Leveraging Different Distance Functions to Predict Antiviral Peptides with Geometric Deep Learning from ESMFold-Predicted Tertiary Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Analysis of the Inter-Amino Acid Distance Distributions

2.2. Analysis of the Graph Representations Built with Different Distance Functions

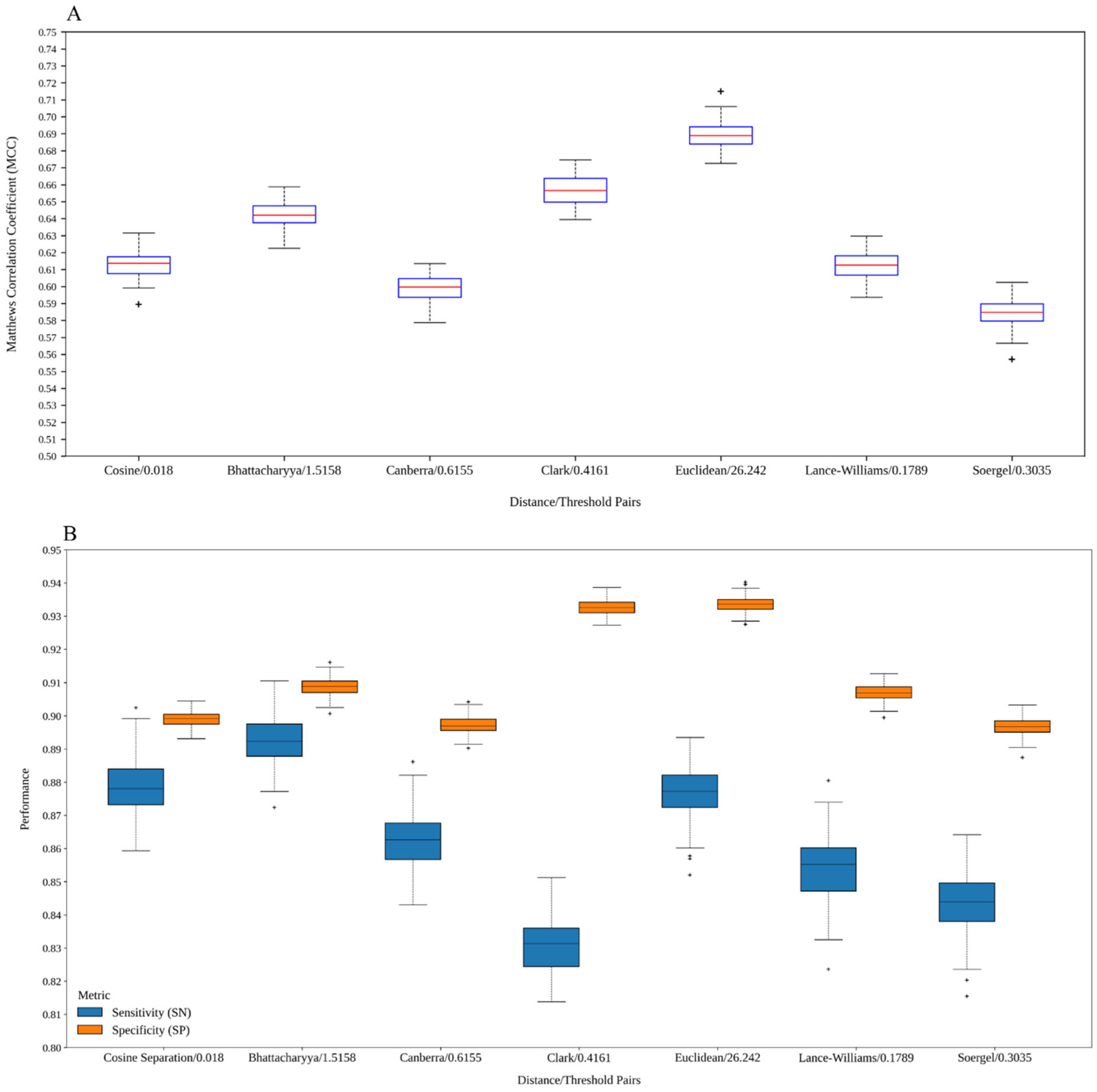

