olomouc Czech Repub. 2019, 163, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, T.; Li, X.; Li, N.; Xie, Z.; Yang, F.; You, X. CrrAB regulates PagP-mediated glycerophosphoglycerol palmitoylation in the outer membrane of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Lipid Res. 2022, 63, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.F.; Liu, J.Y.; Pan, Y.J.; Wu, M.C.; Lin, T.L.; Huang, Y.T.; Wang, J.T. Klebsiella pneumoniae peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein and murein lipoprotein contribute to serum resistance, anti-phagocytosis and proinflammatory cytokine stimulation. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 208, 1580–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llobet, E.; March, C.; Gimenez, P.; Bengoechea, J.A. Klebsiella pneumoniae OmpA confers resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Sureda, L.; Juan, C.; Domenech-Sanchez, A.; Alberti, S. Role of Klebsiella pneumoniae LamB Porin in antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 1803–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, F.M.; Dib-Hajj, F.; Shang, W.C.; Gootz, T.D. High-level carbapenem resistance in a Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolate is due to the combination of blaACT-1 β-lactamase production, porin OmpK35/36 insertional inactivation, and down-regulation of the phosphate transport porin PhoE. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 3396–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, N.; Lin, Z.; Ba, X.; Zhuo, C.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Yao, L.; Liu, B.; et al. Mutations in porin LamB contribute to ceftazidime-avibactam resistance in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 2042–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, E.; Kojima, S.; Nikaido, H. Klebsiella pneumoniae Major Porins OmpK35 and OmpK36 Allow More Efficient Diffusion of beta-Lactams than Their Escherichia coli Homologs OmpF and OmpC. J. Bacteriol. 2016, 198, 3200–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikaido, H.; Rosenberg, E.Y. Porin channels in Escherichia coli: Studies with liposomes reconstituted from purified proteins. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 153, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Alles, S.; Alberti, S.; Alvarez, D.; Domenech-Sanchez, A.; Martinez-Martinez, L.; Gil, J.; Tomas, J.M.; Benedi, V.J. Porin expression in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiology 1999, 145, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, L.M.; Steward, C.D.; Tenover, F.C. gyrA mutations associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in eight species of Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 2661–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardanuy, C.; Linares, J.; Dominguez, M.A.; Hernandez-Alles, S.; Benedi, V.J.; Martinez-Martinez, L. Outer membrane profiles of clonally related Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from clinical samples and activities of cephalosporins and carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 1636–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, P.A.; Urban, C.; Mariano, N.; Projan, S.J.; Rahal, J.J.; Bush, K. Imipenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with the combination of ACT-1, a plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamase, and the loss of an outer membrane protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martinez, L.; Hernandez-Alles, S.; Alberti, S.; Tomas, J.M.; Benedi, V.J.; Jacoby, G.A. In vivo selection of porin-deficient mutants of Klebsiella pneumoniae with increased resistance to cefoxitin and expanded-spectrum-cephalosporins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martinez, L.; Pascual, A.; Hernandez-Alles, S.; Alvarez-Diaz, D.; Suarez, A.I.; Tran, J.; Benedi, V.J.; Jacoby, G.A. Roles of beta-lactamases and porins in activities of carbapenems and cephalosporins against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 1669–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.L.C.; David, S.; Sanchez-Garrido, J.; Woo, J.Z.; Low, W.W.; Morecchiato, F.; Giani, T.; Rossolini, G.M.; Beis, K.; Brett, S.J.; et al. Recurrent emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenem resistance mediated by an inhibitory ompK36 mRNA secondary structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2203593119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialek-Davenet, S.; Mayer, N.; Vergalli, J.; Duprilot, M.; Brisse, S.; Pages, J.M.; Nicolas-Chanoine, M.H. In-vivo loss of carbapenem resistance by extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae during treatment via porin expression modification. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.I.; Picao, R.C.; Almeida, L.G.; Lima, N.C.; Girardello, R.; Vivan, A.C.; Xavier, D.E.; Barcellos, F.G.; Pelisson, M.; Vespero, E.C.; et al. Comparative analysis of the complete genome of KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Kp13 reveals remarkable genome plasticity and a wide repertoire of virulence and resistance mechanisms. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, V.B.; Venkataramaiah, M.; Mondal, A.; Vaidyanathan, V.; Govil, T.; Rajamohan, G. Functional characterization of a novel outer membrane porin KpnO, regulated by PhoBR two-component system in Klebsiella pneumoniae NTUH-K2044. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Sureda, L.; Domenech-Sanchez, A.; Barbier, M.; Juan, C.; Gasco, J.; Alberti, S. OmpK26, a novel porin associated with carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4742–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanheira, M.; Deshpande, L.M.; Mills, J.C.; Jones, R.N.; Soave, R.; Jenkins, S.G.; Schuetz, A.N. Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolate from a New York City Hospital Belonging to Sequence Type 258 and Carrying blaKPC-2 and blaVIM-4. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 1924–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenech-Sanchez, A.; Hernandez-Alles, S.; Martinez-Martinez, L.; Benedi, V.J.; Alberti, S. Identification and characterization of a new porin gene of Klebsiella pneumoniae: Its role in beta-lactam antibiotic resistance. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 2726–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düzgün, A.Ö. From Turkey: First Report of KPC-3-and CTX-M-27-Producing Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147 Clone Carrying OmpK36 and Ompk37 Porin Mutations. Microb. Drug Resist. 2021, 27, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, P.A. MDR Pumps as Crossroads of Resistance: Antibiotics and Bacteriophages. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeil, H.E.; Alav, I.; Torres, R.C.; Rossiter, A.E.; Laycock, E.; Legood, S.; Kaur, I.; Davies, M.; Wand, M.; Webber, M.A.; et al. Identification of binding residues between periplasmic adapter protein (PAP) and RND efflux pumps explains PAP-pump promiscuity and roles in antimicrobial resistance. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1008101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, V.; Tzakas, P.; Buckley, A.; Piddock, L.J. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains are difficult to select in the absence of AcrB and TolC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papkou, A.; Hedge, J.; Kapel, N.; Young, B.; MacLean, R.C. Efflux pump activity potentiates the evolution of antibiotic resistance across S. aureus isolates. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saw, H.T.; Webber, M.A.; Mushtaq, S.; Woodford, N.; Piddock, L.J. Inactivation or inhibition of AcrAB-TolC increases resistance of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae to carbapenems. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewoye, L.; Sutherland, A.; Srikumar, R.; Poole, K. The mexR repressor of the mexAB-oprM multidrug efflux operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Characterization of mutations compromising activity. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 4308–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, J.; Alvarez-Ortega, C.; Linares, J.F.; Rojo, F.; Kohler, T.; Martinez, J.L. Overproduction of the multidrug efflux pump MexEF-OprN does not impair Pseudomonas aeruginosa fitness in competition tests, but produces specific changes in bacterial regulatory networks. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1968–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, P.; Linares, J.F.; Ruiz-Diez, B.; Campanario, E.; Navas, A.; Baquero, F.; Martinez, J.L. Fitness of in vitro selected Pseudomonas aeruginosa nalB and nfxB multidrug resistant mutants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 50, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, K. Efflux-mediated resistance to fluoroquinolones in gram-positive bacteria and the mycobacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2595–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, T.; Tsuchiya, T. Multidrug efflux transporters in the MATE family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2009, 1794, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, W.; Minato, Y.; Dodan, H.; Onishi, M.; Tsuchiya, T.; Kuroda, T. Characterization of MATE-type multidrug efflux pumps from Klebsiella pneumoniae MGH78578. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla, E.; Llobet, E.; Domenech-Sanchez, A.; Martinez-Martinez, L.; Bengoechea, J.A.; Alberti, S. Klebsiella pneumoniae AcrAB efflux pump contributes to antimicrobial resistance and virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, T.; Sheng, Z.K.; Ye, M.; Xu, X.; Wang, M. Efflux pumps AcrAB and OqxAB contribute to nitrofurantoin resistance in an uropathogenic Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 54, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolivos, S.; Cayron, J.; Dedieu, A.; Page, A.; Delolme, F.; Lesterlin, C. Role of AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump in drug-resistance acquisition by plasmid transfer. Science 2019, 364, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.L.; Sanchez, M.B.; Martinez-Solano, L.; Hernandez, A.; Garmendia, L.; Fajardo, A.; Alvarez-Ortega, C. Functional role of bacterial multidrug efflux pumps in microbial natural ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butaye, P.; Cloeckaert, A.; Schwarz, S. Mobile genes coding for efflux-mediated antimicrobial resistance in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2003, 22, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Jamal, S.B.; Hassan, S.S.; Carvalho, P.; Almeida, S.; Barh, D.; Ghosh, P.; Silva, A.; Castro, T.L.P.; Azevedo, V. Two-Component Signal Transduction Systems of Pathogenic Bacteria As Targets for Antimicrobial Therapy: An Overview. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.S.; Chen, H.W.; Zhang, R.Y.; Huang, C.Y.; Shen, C.F. The Expression Levels of Outer Membrane Proteins STM1530 and OmpD, Which Are Influenced by the CpxAR and BaeSR Two-Component Systems, Play Important Roles in the Ceftriaxone Resistance of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 3829–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayol, A.; Nordmann, P.; Brink, A.; Poirel, L. Heteroresistance to Colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae Associated with Alterations in the PhoPQ Regulatory System. