Duration Matters: Tailoring Antibiotic Therapy for Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Guideline Recommendations on Antibiotic Duration

3. Clinical Evidence from Trials and Meta-Analyses

3.1. Randomized Controlled Trials

3.2. Meta-Analysis

3.3. Further Studies

4. Biomarkers and Diagnostic Stewardship for Guiding Duration

- The PRORATA trial [26], conducted on ICU patients with various types of infection, demonstrated that using a PCT-guided algorithm (with thresholds of an absolute PCT value < 0.5 ng/mL or a ≥80% decline from peak levels to discontinue antibiotics) reduced antibiotic exposure by approximately 23% without increasing mortality or treatment failure.

- A large Dutch ICU study by de Jong et al. [30], focusing on patients with sepsis (including VAP), found that the PCT-guided group (using the same discontinuation thresholds of an absolute PCT value < 0.5 ng/mL or a ≥80% decline from peak levels) had shorter antibiotic courses and slightly lower mortality compared with standard care.

- A 2017 meta-analysis by Schuetz et al. [31] confirmed that PCT-guided antibiotic stewardship in respiratory infections leads to reduced antibiotic exposure and lower risk of antibiotic-related side effects, with no increase in morbidity or mortality. However, VAP accounted for only 6% of the cases in the included studies.

- Importantly for VAP, Stolz and colleagues conducted an RCT [32] on 101 VAP patients. This RCT specifically demonstrated that a PCT-guided strategy (absolute PCT value < 0.5 ng/mL or a ≥80% decline from peak levels) can safely shorten therapy duration in VAP. In this study, the PCT group had more antibiotic-free days alive by day 28 (median 13 days vs. 9.5 days in controls). This represented a 27% reduction in total antibiotic duration in the PCT group. Remarkably, there were no differences in clinical outcomes: mechanical ventilation days, ICU length of stay, and 28-day mortality were similar between PCT-guided and standard groups. Thus, PCT guidance achieved a reduction in treatment length without harming patients.

- The REGARD-VAP trial [10] discussed earlier, incorporated PCT use into its protocol—in the short-course arm, one of the criteria for antibiotic cessation was an 80% decline in PCT (alongside clinical criteria). Importantly, the REGARD-VAP trial did not incorporate rapid molecular diagnostic platforms nor perform analyses correlating specific resistance genes with clinical trajectories, relapse timing, or the need for antibiotic retreatment. Subgroup analyses were based on conventional culture-derived phenotypic resistance categories (e.g., NF-GNB and carbapenem-resistant organisms), and outcomes were assessed at the clinical rather than molecular level. Therefore, conclusions from REGARD-VAP should not be extrapolated to genotype-driven treatment duration strategies. Therefore, REGARD’s success in the short arm might have been partly enabled by PCT guidance.

- C-reactive protein (CRP): CRP is a widely available acute-phase reactant [36]. The UK ADAPT-Sepsis trial tested CRP-guided antibiotic duration versus PCT-guided and standard care in sepsis [37]. It found that PCT guidance reduced antibiotic days (by ~1 day) compared to the standard, whereas CRP guidance did not significantly reduce duration. Thus, CRP appears less useful than PCT for this purpose, possibly reflecting its lower specificity and slower decline.

- Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score (CPIS): This is a clinical composite score (fever, leukocytes, oxygenation, secretions, and culture results) sometimes used to assess pneumonia probability. Singh et al. [38] effectively used CPIS as a decision tool to shorten therapy in low-probability cases—if CPIS remained low after 3 days, antibiotics were stopped. While CPIS is not a biomarker per se, it is a clinical algorithm that can aid diagnostic stewardship. Current guidelines recommend against the use of CPIS for VAP diagnosis [1]. However, the German guidelines underscore the principle of re-evaluating at 48–72 h and discontinuing antibiotics if clinical evidence of pneumonia is lacking [15].

- Several other markers have been studied to improve antibiotic decision-making, but none have been validated as a tool to help tailor antibiotic duration in VAP [39,40]. One ICU study found that serial IL-6 monitoring might allow for shorter pneumonia treatment, but the results were not statistically significant [41]. Soluble triggering receptor on myeloid cells and pro-adrenomedullin are among experimental biomarkers, but none are in routine use for guiding duration yet [40].

- Rapid diagnostics and scoring tools: While not a serum biomarker, molecular diagnostics such as the FilmArray Pneumonia Panel offer rapid identification of common respiratory pathogens and resistance genes directly from lower respiratory tract samples [42,43,44]. By providing results within hours, these tools can facilitate earlier targeted de-escalation or help confirm pathogen identity, thereby supporting more individualized decisions about treatment duration rather than its initiation. However, important limitations must be acknowledged. A negative FilmArray result does not rule out infection since the panel covers a limited range of organisms and may miss less common or emerging pathogens [43,45]. Moreover, recent data suggests that repeated testing during therapy does not correlate with clinical outcomes or reduced duration, highlighting that interpretation must always occur within the full clinical context [45]. Beyond microbiological tools, imaging modalities such as lung ultrasound (LUS) are being evaluated to monitor pneumonia resolution. The proposed “CPIS-PLUS” concept—combining the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score with PCT trends and LUS findings—was designed to enhance treatment assessment response and potentially guide safe discontinuation rather than dictate antibiotic initiation [46,47]. Together, these emerging diagnostic-stewardship tools hold promise for refining decisions on how long to continue antibiotics in VAP, ensuring therapy is neither unnecessarily prolonged nor prematurely curtailed.