2.3. Analysis of the Models Built with Graphs Derived from Different Distance Functions

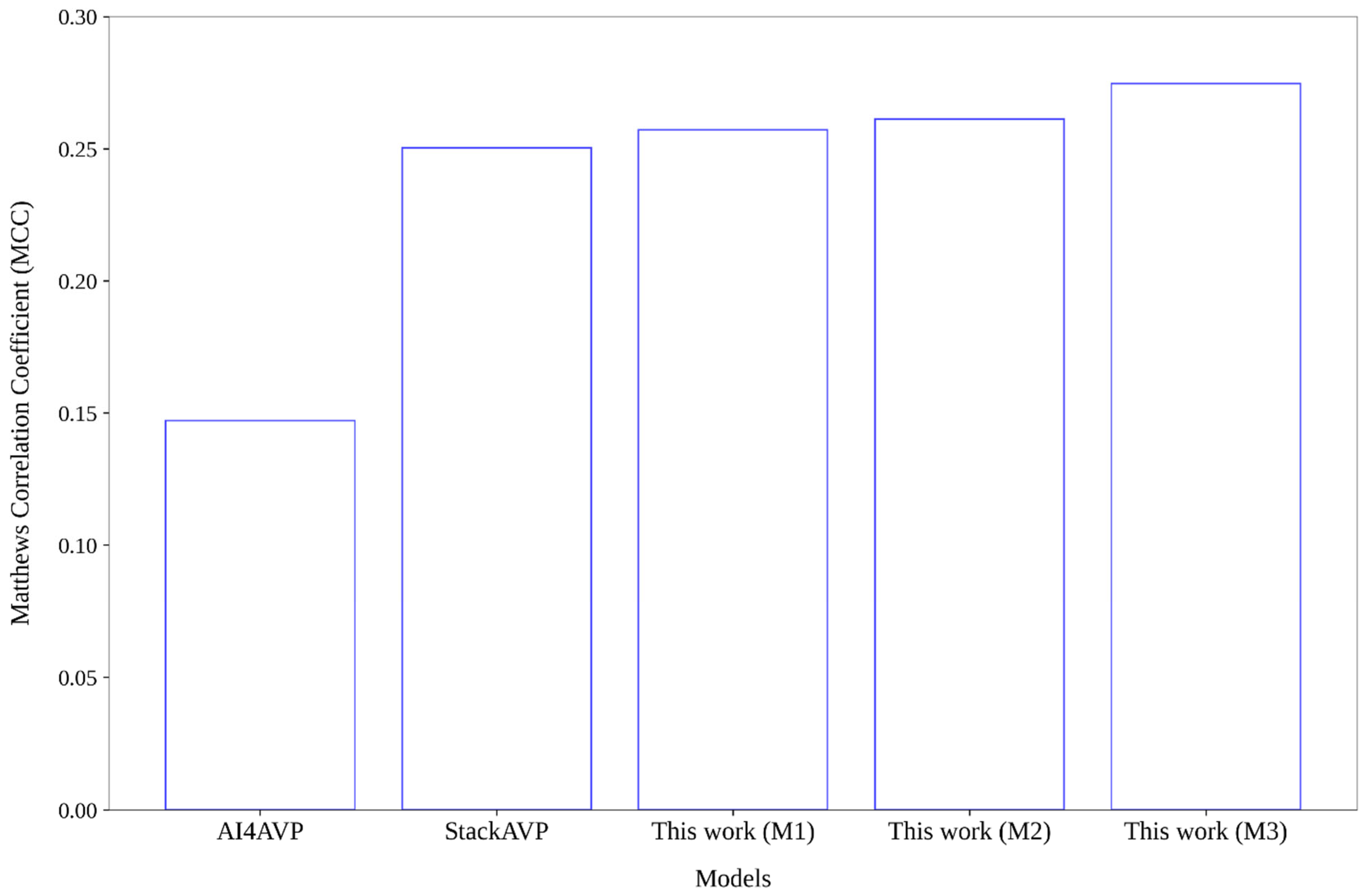

2.4. Comparative Analysis Regarding Models Reported in the Literature

2.5. Analysis of the Codified Chemical Space According to the Dissimilarity of the Predictions

3. Conclusions

4. Future Outlooks

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Overview of the Esm-AxP-GDL Framework