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 2780–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, L.; Yang, M.; Chen, C.; Li, X.; Tian, J.; Luo, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, M. Reduced porin expression with EnvZ-OmpR, PhoPQ, BaeSR two-component system down-regulation in carbapenem resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae based on proteomic analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 170, 105686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.B.; Vaidyanathan, V.; Mondal, A.; Rajamohan, G. Role of the two component signal transduction system CpxAR in conferring cefepime and chloramphenicol resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae NTUH-K2044. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Peng, H.L. Molecular characterization of the PhoPQ-PmrD-PmrAB mediated pathway regulating polymyxin B resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannatelli, A.; Di Pilato, V.; Giani, T.; Arena, F.; Ambretti, S.; Gaibani, P.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Rossolini, G.M. In vivo evolution to colistin resistance by PmrB sensor kinase mutation in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with low-dosage colistin treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4399–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucena, A.C.R.; Ferrarini, M.G.; de Oliveira, W.K.; Marcon, B.H.; Morello, L.G.; Alves, L.R.; Faoro, H. Modulation of Klebsiella pneumoniae Outer Membrane Vesicle Protein Cargo under Antibiotic Treatment. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamayo, R.; Ryan, S.S.; McCoy, A.J.; Gunn, J.S. Identification and genetic characterization of PmrA-regulated genes and genes involved in polymyxin B resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 6770–6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandeya, A.; Ojo, I.; Alegun, O.; Wei, Y. Periplasmic Targets for the Development of Effective Antimicrobials against Gram-Negative Bacteria. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 2337–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Sciuto, A.; Fernández-Piñar, R.; Bertuccini, L.; Iosi, F.; Superti, F.; Imperi, F. The Periplasmic Protein TolB as a Potential Drug Target in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, S.; Tokuda, H. Sorting of bacterial lipoproteins to the outer membrane by the Lol system. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 619, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, R.; Vithanage, N.; Harrison, P.; Seemann, T.; Coutts, S.; Moffatt, J.H.; Nation, R.L.; Li, J.; Harper, M.; Adler, B.; et al. Colistin-resistant, lipopolysaccharide-deficient Acinetobacter baumannii responds to lipopolysaccharide loss through increased expression of genes involved in the synthesis and transport of lipoproteins, phospholipids, and poly-beta-1,6-N-acetylglucosamine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz, F.; Frost, L.S.; Meyer, R.J.; Zechner, E.L. Conjugative DNA metabolism in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, W.W.; Seddon, C.; Beis, K.; Frankel, G. The Interaction of the F-Like Plasmid-Encoded TraN Isoforms with Their Cognate Outer Membrane Receptors. J. Bacteriol. 2023, 205, e00061-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.T.; Anderson, T.F. Role of pili in bacterial conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 1970, 102, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, M.; Maddera, L.; Harris, R.L.; Silverman, P.M. F-pili dynamics by live-cell imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17978–17981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrenberger, M.B.; Villiger, W.; Bachi, T. Conjugational junctions: Morphology of specific contacts in conjugating Escherichia coli bacteria. J. Struct. Biol. 1991, 107, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozwandowicz, M.; Brouwer, M.S.M.; Fischer, J.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B.; Guerra, B.; Mevius, D.J.; Hordijk, J. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1121–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, L.; Garcia-Fernandez, A.; Fortini, D.; Carattoli, A. Replicon sequence typing of IncF plasmids carrying virulence and resistance determinants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 2518–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulenko, S.B.; Mobashery, S. Versatility of aminoglycosides and prospects for their future. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16, 430–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogios, P.J.; Cox, G.; Spanogiannopoulos, P.; Pillon, M.C.; Waglechner, N.; Skarina, T.; Koteva, K.; Guarné, A.; Savchenko, A.; Wright, G.D. Rifampin phosphotransferase is an unusual antibiotic resistance kinase. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Rodriguez-Martinez, J.M.; Mammeri, H.; Liard, A.; Nordmann, P. Origin of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinant QnrA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 3523–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sahm, D.F.; Jacoby, G.A.; Hooper, D.C. Emerging plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance associated with the qnr gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 1295–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piddock, L.J.V. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps-not just for resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunikis, I.; Denker, K.; Ostberg, Y.; Andersen, C.; Benz, R.; Bergström, S. An RND-type efflux system in Borrelia burgdorferi is involved in virulence and resistance to antimicrobial compounds. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirakata, Y.; Srikumar, R.; Poole, K.; Gotoh, N.; Suematsu, T.; Kohno, S.; Kamihira, S.