Comparative Phenotypic and Genotypic Analysis of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains Isolated from Poultry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

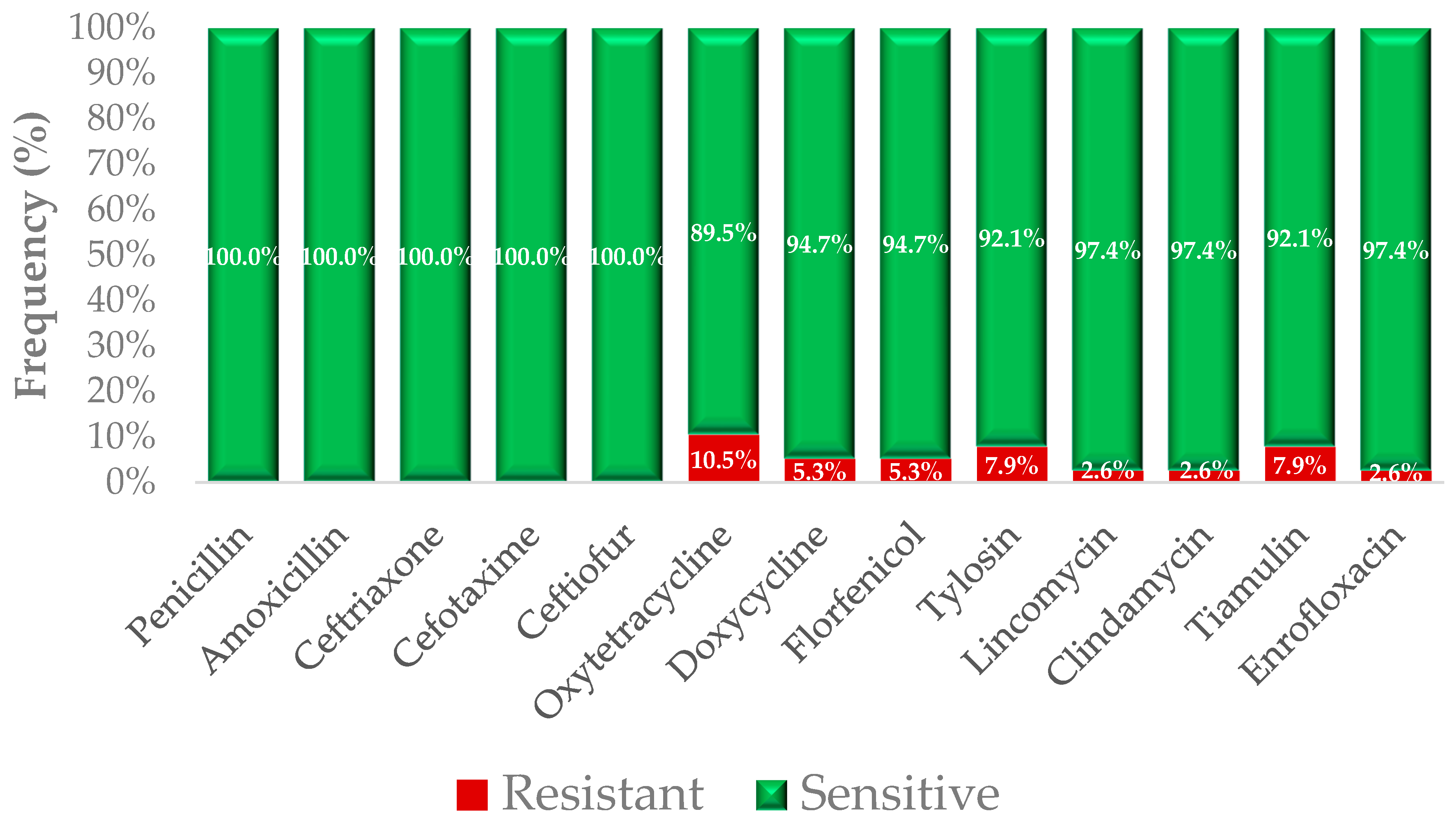

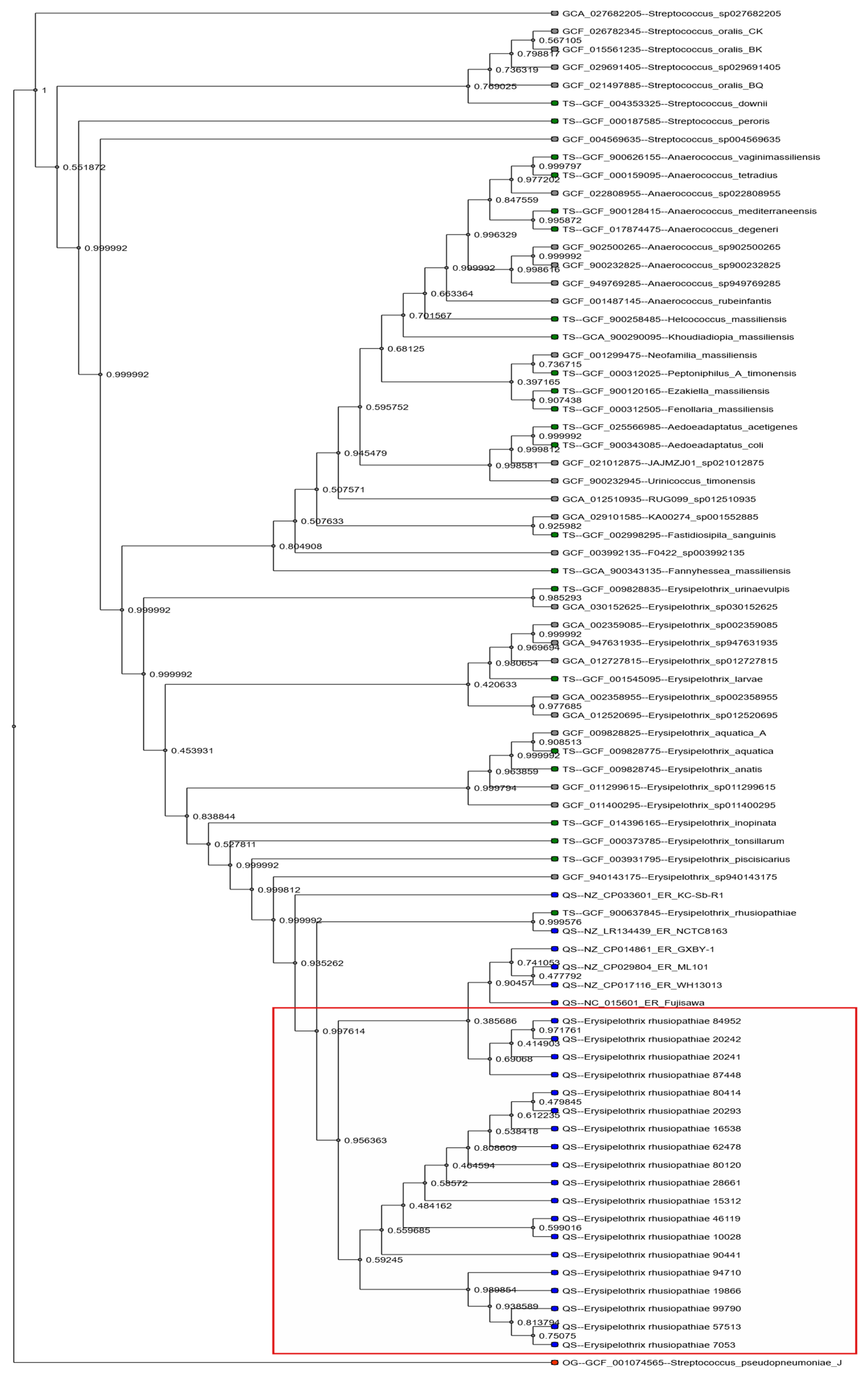

2.1. Phenotypic Resistance Profiles

2.2. Correlation Between Phenotypic Resistance and Resistance Gene Carriage

2.3. Genomic Resistance Determinants

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling and Identification of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains

4.2. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

4.3. Next-Generation Sequencing

4.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nhung, N.T.; Chansiripornchai, N.; Carrique-Mas, J.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacterial Poultry Pathogens: A Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Brower, C.; Gilbert, M.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Robinson, T.P.; Teillant, A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global Trends in Antimicrobial Use in Food Animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5649–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnácz, F.; Kerek, Á.; Csirmaz, B.; Román, I.L.; Gál, C.; Horváth, Á.; Hajduk, E.; Szabó, Á.; Jerzsele, Á.; Kovács, L. The Status of Antimicrobial Resistance in Domestic Poultry with Different Breeding Purposes in Hungary Between 2022–2023. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2024, 146, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebők, C.; Márton, R.A.; Meckei, M.; Neogrády, Z.; Mátis, G. Antimicrobial Peptides as New Tools to Combat Infectious Diseases. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2024, 146, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, L.; Nagy, D.; Könyves, L.; Jerzsele, Á.; Kerek, Á. Antimicrobial Properties of Essential Oils—Animal Health Aspects. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2023, 145, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerzsele, Á.; Somogyi, Z.; Szalai, M.; Kovács, D. Effects of Fermented Wheat Germ Extract on Artificial Salmonella Typhimurium Infection in Broiler Chickens. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2020, 142, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Olasz, Á.; Jerzsele, Á.; Balta, L.; Dobra, P.F.; Kerek, Á. In Vivo Efficacy of Different Extracts of Propolis in Broiler Salmonellosis. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2023, 145, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerek, Á.; Csanády, P.; Jerzsele, Á. Antibacterial Efficiency of Propolis—Part 1. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2022, 144, 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Kerek, Á.; Csanády, P.; Jerzsele, Á. Antiprotozoal and Antifungal Efficiency of Propolis—Part 2. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2022, 144, 691–704. [Google Scholar]