5. Pathogen-Specific and Patient-Specific Considerations

5.1. Non-Fermenting Gram-Negative Bacilli (Pseudomonas spp., Acinetobacter spp., and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia)

5.2. Carbapenem-Resistant and Difficult-to-Treat Organisms

5.3. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus VAP

5.4. Immunocompromised Patients

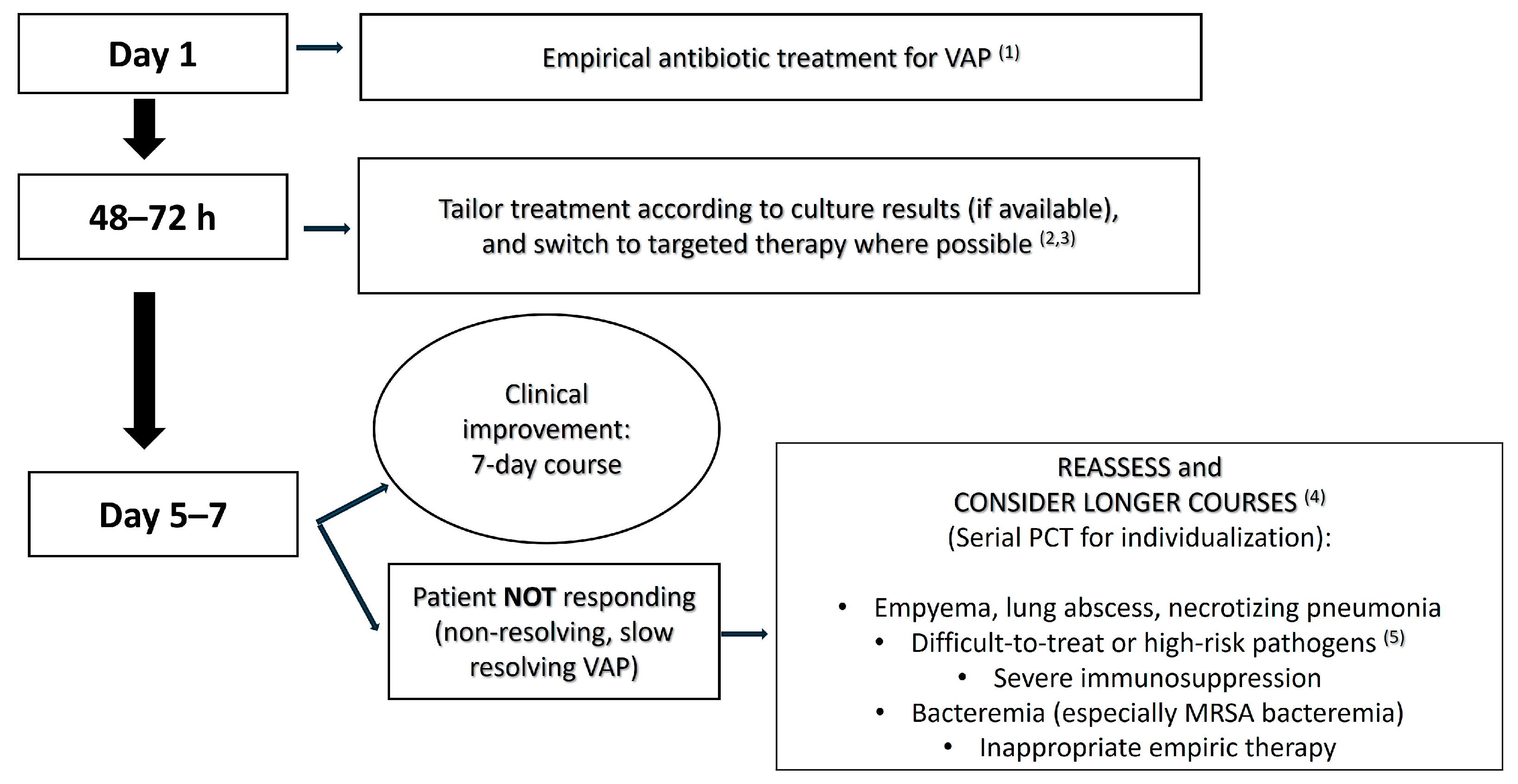

6. When to Consider Extending Therapy Beyond 7 Days

- Lack of clinical improvement by day 5–7: If a patient is not responding to therapy as the 1-week mark approaches (e.g., if they remain febrile, are still on high ventilator support, or are showing no improvement in oxygenation), continuation of the antibiotics with reassessment of the regimen is prudent [84]. Failure to improve raises concerns about inadequate source control, inappropriate antibiotic choice (e.g., due to a resistant pathogen or inadequate coverage), or complications. In such cases, stopping treatment at 7 days would be risky since the infection may not be cleared. Thus, persistent clinical signs of infection at the end of a short course warrant extension until improvement is seen and there is a rigorous evaluation of why the response is slow [84].

- Persistently high PCT and/or inflammatory markers: If biomarkers like PCT remain elevated or show minimal decline by day ~7, it may indicate ongoing infection [85]. Many PCT-guided protocols suggest not stopping antibiotics if PCT is still >0.5 ng/mL or does not decline by ~80% of its peak value [26,30,86]. For instance, a PCT that is minimally reduced by day 7 (e.g., from 5 to 4) may indicate insufficient infection control, suggesting the need for continued therapy. While PCT levels should only be interpreted in a clinical context (e.g., renal failure can keep PCT elevated), a stagnant or rising PCT by day 5–7 could justify prolonged therapy or at least prompt further investigation before stopping. Conversely, a low PCT despite clinical deterioration may indicate a nonbacterial cause (e.g., an organizing pneumonia). Thus, trends in PCT or other inflammatory markers can support decisions regarding treatment extension. Persistently elevated inflammatory markers in the absence of clinical improvement suggest ongoing infection and support the continuation of antibiotic therapy with reassessment.

- MDR/XDR pathogen with slow response: In cases where the causative pathogen is a difficult MDR (like CRAB, CRE, or DTR Pseudomonas) and the patient’s clinical improvement is slow, a longer course of treatment (e.g., 10–14-day course) may be warranted [17,21,69]. For example, suppose a patient with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter VAP is on appropriate therapy but by day 7 remains febrile and has purulent secretions—many would continue treatment given the pathogen’s recalcitrance. In REGARD-VAP, patients with MDR organisms did well with short courses if they improved. However, in practice, if improvement is lacking, clinicians extend therapy for these pathogens while monitoring closely [10]. Essentially, MDR VAP accompanied by a slow clinical resolution will likely require extension beyond 7 days in a case-by-case decision.