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Speert, D.P. Multidrug efflux systems play an important role in the invasiveness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 196, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerse, A.E.; Sharma, N.D.; Simms, A.N.; Crow, E.T.; Snyder, L.A.; Shafer, W.M. A gonococcal efflux pump system enhances bacterial survival in a female mouse model of genital tract infection. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 5576–5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, K.; Latifi, T.; Groisman, E.A. Virulence and drug resistance roles of multidrug efflux systems of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 59, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckner, M.M.C.; Saw, H.T.H.; Osagie, R.N.; McNally, A.; Ricci, V.; Wand, M.E.; Woodford, N.; Ivens, A.; Webber, M.A.; Piddock, L.J.V. Clinically Relevant Plasmid-Host Interactions Indicate that Transcriptional and Not Genomic Modifications Ameliorate Fitness Costs of Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Carrying Plasmids. mBio 2018, 9, e02303-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimoto, K.; Tomita, H.; Fujimoto, S.; Okuzumi, K.; Ike, Y. Fluoroquinolone enhances the mutation frequency for meropenem-selected carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, but use of the high-potency drug doripenem inhibits mutant formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 3795–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgona, J.; Banerjee, T.; Anupurba, S. Role of efflux pumps inhibitor in decreasing antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae in a tertiary hospital in North India. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 9, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Jacoby, G.A. Updated functional classification of beta-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoesser, N.; Giess, A.; Batty, E.M.; Sheppard, A.E.; Walker, A.S.; Wilson, D.J.; Didelot, X.; Bashir, A.; Sebra, R.; Kasarskis, A.; et al. Genome sequencing of an extended series of NDM-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from neonatal infections in a Nepali hospital characterizes the extent of community- versus hospital-associated transmission in an endemic setting. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 7347–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deleo, F.R.; Chen, L.; Porcella, S.F.; Martens, C.A.; Kobayashi, S.D.; Porter, A.R.; Chavda, K.D.; Jacobs, M.R.; Mathema, B.; Olsen, R.J.; et al. Molecular dissection of the evolution of carbapenem-resistant multilocus sequence type 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4988–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, A.E.; Stoesser, N.; Wilson, D.J.; Sebra, R.; Kasarskis, A.; Anson, L.W.; Giess, A.; Pankhurst, L.J.; Vaughan, A.; Grim, C.J.; et al. Nested Russian Doll-Like Genetic Mobility Drives Rapid Dissemination of the Carbapenem Resistance Gene blaKPC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 3767–3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialek-Davenet, S.; Lavigne, J.P.; Guyot, K.; Mayer, N.; Tournebize, R.; Brisse, S.; Leflon-Guibout, V.; Nicolas-Chanoine, M.H. Differential contribution of AcrAB and OqxAB efflux pumps to multidrug resistance and virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.H.Y.; Chan, E.W.C.; Chen, S. Evolution and Dissemination of OqxAB-Like Efflux Pumps, an Emerging Quinolone Resistance Determinant among Members of Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 3290–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, A.; Hansen, L.H.; She, Q.X.; Sorensen, S.J. Nucleotide sequence of pOLA52: A conjugative IncX1 plasmid from Escherichia coli which enables biofilm formation and multidrug efflux. Plasmid 2008, 60, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liao, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, L.; Liu, B.; Yang, S.; Ma, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Spread of oqxAB in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium predominantly by IncHI2 plasmids. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 2263–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.T.; Yang, Q.E.; Li, L.; Sun, J.; Liao, X.P.; Fang, L.X.; Yang, S.S.; Deng, H.; Liu, Y.H. Dissemination and characterization of plasmids carrying oqxAB-blaCTX-M genes in Escherichia coli isolates from food-producing animals. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.Y.; Ning, J.A.; Sajid, A.; Cheng, G.Y.; Yuan, Z.H.; Hao, H.H. The nature and epidemiology of OqxAB, a multidrug efflux pump. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasdemir, U.O.; Chevalier, J.; Nordmann, P.; Pagès, J.M. Detection and prevalence of active drug efflux mechanism in various multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains from Turkey. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 2701–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzariol, A.; Zuliani, J.; Cornaglia, G.; Rossolini, G.M.; Fontana, R. AcrAB Efflux System: Expression and Contribution to Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Klebsiella spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 3984–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Cook, D.N.; Alberti, M.; Pon, N.G.; Nikaido, H.; Hearst, J.E. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1995, 16, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiders, T.; Amyes, S.G.; Levy, S.B. Role of AcrR and RamA in fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Singapore. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2831–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Z.; Chang, M.X.