Clinical Outcomes and Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Difficult-to-Treat Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

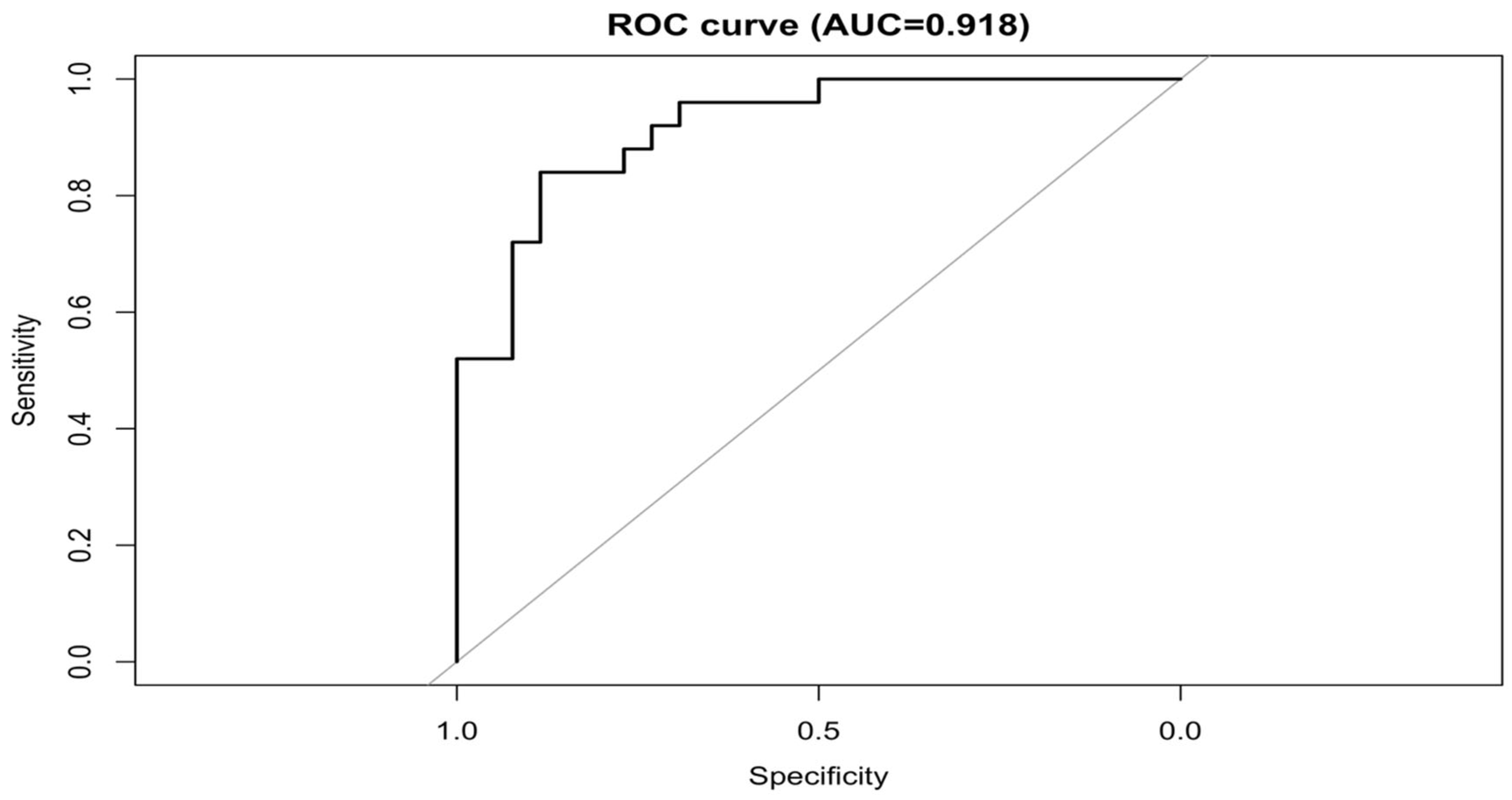

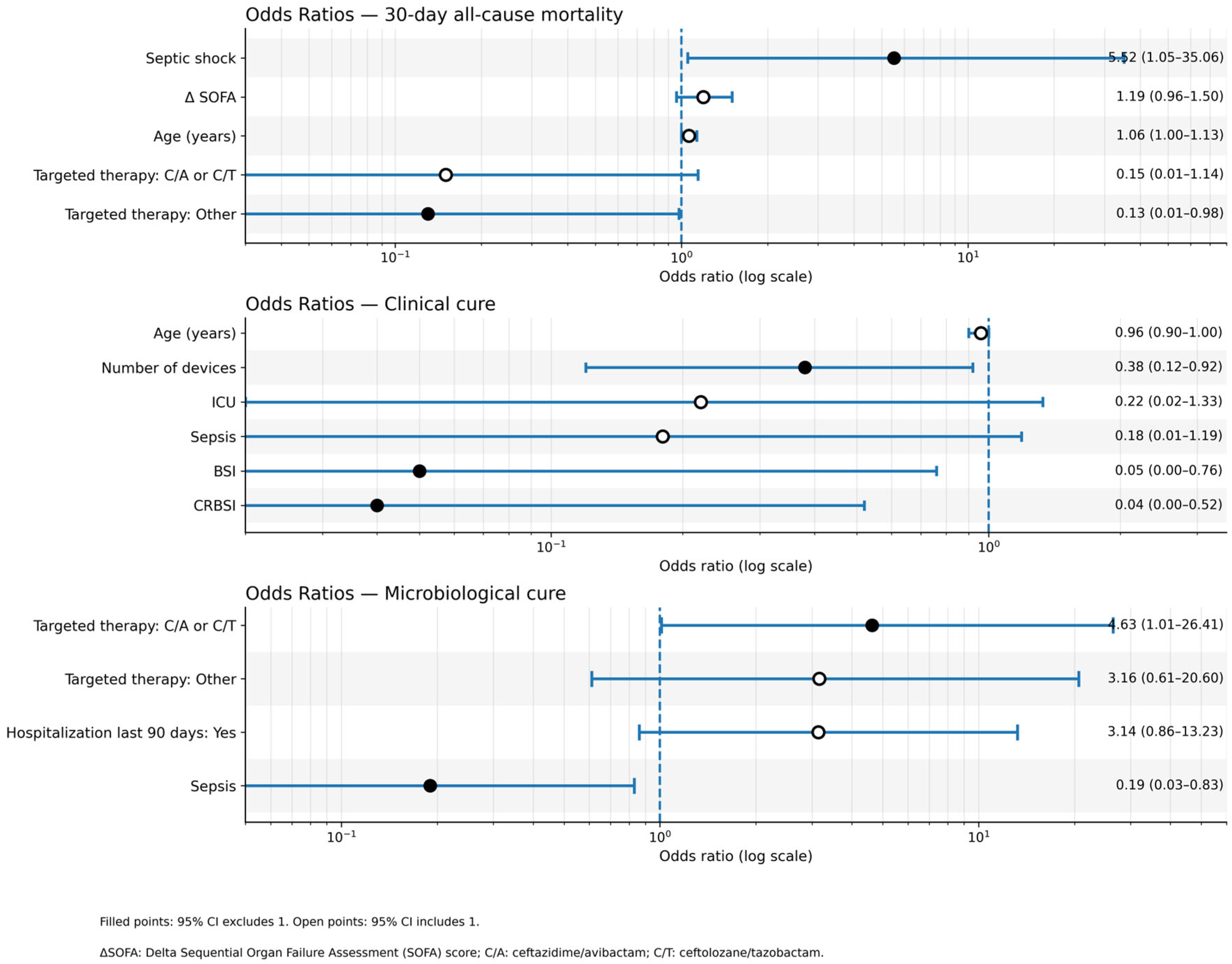

2.1. Primary Outcome: 30-Day All-Cause Mortality

- Septic Shock: (adjusted OR [aOR] 5.52; 95% CI 1.04–29.27; p = 0.045);

- Age: (aOR 1.06; 95% CI 1.00–1.12; p = 0.052);

- Targeted Therapy, namely Receiving “Other” targeted therapy (vs. no targeted therapy) was associated with lower mortality (aOR 0.13; 95% CI 0.02–1.02; p = 0.052);

- Delta (Δ)SOFA Score: (aOR 1.19; 95% CI 0.96–1.47; p = 0.113).

2.2. Secondary Outcomes

2.2.1. Clinical Cure at End of Therapy

- Absence of Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection (CRBSI): patients with CRBSI had significantly lower odds of achieving clinical cure (aOR 0.04; 95% CI 0.00–0.60; p = 0.020).

- Lower number of invasive devices: an increasing number of devices was associated with lower odds of cure (aOR 0.38; 95% CI 0.15–0.93; p = 0.035).

2.2.2. Microbiological Cure at End of Therapy

- Absence of Sepsis: patients with sepsis had significantly lower odds of microbiological cure (aOR 0.19; 95% CI 0.04–0.90; p = 0.036).

- Targeted therapy: receiving C/A or C/T was associated with higher odds of achieving microbiological cure compared to no targeted therapy (aOR 4.63; 95% CI 0.96–22.18; p = 0.055).

2.3. Exploratory Outcome (30-Day Infection-Related Mortality)

- Septic Shock: (aOR 7.02; 95% CI 1.57–31.36; p = 0.011).