- Unresolved or complicated infection foci: Certain pulmonary complications inherently require longer treatment. Examples include lung abscesses, necrotizing pneumonia, empyema, or cavitating lesions [15,87]. These conditions often take more time to sterilize and sometimes necessitate adjunct procedures (drainage; surgery). Guidelines recommend extended therapy if an empyema cannot be fully drained, and the German guidelines for 2024 specifically advise prolonging therapy in such cases [15]. Similarly, necrotizing pneumonia or extensive lung destruction might clear more slowly. If imaging reveals a cavity or abscess, treatment is often extended beyond 7 days, with some cases requiring 3–4 weeks for abscesses, although data is scant in VAP-related abscesses [88]. In summary, unresolved foci mean an unresolved infection, necessitating continued therapy as well as attempts at source control.

- Bacteremia or extrapulmonary spread: Any VAP episode accompanied by bacteremia, especially with organisms like S. aureus, generally warrants extending treatment [79]. In cases of bloodstream infection, antibiotics are typically continued for 10–14 days, depending on the organism, to ensure complete clearance from the blood and prevent metastatic seeding [79,83]. For instance, VAP with MRSA bacteremia necessitates at least 14 days per MRSA guidelines [79]. However, this dogma is also under debate, as a recent RCT elucidates that even in an uncomplicated Gram-negative bloodstream infection, 7 days of antibiotic treatment seems sufficient [80]. Likewise, if the pneumonia has seeded to other sites (septic emboli to other organs, septic arthritis, etc.), the total duration must cover treatment of those secondary sites. Essentially, once infection is systemic or outside the lungs, it is no longer just “VAP”, but rather, it is a disseminated infection requiring a longer course. Always follow up blood cultures and consult relevant guidelines for bacteremic pneumonias.

- Immunosuppression: Although evidence is lacking, as noted, many clinicians err on longer treatment in immunocompromised patients [89]. For example, in a neutropenic leukemia patient with VAP, one might treat for 10–14 days since their neutrophils (key for bacterial clearance) are low [90]. The rationale is that in an immune-weakened host, the clearance of bacteria may be slower even if on appropriate antibiotics, so additional days of therapy might help prevent relapse once antibiotics are stopped. This is more of an expert-opinion stance rather than evidence-based, but it is commonly practiced. Importantly, one should also accelerate supportive measures to restore immune function (e.g., granulocyte colony-stimulating factor if neutropenic; reducing immunosuppressants if feasible) because antibiotics alone might not suffice if the immune system is dampened.

7. The Evolving Stewardship Paradigm and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A. baumannii | Acinetobacter baumannii |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| ATS | American Thoracic Society |

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar lavage |

| CPIS | Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score |

| CPIS-PLUS | Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score plus procalcitonin and lung ultrasound |

| CRAB | Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii |

| CRE | Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CRPA | Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DGIIN | German Society of Internal Intensive Care Medicine |

| DTR | Difficult-to-treat resistance |

| DZIF | German Center for Infection Research |

| ERS | European Respiratory Society |

| ESCMID | European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases |

| ESICM | European Society of Intensive Care Medicine |

| HAP | Hospital-acquired pneumonia |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IDSA | Infectious Diseases Society of America |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| LUS | Lung ultrasound |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| NF-GNB | Non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli |

| P. aeruginosa | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| PCT | Procalcitonin |

| PK/PD | Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

| S. maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia |

| SFAR | French Society of Anesthesia and Resuscitation |

| TMP-SMX | Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole |

| VAP | Ventilator-associated pneumonia |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