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Chen, P.X.; Jiang, H.X. Upregulation of AcrEF in Quinolone Resistance Development in Escherichia coli When AcrAB-TolC Function Is Impaired. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Datta, S.; Viswanathan, R.; Singh, A.K.; Basu, S. Tigecycline susceptibility in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli causing neonatal septicaemia (2007-10) and role of an efflux pump in tigecycline non-susceptibility. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialek-Davenet, S.; Marcon, E.; Leflon-Guibout, V.; Lavigne, J.P.; Bert, F.; Moreau, R.; Nicolas-Chanoine, M.H. In Vitro Selection of ramR and soxR Mutants Overexpressing Efflux Systems by Fluoroquinolones as Well as Cefoxitin in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 2795–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulyayangkul, P.; Wan Nur Ismah, W.A.K.; Douglas, E.J.A.; Avison, M.B. Mutation of kvrA Causes OmpK35 and OmpK36 Porin Downregulation and Reduced Meropenem-Vaborbactam Susceptibility in KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02208-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, M.; Miner, T.A.; Frederick, D.R.; Sepulveda, V.E.; Quinn, J.D.; Walker, K.A.; Miller, V.L. Identification of Two Regulators of Virulence That Are Conserved in Klebsiella pneumoniae Classical and Hypervirulent Strains. mBio 2018, 9, e01443-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, M.J.; Yakhnina, A.A.; Bernhardt, T.G. NlpD links cell wall remodeling and outer membrane invagination during cytokinesis in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, K.J.; Patel, S.; Wencewicz, T.A.; Dantas, G. The Tetracycline Destructases: A Novel Family of Tetracycline-Inactivating Enzymes. Chem. Biol. 2015, 22, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.X.; Chen, C.; Cui, C.Y.; Li, X.P.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, X.P.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.H. Emerging High-Level Tigecycline Resistance: Novel Tetracycline Destructases Spread via the Mobile Tet(X). Bioessays 2020, 42, e2000014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparrini, A.J.; Markley, J.L.; Kumar, H.; Wang, B.; Fang, L.; Irum, S.; Symister, C.T.; Wallace, M.; Burnham, C.D.; Andleeb, S.; et al. Tetracycline-inactivating enzymes from environmental, human commensal, and pathogenic bacteria cause broad-spectrum tetracycline resistance. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessler, A.T.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.M.; Schwarz, S. Mobile lincosamide resistance genes in staphylococci. Plasmid 2018, 99, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannatelli, A.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Giani, T.; Di Pilato, V.; Arena, F.; Ambretti, S.; Gaibani, P.; Rossolini, G.M. In vivo emergence of colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-type carbapenemases mediated by insertional inactivation of the PhoQ/PhoP mgrB regulator. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 5521–5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naparstek, L.; Carmeli, Y.; Navon-Venezia, S.; Banin, E. Biofilm formation and susceptibility to gentamicin and colistin of extremely drug-resistant KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czobor, I.; Novais, A.; Rodrigues, C.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Mihaescu, G.; Lazar, V.; Peixe, L. Efficient transmission of IncFIIY and IncL plasmids and Klebsiella pneumoniae ST101 clone producing OXA-48, NDM-1 or OXA-181 in Bucharest hospitals. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 48, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Bij, A.K.; Pitout, J.D. The role of international travel in the worldwide spread of multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2090–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, Y.; Murakami, M.; Suzuki, K.; Ito, H.; Wacharotayankun, R.; Ohsuka, S.; Kato, N.; Ohta, M. A novel integron-like element carrying the metallo-beta-lactamase gene blaIMP. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 1612–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docquier, J.D.; Riccio, M.L.; Mugnaioli, C.; Luzzaro, F.; Endimiani, A.; Toniolo, A.; Amicosante, G.; Rossolini, G.M. IMP-12, a new plasmid-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase from a Pseudomonas putida clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smet, A.; Van Nieuwerburgh, F.; Vandekerckhove, T.T.; Martel, A.; Deforce, D.; Butaye, P.; Haesebrouck, F. Complete nucleotide sequence of CTX-M-15-plasmids from clinical Escherichia coli isolates: Insertional events of transposons and insertion sequences. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, L.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P.; Carta, C.; Carattoli, A. Complete sequencing of an IncH plasmid carrying the blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-15 and qnrB1 genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 1645–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armin, S.; Fallah, F.; Karimi, A.; Karbasiyan, F.; Alebouyeh, M.; Rafiei Tabatabaei, S.; Rajabnejad, M.; Mansour Ghanaie, R.; Fahimzad, S.A.; Abdollahi, N.; et al. Antibiotic Susceptibility Patterns for Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Int. J. Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 8920977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakthavatchalam, Y.D.; Pragasam, A.K.; Biswas, I.; Veeraraghavan, B. Polymyxin susceptibility testing, interpretative breakpoints and resistance mechanisms: An update. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018, 12, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.R.; Lee, J.H.; Park, K.S.; Kim, Y.B.; Jeong, B.C.; Lee, S.H. Global Dissemination of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: Epidemiology, Genetic Context, Treatment Options, and Detection Methods. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Lokate, M.; Deurenberg, R.H.; Tepper, M.; Arends, J.P.; Raangs, E.G.; Lo-Ten-Foe, J.; Grundmann, H.; Rossen, J.W.; Friedrich, A.W. Use of whole-genome sequencing to trace, control and characterize the regional expansion of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing ST15 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Dong, G.; Cao, J.; Zhou, T. Chlorhexidine exposure of clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae strains leads to acquired resistance to this disinfectant and to colistin. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 53, 864–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.S.; Dwibedy, S.K.; Padhy, I. Polymyxins, the last-resort antibiotics: Mode of action, resistance emergence, and potential solutions. J. Biosci. 2021, 46, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jana, B.; Cain, A.K.; Doerrler, W.T.; Boinett, C.J.; Fookes, M.C.; Parkhill, J.; Guardabassi, L. The secondary resistome of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyres, K.L.; Holt, K.E. Klebsiella pneumoniae Population Genomics and Antimicrobial-Resistant Clones. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carattoli, A. Plasmids and the spread of resistance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013, 303, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Motta, S.; Aldana, M. Adaptive resistance to antibiotics in bacteria: A systems biology perspective. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2016, 8, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, K. Bacterial stress responses as determinants of antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2069–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, A.G. Stress Responses of Bacterial Cells as Mechanism of Development of Antibiotic Tolerance (Review). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2018, 54, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.S.; Zhang, R.K.; Liu, Z.H.; Li, B.Z.; Yuan, Y.J. Microbial Adaptation to Enhance Stress Tolerance. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 888746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, C.M.; Braxton, J.R.; Rodriguez-Osorio, C.A.; Zagieboylo, A.P.; Li, L.; Pironti, A.; Manson, A.L.; Nair, A.V.; Benson, M.; Cummins, K.; et al. Adaptive evolution of virulence and persistence in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, L.; Hancock, R.E. Adaptive and mutational resistance: Role of porins and efflux pumps in drug resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.B.; Singh, B.B.; Priyadarshi, N.; Chauhan, N.K.; Rajamohan, G. Role of novel multidrug efflux pump involved in drug resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauzy, A.; Ih, H.; Jacobs, M.; Marchand, S.; Grégoire, N.; Couet, W.; Buyck, J.M. Sequential Time-Kill, a Simple Experimental Trick To Discriminate between Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics Models with Distinct Heterogeneous Subpopulations versus Homogenous Population with Adaptive Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00788-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaleo, S.; Alvaro, A.; Nodari, R.; Panelli, S.; Bitar, I.; Comandatore, F. The red thread between methylation and mutation in bacterial antibiotic resistance: How third-generation sequencing can help to unravel this relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 957901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meletiadis, J.; Paranos, P.; Tsala, M.; Pournaras, S.; Vourli, S. Pharmacodynamics of colistin resistance in carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: The double-edged sword of heteroresistance and adaptive resistance. J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 71, 001565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzin, A.; Visalli, M.A.; Keeney, D.; Bradford, P.A. Influence of transcriptional activator RamA on expression of multidrug efflux pump AcrAB and tigecycline susceptibility in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Fu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Yu, W.; He, Y.; Ni, W.; Gao, Z. Proteomics Study of the Synergistic Killing of Tigecycline in Combination With Aminoglycosides Against Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 920761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, J.M.; Lopatkin, A.J.; Lobritz, M.A.; Collins, J.J. Bacterial Metabolism and Antibiotic Efficacy. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams-Sapper, S.; Gayoso, A.; Riley, L.W. Stress-Adaptive Responses Associated with High-Level Carbapenem Resistance in KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Pathog. 2018, 2018, 3028290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavio, M.M.; Vila, J.; Perilli, M.; Casanas, L.T.; Macia, L.; Amicosante, G.; Jimenez de Anta, M.T. Enhanced active efflux, repression of porin synthesis and development of Mar phenotype by diazepam in two enterobacteria strains. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 1119–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, S.J.; Connor, C.; McNally, A. The evolution and transmission of multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: The complexity of clones and plasmids. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 51, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, M.; Yuan, J.