- Targeted therapy: both treatment groups showed significantly lower odds of infection-related mortality compared to no targeted therapy.

- C/A or C/T: (aOR 0.03; 95% CI 0.00–0.30; p = 0.003).

- Other targeted therapies: (aOR 0.08; 95% CI 0.01–0.58; p = 0.013).

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Population

4.2. Data Collection

- Demographics & Comorbidities: Age, sex, ward of hospitalization at onset, and underlying comorbidities (summarized using the Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI]).

- Healthcare Exposures: Prior hospitalization, surgery, antimicrobial therapy, immunosuppressive therapy, or documented P. aeruginosa infection within the preceding 3 months.

- Immunocompromised Status: Defined as active chemotherapy for malignancy, solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplant, absolute neutrophil count < 500 cells/µL, or receipt of immunosuppressive therapy within 90 days prior to infection.

- Clinical Presentation: Sepsis or septic shock status at onset, SOFA score, and the presence of invasive devices (central venous catheter, urinary catheter, mechanical ventilation, chest drainage tube).

- Infection Characteristics: Site of infection (ventilator-associated pneumonia, hospital-acquired pneumonia, bloodstream infection, catheter-related bloodstream infection, complicated urinary tract infection) and polymicrobial status.

- Therapeutic Management: Infectious diseases consultation, source control procedures, empirical therapy (regimens, adequacy, duration), targeted therapy (regimens, timing), and combination therapy use.

4.3. Microbiological Testing

4.4. Definitions and Outcomes

- Primary outcome: 30-day all-cause mortality after infection onset.

- Secondary outcomes: (i) clinical cure at end of therapy and (ii) microbiological cure at end of therapy.

- Exploratory outcome: 30-day infection-related mortality.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maraolo, A.E.; Cascella, M.; Corcione, S.; Cuomo, A.; Nappa, S.; Borgia, G.; De Rosa, F.G.; Gentile, I. Management of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the intensive care unit: State of the art. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2017, 15, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, H.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Hansen, P.; Garlasco, J.; Campagnaro, E.; Boccia, S.; Castillo-Polo, J.A.; Magrini, E.; Garcia-Vello, P.; et al. The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: A prioritisation study to guide research, development, and public health strategies against antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Martín, I.; Sainz-Mejías, M.; McClean, S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An audacious pathogen with an adaptable arsenal of virulence factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidenstein, E.B.M.; de la Fuente-Núñez, C.; Hancock, R.E.W. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: All roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2011, 19, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, S.S.; Adjemian, J.; Lai, Y.L.; Spaulding, A.B.; Ricotta, E.; Prevots, D.R.; Palmore, T.N.; Rhee, C.; Klompas, M.; Dekker, J.P.; et al. Difficult-to-treat resistance in Gram-negative bacteremia at 173 US hospitals: Retrospective cohort analysis of prevalence, predictors, and outcome of resistance to all first-line agents. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 1803–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosentino, F.; Viale, P.; Giannella, M. MDR/XDR/PDR or DTR? Which definition best fits the resistance profile of Pseudomonas aeruginosa? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 36, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.; Komarow, L.; Chen, L.; Ge, L.; Hanson, B.M.; Cober, E.; Herc, E.; Alenazi, T.; Kaye, K.S.; Garcia-Diaz, J.; et al. Global epidemiology and clinical outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and associated carbapenemases (POP): A prospective cohort study. Lancet Microbe. 2023, 4, e159–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macesic, N.; Uhlemann, A.C.; Peleg, A.Y. Multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet 2025, 405, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, M.H.; Fagheei Aghmiyuni, Z.; Bakhti, S. Worldwide threatening prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Epidemiol. Infect. 2025, 153, e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horcajada, J.P.; Gales, A.; Isler, B.; Kaye, K.S.; Kwa, A.L.; Landersdorfer, C.B.; Montero, M.M.; Oliver, A.; Pogue, J.M.; Shields, R.K.; et al. How do I manage difficult-to-treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections? Key questions for today’s clinicians. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraolo, A.E.; Mazzitelli, M.; Trecarichi, E.M.; Buonomo, A.R.; Torti, C.; Gentile, I. Ceftolozane/tazobactam for difficult-to-treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: A systematic review of its efficacy and safety for off-label indications. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Healthcare-associated infections acquired in intensive care units. In Annual Epidemiological Report for 2021; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Falcone, M.; Tiseo, G.; Carbonara, S.; Marino, A.; Di Caprio, G.; Carretta, A. Advancing knowLedge on Antimicrobial Resistant Infections Collaboration Network (ALARICO Network). Mortality Attributable to Bloodstream Infections Caused by Different Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli: Results from a Nationwide Study in Italy (ALARICO Network). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Guo, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Hu, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, Q.; et al. Risk factors and outcomes of inpatients with carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections in China: A 9-year trend and multicenter cohort study. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 18, 1137811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hareza, D.A.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Bonomo, R.A.; Dzintars, K.; Karaba, S.M.; Hawes, A.M.; Tekle, T.; Simner, P.J.; Tamma, P.D. Clinical outcomes and emergence of resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections treated with ceftolozane-tazobactam versus ceftazidime-avibactam. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e0090724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shields, R.K.; Abbo, L.M.; Ackley, R.; Aitken, S.L.; Albrecht, B.; Babiker, A.; PRECEDENT Network. Effectiveness of ceftazidime-avibactam versus ceftolozane-tazobactam for multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in the USA (CACTUS): A multicentre, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almangour, T.A.; Ghonem, L.; Alassiri, D.; Aljurbua, A.; Al Musawa, M.; Alharbi, A.; Alghaith, J.; Damfu, N.; Aljefri, D.; Alfahad, W.; et al. Ceftolozane-Tazobactam Versus Ceftazidime-Avibactam for the Treatment of Infections Caused by Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A Multicenter Cohort Study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e00405-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro, L.; Nicolau, D.P.; De Waele, J.J.; Kuti, J.L.; Larson, K.B.; Gadzicki, E.; Yu, B.; Zeng, Z.; Adedoyin, A.; Rhee, E.G. Lung penetration, bronchopulmonary pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profile and safety of 3 g of ceftolozane/tazobactam administered to ventilated, critically ill patients with pneumonia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 1546–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, D.P.; Siew, L.; Armstrong, J.; Li, J.; Edeki, T.; Learoyd, M.; Das, S. Phase 1 study assessing the steady-state concentration of ceftazidime and avibactam in plasma and epithelial lining fluid following two dosing regimens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2862–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiseo, G.; Brigante, G.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Maraolo, A.E.; Gona, F.; Falcone, M.; Giannella, M.; Grossi, P.; Pea, F.; Rossolini, G.M.; et al. Diagnosis and management of infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria: Guideline endorsed by the Italian Society of Infection and Tropical Diseases (SIMIT), the Italian Society of Anti-Infective Therapy (SITA), the Italian Group for Antimicrobial Stewardship (GISA), the Italian Association of Clinical Microbiologists (AMCLI) and the Italian Society of Microbiology (SIM). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2022, 60, 106611. [Google Scholar]