References

- Kalil, A.C.; Metersky, M.L.; Klompas, M.; Muscedere, J.; Sweeney, D.A.; Palmer, L.B.; Napolitano, L.M.; O’Grady, N.P.; Bartlett, J.G.; Carratala, J.; et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, e61–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Niederman, M.S.; Chastre, J.; Ewig, S.; Fernandez-Vandellos, P.; Hanberger, H.; Kollef, M.; Li Bassi, G.; Luna, C.M.; Martin-Loeches, I.; et al. International ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)/ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) of the European Respiratory Society (ERS), European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and Asociacion Latinoamericana del Torax (ALAT). Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulenti, D.; Lisboa, T.; Brun-Buisson, C.; Krueger, W.; Macor, A.; Sole-Violan, J.; Diaz, E.; Topeli, A.; DeWaele, J.; Carneiro, A.; et al. Spectrum of practice in the diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia in patients requiring mechanical ventilation in European intensive care units. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 2360–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulenti, D.; Tsigou, E.; Rello, J. Nosocomial pneumonia in 27 ICUs in Europe: Perspectives from the EU-VAP/CAP study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planquette, B.; Timsit, J.F.; Misset, B.Y.; Schwebel, C.; Azoulay, E.; Adrie, C.; Vesin, A.; Jamali, S.; Zahar, J.R.; Allaouchiche, B.; et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia. predictive factors of treatment failure. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Estrada, S.; Borgatta, B.; Rello, J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia management. Infect. Drug. Resist. 2016, 9, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nora, D.; Povoa, P. Antibiotic consumption and ventilator-associated pneumonia rates, some parallelism but some discrepancies. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnimr, A. Antimicrobial Resistance in Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: Predictive Microbiology and Evidence-Based Therapy. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2023, 12, 1527–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chastre, J.; Wolff, M.; Fagon, J.Y.; Chevret, S.; Thomas, F.; Wermert, D.; Clementi, E.; Gonzalez, J.; Jusserand, D.; Asfar, P.; et al. Comparison of 8 vs. 15 days of antibiotic therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: A randomized trial. JAMA 2003, 290, 2588–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Booraphun, S.; Li, A.Y.; Domthong, P.; Kayastha, G.; Lau, Y.H.; Chetchotisakd, P.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; Tambyah, P.A.; Cooper, B.S.; et al. Individualised, short-course antibiotic treatment versus usual long-course treatment for ventilator-associated pneumonia (REGARD-VAP): A multicentre, individually randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, H.A.; Ellahi, A.; Hussain, H.U.; Kashif, H.; Adil, M.; Kumar, D.; Shahid, A.; Ehsan, M.; Singh, H.; Duric, N.; et al. Short-course versus prolonged-course antibiotic regimens for ventilator-associated pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Crit. Care 2023, 78, 154346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajander, S.; Kox, M.; Scicluna, B.P.; Weigand, M.A.; Mora, R.A.; Flohe, S.B.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Lachmann, G.; Girardis, M.; Garcia-Salido, A.; et al. Profiling the dysregulated immune response in sepsis: Overcoming challenges to achieve the goal of precision medicine. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, M.; Bouadma, L.; Bouhemad, B.; Brissaud, O.; Dauger, S.; Gibot, S.; Hraiech, S.; Jung, B.; Kipnis, E.; Launey, Y.; et al. Brief summary of French guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia in ICU. Ann. Intensive Care 2018, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, T.T.; Cao, B.; Wang, H.; Zhuo, C.; Ye, F.; Su, X.; Fan, H.; Xu, J.F.; et al. Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults (2018 Edition). J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, 2581–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, J.; Ewig, S.; Grabein, B.; Nachtigall, I.; Abele-Horn, M.; Deja, M.; Gassner, M.; Gatermann, S.; Geffers, C.; Gerlach, H.; et al. Key summary of German national guideline for adult patients with nosocomial pneumonia- Update 2024 Funding number at the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA): 01VS.F22007. Infection 2024, 52, 2531–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, L.F.; Serrano-Mayorga, C.C.; Zhang, Z.; Tsuji, I.; De Pascale, G.; Prieto, V.E.; Mer, M.; Sheehan, E.; Nasa, P.; Zangana, G.; et al. D-PRISM: A global survey-based study to assess diagnostic and treatment approaches in pneumonia managed in intensive care. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougle, A.; Tuffet, S.; Federici, L.; Leone, M.; Monsel, A.; Dessalle, T.; Amour, J.; Dahyot-Fizelier, C.; Barbier, F.; Luyt, C.E.; et al. Comparison of 8 versus 15 days of antibiotic therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: A randomized, controlled, open-label trial. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghmouri, M.A.; Dudoignon, E.; Chaouch, M.A.; Baekgaard, J.; Bougle, A.; Leone, M.; Deniau, B.; Depret, F. Comparison of a short versus long-course antibiotic therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 58, 101880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valladares, C.; Gregory, B.; Seeburun, S.; Al Mahrizi, A.D.; Shambhavi, S.; Kaplan, A.; Khan, W. Prophylactic Inhaled Antibiotics for Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Incidence and Mortality Outcomes. Lung 2025, 203, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, R.; Grant, C.; Cooke, R.P.; Dempsey, G. Short-course versus prolonged-course antibiotic therapy for hospital-acquired pneumonia in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD007577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, C.N.; Chin-Beckford, N.; Vega, A.; DeRonde, K.; Simon, J.; Abbo, L.M.; Rosa, R.; Vu, C.A. Duration of antibiotic therapy for multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia: Is shorter truly better? BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Musawa, M.; Caniff, K.E.; Judd, C.; Veve, M.; Rybak, M.J. P-289. Short-Duration vs. Long-Duration of Therapy for Hospital-Acquired or Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia due to Multi-Drug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Open Forum. Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofae631.492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, M.; Gmehlin, C.G.; Vukoja, M.; Dong, Y.; Gajic, O.; Tekin, A.; Checklist for Early, R.; Treatment of Acute, I.; Injury Study, I. Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Low- and Middle-Income vs. High-Income Countries: The Role of Ventilator Bundle, Ventilation Practices, and Health Care Staffing. Chest 2025, 167, 1628–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillet, A.; Luyt, C.E.; Timsit, J.F.; Asehnoune, K.; Barbier, F.; Bassetti, M.; Bouadma, L.; Bougle, A.; Chastre, J.; Morris, A.C.; et al. A consensus of European experts on the definition of ventilator-associated pneumonia recurrences obtained by the Delphi method: The RECUVAP study. Intensive Care Med. 2025, 51, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenot, J.P.; Luyt, C.E.; Roche, N.; Chalumeau, M.; Charles, P.E.; Claessens, Y.E.; Lasocki, S.; Bedos, J.P.; Pean, Y.; Philippart, F.; et al. Role of biomarkers in the management of antibiotic therapy: An expert panel review II: Clinical use of biomarkers for initiation or discontinuation of antibiotic therapy. Ann. Intensive Care 2013, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouadma, L.; Luyt, C.E.; Tubach, F.; Cracco, C.; Alvarez, A.; Schwebel, C.; Schortgen, F.; Lasocki, S.; Veber, B.; Dehoux, M.; et al. Use of procalcitonin to reduce patients’ exposure to antibiotics in intensive care units (PRORATA trial): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010, 375, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.B.; Peng, J.M.; Weng, L.; Wang, C.Y.; Jiang, W.; Du, B. Procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy in intensive care unit patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intensive Care 2017, 7, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuetz, P.; Briel, M.; Christ-Crain, M.; Stolz, D.; Bouadma, L.; Wolff, M.; Luyt, C.E.; Chastre, J.; Tubach, F.; Kristoffersen, K.B.; et al. Procalcitonin to guide initiation and duration of antibiotic treatment in acute respiratory infections: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Clin. Infect Dis. 2012, 55, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, M.; Kiss, N.; Baka, M.; Trásy, D.; Zubek, L.; Fehérvári, P.; Harnos, A.; Turan, C.; Hegyi, P.; Molnár, Z. Procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy may shorten length of treatment and may improve survival—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, E.; van Oers, J.A.; Beishuizen, A.; Vos, P.; Vermeijden, W.J.; Haas, L.E.; Loef, B.G.; Dormans, T.; van Melsen, G.C.; Kluiters, Y.C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: A randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, P.; Wirz, Y.; Sager, R.; Christ-Crain, M.; Stolz, D.; Tamm, M.; Bouadma, L.; Luyt, C.E.; Wolff, M.; Chastre, J.; et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment on mortality in acute respiratory infections: A patient level meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolz, D.; Smyrnios, N.; Eggimann, P.; Pargger, H.; Thakkar, N.; Siegemund, M.; Marsch, S.; Azzola, A.; Rakic, J.; Mueller, B.; et al. Procalcitonin for reduced antibiotic exposure in ventilator-associated pneumonia: A randomised study. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 1364–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulon, N.; Haeger, S.M.; Okamura, K.; He, Z.; Park, B.D.; Budnick, I.M.; Madison, D.; Kennis, M.; Blaine, R.; Miyazaki, M.; et al. Procalcitonin levels in septic and nonseptic subjects with AKI and ESKD prior to and during continuous kidney replacement therapy (CKRT). Crit. Care 2025, 29, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtaszek, M.; Staskiewicz, G.; Torres, K.; Jakubowski, K.; Racz, O.; Cipora, E. Changes of procalcitonin level in multiple trauma patients. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 2014, 46, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parli, S.E.; Trivedi, G.; Woodworth, A.; Chang, P.K. Procalcitonin: Usefulness in Acute Care Surgery and Trauma. Surg. Infect. 2018, 19, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Dach, E.; Albrich, W.C.; Brunel, A.S.; Prendki, V.; Cuvelier, C.; Flury, D.; Gayet-Ageron, A.; Huttner, B.; Kohler, P.; Lemmenmeier, E.; et al. Effect of C-Reactive Protein-Guided Antibiotic Treatment Duration, 7-Day Treatment, or 14-Day Treatment on 30-Day Clinical Failure Rate in Patients With Uncomplicated Gram-Negative Bacteremia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 323, 2160–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dark, P.; Hossain, A.; McAuley, D.F.; Brealey, D.; Carlson, G.; Clayton, J.C.; Felton, T.W.; Ghuman, B.K.; Gordon, A.C.; Hellyer, T.P.; et al. Biomarker-Guided Antibiotic Duration for Hospitalized Patients With Suspected Sepsis: The ADAPT-Sepsis Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Rogers, P.; Atwood, C.W.; Wagener, M.M.; Yu, V.L. Short-course empiric antibiotic therapy for patients with pulmonary infiltrates in the intensive care unit. A proposed solution for indiscriminate antibiotic prescription. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 162, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bexten, T.; Wiebe, S.; Brink, M.; Hinzmann, D.; Haarmeyer, G.S. Early Detection of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in a Neurosurgical Patient: Do Biomarkers Help Us? Cureus 2025, 17, e78567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulin, L.B.S.; de Lange, D.W.; Saleh, M.A.A.; van der Graaf, P.H.; Voller, S.; van Hasselt, J.G.C. Biomarker-Guided Individualization of Antibiotic Therapy. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 110, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidhase, L.; Wellhofer, D.; Schulze, G.; Kaiser, T.; Drogies, T.; Wurst, U.; Petros, S. Is Interleukin-6 a better predictor of successful antibiotic therapy than procalcitonin and C-reactive protein? A single center study in critically ill adults. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Ruan, S.Y.; Pan, S.C.; Lee, T.F.; Chien, J.Y.; Hsueh, P.R. Performance of a multiplex PCR pneumonia panel for the identification of respiratory pathogens and the main determinants of resistance from the lower respiratory tract specimens of adult patients in intensive care units. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019, 52, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessajan, J.; Timsit, J.F. Impact of Multiplex PCR in the Therapeutic Management of Severe Bacterial Pneumonia. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Perez-Torres, D.; Fragkou, P.C.; Zahar, J.R.; Koulenti, D. Nosocomial Pneumonia in the Era of Multidrug-Resistance: Updates in Diagnosis and Management. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessajan, J.; Thy, M.; Doman, M.; Stern, J.; Gallet, A.; Fouque, G.; Chosidow, S.; Ruckly, S.; Gueye, S.; Lamara, F.; et al. Assessing FilmArray Pneumonia+ panel dynamics during antibiotic treatment to predict clinical success in ICU patients with ventilated hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: A multicenter prospective study. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriao, D.; Mojoli, F.; Gregorio Hernandez, R.; De Luca, D.; Bouhemad, B.; Mongodi, S. Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: An Update on the Role of Lung Ultrasound in Adult, Pediatric, and Neonatal ICU Practice. Ther. Adv. Pulm. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 20, 29768675251349632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howroyd, F.; Gill, R.; Thompson, J.; Smith, F.G.; Nasa, P.; Gopal, S.; Duggal, N.A.; Ahmed, Z.; Veenith, T. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: Mechanisms, an appraisal of current therapies and the role for inhaled antibiotics in prevention and treatment. Respir. Med. 2025, 247, 108275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickens, C.I.; Wunderink, R.G. Principles and Practice of Antibiotic Stewardship in the ICU. Chest 2019, 156, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roper, S.; Wingler, M.J.B.; Cretella, D.A. Antibiotic De-Escalation in Critically Ill Patients with Negative Clinical Cultures. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ-Crain, M.; Stolz, D.; Bingisser, R.; Muller, C.; Miedinger, D.; Huber, P.R.; Zimmerli, W.; Harbarth, S.; Tamm, M.; Muller, B. Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: A randomized trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 174, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, P.; Christ-Crain, M.; Thomann, R.; Falconnier, C.; Wolbers, M.; Widmer, I.; Neidert, S.; Fricker, T.; Blum, C.; Schild, U.; et al. Effect of procalcitonin-based guidelines vs. standard guidelines on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: The ProHOSP randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009, 302, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, R.M.E.; Oerlemans, A.J.M.; van der Hoeven, J.G.; Oostdijk, E.A.N.; Derde, L.P.G.; Ten Oever, J.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Hulscher, M.; Schouten, J.A. Decision-making regarding antibiotic therapy duration: An observational study of multidisciplinary meetings in the intensive care unit. J. Crit. Care 2023, 78, 154363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albin, O.; Nadimidla, S.; Saravolatz, L.; Barker, A.; Wayne, M.; Rockney, D.; Jean, R.; Nguyen, A.; Diwan, M.; Pierce, V.; et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia biomarker evaluation (VIBE) study: Protocol for a prospective, observational, case-cohort study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e110019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulenti, D.; Almyroudi, M.P.; Katsounas, A. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: How long is long enough? Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2025, 31, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, S.F.; Allaw, F.; Kanj, S.S. Duration of antibiotic therapy in Gram-negative infections with a particular focus on multidrug-resistant pathogens. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 35, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshmukh-Reeves, E.; Shaw, M.; Bilsby, C.; Gourlay, C.W. Biofilm Formation on Endotracheal and Tracheostomy Tubing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Culture Data and Sampling Method. Microbiologyopen 2025, 14, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice, N.M.; Bedi, B.; Sadikot, R.T. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms: Host Response and Clinical Implications in Lung Infections. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 58, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Eggimann, P.; Luyt, C.E.; Wolff, M.; Tamm, M.; Francois, B.; Mercier, E.; Garbino, J.; Laterre, P.F.; Koch, H.; et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotypes in nosocomial pneumonia: Prevalence and clinical outcomes. Crit. Care 2014, 18, R17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles, J.; Mariscal, D.; Cortes, P.; Coll, P.; Villagra, A.; Diaz, E.; Artigas, A.; Rello, J. Patterns of colonization by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in intubated patients: A 3-year prospective study of 1607 isolates using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis with implications for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2004, 30, 1768–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoiby, N.; Ciofu, O.; Johansen, H.K.; Song, Z.J.; Moser, C.; Jensen, P.O.; Molin, S.; Givskov, M.; Tolker-Nielsen, T.; Bjarnsholt, T. The clinical impact of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 3, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasamiravaka, T.; Vandeputte, O.M.; Pottier, L.; Huet, J.; Rabemanantsoa, C.; Kiendrebeogo, M.; Andriantsimahavandy, A.; Rasamindrakotroka, A.; Stevigny, C.; Duez, P.; et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm Formation and Persistence, along with the Production of Quorum Sensing-Dependent Virulence Factors, Are Disrupted by a Triterpenoid Coumarate Ester Isolated from Dalbergia trichocarpa, a Tropical Legume. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabot, G.; Zamorano, L.; Moya, B.; Juan, C.; Navas, A.; Blazquez, J.; Oliver, A. Evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Antimicrobial Resistance and Fitness under Low and High Mutation Rates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Price, L.S.; Weinstein, R.A. Acinetobacter infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsit, J.F.; Bassetti, M.; Cremer, O.; Daikos, G.; de Waele, J.; Kallil, A.; Kipnis, E.; Kollef, M.; Laupland, K.; Paiva, J.A.; et al. Rationalizing antimicrobial therapy in the ICU: A narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viehman, J.A.; Nguyen, M.H.; Doi, Y. Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Drugs 2014, 74, 1315–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulenti, D.; Vandana, K.E.; Rello, J. Current viewpoint on the epidemiology of nonfermenting Gram-negative bacterial strains. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 36, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerci, P.; Bellut, H.; Mokhtari, M.; Gaudefroy, J.; Mongardon, N.; Charpentier, C.; Louis, G.; Tashk, P.; Dubost, C.; Ledochowski, S.; et al. Outcomes of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia hospital-acquired pneumonia in intensive care unit: A nationwide retrospective study. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puech, B.; Canivet, C.; Teysseyre, L.; Miltgen, G.; Aujoulat, T.; Caron, M.; Combe, C.; Jabot, J.; Martinet, O.; Allyn, J.; et al. Effect of antibiotic therapy on the prognosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Ann. Intensive Care 2021, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Heil, E.L.; Justo, J.A.; Mathers, A.J.; Satlin, M.J.; Bonomo, R.A. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2024 Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, ciae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzynski, S.H.; Warner, S.; Sun, J.; Matsouaka, R.; Dekker, J.P.; Babiker, A.; Li, W.; Lai, Y.L.; Danner, R.L.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; et al. Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole Versus Levofloxacin for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infections: A Retrospective Comparative Effectiveness Study of Electronic Health Records from 154 US Hospitals. Open Forum. Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofab644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz Coyne, A.J.; Lucas, K.; Gray, R.; May, E. Propensity-Matched Comparison of Timely vs. Delayed Antibiotic Therapy in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Pneumonia. Open Forum. Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettori, S.; Portunato, F.; Vena, A.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Bassetti, M. Severe infections caused by difficult-to-treat Gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2023, 29, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, M.; Peghin, M.; Vena, A.; Giacobbe, D.R. Treatment of Infections Due to MDR Gram-Negative Bacteria. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Carrara, E.; Retamar, P.; Tangden, T.; Bitterman, R.; Bonomo, R.A.; de Waele, J.; Daikos, G.L.; Akova, M.; Harbarth, S.; et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidelines for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli (endorsed by European society of intensive care medicine). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollef, M.H.; Novacek, M.; Kivistik, U.; Rea-Neto, A.; Shime, N.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Timsit, J.F.; Wunderink, R.G.; Bruno, C.J.; Huntington, J.A.; et al. Ceftolozane-tazobactam versus meropenem for treatment of nosocomial pneumonia (ASPECT-NP): A randomised, controlled, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, A.; Zhong, N.; Pachl, J.; Timsit, J.F.; Kollef, M.; Chen, Z.; Song, J.; Taylor, D.; Laud, P.J.; Stone, G.G.; et al. Ceftazidime-avibactam versus meropenem in nosocomial pneumonia, including ventilator-associated pneumonia (REPROVE): A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderink, R.G.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ariyasu, M.; Clevenbergh, P.; Echols, R.; Kaye, K.S.; Kollef, M.; Menon, A.; Pogue, J.M.; Shorr, A.F.; et al. Cefiderocol versus high-dose, extended-infusion meropenem for the treatment of Gram-negative nosocomial pneumonia (APEKS-NP): A randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, A.P.; Wunderink, R.G. Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: Strategies to Prevent and Treat. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 27, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.P.; Moon, S.M.; Bang, K.M.; Park, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, M.N.; Park, K.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.O.; Choi, S.H.; et al. Treatment duration for uncomplicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia to prevent relapse: Analysis of a prospective observational cohort study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Balance Investigators, for the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group; The Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada Clinical Research Network; The Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, and the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Network. Antibiotic Treatment for 7 versus 14 Days in Patients with Bloodstream Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1065–1078. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bayer, A.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Daum, R.S.; Fridkin, S.K.; Gorwitz, R.J.; Kaplan, S.L.; Karchmer, A.W.; Levine, D.P.; Murray, B.E.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: Executive summary. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollef, M.H.; Shorr, A.; Tabak, Y.P.; Gupta, V.; Liu, L.Z.; Johannes, R.S. Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associated pneumonia: Results from a large US database of culture-positive pneumonia. Chest 2005, 128, 3854–3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbaht, K.; Diaz, E.; Munoz, E.; Lisboa, T.; Gomez, F.; Depuydt, P.O.; Blot, S.I.; Rello, J. Bacteremia in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia is associated with increased mortality: A study comparing bacteremic vs. nonbacteremic ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 2064–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povoa, P.; Coelho, L.; Carratala, J.; Cawcutt, K.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Ferrer, R.; Gomez, C.A.; Klompas, M.; Lisboa, T.; Martin-Loeches, I.; et al. How to approach a patient hospitalized for pneumonia who is not responding to treatment? Intensive Care Med. 2025, 51, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeboer, S.H.; Groeneveld, A.B. Changes in circulating procalcitonin versus C-reactive protein in predicting evolution of infectious disease in febrile, critically ill patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, D.J.; Sun, J.; Rhee, C.; Welsh, J.; Powers, J.H., 3rd; Danner, R.L.; Kadri, S.S. Procalcitonin-Guided Antibiotic Discontinuation and Mortality in Critically Ill Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest 2019, 155, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, G.; Poulakou, G.; Pneumatikos, I.A.; Armaganidis, A.; Kollef, M.H.; Matthaiou, D.K. Short- vs. long-duration antibiotic regimens for ventilator-associated pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2013, 144, 1759–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hraiech, S.; Ladjal, K.; Guervilly, C.; Hyvernat, H.; Papazian, L.; Forel, J.M.; Lopez, A.; Peres, N.; Dellamonica, J.; Leone, M.; et al. Lung abscess following ventilator-associated pneumonia during COVID-19: A retrospective multicenter cohort study. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imlay, H.; Laundy, N.C.; Forrest, G.N.; Slavin, M.A. Shorter antibiotic courses in the immunocompromised: The impossible dream? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freifeld, A.G.; Bow, E.J.; Sepkowitz, K.A.; Boeckh, M.J.; Ito, J.I.; Mullen, C.A.; Raad, I.I.; Rolston, K.V.; Young, J.A.; Wingard, J.R.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, e56–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensgens, M.P.; Goorhuis, A.; Dekkers, O.M.; Kuijper, E.J. Time interval of increased risk for Clostridium difficile infection after exposure to antibiotics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klompas, M.; Branson, R.; Cawcutt, K.; Crist, M.; Eichenwald, E.C.; Greene, L.R.; Lee, G.; Maragakis, L.L.; Powell, K.; Priebe, G.P.; et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia, ventilator-associated events, and nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia in acute-care hospitals: 2022 Update. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 687–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klompas, M. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: Is zero possible? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 1123–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishima, Y.; Nawa, N.; Asada, M.; Nagashima, M.; Aiso, Y.; Nukui, Y.; Fujiwara, T.; Shigemitsu, H. Impact of Antibiotic Time-Outs in Multidisciplinary ICU Rounds for Antimicrobial Stewardship Program on Patient Survival: A Controlled Before-and-After Study. Crit. Care Explor. 2023, 5, e0837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, C.; Koulenti, D.; Novy, E.; Roberts, J.; Dahyot-Fizelier, C. Optimization of antimicrobial therapy in critically ill patients, what clinicians and searchers must know. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain. Med. 2025, 44, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulenti, D.; Roger, C.; Lipman, J. Antibiotic dosing optimization in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2025, 51, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.A.; Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Lipman, J.; Mouton, J.W.; Vinks, A.A.; Felton, T.W.; Hope, W.W.; Farkas, A.; Neely, M.N.; Schentag, J.J.; et al. Individualised antibiotic dosing for patients who are critically ill: Challenges and potential solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Castro, D.; Dresser, L.; Granton, J.; Fan, E. Pharmacokinetic Alterations Associated with Critical Illness. Clin. Pharmacokinet 2023, 62, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, J.; Lewis, R.E. The long walk to a short half-life: The discovery of augmented renal clearance and its impact on antibiotic dosing. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 3367–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilhaumou, R.; Benaboud, S.; Bennis, Y.; Dahyot-Fizelier, C.; Dailly, E.; Gandia, P.; Goutelle, S.; Lefeuvre, S.; Mongardon, N.; Roger, C.; et al. Optimization of the treatment with beta-lactam antibiotics in critically ill patients-guidelines from the French Society of Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Societe Francaise de Pharmacologie et Therapeutique-SFPT) and the French Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine (Societe Francaise d’Anesthesie et Reanimation-SFAR). Crit. Care 2019, 23, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulhunty, J.M.; Brett, S.J.; De Waele, J.J.; Rajbhandari, D.; Billot, L.; Cotta, M.O.; Davis, J.S.; Finfer, S.; Hammond, N.E.; Knowles, S.; et al. Continuous vs. Intermittent beta-Lactam Antibiotic Infusions in Critically Ill Patients With Sepsis: The BLING III Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 332, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejada, D.A.; Garcia, H.C.; Tomas-Alvarado, E.; Yangali-Vicente, J.; Rivera-Lozada, O.; Barboza, J.J. Continuous versus intermittent infusion of beta-lactams in patients with sepsis and septic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povoa, P.; Moniz, P.; Pereira, J.G.; Coelho, L. Optimizing Antimicrobial Drug Dosing in Critically Ill Patients. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelhassan, Y.P.; Nicolau, D. Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Optimization of Hospital-Acquired and Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: Challenges and Strategies. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 43, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandon, J.L.; Luyt, C.E.; Aubry, A.; Chastre, J.; Nicolau, D.P. Pharmacodynamics of carbapenems for the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia: Associations with clinical outcome and recurrence. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 2534–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicasio, A.M.; Eagye, K.J.; Nicolau, D.P.; Shore, E.; Palter, M.; Pepe, J.; Kuti, J.L. Pharmacodynamic-based clinical pathway for empiric antibiotic choice in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. J. Crit. Care 2010, 25, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phe, K.; Heil, E.L.; Tam, V.H. Optimizing Pharmacokinetics-Pharmacodynamics of Antimicrobial Management in Patients with Sepsis: A Review. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, S132–S141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, S.; Clark, T.W. Rapid syndromic molecular testing in pneumonia: The current landscape and future potential. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccobono, E.; Bussini, L.; Giannella, M.; Viale, P.; Rossolini, G.M. Rapid diagnostic tests in the management of pneumonia. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 22, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B.; Klamer, K.; Zimmerman, J.; Kale-Pradhan, P.B.; Bhargava, A. Multidrug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Clinical Settings: A Review of Resistance Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies. Pathogens 2024, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Cortes, P.; Campos-Fernandez, S.; Cuenca-Fito, E.; Del Rio-Carbajo, L.; Fernandez-Ugidos, P.; Lopez-Ciudad, V.J.; Nieto-Del Olmo, J.; Rodriguez-Vazquez, A.; Tizon-Varela, A.I. Difficult-to-Treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections in Critically Ill Patients: A Comprehensive Review and Treatment Proposal. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Guideline (Year) | Recommended Duration | Notable Caveats/Comments |