5.2. Peptide Datasets

5.3. Perplexity of the ESMFold-Predicted Peptide Structures

5.4. Generation of Random Graphs and Similarity Calculation Between Graph Pairs

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, M.W. Introduction: A Short History of Virology. In Viruses and Man: A History of Interactions; Taylor, M.W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh, N.D.; Ladner, J.T.; Lemey, P.; Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E.C.; Andersen, K.G. Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. History of Ebola Disease Outbreaks. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ebola/outbreaks/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Huremović, D. Brief history of pandemics (pandemics throughout history). In Psychiatry of Pandemics: A Mental Health Response to Infection Outbreak; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Prasad, R.; Balasubramanian, V.; Gupta, N. Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis and HIV Infection: Current Perspectives. HIV/AIDS-Res. Palliat. Care 2020, 12, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.C.; Hurt, A.C.; Dobbie, Z.; Clinch, B.; Oxford, J.S.; Piedra, P.A. Understanding the Impact of Resistance to Influenza Antivirals. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34, e00224-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalkwijk, H.H.; Snoeck, R.; Andrei, G. Acyclovir resistance in herpes simplex viruses: Prevalence and therapeutic alternatives. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 206, 115322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.-Y.; Milde, J.; Ham, Y.; Ramos Calderón, J.P.; Wedde, M.; Dürrwald, R.; Duwe, S.C. Preparing for the Next Influenza Season: Monitoring the Emergence and Spread of Antiviral Resistance. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, C.S.; Chibale, K.; Goss, R.J.M.; Jaspars, M.; Newman, D.J.; Dorrington, R.A. Antiviral drug discovery: Preparing for the next pandemic. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 3647–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas Boas, L.C.P.; Campos, M.L.; Berlanda, R.L.A.; de Carvalho Neves, N.; Franco, O.L. Antiviral peptides as promising therapeutic drugs. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 3525–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Siman-Tov, G.; Hall, G.; Bhalla, N.; Narayanan, A. Human antimicrobial peptides as therapeutics for viral infections. Viruses 2019, 11, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, C.B.; Gill, D. Antiviral Activities of Human Host Defense Peptides. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 1420–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, G.; Gabrani, R. Antiviral Peptides: Identification and Validation. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2021, 27, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N.; Qureshi, A.; Kumar, M. AVPpred: Collection and prediction of highly effective antiviral peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W199–W204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meher, P.K.; Sahu, T.K.; Saini, V.; Rao, A.R. Predicting antimicrobial peptides with improved accuracy by incorporating the compositional, physico-chemical and structural features into Chou’s general PseAAC. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaduangrat, N.; Nantasenamat, C.; Prachayasittikul, V.; Shoombuatong, W. Meta-iAVP: A Sequence-Based Meta-Predictor for Improving the Prediction of Antiviral Peptides Using Effective Feature Representation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pu, Y.; Tang, J.; Zou, Q.; Guo, F. DeepAVP: A Dual-Channel Deep Neural Network for Identifying Variable-Length Antiviral Peptides. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 3012–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinacho-Castellanos, S.A.; García-Jacas, C.R.; Gilson, M.K.; Brizuela, C.A. Alignment-free antimicrobial peptide predictors: Improving performance by a thorough analysis of the largest available data set. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3141–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, P.B.; Hewage, C.M. ENNAVIA is a novel method which employs neural networks for antiviral and anti-coronavirus activity prediction for therapeutic peptides. Brief. Bioinf. 2021, 22, bbab258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Yao, L.; Jhong, J.-H.; Wang, Z.; Lee, T.-Y. AVPIden: A new scheme for identification and functional prediction of antiviral peptides based on machine learning approaches. Brief. Bioinf. 