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, F.; Tian, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, B. The KbvR Regulator Contributes to Capsule Production, Outer Membrane Protein Biosynthesis, Antiphagocytosis, and Virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 2021, 89, e00016-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tian, Y.J.; Xu, L.; Zhang, F.S.; Lu, H.G.; Li, M.R.; Li, B. High Osmotic Stress Increases OmpK36 Expression through the Regulation of KbvR to Decrease the Antimicrobial Resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00507-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.B.; Rajamohan, G. KpnEF, a new member of the Klebsiella pneumoniae cell envelope stress response regulon, is an SMR-type efflux pump involved in broad-spectrum antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 4449–4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guan, J.; Chen, Z.; Tai, C.; Deng, Z.; Chao, Y.; Ou, H.Y. CpxR promotes the carbapenem antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae by directly regulating the expression and the dissemination of blaKPC on the IncFII conjugative plasmid. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2256427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ge, X. Discovering interrelated natural mutations of efflux pump KmrA from Klebsiella pneumoniae that confer increased multidrug resistance. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, e4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.; Raina, S. Regulated Assembly of LPS, Its Structural Alterations and Cellular Response to LPS Defects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Xiao, L.; He, H.; Zheng, D.; Li, X.; Yu, X.; Xu, N.; Hu, X.; et al. CusS-CusR Two-Component System Mediates Tigecycline Resistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.L.; Neu, H.M.; Alamneh, Y.A.; Reddinger, R.M.; Jacobs, A.C.; Singh, S.; Abu-Taleb, R.; Michel, S.L.J.; Zurawski, D.V.; Merrell, D.S. Characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii Copper Resistance Reveals a Role in Virulence. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, C.A.; Sutton, J.M.; Wand, M.E. Mutations in SilS and CusS/OmpC represent different routes to achieve high level silver ion tolerance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.S.; Suzuki, Y.; Jones, M.B.; Marshall, S.H.; Rudin, S.D.; van Duin, D.; Kaye, K.; Jacobs, M.R.; Bonomo, R.A.; Adams, M.D. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses of colistin-resistant clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae reveal multiple pathways of resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Lin, T.L.; Lin, Y.T.; Wang, J.T. Amino Acid Substitutions of CrrB Responsible for Resistance to Colistin through CrrC in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 3709–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Lin, T.L.; Lin, Y.T.; Wang, J.T. A putative RND-type efflux pump, H239_3064, contributes to colistin resistance through CrrB in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1509–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantel, L.; Juarez, P.; Serri, M.; Boucinha, L.; Lessoud, E.; Lanois, A.; Givaudan, A.; Racine, E.; Gualtieri, M. Missense Mutations in the CrrB Protein Mediate Odilorhabdin Derivative Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 65, e00139-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Cho, H.; Ko, K.S. Comparative analysis of the Colistin resistance-regulating gene cluster in Klebsiella species. J. Microbiol. 2022, 60, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConville, T.H.; Annavajhala, M.K.; Giddins, M.J.; Macesic, N.; Herrera, C.M.; Rozenberg, F.D.; Bhushan, G.L.; Ahn, D.; Mancia, F.; Trent, M.S.; et al. CrrB Positively Regulates High-Level Polymyxin Resistance and Virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.T.; Peng, H.L. Regulation of the homologous two-component systems KvgAS and KvhAS in Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. J. Biochem. 2006, 140, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ma, J.; Cheng, P.; Li, M.; Yu, Z.; Song, X.; Yu, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z. Roles of two-component regulatory systems in Klebsiella pneumoniae: Regulation of virulence, antibiotic resistance, and stress responses. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 272, 127374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, Y. EvgS/EvgA, the unorthodox two-component system regulating bacterial multiple resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0157723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, K.; Inazumi, Y.; Yamaguchi, A. Global analysis of genes regulated by EvgA of the two-component regulatory system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 2667–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.; Potel, C.M.; Tehrani, K.; Heck, A.J.R.; Martin, N.I.; Lemeer, S. A New Tool to Reveal Bacterial Signaling Mechanisms in Antibiotic Treatment and Resistance. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2018, 17, 2496–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Y.; Song, S.M. Structural Insights into the Lipopolysaccharide Transport (Lpt) System as a Novel Antibiotic Target. J. Microbiol. 2024, 62, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Guan, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Cokcetin, N.N.; Bottomley, A.L.; Robinson, A.; Harry, E.J.; van Oijen, A.M.; Su, Q.P.; Jin, D. Fast evolution of SOS-independent multi-drug resistance in bacteria. Elife 2025, 13, RP95058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynarcik, P.; Kolar, M. Detection of cell death markers as a tool for bacterial antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Epidemiol. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 65, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

