Smart Healing for Wound Repair: Emerging Multifunctional Strategies in Personalized Regenerative Medicine and Their Relevance to Orthopedics

Abstract

1. Introduction

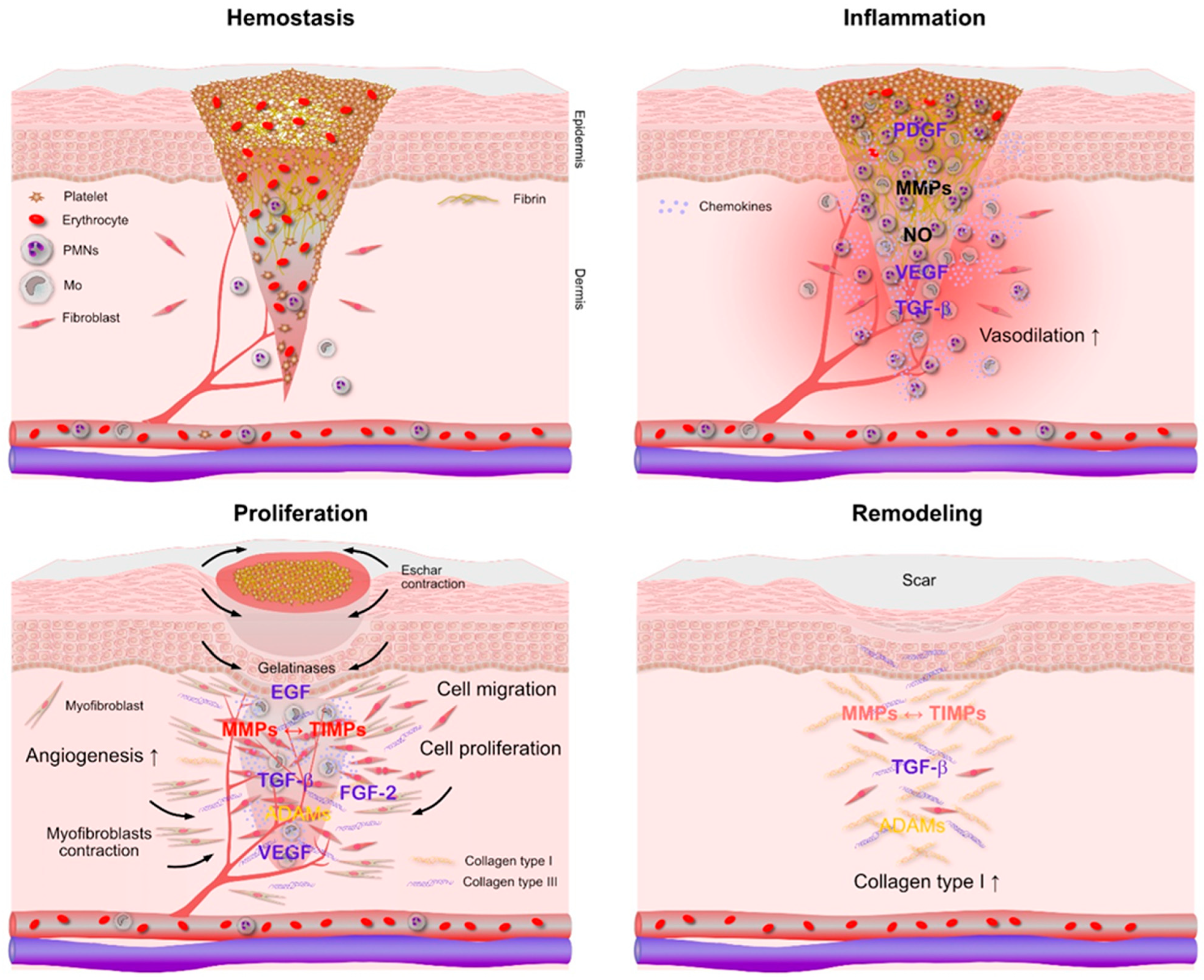

2. Molecular Complexity of Regeneration and Repair

3. Clinical Challenges in Orthopedics

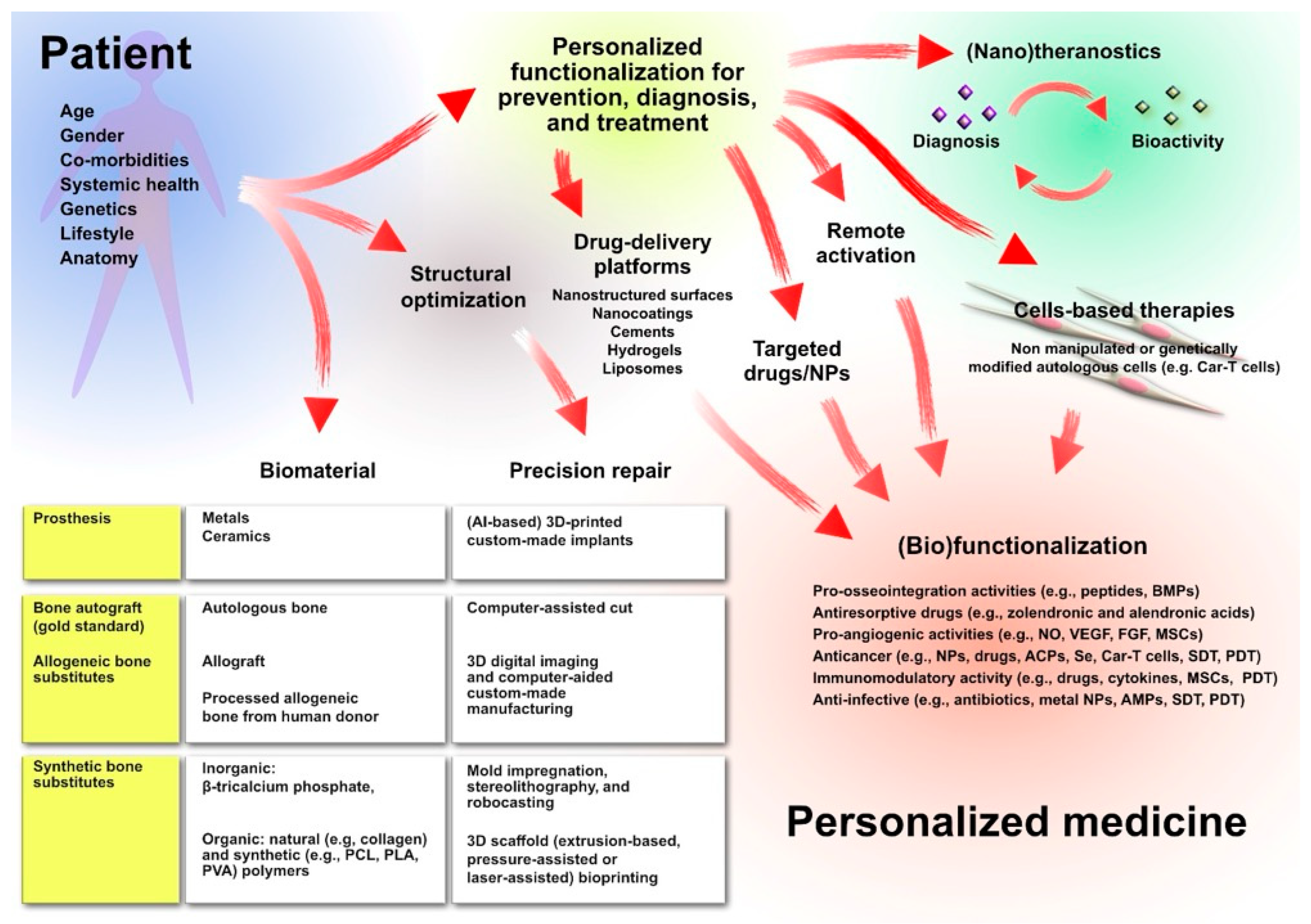

4. Multifunctional Scaffold-Based Therapeutic Strategies for Orthopedics Wound Healing

4.1. Chitosan as a Multifunctional Platform for Wound Healing

4.2. Ovine Forestomach Matrix (OFM): An Advanced Regenerative Approach for Chronic Wounds and Reconstructive Surgery

4.3. Hydrogels and Dressings Containing Platelet-Derived Growth Factors: A Biological Support for Tissue Repair

4.4. Glycosaminoglycan Mimetics in Regenerative Medicine

5. Strategies for Tissue Regeneration in Orthopedic Wound Healing

5.1. Innovative Carrier Systems for Controlled and Targeted Therapeutic Delivery in Regenerative Medicine

5.2. Advanced Biomaterials for Dermal Regeneration and Chronic Wound Management

5.3. Natural Extract-Loaded Nanofibers and Nanoparticles

5.4. Silk Fibroin-Based Platforms, DOPA-Inspired Adhesives and Nanodiamond–Silk Fibroin Composites

5.5. Functionalized Clay Membranes

5.6. Bioactive Agents Revisited Through Advanced Delivery Systems

6. Peptides-Based Strategies for Wound Healing

6.1. GHK-Cu Peptides and Their Regenerative Applications

6.2. Antimicrobial Peptides in Wound Healing: Infection Control and Tissue Regeneration

7. Integration of Smart Technologies in Wound Management

8. Other Significant Emerging Strategies

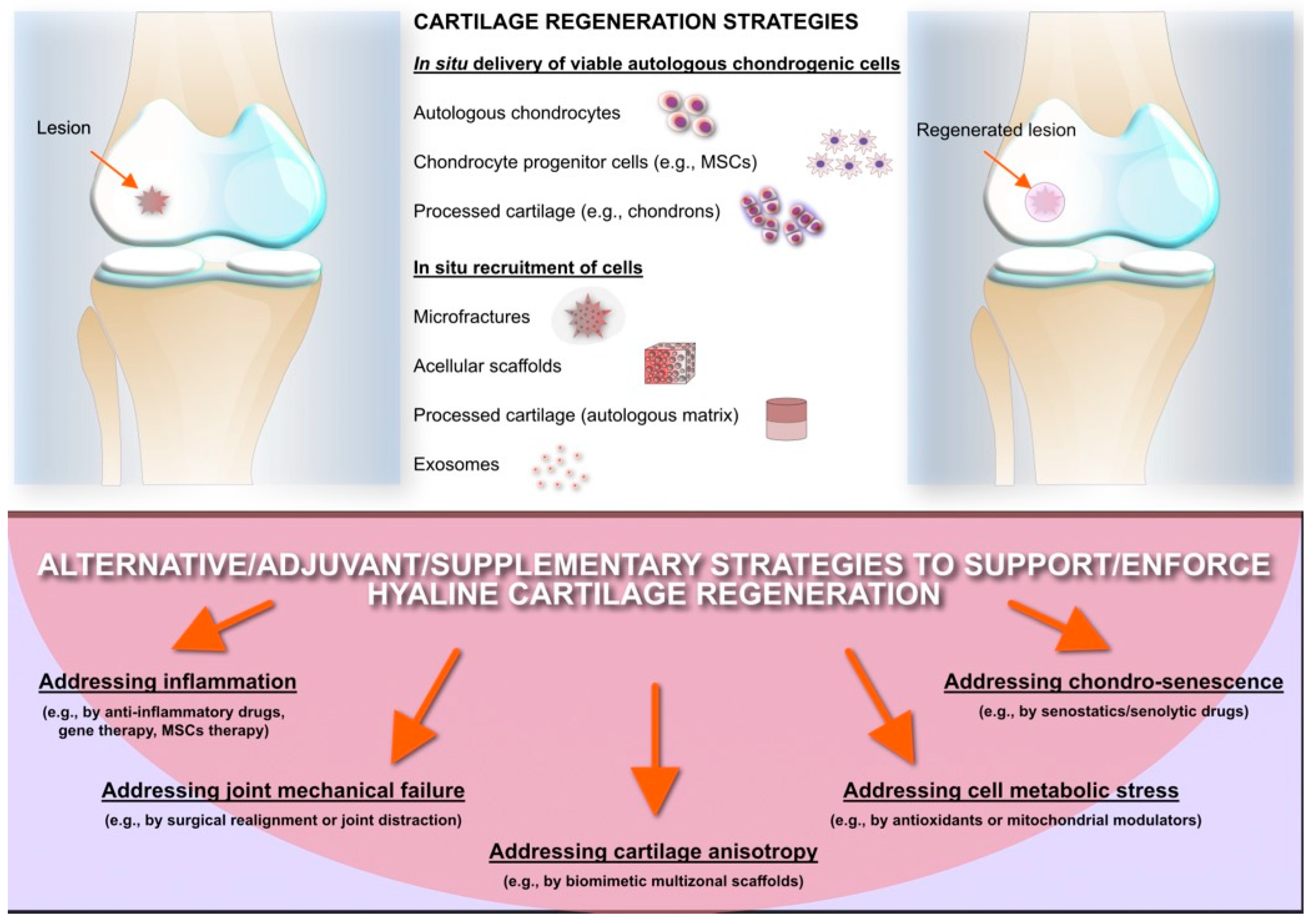

9. Articular Cartilage Regeneration: An Unresolved Challenge

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martinengo, L.; Olsson, M.; Bajpai, R.; Soljak, M.; Upton, Z.; Schmidtchen, A.; Car, J.; Jarbrink, K. Prevalence of chronic wounds in the general population: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, A.R.; Bernstein, J.M. Chronic wound infection: Facts and controversies. Clin. Dermatol. 2010, 28, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arciola, C.R.; Campoccia, D.; Montanaro, L. Implant infections: Adhesion, biofilm formation and immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.; Torres, M.; Bachar-Wikstrom, E.; Wikstrom, J.D. Cellular and molecular roles of reactive oxygen species in wound healing. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, X.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Feng, X. Effect of Diabetes on Wound Healing: A Bibliometrics and Visual Analysis. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 1275–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.M.; Shafikhani, S.H.; Soulika, A.M. Macrophage and Neutrophil Dysfunction in Diabetic Wounds. Adv. Wound Care 2024, 13, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIllhatton, A.; Lanting, S.; Chuter, V. The Effect of Overweight/Obesity on Cutaneous Microvascular Reactivity as Measured by Laser-Doppler Fluxmetry: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.P.; Sandepudi, K.; Shah, K.V.; Putnam, G.L.; Chintalapati, N.V.; Weissman, J.P.; Galiano, R.D. Evaluating the Effect of BMIs on Wound Complications After the Surgical Closure of Pressure Injuries. Surgeries 2025, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grada, A.; Phillips, T.J. Nutrition and cutaneous wound healing. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 40, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moores, J. Vitamin C: A wound healing perspective. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2013, 18, S6–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirloskar, K.M.; Dekker, P.K.; Kiene, J.; Zhou, S.; Bekeny, J.C.; Rogers, A.; Zolper, E.G.; Fan, K.L.; Evans, K.K.; Benedict, C.D.; et al. The Relationship Between Autoimmune Disease and Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs on Wound Healing. Adv. Wound Care 2022, 11, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, H.; Chaplin, S.; Holmes, T.; Moloney, M.A. Advanced wound therapies to promote healing in patients with severe peripheral arterial disease: Two case reports. J. Wound Care 2025, 34, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffetto, J.D.; Ligi, D.; Maniscalco, R.; Khalil, R.A.; Mannello, F. Why Venous Leg Ulcers Have Difficulty Healing: Overview on Pathophysiology, Clinical Consequences, and Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deptula, M.; Zielinski, J.; Wardowska, A.; Pikula, M. Wound healing complications in oncological patients: Perspectives for cellular therapy. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2019, 36, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.A.; Wynn, T.A.; Martin, P. Inflammation and metabolism in tissue repair and regeneration. Science 2017, 356, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, O.A.; Martin, P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of skin wound healing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Rojas-Quintero, J.; Wilder, J.; Tesfaigzi, Y.; Zhang, D.; Owen, C.A. Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-1 Promotes Polymorphonuclear Neutrophil (PMN) Pericellular Proteolysis by Anchoring Matrix Metalloproteinase-8 and -9 to PMN Surfaces. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 3267–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangogiannis, N. Transforming growth factor-beta in tissue fibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20190103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreca, A.P.; Pravata, V.M.; Markham, M.; Bonelli, S.; Murphy, G.; Nagase, H.; Troeberg, L.; Scilabra, S.D. TIMP-3 facilitates binding of target metalloproteinases to the endocytic receptor LRP-1 and promotes scavenging of MMP-1. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, K.; Xie, X.; Wang, S.; Gan, H.; Wang, X.; Wei, H. Macrophages as Multifaceted Orchestrators of Tissue Repair: Bridging Inflammation, Regeneration, and Therapeutic Innovation. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 8945–8959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhani Amit, J.K. Khatri Kavin Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Orthopaedic surgeries: A Complex issue and global threat. J. Orthop. Rep. 2025, 4, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyekwelu, I.; Yakkanti, R.; Protzer, L.; Pinkston, C.M.; Tucker, C.; Seligson, D. Surgical Wound Classification and Surgical Site Infections in the Orthopaedic Patient. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. Glob. Res. Rev. 2017, 1, e022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustilo, R.B.; Anderson, J.T. Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: Retrospective and prospective analyses. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1976, 58, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustilo, R.B.; Mendoza, R.M.; Williams, D.N. Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: A new classification of type III open fractures. J. Trauma 1984, 24, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovie, J.; Clement, N.D.; MacDonald, D.; Ahmed, I. Diabesity is associated with a worse joint specific functional outcome following primary total knee replacement. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2025, 145, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Liu, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhao, R.; Chen, W.; Yusufu, A.; Liu, Y. Diabetes mellitus impairs bone regeneration and biomechanics. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, A.; Qu, J.; Haynes, S.; Webb, B.G.; LaFontaine, J.; Rodrigues, D.C. Diabetes as a Risk Factor for Orthopedic Implant Surface Performance: A Retrieval and In Vitro Study. J. Bio Tribocorros 2021, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, S.M.; Linke, J.J.; Graef, F.; Foitzik, C.; Wichmann, M.G.; Weber, H.P. Stress and inflammation as a detrimental combination for peri-implant bone loss. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawi, J.; Tumanyan, K.; Tomas, K.; Misakyan, Y.; Gargaloyan, A.; Gonzalez, E.; Hammi, M.; Tomas, S.; Venketaraman, V. Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Pathophysiology, Immune Dysregulation, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.; Patel, D.; Rananavare, D.; Hudson, D.; Tran, M.; Schloss, R.; Langrana, N.; Berthiaume, F.; Kumar, S. Recent Advancements in Chitosan-Based Biomaterials for Wound Healing. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Luo, Y.; Ke, C.; Qiu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Hou, R.; Xu, L.; Wu, S. Chitosan-Based Functional Materials for Skin Wound Repair: Mechanisms and Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 650598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, D.; Getachew, E.; Mondal, A.K. Study on the Physicochemical Properties of Chitosan and their Applications in the Biomedical Sector. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 2023, 5025341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad-Bubulac, T.; Hamciuc, C.; Rimbu, C.M.; Aflori, M.; Butnaru, M.; Enache, A.A.; Serbezeanu, D. Fabrication of Poly(vinyl alcohol)/Chitosan Composite Films Strengthened with Titanium Dioxide and Polyphosphonate Additives for Packaging Applications. Gels 2022, 8, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobi, R.; Babu, R.S. In-vitro investigation of chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol/TiO(2) composite membranes for wound regeneration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 742, 151129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; He, C.; Dong, W.; Yang, X.; Kong, Q.; Yan, B.; He, J. Quaternized chitosan-based biomimetic nanozyme hydrogels with ROS scavenging, oxygen generating, and antibacterial capabilities for diabetic wound repair. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Dai, Z.; Huang, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, X.; Que, X.; Shi, R.; Zhou, J.; Dong, J.; et al. A temperature-sensitive chitosan hydrogels loaded with nano-zinc oxide and exosomes from human umbilical vein endothelial cells accelerates wound healing. Regen. Ther. 2025, 30, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, W.; Xie, G.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, B.; Wang, Q.; Xu, K.; Bao, J. An improved osseointegration of metal implants by pitavastatin loaded multilayer films with osteogenic and angiogenic properties. Biomaterials 2022, 280, 121260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Gu, L. A two-phase and long-lasting multi-antibacterial coating enables titanium biomaterials to prevent implants-related infections. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 15, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburn, R.; Chaffin, A.E.; Bosque, B.A.; Frampton, C.; Dempsey, S.G.; Young, D.A.; May, B.C.H.; Bohn, G.A.; Melin, M.M. Clinical Efficacy of Ovine Forestomach Matrix and Collagen/Oxidised Regenerated Cellulose for the Treatment of Venous Leg Ulcers: A Retrospective Comparative Real-World Evidence Study. Int. Wound J. 2025, 22, e70368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormican, M.T.; Creel, N.J.; Bosque, B.A.; Dowling, S.G.; Rideout, P.P.; Vassy, W.M. Ovine Forestomach Matrix in the Surgical Management of Complex Volumetric Soft Tissue Defects: A Retrospective Pilot Case Series. Eplasty 2023, 23, e66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lawlor, J.; Bosque, B.A.; Frampton, C.; Young, D.A.; Martyka, P. Limb Salvage via Surgical Soft-tissue Reconstruction with Ovine Forestomach Matrix Grafts: A Prospective Study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2024, 12, e6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosque, B.A.; Dowling, S.G.; May, B.C.H.; Kaufman, R.; Zilberman, I.; Zolfaghari, N.; Que, H.; Longobardi, J.; Skurka, J.; Geiger, J.E.; et al. Ovine Forestomach Matrix in the Surgical Management of Complex Lower-Extremity Soft-Tissue Defects. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2023, 113, 22–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, R.; Pan, R.; He, L.; Dai, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, S.; Li, B.; Li, Y. Decellularized Extracellular Matrices for Skin Wound Treatment. Materials 2025, 18, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.J.; Dempsey, S.G.; Veale, R.W.; Duston-Fursman, C.G.; Rayner, C.A.F.; Javanapong, C.; Gerneke, D.; Dowling, S.G.; Bosque, B.A.; Karnik, T.; et al. Further structural characterization of ovine forestomach matrix and multi-layered extracellular matrix composites for soft tissue repair. J. Biomater. Appl. 2022, 36, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, M.; Bozorgi, M.; Rezakhani, L.; Bozorgi, A. Fabrication and characterization of nanohydroxyapatite/chitosan/decellularized placenta scaffold for bone tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Su, Y.; Yang, J.; Ma, H.; Fang, H.; Zhu, J.; Du, J.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Kang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; et al. A 3D bioprinted gelatin/quaternized chitosan/decellularized extracellular matrix based hybrid bionic scaffold with multifunctionality for infected full-thickness skin wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 309, 142816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kim, K.W.; Kurian, A.G.; Jain, S.K.; Bhattacharya, S.; Singh, R.K.; Kim, H.W. Advanced therapeutic scaffolds of biomimetic periosteum for functional bone regeneration. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Garcia, N.; Loh, Y.S.; Marks, D.C.; Banakh, I.; Jagadeesan, P.; Cameron, N.R.; Yung-Chih, C.; Costa, M.; Peter, K.; et al. A platelet-derived hydrogel improves neovascularisation in full thickness wounds. Acta Biomater. 2021, 136, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.A.; Jenkins, B.J. Recent insights into targeting the IL-6 cytokine family in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Du, P.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Guo, P.; Diao, L.; Lu, G. Mesenchymal stromal cells pretreated with proinflammatory cytokines enhance skin wound healing via IL-6-dependent M2 polarization. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Salehi, S.; Tavakoli, M.; Mirhaj, M.; Varshosaz, J.; Kazemi, N.; Salehi, S.; Mehrjoo, M.; Abadi, S.A.M. PDGF and VEGF-releasing bi-layer wound dressing made of sodium tripolyphosphate crosslinked gelatin-sponge layer and a carrageenan nanofiber layer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateiwa, D.; Kaito, T. Advances in bone regeneration with growth factors for spinal fusion: A literature review. N. Am. Spine Soc. J. 2023, 13, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, W.F.; Peckham, S.M.; Badura, J.M. A comprehensive clinical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (INFUSE Bone Graft). Int. Orthop. 2007, 31, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, S.; Bennet, S.J.; Arora, M. Bone morphogenetic protein-7: Review of signalling and efficacy in fracture healing. J. Orthop. Translat. 2016, 4, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillman, C.E.; Jayasuriya, A.C. FDA-approved bone grafts and bone graft substitute devices in bone regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 130, 112466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambhia, K.J.; Sun, H.; Feng, K.; Kannan, R.; Doleyres, Y.; Holzwarth, J.M.; Doepker, M.; Franceschi, R.T.; Ma, P.X. Nanofibrous 3D scaffolds capable of individually controlled BMP and FGF release for the regulation of bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2024, 190, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yin, S.; Shi, J.; Yang, G.; Wen, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, X. Orchestration of energy metabolism and osteogenesis by Mg(2+) facilitates low-dose BMP-2-driven regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 18, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, J.A.; Fulton, T.M.; Sangadala, S.; Kaiser, J.; Devereaux, E.J.; Oliver, C.; Presciutti, S.M.; Boden, S.D.; Willett, N.J. Local FK506 delivery induces osteogenesis in in vivo rat bone defect and rabbit spine fusion models. Bone 2024, 187, 117195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Liu, L.; Lam, R.W.M.; Toh, S.Y.; Abbah, S.A.; Wang, M.; Ramruttun, A.K.; Bhakoo, K.; Cool, S.; Li, J.; et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells with low dose bone morphogenetic protein 2 enhances scaffold-based spinal fusion in a porcine model. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2022, 16, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trubert-Paneli, A.; Williams, J.A.; Windmill, J.F.C.; Iturriaga, L.; Pringle, E.W.; Rogkoti, T.; Dong, S.; Cipitria, A.; Miller, A.F.; Gonzalez-Garcia, C.; et al. Tenascin-c functionalised self-assembling peptide hydrogels for critical-sized bone defect reconstruction. Biomaterials 2026, 325, 123553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClendon, M.T.; Ji, W.; Greene, A.C.; Sai, H.; Sangji, M.H.; Sather, N.A.; Chen, C.H.; Lee, S.S.; Katchko, K.; Jeong, S.S.; et al. A supramolecular polymer-collagen microparticle slurry for bone regeneration with minimal growth factor. Biomaterials 2023, 302, 122357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Li, C.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, F.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. A functional chitosan-based hydrogel as a wound dressing and drug delivery system in the treatment of wound healing. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 7533–7549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, N.; Janghu, P.; Pasrija, R.; Umesh, M.; Chakraborty, P.; Sarojini, S.; Thomas, J. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan nanofibers for wound healing and drug delivery application. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 87, 104858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Luo, Y. Chitosan-based nanocarriers for encapsulation and delivery of curcumin: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 179, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.Y.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.J.; Xiao, Z.C.; He, C.C.; Shi, H.X.; Li, X.K.; Yang, S.L.; Xiao, J. Research Advances in Tissue Engineering Materials for Sustained Release of Growth Factors. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 808202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, M.; Chen, S.; You, J.; Li, Y.; Lv, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y. 3D-printed biomimetic bone scaffold loaded with lyophilized concentrated growth factors promotes bone defect repair by regulation the VEGFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazetyte-Godiene, A.; Vailionyte, A.; Jelinskas, T.; Denkovskij, J.; Usas, A. Promotion of hMDSC differentiation by combined action of scaffold material and TGF-beta superfamily growth factors. Regen. Ther. 2024, 27, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansevoort, M.; Wentholt, S.; Li Vecchi, G.; de Vries, M.; Versteeg, E.M.M.; Boekema, B.; Choppin, A.; Barritault, D.; Chiappini, F.; van Kuppevelt, T.H.; et al. Next-Generation Biomaterials for Wound Healing: Development and Evaluation of Collagen Scaffolds Functionalized with a Heparan Sulfate Mimic and Fibroblast Growth Factor 2. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansevoort, M.; Oostendorp, C.; Bouwman, L.F.; Tiemessen, D.M.; Geutjes, P.J.; Feitz, W.F.J.; van Kuppevelt, T.H.; Daamen, W.F. Collagen-Heparin-FGF2-VEGF Scaffolds Induce a Regenerative Gene Expression Profile in a Fetal Sheep Wound Model. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2024, 21, 1173–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, T.; Aarthy, M.; Sundarapandiyan, A.; Ayyadurai, N. Bioengineered Silk Fibroin Hydrogel Reinforced with Collagen-Like Protein Chimeras for Improved Wound Healing. Macromol. Biosci. 2025, 25, e2400346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Golland, B.; Tronci, G.; Thornton, P.D. A redox-responsive hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel for chronic wound management. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 7494–7501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, H.; Heydari, M.; Khodaei, M. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis methods and applications in wound healing. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 23, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, K.; Ding, H.; Long, M.; Zhu, X.; Lou, X.; Li, Y.; Gu, N. Prussian Blue Nanozyme-Functionalized Hydrogel with Self-Enhanced Redox Regulation for Accelerated Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 36511–36520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Qiao, L.; Xu, H.; Guo, B. pH/Glucose Dual Responsive Metformin Release Hydrogel Dressings with Adhesion and Self-Healing via Dual-Dynamic Bonding for Athletic Diabetic Foot Wound Healing. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 3194–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.L.; Yen, C.E.; Hsu, W.C.; Yeh, M.L. Incorporation of cerium oxide nanoparticles into the micro-arc oxidation layer promotes bone formation and achieves structural integrity in magnesium orthopedic implants. Acta Biomater. 2025, 191, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antezana, P.E.; Municoy, S.; Ostapchuk, G.; Catalano, P.N.; Hardy, J.G.; Evelson, P.A.; Orive, G.; Desimone, M.F. 4D Printing: The Development of Responsive Materials Using 3D-Printing Technology. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mageed, H.M.; AbuelEzz, N.Z.; Ali, A.A.; Abdelaziz, A.E.; Nada, D.; Abdelraouf, S.M.; Fouad, S.A.; Bishr, A.; Radwan, R.A. Newly designed curcumin-loaded hybrid nanoparticles: A multifunctional strategy for combating oxidative stress, inflammation, and infections to accelerate wound healing and tissue regeneration. BMC Biotechnol. 2025, 25, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partovi, A.; Khedrinia, M.; Arjmand, S.; Ranaei Siadat, S.O. Electrospun nanofibrous wound dressings with enhanced efficiency through carbon quantum dots and citrate incorporation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, S.; Peng, J.; Chang, R. Electrospun Nanofibers from Plant Natural Products: A New Approach Toward Efficient Wound Healing. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 13973–13990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X. Sprayable Berberine-Silk Fibroin Microspheres with Extracellular Matrix Anchoring Function Accelerate Infected Wound Healing through Antibacterial and Anti-inflammatory Effects. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 3643–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Qiu, H.; Niu, W.; Li, X.; Qian, J. A hyaluronic acid/silk fibroin/poly-dopamine-coated biomimetic hydrogel scaffold with incorporated neurotrophin-3 for spinal cord injury repair. Acta Biomater. 2023, 167, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; He, Y.; Ma, L.; Lu, L.; Cai, J.; Xu, Z.; Shuai, Y.; Wan, Q.; Wang, J.; Mao, C.; et al. Regenerated silk fibroin coating stable liquid metal nanoparticles enhance photothermal antimicrobial activity of hydrogel for wound infection repair. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Bai, D.; Abraham, A.N.; Jadhav, A.; Linklater, D.; Matusica, A.; Nguyen, D.; Murdoch, B.J.; Zakhartchouk, N.; Dekiwadia, C.; et al. Electrospun Nanodiamond-Silk Fibroin Membranes: A Multifunctional Platform for Biosensing and Wound-Healing Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 48408–48419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, S.; Wu, Y.; Chug, M.K.; Brisbois, E.J.; Kim, K.; Mukhopadhyay, K. Engineered Zwitterion-Infused Clay Composites with Antibacterial and Antifungal Efficacy. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.15645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherednichenko, K.; Kopitsyn, D.; Batasheva, S.; Fakhrullin, R. Probing Antimicrobial Halloysite/Biopolymer Composites with Electron Microscopy: Advantages and Limitations. Polymers 2021, 13, 3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Hu, B.; Zhang, X.; Fan, P.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S. Recent advances in the application of clay-containing hydrogels for hemostasis and wound healing. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2024, 21, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmani, S.A.; Koc, S.; Erkut, T.S.; Gumusderelioglu, M. Polymer-clay nanofibrous wound dressing materials containing different boron compounds. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 83, 127408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajisnik, D.; Uskokovic-Markovic, S.; Dakovic, A. Chitosan-Clay Mineral Nanocomposites with Antibacterial Activity for Biomedical Application: Advantages and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.T.; Huang, L.D.; Liu, K.; Pang, K.F.; Tang, H.; Li, T.; Huang, Y.P.; Zhang, W.Q.; Wang, J.J.; Yin, G.L.; et al. Nano-Biomimetic Fibronectin/Lysostaphin-Co-Loaded Silk Fibroin Dressing Accelerates Full-Thickness Wound Healing via ECM-Mimicking Microarchitecture and Dual-Function Modulation. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 7469–7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilian, A.I.; Lim, C.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.H.; Mahardika, I.H.; Yoo, S.H.; Jo, Y.; Jeong, H.; Ju, B.G.; Burpo, F.J.; et al. Translational Extracellular Matrix Spray-Coating Approach for Large-Scale Bioactive Surface Functionalization and Tissue Repair. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e02804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaragi, E.; Sakamoto, M.; Katayama, Y.; Kawabata, S.; Somamoto, S.; Noda, K.; Morimoto, N. A prospective multicenter phase III clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of silk elastin sponge in patients with skin defects. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Chen, F.; Chen, Z. Elastin-like polypeptide and triclosan-modified PCL membrane provides aseptic protection in tissue regeneration. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 33, 101968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arciola, C.R.; Radin, L.; Alvergna, P.; Cenni, E.; Pizzoferrato, A. Heparin surface treatment of poly(methylmethacrylate) alters adhesion of a Staphylococcus aureus strain: Utility of bacterial fatty acid analysis. Biomaterials 1993, 14, 1161–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adil, F.; Memon, M.A.; Khan, F.A.A.; Awan, A.; Siddiqui, S.U.; Piprani, F.Z.; Zareen, K. Efficacy of topical heparin spray on donor site wound healing after split thickness skin grafting. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Yin, Z.; Shi, X.; Zhao, R.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y. Electrospun Scaffold Co-Modified with YIGSR Peptide and Heparin for Enhanced Skin Wound Healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2501745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, I.; Joshi, V.; Kuddushi, M.; Zhang, X.H.; Kumar, S.; Aswal, V.K.; Raje, N.H.; Malek, N. Bio-MOF-Polymeric Hybrid Wound Healing Patch for Enhanced Transdermal Codelivery of Curcumin and Heparin. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2025, 3, 1819–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, J.; Khan, S. Composite HPMC-Gelatin Films Loaded with Cameroonian and Manuka Honeys Show Antibacterial and Functional Wound Dressing Properties. Gels 2025, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, G.E.; Gousios, G.; Cremers, N.A.J.; Peters, L.J.F. Treating Infected Non-Healing Venous Leg Ulcers with Medical-Grade Honey: A Prospective Case Series. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servin de la Mora-Lopez, D.; Olivera-Castillo, L.; Lopez-Cervantes, J.; Sanchez-Machado, D.I.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Soto-Valdez, H.; Madera-Santana, T.J. Bioengineered Chitosan-Collagen-Honey Sponges: Physicochemical, Antibacterial, and In Vitro Healing Properties for Enhanced Wound Healing and Infection Control. Polymers 2025, 17, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, C.; Giron-Hernandez, J.; Honey, D.A.; Fox, E.M.; Cassa, M.A.; Tonda-Turo, C.; Camagnola, I.; Gentile, P. Synergistic nanocoating with layer-by-layer functionalized PCL membranes enhanced by manuka honey and essential oils for advanced wound healing. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, S.; Younes, N.; Abunasser, S.; Tamimi, F.; Nasrallah, G. Silver-based dressings for the prevention of surgical site infections: Evidence from randomized trials. J. Hosp. Infect. 2025, 162, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapmanee, S.; Bhubhanil, S.; Khongkow, M.; Namdee, K.; Yingmema, W.; Bhummaphan, N.; Wongchitrat, P.; Charoenphon, N.; Hutchison, J.A.; Talodthaisong, C.; et al. Application of Gelatin/Vanillin/Fe(3+)/AGP-AgNPs Hydrogels Promotes Wound Contraction, Enhances Dermal Growth Factor Expression, and Minimizes Skin Irritation. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 10530–10545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Bilal, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Tripeptides Ghk and GhkCu-modified silver nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial and wound healing activities. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2024, 236, 113785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, R.; Deng, C.; Li, P.; Tang, Y.; Hou, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Tu, J.; Jiang, X.; et al. Dimeric copper peptide incorporated hydrogel for promoting diabetic wound healing. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoccia, D.; Bottau, G.; De Donno, A.; Bua, G.; Ravaioli, S.; Capponi, E.; Sotgiu, G.; Bellotti, C.; Costantini, S.; Arciola, C.R. Assessing Cytotoxicity, Proteolytic Stability, and Selectivity of Antimicrobial Peptides: Implications for Orthopedic Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melichercik, P.; Nesuta, O.; Cerovsky, V. Antimicrobial Peptides for Topical Treatment of Osteomyelitis and Implant-Related Infections: Study in the Spongy Bone. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Chen, F.; Yao, Y.; Wu, C.; Ye, S.; Ma, Z.; Yuan, H.; Shao, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Bioactive mesoporous silica nanoparticle-functionalized titanium implants with controllable antimicrobial peptide release potentiate the regulation of inflammation and osseointegration. Biomaterials 2024, 305, 122465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaveti, R.; Jakus, M.A.; Chen, H.; Jain, B.; Kennedy, D.G.; Caso, E.A.; Mishra, N.; Sharma, N.; Uzunoglu, B.E.; Han, W.B.; et al. Water-powered, electronics-free dressings that electrically stimulate wounds for rapid wound closure. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Hu, Z. Bioelectronic sutures with electrochemical glucose-sensing for real-time wound monitoring. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1370, 344320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, Z. Self-powered biosensing sutures for real-time wound monitoring. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 259, 116365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Jin, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, L.; Lin, H.; Chen, H. Smart bandages for wound monitoring and treatment. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 283, 117522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protzman, N.M.; Mao, Y.; Long, D.; Sivalenka, R.; Gosiewska, A.; Hariri, R.J.; Brigido, S.A. Placental-Derived Biomaterials and Their Application to Wound Healing: A Review. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costela-Ruiz, V.J.; Melguizo-Rodriguez, L.; Bellotti, C.; Illescas-Montes, R.; Stanco, D.; Arciola, C.R.; Lucarelli, E. Different Sources of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Tissue Regeneration: A Guide to Identifying the Most Favorable One in Orthopedics and Dentistry Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, P.; Kannaiyan, J.; Rajabathar, J.R.; Paulpandian, P.; Kamatchi, R.K.; Paulraj, B.; Al-Lohedan, H.A.; Arokiyaraj, S.; Veeramani, V. Isolation, Expansion, and Characterization of Placenta Originated Decidua Basalis-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 35538–35547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Vizely, K.; Li, C.Y.; Shen, K.; Shakeri, A.; Khosravi, R.; Smith, J.R.; Alteza, E.; Zhao, Y.; Radisic, M. Biomaterials for immunomodulation in wound healing. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbae032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eerdekens, H.; Pirlet, E.; Willems, S.; Bronckaers, A.; Pincela Lins, P.M. Extracellular vesicles: Innovative cell-free solutions for wound repair. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1571461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, C. Advances in 3D printing technology for preparing bone tissue engineering scaffolds from biodegradable materials. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1483547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsky, N.A.; Ehlen, Q.T.; Greenfield, J.A.; Antonietti, M.; Slavin, B.V.; Nayak, V.V.; Pelaez, D.; Tse, D.T.; Witek, L.; Daunert, S.; et al. Three-Dimensional Bioprinting: A Comprehensive Review for Applications in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishal, S.; Phaugat, P.; Devi, R.; Garg, V.; Kumar, V.; Chopra, H.; Aggarwal, N. Harnessing 3D printing in bone tissue engineering. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaabani, E.; Sharifiaghdam, M.; Faridi-Majidi, R.; De Smedt, S.C.; Braeckmans, K.; Fraire, J.C. Gene therapy to enhance angiogenesis in chronic wounds. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 29, 871–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X. New Perspectives and Prospects of microRNA Delivery in Diabetic Wound Healing. Mol. Pharmacol. 2024, 106, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, D.; Zhao, D.; Sivaraj, D.; Trotsyuk, A.; Bonham, C.A.; Fischer, K.S.; Kehl, T.; Fehlmann, T.; Greco, A.H.; Kussie, H.C.; et al. Cas9-mediated knockout of Ndrg2 enhances the regenerative potential of dendritic cells for wound healing. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.Y.; Cao, M.Q.; Xu, T.Y. Progress in the application of artificial intelligence in skin wound assessment and prediction of healing time. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 2765–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.; Li, W.; Shi, W.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, J. Modeling epithelial wound closure dynamics with AI: A comparative study across cell types. Regen. Ther. 2025, 30, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, R.; Zhou, H.; Shi, Z.; Huang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Construction of a deep learning-based predictive model to evaluate the influence of mechanical stretching stimuli on MMP-2 gene expression levels in fibroblasts. Biomed. Eng. Online 2025, 24, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.A.; Hamilton, E.J.; Russell, D.A.; Game, F.; Wang, S.C.; Baptista, S.; Monteiro-Soares, M. Diabetic Foot Ulcer Classification Models Using Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Techniques: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e69408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Liu, H.; Yuan, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, R.; Wang, M.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, M.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Conductive Hydrogel Dressings for Refractory Wounds Monitoring. Nanomicro Lett. 2025, 17, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, V.R.; Yao, M.; Miller, C.J. Noncontact low-frequency ultrasound therapy in the treatment of chronic wounds: A meta-analysis. Wound Repair Regen. 2011, 19, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Yang, C.; Aimaiti, A.; Wang, F.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Cao, L. Effective treatment using a single-stage revision with non-contact low frequency ultrasonic debridement in the treatment of periprosthetic joint infection: A prospective single-arm study. Bone Jt. J. 2025, 107, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Escobar, S.; Garcia-Alvarez, Y.; Alvaro-Afonso, F.J.; Lopez-Moral, M.; Garcia-Madrid, M.; Lazaro-Martinez, J.L. Clinical Effects of Weekly and Biweekly Low-Frequency Ultrasound Debridement Versus Standard of Wound Care in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pueyo Moliner, A.; Ito, K.; Zaucke, F.; Kelly, D.J.; de Ruijter, M.; Malda, J. Restoring articular cartilage: Insights from structure, composition and development. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2025, 21, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotna, R.; Frankova, J. Materials Suitable for Osteochondral Regeneration. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 30097–30108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Oliver, B.G.; Wang, B.; Li, H.; Yong, K.T.; Li, J.J. Biomimetic multizonal scaffolds for the reconstruction of zonal articular cartilage in chondral and osteochondral defects. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 43, 510–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthu, S.; Korpershoek, J.V.; Novais, E.J.; Tawy, G.F.; Hollander, A.P.; Martin, I. Failure of cartilage regeneration: Emerging hypotheses and related therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2023, 19, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Kerr, D.t.; Zheng, M.; Seyler, T. Chondrocyte Invasion May Be a Mechanism for Persistent Staphylococcus Aureus Infection In Vitro. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2024, 482, 1839–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoccia, D.; Montanaro, L.; Ravaioli, S.; Cangini, I.; Testoni, F.; Visai, L.; Arciola, C.R. New Parameters to Quantitatively Express the Invasiveness of Bacterial Strains from Implant-Related Orthopaedic Infections into Osteoblast Cells. Materials 2018, 11, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Therapeutic Strategy | Key Advantages and Disadvantages | Primary Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Bio-Scaffolds (Chitosan, Silk Fibroin, OFM, ODM, 3D Bioprinting) | Structural and environmental support: Provides native 3D architecture (osteoconduction for ODM), mimics ECM (OFM) and enables precise spatial control of cells; but high cost, complex fabrication, potential immunogenicity. | Soft tissue reconstruction, bone defects, limb salvage, tendon exposure (OFM), bone regeneration (ODM), and complex anatomical reconstruction. |