2021, 22, bbab263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Shrivastava, S.; Singh, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, A.K.; Saxena, S. Deep-AVPpred: Artificial Intelligence Driven Discovery of Peptide Drugs for Viral Infections. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2022, 26, 5067–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Qian, W.; Ma, N.; Liu, W.; Yang, Z. Datt-AVP: Antiviral Peptide Prediction by Sequence-Based Dual Channel Network with Attention Mechanism. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf. 2025, 22, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenkwan, P.; Chumnanpuen, P.; Schaduangrat, N.; Shoombuatong, W. Stack-AVP: A Stacked Ensemble Predictor Based on Multi-view Information for Fast and Accurate Discovery of Antiviral Peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437, 168853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Shen, Y.; Tang, X.; Wen, J.; Song, Y.; Wei, M.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, X. AVPpred-BWR: Antiviral peptides prediction via biological words representation. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, R.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, L.; Luo, X.; Zou, Q.; Lv, Z. iAVP-RFVOT: Identify Antiviral Peptides by Random Forest Voting Machine Learning with Unified Manifold Learning Embedded Features. Biochemistry 2025, 64, 3137–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durairaj, J.; de Ridder, D.; van Dijk, A.D.J. Beyond sequence: Structure-based machine learning. Comp. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Su, H.; Wang, W.; Ye, L.; Wei, H.; Peng, Z.; Anishchenko, I.; Baker, D.; Yang, J. The trRosetta server for fast and accurate protein structure prediction. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 5634–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.; DiMaio, F.; Anishchenko, I.; Dauparas, J.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Lee, G.R.; Wang, J.; Cong, Q.; Kinch, L.N.; Schaeffer, R.D.; et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science 2021, 373, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Akin, H.; Rao, R.; Hie, B.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, W.; Smetanin, N.; Verkuil, R.; Kabeli, O.; Shmueli, Y.; et al. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science 2023, 379, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, L.; He, J.; Lin, D.; Xiang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, X.; Wu, H.; Li, H.; et al. A method for multiple-sequence-alignment-free protein structure prediction using a protein language model. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, E.F.; Jones, T.; Plate, L.; Meiler, J.; Gulsevin, A. Benchmarking AlphaFold2 on peptide structure prediction. Structure 2023, 31, 111–119.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Bertoni, D.; Magana, P.; Paramval, U.; Pidruchna, I.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Tsenkov, M.; Nair, S.; Mirdita, M.; Yeo, J.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: Providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D368–D375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta Platforms, I. ESM Metagenomic Atlas. 2023. Available online: https://esmatlas.com/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Yan, K.; Lv, H.; Guo, Y.; Peng, W.; Liu, B. sAMPpred-GAT: Prediction of antimicrobial peptide by graph attention network and predicted peptide structure. Bioinformatics 2022, 39, btac715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordoves-Delgado, G.; García-Jacas, C.R. Predicting Antimicrobial Peptides Using ESMFold-Predicted Structures and ESM-2-Based Amino Acid Features with Graph Deep Learning. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 4310–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Qiu, J.; Xiang, D.; Jiao, P.; Cao, Y.; Xu, Q.; Qiao, D.; Xu, H.; Cao, Y. deepAMPNet: A novel antimicrobial peptide predictor employing AlphaFold2 predicted structures and a bi-directional long short-term memory protein language model. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielezinski, A.; Vinga, S.; Almeida, J.; Karlowski, W.M. Alignment-free sequence comparison: Benefits, applications, and tools. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, R.; Consonni, V. Handbook of Molecular Descriptors, 1st ed.; Mannhold, R., Kubinyi, H., Folkers, G., Eds.; Methods and Principles in Medicinal Chemistry; WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009; Volume 11, p. 667. [Google Scholar]