- Tamma, P.D.; Heil, E.L.; Justo, J.A.; Mathers, A.J.; Satlin, M.J.; Bonomo, R.A. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2024 guidance on the treatment of antimicrobial-resistant gram-negative infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, ciae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, N.; Maraolo, A.E.; Onorato, L.; Scotto, R.; Calò, F.; Atripaldi, L.; Borrelli, A.; Corcione, A.; De Cristofaro, M.G.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; et al. Epidemiology, mechanisms of resistance and treatment algorithm for infections due to carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: An expert panel opinion. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Luo, Y. Efficiency of combination therapy versus monotherapy for the treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ramírez-Estrada, S.; Borgatta, B.; Rello, J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia management. Infect. Drug Resist. 2016, 9, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucrier, A.; Dessalle, T.; Tuffet, S.; Federici, L.; Dahyot-Fizelier, C.; Barbier, F.; Pottecher, J.; Monsel, A.; Hissem, T.; Demoule, A.; et al. Association between combination antibiotic therapy as opposed as monotherapy and outcomes of ICU patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia: An ancillary study of the iDIAPASON trial. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Xie, X. Monotherapy or combination antibiotic therapy in the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Friberg, N.; Mares, M.; Kahlmeter, G.; Meletiadis, J.; Guinea, J. Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AFST) of the ESCMID European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). How to interpret MICs of antifungal compounds according to the revised clinical breakpoints v. 10.0 European committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing (EUCAST). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1464–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Firth, D. Bias Reduction of Maximum Likelihood Estimates. Biometrika 1993, 80, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | Variables | Overall (N = 51) | Alive (N = 26) | Died (N = 25) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit and Demographics | |||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 64.00 (53.00–75.00) | 60.00 (49.37–70.62) | 72.00 (65.00–79.00) | 0.018 | |

| Male sex | 32 (63%) | 17 (65%) | 15 (60%) | 0.7 | |

| ICU Ward of hospitalization at infection onset | 36 (71%) | 16 (62%) | 20 (80%) | 0.15 | |