- Such, N.; Molnár, A.; Pál, L.; Farkas, V.; Menyhárt, L.; Husvéth, F.; Dublecz, K. The Effect of Pre- and Probiotic Treatment on the Gumboro-Titer Values of Broilers. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2021, 143, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, L.; Hejel, P.; Farkas, M.; László, L.; Könyves, L. Study Report on the Effect of a Litter Treatment Product Containing Bacillus licheniformis and Zeolite in Male Fattening Turkey Flock. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2024, 146, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetényi, N.; Bersényi, A.; Hullár, I. Physiological Effects of Medium-Chain Fatty Acids and Triglycerides, and Their Potential Use in Poultry and Swine Nutrition: A Literature Review. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2024, 146, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jócsák, G.; Schilling-Tóth, B.; Bartha, T.; Tóth, I.; Ondrašovičová, S.; Kiss, D.S. Metal Nanoparticles—Immersion in the „tiny” World of Medicine. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2025, 147, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, M.; Könyves, L.; Csorba, S.; Farkas, Z.; Józwiák, Á.; Süth, M.; Kovács, L. Biosecurity Situation of Large-Scale Poultry Farms in Hungary According to the Databases of National Food Chain Safety Office Centre for Disease Control and Biosecurity Audit System of Poultry Product Board of Hungary in the Period of 2021–2022. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2024, 146, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, L.; Klaucke, C.R.; Farkas, M.; Bakony, M.; Jurkovich, V.; Könyves, L. The Correlation between On-Farm Biosecurity and Animal Welfare Indices in Large-Scale Turkey Production. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mag, P.; Németh, K.; Somogyi, Z.; Jerzsele, Á. Antibacterial therapy based on pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models in small animal medicine-1. Literature review. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2023, 145, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, D.A.; Zhao, S.; Tong, E.; Ayers, S.; Singh, A.; Bartholomew, M.J.; McDermott, P.F. Antimicrobial Drug Resistance in Escherichia coli from Humans and Food Animals, United States, 1950–2002. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2012, 18, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolaia, V.; Espinosa-Gongora, C.; Guardabassi, L. Human Health Risks Associated with Antimicrobial-Resistant Enterococci and Staphylococcus aureus on Poultry Meat. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S.M.; Kottwitz, J.; Keller, D.I.; Albini, S. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Infection by Geese to Human Transmission. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e240073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, C.J.; Riley, T.V. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: Bacteriology, Epidemiology and Clinical Manifestations of an Occupational Pathogen. J. Med. Microbiol. 1999, 48, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straw, B.E.; Zimmerman, J.J.; D’Allaire, S.; Taylor, D.J. Diseases of Swine; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-70490-5. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, E.H.; Berman, D.T. Isolation of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae from Tonsils of Apparently Normal Swine by Two Methods. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1978, 39, 187–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veraldi, S.; Girgenti, V.; Dassoni, F.; Gianotti, R. Erysipeloid: A Review. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 34, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reboli, A.C.; Farrar, W.E. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: An Occupational Pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1989, 2, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobrek, K.; Nowak, M.; Borkowska, J.; Bobusia, K.; Gaweł, A. An Outbreak of Erysipelas in Commercial Geese. Pak. Vet. J. 2016, 36, 372–374. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann-Bart, M.; Hoop, R.K. Diseases in Chicks and Laying Hens during the First 12 Years after Battery Cages Were Banned in Switzerland. Vet. Rec. 2009, 164, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgaard, M.; Olsen, P. Erysipelas in Egg-Laying Chickens: Clinical, Pathological and Bacteriological Investigations. Avian Pathol. 1975, 4, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri, A.; Lierz, M.; Hafez, H.M. Investigations on the Pathogenicity of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae in Laying Hens. Avian Dis. 2005, 49, 574–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, H.; Brännström, S.; Skarin, H.; Chirico, J. Characterization of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Isolates from Laying Hens and Poultry Red Mites (Dermanyssus gallinae) from an Outbreak of Erysipelas. Avian Pathol. 2010, 39, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, H.; Bagge, E.; Båverud, V.; Fellström, C.; Jansson, D.S. Erysipelothrix Rhusiopathiae Contamination in the Poultry House Environment during Erysipelas Outbreaks in Organic Laying Hen Flocks. Avian Pathol. 2014, 43, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, H.; Hayashidani, H.; Higashi, J.; Kaneko, K.; Takahashi, T.; Ogawa, M. Occurrence of Erysipelothrix spp. in Broiler Chickens at an Abattoir. J. Food Prot. 1998, 61, 907–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, H.; Jansson, D.S.; Johansson, K.-E.; Båverud, V.; Chirico, J.; Aspán, A. Characterization of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Isolates from Poultry, Pigs, Emus, the Poultry Red Mite and Other Animals. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 137, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrek, K.; Gaweł, A. Antimicrobial Resistance of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains Isolated from Geese to Antimicrobials Widely Used in Veterinary Medicine. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dec, M.; Łagowski, D.; Nowak, T.; Pietras-Ożga, D.; Herman, K. Serotypes, Antibiotic Susceptibility, Genotypic Virulence Profiles and SpaA Variants of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains Isolated from Pigs in Poland. Pathogens 2023, 12, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Lv, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Kang, C.; Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Characterization of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Isolates from Diseased Pigs in 15 Chinese Provinces from 2012 to 2018. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Li, Y.-X.; Xu, C.-W.; Xie, X.-J.; Li, P.; Ma, G.-X.; Lei, C.-W.; Liu, J.-X.; Zhang, A.-Y. Genome Sequence of Multidrug-Resistant Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae ZJ Carrying Several Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance Genes. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 21, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, M.; Gelfusa, V.; Tarasi, A.; Brandimarte, C.; Serra, P. Antimicrobial Susceptibilities of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1990, 34, 2038–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Sawada, T.; Ohmae, K.; Terakado, N.; Muramatsu, M.; Seto, K.; Maruyama, T.; Kanzaki, M. Antibiotic Resistance of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Isolated from Pigs with Chronic Swine Erysipelas. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1984, 25, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, R.; Formenti, N.; Caló, S.; Chiari, M.; Zoric, M.; Alborali, G.L.; Sørensen Dalgaard, T.; Wattrang, E.; Eriksson, H. Comparative Genome Analysis of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Isolated from Domestic Pigs and Wild Boars Suggests Host Adaptation and Selective Pressure from the Use of Antibiotics. Microb. Genom. 2020, 6, e000412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.C. Update on Acquired Tetracycline Resistance Genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 245, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, C.; Varaldo, P.E.; Facinelli, B. Streptococcus suis, an Emerging Drug-Resistant Animal and Human Pathogen. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Ooka, T.; Shi, F.; Ogura, Y.; Nakayama, K.; Hayashi, T.; Shimoji, Y. The Genome of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, the Causative Agent of Swine Erysipelas, Reveals New Insights into the Evolution of Firmicutes and the Organism’s Intracellular Adaptations. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 2959–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Schwarz, S.; Li, X.-S.; Shang, Y.-H.; Du, X.-D. Emergence of a Tet(M) Variant Conferring Resistance to Tigecycline in Streptococcus suis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 709327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI Standards M07; Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 11th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018.