- Fasoulis, R.; Paliouras, G.; Kavraki, L.E. Graph representation learning for structural proteomics. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2021, 5, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorijević, V.; Renfrew, P.D.; Kosciolek, T.; Leman, J.K.; Berenberg, D.; Vatanen, T.; Chandler, C.; Taylor, B.C.; Fisk, I.M.; Vlamakis, H.; et al. Structure-based protein function prediction using graph convolutional networks. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamasb, A.; Viñas Torné, R.; Ma, E.; Du, Y.; Harris, C.; Huang, K.; Hall, D.; Lió, P.; Blundell, T. Graphein-a python library for geometric deep learning and network analysis on biomolecular structures and interaction networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 27153–27167. [Google Scholar]

- Baranwal, M.; Magner, A.; Saldinger, J.; Turali-Emre, E.S.; Elvati, P.; Kozarekar, S.; VanEpps, J.S.; Kotov, N.A.; Violi, A.; Hero, A.O. Struct2Graph: A graph attention network for structure based predictions of protein–protein interactions. BMC Bioinf. 2022, 23, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réau, M.; Renaud, N.; Xue, L.C.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J. DeepRank-GNN: A graph neural network framework to learn patterns in protein–protein interfaces. Bioinformatics 2022, 39, btac759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, X.; Li, L.; Zhao, P.; Yang, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, J. Hierarchical graph learning for protein–protein interaction. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero-Ponce, Y.; García-Jacas, C.R.; Barigye, S.J.; Valdés-Martiní, J.R.; Rivera-Borroto, O.M.; Pino-Urias, R.W.; Cubillán, N.; Alvarado, Y.J. Optimum Search Strategies or Novel 3D Molecular Descriptors: Is there a Stalemate? Curr. Bioinf. 2015, 10, 533–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deza, M.M.; Deza, E. Encyclopedia of Distances, 4th ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera-Mendoza, L.; Ayala-Ruano, S.; Martinez-Rios, F.; Chavez, E.; García-Jacas, C.R.; Brizuela, C.A.; Marrero-Ponce, Y. StarPep Toolbox: An open-source software to assist chemical space analysis of bioactive peptides and their functions using complex networks. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala-Ruano, S.; Marrero-Ponce, Y.; Aguilera-Mendoza, L.; Pérez, N.; Agüero-Chapin, G.; Antunes, A.; Aguilar, A.C. Network Science and Group Fusion Similarity-Based Searching to Explore the Chemical Space of Antiparasitic Peptides. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 46012–46036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agüero-Chapin, G.; Antunes, A.; Mora, J.R.; Pérez, N.; Contreras-Torres, E.; Valdes-Martini, J.R.; Martinez-Rios, F.; Zambrano, C.H.; Marrero-Ponce, Y. Complex Networks Analyses of Antibiofilm Peptides: An Emerging Tool for Next-Generation Antimicrobials’ Discovery. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Mendieta, K.; Agüero-Chapin, G.; Marquez, E.A.; Perez-Castillo, Y.; Barigye, S.J.; Vispo, N.S.; García-Jacas, C.R.; Marrero-Ponce, Y. Peptide hemolytic activity analysis using visual data mining of similarity-based complex networks. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2024, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Jacas, C.R.; García-González, L.A.; Martinez-Rios, F.; Tapia-Contreras, I.P.; Brizuela, C.A. Handcrafted versus non-handcrafted (self-supervised) features for the classification of antimicrobial peptides: Complementary or redundant? Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Jacas, C.R.; Pinacho-Castellanos, S.A.; García-González, L.A.; Brizuela, C.A. Do deep learning models make a difference in the identification of antimicrobial peptides? Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac094. [Google Scholar]

- Veltri, D.; Kamath, U.; Shehu, A. Deep learning improves antimicrobial peptide recognition. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2740–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Karnik, S.; Nilawe, P.; Jayaraman, V.K.; Idicula-Thomas, S. ClassAMP: A prediction tool for classification of antimicrobial peptides. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf. 2012, 9, 1535–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, P.; Lin, W.-Z.; Jia, J.-H.; Chou, K.-C. iAMP-2L: A two-level multi-label classifier for identifying antimicrobial peptides and their functional types. Anal. Biochem. 2013, 436, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Xu, D. Imbalanced multi-label learning for identifying antimicrobial peptides and their functional types. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3745–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.-R.; Kuo, T.-R.; Wu, L.-C.; Lee, T.-Y.; Horng, J.-T. Characterization and identification of antimicrobial peptides with different functional activities. Brief. Bioinf. 2019, 21, 1098–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Zhou, C.; Su, R.; Zou, Q. PEPred-Suite: Improved and robust prediction of therapeutic peptides using adaptive feature representation learning. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4272–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuncheva, L.I.; Whitaker, C.J. Measures of Diversity in Classifier Ensembles and Their Relationship with the Ensemble Accuracy. Mach. Learn. 2003, 51, 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-T.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Wang, C.-T.; Cheng, W.-C.; Lu, I.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, S.-H. AI4AVP: An antiviral peptides predictor in deep learning approach with generative adversarial network data augmentation. Bioinform. Adv. 2022, 2, vbac080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Mendoza, L.; Marrero-Ponce, Y.; Beltran, J.A.; Tellez Ibarra, R.; Guillen-Ramirez, H.A.; Brizuela, C.A. Graph-based data integration from bioactive peptide databases of pharmaceutical interest: Toward an organized collection enabling visual network analysis. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4739–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabere, M.N.; Noble, W.S. Empirical comparison of web-based antimicrobial peptide prediction tools. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 1921–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrent, M.; Andreu, D.; Nogués, V.M.; Boix, E. Connecting Peptide Physicochemical and Antimicrobial Properties by a Rational Prediction Model. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Guan, J.; Xie, P.; Chung, C.-R.; Zhao, Z.; Dong, D.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Deng, J.; Pang, Y.; et al. dbAMP 3.0: Updated resource of antimicrobial activity and structural annotation of peptides in the post-pandemic era. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D364–D376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdos, P.; Rényi, A. On the evolution of random graphs. Publ. Math. Inst. Hung. Acad. Sci. 1960, 5, 17–60. [Google Scholar]