| Baseline Comorbidity and Other Relevant Factors | |||||

| Myocardial Infarction | 11 (22%) | 6 (23%) | 5 (20%) | 0.8 | |

| Heart failure | 4 (8%) | 3 (12%) | 1 (4%) | 0.6 | |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 8 (16%) | 3 (12%) | 5 (20%) | 0.5 | |

| Stroke | 21 (41%) | 10 (38%) | 11 (44%) | 0.7 | |

| Dementia | 8 (16%) | 4 (15%) | 4 (16%) | >0.9 | |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 27 (53%) | 14 (54%) | 13 (52%) | 0.9 | |

| Connective Tissue Disease | 4 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (12%) | 0.3 | |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease | 8 (16%) | 2 (8%) | 6 (24%) | 0.14 | |

| Chronic liver Disease | 0.2 | ||||

| Mild | 14 (27%) | 5 (19%) | 9 (36%) | ||

| Moderate-to-severe | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | >0.9 | ||||

| Uncomplicated | 7 (14%) | 4 (15%) | 3 (12%) | ||

| End-organ damage | 7 (14%) | 3 (12%) | 4 (16%) | ||

| Hemiplegia or Paraplegia | 13 (25%) | 8 (31%) | 5 (20%) | 0.4 | |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 16 (31%) | 7 (27%) | 9 (36%) | 0.5 | |

| Solid Tumor | 0.5 | ||||

| Localized | 8 (16%) | 3 (12%) | 5 (20%) | ||

| Metastatic | 7 (14%) | 5 (19%) | 2 (8%) | ||

| Leukemia | 4 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (12%) | 0.3 | |

| Lymphoma | 3 (6%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (8%) | 0.6 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 8.00 (5.50–10.5) | 7.50 (4.87–10.12) | 8.00 (6.00–10.00) | 0.4 | |

| Solid Organ Transplant | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0.5 | |

| Severe Neutropenia (<500 cells/µL) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0.5 | |

| Previous Healthcare Exposure | |||||

| Previous hospitalization, last 3 months | 32 (63%) | 16 (62%) | 16 (64%) | 0.9 | |

| Previous Immunosuppressive Drug use, last 3 months | 13 (25%) | 7 (27%) | 6 (24%) | 0.8 | |

| Previous Pseudomonas Infection, last 3 months | 30 (59%) | 18 (69%) | 12 (48%) | 0.12 | |

| Previous antibiotic therapy, last 3 months | 49 (96%) | 24 (92%) | 25 (100%) | 0.5 | |

| Previous surgery, last 3 months | 33 (65%) | 16 (62%) | 17 (68%) | 0.6 | |

| Type of Devices | |||||

| Central Venous Catheter | 46 (90%) | 22 (85%) | 24 (96%) | 0.3 | |

| Foley Urinary Catheter | 46 (90%) | 22 (85%) | 24 (96%) | 0.3 | |

| Mechanical Ventilation | 35 (69%) | 13 (50%) | 22 (88%) | 0.003 | |

| Chest Drainage Tube | 16 (31%) | 5 (19%) | 11 (44%) | 0.057 | |

| Number of Invasive Devices | 0.10 | ||||

| 2 | 5 (9.8%) | 4 (15%) | 1 (4%) | ||

| 3 | 26 (51%) | 13 (50%) | 13 (52%) | ||

| 4 | 12 (24%) | 3 (12%) | 9 (36%) | ||

| 5 | 2 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4.0%) | ||

| Features on Clinical Presentation | |||||

| Sepsis | 41 (80%) | 16 (62%) | 25 (100%) | <0.001 | |

| Septic Shock | 23 (45%) | 4 (15%) | 19 (76%) | <0.001 | |

| Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA Score) | 8.00 (3.75–12.25) | 4.00 (1.00–7.00) | 11.00 (7.50–14.50) | <0.001 | |

| Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA Score), Delta | 5.00 (1.00–9.00) | 2.00 (0.00–4.00) | 9.00 (7.50–10.50) | <0.001 | |

| Polymicrobial Infection | 44 (86%) | 21 (81%) | 23 (92%) | 0.4 | |

| Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP) | 10 (20%) | 6 (23%) | 4 (16%) | 0.7 | |

| Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP) | 33 (65%) | 13 (50%) | 20 (80%) | 0.025 | |

| Complicated Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) | 3 (6%) | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 0.2 | |

| Bloodstream Infection (BSI) | 15 (29%) | 7 (27%) | 8 (32%) | 0.7 | |

| Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection (CRBSI) | 7 (14%) | 3 (12%) | 4 (16%) | 0.7 | |

| Treatment-Related Variables | |||||

| Infectious Diseases Consultation | 46 (90%) | 24 (92%) | 22 (88%) | 0.7 | |

| Source Control | 0.6 | ||||

| Needed but not performed | 2 (3.9%) | 2 (7.7%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Needed and performed | 8 (16%) | 4 (15%) | 4 (16%) | ||