| Bioactive Factors and Peptides (PDGFs, BMPs, GHK-Cu, AMPs, GAG Mimetics) | Signaling and protection: stimulation of angiogenesis and matrix synthesis, antimicrobial activity (membrane disruption), redox modulation, and protection of growth factors from enzymatic degradation; but short half-life, stability issues, risk of off-target effects. | Non-union fractures, infected biofilm-associated wounds, and chronic diabetic ulcers. |

| Cellular and Gene Therapies (MSCs, Placental derivatives, Exosomes, CRISPR) | Paracrine and genetic modulation: Secretion of regenerative cargo (EVs, cytokines), immunomodulation (macrophage polarization), and targeted correction of molecular defects; but high cost, potential tumorigenicity or immune reactions. | Complex regenerative deficits, immune-privileged healing contexts, and personalized regenerative strategies. |

| Smart Technologies and Nanomaterials (Sensors, Bioelectric Dressings, Cerium/MnO2 NPs) | Responsive monitoring and stimulation: Real-time sensing (pH/Temp), electrical stimulation of repair processes and stimuli-responsive antioxidant activity; but complex design, potential cytotoxicity, scalability challenges. | Diabetic foot management, theranostic (therapy + diagnostic) approaches, and oxidative stress reduction in chronic wounds. |

| Inorganic & Hybrid Systems (Functionalized Clays, Ag/Curcumin-loaded Nanofibers) | Delivery & Stability: High absorption capacity, sustained release of antimicrobial ions or natural compounds, and broad-spectrum infection control; but potential cytotoxicity, limited biodegradability, burst release risk. | Infected wounds in resource-limited settings and in the management of highly exudative wounds. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arciola, C.R.; Panichi, V.; Bua, G.; Costantini, S.; Bottau, G.; Ravaioli, S.; Capponi, E.; Campoccia, D. Smart Healing for Wound Repair: Emerging Multifunctional Strategies in Personalized Regenerative Medicine and Their Relevance to Orthopedics. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010036

Arciola CR, Panichi V, Bua G, Costantini S, Bottau G, Ravaioli S, Capponi E, Campoccia D. Smart Healing for Wound Repair: Emerging Multifunctional Strategies in Personalized Regenerative Medicine and Their Relevance to Orthopedics. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleArciola, Carla Renata, Veronica Panichi, Gloria Bua, Silvia Costantini, Giulia Bottau, Stefano Ravaioli, Eleonora Capponi, and Davide Campoccia. 2026. "Smart Healing for Wound Repair: Emerging Multifunctional Strategies in Personalized Regenerative Medicine and Their Relevance to Orthopedics" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010036

APA StyleArciola, C. R., Panichi, V., Bua, G., Costantini, S., Bottau, G., Ravaioli, S., Capponi, E., & Campoccia, D. (2026). Smart Healing for Wound Repair: Emerging Multifunctional Strategies in Personalized Regenerative Medicine and Their Relevance to Orthopedics. Antibiotics, 15(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010036