- NetworkX. NetworkX Is a Python Package for the Creation, Manipulation, and Study of the Structure, Dynamics, and Functions of Complex Networks. 2024. Available online: https://networkx.org/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Wilson, R.C.; Zhu, P. A study of graph spectra for comparing graphs and trees. Pattern Recognit. 2008, 41, 2833–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gera, R.; Alonso, L.; Crawford, B.; House, J.; Mendez-Bermudez, J.A.; Knuth, T.; Miller, R. Identifying network structure similarity using spectral graph theory. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2018, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Distance Functions | Min | Q1 a | Q2 b | Average | Std. Dev. | Q3 c | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euclidean | 0.7188 | 10.2836 | 16.6132 | 20.1265 | 13.6897 | 26.2420 | 254.0563 | 1.5428 | 3.9371 |

| Bhattacharyya | 0.0912 | 1.5158 | 2.4304 | 2.7378 | 1.6204 | 3.6452 | 20.3574 | 1.0430 | 1.3395 |

| Cosine | 2.8148E-09 | 0.0180 | 0.0654 | 0.1310 | 0.1644 | 0.1799 | 1.0000 | 1.9995 | 4.2676 |

| Lance–Williams | 0.0057 | 0.1789 | 0.3041 | 0.3398 | 0.2039 | 0.4660 | 1.0000 | 0.7500 | 0.0418 |

| Soergel | 0.0113 | 0.3035 | 0.4664 | 0.4746 | 0.2174 | 0.6357 | 1.0000 | 0.1714 | −0.7705 |

| Canberra | 0.0125 | 0.6155 | 1.0142 | 1.0855 | 0.5971 | 1.4712 | 3.0000 | 0.5885 | −0.1419 |

| Clark | 0.0101 | 0.4161 | 0.6813 | 0.7075 | 0.3612 | 0.9830 | 1.7321 | 0.3124 | −0.6337 |

| Model | SN | SP | ACC | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) AVPDiscover original test set (12,001 sequences) | ||||

| This work (Cosine/0.018) | 0.8821 | 0.8972 | 0.8957 | 0.6117 |

| This work (Bhattacharyya/1.5158) | 0.9008 | 0.9086 | 0.9078 | 0.6471 |

| This work (Canberra/0.6155) | 0.8667 | 0.8958 | 0.8928 | 0.5990 |

| This work (Clark/0.4161) | 0.8341 | 0.9287 | 0.9190 | 0.6489 |

| This work (Euclidean/26.242) | 0.8764 | 0.9304 | 0.9248 | 0.6810 |

| This work (Lance–Williams/0.1789) | 0.8496 | 0.9048 | 0.8992 | 0.6056 |

| This work (Soergel/0.3035) | 0.8382 | 0.8971 | 0.8911 | 0.5828 |

| ProtDCal-AV_RF (see Table 2 in [18]) | 0.7420 | 0.8730 | 0.8600 | 0.4760 |

| ESM-1b based Random Forest model—see Table 2 in [52] | 0.9210 | 0.8680 | 0.8730 | 0.5850 |

| AMPScanner (retrained)—see Table S4 in [53] | 0.6293 | 0.8759 | 0.8560 | 0.4024 |