| Empirical Therapy | Empirical therapy | 41 (80%) | 19 (73%) | 22 (88%) | 0.3 |

| Empirical monotherapy | 25 (49%) | 11 (42%) | 14 (56%) | 0.4 | |

| Adequate empirical therapy | 8 (16%) | 4 (15%) | 4 (16%) | 0.5 | |

| Duration of Empirical therapy, days (n = 41) | 10.00 (5.50–14.50) | 14.00 (9.50–18.50) | 8.50 (5.13–11.87) | 0.011 | |

| Targeted Backbone Therapy | 0.029 | ||||

| Amikacin | 2 (4%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Cefiderocol | 8 (16%) | 5 (19%) | 3 (12%) | ||

| Ceftazidime/Avibactam | 9 (18%) | 3 (12%) | 6 (24%) | ||

| Ceftolozane/Tazobactam | 12 (24%) | 10 (38%) | 2 (8%) | ||

| Colistin | 6 (12%) | 2 (8%) | 4 (16%) | ||

| Targeted monotherapy | 18 (35%) | 13 (50%) | 5 (20%) | 0.046 | |

| Days to Active Therapy, days (n = 37) | 6.00 (2.00–10.00) | 8.00 (4.25–11.75) | 4.00 (1.25–6.75) | 0.010 |

| 30-Day All-Cause Mortality (Alive = 26, Died = 25) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Univariable OR (CI 95%, p-Value) | Multivariable aOR (CI 95%, p-Value) | Final Model aOR (CI 95%, p-Value) | Final Model with Firth aOR (CI 95%, p-Value) | |

| Age | 1.05 (1.01–1.09, p = 0.020) | 1.06 (0.99–1.14, p = 0.096) | 1.07 (1.01–1.17, p = 0.049) | 1.06 (1.00–1.12, p = 0.052) | |

| Ward of hospitalization at infection onset | ICU | 2.50 (0.71–8.80, p = 0.154) | 0.36 (0.01–14.22, p = 0.589) | ||

| Sex | Male | 0.79 (0.25–2.48, p = 0.691) | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.11 (0.94–1.31, p = 0.223) | ||||

| Previous hospitalization, last 3 months | Yes | 1.11 (0.36–3.46, p = 0.856) | |||

| Previous antibiotic therapy, last 3 months | Yes | 6,303,500.55 (0.00–Inf, p = 0.992) | |||

| Immunodeficiency | Yes | 0.92 (0.31–2.77, p = 0.886) | |||

| Previous Pseudomonas Infection, last 3 months | Yes | 0.41 (0.13–1.29, p = 0.127) | 0.31 (0.02–4.28, p = 0.381) | ||

| Previous surgery, last 3 months | Yes | 1.33 (0.42–4.21, p = 0.630) | |||

| Mechanical Ventilation | Yes | 7.33 (1.75–30.66, p = 0.006) | 7.05 (0.00–220,315.49, p = 0.712) | ||

| Foley Urinary Catheter | Yes | 4.36 (0.45–42.08, p = 0.203) | |||

| Central Venous Catheter | Yes | 4.36 (0.45–42.08, p = 0.203) | |||

| Chest Drainage Tube | Yes | 3.30 (0.94–11.57, p = 0.062) | 1.77 (0.11–29.38, p = 0.692) | ||

| Septic Shock | Yes | 17.42 (4.27–71.07, p < 0.001) | 8.44 (0.80–89.03, p = 0.076 | 8.04 (1.25–68.1, p = 0.035) | 5.52 (1.04–29.27, p = 0.045) |

| Nosocomial Pneumonia (reference: no pneumonia) | HAP | 4.67 (0.40–53.95, p = 0.217) | 5.23 (0.09–319.12, p = 0.430) | ||

| VAP | 10.77 (1.18–98.03, p = 0.035) | 1.84 (0.00–70,055.10, p = 0.909) | |||

| Bloodstream Infection (BSI) or Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection (CRBSI) (reference no BSI/CRBSI) | BSI | 1.90 (0.45–7.98, p = 0.381) | |||

| CRBSI | 1.69 (0.33–8.73, p = 0.532) | ||||

| Infectious Diseases Consultation | Yes | 0.61 (0.09–4.01, p = 0.608) | |||

| Empirical therapy (reference: No empirical therapy) | Not adequate | 2.80 (0.61–12.75, p = 0.183) | 2.50 (0.13–47.58, p = 0.541) | ||