| Target Drug Class | Antimicrobial Resistance Genes |

|---|---|

| Aminoglycoside | aac(3)-IIa, aac(3)-Ia, aac(3)-IId, aac(3)-IV, aac(6′)-33, aac(6′)-Iaf, aac(6′)-lb, aac(6′)-lb3, aac(6′)-lb4, aac(6′)-lb7, aac(6′)-lb-cr, aac(6′)-II, aac(6′)-IIa, aac(6′)-Iq, aadA, aadA1, aadA2, aadA5, aadA11, aadA16, aadA22, ant(2″)-Ia, aph(3′)-IIa, aph(3′)-VI, aph(3′)-VIb, armA, rmtB, rmtC, strA, strB |

| Beta-lactam | ESBLs: blaBEL-1, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, blaCTX-M-3, blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-24, blaCTX-M-27, blaCTX-M-55, blaCTX-M-62, blaCTX-M-63, blaCTX-M-65, blaCTX-M-71, blaCTX-M-104, blaCTX-M-125, blaKLUC-5, blaKPC-12, blaKPC-14, blaKPC-25, blaKPC-33, blaOXA-2, blaPER-1, blaPER-7, blaSFO-1, blaSHV-2a, blaSHV-5, blaSHV-7, blaSHV-12, blaSHV-30, blaVEB-1, blaVEB-3 Carbapenemases: blaBKC-1, blaGES-5, blaGIM(?), blaIMP-1, blaIMP-4, blaIMP-20, blaIMP-38, blaIMP-68, blaKPC-1, blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-4, blaKPC-41, blaNDM-1, blaNDM-3, blaNDM-4, blaNDM-5, blaNDM-6, blaNDM-7, blaNDM-19, blaOXA-48, blaOXA-181, blaOXA-204, blaOXA-232, blaOXA-244, blaSIM-1, blaVIM-1, blaVIM-4, blaVIM-27 AmpC: blaCMY-2, blaCMY-4, blaCMY-6, blaCMY-16, blaCMY-33, blaDHA-1, blaFOX-5, blaMOX-1, blaMOX-2 Other beta-lactamases: blaCARB-2, blaOXA-1, blaOXA-9, blaOXA-10, blaOXA-21, blaFONA-5, blaLAP-2, blaSCO-1, blaTEM-1, blaTEM-30, blaTEM-122, blaTEM-210 |

| Colistin | mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-8 |

| Fluoroquinolone | qepA2, qnrA1, qnrA3, qnrA6, qnrB1, qnrB2, qnrB4, qnrB6, qnrB9, qnrB17, qnrB19, qnrS1, qnrE2, |

| Fosfomycin | fosA3, fosA7 |

| MLS | ereA, ereA2, erm(42), ermB, ermT, lnuF, lnuG, mef(B), mphA, mphE, msrE, estT |

| Phenicol | catA1, catB2, catB3, catB4, catB11, catII, cmlA1, cmlA4, cmlA5, cmx, floR |

| Rifamycin | arr-2, arr-3 |

| Sulfonamide | sul1, sul2, sul3 |

| Tetracycline | tet(A), tet(B), tet(C), tet(D), tet(G), tetR |

| Tigecycline | tet(X4), tmexCD1-toprJ1 |

| Trimethoprim | dfrA1, dfrA5, dfrA7, dfrA8, dfrA12, dfrA14, dfrA15, dfrA16, dfrA17, dfrA23, dfrA25, dfrA27, dfrA30, dfrA35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zdarska, V.; Arcari, G.; Kolar, M.; Mlynarcik, P. Antibiotic Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Related Enterobacterales: Molecular Mechanisms, Mobile Elements, and Therapeutic Challenges. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010037

Zdarska V, Arcari G, Kolar M, Mlynarcik P. Antibiotic Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Related Enterobacterales: Molecular Mechanisms, Mobile Elements, and Therapeutic Challenges. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleZdarska, Veronika, Gabriele Arcari, Milan Kolar, and Patrik Mlynarcik. 2026. "Antibiotic Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Related Enterobacterales: Molecular Mechanisms, Mobile Elements, and Therapeutic Challenges" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010037

APA StyleZdarska, V., Arcari, G., Kolar, M., & Mlynarcik, P. (2026). Antibiotic Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Related Enterobacterales: Molecular Mechanisms, Mobile Elements, and Therapeutic Challenges. Antibiotics, 15(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010037