|---|---|---|

| IDSA/ATS (USA, 2016); [1] | 7 days (preferred) | Strong recommendation. Longer therapy only if evidence of ongoing infection despite 7 days. Emphasizes reducing antibiotic exposure. |

| ERS/ESICM/ESCMID (Europe, 2017); [2] | 7–8 days (conditional recommendation) | Include difficult pathogens in 7–8d course if clinically improving. Extend duration if poor clinical response, immunocompromised host, or complications (e.g., empyema). |

| French HAP Guideline—SFAR (2018); [13] | 7 days (strong recommendation) | Similar to IDSA; based on evidence that 7d is generally sufficient. Acknowledges Pseudomonas may relapse more often with short course, but no survival difference. |

| China Thoracic Society (2018); [14] | 7–10 days (typical range) | Usually, 7d adequate; up to 10d often used in practice. Extend past 10d if slow improvement, MDR pathogen, or immune deficit. Recommends adjunct PCT monitoring to inform duration. |

| German National Guideline—DZIF/DGIIN (2024); [15] | Approx. 7 days (standard for VAP) | Reiterate 7d if clinical response. For unresolved foci (e.g., undrained pleural infection) or ongoing signs of infection at day 7, consider longer (10–14d). Suggests biomarkers (PCT) can aid decisions in equivocal cases. |

| Clinical Scenario | Rationale for Extended Therapy | Typical Duration | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow or incomplete clinical response (persistent fever, elevated inflammatory markers) | Indicates delayed infection control or alternative foci | 10–14 days, reassess every 48 h | Expert consensus |

| Bacteremia or endocarditis due to the VAP pathogen | Requires systemic source control and ensures adequate sterilization | 10–14 days, depending on source | Evidence-based |

| Empyema, abscess, or necrotizing pneumonia | Reduced antibiotic penetration and higher bacterial load | ≥14 days, individualized | Evidence-based |

| Inappropriate initial empiric therapy | Delayed pathogen control increases recurrence risk | Count duration from first active therapy | Expert consensus |

| Infections with difficult-to-treat or high-risk pathogens (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, MRSA, NF-GNB) | Potential for persistence and biofilm formation | 10–14 days depending on course | Evidence-based |

| Severe immunosuppression (neutropenia, transplantation, high-dose steroids, advanced malignancy) | Impaired host defence; slower bacterial clearance | ≥10 days or until immune recovery | Expert consensus |

| Uncontrolled or ongoing infectious focus (e.g., unremoved device, open chest, uncontrolled drainage) | Ongoing inoculum prevents eradication | Continue until source control achieved | Expert consensus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rahmel, T.; Traut, I.; Bergmann, L.; Almyroudi, M.P.; Tamowicz, B.; Varma, P.; Koulenti, D.; Katsounas, A. Duration Matters: Tailoring Antibiotic Therapy for Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010034

Rahmel T, Traut I, Bergmann L, Almyroudi MP, Tamowicz B, Varma P, Koulenti D, Katsounas A. Duration Matters: Tailoring Antibiotic Therapy for Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahmel, Tim, Isabella Traut, Lars Bergmann, Maria Panagiota Almyroudi, Barbara Tamowicz, Priyam Varma, Despoina Koulenti, and Antonios Katsounas. 2026. "Duration Matters: Tailoring Antibiotic Therapy for Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010034

APA StyleRahmel, T., Traut, I., Bergmann, L., Almyroudi, M. P., Tamowicz, B., Varma, P., Koulenti, D., & Katsounas, A. (2026). Duration Matters: Tailoring Antibiotic Therapy for Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. Antibiotics, 15(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010034