| Adequate | 2.33 (0.34–16.18, p = 0.391) | 1.40 (0.04–47.42, p = 0.853) | |||

| Targeted therapy: Ceftazidime/Avibactam or Ceftolozane/Tazobactam vs. Other | C/A or C/T | 0.25 (0.06–1.06, p = 0.059) | 0.10 (0.00–2.97, p = 0.185) | 0.10 (0.01–0.96, p = 0.067) | 0.15 (0.02–1.17, p = 0.070) |

| (reference: no targeted treatment) | Other | 0.31 (0.07–1.43, p = 0.133) | 0.10 (0.00–4.69, p = 0.237) | 0.08 (0.00–0.77, p = 0.046) | 0.13 (0.02–1.02, p = 0.052) |

| Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score, Delta | 1.45 (1.19–1.77, p < 0.001) | 1.20 (0.89–1.64, p = 0.236) | 1.23 (0.97–1.61, p = 0.10) | 1.19 (0.96–1.47, p = 0.113) | |

| Polymicrobial Infection | Yes | 2.74 (0.48–15.65, p = 0.257) | |||

| Clinical Cure at End of Therapy (No Clinical Cure = 34, Clinical Cure = 17) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Univariable OR (CI 95%, p-Value) | Multivariable aOR (CI 95%, p-Value) | Final Model aOR (CI 95%, p-Value) | Final Model with Firth aOR (CI 95%, p-Value) | |

| Age | 0.96 (0.92–1.00, p = 0.041) | 0.93 (0.86–1.01, p = 0.087) | 0.94 (0.88–1.00, p = 0.053) | 0.96 (0.91–1.00, p = 0.062) | |

| Ward of hospitalization at infection onset | ICU | 0.19 (0.05–0.70, p = 0.012) | 0.13 (0.01–3.18, p = 0.212) | 0.11 (0.01–0.95, p = 0.045) | 0.22 (0.04–1.24, p = 0.085) |

| Sex | Male | 0.78 (0.24–2.57, p = 0.682) | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.89 (0.74–1.07, p = 0.208) | ||||

| Previous hospitalization, last 3 months | Yes | 2.57 (0.69–9.50, p = 0.158) | 3.04 (0.19–49.51, p = 0.434) | ||

| Immunodeficiency | Yes | 1.81 (0.56–5.89, p = 0.324) | |||

| Previous antibiotic therapy, last 3 months | Yes | 0.00 (0.00–Inf, p = 0.992) | |||

| Previous Pseudomonas Infection, last 3 months | Yes | 1.00 (0.31–3.26, p = 1.000) | |||

| Previous surgery, last 3 months | Yes | 0.32 (0.09–1.08, p = 0.067) | 0.22 (0.01–3.70, p = 0.291) | ||

| Number of Invasive Devices | 0.27 (0.11–0.63, p = 0.003) | 1.12 (0.11–11.26, p = 0.921) | 0.26 (0.06–0.78, p = 0.034) | 0.38 (0.15–0.93, p = 0.035) | |

| Sepsis | Yes | 0.07 (0.01–0.39, p = 0.002) | 0.09 (0.00–5.24, p = 0.247) | 0.08 (0.00–0.80, p = 0.056) | 0.18 (0.03–1.21, p = 0.077) |

| Nosocomial Pneumonia (reference: no pneumonia) | HAP | 0.90 (0.13–6.08, p = 0.914) | 0.00 (0.00-Inf, p = 0.997) | ||

| VAP | 0.13 (0.02–0.72, p = 0.019) | 0.00 (0.00–Inf, p = 0.997) | |||

| Bloodstream Infection (BSI) or Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection (CRBSI) (reference no BSI/CRBSI) | BSI | 0.14 (0.02–1.24, p = 0.077) | 0.00 (0.00–Inf, p = 0.996) | 0.01 (0.00–0.45, p = 0.086) | 0.05 (0.00–1.02, p = 0.052) |

| CRBSI | 0.21 (0.02–1.95, p = 0.170) | 0.00 (0.00–Inf, p = 0.996) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.22, p = 0.020) | 0.04 (0.00–0.60, p = 0.020) | |

| Infectious Diseases Consultation | Yes | 0.73 (0.11–4.82, p = 0.740) | |||

| Empirical therapy (reference: No empirical therapy) | No | 1.17 (0.25–5.41, p = 0.844) | |||

| Yes | 1.40 (0.20–10.03, p = 0.738) | ||||

| Targeted therapy: Ceftazidime/Avibactam or Ceftolozane/Tazobactam vs. Other | C/A or C/T | 1.87 (0.44–7.96, p = 0.394) | |||

| (reference: no targeted treatment) | Other | 0.83 (0.16–4.21, p = 0.825) | |||

| Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score, Delta | 0.67 (0.53–0.85, p = 0.001) | 0.93 (0.62–1.39, p = 0.712) | |||