- CLSI Standards VET06; Methods for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria Isolated From Animals, 1st ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017.

- VET01SEd5; Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated From Animals, 5th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024.

- Muzzey, D.; Evans, E.A.; Lieber, C. Understanding the Basics of NGS: From Mechanism to Variant Calling. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 2015, 3, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihály, Z.; Győrffy, B. Next generation sequencing technologies (NGST) development and applications. Orvosi Hetil. 2011, 152, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC—A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, G.; Lavenier, D.; Lemaitre, C.; Rizk, G. Bloocoo, a Memory Efficient Read Corrector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computational Biology (ECCB), Strasbourg, France, 7–10 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.-M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: An Ultra-Fast Single-Node Solution for Large and Complex Metagenomics Assembly via Succinct de Bruijn Graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilinetc, I.; Prjibelski, A.D.; Gurevich, A.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P.A. Assembling Short Reads from Jumping Libraries with Large Insert Sizes. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3262–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicedomini, R.; Vezzi, F.; Scalabrin, S.; Arvestad, L.; Policriti, A. GAM-NGS: Genomic Assemblies Merger for next Generation Sequencing. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Simao, F.A.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 4647–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurture, G.W.; Sedlazeck, F.J.; Nattestad, M.; Underwood, C.J.; Fang, H.; Gurtowski, J.; Schatz, M.C. GenomeScope: Fast Reference-Free Genome Profiling from Short Reads. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2202–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldgarden, M.; Brover, V.; Haft, D.H.; Prasad, A.B.; Slotta, D.J.; Tolstoy, I.; Tyson, G.H.; Zhao, S.; Hsu, C.-H.; McDermott, P.F.; et al. Validating the AMRFinder Tool and Resistance Gene Database by Using Antimicrobial Resistance Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in a Collection of Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00483-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Raphenya, A.R.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Tsang, K.K.; Bouchard, M.; Edalatmand, A.; Huynh, W.; Nguyen, A.-L.V.; Cheng, A.A.; Liu, S.; et al. CARD 2020: Antibiotic Resistome Surveillance with the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D517–D525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Zheng, D.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. VFDB 2022: A General Classification Scheme for Bacterial Virulence Factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D912–D917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, M.H.K.; Bortolaia, V.; Tansirichaiya, S.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Roberts, A.P.; Petersen, T.N. Detection of Mobile Genetic Elements Associated with Antibiotic Resistance in Salmonella enterica Using a Newly Developed Web Tool: MobileElementFinder. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krawczyk, P.S.; Lipinski, L.; Dziembowski, A. PlasFlow: Predicting Plasmid Sequences in Metagenomic Data Using Genome Signatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the Quality of Microbial Genomes Recovered from Isolates, Single Cells, and Metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Salzberg, S.L. Kraken: Ultrafast Metagenomic Sequence Classification Using Exact Alignments. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, C.; Laird, M.R.; Williams, K.P.; Simon Fraser University Research Computing Group; Lau, B.Y.; Hoad, G.; Winsor, G.L.; Brinkman, F.S. IslandViewer 4: Expanded Prediction of Genomic Islands for Larger-Scale Datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W30–W35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, S.; Larsen, M.V.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Lund, O. PathogenFinder—Distinguishing Friend from Foe Using Bacterial Whole Genome Sequence Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibiotics | Breakpoint | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | MIC50 | MIC90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (µg/mL) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Penicillin | 0.25 | 25 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.001 | 0.031 | ||||||||||||||