| (B) AVPDiscover reduced test set (11,460 sequences) | ||||

| This work (Cosine/0.018) | 0.8665 | 0.8965 | 0.8947 | 0.5088 |

| This work (Bhattacharyya/1.5158) | 0.8621 | 0.9099 | 0.9071 | 0.5346 |

| This work (Canberra/0.6155) | 0.8433 | 0.8959 | 0.8928 | 0.4941 |

| This work (Clark/0.4161) | 0.8113 | 0.9339 | 0.9265 | 0.5641 |

| This work (Euclidean/26.242) | 0.8389 | 0.9353 | 0.9295 | 0.5853 |

| This work (Lance–Williams/0.1789) | 0.8389 | 0.9017 | 0.8979 | 0.5031 |

| This work (Soergel/0.3035) | 0.8331 | 0.9002 | 0.8962 | 0.4966 |

| ProtDCal-AV_RF (see Table 5 in [18]) | 0.7270 | 0.8730 | 0.8640 | 0.3860 |

| ClassAMP-SVM [55] | 0.2510 | 0.8300 | 0.7950 | 0.0510 |

| iAMP-2L [56] | 0.1510 | 0.9990 | 0.9490 | 0.3690 |

| MLAMP [57] | 0.0900 | 0.9990 | 0.9450 | 0.2720 |

| AMPfun [58] | 0.2600 | 0.5430 | 0.5260 | −0.0940 |

| PEPred-suite [59] | 0.2120 | 0.5150 | 0.4970 | −0.1300 |

| iAMPpred [15] | 0.8040 | 0.8570 | 0.8540 | 0.4060 |

| Meta-iAVP [16] | 0.6650 | 0.5680 | 0.5730 | 0.1110 |

| Stack-AVP [23] | 0.9478 | 0.8567 | 0.8622 | 0.4859 |

| (C) AVPDiscover reduced test set w/o Stack-AVP training sequences (11,095 sequences) | ||||

| This work (Cosine/0.018) | 0.8673 | 0.8965 | 0.8956 | 0.3878 |

| This work (Bhattacharyya/1.5158) | 0.8796 | 0.9099 | 0.9091 | 0.4197 |

| This work (Canberra/0.6155) | 0.8642 | 0.8959 | 0.8950 | 0.3853 |

| This work (Clark/0.4161) | 0.8241 | 0.9339 | 0.9307 | 0.4499 |

| This work (Euclidean/26.242) | 0.8302 | 0.9353 | 0.9322 | 0.4572 |

| This work (Lance–Williams/0.1789) | 0.8488 | 0.9017 | 0.9001 | 0.3885 |

| This work (Soergel/0.3035) | 0.8395 | 0.9002 | 0.8984 | 0.3813 |

| Stack-AVP [23] | 0.8889 | 0.8567 | 0.8577 | 0.3382 |

| Distance/Threshold Pairs | SN | SP | ACC | MCC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Euclidean distance threshold-derived graph-free combined models | |||||

| Cosine/0.018 | Bhattacharyya/1.5158 | 0.8301 | 0.9673 | 0.9533 | 0.7598 |

| Canberra/0.6155 | 0.8252 | 0.9536 | 0.9404 | 0.7112 | |

| Soergel/0.3035 | 0.7976 | 0.9610 | 0.9443 | 0.7165 | |

| Bhattacharyya/1.5158 | Canberra/0.6155 | 0.8236 | 0.9671 | 0.9524 | 0.7549 |

| Lance–Williams/0.1789 | 0.8098 | 0.9668 | 0.9507 | 0.7444 | |

| Soergel/0.3035 | 0.8000 | 0.9645 | 0.9477 | 0.7301 | |

| Canberra/0.6155 | Soergel/0.3035 | 0.7951 | 0.9582 | 0.9415 | 0.7057 |

| Lance–Williams/0.1789 | Soergel/0.3035 | 0.7886 | 0.9589 | 0.9414 | 0.7034 |

| (B) Euclidean distance threshold-derived graph-dependent combined models | |||||

| Euclidean/26.242 | Cosine/0.018 | 0.8228 | 0.9689 | 0.9539 | 0.7606 |

| Clark/0.4161 | 0.7902 | 0.9783 | 0.9590 | 0.7753 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cordoves-Delgado, G.; García-Jacas, C.R.; Marrero-Ponce, Y.; Aguila, S.A.; Lizama-Uc, G. Leveraging Different Distance Functions to Predict Antiviral Peptides with Geometric Deep Learning from ESMFold-Predicted Tertiary Structures. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010039

Cordoves-Delgado G, García-Jacas CR, Marrero-Ponce Y, Aguila SA, Lizama-Uc G. Leveraging Different Distance Functions to Predict Antiviral Peptides with Geometric Deep Learning from ESMFold-Predicted Tertiary Structures. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleCordoves-Delgado, Greneter, César R. García-Jacas, Yovani Marrero-Ponce, Sergio A. Aguila, and Gabriel Lizama-Uc. 2026. "Leveraging Different Distance Functions to Predict Antiviral Peptides with Geometric Deep Learning from ESMFold-Predicted Tertiary Structures" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010039

APA StyleCordoves-Delgado, G., García-Jacas, C. R., Marrero-Ponce, Y., Aguila, S. A., & Lizama-Uc, G. (2026). Leveraging Different Distance Functions to Predict Antiviral Peptides with Geometric Deep Learning from ESMFold-Predicted Tertiary Structures. Antibiotics, 15(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010039