| Polymicrobial Infection | Yes | 0.31 (0.06–1.61, p = 0.165) | 0.00 (0.00-Inf, p = 0.997) | ||

| Microbiological Cure at End of Therapy (No Microbiological Cure = 28, Microbiological Cure = 23) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Univariable OR (CI 95%, p-Value) | Multivariable aOR (CI 95%, p-Value) | Final Model aOR (CI 95%, p-Value) | Final Model with Firth aOR (CI 95%, p-Value) | |

| Age | 0.99 (0.96–1.03, p = 0.676) | ||||

| Ward of hospitalization at infection onset | ICU | 0.42 (0.12–1.45, p = 0.172) | 10.37 (0.45–237.58, p = 0.143) | ||

| Sex | Male | 0.44 (0.14–1.39, p = 0.161) | 0.19 (0.02–1.44, p = 0.108) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.13 (0.95–1.34, p = 0.165) | 1.08 (0.78–1.50, p = 0.630) | |||

| Previous hospitalization, last 3 months | Yes | 3.60 (1.04–12.40, p = 0.042) | 3.23 (0.49–21.42, p = 0.225) | 3.65 (0.90–17.5, p = 0.080) | 3.14 (0.84–11.72, p = 0.088) |

| Immunodeficiency | Yes | 1.73 (0.57–5.28, p = 0.333) | |||

| Previous antibiotic therapy, last 3 months | Yes | 0.00 (0.00–Inf, p = 0.992) | |||

| Previous Pseudomonas Infection, last 3 months | Yes | 1.17 (0.38–3.59, p = 0.788) | |||

| Previous surgery, last 3 months | Yes | 0.52 (0.16–1.66, p = 0.270) | |||

| Number of Invasive Devices | 0.62 (0.34–1.13, p = 0.121) | 1.29 (0.25–6.68, p = 0.758) | |||

| Sepsis | Yes | 0.14 (0.03–0.77, p = 0.023) | 0.10 (0.00–2.30, p = 0.148) | 0.14 (0.02–0.71, p = 0.030) | 0.19 (0.04–0.90, p = 0.036) |

| Nosocomial Pneumonia (reference: no pneumonia) | HAP | 1.40 (0.20–10.03, p = 0.738) | 3.26 (0.10–107.22, p = 0.508) | ||

| VAP | 0.30 (0.06–1.49, p = 0.141) | 0.27 (0.00–37.67, p = 0.604) | |||

| Bloodstream Infection (BSI) or Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection (CRBSI) (reference no BSI/CRBSI) | BSI | 0.22 (0.04–1.20, p = 0.081) | 0.89 (0.08–10.18, p = 0.923) | ||

| CRBSI | 0.67 (0.13–3.44, p = 0.628) | 0.09 (0.01–1.59, p = 0.102) | |||

| Infectious Diseases Consultation | Yes | 3.67 (0.38–35.36, p = 0.261) | |||

| Empirical therapy (reference: No empirical therapy) | No | 2.20 (0.48–9.99, p = 0.309) | |||

| Yes | 2.33 (0.34–16.18, p = 0.391) | ||||

| Targeted therapy: Ceftazidime/Avibactam or Ceftolozane/Tazobactam vs. Other (reference: no targeted treatment) | C/A or C/T | 5.96 (1.26–28.10, p = 0.024) | 8.60 (0.82–89.85, p = 0.072) | 5.70 (1.10–39.0, p = 0.050) | 4.63 (0.96–22.18, p = 0.055) |

| Other | 2.85 (0.57–14.33, p = 0.203) | 3.48 (0.23–51.56, p = 0.365) | 3.81 (0.64–30.1, p = 0.200) | 3.16 (0.59–16.97, p = 0.179) | |

| Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score, Delta | 0.83 (0.71–0.96, p = 0.013) | 0.89 (0.65–1.21, p = 0.452) | |||

| Polymicrobial Infection | Yes | 0.57 (0.11–2.86, p = 0.494) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maraolo, A.E.; Gallicchio, A.; Fotticchia, V.; Catania, M.R.; Scotto, R.; Gentile, I. Clinical Outcomes and Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Difficult-to-Treat Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010033

Maraolo AE, Gallicchio A, Fotticchia V, Catania MR, Scotto R, Gentile I. Clinical Outcomes and Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Difficult-to-Treat Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaraolo, Alberto Enrico, Antonella Gallicchio, Vincenzo Fotticchia, Maria Rosaria Catania, Riccardo Scotto, and Ivan Gentile. 2026. "Clinical Outcomes and Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Difficult-to-Treat Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010033

APA StyleMaraolo, A. E., Gallicchio, A., Fotticchia, V., Catania, M. R., Scotto, R., & Gentile, I. (2026). Clinical Outcomes and Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Difficult-to-Treat Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Antibiotics, 15(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010033