| 65.8% | 7.9% | 2.6% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 10.5% | 10.5% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Amoxicillin | 0.5 | 2 | 5 | 15 | 9 | 7 | 0.031 | 0.125 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5.3% | 13.2% | 39.5% | 23.7% | 18.4% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ceftiofur | 8 | 1 | 35 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2.6% | 92.1% | 2.6% | 2.6% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ceftriaxone | 2 | 12 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.004 | 0.063 | ||||||||||

| 31.6% | 2.6% | 18.4% | 13.2% | 13.2% | 2.6% | 7.9% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 5.3% | ||||||||||||||

| Cefotaxime | 2 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.25 | ||||||||||

| 57.9% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 15.8% | 5.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.3% | 2.6% | 7.9% | ||||||||||||||

| Oxytetracycline | 16 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 | ||||||||||||

| 2.6% | 21.1% | 26.3% | 21.1% | 18.4% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.6% | ||||||||||||||||

| Doxycycline | 16 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |||||||||||

| 2.6% | 5.3% | 2.6% | 5.3% | 31.6% | 28.9% | 13.2% | 5.3% | 2.6% | 2.6% | |||||||||||||||

| Florfenicol | 32 | 2 | 17 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 16 | ||||||||||||

| 5.3% | 44.7% | 7.9% | 28.9% | 7.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 2.6% | ||||||||||||||||

| Lincomycin | 16 | 1 | 30 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| 2.6% | 78.9% | 13.2% | 2.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tylosin | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 18 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.008 | 0.25 | |||||||||

| 2.6% | 10.5% | 2.6% | 47.4% | 2.6% | 5.3% | 2.6% | 5.3% | 13.2% | 0.0% | 5.3% | 2.6% | |||||||||||||

| Tiamulin | 32 | 1 | 22 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 2.6% | 57.9% | 26.3% | 5.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 5.3% | |||||||||||||||||

| Clindamycin | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0.015 | 0.25 | ||||||||||

| 2.6% | 13.2% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 36.8% | 7.9% | 10.5% | 7.9% | 7.9% | 7.9% | 2.6% | ||||||||||||||

| Enrofloxacin | 1 | 16 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.002 | 0.125 | |||||||||

| 42.1% | 21.1% | 0.0% | 7.9% | 0.0% | 5.3% | 2.6% | 13.2% | 5.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.6% | |||||||||||||

| Antibiotics | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | MIC50 | MIC90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (µg/mL) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Imipenem | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 7 | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 2.6% | 0.0% | 5.3% | 7.9% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 60.5% | 18.4% | ||||||||||||||

| Linezolid | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 18 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 26.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 23.7% | 47.4% | 2.6% | |||||||||||||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 24 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.001 | 0.063 | |||||||||||

| 63.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 21.1% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 5.3% | ||||||||||||||

| Potentiated sulphonamide 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 0.031 | 0.5 | ||||||||||

| 2.6% | 2.6% | 15.8% | 15.8% | 5.3% | 18.4% | 7.9% | 5.3% | 7.9% | 13.2% | 5.3% | |||||||||||||

| Vancomycin | 27 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 64 | 256 | ||||||||||||||||

| 71.1% | 0.0% | 21.1% | 0.0% | 7.9% | |||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kerek, Á.; Tornyos, G.; Kaszab, E.; Fehér, E.; Jerzsele, Á. Comparative Phenotypic and Genotypic Analysis of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains Isolated from Poultry. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010011

Kerek Á, Tornyos G, Kaszab E, Fehér E, Jerzsele Á. Comparative Phenotypic and Genotypic Analysis of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains Isolated from Poultry. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleKerek, Ádám, Gergely Tornyos, Eszter Kaszab, Enikő Fehér, and Ákos Jerzsele. 2026. "Comparative Phenotypic and Genotypic Analysis of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains Isolated from Poultry" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010011

APA StyleKerek, Á., Tornyos, G., Kaszab, E., Fehér, E., & Jerzsele, Á. (2026). Comparative Phenotypic and Genotypic Analysis of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Strains Isolated from Poultry. Antibiotics, 15(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010011